Abstract

In recent times, the diagnosis of breast lesions has mostly become dependent on core needle biopsies (CNBs) with a gradual reduction in the rate of performing fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC). Both the procedures have their pros and cons and outsmart each other taking into account different parameters. Both the methods are found to be fraught with loopholes, taking into account different performance indices, diagnostic accuracy and concordance, patient benefit, and cost-effectiveness. Unlike the popular belief of an absolute superiority of CNB over FNAC, the literature review does not reveal a very distinct demarcation in many aspects. We recommend judicious use of these diagnostic modalities in resource-limited settings and screening programs taking into account parameters such as palpability and availability of an experienced cytopathologist.

Keywords: Breast, core needle biopsy, fine-needle aspiration cytology

INTRODUCTION

Breast pathology is one of the most common pathologies encountered in routine practice. Not only the malignant lesions pose a major public health problem but also the benign lesions can contribute to the morbidity and their masquerade as malignancy can cause significant plight to the patients. The high incidence of breast malignancy, its relatively easy detection at an early stage, and effective treatment in the form of conservative surgery and chemotherapy had prompted a worldwide initiation of triple assessment including a clinical (palpation), radiologic (ultrasonography or mammography), and cytological (fine-needle aspiration cytology [FNAC]) assessment.[1,2] Although a part of the triple assessment, in recent times, a gradual trend of increase in the rate of core needle biopsy (CNB) is seen replacing the previously rampant occurrence of the FNAC. This gradual shift in the trend can be contributed by many factors although no study had yet conclusively proved a superiority of one procedure over the other. In this article, an effort is made to find out the reason of the shifting trend along with a comparative review analysis of these two procedures as depicted in the previous studies.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST BETWEEN FINE-NEEDLE ASPIRATION CYTOLOGY AND CORE NEEDLE BIOPSY

A breast FNAC or CNB is indicated in several clinical situations that have mainly diagnostic values except for some therapeutic implications of FNAC as in the case of a benign cyst which can be evacuated during FNAC. The diagnostic usage of these procedures includes a morphological diagnosis along with the application of necessary ancillary techniques such as performing immunochemistry for estrogen and progesterone receptors (ERs and PRs) in the malignant epithelial neoplasms. Both the procedures can be performed for palpable and nonpalpable lesions of the breast with or without the assistance of radiology. The artillery of FNAC is fraught with its (1) rapidity of diagnosis, (2) high acceptance, (3) cost-effectiveness, (4) high sensitivity and specificity, (5) ability to sample multiple areas at a single go, (6) preoperative planning, (7) sampling of metastatic as well as the primary site, (8) performance of ancillary techniques, and (9) a rapid psychological relief to the patient following a negative diagnosis [Table 1]. In addition, therapeutic aspiration is also possible in case of a cyst as mentioned earlier. FNAC can be employed in both palpable and nonpalpable lesions of the breast, and it is a relatively safe procedure with a low rate of procedure-related complications. However, hematoma formation, infection, or sometimes pneumothorax (especially after axillary lymph node FNAC) can be associated with FNAC.

Table 1.

Compare and contrast the diagnostic modalities: Core needle biopsy and fine-needle aspiration cytology

The major limitation of FNAC is its inability to diagnose some benign or borderline breast lesions and their distinction from the malignant lesions. As for example, preneoplastic lesions such as atypical ductal hyperplasia or in-situ changes cannot be confidently picked up by FNAC, and its distinction from an invasive malignancy is also very difficult. Similarly, benign lesions inducing extensive sclerosis, such as sclerosing adenosis, have long been considered to be the graveyard of cytopathologists. Another major limitation is the highly variable range of sensitivity and diagnostic accuracy of FNA smears depending on the experience of the cytopathologist. A variable and sometimes high rate of false negativity due to sampling error or error of interpretation have also prompted many clinicians to raise fingers against the efficiency of FNAC.

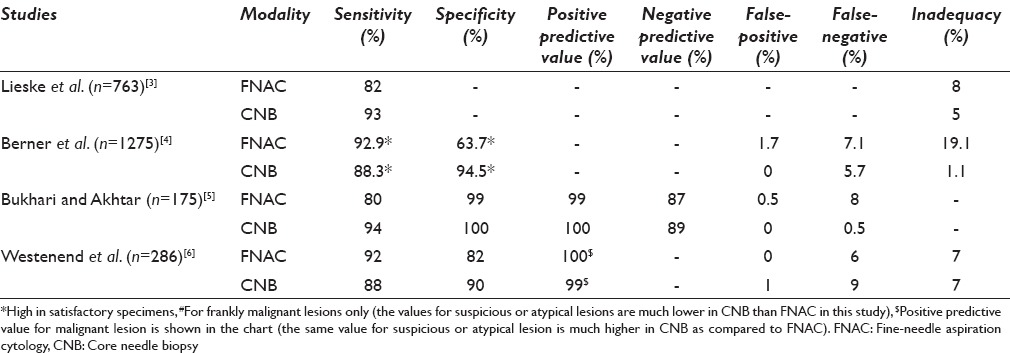

CNB has the obvious advantage of high sensitivity and specificity, high negative and positive predictive value, low inadequacy rate, and an edge in diagnosing the gray zone lesions of the breast as in lesions such as atypical ductal hyperplasia and in-situ carcinomas [Table 1]. However, the sensitivity, specificity, predictive values, and false-negativity rates are marginally different from FNAC in most of the studies [Table 2] although the range of variability is lower which possibly represents the difficulty in interpretation of cytology smears and the necessity of an experienced and trained cytopathologist.

Table 2.

Compare different parameters in fine-needle aspiration cytology and core needle biopsy in studies that have compared both these diagnostic modalities

Despite different studies quoting different performance rates, a true assessment of the relative superiority is often very difficult due to the involvement of multiple parameters and biases. As for example, CNB is often performed by the radiologist under radiology guidance with good yield of material and low inadequacy rate, whereas the adequacy and diagnostic sampling of FNAC material depend on the cytopathologist or radiologist working independently or in conjunction with each other performing the FNAC procedure rather than a radiologist alone and that also too varies according to the experience of the radiologist or cytopathologist. These biases are difficult to obviate in most of the studies. Moreover, there are very few studies comparing consecutive sampling of breast lesions, where one procedure follows the other and both the methods are applied to evaluate the same lesion. Hence, we will describe the procedures as per the parameters and will refer to the studies for comparative analysis.

Sensitivity

The sensitivity of FNAC varies from 77% to 97% in different studies[7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21] and is comparable with the sensitivity rate of the core biopsies[8,11,13] although the variability range in CNB is not as wide as in FNAC [Table 2]. Some studies also show a higher sensitivity of FNAC as compared to CNB[6,11] although CNB has been shown to have higher sensitivity in some other.[3,8,13] The variability of the sensitivity of FNAC whether it fares better than CNB or not depends on some parameters. Of these, the experience of cytopathologist, presence of cytopathologist at the time of the procedure, palpability, and size of the lesion are worthy to mention. Moreover, the nature of the lesion (suspicious, benign or frankly malignant) is another important determinant that dictates the sensitivity especially in case of FNAC. A study by Brancato et al.[11] has used the same operator and same lesion for performing both the procedures simultaneously thereby obviating some of the biases and has concluded that the sensitivity of both FNAC and CNB is comparable in lesions <2 cm or >5 cm, whereas CNB fares better in lesions ranging in size from 2 to 5 cm. The sensitivity of CNB is also higher in in-situ lesions and lesions detected as microcalcifications in mammography.[3] Hence, the sensitivity of FNAC appears to be equivalent or at times better than CNB, especially in frankly benign or malignant lesions that are clinically palpable, although it has the disadvantage of variability due to operator bias, and CNB has a distinctive edge in suspicious or in-situ lesions.

Specificity

Although most of the studies have reported a high specificity rate of FNAC (92–99%)[7,9,14,15,16,17,19] and one study has also reported 100% specificity rate;[18] the study by Hatada et al. has reported a low specificity[13] of FNA. Most of the studies have reported a higher specificity for CNB, especially so in lesions with suspicious diagnosis or the gray zone lesions of breast,[22,23,24,25,26] though the specificity of FNAC is well comparable in most.

Predictive values

The positive and negative predictive values of both FNAC and CNB are quite high, and most of the studies have recorded values of positive predictive value over 90%[20,27] and as high as 99% or 100%[14,16,18] in FNAC and comparable to CNB. The negative predictive value of FNAC is variable as compared to CNB and sometimes as low as 67%[15] though larger studies have shown comparable results as with CNB.[4,5,21,27] It must however be remembered that the positive predictive value of CNB is significantly higher in cases of B3/B4 (comparable to C3/C4 lesions of FNAC) lesions[28,29] (100% and 80% for CNB as compared to 78% and 18% for FNAC).[6]

False-positive and false-negative rates

The false-positive and false-negative rates of FNAC vary and as per Collaço et al., the rate has diminished in recent times and has stabilized.[16] Henceforth, the rates are different in different studies. However, most of the recent studies show a low false-positive rate of FNAC ranging from 0% to 2.5%[4,15,16,17,18,19,20] The false-negative rate of FNAC is, however, variable, high and is in the range of 5–10% although an even higher rate over and above 15% has also been documented.[4,16] The false-positive rate in CNB is low and in most of the studies comparable to FNAC. The false-negative rate in CNB is also variable and many of the studies register a rate even higher than that of FNAC[30,31] although the rate in CNB varies over a wider range, and no significant difference in false positivity or false negativity is registered in the larger studies that have compared both the procedures.[6,30,31] The reason for false negativity can be either sampling error or an interpretative error. It has been seen that an error of interpretation is more often a problem of FNAC as compared to CNB, which is intrinsic to the FNAC especially in gray-zone lesions. Moreover, obtaining an adequate sample in fibrocollagenous lesions (desmoplastic) is also a limitation inbuilt to the FNAC procedure leading to the false negativity and inadequacy.[32] Nevertheless, a provision of obtaining a sample from multiple areas of the lesions in FNAC in contrast to CNB gives a comparable result of false negativity.

Inadequacy of sampling

The inadequacy rates of FNAC and CNB do not reveal any significant difference[3,6,33] according to some of the studies, whereas the rate is much lower in CNB and also significantly different in a few other studies for both benign and malignant lesions.[11,13] It must be remembered that some of the lesions are difficult to be adequately sampled by FNAC although FNAC has the provision of multiple sampling from multiple sectors of a lesion. Lesions such as a radial scar or a complex sclerosing adenosis often suffer the brunt of inadequate sampling by FNAC along with low-grade malignancies, malignancies inciting intense desmoplasia, or even lobular carcinoma.[26,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41] A study by Lieske et al. shows that CNB is able to pick the diagnoses of the lesions that are B3 or above in 86% of the cases missed by FNAC, whereas FNAC can do so in only 65% of the cases missed by CNB.[3]

Rapidity, cost-effectiveness, turn-over time, and complications

FNAC is a much more rapid procedure than CNB, does not require any anesthesia, and can be done on an outpatient basis, and usually the whole procedure is completed within 10 min. Moreover, an assessment of sample adequacy or cellularity can be performed at the bedside by the cytopathologist by rapid staining, and a repeat FNA can be performed on the spot. In addition to the sampling of the breast lesion, a simultaneous assessment of the axillary lymph node is also possible at the same sitting. The overall expense of the whole procedure is very low, and a report can be generated within a few hours. The major complaint of the patient is pain after FNAC, and other complications such as pneumothorax are quite rare.[42] Unlike some popular beliefs, needle-seeding of the tumor cells is not documented. Sometimes, FNAC can be used for the therapeutic purposes such as the evacuation of a cyst or galactocele.

In contrast, CNB is a mini-operation that requires proper anesthesia and needs radiology guidance; the procedure takes a longer time with a higher turn-around time. There is no provision for checking the sample adequacy on the spot, and the expense is higher as that of FNAC. Pain remains the common complaint after the procedure, but albeit at a low rate, the incidence of complications is higher than that of FNAC.

Many authors think that considering cost-effectiveness, rapidity, turn-around time, and complication rate, FNAC is a much better procedure and has the potential to do good, especially in resource-limited settings[2,5,21] although some studies put forward the arguments of repeat procedure or radiology-guidance in nonpalpable lesions, limiting its cost-effectiveness.[18,32,43,44,45,46,47]

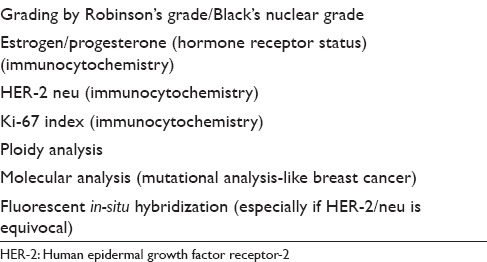

Ancillary tests

Breast malignancies in the modern era need to be evaluated preoperatively, and evaluation of the hormonal status (ER and PR) has become almost part and parcel of the preoperative evaluation as it navigates further patient management. Further, an assessment of human epidermal growth factor receptor-2/neu receptor status and proliferative index of the breast lesion is also important. These parameters taken together help the clinician to choose appropriate chemotherapy regimen, prognosticate breast malignancy and also correlate with the molecular classification of breast malignancies. Although some studies have employed these tests on cytology material with satisfactory results,[48,49] a general consensus is to perform the immunohistochemical stains on formalin-fixed-paraffin-embedded core biopsy material providing higher reliability.[50,51,52]

Efficacy of fine-needle aspiration cytology and core needle biopsy to diagnose different breast lesions

In general, FNAC has the limitation of clinching the diagnosis of some of the breast lesions that form the “true gray zone lesions” of the breast. These lesions include fibroepithelial lesions of the breast, fibrocystic disease, papillary lesions of the breast, radial scar and sclerosing adenosis, flat epithelial atypia, borderline proliferative lesions such as atypical ductal hyperplasia, in-situ carcinoma, low-grade carcinoma, lobular carcinoma, and many others.[28,34,53,54,55,56,57,58,59] It must be noted that these lesions are the major cause of variability of sensitivity, specificity, false negativity, or false positivity of FNAC and also contribute to the variability of the results in different studies. Another noteworthy feature of these lesions is that they, unlike commonly believed, are not easily diagnosed even by CNBs and a provisional report needs to be issued. Reporting by an experienced cytopathologist reduces the false-negative rate and improves the specificity, but it cannot be overcome completely. The discussion on individual gray zone entity is beyond the scope of our review though we will discuss the difficulties in brief and compare both the procedures with their respective diagnostic superiority or comparability.

Of these, a clear-cut distinction between fibroadenoma and benign phyllodes tumor is often not possible either by FNAC or CNB, and a careful examination of resection specimen is often required. Many pathologists prefer to issue a report of a benign fibroepithelial lesion in doubtful cases, suggesting a complete resection for definitive diagnosis.[23,54,60]

Papillary lesions of the breast comprise a spectrum of benign, borderline, and malignant lesions. Although CNB offers an advantage of diagnosing the papillary lesions, definiteness lacks. FNAC in contrast often stumbles in suggesting a possibility of a papillary lesion and a distinction of nonpapillary lesions such as fibroadenoma from the true papillary lesion is also often elusive.[58,61,62,63]

Radial scar and complex sclerosing lesions are considered to be nightmares for both cyto and histopathologist and pose a significant diagnostic problem.[37,38]

Flat epithelial atypia and other forms of columnar cell changes are very difficult to diagnose with FNAC, and CNB is definitely beneficial in this aspect.

The major loophole of FNAC, however, lies in its inability to distinguish between in-situ carcinomas, low-grade malignancies, and invasive malignancies. Though fat infiltration, elastoid stromal fragments, stromal infiltration, tubule, or intracellular lumina formation is proposed by the cytopathologists as evidence of malignancy, fallacies lie in their absoluteness. Atypical ductal hyperplasia and ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) have quantitative difference rather than a qualitative distinction and are presently impossible to diagnose by FNAC.[22,24,64,65,66,67,68] Moreover, lobular carcinoma is an entity that is commonly missed in FNAC due to higher inadequacy rate, lower cellularity, and deceptively bland appearance of the tumor cells.[26,39,40] CNB offers an advantage over FNAC in this aspect.

Other histopathological prognostic indices

The prognostication of breast malignancies depends on many factors including tumor size, tumor grade, tumor type, presence or absence of in-situ component, lymphovascular emboli, perineural invasion, and proliferation index. The hormonal status is another important prognostic marker among many other.

The cytological nuclear grading has good correlation with the histopathological grade and cytology can also use morphometry as an important adjunct.[69,70] However, a comment on an in-situ component, presence or absence of lymphovascular embolus, or perineural invasion cannot be made on FNAC smears.

HOW GOOD IS A COMBINATORIAL APPROACH?

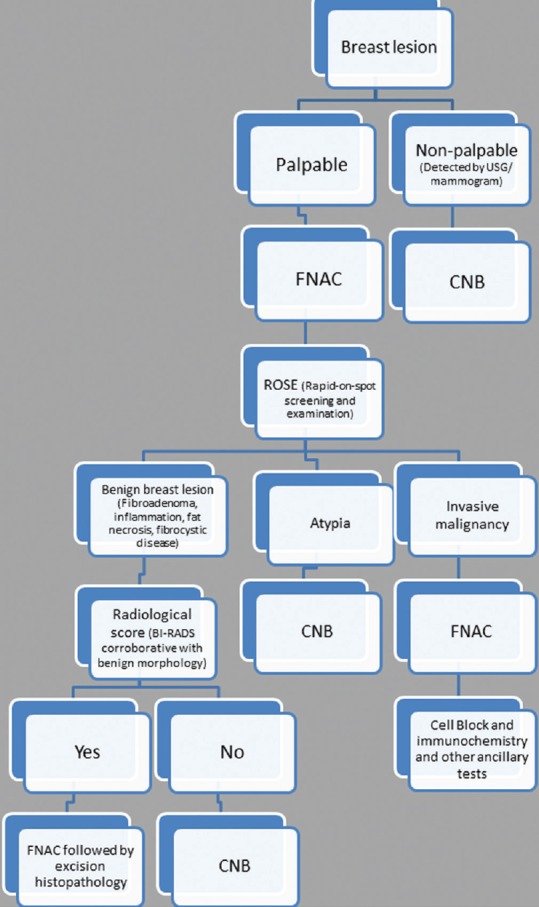

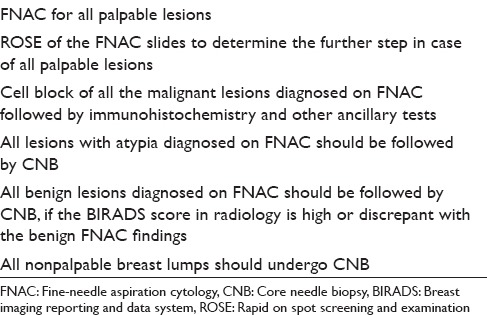

In brief, FNAC has its advantages in the form of rapidity, low cost, and minimal invasion with good sensitivity and specificity. On the other hand, core biopsy provides more specificity than FNAC with additional advantage of ancillary tests and comment on the histopathological prognostic markers. This is especially true for the gray zone lesions of the breast. Some of the authors have already tried to take a combinatorial approach including both FNAC and CNB along with intraoperative touch imprint or scrape cytology to assess its combined utility.[3,5,6,11,13] All these studies have shown a heightened sensitivity and specificity to the extent of 100% when a combined approach has been taken. Moreover, Bukhari and Akhtar have shown that a combination of mammography, FNAC, and CNB is more accurate, reliable and has good acceptability as well. These results have prompted many centers to take a combinatorial approach adding diagnostic specificity with rapidity. Needless to say, this requires an experienced cytopathologist to do an on-spot screening of aspirated material to decide the necessity of a further CNB. Based on these data, we have proposed a diagnostic algorithm for breast masses [Figure 1]. We have also proposed the types of lesions and the diagnostic modalities that would probably be the most suitable and cost-effective in Table 3. The diagnostic and prognostic information that can be provided to the clinician from the FNAC material has also been tabulated in Table 4. This approach appears cost-effective and accurate as the limitations of each of the procedure can be partially offset by each.

Figure 1.

Algorithmic approach of breast lesion by fine-needle aspiration cytology and core needle biopsy

Table 3.

Different diagnostic modalities, best suitable for the type of lesion

Table 4.

Diagnostic and prognostic information that could be provided on the fine-needle aspiration cytology material

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

We have reviewed the literature to compare different performance parameters of the two major diagnostic procedures of breast lesions, namely FNAC and CNB. There has been a recent paradigm shift toward performing CNB rather than FNAC. Many factors are implicated in such shift including the availability of an experienced cytopathologist.

Although the general bias is toward a superiority of CNB, we have found that FNAC has its advantages and similarly, CNB has its limitations. The rapidity of procedure and reporting of FNAC with low cost provides sufficient benefit to the patients, especially in developing countries and resource-limited setting. In addition, FNAC provides good sensitivity, specificity, predictive value, and adequacy that is often comparable to CNB and at times superior to it. However, a significant range of such performance parameters speaks volumes about the subtlety, delicacy, necessity of experience, and difficulty in interpreting FNAC smears. Moreover, FNAC fails to detect some of the important diagnostic and prognostic parameters such as in-situ carcinomas and fibrocollagenous lesions where CNB is definitely superior. Moreover, pathologists are more in verse in interpreting the immunochemistry in biopsy slides.

The superiority of FNA also lies in the B2/C2 lesions such as fibroadenoma, constituting a major chunk of cases in an FNA clinic. Diagnosing a benign entity puts an end to an anticipated surgery in a patient. Aspiration of a cyst, simultaneous aspiration of an axillary lymph node along with the primary tumor in the breast, aspiration in a patient on anticoagulation therapy (CNB has more chance of trauma and the subsequent complications) are the benefits of FNA even in nonresource-limited settings. The presence of multifocal tumor or satellite lesions where multiple aspirates are to be taken, a deeper location of tumor close to the chest wall or in the vicinity of a breast implant also necessitates the role of FNA. Despite these facts, it must be remembered that FNA has a limited role in gray zone lesions of the breast (B3/C3 and B4/C4). Moreover, a specific histopathological diagnosis is required in most of the lesions falling over and above B3/C3 such as atypical ductal hyperplasia, in-situ carcinoma, or papillary lesions for further management of patients (surgery with and without chemotherapy), and FNA is fraught with its limitations in this regard. Moreover, reporting of many of the prognostic parameters (mitosis, lymphovascular emboli, perineural invasion, percentage presence of the DCIS component) and ancillary tests is virtually impossible in aspirate smears.

In resource-limited settings and with the help of triple assessment, a judicious use of FNAC is preferable over CNB especially so in palpable lesions of the breast and screening programs. The clinicians should also know the advantages and disadvantages of both the procedures over each other and decide accordingly. We strongly oppose the general tendency of performing CNB in all cases without a clinico-radiological discrimination.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

There is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The first author (SM) has drafted the whole article. The second author (PD) has given the necessary guidance and advice regarding the execution of the article.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This is a review article and there is no question on ethical justification of the study.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

CNB - Core Needle Biopsy

ERs and PRs - Estrogen and Progesterone Receptors

FNAC - Fine-Needle Aspiration Cytology.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

Contributor Information

Suvradeep Mitra, Email: sugreebm@gmail.com.

Pranab Dey, Email: deypranab@hotmail.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tabbara SO, Frost AR, Stoler MH, Sneige N, Sidawy MK. Changing trends in breast fine-needle aspiration: Results of the Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology Survey. Diagn Cytopathol. 2000;22:126–30. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(200002)22:2<126::aid-dc15>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed I, Nazir R, Chaudhary MY, Kundi S. Triple assessment of breast lump. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2007;17:535–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lieske B, Ravichandran D, Wright D. Role of fine-needle aspiration cytology and core biopsy in the preoperative diagnosis of screen-detected breast carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:62–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berner A, Davidson B, Sigstad E, Risberg B. Fine-needle aspiration cytology vs. core biopsy in the diagnosis of breast lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;29:344–8. doi: 10.1002/dc.10372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bukhari MH, Akhtar ZM. Comparison of accuracy of diagnostic modalities for evaluation of breast cancer with review of literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37:416–24. doi: 10.1002/dc.21000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Westenend PJ, Sever AR, Beekman-De Volder HJ, Liem SJ. A comparison of aspiration cytology and core needle biopsy in the evaluation of breast lesions. Cancer. 2001;93:146–50. doi: 10.1002/cncr.9021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Day C, Moatamed N, Fimbres AM, Salami N, Lim S, Apple SK. A retrospective study of the diagnostic accuracy of fine-needle aspiration for breast lesions and implications for future use. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:855–60. doi: 10.1002/dc.20933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poole GH, Willsher PC, Pinder SE, Robertson JF, Elston CW, Blamey RW. Diagnosis of breast cancer with core-biopsy and fine needle aspiration cytology. Aust N Z J Surg. 1996;66:592–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1996.tb00825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feichter GE, Haberthür F, Gobat S, Dalquen P. Breast cytology. Statistical analysis and cytohistologic correlations. Acta Cytol. 1997;41:327–32. doi: 10.1159/000332520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barra Ade A, Gobbi H, de L Rezende CA, Gouvêa AP, de Lucena CE, Reis JH, et al. A comparision of aspiration cytology and core needle biopsy according to tumor size of suspicious breast lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:26–31. doi: 10.1002/dc.20748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brancato B, Crocetti E, Bianchi S, Catarzi S, Risso GG, Bulgaresi P, et al. Accuracy of needle biopsy of breast lesions visible on ultrasound: Audit of fine needle versus core needle biopsy in 3233 consecutive samplings with ascertained outcomes. Breast. 2012;21:449–54. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frayne J, Sterrett GF, Harvey J, Goodwin P, Townsend J, Ingram D, et al. Stereotactic 14 gauge core-biopsy of the breast: Results from 101 patients. Aust N Z J Surg. 1996;66:585–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1996.tb00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hatada T, Ishii H, Ichii S, Okada K, Fujiwara Y, Yamamura T. Diagnostic value of ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy, core-needle biopsy, and evaluation of combined use in the diagnosis of breast lesions. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190:299–303. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(99)00300-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sneige N. Fine-needle aspiration of the breast: A review of 1,995 cases with emphasis on diagnostic pitfalls. Diagn Cytopathol. 1993;9:106–12. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840090122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mizuno S, Isaji S, Ogawa T, Tabata M, Yamagiwa K, Yokoi H, et al. Approach to fine-needle aspiration cytology-negative cases of breast cancer. Asian J Surg. 2005;28:13–7. doi: 10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60251-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collaço LM, de Lima RS, Werner B, Torres LF. Value of fine needle aspiration in the diagnosis of breast lesions. Acta Cytol. 1999;43:587–92. doi: 10.1159/000331150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi YD, Choi YH, Lee JH, Nam JH, Juhng SW, Choi C. Analysis of fine needle aspiration cytology of the breast: A review of 1,297 cases and correlation with histologic diagnoses. Acta Cytol. 2004;48:801–6. doi: 10.1159/000326449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubin M, Horiuchi K, Joy N, Haun W, Read R, Ratzer E, et al. Use of fine needle aspiration for solid breast lesions is accurate and cost-effective. Am J Surg. 1997;174:694–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(97)00192-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishikawa T, Hamaguchi Y, Tanabe M, Momiyama N, Chishima T, Nakatani Y, et al. False-positive and false-negative cases of fine-needle aspiration cytology for palpable breast lesions. Breast Cancer. 2007;14:388–92. doi: 10.2325/jbcs.14.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Domínguez F, Riera JR, Tojo S, Junco P. Fine needle aspiration of breast masses. An analysis of 1,398 patients in a community hospital. Acta Cytol. 1997;41:341–7. doi: 10.1159/000332522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmed HG, Ali AS, Almobarak AO. Utility of fine-needle aspiration as a diagnostic technique in breast lumps. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37:881–4. doi: 10.1002/dc.21115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sneige N, Staerkel GA. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of ductal hyperplasia with and without atypia and ductal carcinoma in situ. Hum Pathol. 1994;25:485–92. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(94)90120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krishnamurthy S, Ashfaq R, Shin HJ, Sneige N. Distinction of phyllodes tumor from fibroadenoma: A reappraisal of an old problem. Cancer. 2000;90:342–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shin HJ, Sneige N. Is a diagnosis of infiltrating versus in situ ductal carcinoma of the breast possible in fine-needle aspiration specimens? Cancer. 1998;84:186–91. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980625)84:3<186::aid-cncr11>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sidawy MK, Stoler MH, Frable WJ, Frost AR, Masood S, Miller TR, et al. Interobserver variability in the classification of proliferative breast lesions by fine-needle aspiration: Results of the Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology Study. Diagn Cytopathol. 1998;18:150–65. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(199802)18:2<150::aid-dc12>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdulla M, Hombal S, al-Juwaiser A, Stankovich D, Ahmed M, Ajrawi T. Cellularity of lobular carcinoma and its relationship to false negative fine needle aspiration results. Acta Cytol. 2000;44:625–32. doi: 10.1159/000328538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boerner S, Fornage BD, Singletary E, Sneige N. Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of nonpalpable breast lesions: A review of 1885 FNA cases using the National Cancer Institute-supported recommendations on the uniform approach to breast FNA. Cancer. 1999;87:19–24. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990225)87:1<19::aid-cncr4>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanhoush R, Jorda M, Gomez-Fernandez C, Wang H, Mirzabeigi M, Ghorab Z, et al. ‘Atypical’ and ‘suspicious’ diagnoses in breast aspiration cytology. Cancer. 2004;102:164–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The uniform approach to breast fine-needle aspiration biopsy. National Cancer Institute Fine-Needle Aspiration of Breast Workshop Subcommittees. Diagn Cytopathol. 1997;16:295–311. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(1997)16:4<295::aid-dc1>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ballo MS, Sneige N. Can core needle biopsy replace fine-needle aspiration cytology in the diagnosis of palpable breast carcinoma. A comparative study of 124 women. Cancer. 1996;78:773–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960815)78:4<773::AID-CNCR13>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun W, Li A, Abreo F, Turbat-Herrera E, Grafton WD. Comparison of fine-needle aspiration cytology and core biopsy for diagnosis of breast cancer. Diagn Cytopathol. 2001;24:421–5. doi: 10.1002/dc.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pisano ED, Fajardo LL, Tsimikas J, Sneige N, Frable WJ, Gatsonis CA, et al. Rate of insufficient samples for fine-needle aspiration for nonpalpable breast lesions in a multicenter clinical trial: The Radiologic Diagnostic Oncology Group 5 Study. The RDOG5 investigators. Cancer. 1998;82:679–88. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980215)82:4<679::aid-cncr10>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Britton PD, Flower CD, Freeman AH, Sinnatamby R, Warren R, Goddard MJ, et al. Changing to core biopsy in an NHS breast screening unit. Clin Radiol. 1997;52:764–7. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(97)80156-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deb RA, Matthews P, Elston CW, Ellis IO, Pinder SE. An audit of “equivocal” (C3) and “suspicious” (C4) categories in fine needle aspiration cytology of the breast. Cytopathology. 2001;12:219–26. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2303.2001.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shabb NS, Boulos FI, Abdul-Karim FW. Indeterminate and erroneous fine-needle aspirates of breast with focus on the ‘true gray zone’: A review. Acta Cytol. 2013;57:316–31. doi: 10.1159/000351159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.al-Kaisi N. The spectrum of the “gray zone” in breast cytology. A review of 186 cases of atypical and suspicious cytology. Acta Cytol. 1994;38:898–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamb J, McGoogan E. Fine needle aspiration cytology of breast in invasive carcinoma of tubular type and in radial scar/complex sclerosing lesions. Cytopathology. 1994;5:17–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.1994.tb00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenberg ML, Camaris C, Psarianos T, Ung OA, Lee WB. Is there a role for fine-needle aspiration in radial scar/complex sclerosing lesions of the breast? Diagn Cytopathol. 1997;16:537–42. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(199706)16:6<537::aid-dc13>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hwang S, Ioffe O, Lee I, Waisman J, Cangiarella J, Simsir A. Cytologic diagnosis of invasive lobular carcinoma: Factors associated with negative and equivocal diagnoses. Diagn Cytopathol. 2004;31:87–93. doi: 10.1002/dc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lerma E, Fumanal V, Carreras A, Esteva E, Prat J. Undetected invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast: Review of false-negative smears. Diagn Cytopathol. 2000;23:303–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0339(200011)23:5<303::aid-dc3>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Layfield LJ, Dodd LG. Cytologically low grade malignancies: An important interpretative pitfall responsible for false negative diagnoses in fine-needle aspiration of the breast. Diagn Cytopathol. 1996;15:250–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0339(199609)15:3<250::AID-DC15>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salhab M, Al Sarakbi W, Perry N, Mokbel K. Pneumothorax after a clinical breast fine-needle aspiration of a lump in a patient with Poland's syndrome. Int Semin Surg Oncol. 2005;2:14. doi: 10.1186/1477-7800-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Layfield LJ, Bentz JS, Gopez EV. Immediate on-site interpretation of fine-needle aspiration smears: A cost and compensation analysis. Cancer. 2001;93:319–22. doi: 10.1002/cncr.9046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silverman JF, Lannin DR, O’Brien K, Norris HT. The triage role of fine needle aspiration biopsy of palpable breast masses. Diagnostic accuracy and cost-effectiveness. Acta Cytol. 1987;31:731–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nasuti JF, Gupta PK, Baloch ZW. Diagnostic value and cost-effectiveness of on-site evaluation of fine-needle aspiration specimens: Review of 5,688 cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;27:1–4. doi: 10.1002/dc.10065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lannin DR, Silverman JF, Walker C, Pories WJ. Cost-effectiveness of fine needle biopsy of the breast. Ann Surg. 1986;203:474–80. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198605000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Willems SM, van Deurzen CH, van Diest PJ. Diagnosis of breast lesions: Fine-needle aspiration cytology or core needle biopsy? A review. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:287–92. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2011-200410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kumar SK, Gupta N, Rajwanshi A, Joshi K, Singh G. Immunochemistry for oestrogen receptor, progesterone receptor and HER2 on cell blocks in primary breast carcinoma. Cytopathology. 2012;23:181–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2011.00853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Durgapal P, Mathur SR, Kalamuddin M, Datta Gupta S, Parshad R, Julka PK, et al. Assessment of Her-2/neu status using immunocytochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization on fine-needle aspiration cytology smears: Experience from a tertiary care centre in India. Diagn Cytopathol. 2014;42:726–31. doi: 10.1002/dc.23088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rakha EA, Ellis IO. An overview of assessment of prognostic and predictive factors in breast cancer needle core biopsy specimens. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:1300–6. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.045377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Konofaos P, Kontzoglou K, Georgoulakis J, Megalopoulou T, Zoumpouli C, Christoni Z, et al. The role of ThinPrep cytology in the evaluation of estrogen and progesterone receptor content of breast tumors. Surg Oncol. 2006;15:257–66. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Diest PJ, van der Wall E, Baak JP. Prognostic value of proliferation in invasive breast cancer: A review. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:675–81. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2003.010777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rosa M, Mohammadi A, Masood S. The value of fine needle aspiration biopsy in the diagnosis and prognostic assessment of palpable breast lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;40:26–34. doi: 10.1002/dc.21497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shabb NS. Phyllodes tumor. Fine needle aspiration cytology of eight cases. Acta Cytol. 1997;41:321–6. doi: 10.1159/000332519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Howell LP. Equivocal diagnoses in breast aspiration biopsy cytology: Sources of uncertainty and the role of “atypical/indeterminate” terminology. Diagn Cytopathol. 1999;21:217–22. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(199909)21:3<217::aid-dc15>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jamal AA, Mansoor I. Analysis of false positive and false negative cytological diagnosis of breast lesions. Saudi Med J. 2001;22:67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Simsir A, Cangiarella J. Challenging breast lesions: Pitfalls and limitations of fine-needle aspiration and the role of core biopsy in specific lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;40:262–72. doi: 10.1002/dc.21630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Simsir A, Waisman J, Thorner K, Cangiarella J. Mammary lesions diagnosed as “papillary” by aspiration biopsy: 70 cases with follow-up. Cancer. 2003;99:156–65. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kline TS. Masquerades of malignancy: A review of 4,241 aspirates from the breast. Acta Cytol. 1981;25:263–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kollur SM, El Hag IA. FNA of breast fibroadenoma: Observer variability and review of cytomorphology with cytohistological correlation. Cytopathology. 2006;17:239–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2006.00360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Michael CW, Buschmann B. Can true papillary neoplasms of breast and their mimickers be accurately classified by cytology? Cancer. 2002;96:92–100. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bardales RH, Suhrland MJ, Stanley MW. Papillary neoplasms of the breast: Fine-needle aspiration findings in cystic and solid cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 1994;10:336–41. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840100409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dawson AE, Mulford DK. Benign versus malignant papillary neoplasms of the breast. Diagnostic clues in fine needle aspiration cytology. Acta Cytol. 1994;38:23–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McKee GT, Tambouret RH, Finkelstein D. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of the breast: Invasive vs. in situ carcinoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 2001;25:73–7. doi: 10.1002/dc.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McKee GT, Tildsley G, Hammond S. Cytologic diagnosis and grading of ductal carcinoma in situ. Cancer. 1999;87:203–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cangiarella J, Waisman J, Simsir A. Cytologic findings with histologic correlation in 43 cases of mammary intraductal adenocarcinoma diagnosed by aspiration biopsy. Acta Cytol. 2003;47:965–72. doi: 10.1159/000326669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dillon MF, McDermott EW, Quinn CM, O’Doherty A, O’Higgins N, Hill AD. Predictors of invasive disease in breast cancer when core biopsy demonstrates DCIS only. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93:559–63. doi: 10.1002/jso.20445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Maygarden SJ, Brock MS, Novotny DB. Are epithelial cells in fat or connective tissue a reliable indicator of tumor invasion in fine-needle aspiration of the breast? Diagn Cytopathol. 1997;16:137–42. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(199702)16:2<137::aid-dc8>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Robinson IA, McKee G, Nicholson A, D’Arcy J, Jackson PA, Cook MG, et al. Prognostic value of cytological grading of fine-needle aspirates from breast carcinomas. Lancet. 1994;343:947–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.van Diest PJ, Mouriquand J, Schipper NW, Baak JP. Prognostic value of nucleolar morphometric variables in cytological breast cancer specimens. J Clin Pathol. 1990;43:157–9. doi: 10.1136/jcp.43.2.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]