Abstract

Objective

In 2011, the YMCA of the USA adopted Healthy Eating (HE) Standards for all their afterschool programs (ASPs). The extent to which YMCA-ASPs comply with the standards is unknown.

Methods

Twenty ASPs from all YMCA-ASPs across SC (N=102) were invited to participate. Direct observation of the foods/beverages served and staff behaviors were collected on four non-consecutive days/ASP.

Results

One ASP did not serve a snack. Of the remaining, a total of 26% ASPs served a fruit/vegetable and 32% served water every day; 26% served sugar-sweetened beverages, 47% served sugar-added foods, and only 11% served whole grains, when grains were served. Staff were sitting with the children (65%) or verbally promoting healthy eating (15%) on at least one observation day. Staff where drinking non-approved drinks (25%) or foods (45%) on at least one observation day. No ASPs served snacks family-style every day.

Conclusions/Implications

Additional efforts are required to assist YMCA-operated ASPs in achieving these important nutrition standards.

Introduction

In November 2011 the YMCA of the USA adopted the Healthy Eating (HE) Standards for their afterschool programs (ASPs) that called on all YMCA-operated ASPs to serve a fruit or vegetable and water every day, to serve whole grains when serving grains, to eliminate sugar-sweetened beverages and foods, to serve snacks family style, and for staff to role model healthy eating behaviors.15 These standards have the potential to make an important public health impact as it relates to improving the quality of the foods and beverages served as snack to the tens-of-thousands of children who attend the thousands of YMCA-operated ASPs across the country every day of the school year.4,5

The adoption of the HE Standards represented an important and necessary change to the types of foods and beverages typically served in ASPs, which predominately included foods high in salt or sugar, and were almost entirely void of whole grains, fruits or vegetables.4,5 The national adoption of the HE Standards represents a unique opportunity to evaluate how the voluntary adoption of policy at an organizational level can translate into changes in routine practice.15 Previous studies on the adoption of healthy eating policies have indicated that, when coupled with additional professional development training components, improvements in the quality of the foods and beverages served can be made in ASPs.8,9,13 For the YMCA nationally, there is limited information regarding the impact of the HE Standards on what is served for snack in their ASPs. Such information is useful when determining the extent to which the adoption of the policy is altering routine practice of ASPs, and when determining topics for professional development for ASP providers. Thus, the purpose was to evaluate the extent to which YMCA operated ASPs were meeting the HE Standards four years (spring 2015) after the standards were adopted nationally in one southeastern state.

Methods

Sampling Strategy for Evaluation of ASPs

A total of 21 YMCA Associations operate independently across South Carolina (SC). One Association did not operate an ASP, and therefore, was not included in the sampling strategy. The remaining 20 Associations collectively operated 102 programs with a median of 4 programs per association (range of 1–13 programs operated by a single Association). Based on fall 2014 enrollment, these programs enrolled 5,244 children ages 5 to 12 years for the 2014–15 academic school year. Across all 20 Associations, programs were operated in YMCA facilities (25%), schools (64%), churches (3%), and community locations (8%). For the purpose of this study no programs were selected that operated in churches or in community locations (in this sample, “community” referred to programs operating within apartment complexes), given the low number of programs within these settings.

The sampling strategy included a single program from each of the 20 Associations. This was deliberate given differences in organizational structure and capacity across the Associations, the need to ensure representativeness of ASPs dispersed geographically throughout the state, and to include all YMCA partner Associations. Next, to ensure sufficient sample size at the child level and representativeness of programs of all sizes, programs were first grouped by Association, and second, stratified by enrollment. For Associations that operated a single program (n = 5), that program was selected. For Associations that operated two or more programs (n = 15), the following sampling strategy was employed. For Associations where all programs enrolled fewer than 50 children (n = 3), the largest program was selected. For Associations that operated programs with more than 50 children enrolled (n = 12), a single program was randomly selected from these. A single ASP in one Association did not serve snacks; rather children brought snacks from home. For this reason, this ASP was not included in foods and beverages served analyses, but was included in the staff behaviors analyses. All methods were approved by the Institution Review Board of the University of South Carolina.

Measures

Measurements occurred during the spring of 2015 (March–April). Consistent with established protocols, each ASP was visited for data collection on 4 non-consecutive, unannounced days Monday through Thursday.1–3,6,17 Evaluation of the YMCA Healthy Eating Standards was operationalized as the following: programs, on each day of operation, will serve 1) a fruit or vegetable, and 2) water, and each day the program will not serve 3) sugar-sweetened candy, desserts (e.g., cookies, toaster pastries) or beverages (e.g., chocolate milk, powdered drink mixes); and 4) when serving grains, will serve whole grains determined by the first word on the ingredient list containing the word “whole” in front of the grain. Food preparation and storage amenities were collected via self-report from the ASP site leaders. Each site leader was asked to indicate what access the program had to locations where they could store foods and beverages (e.g., refrigerator, pantry) and wash and prepare foods (e.g., sinks not located in bathrooms, kitchens).

Snack Classification

The primary outcome for this study were the types of foods and beverages ASPs served for snack. The types of foods and beverages served as snack were recorded via direct observation by trained research personnel. Immediately at the start of snack, the trained observer recorded the brand name(s), size, and packaging, where appropriate, of the foods and beverages served as snack for that day. Foods and beverage items served as snacks were classified according to existing categories for snacks and beverages:4,12,17 sugar-sweetened beverages (e.g., soda, powered drink mixed, sport drinks); dairy food (e.g., string cheese, yogurt); milk unsweetened (non-fat, 1%, 2%, and whole); milk sweetened (e.g., chocolate, strawberry); 100% fruit juice; salty flavored snacks (e.g., Doritos, Chex Mix), salty unflavored snacks (e.g., pretzels, plain corn tortilla chips); desserts (e.g., cookies, pop tarts); candy (e.g., chocolate, frozen treats); non-fruit fruit (e.g., fruit roll ups; fruit leather); prepackaged fruit (e.g., applesauce, fruit in syrup); cereal sugar-sweetened (e.g., Fruit Loops); cereal unsweetened (e.g., Cheerios); and fruits and vegetables (e.g., fresh, frozen, dried) recorded separately. Water was recorded if programs provided water in cups or bottles during snack time. Grain products were classified as whole grains if the ingredients list on the package indicated that the first ingredient contained the word “whole” in front of the grain. This definition is consistent with the exact policy language in the HE Standards.

Family Style

Family style serving was defined as children serve themselves from common bowls and pitchers with limited help from adults. This definition is taken directly from the HE Standards of the YMCA of the USA.

Healthy Eating Behaviors of Staff

The System for Observing Staff Promotion of Physical Activity and Nutrition (SOSPAN), a systematic observation instrument,16 was used to track staff healthy eating behaviors. Trained observers completed all observations. Observers completed classroom training, video analysis, and field practice prior to data collection. Classroom training lasted 3hrs and included a review of study protocol, orientation to the instrument, and committing observational codes to memory. Video analysis included watching video clips from ASPs and rating those clips using SOSPAN protocols. Field practice/reliability scans were completed on at least six days. Inter-observer agreement criteria was set at >80% using interval-by-interval agreement for each category, and, consistent with published reliability protocols, reliability was collected prior to measurement and on at least 30% of data collection days.14 Inter-observer reliability for the ASP context and staff behaviors were estimated via interval-by-interval percent agreement and weighted kappa (κw). Percent agreement ranged from 92.9% to 100% and κw ranged from 0.46 to 0.93. Reliability was checked weekly to identify disagreements. Operational definitions of variables with borderline or low reliability (<90% agreement) were then discussed with observers to ensure reliability and prevent observer drift.

On observation days, observers systematically rotated through areas that were occupied by children and staff from the beginning to the end of the afterschool program. Five scans were completed in each occupied area prior to moving to the next area. Scans were also completed from the beginning to the end of each snack period. This procedure allowed for observers to capture a representative sample of all staff healthy eating behaviors that occurred during (e.g., eating provided snack with children) and outside (e.g., drinking a soda during an enrichment time) of snack time. Staff use of nutrition education materials, such as curricula, coloring sheets, enrichment activities (e.g., taste tests) were captured during program operating hours.

Comparison of Estimates to Previous Studies

As a secondary comparison, the foods and beverages served across the sample of 20 YMCA operated ASPs were compared to previously published studies that reported either foods and/or beverages served in ASPs.5,7,9,10,13 For intervention studies, only the baseline data were used for comparison which represents routine practice in ASPs.

Statistical Analyses

For the purpose of this study, descriptive statistics were used to calculate the number of ASPs achieving the HE Standards overall and for each individual standard, separately. The outcomes for foods and beverages served and staff behaviors were expressed as a percentage of days an item or behavior was observed across the 4 days of measure, with a possible range of 0% (never served/observed) to 100% (served/observed every day). A program was only classified as compliant (i.e., achieving an HE Standard) if they either served a compliant item each day of measure (i.e., fruits or vegetables observed 4 out of 4 days) or if a non-compliant item was never served (e.g., never observing a sugar-sweetened beverage, 0 out of 4 days). To evaluate the whole grain standard, only ASPs that served a grain (which is optional) were classified as whether the grain served was whole or non-whole grain. For staff behaviors, percentages were calculated identical to that of the foods and beverages, where a program was classified as meeting a standard (e.g., never observing a behavior, such as staff never observed eating unhealthy foods in front of children) or not compliant (e.g., staff not sitting with children during snack on 2 of the 4 days of measure). All descriptive statistics were calculated using Stata (v.14, College Station, TX). Where possible, the comparison between the estimates of foods and beverages observed in the current sample of 19 YMCA operated ASPs and those from previously published studies was made via Hedge’s g with the sample size representing the number of ASPs in the respective study. These estimates were calculated using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (v.2.2.064, Englewood, NJ).

Results

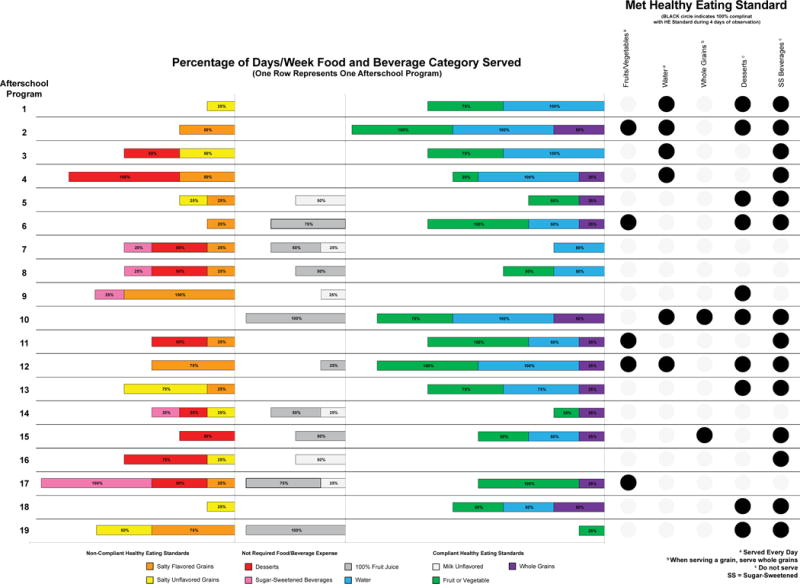

The descriptive characteristics of the sample of 19 ASPs are presented in Table 1. The percentage of days a food and beverage item was observed across each of the 19 ASPs and whether an ASP achieved a given HE Standard are presented in Figure 1. Overall, 5 of the 19 ASPs served a fruit or vegetable every day, 6 ASPs served water every day, 2 of 17 ASPs served whole grains when serving a grain, 5 ASPs did not serve any SSBs, and 9 ASPs did not serve any sugar-sweetened foods. Only 3 ASPs did not meet any of the 5 HE Standards for foods and beverages, while the remaining 16 ASPs met anywhere from 1 to 4 HE Standards. No programs met all 5 HE Standards.

Table 1.

Evaluation and non-evaluation YMCA operated afterschool program characteristics

| Evaluation Sites (n = 20)

|

Non-Evaluation Sites (n = 71)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | |

|

|

||||||

| Number of Children Enrolled (average per ASP) | 70 | ±39 | (15, 155) | 48 | ±41 | (5, 248) |

| Less than 50 | 35% | 68% | ||||

| 50 to 75 | 25% | 20% | ||||

| 76 to 100 | 20% | 3% | ||||

| 101 to 125 | 10% | 3% | ||||

| 126 to 150 | 5% | 6% | ||||

| More than 150 | 5% | 1% | ||||

| Total Children Served | 1,408 | 3,836 | ||||

| Number of Staff (average per ASP) | 7 | ±5 | (2, 18) | 4 | ±3 | (1, 16) |

| Households in Poverty (percent) | 13% | ±6 | (4.3%, 22.2%) | 14% | ±6% | (2.9%, 31.4%) |

| Age Range (years) a | 7.6 | ±1.7 | (5, 12) | (5, 12) | ||

| Percent Girls a | 44% | |||||

| Serve a Snack (percent of ASPs) | 95% | 99% | ||||

| Receive State of Federal Reimbursement for Snack | 35% | 61% | ||||

| Serve a Hot Meal (percent of ASPs) | 10% | 7% | ||||

| Receive State of Federal Reimbursement for Meal | 10% | 7% | ||||

| Food Preparation and Storage (n) | ||||||

| Refrigerator and freezer combination unit | 10 | |||||

| Standalone freezer | 2 | |||||

| Pantry or storage closet for dry goods | 12 | |||||

| Portable cooler/ice chest | 11 | |||||

| Kitchen | 4 | |||||

| Food preparation sink that is not in a bathroom | 12 | |||||

| Stove/oven | 2 | |||||

| Microwave | 12 | |||||

| Serving plates or bowls | 10 | |||||

| Location | ||||||

| YMCA | 44% | 20% | ||||

| School | 56% | 66% | ||||

| Other | 0% | 13% | ||||

| Revenue (US$) | ||||||

| Total Operating Revenue | $5,303,181 | |||||

| Percent Revenue from Child Care | 14.6% | |||||

Figure 1. Percentage of the four days of direct observation a food and beverage were served across 19 of 20 YMCA operated afterschool programs.

Note: A single program did not serve snacks and is not represented in the Figure.

Comparison between the snacks served in the current study to those reported in the previous studies are presented in Table 2. A total of 5 previously published studies5,8–10,13 on ASP snacks were identified. The ASPs in the current study were serving fruits/vegetables at a greater number of days compared to studies of both YMCA and non-YMCA ASPs (2.8 days per week versus range of 0.1 to 1.9 days per week). A single study reported whole grains, with the estimate of 0.2 days per week compared to 0.9 days per week in the current sample. Programs in the current sample served desserts 1.8 days per week versus 1.3 to 2.9 days per week reported in previous studies. Also, programs in the current sample served SSBs the same amount or on fewer days per week (0.5 days per week) compared to other studies (0.4 to 2.4 days per week). Finally, programs in the current sample served water on a slightly greater number of days (2.5 days per week) compared to other studies (1.9 to 2.1 days per week). All other estimates and corresponding effect sizes can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of foods and beverages served as snack between the current sample of programs and previously published estimates

| Study | Current Study

|

Mozaffarian et al.

|

Beets et al.

|

Beets et al.

|

Coleman et al.

|

Cassidy et al.

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organization(s) | YMCA | YMCA | YMCA | Non-YMCA | Non-YMCA | Non-YMCA | ||||||||||||||

| Number of ASPs | 20 | 7 | 4 | 20 | 7 | NA | ||||||||||||||

| Year Data Collected | 2015 | 2005–2006 | 2011 | 2013 | 2005–2006 | 2001 | ||||||||||||||

| Measure | Direct Observation | Menu Analysis | Direct Observation | Direct Observation | Direct Observation | Menu Analysis | ||||||||||||||

|

|

Baseline

|

Baseline

|

Control - Baseline

|

Intervention - Baseline

|

Baseline

|

Baseline Menu

|

||||||||||||||

| M | (SD) | M | (SD) | ES | (95%CI) | M | (SD) | ES | (95%CI) | M | (SD) | ES | (95%CI) | M | (SD) | ES | (95%CI) | M | No. days in 5d Menu | |

| Foods | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Fruits | 2.5 | (2.5) | ||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Vegetables | 0.8 | (1.8) | ||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Total Fruits/Vegetables | 2.8 | (2.5) | 1.9 | (2.2) | 0.36 | (−0.5, 1.2) | 0.1 | (0.5) | 1.12 | (0.04, 2.20) | 0.7 | (1.8) | 0.89 | (0.1, 1.7) | 0.6 | (1.6) | 0.95 | (0.2, 1.7) | 0.1 | 1.0 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Dips | 0.8 | (1.8) | ||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Dairy | 1.1 | (2.1) | ||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Salty Snacks – Flavored | 1.6 | (2.3) | 2.1 | (2.1) | 3.1 | (1.6) | 1.6 | (2.4) | 2.7 | (2.5) | 4.0 | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Salty Snacks – Unflavored | 1.0 | (2.0) | 0.6 | (1.7) | 2.0 | (2.5) | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Whole Grains | 0.9 | (2.0) | 0.2 | (0.2) | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Desserts | 1.8 | (2.4) | 1.3 | (1.0) | 0.23 | (−0.6, 1.1) | 2.0 | (1.4) | 0.08 | (−0.95, 1.12) | 2.6 | (2.5) | 0.32 | (−0.4, 1.1) | 2.9 | (2.5) | 0.44 | (−0.3, 1.2) | 1.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Cereal – Sugar-Sweetened | 0.1 | (0.8) | ||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Cereal – Unsweetened | 0.1 | (0.6) | ||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Beverages | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugar-Sweetened non-Dairy Beverages | 0.1 | (0.6) | ||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Milk – Sugar-Sweetened | 0.5 | (1.5) | 0.5 | (1.6) | 0.0 | (0.0) | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Total Sugar-Sweetened Beverages | 0.5 | (1.6) | 0.4 | (0.9) | 0.07 | (−0.8, 0.9) | 1.7 | (2.0) | 0.70 | (−0.36, 1.75) | 1.5 | (2.3) | 0.51 | (−0.2, 1.3) | 2.4 | (2.5) | 0.37 | (−0.4, 1.1) | ||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| 100% Fruit Juice | 0.8 | (1.8) | 3.2 | (2.4) | 1.6 | (2.4) | 0.3 | (1.2) | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Milk – Unflavored | 1.3 | (2.2) | 1.2 | (2.1) | 0.7 | (1.7) | 0.9 | (2.0) | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | 2.5 | (2.5) | 1.9 | (2.7) | 0.23 | (−0.6, 1.1) | 2.1 | (2.5) | 0.17 | (−0.6, 0.9) | 2.0 | (2.5) | 0.19 | (−0.5, 0.9) | ||||||

Note: Blank cells represent the study did not report the food or beverage.

The compliance of staff with the environmental Healthy Eating Standards is presented in Table 3. Overall, very few ASPs met the environmental HE Standards including having staff that were verbally promoting healthy eating (3 out of 20 ASPs this was observed on at least one day), having staff delivering some form of healthy eating education (3 out of 20 ASPs), and serving snack family style (5 out of 19 ASPs). Staff were observed eating or drinking non-compliant items during the program in 13 and 11 ASPs, respectively. Compliance with the HE Standards for staff behaviors ranged from a low of only a single program with 100% compliance for staff verbally promoting healthy eating every day, sitting with children during snack every day, and delivering healthy eating education every day, to 5, 9, and 18 programs where staff were never observed drinking or eating inappropriate items or children were observed accessing the vending machines, respectively. No programs were observed serving snack family style every day.

Table 3.

Compliance with Staff and Environmental Context standards from the Healthy Eating Standards.

| Healthy Eating Staff/Environment Standard | Percentage of Days Overall (N = 80) | Number of ASPs where behavior was observed on at least one day | Number of ASPs 100% Compliant |

|---|---|---|---|

| Days staff verbally promote healthy eating | 9% | 3 | 1 |

| Days staff sit with children during snack | 27% | 13 | 1 |

| Days staff eat inappropriate foods | 18% | 11 | 9b |

| Days staff drink inappropriate beverages | 32% | 15 | 5b |

| Days staff deliver healthy eating education | 8% | 3 | 1 |

| Days children buy from vending | 6% | 2 | 18b |

| Days snacks served family style a | 10% | 5 | 0 |

Healthy Eating Standard “family style” was evaluated in only 19 programs where snack was served and 76 days of observation

Number of programs where staff/child behaviors were never observed (100% compliance)

Conclusions

This study evaluated compliance to the HE Standards in a sample of YMCA-operated ASPs in one southeastern state. Overall, compliance to the HE Standards varied considerably between the observed programs. However, the estimates of foods and beverages served in the current sample of ASPs are similar to or higher than those previously reported. While encouraging, there were a number of programs who were complaint with some HE Standards, yet were non-compliant with others. The data collected herein suggest that the HE Standards are only being adhered to partially and relatively poorly in the environmental category. Most importantly, these results suggest that improvements in one standard does not necessarily lead to compliance with other standards. For instance some programs served a fruit or vegetable alongside sugar sweetened beverages every day. Thus, although the HE Standards have been officially adopted for over four years, additional assistance is required to help practitioners fully achieve.

Although our data suggest compliance with some of the HE Standards, no ASP was fully compliant across all of the standards. This suggests, at minimum, improvements have occurred since the 2011 adoption of the standards in terms of the types of foods and beverages served as snack. This is evident in the comparison to previously published studies5,8–10,13 on foods and beverages served in ASPs which shows the current sample of YMCA operated ASPs were serving fruits and vegetables on more days per week compared to what has been previously reported during routine practice (i.e., before an intervention) in either YMCA operated or non-YMCA-operated ASPs. This finding is encouraging and indicates that the adoption of policy at an organizational level can lead to meaningful and potentially impactful changes in routine practice.

Four years after the national adoption of the HE Standards, the lack of 100% compliance regarding foods and beverages, along with the limited compliance with those standards targeting staff behaviors, indicates policy alone may be insufficient to achieve full compliance. Although YMCA-operated ASPs have access to other supports through online content and resources, in addition to opportunities to take part in face-to-face professional development trainings, it appears – at least within the confines of the current sample – additional supports beyond what is currently available are needed to fully achieve the HE Standards. Previous studies5,8,11,13 have utilized learning collaboratives or a capacity building approach and have substantially increased compliance towards the HE Standards, yet neither approach fully attained the HE Standards. Efforts like these should be considered for YMCA-operated ASPs to further their progress towards meeting the standards. However, these efforts will require an additional investment to deliver trainings to thousands of ASPs across the nation and will also require new models for implementation and dissemination to ensure effectiveness.

There are a number of strengths to the current study. These include the sampling design, objective measure of foods, beverages, and staff behaviors, and the wide range of programs with varying characteristics, such as enrollment size and location of operation. There are, however, several limitations. These include programs only operating within a single southeastern state and, therefore, these programs may not be representative of YMCA-operated ASPs across the nation. Second, despite the stratified sampling design, a limited number of programs were sampled; and, therefore, drawing conclusions to the single state as a whole should be done with caution. However, the ASPs included in this study were similar in their program-level characteristics as to the non-sampled ASPs and thus should closely represent current practice related to snacks in YMCA operated ASPs (see Table 1).

In conclusion, YMCA operated ASPs were compliant with some, but not all, of the HE Standards adopted in 2011. Studies are required to identify and test the implementation and dissemination of existing and new strategies designed to assist ASPs improve the nutritional quality of the foods and beverages served.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute Of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HD079422. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Beets MW, Beighle A, Bottai M, Rooney L, Tilley F. Pedometer-determined step count guidelines for afterschool programs. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2012;9(1):71–77. doi: 10.1123/jpah.9.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beets MW, Huberty J, Beighle A. Physical Activity of Children Attending Afterschool Programs Research- and Practice-Based Implications. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(2):180–184. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beets MW, Rooney L, Tilley F, Beighle A, Webster C. Evaluation of policies to promote physical activity in afterschool programs: are we meeting current benchmarks? Prev Med. 2010;51(3–4):299–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beets MW, Tilley F, Kim Y, Webster C. Nutritional policies and standards for snacks served in after-school programmes: a review. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(10):1882–1890. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011001145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beets MW, Tilley F, Weaver RG, Turner-McGrievy G, Moore JB, Webster C. From policy to practice: addressing snack quality, consumption, and price in after-school programs. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2014;46(5):384–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beets MW, Weaver RG, Moore JB, Turner-McGrievy G, Pate RR, Webster C, et al. From Policy to Practice: Strategies to Meet Physical Activity Standards in YMCA Afterschool Programs. Am J Prev Med. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.012. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beets MW, Weaver RG, Tilley F, Turner-McGrievy G, Huberty J, Ward DS, et al. Salty or Sweet? Nutritional Quality, Consumption, and Cost of Snacks Served in Afterschool Programs. The Journal of school health. 2015;85(2):118–24. doi: 10.1111/josh.12224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beets MW, Weaver RG, Turner-McGrievy G, Huberty J, Ward DS, Freedman D, et al. Making Healthy Eating Policy Practice: A Group Randomized Controlled Trial on Changes in Snack Quality, Costs, and Consumption in After-School Programs. American journal of health promotion: AJHP. 2015 doi: 10.4278/ajhp.141001-QUAN-486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cassady D, Vogt R, Oto-Kent D, Mosley R, Lincoln R. The power of policy: a case study of healthy eating among children. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(9):1570–1. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.072124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coleman KJ, Geller KS, Rosenkranz RR, Dzewaltowski DA. Physical activity and healthy eating in the after-school environment. J Sch Health. 2008;78(12):633–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giles CM, Kenney EL, Gotrtmaker SL, Lee RM, Thayer JC, Mont-Ferguson H, et al. Increasing water availability during afterschool snack: Evidence, strategies, and partnerships from a group randomized trial. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(3S2):S136–S142. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mozaffarian RS, Wiecha JL, Roth BA, Nelson TF, Lee RM, Gortmaker SL. Impact of an Organizational Intervention Designed to Improve Snack and Beverage Quality in YMCA After-School Programs. Am J Public Health. 2009 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.158907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mozaffarian RS, Wiecha JL, Roth BA, Nelson TF, Lee RM, Gortmaker SL. Impact of an Organizational Intervention Designed to Improve Snack and Beverage Quality in YMCA After-School Programs. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(5):925–932. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.158907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ridgers ND, Stratton G, McKenzie T. Reliability and Validity of the system for observing children’s activity and relationships during play (SOCARP) J Phys Act Health. 2010;7:17–25. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vinluan MH, Hofman J. Transforming out-of-school time environments: the Y’s commitment to healthy eating and physical activity standards. Am J Health Promot. 2014;28(3 Suppl):S116–8. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.28.3s.S116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weaver RG, Beets MW, Webster C, Huberty J. System for Observing Staff Promotion of Activity and Nutrition (SOSPAN) Journal of physical activity & health. 2014;11(1):173–185. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2012-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weaver RG, Hutto B, Saunders R, Moore JB, Turner-McGrievy G, Huberty J, et al. Making Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Policy Practice: Process evaluation of a group randomized controlled intervention targeting healthy eating and physical activity in afterschool programs. Health Education Research. 2015;30(6):849–865. doi: 10.1093/her/cyv052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]