Abstract

Purpose

Here we aimed to identify a novel genetic cause of tooth agenesis (TA) and/or orofacial clefting (OFC) by combining whole exome sequencing (WES) and targeted re-sequencing in a large cohort of TA and OFC patients.

Methods

WES was performed in two unrelated patients, one with severe TA and OFC and another with severe TA only. After identifying deleterious mutations in a gene encoding the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 (LRP6), all its exons were re-sequenced with molecular inversion probes, in 67 patients with TA, 1,072 patients with OFC and in 706 controls.

Results

We identified a frameshift (c.4594delG, p.Cys1532fs) and a canonical splice site mutation (c.3398-2A>C, p.?) in LRP6 respectively in the patient with TA and OFC, and in the patient with severe TA only. The targeted re-sequencing showed significant enrichment of unique LRP6 variants in TA patients, but not in nonsyndromic OFC. From the 5 variants in patients with TA, 2 affect the canonical splice site and 3 were missense variants; all variants segregated with the dominant phenotype and in 1 case the missense mutation occurred de novo.

Conclusion

Mutations in LRP6 cause tooth agenesis in man.

Keywords: LRP6, Wnt/β-catenin canonical signaling pathway, tooth agenesis, molecular inversion probes

INTRODUCTION

Tooth agenesis (TA) and orofacial clefting (OFC) are distressing to families. Both are common congenital disorders, and can occur as isolated entities; associated with other symptoms; or as part of a syndrome1,2. As isolated condition the severe form of TA with 6 or more teeth failing to develop (oligodontia), has a prevalence of 0.1- 0.5% in populations worldwide, while the frequency of the mild form of TA with 1 to 5 teeth missing (hypodontia), affects 3-20% of the population.2 For isolated nonsyndromic OFC, a worldwide prevalence of 0.1-0.2% is reported.1

While genetic heterogeneity is present for selective tooth agenesis (STHAG) including causal mutations in e.g. MSX1 [STHAG1; MIM:#106600]3, PAX9 [STHAG3; MIM:#604625], WNT10A [STHAG4; MIM: #150400] or EDA [STHAGX1; MIM:#313500], mutations of WNT10A, ligand of the Frizzled (FZD) co-receptor in the canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway, are most frequently associated with isolated tooth agenesis4. From all genes in which mutations causing STHAG have been identified, only MSX1 has the annotation ‘with or without orofacial cleft’, referring to the rare combination of TA and different types of OFC in the affected members in two families identified to date.5,6

Mutations in other genes like IRF6 [MIM: 607199] and TP63 [MIM:603273] have also been shown to cause combined TA-OFC, in syndromic as well as non-syndromic phenotypes.7

Although individuals with OFC present with higher frequencies of dental anomalies including TA in their maxillary primary and permanent dentitions than controls, it was suggested that the combined TA-OFC phenotype is only rarely due to genetic factors, but rather due to acquired disturbances of the physical environment surrounding the developing dentition. Only some families carry rare mutations in specific genes that influence both tooth development and palatogenesis, suggesting rare monogenic conditions in such cases.8

Here we report the discovery of truncating mutations in LRP6 [MIM:*603507] by whole exome sequencing (WES), in a case with TA-OFC and with TA only and we hypothesize that LRP6 mutations can cause TA, OFC, or combined TA-OFC. Through targeted re-sequencing we identified 5 additional patients with TA harbouring LRP6 mutations. To support our hypothesis, we analyzed the expression of Lrp6 in frontal sections of developing mouse heads at embryonic days 13 and 15 (E13 and E15) using immunohistochemistry. As mutations in TP63 have been shown to underlie the combined TA-OFC phenotype, we investigated whether Trp63 and Lrp6 function in the same molecular pathway.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Patients phenotype description

The first index patient was a male born with a bilateral cleft lip, a left-sided cleft of the alveolus, and a complete cleft of the hard and soft palate. He had agenesis of 4 deciduous and 17 permanent teeth. Additional features were growth retardation, hypermetropia, and a small median alveolar cleft in the mandible (Figure 1. A-H). His mother also suffered from severe TA, but not OFC, as well as the maternal grandmother and her brother.

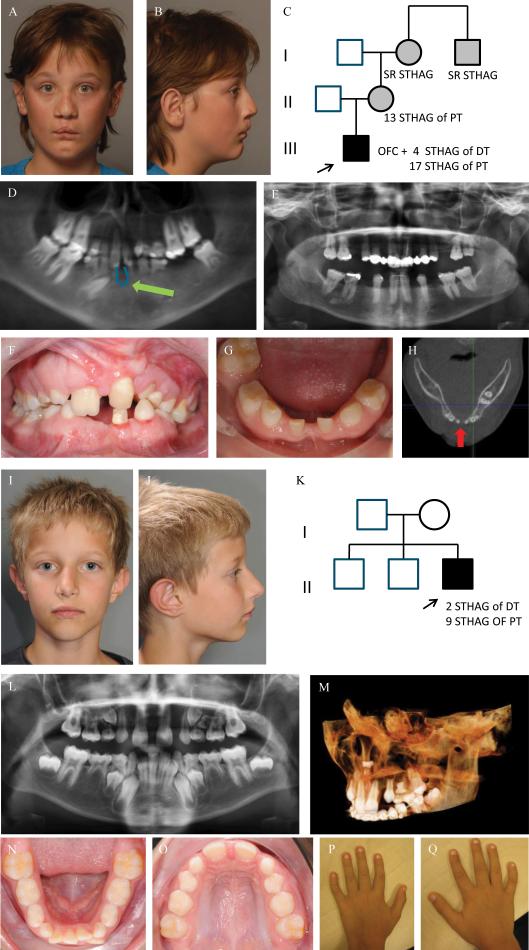

Figure 1. Clinical photographs, orthopantomogram (OPT), image from Cone Beam Computer Tomogram (CBCT) and pedigree of index patient 1 (A-H) and of index patient 2 (I-Q).

Frontal and lateral facial photographs of index patient 1 at 12 yrs of age (A-B), showing a repaired bilateral cleft lip with a left-sided cleft alveolus and a complete cleft of the anterior and posterior palate. He has a wide nasal base, full nasal tip, wide nasal bridge (H) and has a dip in the chin (A, B). His mother, maternal grandmother and her brother also have TA, but no other orofacial abnormalities (C). The patient presents with severe TA or oligodontia: he had agenesis of 4 deciduous teeth (#52, #62, #72 and #82) and misses 18 teeth in the permanent dentition, 17 due to tooth agenesis (#15, #14, #13, #12, #22, #23, #24, #25, #35, #34, #33, #32, #31, #41, #42, #44, #45) (excluding third molars) and 1 (#36) due to extraction. (D). He has a small median mandibular cleft, which can be seen on the orthopantomogram (OPT) at the green arrow (D), the intraoral photographs (F,G) and on the horizontal tomographic view of a CBCT (H). The OPT of the boy's mother shows severe TA, as she misses 13 permanent teeth.

Frontal and lateral photographs of the index patient 2 at 9 yrs of age (I-J) showing mild facial dysmorphic features including a narrow nasal ridge, posteriorly rotated ears with a thin helix, small earlobes, and a long superior crus antihelix. He has unaffected parents and two unaffected brothers (K). The OPT shows tooth agenesis (TA) of two deciduous teeth (#52, #62) and of nine permanent teeth (#17, #15, #14, #12, #22, #25, #27, #35, #45) (L). There is an ectopic tooth germ in the upper right molar area (#17 or #18) and a horizontally impacted premolar germ (#24) in the left upper quadrant (L-M). The occlusal photograph of the mandibular dental arch in the mixed dentition shows malposition of tooth #32 (N). The shape of the palatal cusps of teeth #16 and #26 are abnormal, making them resemble a second molar on the occlusal photograph of the maxillary dental arch (O). He has clinodactyly of the 5th fingers (P-Q).

Abbreviations used: STHAG, selective tooth agenesis; DT, deciduous teeth; PT, permanent teeth

The second index patient had agenesis of 2 deciduous and 9 permanent teeth (Figure 1. I-Q). Other dental features included impaction of tooth #24 and conic tooth shape of #13 and #23. He has clinodactyly of the fifth fingers and hypermobile joints.

From both patients and their parents we obtained written consent for publication of their photographs (Figure 1.).

For the full phenotype description and medical family history in both index patients, we refer to Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Whole Exome Sequencing

Two protocols for Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) and subsequent data analysis were used in the two index patients. The first one was performed through the Baylor-Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics using the methods previously reported9 , while the second was performed in a clinical setting at the Department of Human Genetics of the Radboud University Medical Center similar to previous reports.10

To identify additional patients with LRP6 variants, 29 in-house diagnostic exomes performed in patients with a range of craniofacial disorders were queried for rare (<1% in dbSNP141), non-synonymous and canonical splice site variants in LRP6.

Immunohistochemistry for Lrp6 in mouse head

To check the expression of Lrp6 in mouse developing tooth and palate, we generated paraffin sections of E13 and E15 mouse embryo heads and stained them with anti-Human LRP6 polyclonal antibody (cat. nr.orb18907, Progen, Sanbio, the Netherlands) counterstained with Hematoxylin.

Regulation of Lrp6 by Trp63

We checked for Trp63 binding sites in Lrp6 using ChIP-qPCR analysis. To generate additional evidence for regulation of Lrp6 by Trp63 the expression of Lrp6 in facial processes of Trp63−/− embryos was compared to their wild-type littermates. The breeding of the genetically-modified mice was performed after ethical review and in accordance with the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986, UK.

Re-sequencing with molecular inversion probes

To genetically test our hypothesis on the contribution of rare LRP6 coding variants to the etiology of TA and of common OFC, we aimed to re-sequence all exons of LRP6 in a large patient cohort, as well as in controls. Molecular inversion probes (MIPs) were used to re-sequence LRP6 in 67 cases with TA,11 1,073 cases with OFC, and in 706 controls (CO). Cases and controls were part of the sample collection efforts from Bonn (OFC, CO), Nijmegen (OFC) and Leuven (OFC, TA) respectively (Table S1).

Ethical approval by the Institutional Review Boards involving Human Subjects and the Ethical Committees of the respective University Hospitals was obtained, as well as written informed consent from all individuals.

A total of 69 MIPs were designed for the coding exons of LRP6 and used for targeted enrichment as previously described6 with minor modifications. All coding exons of LRP6 were covered on average 1045±480-fold (average ± standard deviation) per sample. This was comparable for cases (1,040-fold) and controls (1,051-fold) (Supplementary Materials and Methods). The identified variants were filtered using the same filter steps for cases and controls (Table 1).

Table 1. Overview of LRP6 variants identified with MIP screen in OFC and TA patients vs. controls.

All variants were coding or canonical splice site variants with a population frequency of <0.1% (based on dbSNP142 and an in-house database with >5,000 samples), ≤3 samples in this study with the same variant and a ‘GATK quality by depth’ of >1,000, the latter was based on previous MIP data and extensive validations by Sanger sequencing showing low false positive rates and high sensitivity. Minimal average coverage over all MIPs of included samples was 100-fold. Most unique and rare non-synonymous variants reported here in cases have been validated by Sanger sequencing.

| Total cases w. variant (n=1139) | TA cases w. variant (n=67) | OFC cases w. variant (n=1072) | Controls w. variant (n=706) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rare (<0.1%) coding & SS$ variants | 30 | 8 | 22 | 16 |

| Of which synonymous | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Of which non-synonymous | 27 | 7a | 20b | 13a,b |

| Unique/private variants | 13 | 5 | 8 | 5 |

| Of which synonymous | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Of which non-synonymous | 12 | 5c | 7d | 3c,d |

| Of which CADD PHRED >20 | 7 | 4e | 3f | 1e,f |

Splice site canonical dinucleotide; CADD PHRED-like score (Kircher et al. 2014, Nature Genetics).

7 rare, non-synonymous variants in LRP6 in 67 cases with OD were highly significant when compared to the variant load in 706 controls (Fisher's exact test after Bonferroni correction P = 0.0056022); while 20 rare, non-synonymous variants in LRP6 in 1072 cases with OFC does not show significance when compared to the variant load in 706 controls.

5 unique, non-synonymous variants in LRP6 in 67 cases with OD were highly significant when compared to 3 such variants in 706 controls (Fisher's exact test after Bonferroni correction P = 0.0012354); while 7 unique, non-synonymous variants in LRP6 in 1072 cases with OFC does not show significance when compared to the variant load in 706 controls.

4 unique, predicted damaging variants in LRP6 in 67 cases with OD were highly significant when compared to 1 such variant in 706 controls (Fisher's exact test after Bonferroni correction P = 0.001515); while 7 unique, non-synonymous variants in LRP6 in 1073 cases with OFC does not show significance when compared to the variant load in 706 controls.

RESULTS

Exome sequencing of index patients 1 and 2

After filtering for rare coding variants found with WES (Table S2) we identified a deleterious frameshift (c.4594delG, p.Cys1532fs) and a canonical splice site mutation (c.3398-2A>C, p.?) in LRP6 respectively in index patient 1 with severe TA and OFC, and in the unrelated index patient 2 with severe TA only. The frameshift mutation was predicted to cause a premature stop 15 codons downstream. As this mutation is located in the last exon of LRP6 (Figure S1 ), the mRNA is predicted to escape nonsense-mediated decay, resulting in a truncated protein missing all terminal phosphorylation domains (PPPSP) domains and thereby disrupting further downstream Wnt signaling. LRP6 mutants lacking two of the five PPPSP motifs are mostly inactive.12

The canonical splice site mutation was located at a highly conserved canonical splice acceptor of intron 15, and is predicted to severely disrupt splicing (Table S2; Figure S1). Based on their location, conservation, protein function and segregation, these LRP6 mutations were considered causal for the two patients’ tooth agenesis phenotypes.

Immunohistochemistry for Lrp6 in mouse head

Immunohistochemistry staining of Lrp6 on sections of the embryonic mouse heads (Figure S2A,B) show that Lrp6 is expressed in areas of bone formation already at E13 (Figure S2A) but more clearly and including palatal bone at E15 (Figure S2B). Interestingly, Lrp6 is expressed in tooth follicle, especially in the inner enamel epithelium (Figure S2B), suggesting a role for Lrp6 in early tooth development.

Regulation of Lrp6 by Trp63

A functional Trp63 binding site is present in intron 7 of Lrp6 using ChIP-qPCR analysis (Figure S2C). Although Lrp6 expression is down-regulated in the facial processes of Trp63−/− embryos compared to their wild-type littermates, this reduction was not significant (Figure S2D,E). Furthermore, Lrp6 displayed reduced expression within the mesenchyme of E11.5 medial nasal processes between Trp63+/+ and Trp63−/− embryos (data not shown), but this effect was subtle.

Re-sequencing with molecular inversion probes

Only for cases with TA, a significant enrichment of rare variants was found compared to controls (7/67 vs. 13/706; Fisher's exact test after Bonferroni correction P = 0.0056022 (Table 1)) with a similar significant enrichment when considering unique variants (5/67 vs. 3/706; P = 0.0012354) or predicted damaging variants (CADD PHRED-like score >20) (4/67 vs. 1/706; P = 0.001515). There was no difference between cases and controls for rare or unique synonymous variants. There was no statistically significant enrichment for unique LRP6 variants in OFC cases compared to controls.

All unique variants in TA cases were validated by Sanger sequencing and segregation analysis showed segregation in all families (Figure S3A-E), hence all five variants were considered likely pathogenic (Table S3A). These contained two canonical splice site variants as well as three missense variants. Of note, the sporadic case, TA2, shows a de novo mutation. Based on the gene specific mutation rates from Samocha et al.13 the chance of identifying a de novo missense mutation in LRP6 in 67 TA cases is extremely low (P = 0.006076 Exact Poisson Test). The ultimate proof of pathogenicity of the presented missense variants will require additional functional evidence.

Careful inspection of all medical records of the seven described cases harboring unique LRP6 mutations (Figure S4; Table S3B) revealed additional dental anomalies like tooth ankylosis (n=2), abnormal tooth shape (n=2), enamel defects (n=1), and other symptoms like clinodactyly (n=3). Furthermore, growth hormone supplementation therapy (GHST) was being considered in 4 of these 7 patients.

Severe TA was also present in a patient carrying a rare LRP6 variant (Figure S3F, Figure S4J,K). This suggests that several of the rare variants may still be involved in the phenotype.

DISCUSSION

We here report that loss of function of LRP6 causes tooth agenesis. The Low Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein 6 is a transmembrane cell surface protein, member of the low density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor gene family. LRP6 acts as a co-receptor for WNT together with Frizzled (FZD), transmitting signals in the canonical WNT/β-catenin-TCF signaling cascade which is well known for its role in differentiation, proliferation and migration processes during dental and orofacial development. Two genes of this pathway have already been implicated in human TA. Mutations in AXIN2 [MIM: #608615] were associated with tooth agenesis-colorectal cancer predisposition and mutations in WNT10A can cause either isolated4 or syndromic tooth agenesis [WNT10A; MIM:*606268]. Lrp6 is described to positively regulate WNT/β-catenin signaling by Wnt receptor internalization (GO:0038013) in LRP6 signalosomes.14

Our findings on tooth agenesis further expand the spectrum of LRP6 phenotypes. While loss- or gain-of-function mutations in LRP6 and in another closely resembling Wnt co-receptor, LRP5, had already put the Wnt pathway central in bone biology, Wnt had emerged as an important regulator of skeletal modeling and remodeling.15 LRP6 is also key to parathyroid hormone (PTH) signaling which regulates osteoblast activity; PTH binds to its receptor PTH1R and thereby induces the PTH-PTH1R-LRP6 protein complex, leading to increased bone formation in rat.16 As LRP6 mutations may disrupt this PTH-PTH1R-LRP6 interaction, effects on growth could result. This could explain why GHST was considered in 4 of our 7 patients with unique LRP6 mutations. Other human diseases related to LRP6 variants include atherosclerosis17, osteoporosis15 and metabolic syndrome.18 Recently, rare LRP6 mutations were also reported in spina bifida.19

Although, genetic inactivation of Lrp6 was also reported to lead to cleft lip with cleft palate in a mouse model,20 our genetic data do not support a role for LRP6 mutations in nonsyndromic OFC in humans. Moreover our functional data fail to show significant regulation of Lrp6 by Trp63. As we only found evidence for molecular underpinning of TA by LRP6 mutations, it remains unsolved whether the LRP6 mutation in our index patient with combined TA-OFC also contributed to the OFC development in this patient.

Based on our results an estimate can be made on the frequency of LRP6 mutations in the normal population, as frequencies of TA in general populations are known. In our cohort 3 in 706 control individuals (0.4%) were carriers of unique LRP6 variants. Although this frequency matches with population frequencies for severe TA ranging between 0.1-0.5%, it remains unclear whether those variants are pathogenic. We hypothesize that LRP6 is a major cause of severe TA, rather than causing common TA (3% to 20% in populations worldwide).

In conclusion, we show that LRP6 mutations cause severe tooth agenesis with or without other dental anomalies like ankylosis, enamel defects and tooth shape anomalies. Our genetic data however don't provide evidence that rare monogenic LRP6 mutations underlie non-syndromic orofacial clefts.

Post-review comment

During the review process of the current study, the following manuscript was published : Massink MP, et al. Loss-of-Function Mutations in the WNT Co-receptor LRP6 Cause Autosomal-Dominant Oligodontia. Am J Hum Genet. 2015 Oct 1;97(4):621-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.08.014. Epub 2015 Sep 17. This study provides additional independent evidence for the causative role of LRP6 mutations in tooth agenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Members of the Nijmegen Cleft Lip and Palate Team, Dr R. Admiraal, Dr W. Borstlap, Dr T. Wagner, Dr M. Nienhuis, Mrs V. Engels, Drs M. Kuijpers, Mrs J. Vanderstappen, Mrs E. Kerkhofs, em Prof. dr AM Kuijpers-Jagtman, Mrs M. Nijhuis, Mrs J. Buchner and Mrs M. van der Looy. All the affected individuals, their parents, families and control individuals from Bonn, Leuven and Nijmegen who participated in this study.

Sources of funds:

The Center for Mendelian Genomics is supported by the National Institutes of Health National Human Genome Research Institute (Grants RO1NS058529 and U54HG006542 to J.R.L.).

Research in the Dixon laboratory, University of Manchester is supported by the Medical Research Council (G0901539 & MR/M012174/1 to M.D.).

European Orthodontic Society (048 EOS-Research Grant, 2010 to C.C.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary information is available at the Genetics in Medicine website.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schutte BC, Murray JC. The many faces and factors of orofacial clefts. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8(10):1853–1859. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.10.1853. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10469837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polder BJ, Van't Hof MA, Van der Linden FP, Kuijpers-Jagtman AM. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of dental agenesis of permanent teeth. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32(3):217–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00158.x. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.OMIM (Online Mendelian inheritance in man) Johns Hopkins University, Center for Medical Genetics; Baltimore: 1996. http://www3.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/(September) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van den Boogaard MJ, Creton M, Bronkhorst Y, et al. Mutations in WNT10A are present in more than half of isolated hypodontia cases. J Med Genet. 2012;49(5):327–331. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-100750. doi:10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-100750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van den Boogaard MJ, Dorland M, Beemer F a, van Amstel HK. MSX1 mutation is associated with orofacial clefting and tooth agenesis in humans. Nat Genet. 2000;24(4):342–3. doi: 10.1038/74155. doi:10.1038/74155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liang J, Zhu L, Meng L, Chen D, Bian Z. Novel nonsense mutation in MSX1 causes tooth agenesis with cleft lip in a Chinese family. Eur J Oral Sci. 2012;120(4):278–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2012.00965.x. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0722.2012.00965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matalova E, Fleischmannova J, Sharpe PT, Tucker AS. Tooth Agenesis: from Molecular Genetics to Molecular Dentistry. J Dent Res. 2008;87(7):617–623. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700715. doi:10.1177/154405910808700715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howe BJ, Cooper ME, Vieira a. R, et al. Spectrum of Dental Phenotypes in Nonsyndromic Orofacial Clefting. J Dent Res. 2015;94(7):905–912. doi: 10.1177/0022034515588281. doi:10.1177/0022034515588281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lupski JR, Gonzaga-Jauregui C, Yang Y, et al. Exome sequencing resolves apparent incidental findings and reveals further complexity of SH3TC2 variant alleles causing Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy. Genome Med. 2013;5(6):57. doi: 10.1186/gm461. doi:10.1186/gm461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Ligt J, Willemsen MH, van Bon BWM, et al. Diagnostic exome sequencing in persons with severe intellectual disability. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(20):1921–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1206524. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1206524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dreesen K, Swinnen S, Devriendt K, Carels C. Tooth agenesis patterns and phenotype variation in a cohort of Belgian patients with hypodontia and oligodontia clustered in 79 families with their pedigrees. Eur J Orthod. 2014;36(1):99–106. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjt021. doi:10.1093/ejo/cjt021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacDonald BT, Yokota C, Tamai K, Zeng X, He X. Wnt signal amplification via activity, cooperativity, and regulation of multiple intracellular PPPSP motifs in the Wnt co-receptor LRP6. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(23):16115–16123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800327200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M800327200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samocha KE, Robinson EB, Sanders SJ, et al. A framework for the interpretation of de novo mutation in human disease. Nat Genet. 2014;46(9):944–950. doi: 10.1038/ng.3050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bilic J, Huang Y-L, Davidson G, et al. Wnt induces LRP6 signalosomes and promotes dishevelled-dependent LRP6 phosphorylation. Science. 2007;316(5831):1619–22. doi: 10.1126/science.1137065. doi:10.1126/science.1137065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams BO, Insogna KL. Where Wnts went: the exploding field of Lrp5 and Lrp6 signaling in bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24(2):171–178. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.081235. doi:10.1359/jbmr.081235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wan M, Yang C, Li J, et al. Parathyroid hormone signaling through low-density lipoprotein-related protein 6. Genes Dev. 2008;22(21):2968–2979. doi: 10.1101/gad.1702708. doi:10.1101/gad.1702708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mani A, Radhakrishnan J, Wang H, et al. LRP6 mutation in a family with early coronary disease and metabolic risk factors. Science. 2007;315(5816):1278–1282. doi: 10.1126/science.1136370. doi:10.1126/science.1136370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh R, Smith E, Fathzadeh M, et al. Rare nonconservative LRP6 mutations are associated with metabolic syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2013;34(9):1221–1225. doi: 10.1002/humu.22360. doi:10.1002/humu.22360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lei Y, Fathe K, McCartney D, et al. Rare LRP6 variants identified in spina bifida patients. Hum Mutat. 2015;36(3):342–349. doi: 10.1002/humu.22750. doi:10.1002/humu.22750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song L, Li Y, Wang K, et al. Lrp6-mediated canonical Wnt signaling is required for lip formation and fusion. Development. 2009;136(18):3161–3171. doi: 10.1242/dev.037440. doi:10.1242/dev.037440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.