Abstract

Purpose

Diet, physical activity, and smoking cessation are modifiable lifestyle factors that have been shown to improve health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in many cancer survivors. Our objective was to systematically review the literature on the associations between lifestyle factors, namely diet, physical activity, smoking status, and HRQOL in bladder cancer survivors.

Methods

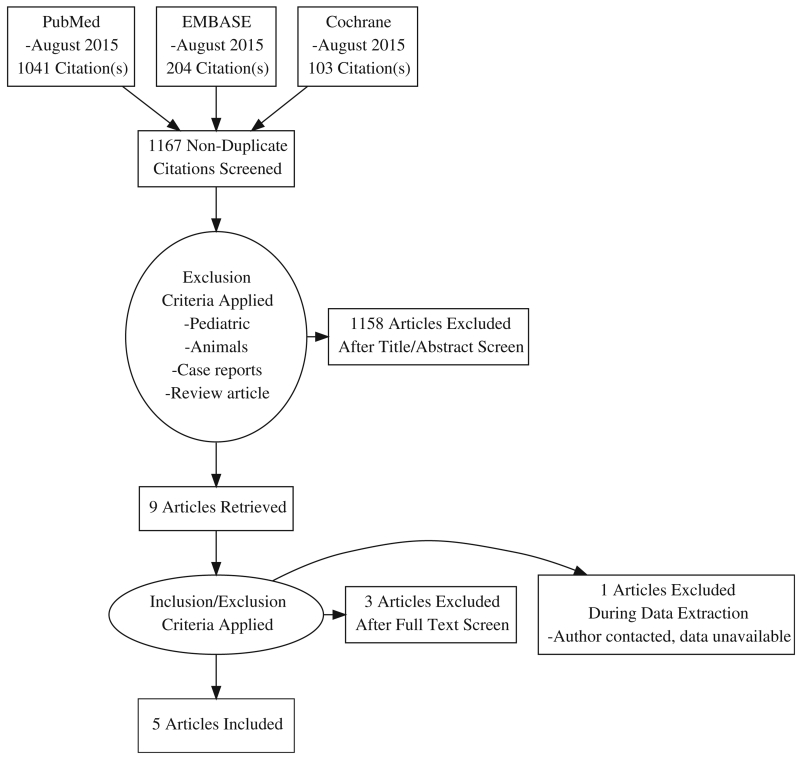

We queried PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane libraries. Two reviewers reviewed abstracts independently, and a third reviewer arbitrated disagreements. A descriptive analysis was performed. Quality assessment was conducted using the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for observational studies and the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for clinical trials.

Results

We identified 1167 publications in the initial search, of which 9 met inclusion criteria for full-text review. We were able to obtain data on the outcomes of interest for 5 publications. A total of 1288 patients who underwent treatment for bladder cancer were included. Three studies were observational by design and two were randomized controlled trials. Physical activity was addressed by 4 studies, smoking status by 2 studies, and diet by 1 study.

Conclusions

The review highlights the limited evidence around lifestyle factors and quality of life in bladder cancer survivors. There is some evidence for a positive association between HRQOL and physical activity, but insufficient evidence upon which to draw conclusions about the effects of consuming fruits and vegetables or non-smoking.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

There is limited evidence to support a positive association between health-related quality of life and physical activity, but insufficient evidence upon which to base any conclusions about consumption of fruits and vegetables or smoking cessation in bladder cancer survivors.

Keywords: Bladder cancer, Urothelial carcinoma, Lifestyle factors, Exercise, Diet, Smoking, Quality of life

Introduction

Bladder cancer is the fifth most common cancer in the USA, with a projected 74,000 new cases to be diagnosed in 2015 [1]. Two broad clinical phenotypes of bladder cancer exist: non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC, stages Ta, T1, and Tis) and muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC, stages T2, T3, and T4) and each is managed differently. An important feature of NMIBC is its high recurrence rate, which necessitates frequent surveillance and instrumentation, resulting in potential for diminished quality of life [2]. In MIBC, the risk of metastasis is dramatically higher than in NMIBC, resulting in need for more invasive potentially curative treatment, including radical surgery, radiation, and/or systemic chemotherapy. These therapies, however, also carry significant risk of treatment-related loss of quality of life [3].

Diet, physical activity, and smoking cessation are modifiable lifestyle factors that have been shown to significantly improve health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and survivorship in a variety of cancer patients [4]. They form crucial aspects of tertiary prevention among cancer survivors, and there are established guidelines on diet and physical activity recommendations for cancer survivors [5].

The relationship between modifiable lifestyle factors and risk for bladder cancer has been explored,[6, 7], with evidence suggesting that physical activity is associated with a decreased risk for bladder cancer, and obesity with an increased risk. However, there is currently no consensus on the associations between lifestyle factors and HRQOL in bladder cancer survivors. The objective of this study was to systematically review the literature to explore the relationship between HRQOL, dietary patterns, physical activity, and smoking status in bladder cancer survivors.

Methods

Protocol registration and search strategy

The systematic review was registered with the PROSPERO database (CRD42015026079) and was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. An information specialist queried PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane libraries through August 2015. The search strings can be found in Appendix.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) adult patients with diagnosis of bladder cancer; (2) assessment of at least one of (i) diet, (ii) physical activity and/or exercise, and (iii) smoking status; and (3) analysis of the relationship between one of these lifestyle factors and HRQOL as measured by a validated instrument. Studies were excluded if they involved: pediatric patients, animals, case reports, or review papers. Duplicate publications were also excluded.

Manuscript screening and data abstraction

Two reviewers independently evaluated abstracts based on inclusion/exclusion criteria with a third reviewer arbitrated any disagreements. The full texts for all eligible abstracts were acquired and reviewed. One author was contacted for clarification of data. Data were extracted and stored in an electronic database. The data that were abstracted included: author, article title, journal name, year of publication, country of origin, study design, sample size, mean age, gender distribution, quality of life instrument used, whether physical activity was examined, physical activity instrument, the HRQOL-physical quality relationship, whether diet was examined, the diet instrument, the HRQOL-diet relationship, whether smoking status was included, the smoking status instrument, and the HRQOL-smoking status relationship.

Statistical analysis

As there were only two randomized controlled trials (RCTs), a descriptive analysis was performed for these studies. To allow for comparisons between studies using different HRQOL measurement tools and varying sample sizes, we calculated a Cohen’s d (d = [mean1 − mean2]/SDpooled) when possible. The standardized mean differences were defined as small (d = 0–0.35), medium (d = 0.35–0.65), or large (d>0.65) [8]. The Cohen’s d values were not pooled due to the lack of consistency in HRQOL indices reported across the few studies for each lifestyle factor.

Quality assessment

Study quality assessment was conducted by two reviewers using the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for observational studies and the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for clinical trials. The Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale is used to evaluate studies based on three criteria: (1) patient selection, (2) comparability of groups, and (3) ascertainment of outcome. Studies are assessed on a star scoring scale, with higher scores given for higher quality studies. The quality assessment of the observational studies can be found in Supplemental Table 1. The Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool is used to assign a “risk” category (low or high) for multiple types of biases common in clinical trials. The quality assessment of the clinical trials can be found in Supplemental Table 2. Studies were not excluded in the review based on the perceived quality of the study.

Results

Search results

We identified 1167 publications in the initial search, of which 9 met inclusion criteria for full-text review. Of these, we were able to obtain data on the outcomes of interest for 5 publications. The PRISMA diagram for the study selection process is shown in Fig. 1. A total of 1288 patients who underwent treatment for bladder cancer were included. Three studies were observational by design, and the remaining two were randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The quality of life measures used included the EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (QLQ-C30), the RAND-36 Health Status Inventory, the SF-36, and the FACT-Bl. The characteristics of these questionnaires are summarized in Table 1. Characteristics of the 5 included studies can be found in Table 2.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram for the study selection process

Table 1.

Questionnaire characteristics

| Questionnaire | Scaling |

|---|---|

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | Global health scale |

| Functional scales | |

| Physical | |

| Emotional | |

| Role | |

| Cognitive | |

| Social functioning | |

| Symptom scales | |

| Fatigue | |

| Pain | |

| Nausea/vomiting | |

| Single-item scales | |

| Dyspnea | |

| Insomnia | |

| Appetite loss | |

| Constipation | |

| Diarrhea | |

| Financial difficulties | |

| FACT-Bl | Global health scales |

| FACT-Bl | |

| FACT-General | |

| Trial outcome index (TOI) | |

| Subscales | |

| Physical well-being (PWB) | |

| Functional well-being (FWB) | |

| Emotional well-being (EWB) | |

| Social well-being (SWB) | |

| Additional concerns | |

| Urinary function | |

| Bowel function | |

| Sexual function | |

| Body image | |

| Weight/loss appetite | |

| Ostomy issues | |

| SF-36 | General health score |

| Subscales | |

| Vitality | |

| Physical functioning | |

| Bodily pain | |

| General health perceptions | |

| Physical role functioning | |

| Emotional role functioning | |

| Social role functioning | |

| Mental health | |

| RAND-36 Health Status Inventory | Global health composite score |

| Physical domains | |

| Physical functioning | |

| Role-physical | |

| Bodily pain | |

| General health | |

| Mental domains | |

| Vitality | |

| Social functioning | |

| Role-emotional | |

| Mental health |

Table 2.

Study characteristics

| Reference | Design | No. of subjects |

HRQOL measure(s) |

PA measure(s) | Dietary measure(s) | Smoking measure(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blanchard CM et al. (2008) [9] |

Cross-sectional survey |

586 | RAND-36 Health Status Inventory |

Godin Leisure- Time Exercise Questionnaire |

Self-reported response to question, “How many days per week do you eat at least 5 servings of fruits and vegetables a day?” |

Self-reported yes/ no question: “Do you currently smoke cigarettes on a regular basis?” |

| Porserud A et al. (2014) [10] |

Randomized controlled trial |

18 | SF-36 | 6MWT, figure of eight, steps outside, 30-s chair stand test |

NA | NA |

| Karvinen KH et al. (2007) [11] |

Cross-sectional survey |

525 | FACT-Bl | Godin Leisure- Time Exercise Questionnaire |

NA | NA |

| Jensen BT et al. (2007) [12] |

Randomized controlled trial |

50 | EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (QLQ-C30) |

Exercise intervention including prehab and post- operative rehab |

NA | NA |

| Kowalkowski MA etal. (2014) [13] |

Cross-sectional survey |

109 | EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (QLQ-C30), Bladder Cancer – Superficial – 24 (BLS-24) and multiple psychosocial items. |

NA | NA | Interview |

Physical activity and exercise

Four studies included an analysis of the association between physical activity or exercise and HRQOL. Of these, two were cross-sectional surveys [9, 11] and two were randomized control trials [10, 12]. Both cross-sectional surveys used the Godin Leisure-Time Questionnaire to measure self-reported physical activity. Blanchard et al. found a small-medium effect for physical activity such that HRQOL scores among subjects reporting more physical activity were significantly higher than those reporting lower levels of activity [9]. Similarly, Karvinen et al. also reported a positive, dose-dependent relationship, with a small-medium effect size, between exercise and HRQOL [11]. These findings are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Associations between lifestyle factors and HRQOL

| Study | HRQOL measure | HRQOL scale/subscale(s) | d PA a | d Diet b | d Smoking c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blanchard et al. [9] | RAND-36 Health Status Inventory | General health score | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Karvinen KH et al. [11] | FACT-Bl | FACT-Bl | 0.4 | – | – |

| FACT-G | 0.3 | – | – | ||

| TOI | 0.4 | – | – | ||

| PWB | 0.2 | – | – | ||

| FWB | 0.3 | – | – | ||

| EWB | 0.1 | – | – | ||

| SWB | 0.2 | – | – | ||

| Additional concerns | 0.3 | – | – | ||

| Kowalkowski MA et al. [13] | EORTC BLS-24 and multiple psychosocial items. |

Psychological distress (Brief Symptom Index) | – | – | 0.5 |

| Traumatic stress (Impact of Events Scale) | – | – | 0.5 | ||

| Fear of recurrence (CaPSURE) | – | – | 0.6 | ||

| Social constraint (Lepore) | – | – | 0.7 | ||

| Social support (REACH) | – | – | 0.2 | ||

| Illness intrusiveness | – | – | 0.4 | ||

| Urinary symptoms (EORTC BLS-24) | – | – | 0.3 | ||

| Impact of repeated treatments (EORTC BLS-24) | – | – | 0.7 | ||

| Future perspective (EORTC BLS-24) | – | – | 0.3 |

FACT-BI Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Bladder Cancer, FACT-G Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General, TOI Trial Outcome Index, PWB Physical Well Being, FWB Functional Well Being, EWB Emotional Well Being, SWB Social Well Being

Cohen’s d for physical activity

Cohen’s d for diet

Cohen’s d for smoking; d values are interpreted as small (d = 0–0.35), medium (d = 0.35–0.65), or large (d>0.65)

Porserud et al. and Jensen et al. both conducted RCTs comparing an exercise intervention group to a sedentary control group [10, 12]. There was a trend toward improvement in particular quality of life domains in the study by Porserud et al. (Table 4). However, these differences were very small and only the improvement in the role physical domain reached statistical significance. Jensen et al. described a medium-sized difference (10.5 points) in role function on the EORTC QLQ-C30 in the physical activity intervention group, but this failed to reach statistical significance [10, 12]. Neither study noted significant differences in global health scores. It should also be noted that the majority of patients in the study by Porserud et al. were unable to complete the exercise program [10].

Table 4.

HRQOL changes after physical activity intervention

| Reference | No. of subjects | Physical activity intervention | HRQOL measure |

Subscales | Mean difference |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porserud A et al. [10] |

18 | 6MWT, figure of eight, steps outside, 30-s chair stand test |

SF-36a | General health | 8.0 | 0.508 |

| Physical functioning | 5.5 | 0.504 | ||||

| Role physical | 52.5 | 0.031 | ||||

| Bodily pain | 2.9 | 1.000 | ||||

| Vitality | 6.0 | 0.766 | ||||

| Social functioning | 19.7 | 0.150 | ||||

| Role emotional | 25 | 0.389 | ||||

| Mental health | −5.3 | 0.339 | ||||

| Physical health score | 5.7 | 0.079 | ||||

| Mental health score | 3.5 | 1.000 | ||||

| Jensen et al.[12] | 50 | Prehab (exercise-based prehabilitation program), including step training on a step trainer (15 min per training session). Postop rehab (Physical therapy twice per day for the first 7 postoperative days). |

EORTC QLQ-C30b | Global health status | −2.4 | 0.60 |

| Physical functioning | −2.4 | 0.59 | ||||

| Role functioning | −10.5 | 0.11 | ||||

| Emotional functioning | −4.2 | 0.35 | ||||

| Cognitive functioning | −6.1 | 0.37 | ||||

| Social functioning | −1.4 | 0.93 |

All scales are scored on a scale of 0–100. The study did not list a minimum clinically important difference. Follow-up was at 14 weeks

Per the study, a difference of less than 4 points is considered “trivial”, 4–9 points is considered “small”, 9–15 points is considered “medium”, and>15 P is considered “large.” Follow-up was at 4 months

Diet

Only one study, by Blanchard et al., examined the relationship between dietary patterns and HRQOL (Table 3) [9]. Specifically, Blanchard et al. queried subjects about fruits and vegetable consumption by asking survivors to choose a number between 0 and 7 in response to the question, “How many days per week do you eat at least 5 servings of fruits and vegetables a day?” There was no association between fruit and vegetable consumption and HRQOL among respondents (Table 3).

Smoking status

Two studies, by Blanchard et al. and Kowalkowski et al., offered data regarding the association between smoking status and HRQOL (Table 3) [9, 13]. Blanchard et al. found that HRQOL was not associated with smoking status. In contrast, Kowalkowski et al. reported higher psychological distress (d = 0.5), traumatic stress (d = 0.5), fear of recurrence (d = 0.6), social constraint (d = 0.7), illness intrusiveness (d = 0.4), and impact of repeated treatments (d = 0.7) among current smokers compared with non-smokers. However, there was no reported relationship between overall HRQOL and smoking status.

Discussion

We found that physical activity was associated with improved HRQOL, particularly in observational studies. However, differences in HRQOL between exercise intervention and control groups in RCTs were generally small and were largely not statistically significant. Fruit and vegetable consumption and smoking status were not associated with overall quality of life, though non-smokers did have improved scores in some measures of QOL. However, due to the very limited number of studies on diet and smoking in our review, there is insufficient evidence upon which to draw any conclusions about the strength or direction of associations between them and HRQOL. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first systematic review of the associations between lifestyle factors and HRQOL in bladder cancer survivors. The results suggest a dearth of evidence regarding this topic.

Survivors of multiple other cancers who meet physical activity recommendations, eat healthy diets, maintain a normal BMI, and are non-smokers also tend to have a better HRQOL, suggesting that the relationship between lifestyle factors and HRQOL may transcend cancer type [14–16]. Though our review did not assess percentage of survivors meeting recommendations as an endpoint, studies in other cancers seem to suggest that many, if not the majority, of cancer survivors are not meeting ACS guidelines regarding lifestyle factors [14, 16]. Given the importance of HRQOL in cancer survivorship, further research is necessary to better evaluate longitudinal, causal relationships between lifestyle factors and HRQOL in bladder cancer survivors. We also found that there is much heterogeneity between the different HRQOL indices, making comparisons across studies somewhat difficult. We attempted to overcome the discrepancy between studies by using Cohen’s d to compare effect sizes. A more standardized HRQOL scale in future studies may allow for more direct comparability.

During cancer treatment, many survivors become deconditioned and can develop impaired cardiovascular fitness because of the direct and secondary effects of therapy [17]. Randomized trials in other cancer sites have shown that exercise training is safe, tolerable, and effective for most survivors. Structured aerobic and resistance training programs after treatment can improve cardiovascular fitness and strength and can have positive effects on balance, body composition, and quality of life [18, 19]. Both the observational studies and randomized trials in bladder cancer in this review produced similar results. The benefits of an improved lifestyle may extend beyond HRQOL. Although there is insufficient evidence in bladder cancer, there are observational studies in multiple solid tumor types showing that physical activity is linked to decreased cancer recurrence and increased survival [20]. All survivors are encouraged to avoid a sedentary lifestyle and engage in daily physical activity. Both the American Cancer Society (ACS) and the ACSM have made physical activity recommendations for cancer survivors [21].

An extensive body of literature regarding diet exists in the setting of bladder cancer prevention, but little evidence has been collected among the survivors. However, evidence from other tumors, particularly breast and prostate cancer, suggests that diet has an important role following diagnosis and treatment. Weight gain after cancer diagnosis and treatment is common in other tumors, and being overweight can exacerbate a survivor’s risk for functional decline, comorbidity, cancer recurrence or death, and can reduce quality of life [22]. Small reductions in weight among overweight or obese survivors or small increases in physical activity among sedentary individuals are thought to yield meaningful improvements in cancer-specific outcomes and overall health [23]. In fact, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recently released a position statement on the link between obesity and cancer, encouraging oncologists to use a cancer diagnosis as a “teachable moment” to counsel patients on the benefits of improving diet and on the adverse impact of a poor diet on prognosis, drug delivery, morbidity, and risk of second malignancies [24]. Data suggest that healthy dietary patterns (as characterized by plant-based diets that have ample amounts of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, with limited quantities of red and processed meats, refined grains, and sugars) are associated with a decrease in cancer recurrence and improved outcomes in survivors [21].

Though our review did not demonstrate a significant difference in overall HRQOL between smokers and non-smokers and limited benefit in certain aspects, smoking cessation is likely still be of benefit in bladder cancer survivors, as there is a growing body of evidence that shows smoking is associated with increased risk of recurrence and progression [25].

Conclusions

There is some evidence for a positive association between HRQOL and physical activity, but insufficient evidence upon which to draw any conclusions about the effects of consuming fruits and vegetables or non-smoking in bladder cancer survivors. Future research should focus on larger trials of the effect of lifestyle interventions on quality of life in this group of survivors. There is also a need for standardization of quality of life metrics for improved comparison.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Duke-CTSA Grant Number 5TL1TR001116-03. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Appendix

Table 5.

Search strings in PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane libraries

| PubMed | ||

| Search | Query | Items found |

| #1 | Search “Urinary Bladder Neoplasms”[Mesh] OR (urothelial carcinoma*[tiab] OR urothelial neoplasm*[tiab] OR urothelial malignanc*[tiab] OR “urothelial cancer”[tiab] OR urothelial tumor*[tiab] OR urothelial tumour*[tiab]) OR (urinary carcinoma*[tiab] OR urinary neoplasm*[tiab] OR urinary malignanc*[tiab] OR “urinary cancer”[tiab] OR urinary tumor*[tiab] OR urinary tumour*[tiab]) OR (bladder carcinoma*[tiab] OR bladder neoplasm*[tiab] OR bladder malignanc*[tiab] OR “bladder cancer”[tiab] OR bladder tumor*[tiab] OR bladder tumour*[tiab]) OR (“Carcinoma, Transitional Cell”[Mesh] OR transitional cell carcinoma*[tiab] OR transitional cell neoplasm*[tiab] OR transitional cell malignanc*[tiab] OR “transitional cell cancer”[tiab] OR transitional cell tumor*[tiab] OR transitional cell tumour*[tiab]) OR (“pelvic tumor”[tiab] OR “pelvic tumour”[tiab] OR “pelvic tumors”[tiab] OR “pelvic tumours”[tiab] OR “Pelvic Neoplasms”[Mesh] OR pelvic malignanc*[tiab] OR pelvic neoplasm*[tiab] OR “pelvic cancer”[tiab] OR “pelvic carcinoma”[tiab]) OR “MIBC”[tiab] OR “NIMBC”[tiab] |

67207 |

| #2 | Search “quality of life”[MeSH Terms] OR “quality of life” [tiab] OR “QOL”[tiab] OR “HRQOL”[tiab] OR “well being” [tiab] OR “well-being” [tiab] OR “wellbeing”[tiab] | 254826 |

| #3 | Search #1 AND #2 | 1156 |

| #4 | Search #3 NOT (“Case Reports” [Publication Type] OR “a case report”[ti] OR “: case report”[ti]) | 1050 |

| #5 | Search #4 NOT (“Animals”[Mesh] NOT “Humans”[Mesh]) | 1041 |

| EMBASE | ||

| #1 | ‘bladder tumor’/exp OR ‘transitional cell carcinoma’/exp OR ‘urothelial carcinoma’:ti,ab OR ‘urothelial carcinomas’:ti,ab OR ‘urothelial neoplasm’:ti,ab OR ‘urothelial neoplasms’:ti,ab OR ‘uro tlielial malignancy’:ti,ab OR ‘urothelial malignancies’:ti,ab OR ‘urothelial cancer’:ti,ab OR ‘urothelial tumor’:ti,ab OR ‘urothelial tumors’:ti,ab OR ‘urothelial tumour’:ti,ab OR ‘urothelial tumours’:ti,ab OR ‘urinary carcinoma’:ti,ab OR ‘urinary carcinomas’:ti,ab OR ‘urinary neoplasm’:ti,ab OR ‘urinary neoplasms’:ti,ab OR ‘urinary malignancy’:ti,ab OR ‘urinary malignancies’:ti ,ab OR ‘urinary cancer’:ti,ab OR ‘urinary tumor’:ti,ab OR ‘urinary tumour’:ti,ab OR ‘urinary tumors’:ti,ab OR ‘urinary tumours’:ti,ab OR ‘bladder carcinoma’:ti,ab OR ‘bladder carcinomas’:ti,ab OR ‘bladder neoplasm’:ti,ab OR ‘bladder neoplasms’:ti,ab OR ‘bladder malignancy’:ti,ab OR ‘bladder malignancies’:ti,ab OR ‘bladder cancer’:ti,ab OR ‘bladder tumor’:ti,ab OR ‘bladder tumour’:ti,ab OR ‘bladder tumors’:ti,ab OR ‘bladder tumours’:ti,ab OR ‘transitional cell carcinoma’:ti,ab ‘transitional cell carcinomas’:ti,ab OR ‘transitional cell neoplasm’:ti,ab OR ‘transitional cell neoplasms’:ti,ab OR ‘transitional cell malignancy’:ti,ab OR ‘transitional cell malignancies’:ti,ab OR ‘transitional cell cancer’:ti,ab OR ‘transitional cell tumor’:ti,ab OR ‘transitional cell tumour’:ti,ab OR ‘transitional cell tumors’:ti,ab OR ‘transitional cell tumours’:ti,ab OR ‘pelvic tumor’:ti,ab OR ‘pelvic tumour’:ti,ab OR ‘pelvic tumors’:ti,ab OR ‘pelvic tumours’:ti,ab OR ‘pelvic malignancy’:ti,ab OR ‘pelvic malignancies’:ti,ab OR ‘pelvic neoplasm’:ti,ab OR ‘pelvic neoplasms’:ti,ab OR ‘pelvic cancer’:ti,ab OR ‘pelvic carcinoma’:ti,ab OR ‘pelvic carcinomas’:ti,ab OR ‘MIBC’:ti,ab OR ‘NIMBC’:ti,ab |

7079 |

| #2 | ‘quality of lite’/exp OR ‘wellbeing’/exp OR ‘quality of life’:ab,ti OR ‘qol’:ab,ti OR lrrqol’:ab,ti OR ‘well being’:ab,ti OR ‘well-being’:ab,ti OR ‘wellbeing’:ab,ti | 422153 |

| #3 | #1 AND #2 | 257 |

| #4 | #3 AND [humans]/lim | 220 |

| #5 | ‘case report’/exp OR ‘a case report’:ti OR ‘: case report’:ti | 2069466 |

| #6 | #4 NOT #5 | 204 |

| Cochrane | ||

| ID | Search | Hits |

| #1 | urothelial carcinoma or “urothelial carcinomas” or “urothelial neoplasm” or “urothelial neoplasms” or “urothelial malignancy” or “urothelial malignancies” or “urothelial cancer” or “urothelial tumor” or “urothelial tumors” or “urothelial tumour” or “urothelial tumours” or “urinary carcinoma” or “urinary carcinomas” or “urinary neoplasm” or “urinary neoplasms” or “urinary malignancy” or “urinary malignancies” or “urinary cancer” or “urinary tumor” or “urinary tumour” or “urinary tumors” or “urinary tumours” or “bladder carcinoma” or “bladder carcinomas” or “bladder neoplasm” or “bladder neoplasms” or “bladder malignancy” or “bladder malignancies” or “bladder cancer” or “bladder tumor” or “bladder tumour” or “bladder tumors” or “bladder tumours” or “transitional cell carcinoma” “transitional cell carcinomas” or “transitional cell neoplasm” or “transitional cell neoplasms” or “transitional cell malignancy” or “transitional cell malignancies” or “transitional cell cancer” or “transitional cell tumor” or “transitional cell tumour” or “transitional cell tumors” or “transitional cell tumours” or “pelvic tumor” or “pelvic tumour” or “pelvic tumors” or “pelvic tumours” or “pelvic malignancy” or “pelvic malignancies” or “pelvic neoplasm” or “pelvic neoplasms” or “pelvic cancer” or “pelvic carcinoma” or “pelvic carcinomas” or “MIBC” or “NIMBC”:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) |

2213 |

| #2 | quality of lite or “wellbeing” or “qol” or “hrqol” or “well being” or “well-being”:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) | 41155 |

| #3 | #1 and #2 | 103 |

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11764-016-0533-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Conflict of Interest Ajay Gopalakrishna declares that he has no conflict of interest. Thomas Longo declares that he has no conflict of interest. Joseph Fantony declares that he has no conflict of interest. Megan Van Noord declares that she has no conflict of interest. Brant Inman declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical approval This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA: Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson DC, Greene PS, Nielsen ME. Surgical advances in bladder cancer: at what cost? Urologic Clin N Am. 2015;42:235–52. ix. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scarpato KR, Morgans AK, Moses KA. Optimal management of muscle-invasive bladder cancer—a review. Res Rep Urol. 2015;7:143–51. doi: 10.2147/RRU.S73566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demark-Wahnefried W, Jones LW. Promoting a healthy lifestyle among cancer survivors. Hematol/Oncol Clin N Am. 2008;22:319–42. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demark-Wahnefried W, Rogers LQ, Alfano CM, Thomson CA, Courneya KS, Meyerhardt JA, et al. Practical clinical interventions for diet, physical activity, and weight control in cancer survivors. CA: Cancer J Clin. 2015 doi: 10.3322/caac.21265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keimling M, Behrens G, Schmid D, Jochem C, Leitzmann MF. The association between physical activity and bladder cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:1862–70. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noguchi JL, Liss MA, Parsons JK. Obesity physical activity and bladder cancer. Curr Urol Rep. 2015;16:546. doi: 10.1007/s11934-015-0546-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanchard CM, Courneya KS, Stein K. Cancer survivors’ adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health-related quality of life: results from the American Cancer Society’s SCS-II. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2198–204. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.6217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Porserud A, Sherif A, Tollback A. The effects of a physical exercise programme after radical cystectomy for urinary bladder cancer. A pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2014;28:451–9. doi: 10.1177/0269215513506230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karvinen KH, Courneya KS, North S, Venner P. Associations between exercise and quality of life in bladder cancer survivors: a population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev: Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res Cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol. 2007;16:984–90. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jensen BT, Jensen JB, Laustsen S, Petersen AK, Sondergaard I, Borre M. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation can impact on health-related quality of life outcome in radical cystectomy: secondary reported outcome of a randomized controlled trial. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2014;7:301–11. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S62172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kowalkowski MA, Goltz HH, Petersen NJ, Amiel GE, Lerner SP, Latini DM. Educational opportunities in bladder cancer: increasing cystoscopic adherence and the availability of smoking-cessation programs. J Cancer Educ: Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 2014;29:739–45. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0649-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mosher CE, Sloane R, Morey MC, Snyder DC, Cohen HJ, Miller PE, et al. Associations between lifestyle factors and quality of life among older long-term breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer. 2009;115:4001–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schlesinger S, Walter J, Hampe J, von Schonfels W, Hinz S, Kuchler T, et al. Lifestyle factors and health-related quality of life in colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer Causes Control: CCC. 2014;25:99–110. doi: 10.1007/s10552-013-0313-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spector DJ, Noonan D, Mayer DK, Benecha H, Zimmerman S, Smith SK. Are lifestyle behavioral factors associated with health-related quality of life in long-term survivors of non-Hodgkin lymphoma? Cancer. 2015;121:3343–51. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lakoski SG, Eves ND, Douglas PS, Jones LW. Exercise rehabilitation in patients with cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:288–96. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown JC, Huedo-Medina TB, Pescatello LS, Pescatello SM, Ferrer RA, Johnson BT. Efficacy of exercise interventions in modulating cancer-related fatigue among adult cancer survivors: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev: Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res Cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol. 2011;20:123–33. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mishra SI, Scherer RW, Geigle PM, Berlanstein DR, Topaloglu O, Gotay CC, et al. Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for cancer survivors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:Cd007566. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007566.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ballard-Barbash R, Friedenreich CM, Courneya KS, Siddiqi SM, McTiernan A, Alfano CM. Physical activity, biomarkers, and disease outcomes in cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:815–40. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Meyerhardt J, Courneya KS, Schwartz AL, et al. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA: Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:243–74. doi: 10.3322/caac.21142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen X, Lu W, Gu K, Chen Z, Zheng Y, Zheng W, et al. Weight change and its correlates among breast cancer survivors. Nutr Cancer. 2011;63:538–48. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2011.539316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hudis CA, Jones L. Promoting exercise after a cancer diagnosis: easier said than done. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:829–30. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ligibel JA, Alfano CM, Courneya KS, Demark-Wahnefried W, Burger RA, Chlebowski RT, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology position statement on obesity and cancer. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3568–74. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simonis K, Shariat SF, Rink M. Smoking and smoking cessation effects on oncological outcomes in nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. Curr Opin Urol. 2014;24:492–9. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0000000000000079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.