Abstract

Extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor (E-EWS/pPNET) is a rare aggressive malignant small round cell tumor. In this report, we present the case of a 15-year-old boy who suffered from acute abdominal pain accompanied by hematemesis and melena, and was eventually diagnosed with E-EWS/pPNET. To date, there have been only five reported cases of E-EWS/pPNET of the small bowel including the patient in this report. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first documentation of a pPNET of the small bowel mesentery at nonage. All these have made this report rare and significant.

Keywords: Extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma, Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor, Nonage, Small bowel mesentery, Spontaneous rupture

Core tip: Extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumors (E-EWS/pPNETs) are rare aggressive malignant small round cell tumors that are derived from the outer central and autonomic nervous systems. To date, there have been only five reported cases of E-EWS/pPNET of the small bowel including the patient presented in this report. The patient presented in this report is the youngest and had the worst prognosis.

INTRODUCTION

Extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor (E-EWS/pPNET) of the small bowel is an extremely rare soft tissue neoplasm that tends to strike children and young adults[1-4]. It is a highly malignant small round cell tumor that has been thought to be of neural crest origin. It is known that primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNET) show bidirectional or multidirectional differentiation[5]. In this report, we present a young patient who had a gigantic abdominal tumor, which is a condition commonly misdiagnosed; and describe the specific clinical manifestations associated with his condition.

CASE REPORT

A 15-year-old boy was transferred to our emergency unit from his local hospital due to acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage. He suffered from acute abdominal pain, accompanied by hematemesis and melena. At the time of admission, the patient denied having any symptoms before the current episode of bleeding. We initially postulated that his bleeding was more likely due to duodenal ulcer bleeding. He was given blood and fresh frozen plasma transfusions. Abdominal enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed a large ovoid solid and cystic tumor (20 cm × 20 cm × 10 cm), which was observed at the left upper quadrant, with a rupture within the mass (Figure 1). It was discovered that there was a translocation of the peripheral organ and vasculature under pressure. During emergency surgery, a giant mass was noted in the jejunal mesenteric region, which was located 15 cm from the ligament of Treitz. The tumor involved the full-thickness of the jejunal wall and was closely associated with the left ureter, kidney, psoas major and spleen. Resection of the tumor and partial resection of the small intestine were performed. Macroscopically, the size of the tumor was 20 cm × 20 cm × 10 cm (Figure 2). An incision on the surface of the tumor revealed sclerotic tissue and bleeding regions inside the tumor. The tumor had infiltrated the full-thickness wall of the jejunum (Figure 3). Small round cells containing uniform vesicular and Homer-Wright rosettes were found microscopically (Figure 4). Erythrocytes were also found between tumor cells (Figure 5). Postoperative laboratory examination revealed that the patient’s serum levels of carcinoembryonic antigen, CA19-9, CA12-5 and CA15-3 were normal. When examined by immunohistochemistry, the excised tumor cells stained positive for CD99, vimentin, synaptophysin, CD56 and NSE, while they were negative for CK20, CD3, chromogranin-A and S-100. Postoperatively, the patient received systemic chemotherapy. However, the patient died of intra-abdominal recurrence three months later.

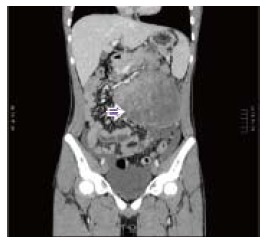

Figure 1.

Computerized tomography scan revealing a large ovoid solid and cystic tumor (17 cm × 15 cm × 10 cm) at the left upper quadrant (right arrow).

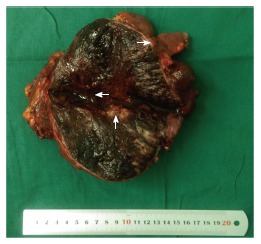

Figure 2.

Macroscopically, a large ovoid solid and cystic tumor (20 cm × 20 cm × 10 cm) was observed at the left upper quadrant, and the tumor infiltrated the full-thickness wall of the jejunum (left arrow).

Figure 3.

Macroscopically, an incision into the surface of the tumor revealed sclerotic tissue (up arrow) and bleeding regions inside the tumor (left arrow). The tumor had infiltrated the full-thickness wall of the jejunum (right arrow).

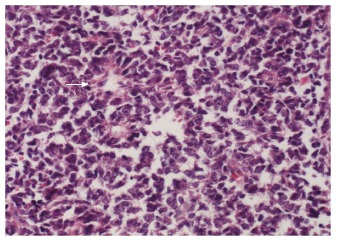

Figure 4.

Small round cells containing uniform vesicular and Homer-Wright rosettes were found microscopically (right arrow, × 200).

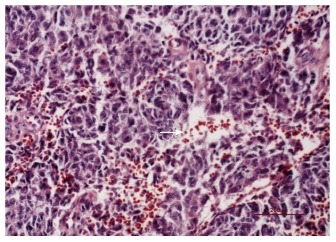

Figure 5.

Red blood cells were found between the tumor cells (right arrow, × 200).

DISCUSSION

PNET may occur anywhere in the body[5]. Batsakis et al[6] divided PNET into three groups based on the tissue of origin. Thiostrepton diminishes FOXM1 expression in Ewing cell lines and reduces cell viability through an apoptotic mechanism[7]. E-EWS/pPNET is a rare aggressive malignant small round cell tumor derived from the outer central and autonomic nervous systems. In ascending order by morbidity, the primary sites of pPNET are located in the neck, abdomen, retroperitoneum, pelvis and the chest wall. Particularly, E-EWS/pPNET of the small bowel is extremely rare. In addition, there are many patients who suffer from huge abdominal tumors, but do not have any clinical symptoms. Most of these patients die, because they do not receive treatment on time. In this study, we report a patient with a huge abdominal E-EWS/pPNET tumor and reviewed the other four cases (Table 1). In this case, the patient was brought to the attention of clinicians due to abnormal clinical manifestations (hematemesis and melena). As a result of these special clinical symptoms, the patient received timely intervention and the tumor was surgically removed. pPNET is a rare tumor, which can be found in a wide variety of tissues including the pancreas[8], neck[9], spine[10], prostate[11] and parotid[12]. It is categorized in the Ewing family of tumors and is composed of malignant small round cells[13-16]. The solid component of the tumors was enhanced on contrast-enhanced CT, but the cystic component was not[17]. According to the published medical literature, there have been only five cases of E-EWS/pPNET of the small bowel including the patient presented in this report[1-4]. pPNET is a rare malignant tumor that usually occurs in children[18-20]. Interestingly, compared to the other four documented cases, our 15-year-old patient, who had the second largest tumor in terms of diameter, is the only patient diagnosed at nonage. The tumor was found to have infiltrated the full-thickness of the jejunal wall, accompanied by hematemesis and melena, due to spontaneous rupture. However, the patient died of intra-abdominal recurrence three months later. In summary, such huge abdominal mass often disqualifies patients from surgical intervention with the exception of spontaneous rupture or hematemesis. However, without intervention, these masses would continue to grow and cause significant morbidity. Choosing not to surgically intervene and remove the neoplastic mass inevitably leads to a poor prognosis; and although risky, surgery can sometimes be beneficial in these cases. Therefore, we firmly believe that surgery should be considered a feasible option in such cases.

Table 1.

Reported cases of primary primitive neuroectodermal tumors of the small bowel mesentery

| Ref. | Year of publication | Age/gender | Liposarcoma size (cm) | Treatment | Outcome |

| Kim et al[4] | 2013 | 23/M | 11.0 × 6.0 | Segmental resection of the small intestine and omentectomy | Recurrence after one year |

| Bala et al[3] | 2006 | 57/F | 7.5 × 6.5 | Resection of the tumor en bloc with 90 cm of the ileum and cecum | 8 mo |

| Balasubramanian et al[2] | 2002 | 53/F | 25 × 20 | Resection of the tumor en bloc | No data |

| Horie et al[1] | 2000 | 40/M | 11.0 × 8.0 | Resection of the tumor en bloc and partial resection of the small intestine | Died of massive intra-abdominal recurrence 7 mo later |

| Present case (Liu et al) | 2015 | 15/M | 20 × 20 | Resection of the tumor and partial resection of the small intestine | Died of intra-abdominal recurrence 3 mo later |

COMMENTS

Case characteristics

A 15-year-old boy suffered from acute abdominal pain, accompanied by hematemesis and melena.

Clinical diagnosis

Abdominal tumor.

Differential diagnosis

Perirenal liposarcoma and gastrointestinal stromal tumor.

Laboratory diagnosis

Most laboratory data are normal, except for anemia.

Imaging diagnosis

Abdominal enhanced CT revealed a large ovoid solid and cystic tumor (20 cm × 20 cm × 10 cm), which was observed at the left upper quadrant.

Pathological diagnosis

Small round cells containing uniform vesicular and Homer-Wright rosettes were found microscopically.

Treatment

Resection of the tumor and partial resection of the small bowel.

Related reports

En bloc resection of the tumor is required.

Experiences and lessons

Surgery can sometimes be beneficial in these cases.

Peer-review

This is an interesting case that deserves to be published in the journal.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This case report is retrospective and was not antecedently reviewed by the Local Ethics committee of China Medical University.

Informed consent statement: The patient involved in this study gave his written informed consent authorizing use and disclosure of his protected health information.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest to this work.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: January 26, 2016

First decision: May 17, 2016

Article in press: June 16, 2016

P- Reviewer: Amaro F S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Lu YJ

References

- 1.Horie Y, Kato M. Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the small bowel mesentery: a case showing perforation at onset. Pathol Int. 2000;50:398–403. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2000.01045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balasubramanian B, Dinakarababu E, Molyneux AJ. Primary primitive neuroectodermal tumour of the small bowel mesentery: case report. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2002;28:197–198. doi: 10.1053/ejso.2001.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bala M, Maly A, Remo N, Gimmon Z, Almogy G. Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor of bowel mesentery in adults. Isr Med Assoc J. 2006;8:515–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim JM, Chu YC, Choi CH, Kim L, Choi SJ, Park IS, Han JY, Kim KR, Choi YL, Kim T. Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor with osseous component of the small bowel mesentery: a case study. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47:77–81. doi: 10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2013.47.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kushner BH, Hajdu SI, Gulati SC, Erlandson RA, Exelby PR, Lieberman PH. Extracranial primitive neuroectodermal tumors. The Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience. Cancer. 1991;67:1825–1829. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910401)67:7<1825::aid-cncr2820670702>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Batsakis JG, Mackay B, el-Naggar AK. Ewing’s sarcoma and peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor: an interim report. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1996;105:838–843. doi: 10.1177/000348949610501014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christensen L, Joo J, Lee S, Wai D, Triche TJ, May WA. FOXM1 is an oncogenic mediator in Ewing Sarcoma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishizawa N, Kumamoto Y, Igarashi K, Nishiyama R, Tajima H, Kawamata H, Kaizu T, Watanabe M. A peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor originating from the pancreas: a case report and review of the literature. Surg Case Rep. 2015;1:80. doi: 10.1186/s40792-015-0084-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bishop JA, Alaggio R, Zhang L, Seethala RR, Antonescu CR. Adamantinoma-like Ewing family tumors of the head and neck: a pitfall in the differential diagnosis of basaloid and myoepithelial carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:1267–1274. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tong X, Deng X, Yang T, Yang C, Wu L, Wu J, Yao Y, Fu Z, Wang S, Xu Y. Clinical presentation and long-term outcome of primary spinal peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumors. J Neurooncol. 2015;124:455–463. doi: 10.1007/s11060-015-1859-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liao C, Wu X, Wang X, Li H. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the prostate: Case report from China. J Cancer Res Ther. 2015;11:668. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.140759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalantari M, Deyhimi P, Kalantari P. Peripheral Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor (pPNET) of the Parotid: Report of a Rare Case. Arch Iran Med. 2015;18:858–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang C, Li B, Yu X, Xuan M, Gu QQ, Qian W, Qiu TT, Shen ZJ, Zhang MM. Radiological and clinical findings of osseous peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumors. Oncol Lett. 2015;10:553–559. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.West DC, Grier HE, Swallow MM, Demetri GD, Granowetter L, Sklar J. Detection of circulating tumor cells in patients with Ewing’s sarcoma and peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:583–588. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.2.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thorner P, Squire J, Chilton-MacNeil S, Marrano P, Bayani J, Malkin D, Greenberg M, Lorenzana A, Zielenska M. Is the EWS/FLI-1 fusion transcript specific for Ewing sarcoma and peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor? A report of four cases showing this transcript in a wider range of tumor types. Am J Pathol. 1996;148:1125–1138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Votta TJ, Fantuzzo JJ, Boyd BC. Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor associated with the anterior mandible: a case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:592–597. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan Y, Zhang H, Ma GL, Xiao EH, Wang XC. Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor: dynamic CT, MRI and clinicopathological characteristics--analysis of 36 cases and review of the literature. Oncotarget. 2014;5:12968–12977. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sorensen PH, Liu XF, Delattre O, Rowland JM, Biggs CA, Thomas G, Triche TJ. Reverse transcriptase PCR amplification of EWS/FLI-1 fusion transcripts as a diagnostic test for peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumors of childhood. Diagn Mol Pathol. 1993;2:147–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexiou GA, Sfakianos G, Dimitriadis E, Stefanaki K, Anastasopoulos J, Matsinos G, Prodromou N. Spinal dumbbell-shaped peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor in a child. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2013;49:119–120. doi: 10.1159/000356932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kushner BH, Meyers PA, Gerald WL, Healey JH, La Quaglia MP, Boland P, Wollner N, Casper ES, Aledo A, Heller G. Very-high-dose short-term chemotherapy for poor-risk peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumors, including Ewing’s sarcoma, in children and young adults. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2796–2804. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.11.2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]