Abstract

Numerous meta-analyses have been conducted aiming to compare hyaluronic acid (HA) and placebo in treating knee osteoarthritis (OA). Nevertheless, the conclusions of these meta-analyses are not in consistency. The purpose of the present study was to perform a systematic review of overlapping meta-analyses investigating the efficacy and safety of HA for Knee OA and to provide treatment recommendations through the best evidence. A systematic review was conducted based on the PRISMA guidelines. The meta-analyses and/or systematic reviews that compared HA and placebo for knee OA were identified. AMSTAR instrument was used to evaluate the methodological quality of individual study. The information of heterogeneity within each variable was fetched for the individual studies. Which meta-analyses can provide best evidence was determined according to Jadad algorithm. Twelve meta-analyses met the eligibility requirements. The Jadad decision making tool suggests that the highest quality review should be selected. As a result, a high-quality Cochrane review was included. The present systematic review of overlapping meta-analyses demonstrates that HA is an effective intervention in treating knee OA without increased risk of adverse events. Therefore, the present conclusions may help decision makers interpret and choose among discordant meta-analyses.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common degenerative disorder with rising prevalence. It leads to cause of disability among the older people1,2,3. In epidemiology, half of the world’s population aged 65 years or older has OA, which is the most prevalent disorder of articulating joints in humans. Knee OA is the most common type of OA. The symptoms of knee OA is characterized by pain and disability in joints. In pathologically, the following features are in knee joints: damage of articular cartilage at weight-bearing areas, change in subchondral bone, inflammation in synovitis, osteophyte formation, cyst formation and thickening of joint capsule and loss of joint space4. As some evidence showed, the significant risk factors for this excess mortality in OA included walking disability and cardiovascular disorder5. Thus, more attention should be paid to alleviation of pain and improvement of joint function in OA patients.

Hyaluronic acid (HA) is, as an integral component of synovial fluid, often used in clinical practice for treating knee OA. HA is regarded as a joint lubricant during shear stress and as a shock absorber during compressive stress. In the development of knee OA, a marked reduction in concentration and molecular weight of endogenous HA ultimately leads to reduced viscoelastic properties of synovial fluid and induction of proinflammatory pathways6. Therefore, the purpose of intra-articular injection of exogenous HA is to replace this OA-induced deficit and stimulate production of endogenous HA7. HA may alleviate symptoms of knee OA via multiple pathways including inhibition of chondrodegradative enzymes and inflammatory processes, stimulation of chondrocyte metabolism, and synthesis of articular cartilage matrix components8.

Although numerous meta-analyses have been conducted to determine the safety and efficacy of HA injections for knee OA, they showed different results in their studies9,10,11,12. In the recent guideline in treating Knee OA, AAOS reported that HA is not recommended in the treatment of Knee OA13. However, Altman et al.14 investigated ten guidelines regarding the use of HA for the treatment of knee OA and reported that the recommendations were highly inconsistent as a result of the variability in guideline methodology. Thus, the inconsistent recommendations make it difficult for clinical professionals to determine its appropriateness when treating knee OA.

The purpose of the present study is to perform a systematic review of overlapping meta-analyses determining the clinical effects of HA in treating Knee OA, to evaluate the mythological quality of included individual meta-analyses, and to take best evidence through the currently inconsistent evidence.

Materials and Methods

Search strategy

The present systematic review was conducted following the guideline of PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis) statement15. PRISMA statement was used to guarantee high-quality reporting of systematic reviews or meta-analyses16. Electronic databases including MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane library were searched for all meta-analysis or systematic review published through Nov 2015. The following MeSH items or free words were taken: osteoarthritis, knee, meta-analysis, systematic review, and hyaluronic acid. The references of searched studies were also reviewed to explore other meta-analyses or systematic reviews. No restrictions were made on the publication language.

Inclusive and exclusive criteria

Studies were considered eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria:

(1) Meta-analyses or systematic reviews only including randomized controlled trial (RCT);

(2) Meta-analyses or systematic reviews comparing HA with placebo in treating knee OA;

(3) Meta-analyses or systematic reviews reported at least one variable (such as pain, function, and safety).

Exclusion criteria included the following items:

(1) Meta-analyses or systematic reviews including non-RCT;

(2) Systematic reviews did not conducting meta-analysis or pooling data;

(3) Abstract, commentary, methodological study, narrative review.

Meta-analyses/systematic reviews selection

Firstly, two reviewers assessed the titles and abstracts of researched studies for the eligibility criteria independently. The two reviewers were not blinded to the journals, organizations, financial assistance, conflict of interest and researchers’ information. Subsequently, the full text of the studies that potentially met the inclusion criteria was read to determine the final inclusion. Any disagreement was resolved by reaching a consensus through discussion.

Date extraction

Two reviewers independently extracted the data from each included literature by the use of a standard data extraction form. The following items were extracted: title, authors, original study design, database, total number of studies, level of evidence, the pooled results and methodological variables.

Assessment of methodological quality

The quality assessment was independently conducted by two authors. Disagreements were resolved by discussion or a third reviewer was involved. The Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) method was used to evaluate the methodological quality of included studies17. The AMSTAR was a measurement scale containing eleven items, and it was applied extensively in assessing methodological quality of published meta-analysis or systematic review18.

Heterogeneity within included studies

Heterogeneity of each outcome (primary and secondary outcomes) was reported for the each included meta-analyses. The following two questions were also evaluated: whether sensitivity analysis was performed in meta-analysis and whether the included meta-analyses evaluated potential sources of heterogeneity across primary studies. Upon the Cochrane Handbook, Heterogeneity of each outcome between 0% and 40% is regarded as not important; between 30% and 60% is moderate; between 50% and 90% is substantial, and between 75% and 100% is considerable. Therefore, I2 less than 60% are accepted in the present study.

Choice of best evidence

Treatment recommendations were made according to the Jadad decision algorithm19. The methodological instrument confirmed the source of inconsistence between meta-analyses, including differences in clinical problem, inclusion and exclusion standard, extracted data, methodological quality assessment, data combining, and statistical analysis methods19. The application of algorithm was performed by two independent reviewers. Our evaluation group came to conformity as to which of included meta-analyses can provide best evidence based on the current information.

Results

Literature search

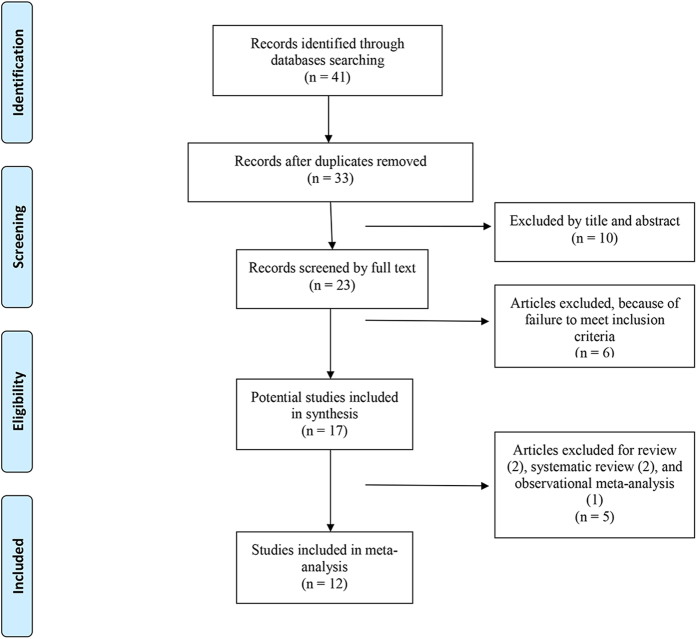

Thirty-three titles and abstracts were preliminarily identified with the first search strategy, of which 12 of the published meta-analyses6,9,10,11,12,20,21,22,23,24,25,26 ultimately met the eligibility criteria (Fig. 1). Two studies27,28 were excluded because they conducted network meta-analysis among each kinds of HA. Three meta-analyses29,30,31 were excluded because they were performed to compare the efficacy and safety of HA with corticosteroids. Three studies, including primary studies in ankle/hip joints, were also excluded32,33,34.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the study selection process.

Table 1 presented the characteristics of included meta-analysis. The number of original studies in meta-analysis varied from 5 in that study published in 2006 to 89 that published in 2012 (Table 2). All included meta-analyses conducted qualitatively data synthesis.

Table 1. General Description of the Characteristics of included Meta-Analyses.

| Authors | Journal | Date of Last Literature search | Date of publication | No. of included studies | No. of included RCTs | No. of grey literature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lo et al.20 | JAMA | February, 2003 | December, 2003 | 22 | 19 | 3 |

| Wang et al.21 | The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume | December, 2001 | March, 2004 | 20 | 20 | 0 |

| Modawal et al.22 | The Journal of family practice | August, 2004 | September, 2005 | 9 | 9 | 0 |

| Arrich et al.23 | CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association journal | April, 2004 | April, 2005 | 22 | 22 | 0 |

| Strand et al.24 | Osteoarthritis and cartilage | December, 2004 | September, 2006 | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Bellamy et al.25 | The Cochrane database of systematic reviews | December, 2005 | February, 2006 | 40 | 40 | 0 |

| Bannuru et al.9 | Osteoarthritis and cartilage | March, 2010 | Jun, 2011 | 49 | 49 | 0 |

| Rutjes et al.10 | Annals of internal medicine | January, 2012 | August, 2012 | 89 | 71 | 32 |

| Colen et al.26 | BioDrugs | June, 2011 | August, 2012 | 74 | 74 | 0 |

| Miller et al.11 | Clinical medicine insights. Arthritis and musculoskeletal disorders | June, 2013 | December. 2013 | 29 | 29 | 0 |

| Richette et al.12 | RMD open | December, 2013 | January, 2015 | 8 | 8 | 0 |

| Strand et al.6 | Journal of pain research | December, 2013 | May, 2015 | 29 | 29 | 0 |

Table 2. Primary Studies Included in Previous Meta-analyses.

| Primary Study | Lo et al.20 | Wang et al.21 | Modawal et al.22 | Arrich et al.23 | Strand et al.24 | Bellamy et al.25 | Bannuru et al.9 | Rutjes et al.10 | Colen et al.26 | Miller et al.11 | Richette et al.12 | Strand et al.6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adams et al. 1995 | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Altman et al. 1998 | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| Altman et al. 2004 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | − |

| Altman et al. 2009 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Anika et al. 2000 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Anika et al. 2001 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Ardic et al. 2001 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Atamaz et al. 2006 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Atay et al. 2008 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| Auerbach et al. 2002 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Baltzer et al. 2009 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| Baraf et al. 2009 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Bayramoglu et al. 2003 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| Bellamy et al. 2005 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Bragantini et al. 1987 | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| Brandt et al. 2001 | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| Bunyaratavej et al. 2001 | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | + |

| Butun et al. 2002 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Caborn et al. 2004 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Caracuel et al. 2001 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Carrabba et al. 1995 | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| Chevalier et al. 2010 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | + | − |

| Chou et al. 2009 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Cogalgil et al. 2002 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Cohen et al. 1994 | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Conrozier et al. 2009 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Corrado et al. 1995 | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| Creamer et al. 1994 | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| Cubukcu et al. 2004 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| Cubukcu et al. 2005 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | + |

| Dahlberg et al. 1994 | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| Day et al. 2004 | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| DeCaria et al. 2012 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + |

| Dickson et al. 1998 | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Dickson et al. 2001 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Diracoglu et al. 2009 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | + |

| Dixon et al. 1988 | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| Dougados et al. 1993 | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| Esteve de Miguel et al. 1995 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Formiguera et al. 1995 | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Forster et al. 2003 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Frizziero et al. 2002 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Genzyme et al. 2005 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Ghirardini et al. 1990 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Graf et al. 1993 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Graf von der Schulenburg et al. 1997 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Grecomoro et al. 1987 | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| Groppa et al. 2001 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Groppa et al. 2004 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Guler et al. 1996 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Henderson et al. 1994 | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| Heybeli et al. 2008 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| Hizmetli et al. 1999 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Hizmetli et al. 2002 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Huang et al. 2005 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Huang et al. 2011 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + |

| Huskisson et al. 1999 | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| Isdale et al. 1993 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Jorgensen et al. 2010 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | + |

| Jubb et al. 2003 | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| Juni et al. 2007 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Kahan et al. 2003 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| Kalay et al. 1997 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Karatosun et al. 2005 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Karlsson et al. 2002 | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| Kawasaki et al. 2009 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Kirchner et al. 2006 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Kosuwon et al. 2010 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Kotevoglu et al. 2006 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| Kul-Panza et al. 2010 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | + |

| Leardini et al. 1987 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Leardini et al. 1991 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Lee et al. 2006 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Lee et al. 2011 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Leopold et al. 2003 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Lin et al. 2004 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Listrat et al. 1997 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Lohmander et al. 1996 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| Lundsgaard et al. 2008 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| McDonald et al. 2000 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Miltner et al. 2002 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Moreland et al. 1993 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Nahler et al. 1996 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Nahler et al. 1998 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Navarro-Sarabia et al. 2011 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − |

| Neustadt et al. 2004 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Neustadt et al. 2005 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| Onel et al. 2008 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Ozturk et al. 2006 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Patrella et al. 2002 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Pavelka et al. 2010 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Payne et al. 2000 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Pedersen et al. 1993 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Petrella et al. 2002 | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Petrella et al. 2006 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | + | |

| Petrella et al. 2008 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| Petrella et al. 2009 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Pham et al. 2003 | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Pham et al. 2004 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| Pietrogrande et al. 1991 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Puhl et al. 1993 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Raman et al. 2008 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Raynauld et al. 2002 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| Raynauld et al. 2005 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Renklitepe et al. 2000 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Rolf et al. 2005 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | + |

| Russell et al. 1992 | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Rydell et al. 1972 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Sala et al. 1995 | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | + |

| Sanofi-Aventis et al. 2010 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Saravanan et al. 2002 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Scale et al. 1994 | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| Schneider et al. 1997 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Seikagaku et al. 2001 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Seikagaku et al. 2001a | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Sezgin et al. 2005 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Shichikawa et al. 1983 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − |

| Shichikawa et al. 1983a | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Shimizu et al. 2010 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Skwara et al. 2009 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Skwara et al. 2009a | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Stittik et al. 2007 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Strand et al. 2012 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + |

| Tamir et al. 2001 | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| Tascioglu et al. 2003 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Tekeoglu et al. 1998 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Tetik et al. 2003 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Thompson et al. 2002 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Tsai et al. 2003 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Ulucay et al. 2007 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Vanelli et al. 2010 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Weiss et al. 1981 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| Weiss et al. 1981a | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Westrich et al. 2009 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Wobig et al. 1998 | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| Wobig et al. 1999 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| Wu et al. 1997 | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | + |

| Wu et al. 2004 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − |

Search methodology

The literature search methodology which was adopted by included meta-analysis was present in Table 3. Most of the databases that the included studies searched were Medline, Embase or Cochrane database.

Table 3. Databases Mentioned by Included Meta-analyses during Literature Searches.

| Authors | Search Database |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medline | Embase | Cochrane | BIOSIS | EBSCO | Google Scholar | others | |

| Lo et al.20 | + | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Wang et al.21 | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Modawal et al.22 | + | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Arrich et al.23 | + | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| Strand et al.24 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Bellamy et al.25 | + | + | + | − | − | − | + |

| Bannuru et al.9 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Rutjes et al.10 | + | + | + | − | − | − | + |

| Colen et al.26 | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Miller et al.11 | + | + | −− | − | − | − | − |

| Richette et al.12 | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Strand et al.6 | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

Methodological quality of included meta-analyses

Methodological characteristics of included Meta-analyses were presented in Table 4. All included meta-analyses only included RCTs and/or quasi-RCTs. The evidence degree of each meta-analysis was Level II. REVMAN, STATA, SAS, R and Comprehensive Meta-analysis software were used in meta-analyses. Subgroup and sensitivity analysis were used in some of the included studies. None meta-analysis used GRADE in their study. The AMSTAR results with each question of included meta-analysis were shown in Table 5. The average score of AMSTAR of included meta-analyses was 7.25, ranging from 4 to 11. All included meta-analyses reported that there was no conflict of interest in making meta-analysis. One meta-analysis conducted by Bellamy et al.25 was the highest quality study.

Table 4. Methodological Characteristics of Included Meta-analyses.

| Authors | Primary study design | Level of evidence | Software | Sensitivity analysis | Subgroup analysis | GARDE evidence profiles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lo et al.20 | RCT | Level II | SAS | YES | -NO | NO |

| Wang et al.21 | RCT | Level II | STATA | NO | YES | NO |

| Modawal et al.22 | RCT | Level II | STATA | YES | NO | NO |

| Arrich et al.23 | RCT | Level II | STATA | YES | NO | NO |

| Strand et al.24 | RCT | Level II | SAS | NO | NO | NO |

| Bellamy et al.25 | RCT | Level II | REVMAN | YES | NO | NO |

| Bannuru et al.9 | RCT | Level II | R software | YES | YES | NO |

| Rutjes et al.10 | RCT or quasi-RCT | Level II | STATA | YES | YES | NO |

| Colen et al.26 | RCT | Level II | REVMAN | NO | NO | NO |

| Miller et al.11 | RCT | Level II | Comprehensive Meta-analysis | YES | NO | NO |

| Richette et al.12 | RCT | Level II | R software | NO | NO | NO |

| Strand et al.6 | RCT | Level II | Comprehensive Meta-analysis | YES | YES | NO |

Table 5. AMSTAR Criteria for Included Meta-analyses.

| Items | Lo et al.20 | Wang et al.21 | Modawal et al.22 | Arrich et al.23 | Strand et al.24 | Bellamy et al.25 | Bannuru et al.9 | Rutjes et al.10 | Colen et al.26 | Miller et al.11 | Richette et al.12 | Strand et al.6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Was a prior design provided? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Was there duplicate selection and data extraction? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Was a comprehensive literature search preformed? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Was the status of publication used as an inclusion criterion? | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Was a list of included/excluded studies provided? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Were the profiles of the included studies provided? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Was the methodological quality of the included studies evaluated and documented? | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Was the scientific quality of the included studies used appropriately in formulating conclusions? | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Were the methods used to combine the findings of studies appropriate? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Was the publication bias evaluated? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Were the conflicts of interest stated? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total score | 7 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 11 | 8 | 10 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 7 |

Heterogeneity Assessment

Table 6 presented the data of heterogeneity of each variable in each meta-analysis. The I2 value was adopted to calculate the heterogeneity among original studies as a measurement aiming to ascertain the inter-studies variability in all included meta-analyses.

Table 6. Heterogeneity of each outcome in included meta-analyses.

| Outcomes | Lo et al.20 | Wang et al.21 | Modawal et al.22 | Arrich et al.23 | Strand et al.24 | Bellamy et al.25 | Bannuru et al.9 | Rutjes et al.10 | Colen et al.26 | Miller et al.11 | Richette et al.12 | Strand et al.6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall pooled effect size | + | |||||||||||

| Lequesne index score (early) | + | + | ||||||||||

| Lequesne index score (late) | + | |||||||||||

| Knee function (early) | 66% | − | 79% | 54% | − | 54% | ||||||

| Knee function (late) | 62% | 69% | 69% | |||||||||

| Knee stiffness | 74% | |||||||||||

| Physical function | + | |||||||||||

| Pain with activities (early) | + | + | ||||||||||

| Pain with activities (early) | + | |||||||||||

| Pain during or immediately after exercise (early) | 81% | + | ||||||||||

| Pain during or immediately after exercise (late) | − | − | ||||||||||

| Patient global assessment (early) | + | |||||||||||

| Patient global assessment (late) | + | |||||||||||

| Pain at rest (early) | 94% | + | ||||||||||

| Pain at rest (late) | − | |||||||||||

| Knee pain outcomes (early) | + | − | + | 75% | + | 92% | 73% | 32% | 73% | |||

| Knee pain outcomes (late) | + | 32% | 75% | 75% | ||||||||

| WOMAC pain | + | |||||||||||

| WOMAC phsical function | + | |||||||||||

| Overall adverse events | + | − | − | + | − | − | ||||||

| Flare-ups | + | |||||||||||

| Injection-site reaction | − | |||||||||||

| Injection-site pain | - | |||||||||||

| Arthralgia | − | |||||||||||

| Arthropathy/arthrosis/arthritis | − | |||||||||||

| Back pain | − | |||||||||||

| Headache | − | |||||||||||

| Knee effusion | + | |||||||||||

| Discontinued due to adverse event | − | − | + | − | ||||||||

| Overall study withdrawal | − | − | ||||||||||

| Mortality | − |

+Has heterogeneity but not reported.

−No heterogeneity.

Results of Jadad Decision Algorithm

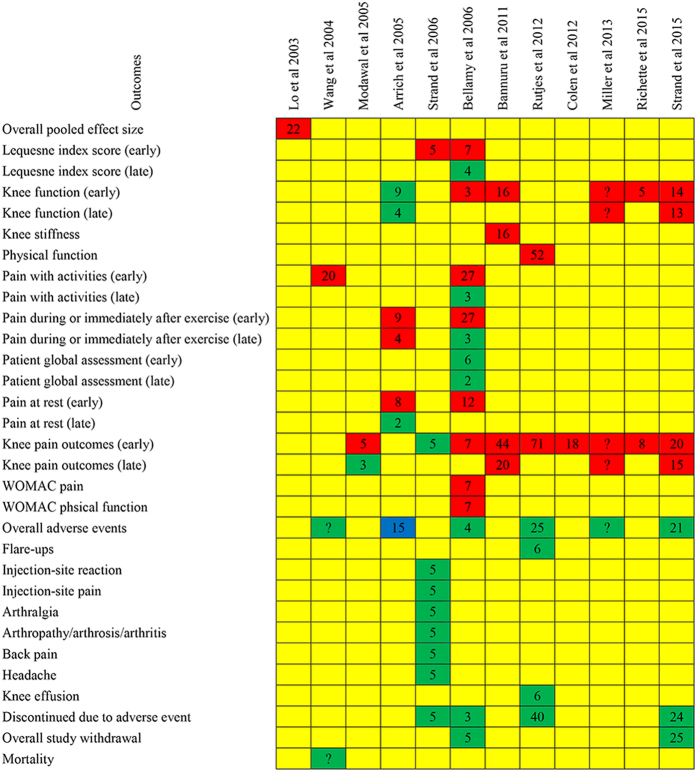

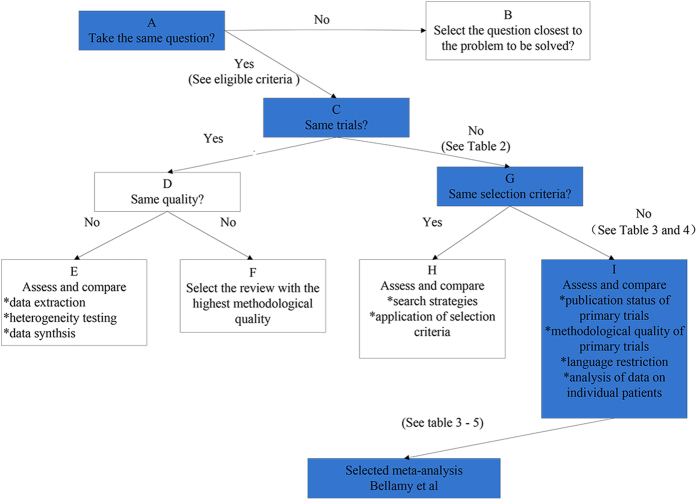

All outcomes reported in primary meta-analyses were reported in Fig. 2. According to the following three respects (the meta-analyses addressed the same clinical question, did not include the same original studies, and not have similar inclusion/exclusion criteria), the Jadad algorithm proposed that the eligible meta-analyses can be elected on account of the methodological quality and publication statue (Fig. 3). As a result, a Cochrane meta-analysis25 with highest quality was selected. Bellamy et al. supported the use of the HA in the treatment of knee OA with beneficial effects on pain, function and patient global assessment.

Figure 2. Results of each included meta-analysis.

Red means favoring hyaluronic acid; green means no difference; yellow means not reporting; and blue means favoring placebo. Arabic numerals mean the number of included randomized clinical trials.

Figure 3. Flow diagram of Jadad decision algorithm.

Discussion

According to the above mentioned methodology, the meta-analysis conducted by Bellamy et al.25 is with highest quality compared with others. The best available evidence hints that HA is an effective intervention in treating knee OA without increased risk of adverse events. Therefore, the current evidence supports the use of the HA in the treating knee OA.

Meta-analyses or systematic reviews are commonly regarded as the highest level of clinical evidence35. Clinicians can make meaningful clinical decisions with the help of meta-analyses or systematic reviews. However, a larger number of meta-analyses involving in the same clinical question have been published with conflicting results. This phenomenon was also occurred in the evidence-based study in HA injections for knee OA. Although numerous meta-analyses or systematic reviews have been written in treating knee OA via HA, there was still in controversy. Such discrepancy results in some difficulties for decision makers (including clinicians, policymakers and patients, depending on the context) who rely on this synthesized evidence to help them make decisions among pharmacological interventions when the results of trials are not unanimous.

Jadad et al.19 concluded the following potential sources of inconsistency among meta-analyses, including the clinical topic, eligible criteria, data extraction, quality assessment, assessment of the ability to combine studies, and statistical methods for data synthesis. Furthermore, Jadad et al.19 provided a decision methodological tool which summarizes the process for identifying and resolving causes of discordance. The ultimate purpose was to help clinical decision makers to select best evidence from inconsistency meta-analyses and systematic reviews. As recommended by Jadad et al., decision algorithm, a widely used tool36,37,38, is a useful instrument for differencing between meta-analyses or systematic reviews. Although Jadad decision algorithm choose comprehensive meta-analysis among discordant reviews, more empirical evidence is required to establish the effect of these elements on the validity of the review process, their relative importance and their effect on the results of a review.

According to the decision algorithm, the Cochrane meta-analysis conducted by Bellamy et al. was selected in the present study. Bellamy et al.25 reported that HA was an effective treatment for knee OA at different post injection periods but especially at the 5 to 13 week post injection period, and few adverse events were reported in the HA. However, there is considerable between-product, between-variable and time-dependent variability in the clinical response. Therefore, we concluded that HA is an effective and safety intervention in treating knee OA. Although the positive results were reported, effect size statistic was not used in the study. Thus, we did not have entire confidence in the extent of symptomatic improvement.

Rutjes and his colleagues10 published a high-quality systematic review (AMSTAR score: 10) in Annals of Internal Medicine. This study used effect size statistic and demonstrated that OA was associated with a small and clinical irrelevant benefit and an increased risk of adverse events. However, the use of the effect size statistic to infer clinically meaningful changes in efficacy outcomes is frequently misinterpreted. Rutjes et al. reported an effect size of 0.37 and then erroneously state that this is equivalent to an improvement in knee pain of 0.9 cm on a 10 cm scale. As showed in Table 1, Rutjes meta-analysis included largest number of RCTs (including published RCTs and grey literature). However, the conclusions in this paper were heavily influenced by inclusion of unpublished, unverifiable data.

The conclusion of the present study is consistent with the finding published in 2015 by Richette and his colleagues12. They performed a meta-analysis only including low bias and high-quality RCTs (adequate randomization and concealment and double-blind design) and showed that HA provided a moderate but real benefit for patients with knee OA. Recently, Strand et al.6 conducted a meta-analysis to investigate the safety and efficacy of UA-approved HA for knee OA. Strand’s study was the only known report to cite the pretreatment to posttreatment standardized mean difference. The statistic results represented very large treatment effects for HA. Thus, it reported that US-approved HA is safe and efficacious through 26weeks in treating knee OA.

The primary limitations of this meta-analysis include the following: (1) English language studies were included in the present overlapping meta-analyses. Although numerous meta-analyses were included in the present study, it is possible that we have omitted non-English language reviews. (2) Several factors of primary trials, such as study design, publication bias and clinical heterogeneity, may influence interpretation. (3) The selected meta-analysis was published in 2006, which will influence the stability of the results. Newest published high-quality meta-analyses are needed to confirm the present evidence.

To sum up, the present systematic review of overlapping meta-analyses investigated efficacy and safety of HA in treating Knee OA. Currently, the best evidence suggested that HA is an effective intervention in treating knee OA without increased risk of adverse events. Therefore, the evidence supports the use of the HA in the treating knee OA. Further studies with effect size statistic are still required to qualify the clinical efficacy.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Xing, D. et al. Intra-articular Hyaluronic Acid in Treating Knee Osteoarthritis: a PRISMA-Compliant Systematic Review of Overlapping Meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 6, 32790; doi: 10.1038/srep32790 (2016).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81501919 and no. 81357989).

Footnotes

Author Contributions D.X. and Y.X. conducted literature search and determined studies for exclusion and inclusion. D.X., Q.L., Z.L. and Y.K. extracted data from the included studies, performed quality assessment, and drafted the manuscript. J.L., D.X. and B.W. conceived the idea of the study, designed the study, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors reviewed the paper and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Sacks J. J., Luo Y. H. & Helmick C. G. Prevalence of specific types of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the ambulatory health care system in the United States, 2001–2005. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 62, 460–464 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence R. C. et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 58, 26–35 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmick C. G. et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 58, 15–25 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieppe P. A. & Lohmander L. S. Pathogenesis and management of pain in osteoarthritis. Lancet 365, 965–973 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg M. C. Mortality in osteoarthritis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 26, S120–S124 (2008). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strand V., McIntyre L. F., Beach W. R., Miller L. E. & Block J. E. Safety and efficacy of US-approved viscosupplements for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, saline-controlled trials. J Pain Res 8, 217–228 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. M. & Ghosh P. The synthesis of hyaluronic acid by human synovial fibroblasts is influenced by the nature of the hyaluronate in the extracellular environment. Rheumatol. Int. 7, 113–122 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg V. M. & Buckwalter J. A. Hyaluronans in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: evidence for disease-modifying activity. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 13, 216–224 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannuru R. R., Natov N. S., Dasi U. R., Schmid C. H. & McAlindon T. E. Therapeutic trajectory following intra-articular hyaluronic acid injection in knee osteoarthritis–meta-analysis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 19, 611–619 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutjes A. W., Juni P., da C. B. R., Trelle S., Nuesch E. & Reichenbach S. Viscosupplementation for osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 157, 180–191 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller L. E. & Block J. E. US-Approved Intra-Articular Hyaluronic Acid Injections are Safe and Effective in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized, Saline-Controlled Trials. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord 6, 57–63 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richette P. et al. Hyaluronan for knee osteoarthritis: an updated meta-analysis of trials with low risk of bias. RMD open 1, e000071 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G. A. AAOS clinical practice guideline: treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: evidence-based guideline. 2nd edition J Am Acad Orthop Surg 21, 577–579 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman R. D., Schemitsch E. & Bedi A. Assessment of clinical practice guideline methodology for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis with intra-articular hyaluronic acid. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 45, 132–139 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A. et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 339, b2700 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panic N., Leoncini E., de Belvis G., Ricciardi W. & Boccia S. Evaluation of the endorsement of the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement on the quality of published systematic review and meta-analyses. PLoS ONE 8, e83138 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea B. J. et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 7, 10 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea B. J. et al. External validation of a measurement tool to assess systematic reviews (AMSTAR). PLoS ONE 2, e1350 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadad A. R., Cook D. J. & Browman G. P. A guide to interpreting discordant systematic reviews. CMAJ 156, 1411–1416 (1997). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo G. H., LaValley M., McAlindon T. & Felson D. T. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid in treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis. JAMA 290, 3115–3121 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. T., Lin J., Chang C. J., Lin Y. T. & Hou S. M. Therapeutic effects of hyaluronic acid on osteoarthritis of the knee. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Bone Joint Surg Am 86-A, 538–545 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modawal A., Ferrer M., Choi H. K. & Castle J. A. Hyaluronic acid injections relieve knee pain. J Fam Pract 54, 758–767 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrich J., Piribauer F., Mad P., Schmid D., Klaushofer K. & Mullner M. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 172, 1039–1043 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strand V. et al. An integrated analysis of five double-blind, randomized controlled trials evaluating the safety and efficacy of a hyaluronan product for intra-articular injection in osteoarthritis of the knee. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 14, 859–866 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellamy N. et al. Viscosupplementation for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005321.pub2 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colen S., van den Bekerom M. P., Mulier M. & Haverkamp D. Hyaluronic acid in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis with emphasis on the efficacy of different products. BioDrugs 26, 257–268 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trojian T. H. et al. AMSSM Scientific Statement Concerning Viscosupplementation Injections for Knee Osteoarthritis: Importance for Individual Patient Outcomes. Clin J Sport Med doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095683 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannuru R. R. et al. Comparative effectiveness of pharmacologic interventions for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 162, 46–54 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F. & He X. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid and corticosteroids in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: A meta-analysis. Exp Ther Med 9, 493–500 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannuru R. R., Vaysbrot E. E., Sullivan M. C. & McAlindon T. E. Relative efficacy of hyaluronic acid in comparison with NSAIDs for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 43, 593–599 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannuru R. R. et al. Therapeutic trajectory of hyaluronic acid versus corticosteroids in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 61, 1704–1711 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang K. V., Hsiao M. Y., Chen W. S., Wang T. G. & Chien K. L. Effectiveness of intra-articular hyaluronic acid for ankle osteoarthritis treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 94, 951–960 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witteveen A. G., Hofstad C. J. & Kerkhoffs G. M. Hyaluronic acid and other conservative treatment options for osteoarthritis of the ankle. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 10, CD010643 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman J. R., Engstrom S. M., Solovyova O., Au C. & Grady J. J. Is intra-articular hyaluronic acid effective in treating osteoarthritis of the hip joint. J Arthroplasty 30, 507–511 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young D. Policymakers, experts review evidence-based medicine. Am J Health Syst Pharm 62, 342–343 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. et al. Surgical Versus Conservative Intervention for Acute Achilles Tendon Rupture: A PRISMA-Compliant Systematic Review of Overlapping Meta-Analyses. Medicine (Baltimore) 94, e1951 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell K. A. et al. Does Intra-articular Platelet-Rich Plasma Injection Provide Clinically Superior Outcomes Compared With Other Therapies in the Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis? A Systematic Review of Overlapping Meta-analyses. Arthroscopy 31, 2213–2221 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J. G., Wang J., Wang C. & Kan S. L. Intramedullary nail versus plate fixation for humeral shaft fractures: a systematic review of overlapping meta-analyses. Medicine (Baltimore) 94, e599 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]