Abstract

Msh homeobox 1 (MSX1) encodes a transcription factor implicated in embryonic development of limbs and craniofacial tissues including bone and teeth. Although MSX1 regulates osteoblast differentiation in the cranial bone of young animal, little is known about the contribution of MSX1 to the osteogenic potential of human cells. In the present study, we investigate the role of MSX1 in osteogenic differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells isolated from deciduous teeth. When these cells were exposed to osteogenesis-induction medium, runt-related transcription factor-2 (RUNX2), bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP2), alkaline phosphatase (ALPL), and osteocalcin (OCN) mRNA levels, as well as alkaline phosphatase activity, increased on days 4–12, and thereafter the matrix was calcified on day 14. However, knockdown of MSX1 with small interfering RNA abolished the induction of the osteoblast-related gene expression, alkaline phosphatase activity, and calcification. Interestingly, DNA microarray and PCR analyses revealed that MSX1 knockdown induced the sterol regulatory element-binding protein 2 (SREBP2) transcriptional factor and its downstream target genes in the cholesterol synthesis pathway. Inhibition of cholesterol synthesis enhances osteoblast differentiation of various mesenchymal cells. Thus, MSX1 may downregulate the cholesterol synthesis-related genes to ensure osteoblast differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells.

1. Introduction

Msh homeobox 1 (MSX1) is a homeobox transcriptional factor involved in limb-pattern formation and craniofacial development and specifically in odontogenesis. Mouse Msx1 mutations cause craniofacial malformation and tooth agenesis [1]. Msx1-knockout mice show arrested tooth development at the bud stage and embryonic lethal defects [2]. Msx1 is expressed at high levels in craniofacial skeletal cells during early postnatal development [3], and transgenic mice expressing Msx1 under the control of the alpha (I) collagen promoter exhibit increased osteoblast number, cell proliferation, and apoptosis [4], suggesting Msx1 may have a role in craniofacial bone modeling. MSX1 is also expressed at high levels in the dental mesenchyme at the cap and bell stages [5] and may be a suppressor for cell differentiation that maintains mesenchymal cells in a proliferative state to ensure robust craniofacial and tooth development [6]. In addition, MSX1 is an upstream and downstream regulator for the bone morphogenetic protein BMP2/BMP4 signaling pathway [7, 8]. Mutations in human MSX1 also cause cleft lip/palate and tooth agenesis [9, 10]. However, the role of MSX1 in human craniofacial and tooth development has not been fully understood.

Dental pulp stromal cells isolated from whole pulp tissue can differentiate into osteoblasts, odontoblasts, endothelial cells, nerve cells, and adipocytes in vitro. Some of these cells identified by several cell surface antigens are referred to as dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) [11, 12]. DPSCs may play a role in dentinogenesis/osteogenesis in both developing and injured teeth. Furthermore, these cells are a promising source of cell-based regenerative therapies for dental, skeletal, vascular, and neuronal diseases [13, 14]. Human DPSCs (hDPSCs) have not been fully characterized at the molecular level, but a previous reported showed that MSX1 is expressed at higher levels in hDPSCs than in bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells and fibroblasts [15]. MSX1 may participate in the control of primary or secondary dentin formation and reparative dentin or osteodentin/bone formation in injured pulp tissue, in addition to the physiological role such as the maintenance of dental pulp stem/progenitor cells in healthy teeth. In the present study, we explored the role of MSX1 in pulpal mesenchymal cells using human DPSCs in culture.

Statins are a class of drugs that function as specific inhibitors of 3-hydoroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA) reductase, a rate-limiting enzyme in cholesterol synthesis. Numerous studies have shown that statins exert bone anabolic effects in osteoblasts and osteogenic precursor cells [16, 17]. Simvastatin enhances alveolar bone remodeling in the tooth extraction socket [18], enhances bone fracture healing [19], and reduces alveolar bone loss and tooth mobility in chronic periodontitis [20]. In addition, simvastatin enhances odontoblast/osteoblast differentiation of DPSCs and mesenchymal stem cells isolated from other tissues [17, 21, 22]. These studies indicate a close relationship between cholesterol synthesis and osteoblast differentiation.

Here, we demonstrated the role of MSX1 in osteoblast differentiation and cholesterol synthesis in hDPSCs using small interfering RNA (siRNA) against MSX1. DNA microarray analyses revealed that knockdown of MSX1 in hDPSCs undergoing osteogenic differentiation abolished the expression of various osteoblast-related genes but enhanced the expression of cholesterol synthesis-related genes. Our results suggest that MSX1 enhances osteoblast differentiation and calcification in hDPSCs through repression of cholesterol synthesis genes and induction of osteoblast-related genes.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Human DPSCs

Extracted healthy deciduous teeth were collected from 6–12-year-old children following protocols approved by the ethical authorities at Hiroshima University (permit number: D88-2). Written informed consent was obtained from the subject or subject's parent. Pulp tissue specimens from deciduous teeth were minced and digested with 3 mg/mL collagenase type I (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 4 mg/mL dispase (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 1 h at 37°C. Single cell suspension was obtained by passing cells through a 70 μm cell strainer (CORNING, Corning, NY, USA). The cells were incubated in DMEM supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Biowest, Nuaillé, France) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Life Technologies) at 37°C in 95% air and 5% CO2 [23]. Forming colonies were separated by incubation with Accutase (Funakoshi Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), and isolated cells were transferred to passage cultures with DMEM supplemented by 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. The culture medium was changed every 2 days. Cells at passages 3–9 were used in subsequent experiments.

2.2. FACS Analysis

Cells were harvested with Accutase and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Cells were centrifuged at 1,500 ×g for 5 min and resuspended at 5 × 106 cells/mL in PBS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Aliquots containing 105 cells were incubated with individual phycoerythrin- (PE-) conjugated antibodies or isotype control PE-conjugated IgGκ for 30 min at room temperature and then washed in PBS supplemented with 3% FBS. Samples were analyzed using a FACS Aria flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and the data were analyzed using CELLQUEST software (Becton Dickinson). The following monoclonal antibodies were used: PE-conjugated antibodies against CD73 (mouse IgG1κ; Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA), CD90 (mouse IgG1κ; Biolegend), CD105 (mouse IgG1κ; Biolegend), and CD166 (mouse IgG1κ; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Texas, USA). PE-conjugated isotype control mouse IgG1κ (Biolegend) was used as the control.

2.3. MSX1 Knockdown

MSX1 siRNA oligonucleotides (s8999 and s224066) were purchased from Life Technologies. The sequences are 5′-GCAUUUAGAUCUACACUCUtt-3′ (sense) and 5′-AGAGUGUAGAUCUAAAUGCta-3′ (antisense) for s8999 and 5′-GCAAGA AAAGCGCAGAGAAtt-3′ (sense) and 5′-UUCUCUGCGCUUUUCUUGCct-3′ (antisense) for s224066. Silencer select negative control #1 siRNA (Life Technologies) was used as the control.

Human DPSCs were seeded at 5 × 104 cells/well in 24-multiwell plates coated with type I collagen with 0.5 mL DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. After 24 h, siRNA was transfected into cells with Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) and cells were incubated for an additional 48 h.

2.4. Osteogenic Differentiation of hDPSCs and Alizarin Red Staining

After the cultures became confluent, hDPSCs were incubated with 0.5 mL of DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate (Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid 2-phosphate (Sigma), 2 mM L-glutamine (Sigma), 100 nM dexamethasone (Sigma), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (osteogenesis-induction medium) as described [15]. For evaluation of calcification, cells incubated with osteogenesis-induction medium for 14 days were fixed at room temperature in 95% ethanol for 10 min and stained with 1% alizarin red S for 30 min. The cell-matrix layers were washed 6 times with sterile water.

2.5. Alkaline Phosphatase Activity

Human DPSCs were washed twice with saline and homogenized ultrasonically with 1% NP-40 in saline. Alkaline phosphatase activity was determined using Lab Assay ALP (Wako, Osaka, Japan). DNA concentration was determined with the Quant-iT™ PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (Life Technologies) to calculate alkaline phosphatase activity/μg DNA.

2.6. Reverse Transcription-Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated and cDNA was synthesized as described [15]. The cDNA samples were amplified using Universal PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies) with primers (Table 1) and TaqMan probes were purchased from Roche Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). GAPDH primers/probe set was used for normalization. After amplification of DNA, expression levels were determined with the ABI prism 7900 HT sequence detection system (Life Technologies).

Table 1.

Primer and probe sequences used for RT-qPCR.

| Gene | Primer (5′ → 3′) | Probe |

|---|---|---|

| MSX1 (sense) | F: CTCGTCAAAGCCGAGAGC | Roche Universal Probe # 7 |

| R: CGGTTCGTCTTGTGTTTGC | ||

| MSX1 (antisense) | F: GCCAGCCCTCTTAGAAACAG | Roche Universal Probe # 50 |

| R: AATAAAGCAGCCCCTCGTTC | ||

| RUNX2 | F: CAGTGACACCATGTCAGCAA | Roche Universal Probe # 66 |

| R: GCTCACGTCGCTCATTTTG | ||

| BMP2 | F: CGGACTGCGGTCTCCTAA | Roche Universal Probe # 49 |

| R: GGAAGCAGCAACGCTAGAAG | ||

| OSX | F: CAGCAGCTAAACTTGGAAGGA | Roche Universal Probe # 76 |

| R: TGCTTTCGCTTGTCTGAGTC | ||

| OCN | F: GCCTCCTGAAAGCCGATGT | 5′-CCAACTCGTCACAGTCCGGATTGAGCT-3′ |

| R: AAGAGACCCAGGCGCTACCT | ||

| ALPL | F: TCACTCTCCGAGATGGTGGT | Roche Universal Probe # 12 |

| R: GTGCCCGTGGTCAATTCT | ||

| SOX9 | F: GTACCCGCACTTGCACAAC | Roche Universal Probe # 61 |

| R: TCTCGCTCTCGTTCAGAAGTC | ||

| PPARγ | F: GACAGGAAAGACAACAGACAAATC | Roche Universal Probe # 7 |

| R: GGGGTGATGTGTTTGAACTTG | ||

| SREBP2 | F: GCCCTGGAAGTGACAGAGAG | Roche Universal Probe # 21 |

| R: TGCTTTCCCAGGGAGTGA | ||

| HMGCS1 | F: TCTGTCTACTGCAAAAAGATCCAT | Roche Universal Probe # 59 |

| R: TGAAGCCAAAATCATTCAAGG | ||

| HMGCR | F: GTTCGGTGGCCTCTAGTGAG | Roche Universal Probe # 65 |

| R: GCATTCGAAAAAGTCTTGACAAC | ||

| FDPS | F: GGCCACTCCAGAACAGTACC | Roche Universal Probe # 75 |

| R: CCTCATATAGCGCCTTCACC | ||

| CYP51A1 | F: TGCAGATTTGGATGGAGGTT | Roche Universal Probe # 64 |

| R: CCTTGATTTCCCGATGAGC | ||

| DHCR7 | F: GCCATGGTCAAGGGCTAC | Roche Universal Probe # 60 |

| R: TTGTAAAAGAAATTGCCTGTGAAT |

MSX1: msh homeobox 1; RUNX2: runt-related transcription factor-2; BMP2: bone morphogenetic protein-2; OSX: osterix; OCN: osteocalcin; ALPL: alkaline phosphatase liver type; SOX9: SRY- (sex determining region Y-) box 9; PPARγ: peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma; SREBP2: sterol regulatory element-binding protein 2; HMGCS1: 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase 1; HMGCR: HMG-CoA reductase; FDPS: farnesyl diphosphate synthase; CYP51A1: Cytochrome P450 Family 51 Subfamily A Polypeptide 1; DHCR7: 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase; F: forward; R: reverse.

2.7. DNA Microarray

After the induction of osteogenic differentiation for 4 days, total RNA was isolated from MSX1-knockdown and control hDPSCs using TRIzol (Life Technologies, Japan) and an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA). DNA microarray analysis was performed using the SurePrint G3 Human GE 8 × 60 K v2 Microarray (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Raw data were standardized by the global median normalization method using GeneSpring (Silicon Genetics, Redwood City, CA, USA). The raw data were deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (GSE69992).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SD. Differences between two groups were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test for multiple comparisons. In all analyses, P < 0.05 indicated statistically significant differences between values.

3. Results

3.1. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Markers Expressed in Cultured hDPSCs

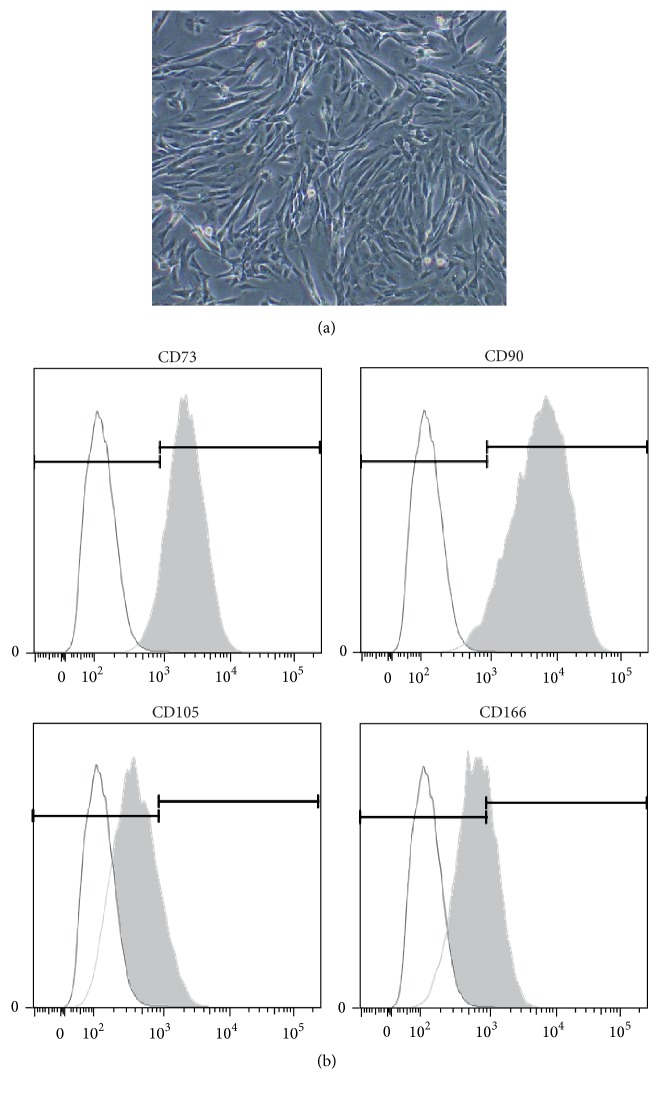

Human DPSCs from postnatal human primary teeth were used to explore the functional role of MSX1. These cells exhibited a fibroblastic shape (Figure 1(a)) and showed expression of mesenchymal stem cell surface markers CD73 (>90%), CD90 (>90%), CD105 (>10%), and CD166 (>30%) (Figure 1(b)) as expected from previous studies [24].

Figure 1.

(a) A microscope image of cultured hDPSCs isolated from human primary teeth with no induction. (b) Positive expression of several cell surface antigens for mesenchymal stem cells, including CD73, CD90, CD105, and CD166, in hDPSCs. Similar cell surface antigen expression pattern was obtained with hDPSCs isolated from different donors (data not shown).

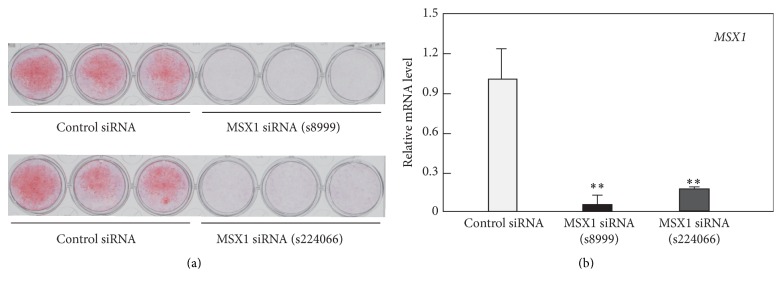

3.2. MSX1 Knockdown Abolishes Osteogenic Differentiation of hDPSCs

Human DPSCs were transfected with two different siRNAs for MSX1 or control siRNA and then exposed to osteogenesis-induction medium. Both siRNA oligonucleotides targeting MSX1 (s8999 and s224066) abolished MSX1 mRNA expression at 48 h and subsequent matrix calcification on day 14 (Figure 2). We selected MSX1 siRNA (s8999) for subsequent studies.

Figure 2.

Effects of MSX1 knockdown on calcification of hDPSCs. hDPSCs were transfected with either MSX1 siRNA (s8999 or s224066) or control siRNA and incubated for 2 days in growth medium before the cultures became confluent. Thereafter, the cultures were exposed to osteogenesis-induction medium. (a) The calcified matrix was stained with alizarin red on day 14. (b) MSX1 mRNA level was quantified by RT-qPCR at 48 h after transfection. Values are averages ±SD for three cultures. ∗∗ P < 0.01.

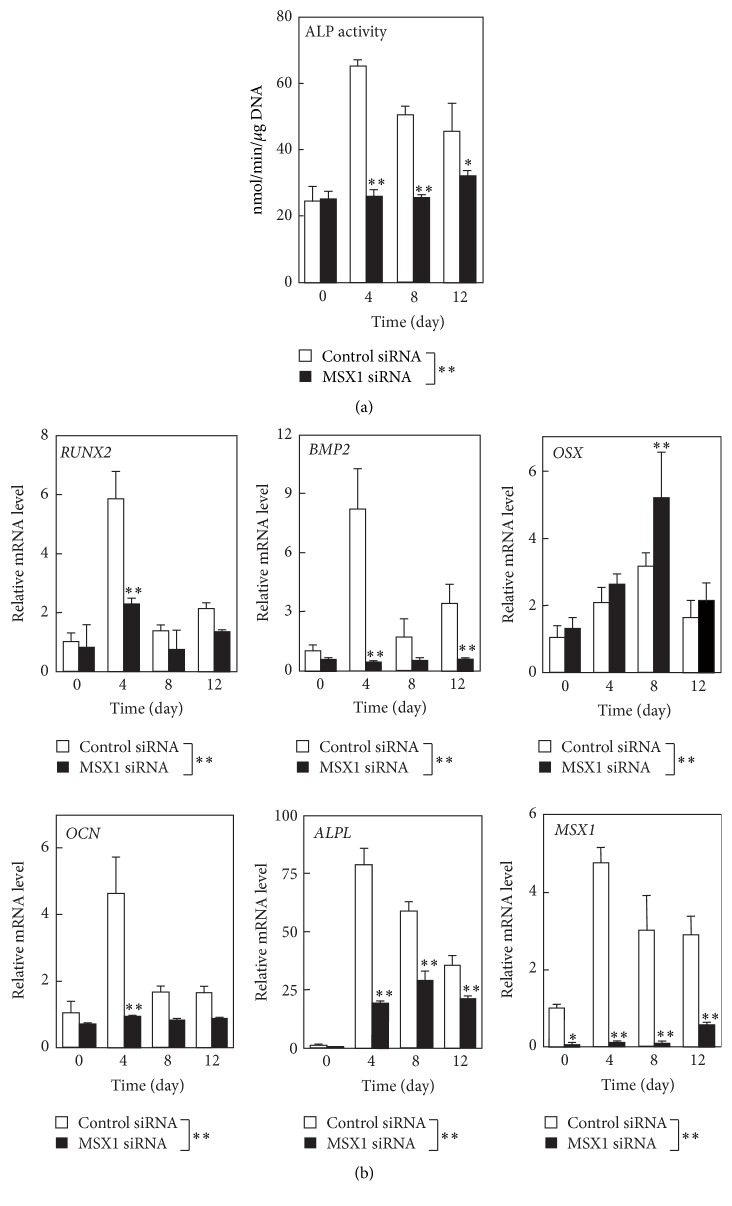

Next, we examined the effect of MSX1 knockdown on alkaline phosphatase activity and the expression of osteoblast-related genes in hDPSCs after the onset of osteogenesis (Figure 3). In hDPSCs transfected with control siRNA, alkaline phosphatase activity and RUNX2, BMP2, osterix (OSX), osteocalcin (OCN; also known as BGLAP), and alkaline phosphatase liver type (ALPL) mRNA levels increased on days 4–12 after the onset of differentiation. MSX1 mRNA levels also increased on days 4–12. However, MSX1 knockdown abolished the induction of alkaline phosphatase activity (Figure 3(a)) and the increases in ALPL, RUNX2, BMP2, OCN, and MSX1 mRNA levels, although it further increased OSX mRNA levels (Figure 3(b)). It should be noted that the incubation with MSX1 siRNA abolished MSX1 expression at least until day 12 after the onset of osteogenic differentiation.

Figure 3.

Effects of MSX1 knockdown on the expression of osteogenic markers in hDPSCs. (a) Alkaline phosphatase activity in cultures was determined on days 0–12 after exposure to osteogenesis-induction medium. (b) The mRNA levels of osteoblast-related genes, including RUNX2, BMP2, OSX, OCN, and ALPL, along with the MSX1 mRNA level were quantified by RT-qPCR on the indicated days. Values are averages ±SD for three cultures. ∗ P < 0.05; ∗∗ P < 0.01.

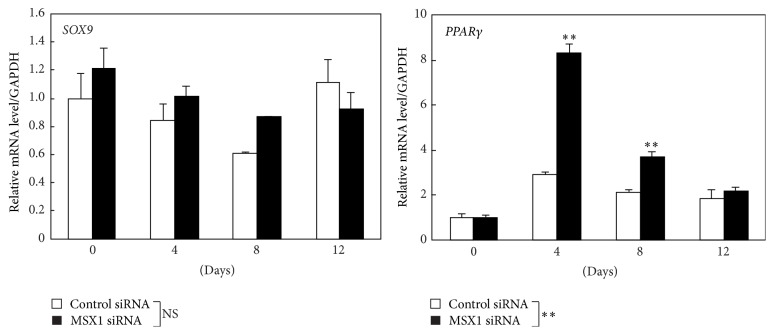

Next, we examined whether MSX1 knockdown might influence the expression of other master genes including a master regulator of chondrogenesis SOX9 and a master regulator of adipogenesis PPARγ (Figure 4). In control hDPSCs, no significant changes in the expressions of SOX9 and PPARγ were observed after the exposure to osteogenesis-induction medium. Under these conditions, MSX1 knockdown increased the expression of PPARγ on days 4–8, although it had little effect on the expression level of SOX9.

Figure 4.

Effects of MSX1 knockdown on the expression of the master genes of chondrogenesis and adipogenesis in hDPSCs. The mRNA levels of SOX9 and PPARγ in hDPSCs transfected with MSX1 siRNA or control siRNA were quantified by RT-qPCR on the indicated days. Values are averages ±SD for 3 cultures. ∗∗ P < 0.01; NS: not significant.

3.3. MSX1 Knockdown Downregulated and Upregulated a Variety of Genes

To characterize the effects of MSX1 knockdown on osteogenic differentiation, we performed DNA microarray analyses on day 4 after exposure to osteogenesis-induction medium. MSX1 knockdown decreased and increased mRNA levels of 2923 and 3480 genes, respectively, which were selected with cut-off values of >1.5-fold change and t-test P < 0.05. Tables 2 and 3 show lists of downregulated and upregulated genes in MSX1-knockdown hDPSCs, respectively.

Table 2.

The list of downregulated genes in MSX1-knockdown cells (top 50).

| Gene symbol | Gene name | Gene ID | Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|

| C11orf96 | Chromosome 11 open reading frame 96 | NM_001145033 | 92.53 |

| JAM2 | Junctional adhesion molecule 2 | NM_021219 | 70.90 |

| MLC1 | Megalencephalic leukoencephalopathy with subcortical cysts 1 | NM_015166 | 65.56 |

| NPPC | Natriuretic peptide C | NM_024409 | 54.40 |

| CPXM1 | Carboxypeptidase X (M14 family), member 1 | NM_019609 | 51.08 |

| EFCC1 | EF-hand and coiled-coil domain containing 1 | NM_024768 | 44.56 |

| SFRP4 | Secreted frizzled-related protein 4 | NM_003014 | 43.96 |

| JAM2 | Junctional adhesion molecule 2 | NM_021219 | 38.31 |

| LOC200772 | Uncharacterized LOC200772 | NR_033841 | 34.41 |

| S100A8 | S100 calcium binding protein A8 | NM_002964 | 31.72 |

| JAM2 | Junctional adhesion molecule 2 | NM_001270408 | 31.42 |

| CPXM1 | Carboxypeptidase X (M14 family), member 1 | NM_019609 | 29.44 |

| SFRP4 | Secreted frizzled-related protein 4 | NM_003014 | 28.11 |

| KIT | v-kit Hardy-Zuckerman 4 feline sarcoma viral oncogene homolog | NM_000222 | 27.48 |

| CLCA2 | Chloride channel accessory 2 | NM_006536 | 24.88 |

| LINC00473 | Long intergenic nonprotein coding RNA 473 | NR_026860 | 24.34 |

| ST8SIA4 | ST8 alpha-N-acetyl-neuraminide alpha-2,8-sialyltransferase 4 | NM_005668 | 24.16 |

| TEX29 | Testis expressed 29 | NM_152324 | 23.52 |

| PTGDR2 | Prostaglandin D2 receptor 2 | NM_004778 | 23.31 |

| CXCL14 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 14 | NM_004887 | 22.63 |

| HS6ST2 | Heparan sulfate 6-O-sulfotransferase 2 | NM_001077188 | 22.61 |

| CHST15 | Carbohydrate (N-acetylgalactosamine 4-sulfate 6-O) Sulfotransferase 15 | NM_015892 | 21.84 |

| PIANP | PILR alpha associated neural protein | NM_153685 | 21.67 |

| SNAP25 | Synaptosomal-associated protein, 25 kDa | NM_003081 | 21.55 |

| CBLN2 | Cerebellin 2 precursor | NM_182511 | 21.30 |

| FRAS1 | Fraser syndrome 1 | NM_025074 | 21.24 |

| SECTM1 | Secreted and transmembrane 1 | NM_003004 | 20.76 |

| NFE2 | Nuclear factor, erythroid 2 | NM_006163 | 20.46 |

| GABBR2 | Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) B receptor, 2 | NM_005458 | 19.22 |

| MSX1 | Msh homeobox 1 | NM_002448 | 19.08 |

| SCARA5 | Scavenger receptor class A, member 5 (putative) | NM_173833 | 18.79 |

| PRSS35 | Protease, serine, 35 | NM_153362 | 18.60 |

| WNT2B | Wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 2B | NM_004185 | 17.95 |

| BMP2 | Bone morphogenetic protein-2 | NM_001200 | 17.63 |

| NDRG4 | NDRG family member 4 | NM_022910 | 17.39 |

| CRTAM | Cytotoxic and regulatory T cell molecule | NM_019604 | 16.80 |

| RASL12 | RAS-like, family 12 | NM_016563 | 15.91 |

| THBD | Thrombomodulin | NM_000361 | 15.26 |

| CHST1 | Carbohydrate (keratan sulfate Gal-6) sulfotransferase 1 | NM_003654 | 14.90 |

| DIO3OS | DIO3 opposite strand/antisense RNA (head to head) | NR_002770 | 14.81 |

| CCR1 | Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 1 | NM_001295 | 14.81 |

| TMEM35 | Transmembrane protein 35 | NM_021637 | 14.79 |

| HAS1 | Hyaluronan synthase 1 | NM_001523 | 14.68 |

| SCN1B | Sodium channel, voltage-gated, type I, beta subunit | NM_199037 | 14.34 |

| ADAMTS17 | ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 17 | NM_139057 | 14.12 |

| GALNT15 | UDP-N-acetyl-alpha-D-galactosamine:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 15 | NM_054110 | 13.86 |

| RHOH | Ras homolog family member H | NM_004310 | 13.80 |

| GPR68 | G protein-coupled receptor 68 | NM_003485 | 13.63 |

| TAC3 | Tachykinin 3 | NM_013251 | 13.37 |

| MIR1247 | MicroRNA 1247 | AF469204 | 13.13 |

Table 3.

The list of upregulated genes in MSX1-knockdown cells (top 50).

| Gene symbol | Gene name | Gene ID | Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|

| MLXIPL | MLX interacting protein-like | NM_032951 | 74.63 |

| CRLF1 | Cytokine receptor-like factor 1 | NM_004750 | 73.44 |

| ATP1A2 | ATPase, Na+/K+ transporting, alpha 2 polypeptide | NM_000702 | 69.84 |

| MAP2 | Microtubule-associated protein 2 | NM_002374 | 62.64 |

| PRODH | Proline dehydrogenase (oxidase) 1 | NM_016335 | 50.32 |

| LONRF3 | LON peptidase N-terminal domain and ring finger 3 | NM_001031855 | 30.84 |

| ERICH2 | Glutamate-rich 2 | XM_001714892 | 29.67 |

| DMD | Dystrophin | NM_004010 | 27.91 |

| SAA1 | Serum amyloid A1 | NM_000331 | 26.65 |

| CLDN20 | Claudin 20 | NM_001001346 | 24.19 |

| DMD | Dystrophin | NM_004021 | 21.88 |

| PLIN4 | Perilipin 4 | NM_001080400 | 21.64 |

| RLBP1 | Retinaldehyde binding protein 1 | NM_000326 | 21.22 |

| SAA2 | Serum amyloid A2 | NM_030754 | 20.98 |

| PARD6B | Par-6 family cell polarity regulator beta | NM_032521 | 19.56 |

| ANO3 | Anoctamin 3 | NM_031418 | 17.58 |

| KCNJ16 | Potassium inwardly rectifying channel, subfamily J, member 16 | NM_170741 | 17.41 |

| LOC284561 | Uncharacterized LOC284561 | XR_110828 | 16.52 |

| USP53 | Ubiquitin specific peptidase 53 | NM_019050 | 16.47 |

| CLGN | Calmegin | NM_004362 | 16.35 |

| USP53 | Ubiquitin specific peptidase 53 | NM_019050 | 16.15 |

| PLCE1-AS1 | PLCE1 antisense RNA 1 | NR_033969 | 15.15 |

| KLHDC7B | Kelch domain containing 7B | NM_138433 | 14.44 |

| PSG9 | Pregnancy specific beta-1-glycoprotein 9 | NM_002784 | 14.23 |

| ERICH2 | Glutamate-rich 2 | XM_001714892 | 13.66 |

| ANKRD1 | Ankyrin repeat domain 1 (cardiac muscle) | NM_014391 | 13.58 |

| PDE6A | Phosphodiesterase 6A, cGMP-specific, rod, alpha | NM_000440 | 13.23 |

| COL4A4 | Collagen, type IV, alpha 4 | NM_000092 | 12.98 |

| PLAC8 | Placenta-specific 8 | NM_016619 | 12.85 |

| BEST2 | Bestrophin 2 | NM_017682 | 12.72 |

| IP6K3 | Inositol hexakisphosphate kinase 3 | NM_054111 | 12.22 |

| DNAH2 | Dynein, axonemal, heavy chain 2 | NM_020877 | 12.07 |

| INHBB | Inhibin, beta B | NM_002193 | 11.63 |

| LOC100506544 | Uncharacterized LOC100506544 | AK057177 | 10.9 |

| TMEM125 | Transmembrane protein 125 | NM_144626 | 10.57 |

| ORM2 | Orosomucoid 2 | NM_000608 | 10.51 |

| PCSK9 | Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 | NM_174936 | 10.17 |

| CD200 | CD200 molecule | NM_001004196 | 9.99 |

| MFSD2A | Major facilitator superfamily domain containing 2A | NM_001136493 | 9.85 |

| IL8 | Interleukin 8 | NM_000584 | 9.80 |

| FMO6P | Flavin containing monooxygenase 6 pseudogene | NR_002601 | 9.60 |

| C6 | Complement component 6 | NM_000065 | 9.54 |

| DSCR8 | Down syndrome critical region gene 8 | NR_026838 | 9.23 |

| LOC648149 | Uncharacterized LOC648149 | AK123349 | 9.19 |

| GPR18 | G protein-coupled receptor 18 | NM_005292 | 9.14 |

| ORM1 | Orosomucoid 1 | NM_000607 | 9.04 |

| GATA3 | GATA binding protein 3 | NM_001002295 | 9.03 |

| KCNB1 | Potassium voltage-gated channel, Shab-related subfamily, member 1 | NM_004975 | 8.97 |

| OCA2 | Oculocutaneous albinism II | NM_000275 | 8.90 |

| PDZRN4 | PDZ domain containing ring finger 4 | NM_013377 | 8.86 |

To understand MSX1 actions in hDPSCs differentiating into osteoblasts, we performed a gene-set approach using the 2923 downregulated and 3480 upregulated genes. The WikiPathways analysis showed that the MSX1 knockdown downregulated various genes involved in focal adhesion, endochondral ossification, integrin-mediated cell adhesion, matrix metalloproteinases, calcium regulation, and insulin signaling (Table 4), whereas it upregulated genes involved in sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) signaling, cholesterol biosynthesis, adipogenesis, and fatty acid biosynthesis (Table 5). These findings revealed that MSX1 regulates various cellular processes in hDPSCs differentiating into osteoblasts.

Table 4.

The WikiPathways analysis selected gene sets significantly downregulated in MSX1-knockdown cells.

| Ranking | Pathway | P value | Gene counts (gene number of pathway) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Focal adhesion | 4.20E − 09 | 36 (188) |

| 2 | IL-4 signaling pathway | 2.55E − 05 | 13 (55) |

| 3 | Endochondral ossification | 6.27E − 05 | 14 (64) |

| 4 | Muscle cell tarbase | 7.95E − 05 | 41 (336) |

| 5 | Integrin-mediated cell adhesion | 8.22E − 05 | 18 (99) |

| 6 | Matrix metalloproteinases | 9.72E − 05 | 9 (31) |

| 7 | Regulation of toll-like receptor signaling pathway | 1.12E − 04 | 22 (150) |

| 8 | Calcium regulation in the cardiac cell | 1.30E − 04 | 23 (149) |

| 9 | MicroRNAs in cardiomyocyte hypertrophy | 3.35E − 04 | 15 (105) |

| 10 | Insulin signaling | 4.14E − 04 | 23 (161) |

Table 5.

The WikiPathways analysis selected gene sets significantly upregulated in MSX1 knockdown cells.

| Ranking | Pathway | P value | Gene counts (gene number of pathway) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SREBP signalling | <1.00E − 44 | 24 (50) |

| 2 | Lymphocyte tarbase | <1.00E − 44 | 78 (420) |

| 3 | Cholesterol biosynthesis | 1.86E − 17 | 16 (17) |

| 4 | Muscle cell tarbase | 1.78E − 10 | 65 (336) |

| 5 | Epithelium tarbase | 9.47E − 10 | 52 (278) |

| 6 | Folate metabolism | 1.47E − 09 | 22 (68) |

| 7 | Adipogenesis | 3.19E − 08 | 30 (131) |

| 8 | Leukocyte tarbase | 1.47E − 07 | 28 (128) |

| 9 | Fatty acid biosynthesis | 1.73E − 06 | 10 (22) |

| 10 | SREBF and miR33 in cholesterol and lipid homeostasis | 8.09E − 06 | 8 (18) |

3.4. MSX1 Knockdown Upregulates Cholesterol Synthesis-Related Genes

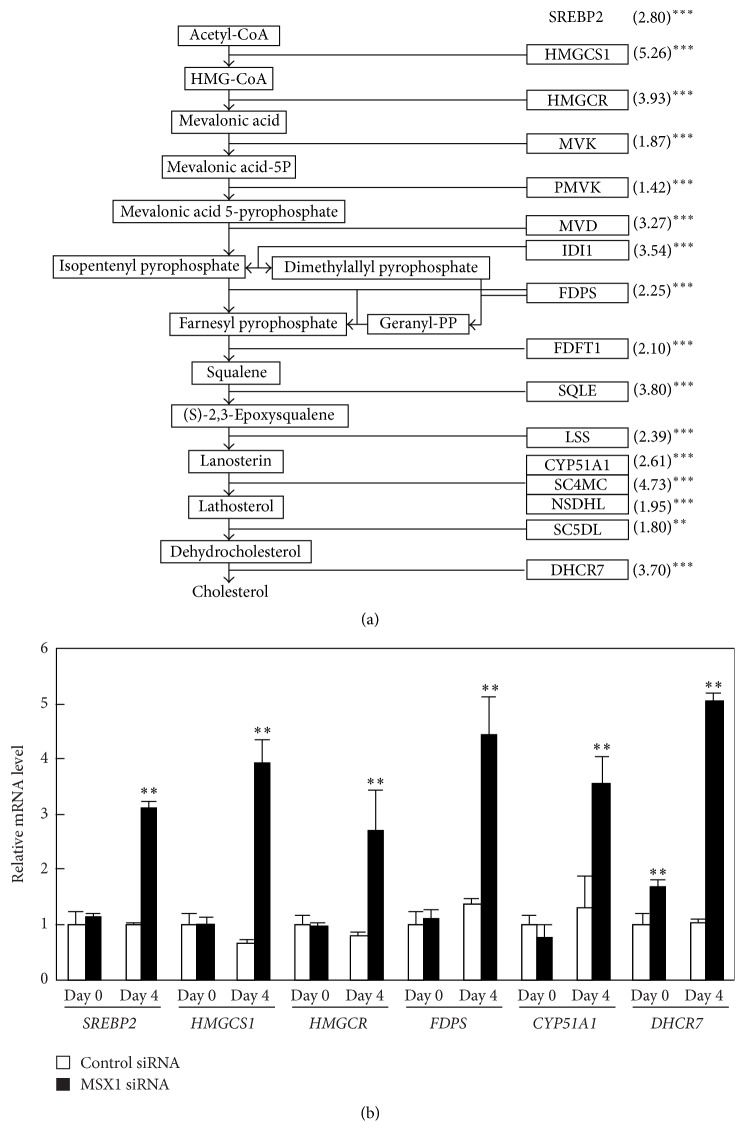

In MSX1-knockdown hDPSCs, “SREBP signaling” and “cholesterol biosynthesis” were the top 1st and 3rd upregulated gene sets, respectively (Table 5). The SREBP2 master transcriptional factor regulates the expression of all genes encoding enzymes in cholesterol synthesis pathway [25]. Because cholesterol synthesis is closely linked with osteoblast differentiation [17], we examined the effect of MSX1 knockdown on the expression of these genes. DNA microarray analyses showed that all cholesterol synthesis-related genes, including SREBP2, were significantly upregulated by MSX1 knockdown on day 4 (Figure 5(a)). Quantitative RT-PCR analyses confirmed that MSX1 knockdown increased SREBP2, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase 1 (HMGCS1), HMG-CoA reductase (HMGCR), farnesyl diphosphate synthase (FDPS), Cytochrome P450 Family 51 Subfamily A Polypeptide 1 (CYP51A1), and 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase (DHCR7) mRNA levels (Figure 5(b)).

Figure 5.

Effects of MSX1 knockdown on the expression of cholesterol synthesis-related genes, which are direct targets for SREBP2, in hDPSCs. (a) The cholesterol biosynthesis pathway is shown and the bold frames indicate target genes for the master transcriptional factor SREBP2. Microarray analysis indicates all genes involved in cholesterol synthesis are upregulated by MSX1 knockdown. The numbers in brackets represent the fold changes in gene expression in MSX1-knockdown cells as compared with the control cells. (b) The mRNA levels of genes relevant to cholesterol synthesis, including SREBP2, HMGCS1, HMGCR, FDPS, CYP51A1, and DHCR7, were quantified by RT-qPCR analysis. Values are averages ±SD for three cultures. ∗∗ P < 0.01; ∗∗∗ P < 0.001.

4. Discussion

Previous studies showed that mouse MSX1 was implicated in craniofacial bone development [1, 2, 4]. In mouse embryos, MSX1 suppresses precocious differentiation and calcification in dental mesenchymal cells and maintains these cells in a proliferative state to ensure subsequent craniofacial and tooth development [6, 26]. High levels of osteoblast number, cell proliferation, and apoptosis in MSX1 transgenic mice suggest that MSX1 modulates mouse craniofacial bone modeling [4]. However, the role of MSX1 in human cells remains poorly understood. In the present study, we demonstrated that MSX1 plays an essential role in osteogenic differentiation of hDPSCs.

In human DPSC cultures, MSX1 knockdown resulted in suppressed expression of RUNX2, ALPL, BMP2, and OCN. These results demonstrate that MSX1 modulated the major signaling/transcriptional pathways regulating hard tissue differentiation to enhance osteogenic potential of hDPSCs. However, MSX1 knockdown unexpectedly increased the mRNA level of OSX, another transcriptional factor involved in osteoblast maturation. This indicates MSX1 does not activate the entire osteogenesis program, perhaps because MSX1 cooperates with other transcription factors to fully control osteogenesis. MSX1 knockdown enhanced PPARγ expression under the osteogenesis-induced condition, suggesting that MSX1 negatively regulates adipogenic differentiation. MSX1 may direct hDPSCs into the osteoblast lineage by preventing them from differentiating into the adipogenic lineage. MSX1 knockdown also resulted in downregulation of various genes involved in focal adhesion, integrin-mediated cell adhesion, matrix metalloproteinases, calcium regulation, insulin signaling, and other processes. The extensive effect of MSX1 knockdown on the entire gene expression profile emphasizes a crucial role of MSX1 in hDPSCs undergoing differentiation into osteoblasts.

Bidirectional transcription of the Msx1 gene has been previously reported [27–29]. In embryonic and newborn mice, sense and antisense Msx1 transcripts are differently expressed during development. In 705IC5 mouse odontoblasts, overexpression of Msx1 antisense RNA decreased the expression of Msx1 sense transcript, whereas overexpression of Msx1 sense RNA increased Msx1 antisense transcript. Thus, expression of mouse Msx1 is controlled by the balance of the two transcripts. In our experiments, however, MSX1 antisense transcript was not detected during osteogenic differentiation of hDPSCs irrespective of siRNA knockdown of MSX1 (data not shown). The presence of MSX1 antisense transcript in humans has so far been reported only in the embryo. Therefore, Msx1 antisense RNA does not seem to be involved in the MSX1 expression in hDPSCs. Under these conditions, the expression of Msx1 sense transcripts was markedly depressed in hDPSCs after treatment with MSX1 siRNA, indicating that the knockdown experiments worked appropriately regardless of the presence or absence of the Msx1 antisense transcript.

MSX2, a paralog of MSX1, has been shown to enhance osteogenic differentiation of various mesenchymal cells, including C3H10T1/2 cells and aorta myofibroblasts [30–32]. MSX1 and MSX2 activate aortic adventitial osteoprogenitors via overlapping yet distinct mechanisms [33]. MSX2, unlike MSX1, enhances OSX expression without an increase in RUNX2 expression in aortic myofibroblasts [30], suggesting distinct actions of MSX1 and MSX2 in osteoblast differentiation.

The molecular mechanism by which MSX1 activates the differentiation program remains unclear. MSX1 regulates transcriptional activity of target genes either by directly binding to the specific DNA MSX1-binding motif (C/GTAATTG) or through interactions with other transcriptional regulators. Interestingly, MSX1 binds to various transcriptional regulators, including Sp1, Sp3, Dlx3, Dlx5, PAX3, PAX9, BarH-like homeobox 1/BARX1, and PIAS1 [34–37]. Depending on the partner in the complex, MSX1 activates or represses transcription in the MSX1-interacting network of transcription factors [26, 38]. Moreover, MSX1 modifies chromatin structure near target genes by histone methylation [35, 39]. The interactions of MSX1 with various transcriptional regulators may account for the extensive changes in the expression levels of many genes (~6400) by MSX1 knockdown.

Statins, drugs for hyperlipidemia, enhance osteogenic differentiation of various mesenchymal cells, including osteoblast precursor cells, mesenchymal stem cells, and DPSCs, by inhibiting the synthesis of farnesyl pyrophosphate, decreasing cellular cholesterol, and activating the Ras-PI3K-Akt/MAPK signaling pathway, thereby increasing the expression of BMP2 and RUNX2 [17], although the underlying mechanisms are still controversial. Statins also suppress osteoclast function and enhance mandibular bone formation in vivo [40]. Interestingly, a previous study showed that simvastatin induces odontoblast differentiation of hDPSCs in vitro and in vivo [22]. However, no studies have shown the involvement of transcription factor(s) in the control of cholesterol synthesis during osteoblast differentiation. Here we found for the first time that MSX1 suppresses the entire cholesterol synthesis pathway in osteoblast differentiating hDPSCs by repressing SREBP2 and other related genes. This suppression of cholesterol synthesis may facilitate osteoblast differentiation. It is also interesting to note that various mutations in the cholesterol synthesis pathway, including 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase (DHCR7), cause craniofacial anomalies including cleft palate, suggesting the role of cholesterol synthesis in craniofacial development [41].

In conclusion, here we revealed for the first time that MSX1 is indispensable for osteoblast-like differentiation and calcification in hDPSCs derived from deciduous teeth. Furthermore, MSX1 was found to modulate a wide variety of genes, including cholesterol synthesis-related genes, during osteogenic differentiation of hDPSCs. We have not examined the effects of MSX1 siRNA in definitive teeth, although MSX1 may also function as a positive regulator of osteogenesis in definitive teeth as MSX1 mRNA levels are high in both definitive and deciduous teeth [15]. Our findings will provide new insights into the role of MSX1 in development and repair of teeth and may be useful in DPSC-based regenerative therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Exploratory Research (no. 24659876), Scientific Research (C; no. 25462889), and Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B; no. 15K20592) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan to Yukio Kato, Katsumi Fujimoto, and Noriko Goto, respectively. The authors would like to thank Dr. Eiso Hiyama at the Natural Science Center for Basic Research and Development and Hiroshima University for use of the equipment.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Satokata I., Maas R. Msx1 deficient mice exhibit cleft palate and abnormalities of craniofacial and tooth development. Nature Genetics. 1994;6(4):348–356. doi: 10.1038/ng0494-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maas R., Chen Y. P., Bei M., Woo I., Satokata I. The role of Msx genes in mammalian development. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1996;785:171–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb56256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orestes-Cardoso S. M., Nefussi J. R., Hotton D., et al. Postnatal Msx1 expression pattern in craniofacial, axial, and appendicular skeleton of transgenic mice from the first week until the second year. Developmental Dynamics. 2001;221(1):1–13. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nassif A., Senussi I., Meary F., et al. Msx1 role in craniofacial bone morphogenesis. Bone. 2014;66:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackenzie A., Leeming G. L., Jowett A. K., Ferguson M. W. J., Sharpe P. T. The homeobox gene Hox 7.1 has specific regional and temporal expression patterns during early murine craniofacial embryogenesis, especially tooth development in vivo and in vitro. Development. 1991;111(2):269–285. doi: 10.1242/dev.111.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han J., Ito Y., Yeo J. Y., Sucov H. M., Maas R., Chai Y. Cranial neural crest-derived mesenchymal proliferation is regulated by Msx1-mediated p19INK4d expression during odontogenesis. Developmental Biology. 2003;261(1):183–196. doi: 10.1016/S0012-1606(03)00300-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Y., Bei M., Woo I., Satokata I., Maas R. Msx1 controls inductive signaling in mammalian tooth morphogenesis. Development. 1996;122(10):3035–3044. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vieux-Rochas M., Bouhali K., Mantero S., et al. BMP-mediated functional cooperation between Dlx5;Dlx6 and Msx1;Msx2 during mammalian limb development. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051700.e51700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vastardis H., Karimbux N., Guthua S. W., Seidman J. G., Seidman C. E. A human MSX1 homeodomain missense mutation causes selective tooth agenesis. Nature Genetics. 1996;13(4):417–421. doi: 10.1038/ng0896-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamaguchi S., Machida J., Kamamoto M., et al. Characterization of novel MSX1 mutations identified in Japanese patients with nonsyndromic tooth agenesis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8, article e102944) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakatsuka R., Nozaki T., Uemura Y., et al. 5-Aza-2'-deoxycytidine treatment induces skeletal myogenic differentiation of mouse dental pulp stem cells. Archives of Oral Biology. 2010;55(5):350–357. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ranganathan K., Lakshminarayanan V. Stem cells of the dental pulp. Indian Journal of Dental Research. 2012;23(4, article 558) doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.104977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iohara K., Imabayashi K., Ishizaka R., et al. Complete pulp regeneration after pulpectomy by transplantation of CD105+ stem cells with stromal cell-derived factor-1. Tissue Engineering Part A. 2011;17(15-16):1911–1920. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakai K., Yamamoto A., Matsubara K., et al. Human dental pulp-derived stem cells promote locomotor recovery after complete transection of the rat spinal cord by multiple neuro-regenerative mechanisms. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2012;122(1):80–90. doi: 10.1172/JCI59251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujii S., Fujimoto K., Goto N., et al. Characteristic expression of MSX1, MSX2, TBX2 and ENTPD1 in dental pulp cells. Biomedical Reports. 2015;3(4):566–572. doi: 10.3892/br.2015.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li X., Cui Q., Kao C., Wang G.-J., Balian G. Lovastatin inhibits adipogenic and stimulates osteogenic differentiation by suppressing PPARγ2 and increasing Cbfa1/Runx2 expression in bone marrow mesenchymal cell cultures. Bone. 2003;33(4):652–659. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00239-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruan F., Zheng Q., Wang J. Mechanisms of bone anabolism regulated by statins. Bioscience Reports. 2012;32(6):511–519. doi: 10.1042/BSR20110118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu C., Wu Z., Sun H.-C. The effect of simvastatin on mRNA expression of transforming growth factor-beta1, bone morphogenetic protein-2 and vascular endothelial growth factor in tooth extraction socket. International Journal of Oral Science. 2009;1(2):90–98. doi: 10.4248/ijos.08011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ayukawa Y., Yasukawa E., Moriyama Y., et al. Local application of statin promotes bone repair through the suppression of osteoclasts and the enhancement of osteoblasts at bone-healing sites in rats. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontology. 2009;107(3):336–342. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pradeep A. R., Thorat M. S. Clinical effect of subgingivally delivered simvastatin in the treatment of patients with chronic periodontitis: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Periodontology. 2010;81(2):214–222. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee C.-T., Lee Y.-T., Ng H.-Y., et al. Lack of modulatory effect of simvastatin on indoxyl sulfate-induced activation of cultured endothelial cells. Life Sciences. 2012;90(1-2):47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okamoto Y., Sonoyama W., Ono M., et al. Simvastatin induces the odontogenic differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Endodontics. 2009;35(3):367–372. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gronthos S., Mankani M., Brahim J., Robey P. G., Shi S. Postnatal human dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) in vitro and in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(25):13625–13630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240309797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karamzadeh R., Eslaminejad M. B., Aflatoonian R. Isolation, characterization and comparative differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells derived from permanent teeth by using two different methods. Journal of Visualized Experiments. 2012;(69) doi: 10.3791/4372.4372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horton J. D., Goldstein J. L., Brown M. S. SREBPs: activators of the complete program of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in the liver. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2002;109(9):1125–1131. doi: 10.1172/jci200215593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng X.-Y., Zhao Y.-M., Wang W.-J., Ge L.-H. Msx1 regulates proliferation and differentiation of mouse dental mesenchymal cells in culture. European Journal of Oral Sciences. 2013;121(5):412–420. doi: 10.1111/eos.12078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blin-Wakkach C., Lezot F., Ghoul-Mazgar S., et al. Endogenous Msx1 antisense transcript: in vivo and in vitro evidences, structure, and potential involvement in skeleton development in mammals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(13):7336–7341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131497098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coudert A. E., Pibouin L., Vi-Fane B., et al. Expression and regulation of the Msx1 natural antisense transcript during development. Nucleic Acids Research. 2005;33(16):5208–5218. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petit S., Meary F., Pibouin L., et al. Autoregulatory loop of Msx1 expression involving its antisense transcripts. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2009;220(2):303–310. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng S.-L., Shao J.-S., Charlton-Kachigian N., Loewy A. P., Towler D. A. MSX2 promotes osteogenesis and suppresses adipogenic differentiation of multipotent mesenchymal progenitors. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(46):45969–45977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m306972200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ichida F., Nishimura R., Hata K., et al. Reciprocal roles of Msx2 in regulation of osteoblast and adipocyte differentiation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(32):34015–34022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m403621200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ishii M., Merrill A. E., Chan Y.-S., et al. Msx2 and Twist cooperatively control the development of the neural crest-derived skeletogenic mesenchyme of the murine skull vault. Development. 2003;130(24):6131–6142. doi: 10.1242/dev.00793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng S.-L., Behrmann A., Shao J.-S., et al. Targeted reduction of vascular Msx1 and Msx2 mitigates arteriosclerotic calcification and aortic stiffness in LDLR-deficient mice fed diabetogenic diets. Diabetes. 2014;63(12):4326–4337. doi: 10.2337/db14-0326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Catron K. M., Zhang H., Marshall S. C., Inostroza J. A., Wilson J. M., Abate C. Transcriptional repression by Msx-1 does not require homeodomain DNA-binding sites. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1995;15(2):861–871. doi: 10.1128/MCB.15.2.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee H., Habas R., Abate-Shen C. Msx1 cooperates with histone H1b for inhibition of transcription and myogenesis. Science. 2004;304(5677):1675–1678. doi: 10.1126/science.1098096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang J., Abate-Shen C. The Msx1 homeoprotein recruits G9a methyltransferase to repressed target genes in myoblast cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5, article e37647) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 37.Zhang H., Hu G., Wang H., et al. Heterodimerization of Msx and Dlx homeoproteins results in functional antagonism. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1997;17(5):2920–2932. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao M., Gupta V., Raj L., Roussel M., Bei M. A network of transcription factors operates during early tooth morphogenesis. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2013;33(16):3099–3112. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01597-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang J., Kumar R. M., Biggs V. J., et al. The Msx1 homeoprotein recruits polycomb to the nuclear periphery during development. Developmental Cell. 2011;21(3):575–588. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee Y., Schmid M. J., Marx D. B., et al. The effect of local simvastatin delivery strategies on mandibular bone formation in vivo. Biomaterials. 2008;29(12):1940–1949. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.12.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wassif C. A., Zhu P., Kratz L., et al. Biochemical, phenotypic and neurophysiological characterization of a genetic mouse model of RSH/Smith—Lemli—Opitz syndrome. Human Molecular Genetics. 2001;10(6):555–564. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.6.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]