Abstract

Purpose of the Study:

Despite important connections between relationships, health, and well-being, little is known about later-life couples’ daily lives and experiences, especially those who are frail. Our aim was to advance knowledge by gaining an in-depth understanding of married and unmarried couples’ intimate and social relationships in assisted living (AL) and by generating an explanatory theory.

Design and Methods:

Using Grounded Theory Methods, we build on past research and analyze qualitative data from a 3-year mixed-methods study set in eight diverse AL settings located in the state of Georgia. Data collection included participant observation and informal and formal interviews yielding information on 29 couples, 26 married and 3 unmarried.

Results:

Defined by their relationships with one another and those around them, couples’ experiences were variable and involved a process of reconciling individual and shared situations. Analysis affirms and expands an existing typology of couples in AL. Our conceptual model illustrates the multilevel factors influencing the reconciliation process and leading to variation. Findings highlight the strengths and burdens of late-life couplehood and have implications for understanding these intimate ties beyond AL.

Implications:

Intimate and social relationships remain significant in later life. Strategies aimed at supporting couples should focus on individual and shared situations, particularly as couples’ experience physical and cognitive decline across time.

Keywords: Couples, Long-term care, Intimate relationships, Social relationships, Assisted living facilities, Qualitative analysis: Grounded Theory

Intimate relationships profoundly influence older adults’ health and well-being (Birditt, Newton, & Hope, 2014), social networks (Akiyama, Elliot, & Antonucci, 2000), and daily lives. Despite this well-established influence, research has not fully addressed the heterogeneity and complexity of married and unmarried couples’ lives, particularly in the contexts of advanced age, health decline, and long-term care (LTC) settings such as assisted living (AL). Although couples are a minority in AL, being coupled simultaneously influences social experiences and environments and may become more common as the population ages (Kemp, 2008, 2012; Kemp, Ball, Hollingsworth, & Perkins, 2012).

Married couples in AL have received scant research attention and unmarried couples, even less. Understanding their experiences will address knowledge gaps regarding the “strengths” and “burdens” of late-life relationships, the influences of relocating, and “broader life conditions that affect couples” (see Walker & Luszcz, 2009, p. 475). In this article, we build on past work, merge research on late-life couples with research on social relationships in AL, and present analysis of longitudinal qualitative data examining couples, collected over a 1-year period in multiple AL settings. We seek to advance knowledge of later-life intimate and social relationships, including how and why they vary and with what outcomes.

Most research on older couples investigates marriage and focuses on marital satisfaction or quality, often comparing old and young (Bookwala & Jacobs, 2004). Research casts an overall positive image of late-life marriages (Korporaal, van Groenou, & van Tilburg, 2013). Hoppmann and Gerstorf (2009, p. 451) attribute this “rosy” image to studying “positively selected groups of older couples” in long-lasting marriages and with no major health problems.

Viewed through a life course lens, conceptualizing couples’ lives as linked and embedded in broader relationships and contexts is essential (Warner & Kelley-Moore, 2012). An emerging line of inquiry investigates health and illness within later-life marriages (Korporaal et al., 2013). Primarily quantitative, much of this work examines relationships between marital quality and health and well-being (e.g., Birditt et al., 2014; Peek, Stimpson, Townsend, & Markides, 2006) or health symptom spillover between spouses (e.g., Bookwala, 2014; Yorgason, Roper, Sandberg, & Berg, 2012). Another research trajectory focuses on spousal caregiving. Korporaal et al. (2013, p. 1280) note this literature often separates “the patient from the caregiver,” overlooking multidirectional support exchanges and the fact both partners may have health challenges.

Later-life spouses often rely on one another to cope with physical decline or illness (Walker & Luszcz, 2009). However, “collaborative coping,” which involves “pooling resources and joint problem-solving and coping” is not universal (Berg et al., 2008, p. 509). Collaboration may depend on the quality of the relationship, the nature of the illness, and “illness ownership” (i.e., the degree to which the illness is perceived as belonging to the individual or couple) and influences management of and response to illness (Berg & Upchurch, 2007), including the need to relocate to AL.

Decline and disablement of any type can challenge functioning (Korporaal, van Groenou, & van Tilburg, 2008) and require couples to renegotiate daily life and roles. Cognitive impairment may prove especially stressful (Sanders & Power, 2009) and is associated with accelerated health decline and mortality among spousal caregivers (Dassel & Carr, 2014). Almost half of AL residents have dementia (Caffrey et al., 2012), which, together with other chronic conditions, impacts relationships (Sandhu, Kemp, Ball, Burgess, & Perkins, 2013).

Research on couples in LTC generally, and AL, is limited. Spouses in Gladstone’s (1995a, 1995b) pioneering couples research reported their relocation to LTC had little influence, although some grew more dependent; others became lonely as spouses established independence. More recently, Moss and Moss (2007) examined men’s experiences in nursing homes and AL and found being married prevented and created loneliness. Having a spouse provided companionship, but sometimes limited social engagement.

The present analysis builds on research from two of our recent AL studies. The first, “Married Couples in AL,” was exploratory and examined 20 couples’ pathways to and lives in AL, qualitatively and in-depth (Kemp, 2008, 2012). Couples’ pathways are “synchronous” or “asynchronous” in terms of spouses’ health status and need to relocate. Analysis identified four main interaction patterns denoting how spouses related to one another (interdependence levels) and others (social integration) (see Table 4). Synchronicity, spousal caregiving, and feelings of obligation shaped patterns. This study was cross-sectional, focused on married couples, and did not include staff or other residents’ perspectives.

Table 4.

Couples Interaction Pattern Typology

| Type | Definition/characteristics | Number of couples (N = 29) (married, N = 26; unmarried, N = 3) |

|---|---|---|

| Independent | Spouses who “enjoyed one another’s company, but actively negotiated time apart.” (Kemp, 2008, p. 243) | 3 (2 married; 1 unmarried) |

| Inter-reliant | These “spouses were inseparable and rarely left one another’s side.” (Kemp, 2008, p. 243). | |

| Socially engaged | Inter-reliant couples who were involved in facility life and activities together. | 3 (1 married; 2 unmarried) |

| Self-isolated | Inter-reliant couples who rarely participated in facility life or engaged with others in the setting often remaining in their apartments. | 7 (all married) |

| Socially marginalized a | Inter-reliant who couples spent time in common areas, but other residents tended to avoid them. | 1 (married) |

| Restricted independent | Within these couples - “one spouse typically left the other spouse behind . . . to engage in time-restricted activities . . .” (Kemp, 2008, pp. 244–45) either because of perceived caregiving responsibilities or the restrictive nature of one spouse. | |

| Caregiving spouse | Restricted-independent couples where one spouse was caring for the other and limited their engagement with others. | 12 (married) |

| Restrictive spouse a | Restricted-independent couples in which one spouse monitors and limits the activities of the other spouse. | 1 (married) |

| Coexistenta | Spouses had minimal interaction with one another or others. They coexist within their marriage and the facility and are either socially marginalized or self-isolated. | |

| Socially marginalized a | Couples tended to be avoided and ignored by their fellow residents. | 1 (married) |

| Self-isolated a | Couples tended to remain mostly in their apartments, avoiding others. | 1 (married) |

aNew couple type or sub-types found in the present analysis.

The second study, “Social Relationships in Assisted Living,” examined residents’ social lives and provides data for this article. The study compliments other AL researchers’ conclusions that coresident relationships influence well-being (e.g., Burge & Street, 2010; Park, 2009; Street & Burge, 2012; Street, Burge, Quadagno, & Barrett, 2007). Our quantitative assessment of residents’ social networks found that having a higher proportion of family members was the strongest predictor of well-being, but having some coresident ties also had a significant positive effect (Perkins, Ball, Kemp, & Hollingsworth, 2013). Further underscoring the potential value of coresident relationships, other AL researchers find that residents often prefer more contact with family and friends than they receive (Tompkins, Ihara, Cusick, & Park, 2012).

Coresident relationships in AL range from strangers and friends to enemies and romantic partners (Kemp et al., 2012). Reflecting the dynamism of relationships, residents engage in the process of “negotiating social careers in AL.” Careers begin with the move and are negotiated over time, vary in content and nature, and are influenced by multilevel factors, including individual factors, such as functional status (see also Sandhu et al., 2013). Residents with spouses, siblings, or romantic partners have “built-in companionship.” Interdependence, particularly regarding caregiving, limits coresident relationships among some couples, but sometimes is preferred over independence. Further analysis reveals that end-of-life care and death, are part of the AL social environment and can profoundly affect the experiences of coupled and uncoupled residents (Ball, Kemp, Hollingsworth, & Perkins, 2014; Perkins et al., 2013).

Our recent synthesis of theoretical and empirical work resulted in the “Convoys of Care” model (Kemp, Ball, & Perkins, 2013). It builds on Kahn and Antonucci’s (1980) Convoy Model of Social Relations, expanding it to include contributions from formal (i.e., paid) caregivers. Care convoys consist of care recipients and their evolving network of informal and formal caregivers. They are shaped by multilevel factors, including regulatory and care-setting influences and those related to care recipients and providers. Being coupled influences care networks in AL and beyond.

The research outlined above is a sensitizing framework for our analysis. Unlike past late-life couples’ research, our current analysis uses qualitative data collected over time through multiple methods and includes the perspectives of married and unmarried couples, as well as uncoupled residents and others in the setting. Our aim is to obtain an in-depth understanding of couples’ intimate and social lives in AL and to generate theory grounded in the data. We ask: (a) How do couples experience social careers in AL? and (b) What factors influence their experiences?

Design and Methods

We use Grounded Theory Method (GTM) as outlined by Corbin and Strauss (2008) and draw on qualitative data from a 3-year (2008–2011) mixed-methods study which aimed to learn how to create AL environments that support residents’ ability to negotiate and manage their coresident relationships. Georgia State University’s Institutional Review Board approved the study. For anonymity, we use pseudonyms.

Setting and Sample

The AL sample included eight communities in Georgia, a state which reflects the variation in AL found nationwide (Ball & Perkins, 2010). We purposively selected these sites to achieve variation in size, location, ownership, fees, and resident characteristics (Table 1). Seven sites had couples during the study, yielding a total of 29 (26 married and 3 unmarried). Each location had a history of coupled residents. Data from participants at the eighth location contributed to our overall understanding of couples’ experiences.

Table 1.

Select Facility and Resident Characteristics by Settinga

| Caroline Place | Feld House | Garden House | The Highlands | Meadowvale | Oakridge Manor | Peachtree Hills | Pineview | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean census/licensing capacity | 33/42 | 22/47 | 16/18 | 78/100 | 52/66 | 42/55 | 49/75 | 66/68 |

| Ownership | Corporate | Nonprofit religious foundation | Private | Corporate | Corporate | Corporate | Private | Corporate |

| Monthly fee range | $2,700 to $3,900 | $2,700 to $4,300 | $2,550 to $2,900 | $2,800 to $3,500 | $2,100 to $4,800 | $2,700 to $5,295 | $2,645 to $3,145 | $2,986 to $4,195 |

| Location | Urban | Suburban | Suburban | Suburban | Suburban | Urban | Urban | Small Town |

| Dementia care unit | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Resident race | Most white | All white | Most white | Most white | Most white | All African American | Most white | Most white |

| Resident age range | 59–100 | 52–99 | 65–96 | 78–98 | 42–100 | 54–103 | 65–103 | 73–98 |

| Number of married couples | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| Number of unmarried couples | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

aData provided by the Executive Director.

At each site, we selected the executive director for an in-depth interview. Activity and care staff were purposively selected for their knowledge of resident relationships. We invited all residents with at least 3 months tenure and the cognitive ability to consent to participate in surveys. Nine married, three coupled, and 166 uncoupled residents completed surveys. For qualitative interviews, we initially selected residents for maximum variation in gender, health, tenure, marital status, race, and ethnicity. Consistent with GTM, as the study progressed, we made sampling decisions based on analytical grounds and our emerging findings (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). The 51 in-depth interview participants included four married and three coupled residents. Combined qualitative sources, including fieldnotes from participant observation and informal interviewing, yield in-depth data on 29 couples.

Data Collection

A team of 13, including the authors and trained sociology and gerontology researchers, collected data for 1 year in each setting using formal and informal interviewing and participant observation (see Table 2 for data collection activities). Field visits, varying by time of day and day of the week, occurred an average of approximately three visits per home per week and were detailed in field notes. Residents’ social interactions and relationships were the focus of these activities.

Table 2.

Data Collection Activities and Frequencies by Setting Activity and Number

| Caroline Place | Feld House | Garden House | The Highlands | Meadow- vale | Oakridge Manor | Peachtree Hills | Pineview | Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Executive director interviews | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Resident interviews | 4 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 9 | 6 | 13 | 51 |

| Staff interviews | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 24 |

| Resident surveys | 17 | 19 | 8 | 39 | 22 | 19 | 26 | 28 | 178 |

| Field visits | 153 | 131 | 47 | 197 | 126 | 178 | 125 | 210 | 1,167 |

| Observation hours | 485 | 396 | 154 | 580 | 397 | 578 | 379 | 621 | 3,590 |

Note: A total of 51 and 11 residents refused to participate in surveys and interviews, respectively.

Interviews with administrative and care staff inquired about resident life, including coresident and intimate relationships, married residents’ experiences, and relevant policies and practices. In-depth resident interviews addressed past history and the move to and life in AL, especially coresident relationships, including intimate ties. Surveys collected health and social network data (see Perkins et al., 2013). We interviewed coupled residents individually rather than conjointly. Qualitative interviews lasted 75 minutes on average and were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Prolonged participant observation, including informal interviewing, provided longitudinal data and opportunities to capture continuity and change. NVivo 10.0 facilitated storage, management, and coding of all qualitative data.

Analysis

As defined by Corbin and Strauss (2008), GTM involves a process of constant comparison; our data collection, hypothesis generation, and analysis occurred concurrently. A major strength of this approach is flexibility to address new findings and modify assumptions made a priori by researchers. Throughout this process, we used theoretical sampling and analytical memos, including diagrams, matrices, and charts, to inform data collection and analysis and guide emerging theory. All 13 team members participated in data collection and analysis. The higher level analysis reported in this article was led by the authors and informed by insights gained from the research team in weekly team meetings.

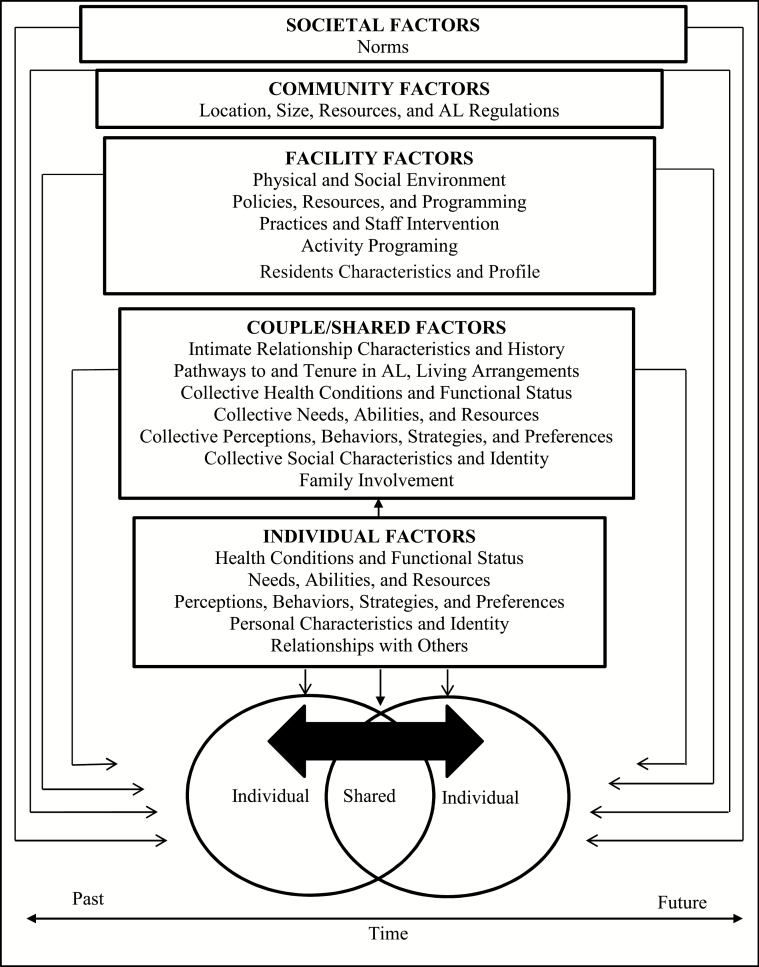

GTM uses three types of coding (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). Open coding involves line-by-line coding and consists of a process of identifying, labeling, and defining all concepts in interview transcripts and field notes pertinent to the study aims and grouping these according to their properties and dimensions. For example, a process we identified and labeled as “restricting interaction” was defined and elaborated along lines of duration, depth, and level of restrictiveness. Through axial coding, we linked initial categories and subcategories identified in open coding in terms of their properties and dimensions and identified various conditions, actions/interactions, and outcomes associated with these phenomena. During this stage, we identified factors that intersect to shape couples’ social careers, including facility practices, couples’ relationship history, and individual and collective health needs and functional abilities. As we continued to select, sort, and refine our categories, we used theoretical sampling to link these with relevant concepts in the literature (Morse & Field, 1995), including our own previous analysis (Kemp, 2008, 2012; Kemp et al., 2012, 2013). In the final stage of analysis, selective coding, we refined and integrated remaining categories until theoretical saturation was achieved and no new themes or relevant data emerged. Based on our analysis, we identified our core category (Corbin & Strauss, 2008), “reconciling individual and shared situations across time,” which is a central explanatory process that links all other concepts in our theoretical scheme (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Couples’ social careers in assisted living: Reconciling individual and shared situations across time.

Results

Reconciling Individual and Shared Situations

Couples’ social careers in AL were highly variable and involved the dynamic process of reconciling individual and shared situations across time, including needs, abilities, preferences, resources, and perceptions of past, present, and future. Intimate partners belonged to one another’s care convoys (Kemp et al., 2013). Table 3 provides select couple characteristics. As shown, all 26 married couples were in long-term unions with lengthy histories and established ways of relating. In contrast, the three unmarried couples met in AL. Despite variations in experiences, we observed general patterns in the ways couples reconciled individual and shared situations. Our analysis affirms the four couple types from the exploratory study (Kemp, 2008), provides evidence of four additional types (see Table 4), and documents changes to couples’ patterns over time.

Table 3.

Select Characteristics of Couples Sample, N = 29 (26 married and 3 unmarried)

| Characteristics | Mean | Min–Max |

|---|---|---|

| Woman’s age (years) | 87 | 75–103 |

| Man’s age (years) | 86 | 75–98 |

| Relationship duration | ||

| Marriage (years) | 61 | 40–69 |

| Dating (months) | 7 | 4–9 |

| AL Tenure (months) | 30 | 1–268 |

| N | % | |

| Living arrangement | ||

| Same apartment | 18 | 62 |

| Adjoining apartment | 3 | 10 |

| Separate apartment or floor | 4 | 14 |

| Wife in dementia care unit | 4 | 14 |

| Widoweda | ||

| Wife died | 7 | 27 |

| Husband died | 6 | 23 |

| Couples discharged for one spouse’s needsa | 2 | 12 |

| Spouses moved in at different timesa | 3 | 12 |

aOnly applicable to married couples.

Couples Typology

Below, we provide case examples illustrating each of the six couple types and identify the major factors shaping the patterns of reconciling individual and shared situations (see also Table 5) that define couples’ interaction patterns and, hence, social careers. As Figure 1 illustrates, at any given moment, a factor or intersecting set of factors can define couples’ individual and collective experiences. The relative influence of factors often changes as individual and shared situations evolve. Spouses’ or partners’ needs or behaviors can shift and redefine experiences as time passes and as they respond to present circumstances, often based on their perceptions of the past and anticipation of the future. In the following examples, we highlight continuity and change to demonstrate the dynamic nature of reconciling individual and collective situations.

Table 5.

Factors Influencing Couples’ Social Careers in Assisted Living

| Factor level | Description |

|---|---|

| Societal factors | |

| Norms | Norms governing married/unmarried couples and pertaining to gender and age affected couples’ reception. Among married couples, relationship norms, including those governing caregiving, often shaped dedication to care activities and living arrangements (i.e., remaining in the same setting). |

| Community factors | |

| Size, location, resources, and AL regulations | The size and location of the facility’s surrounding community influenced the availability of nearby health care resources, nursing homes, hospice, rehabilitation facilities, and other AL communities. Availability meant couples could visit one another if separated by illness or having relocation options if discharged. AL regulations provide parameters for facility policies. |

| Facility factors | |

| Physical environment | Facility size often affected availability of relationship partners. Dementia care unit availability facilitated asynchronous couples being in the same AL setting, but also meant physical separation for certain couples. |

| Social environment | Degree of tolerance for frailty, availability of support, complaints, and gossiping influenced resident experiences, including of couples. |

| Policies and resources | Discharge policies (often shaped by facility resources) affected whether couples could remain together with increased impairment and care needs. |

| Practices and staff intervention | Whether or not staff encouraged residents to spend time in common areas, attend activities and meals, and promoted social relationships affected opportunities for social interaction, particularly among couples. Staff intervention in intimate and social relationships was both proactive and reactive. |

| Activity programming | The availability of a range of activities allowed couples with different interests and abilities to have some independence from one another and engage with other residents. |

| Resident characteristics/profile | Resident characteristics, especially levels of impairment, affected levels of tolerance for fellow residents. The number of couples affected opportunities to socialize with other couples. Gender imbalance sometimes led to jealousy and in a few instances, created opportunities for infidelity. |

| Dyadic/shared factors | |

| Intimate relationship characteristics and history | Married couples in AL all had long-term relationships and past ways of relating that continued in AL and shaped daily life and often the negotiation of illness and decline among spouses. Unmarried couples met and dated in AL and lived in separate apartments. |

| Pathways to and tenure in AL | Couples’ synchronicity in health and need to relocate to AL affected experiences (see Kemp, 2008) and sometimes led to transitioning at different times. Being asynchronous often involved caregiving, which limited social interaction with others. Longer tenure sometimes meant time to adjust and become open to the idea of socializing with others, but the passage of time could lead to increasing frailty and isolation. |

| Living arrangements | Arrangements included living in the same or different apartment, floors, or sections of the AL community. These arrangements influenced couples’ interaction patterns with One another and others. |

| Collective health conditions and functional status | Couples’ health and functional status shaped their daily activities, socialization, and care needs. Those with greater collective limitations often were the most socially and physically isolated from each other and others. |

| Collective perceptions, behaviors, strategies, and preferences | The needs of one spouse often defined couples’ overall experiences. Couples’ collective abilities and resources, including for example, resources to pay for assistance such as a private care aide and the couples’ collective perceptions and treatment of other residents, including their interest in and willingness to socialize in AL, affected their overall engagement with others and involvement in AL life. In certain instances, individual spouses’ preferences were at odds, with spouse’s behaviors sometimes dominating a couple’s collective pattern. |

| Collective social characteristics and identity | Each couple had characteristics that shaped their identity as a couple both in terms of how the related to each other (e.g., loving couple) and others (e.g., social couple). Among unmarried couples identifying as a couple in AL led to being the target of gossip. |

| Family involvement | Availability of family involvement affected the level of support for one or both, such as facilitating social interaction or intervening in relationship problems. |

| Individual factors | |

| Health conditions, functional status, and resources | Individuals’ health conditions and functional status affected day-to-day well-being and care needs and abilities and shaped interest in interaction with others, including one’s intimate partner, and willingness and ability to participate in social life, including attending meals and activities. |

| Perceptions, behaviors, strategies, and preferences | Individuals’ perceptions and treatment of other residents, including their interest in and willingness to socialize in AL affected the couple’s individual and collective engagement with others. |

| Personal characteristics and identity | Each spouse/partner’s identity affected how they related to the other (e.g., loving spouse) and others (e.g., nice person). Often these identities were shaped by personal characteristics. |

| Relationships with others | The quality, quantity, and nature of individual spouses/partners’ relationships with others, particularly coresidents, affected their individual and shared social experiences in AL. Friendships were resources for coupled spouses, particularly with caregiving or loss of a spouse. Conversely, relationships with others led to jealousy and infidelity. |

Note: AL = assisted living.

Independent

Three couples, including one unmarried couple, were independent. They spent time together and helped one another, but enjoyed separate activities and relationships. Oakridge’s executive director explained, “We have couples where, ‘That’s for my wife, that’s not for me. She enjoys that, I don’t.’” The Riley’s represent this type. Independent throughout her life, Mrs. Riley was in her mid-forties when she married Mr. Riley, who, now in his 90s, was a few years her senior and had three children from a previous marriage. Their marital career was characterized by love and affection. They lived together at home for nearly 40 years, until Mrs. Riley fell ill and was hospitalized. Mr. Riley, who had dementia and a heart condition and was unable to live alone, moved to AL. Mrs. Riley subsequently returned home from the hospital but, after living apart for several months, reluctantly left her beloved home to join her husband at Meadowvale because she “didn’t want to live without him.” Although the couple continued their “loving and affectionate” ways, with Mrs. Riley trying to keep her husband “healthy and happy,” her initial unhappiness affected her social engagement. She explains, “I didn’t [make an effort to know people] when I first came. I was miserable . . . I didn’t want to be here in the first place. I wanted to go back to my home.”

Over time, Mrs. Riley’s attitude changed and she joined her husband in being friendly to fellow residents. Mrs. Riley noted, “I get along with all the residents” and “Mr. Riley goes out and talks to everybody.” Historically an outgoing couple, they began spending most of their time out of their apartment. They attended meals and special events together, but also had separate activities. He, a former minister, led a Sunday service and took on the role of comforting fellow residents. He liked exercise class and bingo; she preferred walking the halls and intellectually stimulating activities. Yet, these independent ways were unsustainable as Mr. Riley’s dementia progressed. She explained:

Sometimes I tell him, “I’ve got some things to do in here and I’ll be out in a little while.” Then I’ll go out and he’ll say, “Well, I walked up and down the halls and I looked everywhere for you, and I thought you had gone out.” And he is so sensitive that I have to be real careful or he will start to cry and he never did that before. . . Now, if I disagree with him about anything, he will say, “Well I’m going to my room.”

Mr. Riley’s individual situation (dementia) affected their shared circumstances (managing his changing abilities and emotions), placing the couple on the cusp of being restricted-independent.

Restricted-independent

Data affirm the existence of restricted-independent couples among married residents, where one spouse socially limited the other. Caregiving constrained 12 of the 13 restricted-independent couples, structuring their days and interactions.

Caregiving Spouse

Married for 63 years, the Russell’s are representative. For them and three other couples, the availability of a dementia care unit (DCU) was a facility factor that enabled being together despite asynchronous needs. The Russell’s moved to Highlands 5 years earlier upon Mrs. Russell’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis. Each morning Mr. Russell, essential to his wife’s care convoy, left his AL apartment to wake, dress, toilet, and bathe her in the DCU. She then “remained with him in AL during her waking hours,” eating meals and attending activities. Field notes detail a conversation with Mr. Russell: “When they first moved in everyone knew everyone else, spoke to each other, and helped each other.” Over time, the home’s culture changed. Mr. Russell noted current residents have “no compassion” including “southern belles” who were “spoiled brats.” Alongside this change, Mrs. Russell’s decline led to the administration’s decision that “Mrs. Russell couldn’t eat in the AL dining room any longer because she was a messy eater and he had to cut up her food.” Intended to accommodate other residents’ preferences, according to Mr. Russell, the restriction “changed everything.” Highlands’s administrator noted, “Assisted living residents don’t want to see DCU residents. They don’t want them around. I think it’s too real. I think maybe it’s too—the reality is just too close. And, out of sight, out of mind.”

Mr. Russell continued caregiving, but the couple spent the majority of time in the DCU. He limited his time in AL to meals and bedtime but was perpetually tired. He began taking sleeping pills, explaining, “I have things on my mind,” and worries about his wife “all the time.”

Ultimately, the administration discharged Mrs. Russell, saying she needed “nursing home care,” and ending the Russell’s social career at Highlands. The couple relocated to a nearby AL community with more lenient policies. Another couple also was discharged because of one spouse’s needs. Georgia AL regulations require that facilities staff beyond minimum required ratios to meet the ongoing health, safety and care needs of residents; some facilities choose the option of discharging residents with increased needs.

Restrictive Spouse

In the exploratory couples study (Kemp, 2008), restricted-independent spouses were limited by caregiving. In this study, for one couple, the Warren’s, the wife placed social limitations on the husband, reflecting past ways of relating within their 62-year marriage. Collective health problems prompted the move of the “dour” Mrs. Warren and her husband, whom she and others described as having a “sweet disposition,” to Meadowvale, where they had adjoining apartments. Mr. Warren had dementia but was reasonably mobile and did not need constant oversight. Mrs. Warren was arthritic and had macular degeneration. Staff described her as keeping him on “a short leash.” Researchers observed “she hardly let him move without her,” often restricting social interactions. Field note data describe common occurrences: “Mrs. Warren got off the elevator and asked Mr. Warren where he had been. She complained that every morning she had to come down and get him. He was quiet as she scolded him”; and “Mr. Warren stopped to talk but Mrs. Warren kept saying, ‘Come on, Richard,’ so they went off to their room.” According to a staff member, “She doesn’t want anyone talking to him. She’s very jealous. If he speaks to anyone, she gets very upset.” Mrs. Warren vacillated between being “extremely sweet” and “putting him down” or “yelling at Mr. Warren” and telling others, including coresidents, that he had dementia and drove her “crazy.” Their son remarked, “She is always telling him what to do.” Mr. Warren was mild-mannered and ever-compliant. He routinely attempted to be affectionate and include his wife in activities, but, as a researcher noted, “she always rebuffs his advances.” Mrs. Warren fell several times, prompting relocation to a rehabilitation facility; each time Mr. Warren accompanied her, at considerable cost, depleting their collective resources. During the last rehabilitation, they released their apartments at Meadowvale and subsequently moved to a less expensive facility.

Inter-reliant

We identified the existence of inter-reliant couples who rarely were apart. Oakridge’s administrator described one such couple, noting, “They do everything together. They’re just like two peas in a pod. The relationship is driven by ‘whatever we do, as long as we’re together.’” Describing the same married couple, a coresident commented, “They do everything, everything together. I think I’ve only ever seen them apart two or three times.” We confirmed that inter-reliant couples can be socially engaged or self-isolated, but also identified a new type, socially marginalized.

Socially Engaged

This category included one married couple and two of the three unmarried couples, who spent most of their time together at meals and activities. Ms. Walters and Mr. Lionel, both divorced, began dating shortly after Ms. Walters moved to Oakridge. Mr. Lionel explained, “They assigned her to our table and I met her there and I liked her and started seeing her.” Ms. Walters offered, “I just fell in love with that man. You know, I didn’t even love my husband like I love him.” The pair participated in facility life, attending exercises, outings, and other activities, but also spent time privately. Ms. Walters explained, “He’ll call me to come down [to his apartment] and look at a movie or something with him or listen to music.” They focused on their relationship rather than connections with coresidents, in part because of gossip. When asked about friendships, Ms. Walters commented, “Mr. Lionel takes up almost 100% of my time.” She explained, “I haven’t been able. I hadn’t had to be friends with these people here.” She also avoided a clique of widows who gossiped about their romance. One such widow spoke disapprovingly, perhaps jealously, about Mr. Lionel and Ms. Walters’ romance: “I was told that Mr. Lionel was lonely and wanted company, but I wasn’t ready for that. Now, just look at them.”

Similarly, the romance between the other unmarried inter-reliant couple, Margot and Willis, 12 years younger was the focus of gossip. A Peachtree resident explained: “I think it’s wonderful that Margot can be so happy and find somebody at 103 who wants to do things for her. I know lots of them think Margot and her boyfriend are just the silliest thing.” The thought of an older woman dating a “younger” man was not universally palatable. For these couples, ways of relating to one another and being the focus of gossip shaped their social career(s). In contrast, the other unmarried Oakridge couple, Ms. Tess and Mr. Baldwin, avoided scrutiny by sitting at separate tables, keeping their relationship private, and being an “independent” couple and by the relatively private location of their apartments, at the end of a hallway.

Self-isolated

Seven inter-reliant couples, all married, were self-isolated, including two former socially engaged couples. In their 90s and married for 67 years, the Schaus’s moved to an apartment in Peachtree Hills. Mrs. Schaus had moderate, advancing dementia; Mr. Schaus had congestive heart failure. A staff member explained their transition:

She’s got bad dementia. They came here with him totally mobile and really able to see after her, but he needed help with her. His heart condition progressed. He’s now on oxygen full time. They were always downstairs. They ate in the dining room [and] everything, you know. But now they stay in their apartment all the time. . .When they do come out she’s pushing him in a wheelchair. So it’s his physical condition, her mental condition.

This couple’s experience underscores how health synchronicity, functional ability, and facility practices can shape individual and shared social experiences. Although collective health needs prompted the move, his decline, paired with the practice of letting residents dine in their rooms (not routinely encouraged in AL or permitted without a fee), resulted in individual and shared isolation lasting until his death.

Socially Marginalized

One couple, the Horton’s, represent the previously unidentified socially marginalized inter-reliant category. They relocated to Highlands when their collective cognitive decline prevented living independently. Despite the couple’s advanced dementia, their children were “in deep denial about their parents’ level of dementia” and consequently prevented a move to the DCU. The couple always interacted with each other and their private care aide, who regularly brought them to common spaces. Speaking to Mr. Horton, the aide explained, “Well we wanted to sit here and see people—get out of our room.”

Despite being in public areas, the Horton’s were “ignored” and “avoided” and the object of “negative comments and reactions” because of their disruptive behaviors and others’ lack of tolerance. A fellow resident identified the Horton’s, particularly Mr. Horton, as residents she avoids, commenting: “He makes me so mad. I mean I hollered at him the other day, ‘Shut up!’ I know he’s sick, but that doesn’t excuse him.” During sing-along activities, Mr. Horton had the “annoying” habit of repeating the same song. He occasionally had outbursts of “yelling,” prompting staff intervention. Most residents believed the Horton’s should be in the DCU; one noted, “They are just pitiful and sad to watch.”

All homes permitted hospice workers, private care aides, and other externally provided care, which facilitated staying in AL as needs escalated. These practices were not always well received by other residents. The Horton’s aide was their “ticket to freedom” from the confines of their apartment. For this couple and three others, an aide extended their ability to age in place. Private aides also limited privacy. Mrs. Horton often complained about “too many people,” referring to their aide’s presence. The Horton’s individual and shared impairment levels and private aide, enabled by their financial resources, influenced theirs social careers. Facility influences included intolerance among coresidents and the practices of intervention in resident interactions and permitting aides.

Coexistent

The present analysis identified a new couple interaction type, coexistent, with two variants. For these couples, both married, spouses resided together but had minimal interaction. They differed in cognitive and physical abilities, marital history, and social encounters.

Socially Marginalized

In their 80s and married for nearly 65 years, the Rudy’s shared an Oakridge apartment; their children resisted moving them to the DCU. Mr. Rudy was blind, in a wheelchair, and rarely spoke or was spoken to by fellow residents, including his wife. Staff routinely placed Mrs. Rudy near her husband, but her dementia caused her to wander, forget she was married, or wish to be unmarried. Mrs. Rudy occasionally became agitated or emotionally distraught as the following exchange with a researcher attests:

She held my hand as she wept and said things like, “I don’t belong here.” “I want to go home.” “They don’t understand me here – I’m in a terrible condition, do you know that?” “I need to call my mother – she doesn’t know I’m here.” And then she proceeded to say that she is “tired of her husband.”

Although Mrs. Rudy talked to and was occasionally consoled by residents with patience or cognitive impairment, most ignored or made fun of her. Mr. Rudy was even more isolated and shunned by residents. Select residents felt sorry for the couple, including Mr. Tyler, who said, “They don’t seem to know what’s going on and no one really pays them, especially Mr. Rudy, much attention.”

Oakridge’s practice of placing residents with heavy care needs in common areas and encouraging activity participation prevented this couple’s complete isolation. When the study began, they had their meals in a private dining area, but eventually dined in the DCU. These transitions, facility responses to complaints about Mr. Rudy’s unappealing eating behaviors, reinforced their marginalization.

Self-isolated

Unlike the Rudy’s, Mr. and Mrs. Grayson, married 65 years and in their 80s, isolated themselves at Peachtree Hills. He had dementia, used a wheelchair, and spent his time, day and night, in bed. She had a degenerative disorder that limited mobility and, when not at doctors’ appointments or therapy, she sat and slept in a recliner in their separate living area. Mrs. Grayson frequently told researchers she wished she “could live apart from him,” explaining his “mental problems” led him to remain in bed for several days without eating, bathing, or taking medication. She resisted asking staff for help for fear he might be abusive towards them and implied a history of aggression. Although seemingly depressed and overwhelmed, she received little help from her sons. The couple’s isolation meant little support from others in the AL community. Mrs. Grayson was hospitalized twice and died in a hospice facility. After her death, a care worker observed that Mr. Grayson was “much better” and “getting up and eating.” She noted: “It’s too bad when couples get to that point.”

Negotiating Relationship Transitions in AL

Above we identified several transitions affecting couples in AL, including health declines and changes to interaction patterns. Additional transitions, including infidelity and widowhood, factor into couples’ reconciliation processes and social careers.

Infidelity

In two cases, both involving dementia, marital indiscretions occurred between husbands and widowed residents resulting in marital problems and staff and family intervention. At Oakridge Manor, a past indiscretion with another resident who was friends with both spouses was an ongoing challenge. Destiny, a staff member explained:

Mrs. Story went out of town with her daughter and left Mr. Story. She comes back and finds Mr. Story and Ms. Mundy in the bed together . . . she was upset with both, so from that stemmed a whole bunch of stuff where she didn’t forget.

Thereafter, Mrs. Story occasionally yelled at Mrs. Mundy or her husband and once “punched him right in the face.” Sometimes, Ms. Mundy, also with dementia, sat between the couple, angering Mrs. Story and leading Destiny to re-direct Ms. Mundy: “You sit on the other side and let her sit by her husband. . .While she’s in here, you’re going to respect her. That’s her husband.” Oversight was a continuous process. Indiscretions were known and gossiped about by residents and staff long after occurrences.

Widowhood

Twelve married residents became widowed in AL. Although Mr. Grayson improved upon his wife’s death, widowhood typically was associated with being depressed and “lost.” Mrs. Wellington, who “always stayed in her Caroline Place room with her husband,” continued doing so after his death, vowing she did not “want to live without him.” A care worker described family intervention: “I’m glad they have a private care aide for her because I remember her saying once he died maybe she would just throw herself down the steps.” Her husband encouraged interaction with coresidents. His death led to isolation.

Oakridge’s executive director described widowhood as “an easier transition” for those in AL compared to those widowed prior to moving. Observational data confirm that the communal environment can provide social opportunities and support. Staff routinely talked about “looking out for” recently widowed residents, as did certain residents. For instance, Mrs. Bailey’s relationship with tablemate Alice proved invaluable after losing her husband of 65 years. Alice listened and provided comfort when Mrs. Bailey “broke down.” Altruistically, Alice began waking early to attend breakfast with Mrs. Bailey because “she needed” her.

In relationships involving considerable decline and spousal caregiving, the surviving spouse’s social experiences dramatically altered. Four spouses provided significant end-of-life care, including Mr. Church. The couple moved to Pineview for her needs and he moved after out her death.

At the opposite end of the spectrum were residents with dementia who lost a spouse. Having dementia complicated widowhood, particularly regarding comprehension of a spouse’s absence. Several residents oscillated between recognizing the loss as final and creating alternative explanations, including Mrs. Thomas who noted that her husband “left the facility” and hoped “he’d move back soon.”

Discussion

This article extends research on couples and social relationships in later life, particularly in AL. Findings demonstrate the strengths and burdens of late-life couplehood. We affirm and expand previously identified interaction patterns. Our core category, “reconciling individual and shared situations across time,” highlights interpersonal and microlevel processes and the interconnectedness of couples’ lives, which was simultaneously beneficial and detrimental. Benefits included companionship, support, and affection. Caregiver burden, feeling defined by one’s spouse, and having limited choices were among the detrimental outcomes.

As with uncoupled residents, couples’ social careers in AL began with relocation, which typically was prompted by health decline, shifting dependence patterns, and an inability or reluctance to maintain former living situations. For married couples, the synchronicity of spouses’ need for AL, availability of material, emotional, and social resources, relationship history and dynamics, as well as perceived social norms and expectations, shaped the move (see also Kemp, 2008). Our current analysis situates couples within other broad influences and identifies the multilevel factors affecting their experiences. Our conceptual model provides an important framework and basis for future research that can be modified to account for range of contextual factors (e.g., in non-AL settings and in locations outside of Georgia and the United States).

In the present study, AL-level factors include policies, practices, resources, and social environment that were influenced by surrounding cultural and geographical factors. We confirm that facility culture changes over time and influences residents’ experiences (Morgan et al., 2014; Perkins, Ball, Whittington, & Hollingsworth, 2012). Highlands transitioned from supportive to intolerant for cognitively impaired Mrs. Russell. This scenario, including shunning and social distancing, particularly in response to cognitive impairment and other frailties, affects all residents (Sandhu et al., 2013). Yet, couples’ linked lives means the treatment of one affects both. Findings confirm that care settings are variable and have modifiable structures and processes that simultaneously can “promote and protect against stigma” (Zimmerman et al., 2014, p. 10).

In AL, couples negotiate their relationships in the presence of others, which both positively and negatively influences social careers. Among asynchronous couples, for example, research shows health problems in frailer spouses can negatively affect healthier spouses’ mood, but outside social support can be a buffer (Roper & Yorgason, 2009). Socially isolated, marginalized, or limited couples are without such supports. For those in low-quality relationships, being in AL limited one spouse’s ability to avoid the other, particularly when opportunities to socialize with others were not sought (e.g., Graysons).

AL residents may require assistance developing relationships to fit their needs and preferences. Coresidents, staff, and family members play important roles. There may be a taken-for-granted assumption that couples have one another and do not need or want external relationships. In a recent study of residents’ health discussion networks in nursing homes and AL, Abbott, Prvu Bettger, Hanlon, and Hirschman (2012, p. 791) concluded that married residents “have a trusted confidant with whom to discuss health concerns.” Yet, the frailty of those in the present study and the range of marital quality meant coupled residents could not always rely on their intimate partners for this or other types of support.

Fellow residents may prove exceedingly important confidantes, companions, and even friends to coupled residents in AL. As previously found, supportive coresident relationships can develop through thoughtful activity programming, seating assignments, and interventions (Kemp et al., 2012; Sandhu et al., 2013). AL residents, particularly those with functional limitations, have been found to derive significant psychological benefits through social engagement and interpersonal connections within facilities (Jang, Park, Dominguez, & Molinari, 2014).

Having a friend as a confidante can buffer negative health outcomes associated with marital transitions, including widowhood (Bookwala, Marshall, & Manning, 2014). Coresidents represent social partners and potential confidantes, especially when one’s spouse is ill or dies. Research should further investigate these losses, particularly as AL increasingly is a site for end-of-life care and death (Ball et al., 2014).

Cognitively impaired spouses may require additional support when they become widowed, but cannot remember why they are sad or do not recognize the loss. Practices such as reinforcing the reality of a death may be ill-advised and only cause further pain. While not dismissing the importance of allowing individuals to grieve, caregivers can develop ways to promote lasting positive emotional experiences. Activity programming, for instance, can create positive experiences for cognitively impaired residents (Morgan & Stewart, 1997). Alzheimer’s patients can sustain a mood long after they forget the event that caused the emotion (Guzmán-Vélez, Feinstein, & Tranel, 2014).

The AL social environment, with the potential for other partners, induced jealousy and marital infidelity among some couples. Ageist assumptions regarding the asexuality of older adults (i.e., they are not sexual beings) and romantic views of later-life relationships (i.e., that they are unproblematic and happy) limit research questions and hence knowledge and assistance. These matters require attention and imply the potential value of counseling or intervention, particularly given that over a quarter of AL residents have depression (Caffrey et al., 2012).

High impairment levels and gender imbalance in AL explain the scarcity of unmarried couples in our sample. Yet, their inclusion is meaningful owing to the minimal research on dating relationships in old age (Alterovitz & Mendelsohn, 2013). These couples’ experiences show that intimate relationships can develop in late life and in AL. Unmarried couples were gossiped about, particularly women, indicating different cultural scripts apply to older men and women and married and unmarried couples.

Some residents had intimate relationships outside AL, including two same-sex relationships. Although beyond our scope, future research should include the full array of living arrangements and partnerships. Despite this and other limitations, including a small sample of heterosexual non-Hispanic Black and White couples and settings in one state, our work illustrates the complexity and range of later-life couples’ intimate and social lives. It has implications for supporting coupled individuals more broadly and illuminates pathways for future work. Intimate and social relationships are critical to health and well-being and require ongoing attention as they grow increasingly diverse with shifting preferences, norms, and laws and the ever-changing social and demographic landscape in the United States and beyond.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health (R01 AG030486-01A1 to M. M. Ball).

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to those who participated in the study. Special thanks to Carole Hollingsworth for her hard work, dedication, and invaluable contributions, and to Elisabeth O. Burgess and Frank J. Whittington, for their insights, feedback, and support. Thank you to Mark Sweatman, Michael Lepore, Emmie Cochrane Jackson, Shanzhen Luo, Ailie Glover, Yarkasah Paye, Vicki Stanley, Amanda White, Terri Wylder, Navtej Sandhu, Karuna Sharma, and Sophie Carrssow for their research assistance.

References

- Abbott K. Prvu Bettger J. Hanlon A., & Hirschman K (2012). Factors associated with health discussion network size and composition among elderly recipients of long term services and supports. Health Communication, 27, 784–793. doi:10.1080/10410236.2011.640975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama H. Elliot K., & Antonucci T. C (2000). Same-sex and cross-sex relationships. In Markson E. W., Hollis-Sawyer L. A. (Eds.), Intersections of aging: Readings in social gerontology (pp. 252–262). Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Alterovitz S. S. R., & Mendelsohn G. A (2013). Relationship goals of middle-aged, young-old, and old-old internet daters: An analysis of online personal ads. Journal of Aging Studies, 27, 159–165. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2012.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball M. M. Kemp C. L. Hollingsworth C., & Perkins M. M (2014). “This is our last stop”: Negotiating end-of-life transitions in assisted living. Journal of Aging Studies, 30, 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2014.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball M. M., & Perkins M. M (2010). Overview of research. In Ball M. M. Perkins M. M. Hollingsworth C., & Kemp C. L. (Eds.), Frontline workers in assisted living (pp. 49–68). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berg C. A., & Upchurch R (2007). A developmental-contextual model of couples coping with chronic illness across the adult life span. Psychological Bulletin, 133, 920–954. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.133.6.920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg C. A. Wiebe D. J. Butner J. Bloor L. Bradstreet C. Upchurch R., & Patton G (2008). Collaborative coping and daily mood in couples dealing with prostate cancer. Psychology and Aging, 23, 505–516. doi:10.1037/a0012687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birditt K. S. Newton N., & Hope S (2014). Implications of marital/partner relationship quality and perceived stress for blood pressure among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69, 188–198. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbs123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookwala J. (2014). Spouse health status, depressed affect, and resilience in mid and late life: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 50, 1241–1249. doi:10.1037/a0035124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookwala J., & Jacobs J (2004). Age, marital processes, and depressed affect. The Gerontologist, 44, 328–338. doi:10.1093/geront/44.3.328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookwala J. Marshall K. I., & Manning S. W (2014). Who needs a friend? Marital status transitions and physical health outcomes in later life. Health Psychology, 33, 505–515. doi:10.1037/hea0000049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge S., & Street D (2010). Advantage and choice: Social relationships and staff assistance in assisted living. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65, 358–369. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbp118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffrey C. Sengupta M. Park-Lee U. Moss A. Rosenoff E., & Harris-Kojetin L (2012). Residents Living in Residential Care Facilities: United States, 2010. NCHS Data Brief, 91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J., & Strauss A (2008). Basics of qualitative research (3rd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Dassel K. B., & Carr D. C (2014). Does dementia caregiving accelerate frailty? Findings from the Health and Retirement Study. The Gerontologist. doi:10.1093/geront/gnu078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone J. W. (1995. a). Elderly married persons living in long term care institutions: a qualitative analysis of feelings. Ageing and Society, 15, 493–513. doi:10.1017/S0144686X00002877 [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone J. W. (1995. b). Marital perceptions of elderly persons living or having a spouse living in a long-term care institution in Canada. The Gerontologist, 35, 52–60. doi:10.1093/geront/35.1.52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán-Vélez E. Feinstein J. S., & Tranel D (2014). Feelings without memory in Alzheimer Disease. Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology, 27, 117–129. doi:10.1097/WNN.0000000000000020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppmann C., & Gerstorf D (2009). Spousal interrelations in old age--a mini-review. Gerontology, 55, 449–459. doi:10.1159/000211948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang Y. Park N. S. Dominguez D. D., & Molinari V (2014). Social engagement in older residents of assisted living facilities. Aging and Mental Health, 18, 642–647. doi:10.1080/13607863.2013.866634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn R. L., & Antonucci T. C (1980). Convoys over the life course: A life course approach. In Baltes P. B., Brim O. (Eds.), Life span development and behavior (pp. 253–286). New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp C. L. (2008). Negotiating transitions in later life: Married couples in assisted living. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 27, 231–251. doi:10.1177/0733464807311656 [Google Scholar]

- Kemp C. L. (2012). Married couples in assisted living: Adult children’s experiences providing support. Journal of Family Issues, 33, 639–661. doi:10.1177/0192513X11416447 [Google Scholar]

- Kemp C. L. Ball M. M. Hollingsworth C., & Perkins M. M (2012). Strangers and friends: Residents’ social careers in assisted living. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67, 491–502. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbs043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp C. L. Ball M. M., & Perkins M. M (2013). Convoys of care: Theorizing intersections of formal and informal care. Journal of Aging Studies, 27, 15–29. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2012.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korporaal M. van Groenou M. I. B., & van Tilburg T. G (2008). Effects of own and spousal disability on loneliness among older adults. Journal of Aging & Health, 20, 306–325. doi:10.1177/0898264308315431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korporaal M. van Groenou M. I. B., & van Tilburg T. G (2013). Health problems and marital satisfaction among older couples. Journal of Aging and Health, 25, 1279–1298. doi:10.1177/0898264313501387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan L. A. Rubinstein R. L. Frankowski A. C. Perez R. Roth E. G. Peeples A. D. … Goldman S (2014). The facade of stability in assisted living. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69, 431–441. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbu019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D. G., & Stewart N. J (1997). The importance of the social environment in dementia care. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 19, 740–761. doi:10.1177/019394599701900604 [Google Scholar]

- Morse J. M., & Field P. A (1995) Qualitative research methods for health professionals. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Moss S. Z., & Moss M. S (2007). Being a man in long term care. Journal of Aging Studies, 21, 43–54. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2006.05.001 [Google Scholar]

- Park N. S. (2009). The relationship of social engagement to psychological well-being of older adults in assisted living facilities. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 28, 461–481. doi:10.1177/0733464808328606 [Google Scholar]

- Peek M. K. Stimpson J. P. Townsend A. L., & Markides K. S (2006). Well-being in older Mexican American spouses. The Gerontologist, 46, 258–265. doi 10.1093/geront/46.2.258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins M. M., Ball M. M., Kemp C. L., Hollingsworth C. (2013). Social relationships and resident health in assisted living: An application of the Convoy Model. The Gerontologist, 53, 495–507. doi:10.1093/geront/gns124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins M. M. Ball M. M. Whittington F. J., & Hollingsworth C (2012). Relational autonomy in assisted living: A focus on diverse care settings for older adults. Journal of Aging Studies, 26, 214–225. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2012.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roper S. O., & Yorgason J. B (2009). Older adults with Diabetes and Osteoarthritis and their spouses: Effects of activity limitations, marital happiness, and social contacts on partners’ daily mood. Family Relations, 58, 460–474. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2009.00566.x [Google Scholar]

- Sanders S., & Power J (2009). Roles, responsibilities, and relationships among older husbands caring for wives with progressive dementia and other chronic conditions. Health & Social Work, 34, 41–51. doi:10.1093/hsw/34.1.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu N. Kemp C. L. Ball M. M. Burgess E. O., & Perkins M. M (2013). Coming together and pulling apart: Exploring the influence of functional status on co-resident relationships in assisted living. Journal of Aging Studies, 27, 317–329. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2013.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street D., & Burge S. W (2012). Residential context, social relationships, and subjective well-being in assisted living. Research on Aging, 34, 365–394. doi:10.1177/0164027511423928 [Google Scholar]

- Street D. Burge S. Quadagno J., & Barrett A (2007). Salience of social relationships for resident well-being in assisted living. Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62, S129–S134. doi:10.1093/geronb/62.2.S129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompkins C. J., Ihara E. S., Cusick A., Park N. S. (2012). “Maintaining connections but wanting more:” Continuity in familial relationships among assisted living residents. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 55, 249–261. doi:10.1080/01634372.2011.639439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker R. B., & Luszcz M. A (2009). The health and relationship dynamics of late-life couples: A systematic review of the literature. Ageing and Society, 29, 455–480. doi:10.1017/S0144686X08007903 [Google Scholar]

- Warner D. F., & Kelley-Moore J (2012). The social context of disablement among older adults: Does marital quality matter for loneliness? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53, 50–66. doi:10.1177/0022146512439540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorgason J. B. Roper S. O. Sandberg J. G., & Berg C. A (2012). Stress spillover of health symptoms from healthy spouses to patient spouses in older married couples managing both Diabetes and Osteoarthritis. Families Systems & Health, 30, 330–343. doi:10.1037/a0030670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, S., Dobbs, D., Roth, E. G., Goldman, S., Peeples, A. D., & Wallace, B. (2014). Promoting and protecting against stigma in assisted living and nursing homes. The Gerontologist. Advanced online publication. doi:10.1093/geront/gnu058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]