Significance

Cockayne syndrome (CS) and xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) are photosensitive diseases with mutations in the nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway. XP patients have a very high incidence of UV-induced skin cancer, but CS patients have never been reported to develop cancer. Cultured cells from both diseases have similar sensitivity to UV-induced cytotoxicity. We examined UV-induced mutagenesis in cells from XP patients with mutations in the global genome repair branch of the NER pathway (XP-C cells) and CS primary cells using duplex sequencing for high sensitivity without selection. XP-C cells showed increased UV-induced mutation frequencies compared with normal cells, consistent with their increased cancer incidence. CS cells, in contrast, showed no elevated mutagenesis. Therefore the absence of cancer in CS patients results from the absence of increased mutations following UV exposure.

Keywords: mutagenesis, dipyrimidines, transcription arrest, apoptosis, RNA pol II

Abstract

Cockayne syndrome (CS) and xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) are human photosensitive diseases with mutations in the nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway, which repairs DNA damage from UV exposure. CS is mutated in the transcription-coupled repair (TCR) branch of the NER pathway and exhibits developmental and neurological pathologies. The XP-C group of XP patients have mutations in the global genome repair (GGR) branch of the NER pathway and have a very high incidence of UV-induced skin cancer. Cultured cells from both diseases have similar sensitivity to UV-induced cytotoxicity, but CS patients have never been reported to develop cancer, although they often exhibit photosensitivity. Because cancers are associated with increased mutations, especially when initiated by DNA damage, we examined UV-induced mutagenesis in both XP-C and CS cells, using duplex sequencing for high-sensitivity mutation detection. Duplex sequencing detects rare mutagenic events, independent of selection and in multiple loci, enabling examination of all mutations rather than just those that confer major changes to a specific protein. We found telomerase-positive normal and CS-B cells had increased background mutation frequencies that decreased upon irradiation, purging the population of subclonal variants. Primary XP-C cells had increased UV-induced mutation frequencies compared with normal cells, consistent with their GGR deficiency. CS cells, in contrast, had normal levels of mutagenesis despite their TCR deficiency. The lack of elevated UV-induced mutagenesis in CS cells reveals that their TCR deficiency, although increasing cytotoxicity, is not mutagenic. Therefore the absence of cancer in CS patients results from the absence of UV-induced mutagenesis rather than from enhanced lethality.

The nucleotide excision repair (NER) syndromes xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) and Cockayne syndrome (CS) lie at the extremes of increased cancer and neurodegeneration, respectively (1). The XP-C group of XP patients has mutations in the DNA damage-recognition protein XPC involved in global nucleotide excision repair (GGR). They are characterized by UV hypersensitivity, sun-induced cutaneous features such as hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation, and a greatly (>1,000-fold) increased incidence of cancer (1–3). In contrast, CS patients have mutations in the RNA polymerase II cofactors CSA and CSB, which recognize damage in transcribed regions through transcription arrest (transcription-coupled repair, TCR). CS patients are characterized by neurological and developmental symptoms such as early cessation of growth, microcephaly, mental retardation with dysmyelination, cachexia, and a greatly reduced life expectancy (1). The reported average life expectancy of patients with CS is only 12 y (4). CS patients are also highly photosensitive, burning and blistering after only minutes of sun exposure (5). However, in stark contrast to the dramatic increase in skin cancer incidence in XP-C patients, no CS patient has ever been reported to develop cancer, skin or otherwise (1, 4–8). Because cancer, especially in skin, is associated with mutagenesis (9, 10), we hypothesized that, unlike defects in GGR, which are associated with enhanced UV-induced mutagenesis in XP-C cells (11), the TCR defects in CS cells may not lead to increased mutagenicity.

Most sensitive mutagenesis studies in XP and CS cells have been confined to a few selectable genes, mutation of which confers drug resistance. Maher showed that UV-induced mutations in the hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT) gene that conferred resistance to 6-thioguanine (6-TG) were greatly enhanced in XP cells from both excision-defective and polymerase-defective groups (11, 12). Similar studies in CS cells, however, failed to show an increase in UV-induced mutations in HPRT, T-cell receptor, or glycophorin A gene loci (13). In contrast, an episomal plasmid (pZ189), irradiated with UV and passed through CS cells, showed increased levels of mutations (14, 15). The limitations of these methodologies include the small number of potential gene loci suitable for drug selection and the possibility that episomal vectors may not fully induce the DNA-damage response of whole cells, thereby resulting in a high mutation frequency that is not representative of mutagenesis in chromosomal loci. These limitations complicate the disparate results of these previous studies, leaving unresolved the question of whether CS cells demonstrate elevated UV-induced mutagenesis.

With the development of next-generation sequencing came the potential to survey multiple genes simultaneously and independently of selection. However, standard next-generation sequencing methodologies are highly error prone and are limited to surveying mutations present at ratios greater than 1 in 20 wild-type sequences (16). To counteract the limitations of standard next-generation sequencing platforms, we used duplex sequencing, a highly accurate sequencing method that is 100,000-fold more accurate than traditional next-generation sequencing methodologies. Because of its ability to remove sequencing artifacts resulting from DNA damage, as well as amplification and sequencing errors, duplex sequencing enables the detection of mutations as low as 1 in 108 nucleotides sequenced (17, 18).

To test our hypothesis that defects in TCR may not lead to increased UV-induced mutagenesis, unlike defects in GGR, we used duplex sequencing for high-sensitivity mutation detection in primary cells derived from normal patients and from patients with XP-C and CS. We found that, although primary XP-C and CS cells have similar sensitivities to UV-induced cell killing, the surviving cells in the two groups are radically different. Surviving XP-C cells exhibit high levels of UV-induced mutations; surviving CS cells do not.

Results

UVC- and UVB-Induced Cytotoxicity in Primary Cells.

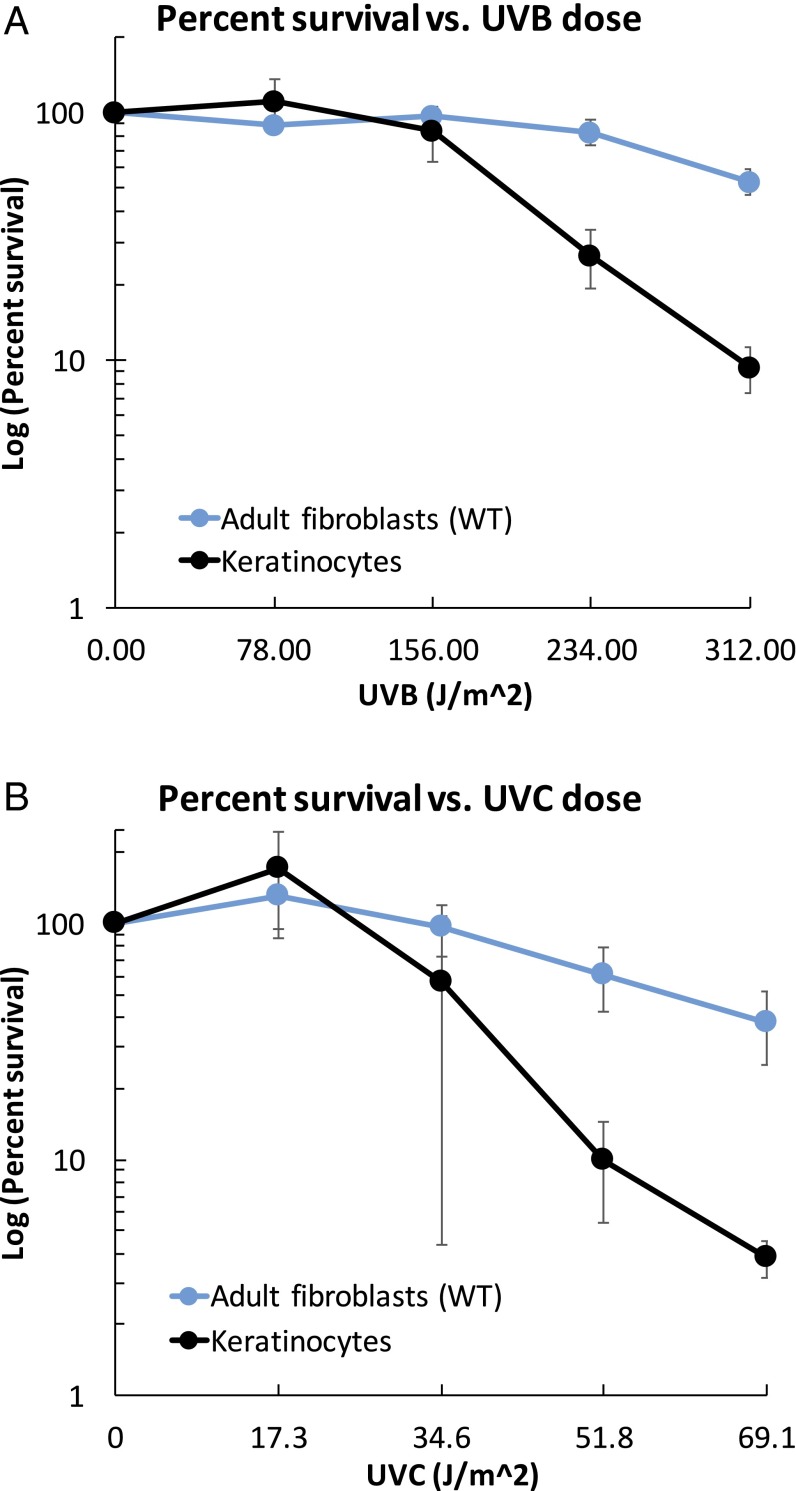

Primary fibroblasts (Table S1) derived from normal adult skin (GM05659) and normal neonatal primary foreskin (NHF-D) and primary neonatal keratinocytes were exposed to UVB or UVC, cultured for 5–7 d, and harvested. Using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (Sigma-Aldrich), we calculated the surviving fraction at the time of cell harvesting relative to untreated cells of the same genotype (Fig. 1). Primary keratinocytes were more resistant than fibroblasts to killing by UVB and UVC (Fig. S1).

Table S1.

Cells used for determination of UV survival and mutagenesis

| Genotype | Study designation | Source | 37% UVC dose, J/m2 | Mutations | |

| Coriell Institute | Alternate | ||||

| Normal fibroblasts | WT(1) | GM05659 | >44 | +/+ | |

| WT | GM03440 | >44 | +/+ | ||

| NHF-D | >44 | +/+ | |||

| Normal keratinocytes | Kerat | 32 | +/+ | ||

| XP-C | XPC(1) | GM02997 | XP7CA | 15.4 | Unavailable |

| XPC(2) | XP226BA | XP226BA | 13.4, 12.8 | 490delC homozygote | |

| CS-A | CSA(2) | GM01856 | CS3BE | 12.3, 16.8 | 37G > T; 479C > T |

| CS-B | CSB(1) | GM01428 | CS7SE | 11.9 | Unavailable |

| CSB(2) | GM01629 | CS1BE | 11, 13 | Exon10 (2087C > T); exon 18 (3615delA) | |

| Uncertain | CSA(1) | GM17536 | CS210BE | Not UV sensitive | Assignment uncertain, not XP or CSB |

Cell lines designated GMxxxxx were obtained from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences Human Genetic Cell Repository at the Coriell Institute for Medical Research. Normal neonatal NHF-D fibroblasts were from a single donor and were donated by D. Oh, University of California, San Francisco; the normal neonatal keratinocytes were a pooled culture obtained in house under Committee on Human Research permit. XP226BA cells were developed in house from tissue discarded from a cancer surgery.

Fig. 1.

Survival of normal adult (WT), normal neonatal (NHF-D), XP-C [XPC(1) and (2)], CS-A [CSA(2)], CS-B [CSB(1) and (2)], and GM17536 (originally designated “CS-A,) [CSA(1)] fibroblasts. Error bars represent SD of two survival determinations.

Fig. S1.

UV-induced cytotoxicity. Survival of normal fibroblasts (GM05659) and keratinocytes treated with UVB (A) and UVC (B).

Increased UVC-Induced Cytotoxicity in Repair-Deficient Primary Fibroblasts.

Normal (GM05659 and NHF-D), XP-C (GM02997 and XP226BA), CS-A (GM17536 and GM01856), and CS-B (GM01428 and GM01629) primary fibroblasts were exposed to UVC, cultured for 5–7 d, and harvested. Using the MTT assay, we calculated the surviving fraction at the time of cell harvesting relative to untreated cells of the same genotype. XP-C, CS-A, and CS-B primary fibroblasts were markedly more sensitive to killing by UVC than normal primary fibroblasts (Fig. 1), as is consistent with many previous studies reporting the enhanced UV sensitivity of XP and CS cells. One primary CS-A cell line, GM17536, appeared anomalous for CS-A and had higher survival rates than all other repair-deficient cells (Fig. 1 and Fig. S2A). We therefore excluded the GM17536 cell line from our subsequent mutational analyses.

Fig. S2.

GM17536 shows no difference from normal primary fibroblasts when exposed to UV or illudin S. (A) Survival of GM17536 (blue squares) and normal (red squares) primary fibroblasts exposed to increasing UV doses. (B) Survival of GM17536, XP-C (XP226BA), CS-A (GM1856), CS-B (GM01428), and normal (GM03440) primary fibroblasts exposed to increasing concentrations of illudin S. (C) Subclonal UV-specific mutations (C:G→T:A at Py–Py sites) in GM17536 and normal (GM05659) primary fibroblasts.

UVC and UVB Induce Subclonal Mutations in Normal Primary Cells.

To validate the use of duplex sequencing to detect mutagen-induced mutations, normal fibroblasts (GM05659 and NHF-D) and keratinocytes were exposed to UVB or UVC, cultured for 5–7 d, and harvested. Genomic DNA was then isolated and subjected to a single round of duplex sequencing (18). Target genes were exonic regions of NRAS, UMPS, PIK3CA, EGFR, BRAF, KRAS, F10, TP53, and TYMS (Table S2), several of which were chosen for their importance in skin carcinogenesis.

Table S2.

Genes captured for analyses by duplex sequencing

| Gene name | Orientation | Transcription status* |

| NRAS | Reverse | Active |

| KRAS | Reverse | Active |

| BRAF | Reverse | Inactive |

| TP53 | Reverse | Active |

| EGFR | Forward | Active |

| UMPS | Forward | Active |

| F10 | Forward | Active |

| PIK3CA | Forward | Inactive |

| TYMS | Forward | Inactive |

The spectrum of subclonal (<20% clonal) mutations observed in normal fibroblasts and keratinocytes showed a dose-dependent increase in C:G→T:A transitions as a function of UVB dose in primary keratinocytes and as a function of UVC dose in primary fibroblasts, especially in NHF-D cells (Fig. 2A). In contrast, transversions were dose independent. Of particular interest for UV-induced mutagenesis studies are C:G→T:A mutations at dipyrimidine sites (CpT, TpC, and CpC; hereafter referred to as “Py–Py” sites), because mutations at these sites are known signatures of UV-induced mutagenesis (19, 20). Importantly, when we examined the context of the C:G→T:A transitions, the majority of UV-induced mutations occurred at Py–Py sites and showed a dose-response to UVB and UVC in all normal genotypes (Fig. 2B). These results are consistent with previous reports of UV-induced mutagenesis in reporter genes (11, 13–15) and validate our use of duplex sequencing for the detection of UV-induced mutagenesis. We chose to carry out subsequent experiments using UVC because UVB and UVC produce similar mutagenic photoproducts. In our hands the difference in cyclobutane dimer yield per joule per meter was approximately a factor of 7, measured by the cleavage of a plasmid using Micrococcus luteus UV endonuclease.

Fig. 2.

UV induces unselected subclonal (<20% clonal) mutations in normal primary fibroblasts and keratinocytes. (A) Spectrum of subclonal mutations in adult (WT) and neonatal (NHF-D) fibroblasts treated with UVC and in keratinocytes (kerat) treated with UVB. (B) Subclonal frequencies of UV-specific mutations in adult and neonatal fibroblasts treated with UVC and in keratinocytes treated with UVB. Solid bars represent UV-specific mutations (C:G→T:A mutation at Py–Py sites); hashed bars represent C:G→T:A mutations at non-Py–Py sites. Frequencies were calculated by dividing the number of mutations of each type by the number of times the wild-type base of each mutation type was sequenced.

UVC Induces an Elevated Subclonal Mutation Frequency in XP-C Cells.

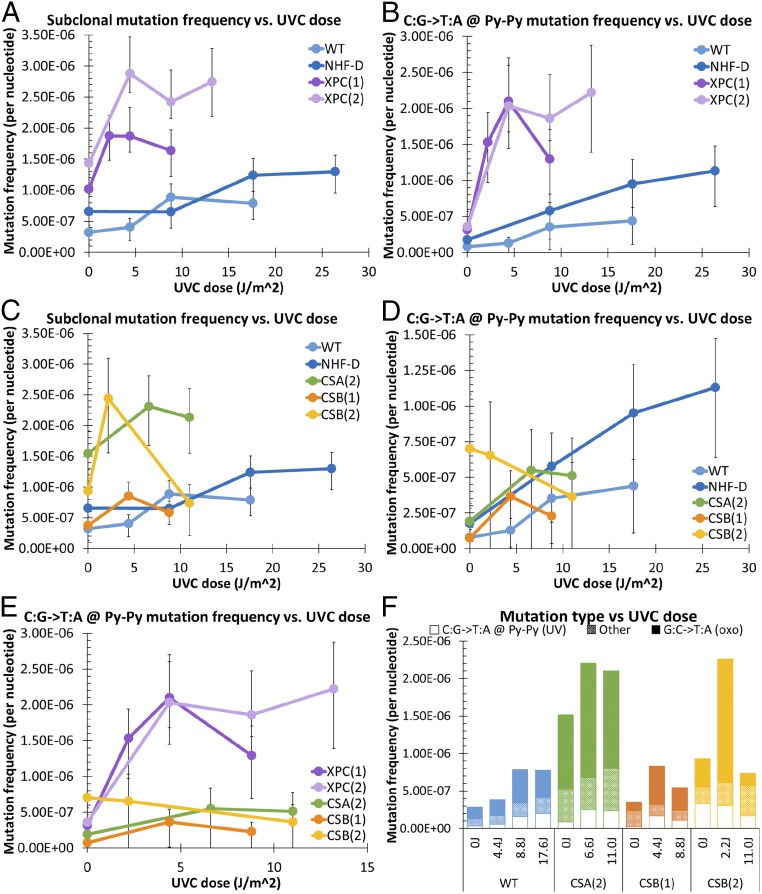

Normal (GM05659 and NHF-D) and XP-C (GM2997 and XP226BA) primary fibroblasts were exposed to UVC, cultured for 5–7 d, harvested, and subjected to a single round of duplex sequencing (18). XP-C cells showed elevated subclonal mutation frequencies relative to normal fibroblasts (Fig. 3A). When we focused on C:G→T:A mutations at Py–Py sites, we found that, relative to normal cells, XP-C cells accumulated more of these UV-specific mutations with increasing UVC dose (Fig. 3B). These results are consistent with previous reports, using reporter genes, of elevated UV-induced mutagenesis in XP cells (11). Additionally, normal cells showed a smaller, shallow increase in UV-specific mutations with UVC dose, as is consistent with efficient repair that minimizes UV-induced mutations and skin cancer initiation in repair-proficient cells (10).

Fig. 3.

UVC induces increased UV-specific mutations in primary XP-C cells, relative to primary normal cells, but not in primary CS cells. (A and B) Frequency of all subclonal (<20% clonal) mutations (A) and UV-specific mutations (B) in normal adult (WT) and neonatal (NHF-D) primary fibroblasts and in XP-C [XPC(1) and (2)] primary fibroblasts. (C and D) Frequency of all subclonal mutations (C) and UV-specific mutations (D) in normal adult (WT) and neonatal (NHF-D) primary fibroblasts and in CS-A [CSA(2)] and CS-B [CS-B(1) and (2)] primary fibroblasts. (E) UV-specific mutations in XP-C [XPC(1) and (2)] and CS-A [CSA (2)] and CS-B [CS-B(1) and (2)] primary fibroblasts. (F) Subclonal frequencies of UV-specific mutations, oxidative-signature mutations, and all other mutations in primary neonatal (NHF-D), CS-A [CSA (2)], and CS-B [CS-B(1) and (2)] fibroblasts. Open bars represent UV-specific mutations (C:G→T:A mutation at Py–Py sites); solid bars represent oxidative-signature mutations (G:C→T:A); hashed bars represent all other mutations. Frequencies were calculated by dividing the number of mutations of each type by the number of times the wild-type base of each mutation type was sequenced. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals calculated from Wilson scores of the mutation frequency for each sample.

CS Cells Fail to Demonstrate Elevated Subclonal Frequencies of UV-Specific Mutations upon UVC Exposure.

CS-A (GM01856) and CS-B (GM01428 and GM01629) primary fibroblasts were exposed to UVC, cultured for 5–7 d, harvested, and subjected to a single round of duplex sequencing (18). When we examined total subclonal mutations, all primary CS cells appeared to show an initial increase in mutation frequency, with a reduction at higher UVC doses (Fig. 3C). However, in contrast to XP-C cells, CS-A and CS-B fibroblasts showed no elevation in C:G→T:A mutations at Py–Py sites relative to normal fibroblasts (Fig. 3D). Indeed, when directly comparing XP-C and CS-A and -B cells (Fig. 3E), we found UV-specific mutations were markedly increased in XP-C fibroblasts, but there were none in CS-A/B fibroblasts despite their similar sensitivity to the cytotoxic effects of UVC (Fig. 1). When we examined the frequency of subclonal UV-specific mutations versus cell survival, the results suggested that CS cells might have an even lower mutation frequency than normal cells at equivalent survival levels (Fig. S3).

Fig. S3.

UVC-induced mutation frequencies versus survival in normal and CS-A and CS-B primary fibroblasts. (A and B) C:G→T:A (A) and C:G→T:A (B) mutations at CC:GG dinucleotides in normal adult (WT) and neonatal (NHF-D) fibroblasts and in CS-A [CSA(2)] and CS-B [CSB(1) and (2)] fibroblasts. Percent survivals were derived from cell survival rates in Fig. 1C. Frequencies were calculated by dividing the number of mutations of each type by the number of times the wild-type base of each mutation type was sequenced.

Because UV-specific mutations did not account for the initial increase in total subclonal mutations seen in CS cells (Fig. 3C), and particularly in CS-B cells, we sought to determine if the UV-induced mutations in CS cells had an oxidative-damage signature, because CS-B has been implicated in oxidative DNA-damage repair (21–23). Indeed, we found that the majority of UV-induced mutations in CS-B cells were G:C→T:A mutations, a signature of 8-oxo-dG–induced mutagenesis (Fig. 3F), which can be caused by direct oxidation of DNA by UV and, more indirectly, by singlet oxygen formation in cells following UV irradiation (24–26). This result is consistent with increased mutagenesis resulting from deficient oxidative DNA-damage repair in CS cells.

Duplex Sequencing Enables In-Depth Analyses of the Mutagenic Consequences of UVC.

Because duplex sequencing allows us to study rare mutational events, we examined the distribution of UVC-induced mutations by combining all cells exposed to UV doses into a pool, designated “UVC,” and comparing the mutations in these cells with those in untreated cells, designated “control” (Table 1 and Fig. S4). We determined the distribution of UVC-induced mutations in active and inactive genes based on the gene-expression status of each gene in skin (GeneCards; www.genecards.org/) and the distribution of mutations in the template (transcribed) and coding (nontranscribed) strands of active genes (Table 1, Fig. S4, and Table S2). In XP-C cells, there was an increased ratio of C:G→T:A mutations in inactive genes, relative to active genes; there also was an elevated ratio of C→T mutations in the coding strand of active genes, relative to the template strand. These biases are consistent with the GGR deficiency of XP-C cells. In CS-B cells, there was little difference in the ratios of C:G→T:A mutations as a function of gene activity; there was, however, an elevated ratio of C→T mutations in the template strand, relative to the coding strand, as is consistent with the TCR deficiency of CS-B cells. Thus, although TCR deficiency influences the strand distribution of mutations, it does not increase the overall yield.

Table 1.

Ratio of pooled C:G→T:A and C→T mutations after UV irradiation, relative to controls

| Genotype | |||

| Gene expression and transcription | Normal | CS-B | XPC |

| Gene-expression status* | |||

| Expressed | 2.9 | 6.0 | 3.4 |

| Not expressed | 2.1 | 5.5 | 7.4 |

| Strand of active genes, relative to transcription† | |||

| Nontranscribed (coding) | 5.8 | 4.2 | 5.3 |

| Transcribed (template) | 2.5 | 7.7 | 2.9 |

Because these ratios are calculated relative to controls of the same genotype, the absolute numbers are cell-type dependent. The ratios should be compared according to gene activity or strand specificity for each cell type independently.

C:G→T:A mutations at C:G base pairs.

C→T mutations in active genes at cytosines.

Fig. S4.

UVC-induced mutations accumulate preferentially in the inactive genes of XP cells and in the coding strand of the active genes of CS cells. (A–C) Mutation spectrum in active (black bars) versus inactive (gray bars) genes in primary normal neonatal (A), CS-B (B), and in XP-C (C) fibroblasts. Hashed bars indicate mutation frequencies in control groups; solid bars indicate mutation frequencies in pooled UV-treated groups. (D–F) Mutation spectrum in the coding (nontranscribed) strand versus the template (transcribed) strand primary normal neonatal (D), CS-B (E), and XP-C (F) fibroblasts. Frequencies were calculated by dividing the number of mutations of each type by the number of times the wild-type base of each mutation type was sequenced. Hashed bars indicate mutation frequencies in active genes of control groups; solid bars indicate mutation frequencies in active genes of pooled UV-treated groups.

During our analysis we observed 39 instances of multiple mutations within the same read (multiplets). Because the “classic” UV-induced mutation signature is the CC→TT mutation, we were intrigued by the presence of multiple other types of multiplet mutations (Table S3). Although CC→TT mutations are the most frequent type of multiplet mutation observed, we encountered many other types, all of which occurred in UV-treated cells. Of 39 multiplet mutations, all but one occurred at or directly adjacent to a Py–Py (CpC, CpT, TpC, TpT) dinucleotide, as is consistent with the mutations resulting from error-prone bypass of UV-induced damage. In addition to mutations that occurred within a doublet (i.e., CC→TT) or triplet (i.e., CTC→TTT), six of the multiplet mutations were two single mutations occurring 3–7 nt apart.

Table S3.

UVC-induced multiplet mutations in normal, XP-C, CS-A, and CS-B fibroblasts

| Fibroblast type | Active genes | Inactive genes | ||

| Exonic | Intronic | Exonic | Intronic | |

| Normal, adult | CC→TT | CC→TT | AC→TT | |

| GAA→AAC | ||||

| AC→GT | ||||

| Normal, neonatal | CC→TT | C→T and A→C in the same read | T→C and C→T in the same read | |

| CC→TT | ||||

| XPC(1) | G→T 7 nt apart | GA→AT | CTT→TTC | |

| AC→TT | TG→CT | |||

| TTT→ATC | ||||

| CCC→GCT | ||||

| CC→TT | ||||

| CC→TT | ||||

| AC→TT | ||||

| GTC→TTT | ||||

| CTC→TTT | ||||

| TC→AA | ||||

| CA→AG | ||||

| XPC (2) | CTC→TTT | AC→TG | ATC→TTT | |

| CTC→TTT | CC→AT | CAC→TTA | ||

| CTC→TTA | A→T and A→G in the same read | AT→TA | ||

| AC→CT | ||||

| CSA(2) | C→G and C→G in the same read | CA→AG | CC→TT | |

| CS-B(1) | CC→TT | |||

| CS-B(2) | AA→GG | |||

| C→T 6 nt apart | ||||

Discussion

Both XP and CS patients have defects in NER. The XP-C patients display extreme UV sensitivity and are highly prone to develop skin, corneal, and eyelid cancers because of their defects in GGR. CS patients, defective in the TCR branch of NER (1, 27), present a very different clinical picture, one of developmental defects and neurodegeneration; many but not all patients are also photosensitive, some developing blistering sunburns (5, 28). In contrast to XP-C patients, no known CS patient has ever developed cancer (4, 5, 8). Early studies of CS presented a discordant picture as to whether CS cells show a higher frequency of UV-induced mutation relative to normal cells and differed depending on the method used. Therefore, to determine definitively whether CS cells show an elevated frequency of UV-induced mutations, we used duplex sequencing, a highly accurate next-generation sequencing methodology that enables the detection of rare mutagenic effects (18), to study UV-induced mutagenesis in primary cells derived from normal persons and from XP-C, and CS-A and -B patients. In contrast to previous methods, our use of duplex sequencing (18) enabled us to study the mutagenic consequences of UV damage independent of selective pressures and in far greater detail than previously possible.

Our study of normal fibroblasts and keratinocytes validated our use of UVC to induce subclonal UV-specific mutations (C:G→T:A at Py–Py sites); we also validated our application of duplex sequencing to analyze the mutagenic consequences of UV in primary cultured cells absent selective pressures. Our analysis of the mutation spectrum in UVC-treated primary fibroblasts and UVB-treated primary keratinocytes revealed an elevated frequency of nearly all mutation subtypes in the keratinocytes, relative to the primary fibroblasts (Fig. 2). Interestingly, although the UV-induced C:G→T:A mutation showed the expected dose-response to UVB treatment, other mutations present in the untreated keratinocytes remained largely unchanged, indicating that these mutations were already present in the population. This increase in global subclonal mutations is not caused by differences in culture duration of fibroblasts and keratinocytes, because the keratinocytes were used at a lower passage number than the fibroblasts. The most prevalent mutation type was the G:C→T:A transversion (Fig. 2A), possibly reflecting the mutagenicity of guanine oxidative products produced in culture under ambient oxygen concentrations (29–31).

When we analyzed the mutation frequency in unirradiated human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT)-immortalized normal (GM05659T) and CS-B (GM01428) cells, which had been maintained in culture for ∼2 y, we found that their mutation frequency was more than an order of magnitude above that in the corresponding primary fibroblasts (Fig. S5A). These cells also had developed aneuploidy and increased copy numbers (Fig. S6 A–C). Following UV irradiation, there was a greater than eightfold reduction in the frequency of subclonal mutations (Fig. S5), in sharp contrast to our results with primary cells. The mutation frequencies remained above those seen in UV-irradiated primary fibroblasts and so masked direct UV mutagenesis. We attribute this reduction to UV damage-induced “bottle-necking” of the population, resulting in a reduction in the population’s subclonal mutation frequency (see SI Methods for further discussion). Such high mutation frequencies represent a caution in the use of immortalized cells for mutagenesis studies. Although some reports claim that hTERT-immortalization is nonmutagenic and maintains diploidy during extended culture (32, 33), our observations, and those of others (34–36), suggest instead that continued in vitro proliferation under ambient oxygen can itself be mutagenic.

Fig. S5.

UV-induced mutation frequency changes in hTERT-immortalized cells. (A) High mutation frequencies in untreated hTERT-immortalized normal (navy) and CS-B (green) cells and reduction by UV exposure. (B) Reduction in subclonal variant frequencies with UV dose representing UV-induced population bottle-necking in hTERT-immortalized normal (navy) and CS-B (green) cells.

Fig. S6.

Gene amplification in hTERT+ cells. (A) Copy number for selected genes in hTERT-transfected fibroblasts that had been grown continuously for at least 2 y. Probes used are indicated in the x axis. GM05659T, blue bars; GM01428T, red bars. Error bars indicate SD. (B) Large GM05659T cell labeled with probes for 17q24 (red) and chromosome 6 (green); the outline of the cell is marked by the dashed white line. (C) GM01429T cell labeled with probes for 6q14 (red) and chromosome 5 (green); the outlines of three cell nuclei are marked by white dashed lines. (D) GM05659T chromosome spread labeled with probes for 17q24 (red), chromosome 2 (green), and chromosome 9 (blue). (E) GM01428T chromosome spread labeled with probes for 17q24 (red), chromosome 2 (green), and chromosome 9 (blue). (Scale bars: 20 μ.)

Confirming previous reports (11), our duplex sequencing analysis of XP-C primary cells revealed increased UV-specific mutations after UVC irradiation, relative to normal primary cells. This elevated UV-induced mutagenesis occurred primarily in inactive genes, as evident from the greater than twofold increase in C:G→T:A mutations in inactive genes versus active genes, as is consistent with defective GGR (Table 1 and Fig. S4C). The bias between the template (transcribed) and coding (nontranscribed) strands in XP-C cells was similar to that of the normal cells (Table 1 and Fig. S4F), indicating that, despite the GGR deficiency, TCR of the template strand is unaffected.

In contrast to XP-C primary cells, CS-B primary cells showed no increase in UV-specific mutations following UVC irradiation, relative to normal primary cells (Fig. 3D), despite having a survival profile akin to that of XP-C cells (Fig. 1C). Similar to normal cells, CS-B fibroblasts showed no bias in the accumulation of C:G→T:A mutations between active and inactive genes (Table 1 and Fig. S4 A and B), as is consistent with proficient GGR. However, in contrast to both normal and XP-C primary fibroblasts, both of which had reduced C→T mutations in the template strand of active genes relative to the coding strand, CS-B cells had increased C→T mutations in the template strand (Table 1 and Fig. S4 D–F). This bias is consistent with defective TCR in CS-B primary cells.

An interesting observation in our in-depth spectrum studies is that, in contrast to normal and XP-C cells, CS-B primary fibroblasts accumulated more G:C→T:A mutations than C:G→T:A mutations upon UVC irradiation (Fig. 3F and Fig. S4B). Because G:C→T:A mutations are a signature of mutagenesis induced by 8-oxo-dG, the most common oxidative lesion in cells (37), this observation alludes to CSB’s additional role in oxidative DNA-damage repair (21–23), loss of which could result in increased oxidative damage-induced mutagenesis. We previously reported that CSB interacts with complex I of the mitochondria to quench surplus reactive oxygen species (38). Given the neurological involvement in CS, further studies on the mutagenic consequences of oxidative DNA damage may be worthwhile for understanding the pathologies seen in CS.

In addition to the gene- and strand-specific analyses afforded by our duplex sequencing approach, we gained greater insight into the mutational consequences of UVC-induced damage, beyond that of C:G→T:A mutations at Py–Py sites. Specifically, we observed numerous types of multiplet mutations (Table S3). These included the classic signature of UV-induced mutagenesis, CC→TT, and also extended to triplets, such as CTC→TTT, and doublet mutations spaced 3- to 7-nt apart. These multiplet mutations are likely the consequence of error-prone bypass polymerization during translesion synthesis and are consistent with the processivity of bypass polymerases persisting for several nucleotides after the bypass-requiring blocking lesion (39–41).

Our results reveal that UV-induced mutagenesis is no higher in CS cells than in normal cells (Fig. 3D and Fig. S3). In normal individuals, the average age of skin cancer incidence is 55 y (2), 33 y beyond the average lifespan of a CS patient and, indeed, 24 y longer than the lifespan of the longest-lived CS patient on record (31 y) (42). Although increased exposure to sunlight or use of tanning beds can result in much earlier diagnosis of skin cancers (early in the third decade of life) in normal individuals (43, 44), this age of onset is still a decade beyond the average lifespan of a CS patient. Thus, if CS cells accumulate mutations in response to UVC at the same rate as normal cells, CS patients simply do not live long enough to develop cancer. However, when analyzing UV-specific mutations plotted relative to survival, it appears that UV-induced mutagenesis might even be lower in CS cells than in normal cells (Fig. S3). This possibility suggests that, even if CS patients could attain normal lifespans, they might never get cancer; TCR deficiency may even be protective against UVC-induced mutagenesis. Further experiments examining normal versus CS cells would be necessary to determine if mutation frequencies are indeed lower in CS cells than in normal cells.

In conclusion, we have determined that, in human cells, defects in TCR fail to increase UV-induced mutagenesis as defects in GGR do. Thus, CS patients, defective in TCR, fail to develop cancer because they do not accumulate mutations more quickly than repair-proficient individuals.

SI Methods

Cell Cultures and Identification of GM17536.

The UV sensitivity and other characteristics of the fibroblasts and keratinocytes were determined from survival data (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1) and published data (https://catalog.coriell.org) (Table S1) (45, 46).

The source patient for the GM17536 cell line was originally described as “atypical Cockayne” and showed many of characteristics associated with the CS phenotype, including developmental delay, short lifespan, and ganglial calcifications, but little photosensitivity. The cell line was reported to show reduced reactivation of UV-damaged luciferase plasmids (https://catalog.coriell.org). Although it was originally classified as CS-A by the donor, this classification was by default, based on the exclusion of CS-B mutations and all groups of XP; it has since been reclassified as uncertain because of our observations.

To determine whether GM17536 cells have a significant sensitivity to UV, we determined its survival over a higher UVC dose range than that used for our mutagenesis analyses. GM17536 showed no increased UVC-induced cytotoxicity, relative to normal cells (Fig. S2A). We also determined the sensitivity of GM17536 to illudin S, which is uniquely toxic for cells that lack TCR (47), and found that GM17536 cells show no more sensitivity than TCR-proficient normal (GM03440) and XP-C (XP226BA) cells (Fig. S2B). In contrast, CS-A (GM01856) and CS-B (GM01428) cells were very sensitive to illudin, as is consistent with their TCR deficiencies. Additionally, the induction of subclonal UV-specific mutations (C:G→T:A at Py–Py sites) in GM17536 was within the normal cell range (Fig. S2C).

The GM17536 cell line therefore may possess a mutation in another gene peripherally involved in CS that remains to be identified. It should be noted that photosensitivity is not always a hallmark of CS (5, 28), which is predominantly a developmental and neurological disease.

Duplex Sequencing Procedures and Data Analysis.

To measure UV-induced mutations, we carried out Duplex Sequencing library preparations, as previously described (18), with the following minor modifications: (i) 3 μg of total DNA was sheared using the Covaris AFA system with a duty cycle of 10%, intensity of 5, 100 cycles per burst, time 20 s × 5, temperature 4 °C; (ii) before adapter ligation, the DNA was quantified and a 20:1 molar excess of adapters was used for the ligation step; (iii) after adapter ligation and cleanup, the library was requantified, and 1,200 fmol of product was amplified by PCR for 16–18 cycles. The resulting libraries were then subjected to two sequential rounds of gene capture with 120 oligonucleotide probes against the exomes of NRAS, UMPS, PIK3CA, EGFR, BRAF, KRAS, F10, TP53, and TYMS, several of which were chosen because of their importance in skin carcinogenesis. The final libraries were then sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq. 2000/2500 platform using 101-bp paired-end reads.

The overall sequencing pipeline has been described previously (18). Briefly, all raw sequencing reads are filtered based on the location of an expected fixed sequence within each read as well as the requirement that each position of the 12-nt random duplex tag sequence contain only one of the four canonical bases. Any reads not conforming to these criteria are discarded. The random tag sequences from each read pair are computationally concatenated into a 24-nt random sequence and are appended to the header of each read-pair. To remove potential artifactual mutations arising from the end-repair and ligation reactions, each read is trimmed by four additional bases. The reads then are aligned against build 19 of the human genome using the Burrows–Wheeler Aligner (BWA) (48). Reads not aligning to the human genome are filtered out. A consensus sequence (SSCS) for each tag family (e.g., reads sharing identical tag sequences) is computationally determined using software written in house. The consensus for any position in a read is considered undefined if the position is represented by fewer than three instances in the family or if less than 70% of the sequences at that position in the read are in agreement. The SSCS reads then are realigned to build 19 of the human genome using BWA. After filtering for unmapped reads, duplex consensus (DCS) reads are constructed by pairing SSCS with their respective strand-mates by grouping the 24-nt tag in read 1 with the appropriate 24-nt tag in read 2, and the sequence identity at each position of one read is compared with the sequence identity at the position in the other read. The sequence information is kept only if the base identity of the two reads is identical. Next, to remove alignment artifacts common at the ends of reads, 10 nt from each end of the duplex reads are soft-clipped using the Genome Analysis Toolkit. Finally, any nucleotides overlapping the forward and reverse reads of the DCS families are clipped to prevent double-counting. Scripts to calculate mutation frequencies and locations, written in house, are available upon request. Because of the high redundancy of the sequencing data in duplex sequencing, relatively few “genome equivalents” are sequenced (∼1,000–2,000 genomes per sample); thus, our ability to detect deletions and rearrangements is limited, and deletions and rearrangements were not evaluated in this study.

Subclonal mutation frequencies were initially plotted against UV dose to indicate the overall yield for each cell type (Fig. 3). When we plotted subclonal mutation frequencies versus cell survival, the results suggested that CS cells might have an even lower mutation frequency than normal cells at equivalent survival levels (Fig. S3). This possibility warrants further study.

We determined the distribution of mutations between active and inactive genes based on the gene-expression status of each gene in skin (Table S2) (GeneCards, www.genecards.org/) and the distribution between transcribed and nontranscribed strands. This determination was done by pooling controls and all UV doses for each cell type (Table 1, Fig. S4, and Table S2). In normal foreskin fibroblasts (NHF-D), the increase in C:G→T:A mutations in active genes was similar in active and inactive genes, 2.9-fold and 2.1-fold increases over control, respectively (Table 1). This finding implies that, in normal cells, there is no bias in mutagenic processes between active and inactive genes (Fig. S4). CS cells showed a similar relationship between active and inactive genes (a 6.0-fold increase in C:G→T:A mutations in active genes and a 5.5-fold increase in inactive genes) (Fig. S4). In contrast, XP-C cells showed a 3.4-fold increase in C:G→T:A mutations in active genes and a 7.4-fold increase in C:G→T:A mutations in inactive genes (Fig. S4). This increased mutagenesis in inactive genes relative to active genes in XP-C cells is consistent with their defective GGR but still proficient TCR.

Next, we determined the distribution of mutations between the template (transcribed) strand and coding (nontranscribed) strand (Table 1 and Fig. S4 D–F). The strand distribution of mutations in normal cells showed that C:G→T:A mutations increased 5.8-fold on the coding strand versus only 2.5-fold on the template strand, as is consistent with proficient TCR of the template strand (Fig. S4 D–F). CS cells showed a similar 4.2-fold increase in the coding strand; however, the template strand of CS cells showed a 7.7-fold increase in C:G→T:A mutations, as is consistent with defective TCR of the template strand of active genes in CS cells. In contrast, XP-C cells were similar to normal cells, showing a 5.3-fold increase in C:G→T:A mutations in the coding strand versus a 2.9-fold increase in the template strand, as is consistent with functional TCR of the template strand (Fig. S4 D–F).

We observed numerous types of multiplet mutations (Table S3). These included the classic signature of UV-induced mutagenesis, CC→TT, and triplet (e.g., CTC→TTT) and doublet mutations spaced 3- to 7-nt apart. These multiplet mutations are likely the consequence of error-prone bypass polymerization during translesion synthesis (40).

Mechanisms of Mutation Avoidance.

Our results are consistent with the presence of increased photosensitivity and the absence of skin cancer in CS. The question arises: Why does reduced repair of the template strand increase cell killing by UV damage but fail to increase mutagenesis? Because mutations need to be fixed by DNA replication across a photoproduct site, one possibility is that collisions between advancing replication forks and an arrested transcription complex trigger apoptosis in replicating CS cells (49). A role for DNA replication arrest in CS cells has long been known (50, 51) and has been advanced as an apoptosis factor in CS (52, 53). Noncanonical activation of ATM (54) may be the cause of such delay in DNA replication (50, 51), limiting mutagenic bypass of lesions. Furthermore, prolonged transcription blockage has itself been shown to trigger p53-independent apoptosis, mediated by the JNK pathway, in TCR-deficient cells (55). Additionally, because TCR plays an important role in processing R-loops (56), the TCR deficiency in CS may result in elevated R-loop levels, posing persistent blocks to RNA polymerase progression and inducing apoptosis, further exacerbating cytotoxicity.

Interpreting our mutagenesis results in this light, we propose the following potential explanation for the divergent phenotypes of XP-C and CS despite their similar molecular defects. In XP-C, cells not killed by UV have increased mutations and undergo gene-expression changes (57). Consequently, genes not previously subject to TCR, and likely harboring mutations resulting from error-prone bypass of UV-induced lesions during replication, become expressed. The clonal expansion of these mutated cells (42) leads to the development of skin cancer. In contrast, in CS, cells not killed by UV have little if any increase in mutation load. The expansion of these nonmutated cells to replace the cells lost to the cytotoxic effects of UV does not lead to skin cancer.

Given that the phenotype of CS patients is weighted toward terminally differentiated cells and tissues with limited replicative potential, we can extend our explanation further. Because terminally differentiated cells attenuate GGR (58), there is no “backup” pathway for the defective TCR of CS cells. As such, bulky lesions and unresolved R loops induce apoptosis via irreversible transcription block. The few replicative cells in these tissues undergo replicative exhaustion (59) from having to replace apoptotic cells more rapidly than in normal individuals, resulting in tissue senescence and contributing the neurodegeneration and progeria features seen in CS.

Mutation in hTERT Cells—Hormesis or Repair.

Normal (GM05659) and CS-B (GM01428) cells were transfected with hTERT by lentivirus (pBabePuro-hTERT) and maintained in continuous culture for more than 2 y. They maintained their relative UV sensitivities, the GM01428T line being much more UV sensitive than the GM05659T line (50% survival with doses of 4.0 J/m2 and 25.5 J/m2, respectively). These cells were assayed for mutations following UV irradiation using duplex sequencing with a capture set against the exomic regions of DNMT3a, IDH1, IDH2, TET2, NPM1, C/EBPa, PTPN11, c-KIT, BRAF, RUNX1, Hbb, NRAS, KRAS, TP53, WT1, U2AF1, and POLD1. The hTERT cells had very high levels of subclonal mutations that were at least an order of magnitude higher (Fig. S5A) than the frequency of new UV-induced mutations; consequently the new UV-induced mutations could not be detected (Figs. 2 and 3). Instead UV-induced killing caused a loss of subclonal diversity and normalization of clonal mutations to heterozygotes or homozygotes (50% clonality and 100% clonality, respectively), as is consistent with UV-induced selection of the culture (Fig. S5B). This loss may indicate that cells with preexisting mutations are more sensitive to the additional stress of UV damage. The reduction in subclonal diversity resulted in smaller populations with reduced variant frequencies, analogous to the bottleneck or sampling of the original populations that resulted in the reduction in genetic diversity associated with human population migration (60).

Immunohistochemistry analyses with a series of probes revealed that these cells were aneuploid and had increased copy numbers at several loci (Fig. S6). Other groups have previously observed similar genomic instability in hTERT+ cells grown for extensive periods of time (34–36).

Similar decreases in mutations in response to low-level radiation have been reported previously; this decrease is termed “hormesis” (61). Often the term has been used to imply that radiation elicits a repair process that mitigates the initial impact of radiation (61). The concept has even been extrapolated to imply that radiation standards should be set at levels to take advantage of a supposed health benefit of low radiation levels (61). Our studies have the advantage of distinguishing the mutations and genomic instability initially present in the population from the mutations induced by UV. Our observations clearly show that the observed reduction in mutations is a result of selection against cells with preexisting mutations (Fig. S5B) and is not the consequence of de novo repair and mutagenesis. If these results can be extended to studies with ionizing radiation, then the idea of a health benefit from low-level radiation needs to be reconsidered, because our results suggest that cells already carrying a significant load of preexisting mutations may be selectively vulnerable to further radiation-induced toxicity.

Methods

Work with human cells was approved by the University of California, San Francisco Committee on Human Research, inclusive of informed consent (IRB11-05993 to J.E.C.). Normal, XP-C, and CS-A and -B human fibroblasts were obtained from the Coriell Institute (Table S1). One XP-C culture (XP226BA) was derived from discarded tissue after cancer surgery of patients in Guatemala (45). The fibroblast culture NHF-D was a gift from D. Oh, University of California, San Francisco. A culture of pooled neonatal keratinocytes was developed in house. One normal (GM05659T) and one CS-B (GM01428T) culture was transfected with lentivirus expressing hTERT and was grown continuously for at least 2 y.

To measure survival, cells were grown for 48 h in 96-well plates, drained of medium, and then exposed to a range of doses of UVC (254 nm) or UVB (280–320 nm) using a battery of five fluorescent tubes for each wavelength. The UVB lamps were filtered to remove UVC. The plates were opaque to UVC, but additional shielding was used for UVB. Cells then were allowed to grow for 5–7 d and were harvested. Survival was measured colorimetrically with MTT (Sigma-Aldrich) at 570 nm. Relative survival was calculated from the ratios of exposed to unexposed wells, based on the average 570-nm absorbance in four to six wells per exposure condition. We chose to measure the survival at 5–7 d, which corresponded to the time of harvest for our mutagenesis analysis. The surviving cell numbers represent a combination of cell lysis, growth delays, and rates of regrowth.

To measure UV-induced mutagenesis, cultures of ∼107 cells were washed in PBS, irradiated, and grown for 5–7 d. Cells then were harvested by trypsin, washed in PBS, and rapidly frozen in dry ice/methanol. DNA was isolated, and mutations were measured by one round of duplex sequencing (18), as described more fully in the SI Methods. Target genes were exonic regions of NRAS, UMPS, PIK3CA, EGFR, BRAF, KRAS, F10, TP53, and TYMS, several of which were chosen for their importance in skin carcinogenesis (Table S2). We required a minimum depth of 100 duplex molecules to call a position, either mutant or not; all samples had a midexon peak depth of 1,000–4,000 duplex molecules across all captured exons.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Oh for the gift of NHF-D and D. Karentz of the University of San Francisco for advice and support. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants CA181771 and CA077852 (to L.A.L. and K.S.R.-B.); the Academic Senate of the University of California, San Francisco; and the Lily Drake Cancer Research Fund of the University of San Francisco (J.E.C.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1610020113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Cleaver JE, Lam ET, Revet I. Disorders of nucleotide excision repair: The genetic and molecular basis of heterogeneity. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(11):756–768. doi: 10.1038/nrg2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kraemer KH, Lee MM, Scotto J. DNA repair protects against cutaneous and internal neoplasia: Evidence from xeroderma pigmentosum. Carcinogenesis. 1984;5(4):511–514. doi: 10.1093/carcin/5.4.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradford PT, et al. Cancer and neurologic degeneration in xeroderma pigmentosum: Long term follow-up characterises the role of DNA repair. J Med Genet. 2011;48(3):168–176. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.083022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nance MA, Berry SA. Cockayne syndrome: Review of 140 cases. Am J Med Genet. 1992;42(1):68–84. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320420115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang WR, Garrett GL, Cleaver JE, Arron ST. Absence of skin cancer in the DNA repair-deficient disease Cockayne Syndrome (CS): A survey study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(6):1270–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lehmann AR. Cockayne syndrome and trichothiodystrophy: Defective repair without cancer. Cancer Reviews. 1987;7:82–103. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson DM, 3rd, Bohr VA. Special issue on the segmental progeria Cockayne syndrome. Mech Ageing Dev. 2013;134(5-6):159–160. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kubota M, et al. Nationwide survey of Cockayne syndrome in Japan: Incidence, clinical course and prognosis. Pediatr Int. 2015;57(3):339–347. doi: 10.1111/ped.12635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loeb LA. Mutator phenotype may be required for multistage carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1991;51(12):3075–3079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martincorena I, et al. Tumor evolution. High burden and pervasive positive selection of somatic mutations in normal human skin. Science. 2015;348(6237):880–886. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa6806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maher VM, Dorney DJ, Mendrala AL, Konze-Thomas B, McCormick JJ. DNA excision-repair processes in human cells can eliminate the cytotoxic and mutagenic consequences of ultraviolet irradiation. Mutat Res. 1979;62(2):311–323. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(79)90087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maher VM, Ouellette LM, Curren RD, McCormick JJ. Frequency of ultraviolet light-induced mutations is higher in xeroderma pigmentosum variant cells than in normal human cells. Nature. 1976;261(5561):593–595. doi: 10.1038/261593a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin YW, et al. Somatic cell mutation frequency at the HPRT, T-cell antigen receptor and glycophorin A loci in Cockayne syndrome. Mutat Res. 1995;337(1):49–55. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(95)00014-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parris CN, Kraemer KH. Ultraviolet-induced mutations in Cockayne syndrome cells are primarily caused by cyclobutane dimer photoproducts while repair of other photoproducts is normal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90(15):7260–7264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muriel WJ, Lamb JR, Lehmann AR. UV mutation spectra in cell lines from patients with Cockayne’s syndrome and ataxia telangiectasia, using the shuttle vector pZ189. Mutat Res. 1991;254(2):119–123. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(91)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox EJ, Reid-Bayliss KS, Emond MJ, Loeb LA. Accuracy of Next Generation Sequencing Platforms. Next Gener Seq Appl. 2014;1:1000106. doi: 10.4172/jngsa.1000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmitt MW, et al. Detection of ultra-rare mutations by next-generation sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(36):14508–14513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208715109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennedy SR, et al. Detecting ultralow-frequency mutations by Duplex Sequencing. Nat Protoc. 2014;9(11):2586–2606. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller JH. Mutagenic specificity of ultraviolet light. J Mol Biol. 1985;182(1):45–65. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brash DE. UV signature mutations. Photochem Photobiol. 2015;91(1):15–26. doi: 10.1111/php.12377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aamann MD, Muftuoglu M, Bohr VA, Stevnsner T. Multiple interaction partners for Cockayne syndrome proteins: Implications for genome and transcriptome maintenance. Mech Ageing Dev. 2013;134(5-6):212–224. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spivak G, Hanawalt PC. Host cell reactivation of plasmids containing oxidative DNA lesions is defective in Cockayne syndrome but normal in UV-sensitive syndrome fibroblasts. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5(1):13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D’Errico M, et al. The role of CSA in the response to oxidative DNA damage in human cells. Oncogene. 2007;26(30):4336–4343. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kielbassa C, Roza L, Epe B. Wavelength dependence of oxidative DNA damage induced by UV and visible light. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18(4):811–816. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.4.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuluncsics Z, Perdiz D, Brulay E, Muel B, Sage E. Wavelength dependence of ultraviolet-induced DNA damage distribution: Involvement of direct or indirect mechanisms and possible artefacts. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1999;49(1):71–80. doi: 10.1016/S1011-1344(99)00034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang X, Rosenstein BS, Wang Y, Lebwohl M, Wei H. Identification of possible reactive oxygen species involved in ultraviolet radiation-induced oxidative DNA damage. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997;23(7):980–985. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoeijmakers JH. Genome maintenance mechanisms for preventing cancer. Nature. 2001;411(6835):366–374. doi: 10.1038/35077232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pasquier L, et al. Wide clinical variability among 13 new Cockayne syndrome cases confirmed by biochemical assays. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91(2):178–182. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.080473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng KC, Cahill DS, Kasai H, Nishimura S, Loeb LA. 8-Hydroxyguanine, an abundant form of oxidative DNA damage, causes G----T and A----C substitutions. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(1):166–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shigenaga MK, Gimeno CJ, Ames BN. Urinary 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine as a biological marker of in vivo oxidative DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86(24):9697–9701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.24.9697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gajewski E, Rao G, Nackerdien Z, Dizdaroglu M. Modification of DNA bases in mammalian chromatin by radiation-generated free radicals. Biochemistry. 1990;29(34):7876–7882. doi: 10.1021/bi00486a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang XR, et al. Telomerase expression in human somatic cells does not induce changes associated with a transformed phenotype. Nat Genet. 1999;21(1):111–114. doi: 10.1038/5056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morales CP, et al. Absence of cancer-associated changes in human fibroblasts immortalized with telomerase. Nat Genet. 1999;21(1):115–118. doi: 10.1038/5063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Milyavsky M, et al. Prolonged culture of telomerase-immortalized human fibroblasts leads to a premalignant phenotype. Cancer Res. 2003;63(21):7147–7157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Waarde-Verhagen MA, Kampinga HH, Linskens MH. Continuous growth of telomerase-immortalised fibroblasts: How long do cells remain normal? Mech Ageing Dev. 2006;127(1):85–87. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacKenzie KL, Franco S, May C, Sadelain M, Moore MA. Mass cultured human fibroblasts overexpressing hTERT encounter a growth crisis following an extended period of proliferation. Exp Cell Res. 2000;259(2):336–350. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee DH, Pfeifer GP. Translesion synthesis of 7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-2′-deoxyguanosine by DNA polymerase eta in vivo. Mutat Res. 2008;641(1-2):19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cleaver JE, et al. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species are scavenged by Cockayne syndrome B protein in human fibroblasts without nuclear DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(37):13487–13492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414135111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Washington MT, Johnson RE, Prakash S, Prakash L. Fidelity and processivity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase eta. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(52):36835–36838. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.36835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Washington MT, Johnson RE, Prakash L, Prakash S. The mechanism of nucleotide incorporation by human DNA polymerase eta differs from that of the yeast enzyme. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(22):8316–8322. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.22.8316-8322.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang M, et al. Roles of E. coli DNA polymerases IV and V in lesion-targeted and untargeted SOS mutagenesis. Nature. 2000;404(6781):1014–1018. doi: 10.1038/35010020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rapin I, et al. Cockayne syndrome in adults: Review with clinical and pathologic study of a new case. J Child Neurol. 2006;21(11):991–1006. doi: 10.1177/08830738060210110101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Armstrong BK, Kricker A. The epidemiology of UV induced skin cancer. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2001;63(1-3):8–18. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(01)00198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferrucci LM, et al. Indoor tanning and risk of early-onset basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(4):552–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.11.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cleaver JE, Feeney L, Tang JY, Tuttle P. Xeroderma pigmentosum group C in an isolated region of Guatemala. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127(2):493–496. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ridley AJ, Colley J, Wynford-Thomas D, Jones CJ. Characterisation of novel mutations in Cockayne syndrome type A and xeroderma pigmentosum group C subjects. J Hum Genet. 2005;50(3):151–154. doi: 10.1007/s10038-004-0228-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jaspers NG, et al. Anti-tumour compounds illudin S and Irofulven induce DNA lesions ignored by global repair and exclusively processed by transcription- and replication-coupled repair pathways. DNA Repair (Amst) 2002;1(12):1027–1038. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00166-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(14):1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brash DE, et al. The DNA damage signal for Mdm2 regulation, Trp53 induction, and sunburn cell formation in vivo originates from actively transcribed genes. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117(5):1234–1240. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lehmann AR, Kirk-Bell S, Mayne L. Abnormal kinetics of DNA synthesis in ultraviolet light-irradiated cells from patients with Cockayne’s syndrome. Cancer Res. 1979;39(10):4237–4241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cleaver JE. Normal reconstruction of DNA supercoiling and chromatin structure in cockayne syndrome cells during repair of damage from ultraviolet light. Am J Hum Genet. 1982;34(4):566–575. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McKay BC, Becerril C, Spronck JC, Ljungman M. Ultraviolet light-induced apoptosis is associated with S-phase in primary human fibroblasts. DNA Repair (Amst) 2002;1(10):811–820. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00109-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carvalho H, et al. Effect of cell confluence on ultraviolet light apoptotic responses in DNA repair deficient cells. Mutat Res. 2003;544(2-3):159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2003.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tresini M, et al. The core spliceosome as target and effector of non-canonical ATM signalling. Nature. 2015;523(7558):53–58. doi: 10.1038/nature14512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hamdi M, et al. DNA damage in transcribed genes induces apoptosis via the JNK pathway and the JNK-phosphatase MKP-1. Oncogene. 2005;24(48):7135–7144. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sollier J, et al. Transcription-coupled nucleotide excision repair factors promote R-loop-induced genome instability. Mol Cell. 2014;56(6):777–785. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bowden NA, Beveridge NJ, Ashton KA, Baines KJ, Scott RJ. Understanding xeroderma pigmentosum complementation groups using gene expression profiling after UV-light exposure. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(7):15985–15996. doi: 10.3390/ijms160715985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nouspikel T, Hanawalt PC. Terminally differentiated human neurons repair transcribed genes but display attenuated global DNA repair and modulation of repair gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(5):1562–1570. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1562-1570.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hayflick L. The limited in vitro lifetime of human diploid cell strains. Exp Cell Res. 1965;37:614–636. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(65)90211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Henn BM, Cavalli-Sforza LL, Feldman MW. The great human expansion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(44):17758–17764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212380109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Calabrese EJ, Shamoun DY, Hanekamp JC. Cancer risk assessment: Optimizing human health through linear dose-response models. Food Chem Toxicol. 2015;81:137–140. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2015.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]