Abstract

Optimization of isoquinolinone PI3K inhibitors led to the discovery of a potent inhibitor of PI3K-γ (26 or IPI-549) with >100-fold selectivity over other lipid and protein kinases. IPI-549 demonstrates favorable pharmacokinetic properties and robust inhibition of PI3K-γ mediated neutrophil migration in vivo and is currently in Phase 1 clinical evaluation in subjects with advanced solid tumors.

Keywords: IPI-549, PI3K-gamma inhibitor, phosphoinositide-3-kinase, isoform selectivity, neutrophil migration, immuno-oncology

Phosphoinositide-3-kinases (PI3Ks) belong to a family of signal transducing enzymes that mediate key cellular functions in cancer and immunity. The primary role of these lipid kinases entails catalysis of the phosphorylation of the inositol ring of membrane phosphoinositides, which then serve as sites for the activation of secondary messengers involved in the regulation of multiple biological processes, including cell growth, survival, differentiation, proliferation, and migration. PI3Ks are divided into three classes (I, II, and III) based on substrate specificity, sequence homology, and types of regulatory subunits. Class I PI3Ks are further divided into two groups: Class IA, which includes PI3K-α, β, and δ, and Class IB, which contains only one member, PI3K-gamma (γ). While Class IA PI3Ks are predominantly activated by receptor tyrosine kinase signaling, PI3K-γ is activated primarily by G-protein coupled receptors.1−6

The PI3K-γ isoform is expressed in immune cells and has limited, if any, expression in normal or malignant epithelial cells and connective tissue cells.7 Studies of PI3K-γ knockout mice show that PI3K-γ is important for cellular activation and migration in response to certain chemokines.7,8 PI3K-γ signaling is particularly important for the function of myeloid cells, where it is downstream of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) (e.g., chemokine receptors) and RAS.7−9 In addition, PI3K-γ can be activated in response to tissue hypoxia in these cells.10 A critical role for PI3K-γ in the unique myeloid-derived cells that constitute a key component of the immune-suppressive tumor microenvironment has also been demonstrated in PI3K-γ deletion and kinase-dead knock-in studies. For example, murine syngeneic tumors grow slower when transplanted into immune-competent mice where PI3K-γ is genetically inactivated.9,10 This growth reduction is due to the abrogation of tumor-associated myeloid cells that are known to promote an immune-suppressive tumor microenvironment that permits tumor growth.9−12 In addition, tumor-associated myeloid cells are postulated to support tumor regrowth after radiation or chemotherapy, and to enable metastatic spread.13 These preclinical studies highlight a critical role for PI3K-γ in myeloid cell biology and suggest that PI3K-γ inhibition in tumor-associated myeloid cells may be effective at preventing tumor growth in a variety of settings.

To test the hypothesis that pharmacological inhibition of PI3K-γ in tumor-associated myeloid cells could block their immune-suppressive function and lead to enhanced immune attack on tumor cells, a potent and selective synthetic small-molecule inhibitor of the PI3K-γ isoform was needed. Although inhibitors of PI3K-γ have been reported over the past decade, their selectivity for PI3K-γ over other PI3K isoforms or pharmacologic properties were until recently not suitable for assessment of inhibiting only PI3K-γ in vivo.14−23 Hence, we set out to identify potent and selective inhibitors of PI3K-γ with desirable drug-like properties.

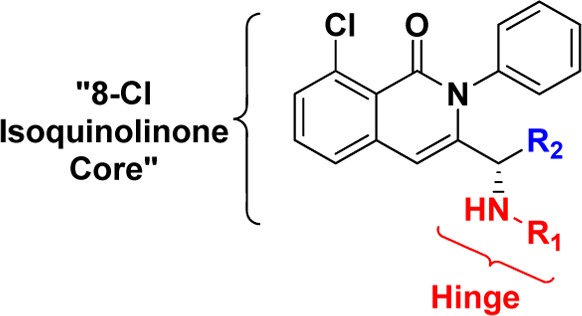

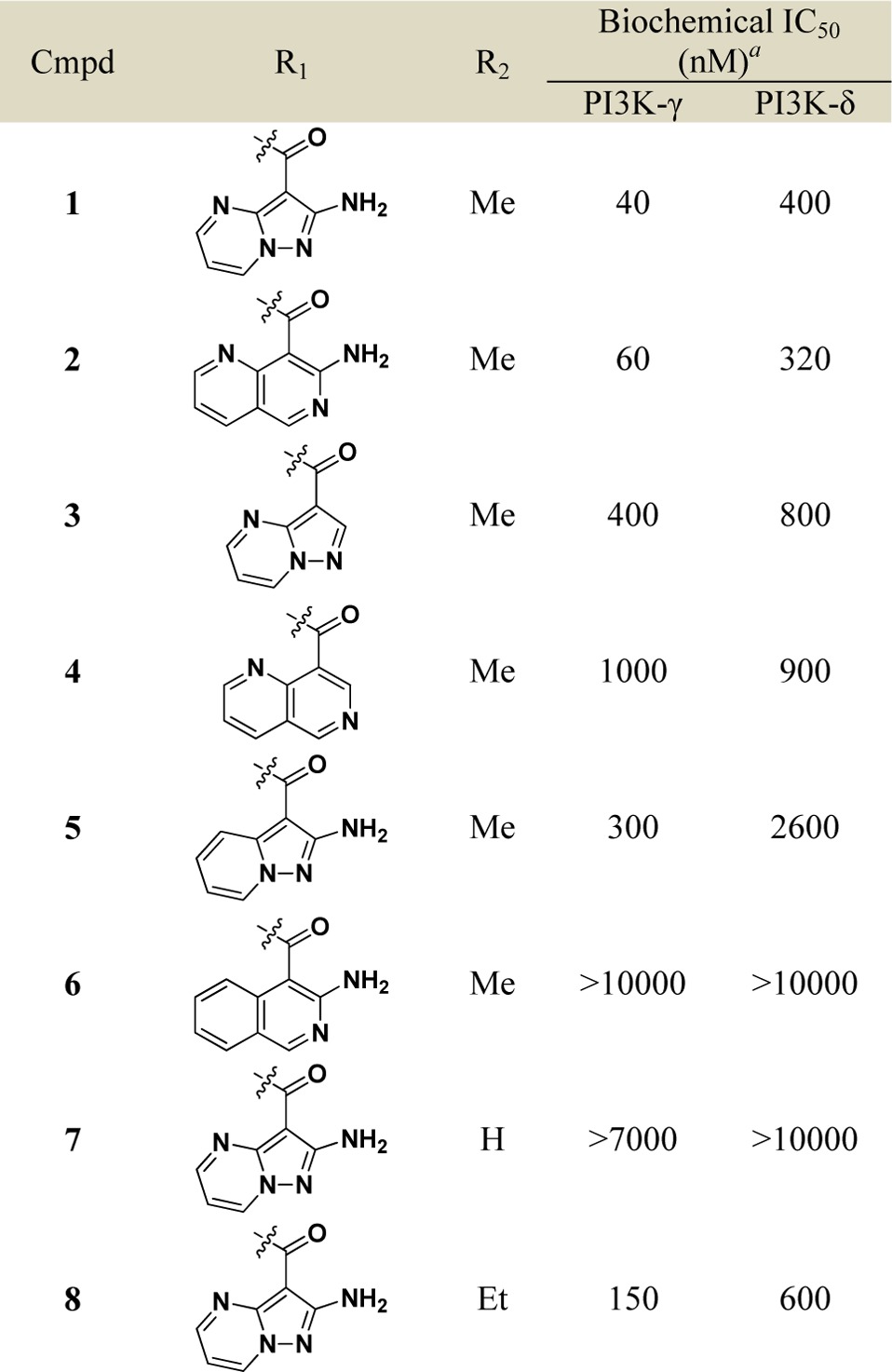

The N-phenyl 8-chloroisoquinolinone motif served as a possible scaffold to explore alternative hinge binding motifs that may provide unique interactions with PI3K-γ.24 To this end, we assembled a focused collection of 8-chloroisoquinolinone analogues that could be readily synthesized having hinge binding motifs containing at least one hydrogen bond acceptor and 0–2 hydrogen bond donors. We screened this focused collection for their ability to inhibit PI3K-γ and PI3K-δ at physiological ATP concentrations (3 mM) and were pleasantly surprised to see that compounds 1 and 2 showed moderate selectivity for PI3K-γ over PI3K-δ (Table 1).

Table 1. Structure–Activity Relationship from Hinge (R1) and Linker Modifications (R2).

Data reported as the average of at least two runs. See Supporting Information for description of assay conditions and SEM values.

The hinge binding motifs on compounds 1 and 2 shared the following common features: an amide bond to isoquinolinone core with a chiral linker, an exocyclic amine as part of a hydrogen bond donor/acceptor pair, and a heterocyclic nitrogen oriented toward the core. The importance of these structural features on potency and selectivity was confirmed by a set of direct analogues of 1 and 2 (Table 1). Analogues without the exocyclic amine (3 and 4) were significantly less potent and selective than 1 and 2, respectively. The carbo-analogue of the 6–5 bicyclic system (5) was less active than the aza-analogue (1), whereas the same modification on the 6–6 bicyclic system (6 vs 2) rendered the compound largely inactive against both PI3K isoforms. These data suggest that the dihedral angle between the carbonyl amide and the heterocyclic hinge binding motifs 1 and 2 provides a preferred conformation for binding to both PI3K-γ and PI3K-δ. Changes to the chiral linker between the hinge binding motif and N-phenyl 8-chloroisoquinolinone core also proved to be deleterious to PI3K potency and selectivity. The enantiomer of 1 and the des-methyl achiral analogue 7 were largely inactive against both PI3K isoforms. Interestingly, the selectivity was reduced when the chiral methyl is extended to an ethyl substituent (8 vs 1). These data highlight key hydrogen bonding features on the hinge binding motifs and the preferred chiral linker of N-phenyl 8-chloroisoquinolinones 1 and 2 that make them bona fide leads for the development of selective PI3K-γ inhibitors.

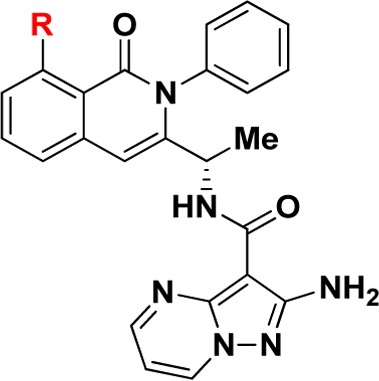

We evaluated leads 1 and 2 for selectivity across other PI3K isoforms and found 1 to be remarkably selective across other Class I and Class II PI3K isoforms (Table S1). Therefore, we focused our attention on further optimization of compound 1. Taking the published cocrystal structures of propeller-shaped ligand PIK-39 with PI3K-δ and PI3K-γ into consideration, we evaluated C8 substitution on compound 1 to access a nonconserved region within PI3Ks with the aim of improving the PI3K-γ potency and selectivity (Table 2).25,26 We found small C8 substitutions such as methyl (9) and fluoro (10) did not have a profound impact on PI3K-γ potency or selectivity. However, a significant loss in PI3K-γ potency was seen with an electron-withdrawing cyano group (11) or electron-donating groups (12–14) at the 8 position. Vinyl substitution at the 8 position (15) also had a negative impact on PI3K-γ potency. However, 8-alkyne substitutions (16 and 17) unexpectedly provided modest improvements in potency for PI3K-γ over the 8-chloro substitution in 1. Importantly, the methyl alkyne analogue 17 also demonstrated weaker activity against PI3K-δ compared to 1 and 16, and thus, 17 had >40-fold selectivity for PI3K-γ over PI3K-δ, suggesting that the alkyne substitution makes significant nonfavorable interactions with PI3K-δ at the nonconserved residues adjacent to the specificity pocket (Lys802 for PI3K-γ versus Thr750 for PI3K-δ) as does the aminopyrazolopyrimidine at the hinge binding region21,22 (see Supporting Information, Figure S1).

Table 2. Structure–Activity Relationship of C8 Substitution.

Data reported as the average of at least two runs.

n = 1. See Supporting Information for description of assay conditions and SEM values.

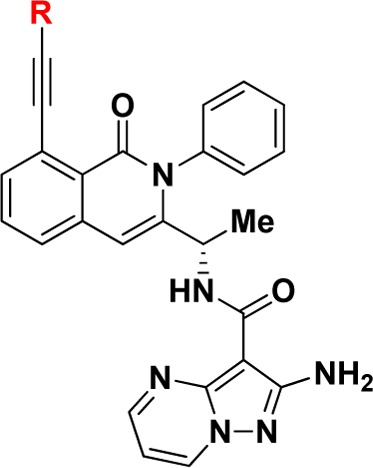

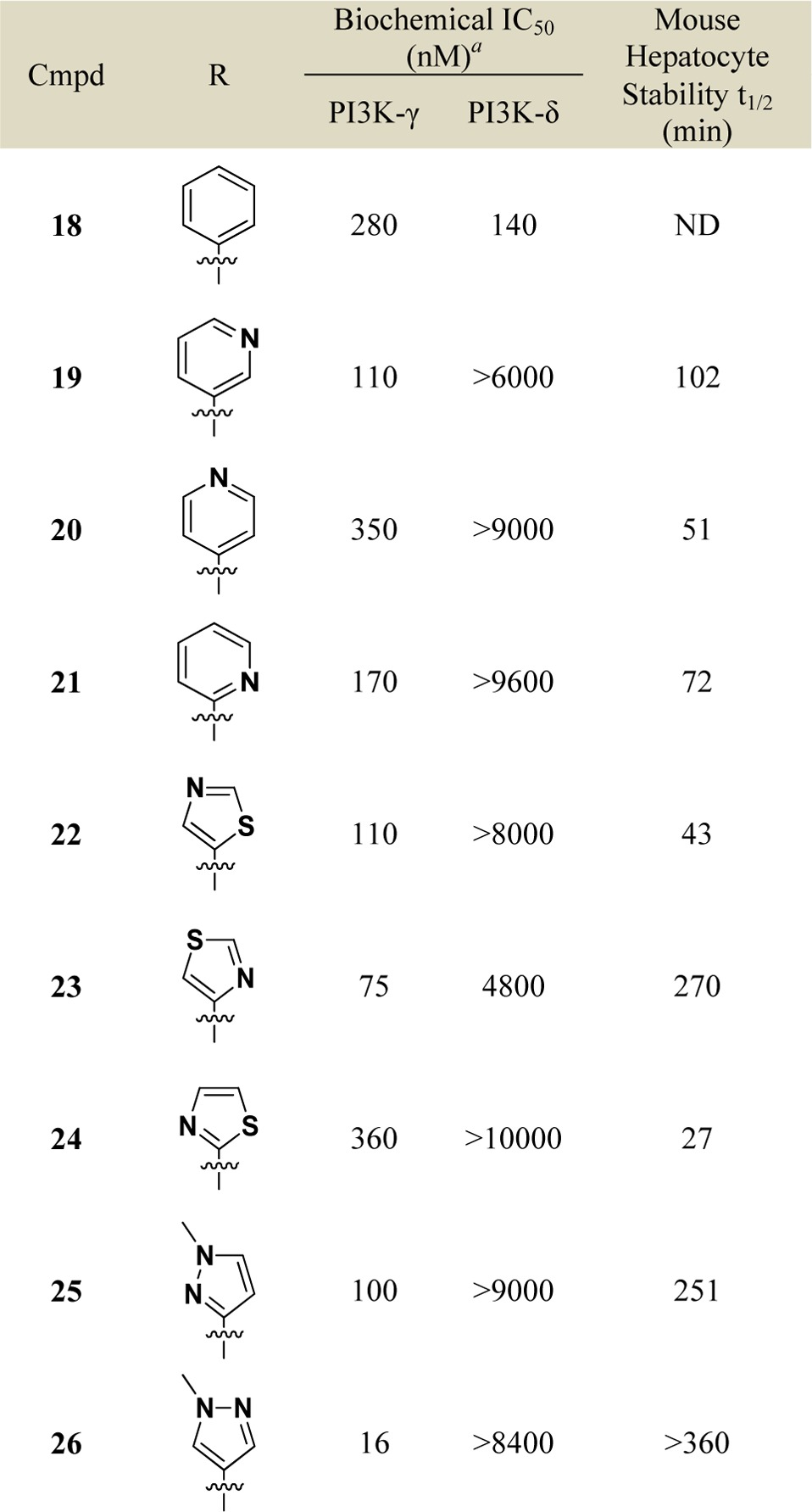

Various substituted alkyne analogues at the 8-position that extended further into the nonconserved pocket were then prepared and evaluated for PI3K-γ potency and selectivity (Table 3). Additionally, as alkyl substituted alkyne analogues 16 and 17 suffered from poor in vitro metabolic stability, we also screened these substituted alkyne analogues for improved stability in mouse hepatocytes. Interestingly, hydrophobic substituents that extended deeper into the pocket (e.g., phenyl analogue 18 vs methyl analogue 17) were found to have eroded PI3K-γ potency and selectivity. Less hydrophobic groups (e.g., pyridyl analogues 19–21) maintained good selectivity for PI3K-γ and were found to be more metabolically stable than methyl alkyne analogue 17. With this in mind, we synthesized and evaluated various analogues with smaller heterocycles on the end of the 8-alkyne (e.g., 22–26). Among various 5-membered ring heterocycle analogues, N-methylpyrazole analogue 26 proved to have excellent potency and selectivity for PI3K-γ over PI3K-δ in enzymatic assays and excellent in vitro metabolic stability. Having achieved this remarkable selectivity in biochemical assays and in vitro metabolic stability, we further profiled compound 26 in various in vitro and in vivo settings.

Table 3. Structure–Activity Relationship of C-8 Alkynyl Substitution.

Data reported as the average of at least two runs. See Supporting Information for description of assay conditions and SEM values.

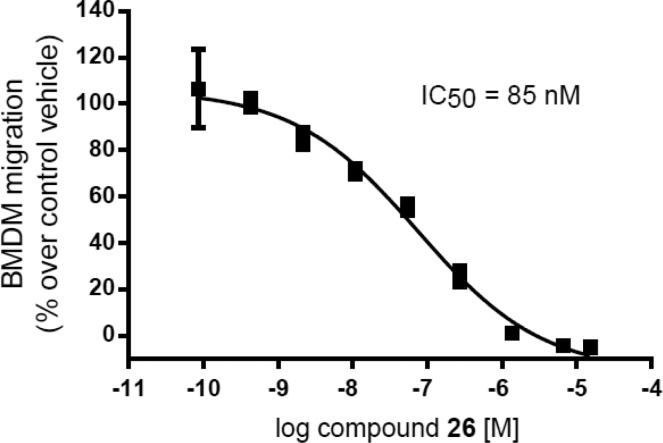

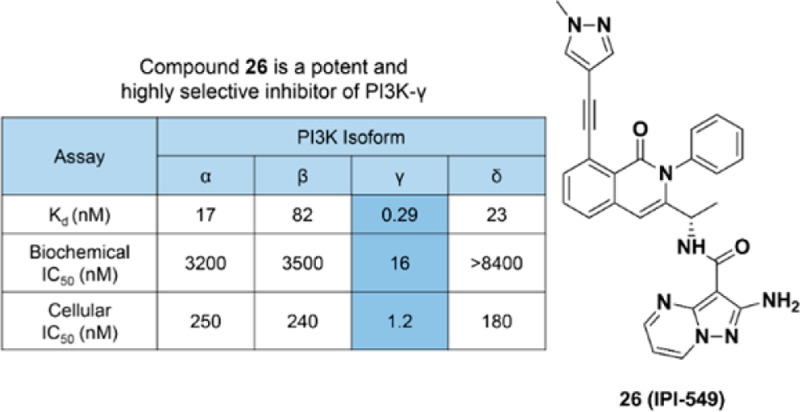

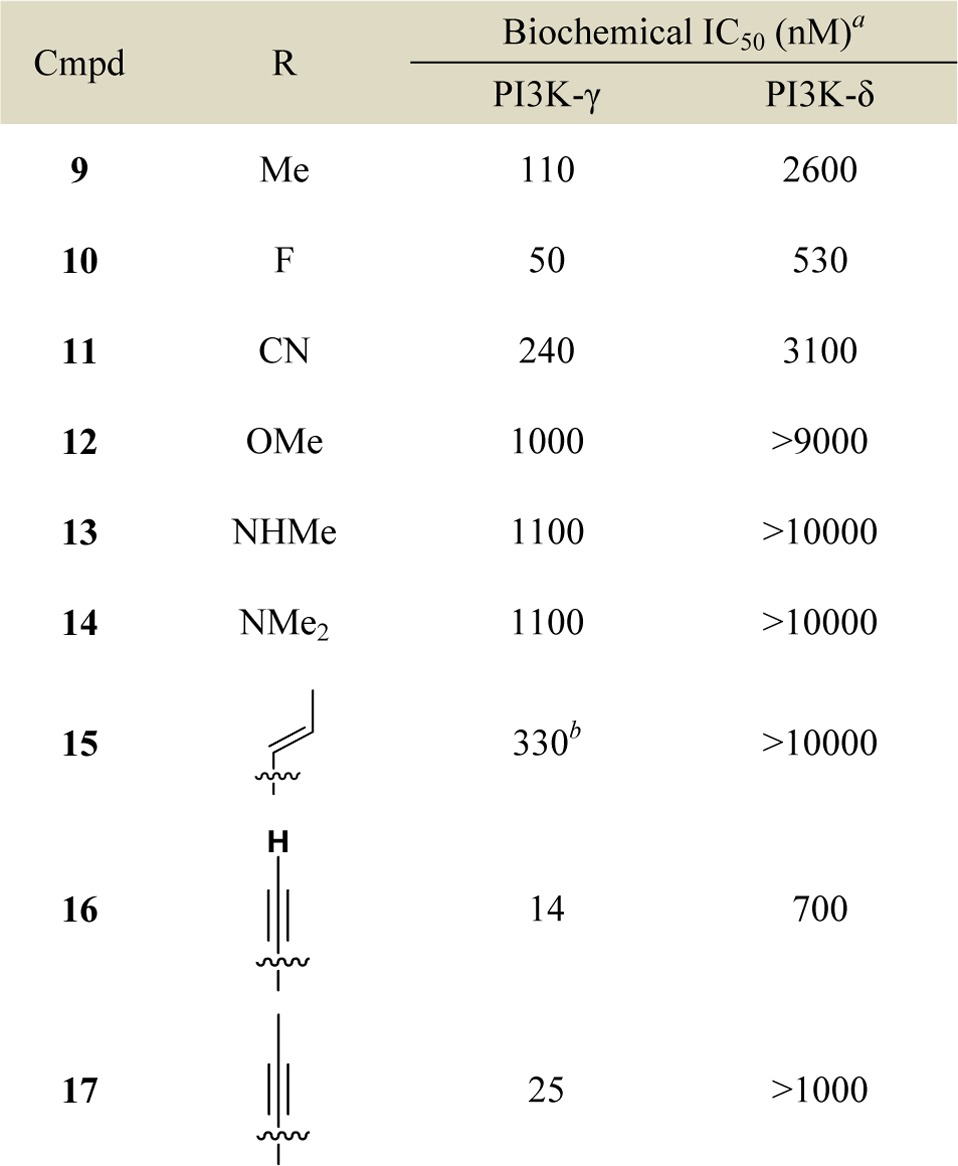

Compound 26 was evaluated for activity across all Class I PI3K isoforms. The binding affinity of compound 26 for PI3K-γ was determined by measuring the individual rates constants (koff and kon) and for PI3K-α, β, and δ using equilibrium fluorescent titration. Compound 26 was found to be a remarkably tight binder to PI3K-γ with a Kd of 290 pM and >58-fold weaker affinity for other Class I PI3K isoforms (Table 4). Additionally, compound 26 did not significantly inhibit a panel of 468 mutant and nonmutant protein and lipid kinases (including Class II PI3K isoforms) at 1 μM (Tables S1 and S4). In PI3K-α, -β, -γ, and -δ dependent cellular phospho-AKT assays, compound 26 demonstrated excellent PI3K-γ potency (IC50 = 1.2 nM) and selectivity against other Class I PI3K isoforms (>146-fold). Furthermore, compound 26 dose dependently inhibited PI3K-γ-dependent bone marrow-derived macrophage (BMDM) migration in vitro (Figure 1).27

Table 4. Class I PI3K Selectivity Profile for Compound 26 in Biochemical and Cellular Assays.

| PI3K

isoform |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| assay | α | β | γ | δ |

| Kd (nM)a | 17 | 82 | 0.29 | 23 |

| biochemical IC50 (nM) | 3200 | 3500 | 16 | >8400 |

| cellular IC50 (nM)b | 250 | 240 | 1.2 | 180 |

Binding affinities (Kd) of 26 were determined by methods previously reported.24 See Supporting Information for full details.

Cellular IC50s for Class I PI3K-α, PI3K-β, PI3K-γ, and PI3K-δ were determined in SKOV-3, 786-O, RAW 264.7, and RAJI cells, respectively, by monitoring inhibition of pAKT S473 by ELISA.

Figure 1.

Effect of compound 26 on migration of bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) in vitro. BMDMs were stimulated to migrate toward 100 μg/mL CXCL12 (SDF-1α) for 3 h through a 5 μm Boyden Chamber with or without DMSO or a dose response of compound 26. Migrated BMDMs were counted and compared to control.

Compound 26 was also found to be selective against a panel of 80 GPCRs, ion channels, and transporters at 10 μM (see Supporting Information, Table S5 for full selectivity details). Additional in vitro safety assessment of compound 26 demonstrated that it was negative in Ames mutagenicity assays and had an IC50 greater than 10 μM in a hERG binding assay (data not shown).

In vitro absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties and pharmacokinetic parameters of compound 26 were also determined (summarized in Table 5). In vitro, 26 showed moderate to high cell permeability across Caco-2 cell monolayers, was slowly metabolized in cultured hepatocytes (t1/2 > 360 min), and demonstrated IC50s greater than 20 μM for the CYP isoforms tested (1A2, 2B6, 2C8, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 3A4). In vivo (mice, rats, dog, and monkeys), compound 26 had excellent oral bioavailability, low clearance, and distributed into tissues with a mean volume of distribution of 1.2 L/kg (Table 5). Overall, compound 26 had a favorable pharmacokinetic profile to allow potent and selective inhibition of PI3K-γ in vivo.

Table 5. In Vitro ADME and Pharmacokinetics for Compound 26.

| in vitro ADME | |

|---|---|

| Caco-2 (Papp 10–6 cm/sec; A to B @ 10 μM) | 13 |

| PPB (% free; mouse, rat, dog, monkey, human @ 1 μM) | 2.2, 2.8, 2.8, 4.0, 1.1 |

| metabolic stability (t1/2; min)a | >360 |

| CYP3A4 inhibition (IC50; μM) | >20 |

| pharmacokinetics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mouse | rat | dog | monkey | |

| Cmax (μM)b | 3.6 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 0.56 |

| AUC0-∞ (ng·h/mL)b | 20568 | 8049 | 1066 | 4030 |

| t1/2 (h)c | 3.2 | 4.4 | 6.7 | 4.3 |

| CL (mL/min/kg)c | 3.6 | 4.4 | 2.8 | 4.3 |

| Vss (L/kg)c | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| %F | 88 | 57 | 65 | 31 |

Study conducted using cultured human hepatocytes.

Determined from oral dosing to male animals. PO dose levels: 5 mg/kg mouse and rat, 2.5 mg/kg monkey and dog. Formulation: 0.5% carboxymethylcellulose, 0.05% Tween 80.

Determined from intravenous dosing to male animals. IV dose levels: 1 mg/kg mouse and rat, 0.5 mg/kg monkey and dog. Formulation: 5% NMP, 40% PEG400, 55% PBS.

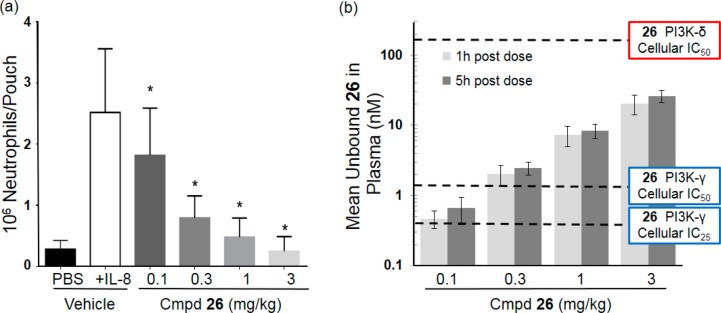

Based on the pharmacokinetic properties in mice and pharmacological in vitro profile, compound 26 was well-suited to investigate the impact of potent and selective PI3K-γ inhibition in vivo. IL-8 stimulated neutrophil migration into air pouches in mice has previously been shown to be dependent on PI3K-γ. Thus, to demonstrate PI3K-γ dependent activity of compound 26 in vivo, we evaluated the effect of orally administered compound 26 on IL-8 stimulated neutrophil influx into the air pouches on mice.7,8 Compound 26 significantly reduced neutrophil migration in a dose-dependent manner in this model when administered orally at all of the tested doses (Figure 2a). The degree of inhibition observed directly correlated with plasma concentrations of compound 26 in these mice (Figure 2b) clearly demonstrated that orally administered compound 26 can inhibit PI3K-γ function in vivo. In addition, compound 26 (IPI-549) has been shown to inhibit tumor growth in murine syngeneic models through alteration of immune cells in the tumor microenvironment.28

Figure 2.

(a) Effect of compound 26 on neutrophil migration in the mouse air pouch model. Mice were dosed orally 1 h before IL-8 was applied to the air pouch. After 4 h the air pouch was lavaged and the neutrophils counted using a CELL-DYN hematology analyzer. *p values < 0.05 compared to vehicle. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean of 10 mice per group. (b) Plasma concentration levels of compound 26 at 1 and 5 h postadministration with overlaying cellular IC50 (PI3K-γ and PI3K-δ) and IC25 (PI3K-γ) values.

On the basis of its remarkable PI3K-γ potency and selectivity, favorable in vitro safety and pharmacokinetic profiles, and ability to inhibit PI3K-γ in vivo, compound 26 (IPI-549) was chosen as a development candidate. IPI-549 is currently in Phase 1 clinical evaluation in subjects with advanced solid tumors.29

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Nicole Hurst for coordinating the preclinical safety evaluation of IPI-549, Dan Snyder and Amael Madec for assistance in preparation of early analogues, Drs. Jeff Kutok and Karen McGovern for guidance on the pharmacological assessment of IPI-549, and colleagues at Intellikine, Drs. Pingda Ren and Liansheng Li, for their insights on PI3K inhibitors.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- ADME

absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion

- AKT

protein kinase B

- ADP

adenosine diphosphate

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- BMDMs

bone marrow-derived macrophages

- CXCL12

chemokine C-X-C motif 12

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- DMSO

dimethysulfoxide

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- GPCR

G-protein-coupled receptor

- IL-8

interleukin 8

- NMP

N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PPB

plasma protein binding

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- SDF-1

stromal cell-derived factor 1

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00238.

Synthetic procedures and analytical data for 1–26; PI3K biochemical and cellular assay conditions; PI3K Class I and II selectivity data for 1 and 2; full selectivity data for 26; general animal study protocols (PDF)

Author Present Address

† Blueprint Medicines, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, United States.

Author Present Address

‡ AbbVie, North Chicago, Illinois 60064, United States.

Author Present Address

§ Surface Oncology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02142, United States.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Cantley L. C. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science 2002, 296, 1655–1657. 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhaesebroeck B.; Whitehead M. A.; Pineiro R. Molecules in medicine mini-review: isoforms of PI3K in biology and disease. J. Mol. Med. 2016, 94, 5–11. 10.1007/s00109-015-1352-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins P. T.; Stephens L. R. PI3K signaling in inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2015, 1851, 882–897. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe L. M.; Yuzugullu H.; Zhao J. J. PI3K in cancer: divergent roles of isoforms, modes of activation and therapeutic targeting. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 7–24. 10.1038/nrc3860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rommel C.; Camps M.; Ji H. PI3Kδ and PI3Kγ: partners in crime in inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis and beyond?. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 7, 191–201. 10.1038/nri2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banham-Hall E.; Clatworthy M. R.; Okkenhaug K. The therapeutic potential for PI3K inhibitors in autoimmune and rheumatic diseases. Open Rheumatol. J. 2012, 6, 245–258. 10.2174/1874312901206010245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T.; Irie-Sasaki U.; Jones R. G.; Oliveira-do-Santos A. J.; Stanford W. L.; Bolon B.; Wakeham A.; Itie A.; Bouchard D.; Kozieradzki I.; Joza N.; Mak T. W.; Ohashi P. S.; Suzuki A.; Penninger J. M. Function of PI3Kγ in thymocyte development, T cell activation, and neutrophil migration. Science 2000, 287, 1040–1046. 10.1126/science.287.5455.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch E.; Katanaev V. L.; Garlanda C.; Azzolino O.; Pirola L.; Silengo L.; Sozani S.; Mantovani A.; Altruda F.; Wymann M. P. Central role for G protein-coupled phosphoinositide 3-kinase in inflammation. Science 2000, 287, 1049–1053. 10.1126/science.287.5455.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid M. C.; Avraamides C. J.; Dippold H. C.; Franco I.; Foubert P.; Ellies L. G.; Acevedo L. M.; Manglicmot J. R. E.; Song X.; Wrasidlo W.; Blair S. L.; Ginsberg M. H.; Cheresh D. A.; Hirsch E.; Field S. J.; Varner J. A. Receptor tyrosine kinases and TLR/IL1Rs unexpectedly activate myeloid cell PI3K γ, a single convergent point promoting tumor inflammation and progression. Cancer Cell 2011, 19, 715–727. 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi S.; Singh A. R.; Zulcic M.; Durden D. L. A macrophage-dominant PI3K isoform controls hypoxia-induced HIF1alpha and HIF2alpha stability and tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2014, 12, 1520–1531. 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson A. J.; Kaneda M. M.; Tsujikawa T.; Nguygen A. V.; Affara N. I.; Ruffell B.; Gorjestani S.; Liudahl S. M.; Truitt M.; Olson P.; Kim G.; Hanahan D.; Tempero M. A.; Sheppard B.; Irving B.; Chang B. Y.; Varner J. A.; Coussens L. M. Bruton tryrosine kinase-dependent immune cell cross-talk drives pancreas cancer. Cancer Discovery 2016, 6, 270–285. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera L. B.; Meyronet D.; Hervieu V.; Frederick M. J.; Bergsland E.; Bergers G. Intratumoral myeloid cells regulate responsiveness and resistance to antiangiogenic therapy. Cell Rep. 2015, 11, 577–591. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Palma M.; Lewis C. E. Macrophage regulation of tumor responses to anticancer therapies. Cancer Cell 2013, 23, 277–286. 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushing T. D.; Metz D. P.; Whittington D. A.; McGee L. R. PI3Kδ and PI3Kγ as targets for autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 8559–8581. 10.1021/jm300847w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergamini G.; Bell K.; Shimamura s.; Werner T.; Cansfield A.; Mueller K.; Perrin J.; Tau C.; Ellard K.; Hopf C.; Doce C.; Leggate D.; Mangano R.; Mathieson T.; O’Mahony A.; Plavec I.; Rharbaoui F.; Savitski M. M.; Ramsden N.; Hirsch E.; Drewes G.; Rausch O.; Bantscheff M.; Neubauer G. A selective inhibitor reveals PI3Kγ dependence of TH17 cell differentiation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012, 8, 576–582. 10.1038/nchembio.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunose M.; Bell K.; Ellard K.; Bergamini G.; Neubauer G.; Werner T.; Ramsden N. Discovery of 5-(2-amino-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyridin-7-yl)-N-(tert-butyl)pyridine-3-sulfonamide (CZC24758), as a potent, orally bioavailable and selective inhibitor of PI3K for the treatment of inflammatory disease. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 4613–4618. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.05.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leahy J. W.; Buhr C. A.; Johnson H. W. B.; Kim B. G.; Baik T.; Cannoy J.; Forsyth T. P.; Jeong J. W.; Lee M. S.; Ma S.; Noson K.; Wang L.; Williams M.; Nuss J. M.; Brooks E.; Foster P.; Goon L.; Heald N.; Holst C.; Jaeger C.; Lam S.; Lougheed J.; Nguyen L.; Plonowski A.; Song J.; Stout T.; Wu X.; Yakes M. F.; Yu P.; Zhang W.; Lamb P.; Raeber O. Discovery of a novel series of potent and orally bioavailable phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 5467–5482. 10.1021/jm300403a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roller A.; Perino A.; Dapavo P.; Soro E.; Okkenhaug K.; Hirsch E.; Ji H. Blockade of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)δ or PI3Kγ reduces IL-17 and ameliorates imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like dermatitis. J. Immunol. 2012, 189, 4612–4620. 10.4049/jimmunol.1103173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka Y.; Yabuuchi T.; Oi T.; Kuroda S.; Fujii Y.; Ohtake H.; Inoue T.; Wakahara S.; Kimura K.; Fujita K.; Endo M.; Taguchi K.; Sekiguchi Y. Discovery of N-{5-[3-(3-hydroxypiperdin-1-yl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]-4-methyl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl}acetamide (TASP0415914) as an orally potent phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ inhibitor for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 7578–7583. 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce I.; Akhlaq M.; Bloomfield G. C.; Budd E.; Cox B.; Cuenoud B.; Finan P.; Gedeck P.; Hatto J.; Hayler J. F.; Head D.; Keller T.; Kirman L.; Leblanc C.; Grand D. L.; McCarthy C.; O’Connor D.; Owen C.; Oza M. S.; Pilgrim G.; Press N. E.; Sviridenko L.; Whitehead L. D. Development of isoform selective PI3K-kinase inhibitors as pharmacological tools for elucidating the PI3K pathway. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 5445–5450. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier P. N.; Martinez-Botella G.; Cornebise M.; Cottrell K. M.; Doran J. D.; Griffith J. P.; Mahajan S.; Maltais F.; Moody C. S.; Huck E. P.; Wang T.; Aronov A. M. Structural basis for isoform selectivity in a class of benzothiazole inhibitors of phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 517–521. 10.1021/jm500362j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier P. N.; Messersmith D.; Le Tiran A.; Bandarage U. K.; Boucher C.; Come J.; Cottrell K. M.; Damagnez V.; Doran J. D.; Griffith J. P.; Khare-Pandit S.; Krueger E. B.; Ledeboer M. W.; Ledford B.; Liao Y.; Mahajan S.; Moody C. S.; Roday S.; Wang T.; Xu J.; Aronov A. M. Discovery of highly isoform selective thiazolopiperidine inhibitors of phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 5684–5688. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd M. J.; Aronov A.; O’Dowd H.; Green J.. A selective inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-gamma. WO 2015/048318.

- Winkler D. G.; Faia K. L.; DiNitto J. P.; White K. F.; Brophy E. E.; Ping M. M.; Proctor J. L.; Lussier J.; Martin C. M.; Hoyt J. G.; Tillotson B.; Murphy E. L.; Lim A. R.; Thomas B. D.; MacDougall J. R.; Ren P.; Liu Y.; Li L.-S.; Jessen K. A.; Fritz C. C.; Dunbar J. L.; Porter J. R.; Rommel C.; Palombella V. J.; Changelian P. S.; Kutok J. L. PI3K-δ and PI3K-γ inhibition by IPI-145 abrogates immune responses and suppressed activity in autoimmune and inflammatory disease models. Chem. Biol. 2013, 20, 1364–1374. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight Z. A.; Gonzalez B.; Feldman M. E.; Zunder E. R.; Goldenberg D. D.; Williams O.; Loewith R.; Stokoe D.; Balla A.; Toth B.; Balla T.; Weiss W. A.; Williams R. L.; Shokat K. M. A pharmacological map of the PI3-K family defines a role for p110alpha in insulin signaling. Cell 2006, 125, 733–747. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt A.; Miller S.; Williams O.; Le D. D.; Houseman B. T.; Pacold J. I.; Gorrec F.; Hon W.-C.; Liu Y.; Rommel C.; Gaillard P.; Ruckle T.; Schwarz M. K.; Shokat K. M.; Shaw J. P.; Williams R. L. The p100 delta structure: mechanisms for selectivity and potency of new PI(3)K inhibitors. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010, 6, 117–124. 10.1038/nchembio.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reif K.; Okkenhaug K.; Sasaki T.; Penninger J. M.; Vanhaesebroeck B.; Cyster J. G. Cutting edge: Differential roles for phosphoinositide 3-kinases, p110γ and p110δ, in lymphocyte chemotaxis and homing. J. Immunol. 2004, 173, 2236–2240. 10.4049/jimmunol.173.4.2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutok J.; Ali J.; Brophy E.; Castro A.; DiNitto J.; Evans C.; Faia K.; Goldstein S.; Kosmider N.; Lescarbeau A.; Liu T.; Martin C.; McGovern K.; Nair S.; Pink M.; Proctor J.; Rausch M.; Sharma S.; Soglia J.; Tchaicha J.; Tremblay M.; Villegas V.; White K.; Winker D.; Palombella V.. The Potent and Selective Phosphoinositide-3-Kinase (PI3K)-γ Inhibitor, IPI-549, Inhibits Tumor Growth in Murine Syngeneic Solid Tumor Models through Alterations in the Immune Suppressive Microenvironment. In CRI-CIMT-EATI-AACR – The Inaugural International Cancer Immunotherapy Conference: Translating Science into Survival, New York, Sept. 16–19, 2015.

- NCT02637531: A dose-escalation study to evaluate the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of IPI-549. www.clinicaltrials.gov.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.