Abstract

Purpose of this study:

To characterize illness perceptions among persons with mild cognitive impairment (PWMCI) and their family care partners, and to examine whether PWMCI’s and their family care partners’ illness perceptions were associated with their own, as well as the other member of the dyad’s, emotional reactions to MCI.

Design and Methods:

This cross-sectional study of PWMCI and their family care partners (n = 60 dyads) used patient and relative versions of the Revised Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ-R) to assess metacognitive and emotional features of illness perception in MCI along 5 dimensions of perceived: seriousness of potential consequences, personal controllability, timeline, fluctuation (cycling) of symptoms, and illness coherence (clear vs. confusing).

Results:

As compared to family members, PWMCI perceived MCI to be less potentially serious and to be more within their personal control, but dyads otherwise shared similar perceptions of MCI. Among PWMCI, perceived seriousness of the potential consequences of MCI was the only dimension to be significantly correlated with emotional distress. For family members, increased MCI-related emotional distress was significantly associated with perceptions of MCI as potentially serious, permanent, or confusing. A dyadic analysis using APIM showed that MCI-related emotional distress, in both PWMCI and family members, was linked to the PWMCI’s perception of the seriousness of MCI.

Implications:

MCI-related education and support should be tailored for both the PWMCI and family member audiences, while acknowledging interdependence of illness perceptions within family units. Tailored information and support will be critical in managing MCI going forward, as illness perceptions are likely key factors on which individuals will plan for the future or base medical decisions.

Keywords: Preclinical dementia, Illness representation, Caregiving, Health beliefs

The clinical and public health significance of early detection and prevention of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has led to increasing focus on individuals at heightened risk for dementia, whether by virtue of biomarker status or by the clinical expression of changes in cognition. Regarding the latter, mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is widely regarded as a clinical syndrome that represents an intermediate state between normal cognitive aging and dementia (Petersen et al., 2001). Although persons with MCI (PWMCI) are at increased risk of progressing to dementia relative to other individuals of the same age, continued cognitive decline is not inevitable and research shows that nearly half over those diagnosed with MCI in clinic settings will continue to function above the threshold for dementia within 5 years of their diagnosis (Espinosa et al., 2013; Mitchell & Shiri-Feshki, 2009). In the absence of robust and widely accessible predictors of clinical course, those affected by MCI may experience considerable uncertainty regarding the possibility of conversion to dementia.

Concerns about the heightened risk of dementia associated with MCI extend beyond the individual at risk to also impact immediate family members (Seeher, Low, Reppermund, & Brodaty, 2013; Springate & Tremont, 2014). As potential “caregivers-to-be,” family members of PWMCI have been noted to begin engaging in caregiving type activities (Garand, Dew, Eazer, DeKosky, & Reynolds, 2005; McIlvane, Popa, Robinson, Houseweart, & Haley, 2008) and are likely to be forming thoughts and feelings about what MCI means to them. These thoughts and feelings, referred to as illness perceptions (Leventhal, Brissette, & Leventhal, 2003), may be concordant, discordant, or overlap in complex ways with those of the affected individual. Understanding how PWMCI and their family care partners, as dyads, perceive and emotionally respond to MCI is important because MCI-related illness perceptions may influence how those affected cope with the diagnosis (Roberto, Blieszner, McCann, & McPherson, 2011) and make subsequent medical and other important life decisions.

The purpose of this study was to characterize MCI-related illness perceptions among MCI care dyads (affected persons + family care partners) and to examine whether PWMCI’s and their family care partners’ illness perceptions were associated with their own, as well as the other member of the dyad’s, emotional reactions to MCI.

Background

Illness Perceptions in MCI

Regardless of the disorder, when one receives a diagnosis, one begins to form thoughts and feelings about one’s illness. Leventhal’s Common Sense Model of Illness Representation refers to such perceptions as mental representations of illness and regards their formation as a first, necessary step in mobilizing an adaptive response to a diagnosis or set of symptoms (Leventhal et al., 2003). Illness representations manifest as beliefs about the nature of one’s symptoms, as well as about the cause, controllability, timeline (e.g., limited, indefinite, cyclical), and seriousness (e.g., potential consequences for daily functioning, social relationships, and finances) of one’s illness (Leventhal et al., 2003). Another dimension of illness representation is coherence (Moss-Morris et al., 2002), which refers to whether one thinks about an illness or set of symptoms in a coherent way (Weinman, Petrie, Moss-Morris, & Horne, 1996), versus being confused or unclear about one’s condition. Together, illness coherence and beliefs about a disorder’s cause, timeline, controllability, and seriousness of consequences, have typically been conceptualized as cognitive dimensions of illness perception. In the context of MCI these perceptions reflect one’s thoughts about having a cognitive disorder and are therefore referred to in the current report as metacognitions.

While each of these metacognitions is likely of relevance to MCI care dyads, several studies suggest that illness coherence may be particularly important in this population. For example, uncertainty regarding MCI has surfaced as a dominant them in analyses of individual interviews (Beard & Neary, 2013; Roberts & Clare, 2013) and focus groups (Frank et al., 2006) within samples of PWMCI. Although most research in this area has focused on PWMCI or care partners as individuals, concerns about uncertainty have also emerged in qualitative interviews involving both PWMCI and their care partners, (Samsi et al., 2014) as well as in research focusing on married couples in which one spouse has MCI and the other is striving to understand the syndrome’s manifestations (Blieszner, Roberto, Wilcox, Barham, & Winston, 2007). Interestingly, investigators have suggested that ambiguity concerning MCI may be associated with psychological distress (Beard & Neary, 2013). While the relationship of illness coherence to emotional upset in MCI has not been established, such an association would be consistent with the illness representation literature. In that field of study, emotional representations of illness have been operationalized as the perceived psychological distress associated with a health threat (Weinman et al., 1996) and are posited to be processed in parallel with the above-described cognitive dimensions of illness perception.

Emotional Distress in MCI Care Dyads

Investigations focused on the emotional distress associated with MCI have revealed mixed results. For example, focus groups with persons living MCI document such individuals to experience fear and embarrassment (Frank et al., 2006), and qualitative interviews have revealed individuals with MCI to voice fear (Beard & Neary, 2013) and anxiety (Samsi et al., 2014). Formal assessment of depressive symptoms, life satisfaction, and quality of life by McIlvane and colleagues (2008) revealed normal levels of psychological well-being in a sample of 46 PWMCI. More recently, low levels of emotional distress were also reported in Lin and colleagues’ (2012) study of 30 PWMCI.

Studies of emotional distress in family care partners of those with MCI have also shown conflicting results. A recent report described low levels of psychological distress in 278 care partners of PWMCI (Seeher et al., 2014). Earlier reports based on smaller samples documented low (e.g., Springate & Tremont, 2014) or moderate rates of elevated depressive symptoms among MCI care partners (Blieszner & Roberto, 2010; Garand et al., 2005), and a pooled analysis of data from six studies of this population found a depression prevalence rate of 23% (Seeher, Low, Reppermund, & Brodaty, 2013). Only one study has found marked emotional distress in MCI care partners (Lu & Haase, 2009). Two studies within this body of work found that psychological well being among MCI care partners was not significantly related to PWMCI’s symptom severity, while another report showed that severity of MCI symptoms did contribute to psychological distress on the part of MCI care partners (Seeher et al., 2013).

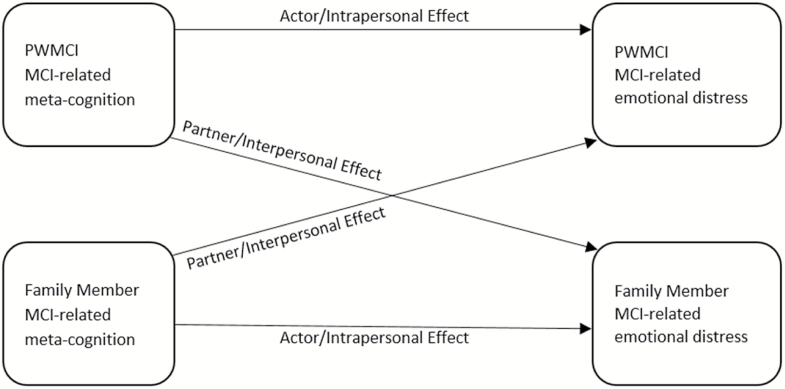

Together, the literature on PWMCI and family care partners’ reaction to MCI suggests that there is likely variability in emotional well being among MCI care dyads. While studies have examined objectively measured cognitive impairment as a potential correlate of such emotional reactions at the individual level (PWMCI or care partner), less is understood of how subjective perceptions about MCI impact the emotional status of MCI care dyads. For example, while it reasonable to hypothesize that MCI-related emotional distress may be positive correlated with illness coherence at the intrapersonal level within either member of the care dyads, it may be of equal importance to examine the cross partner or interpersonal effects of such dimensions of illness perception (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Actor–partner Interdependence Model Adapted from Cook and Kenny (2005). PWMCI = person with mild cognitive impairment.

This study, therefore, focused on determining how metacognitive dimensions of illness perception may be related to emotional distress within MCI care dyads at both the interpersonal and intra personal levels. We hypothesized that, among MCI care dyads, MCI-related emotional distress would be (a) inversely associated with perceived illness coherence, and (b) positively associated with ratings of the seriousness of MCI’s potential consequences. We hypothesized that these relationships would be present at both the interpersonal and intrapersonal levels.

Methods

This research was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Participants

A total of 63 MCI care dyads were referred to this study upon initial invitation by staff from the Memory Disorders Clinic and Alzheimer’s Outreach Center (AOC) of the University of Pittsburgh Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC). Of those 63, 3 dyads declined, and the remaining 60 MCI participants and their 60 family members provided written informed consent to this ancillary study of the ADRC. All participants with MCI met basic ADRC enrollment criteria (Lopez et al., 2000) and underwent multidisciplinary evaluations of their cognitive complaints including general medical histories and physical examinations, neurological assessments, psychiatric interviews, neuropsychological testing, and neuroimaging. In addition, those eligible for this study: (a) had an ADRC consensus diagnosis of MCI (subjective complaint plus either isolated impairment in verbal or visual memory; isolated deficit in a non-memory domain; or, mild deficits in multiple cognitive domains) within the past 12 months (Lopez et al., 2003); (b) had participated in a family diagnostic conference during which the MCI diagnosis was disclosed; (c) were at least 50 years of age; (d) were community-dwelling; and (e) identified a family member or kin-like friend (care partner) who also consented to the study. Eligible care partners: (a) were at least 18 years of age, and (b) had also participated in the family diagnostic conference. If more than one family member had participated in the diagnostic conference, the individual identified as the ADRC study partner of record was invited to participate in this study. The University of Pittsburgh ADRC procedure for diagnosing and disclosing an MCI diagnosis have been described previously (Lopez et al., 2003; Lingler et al., 2006). This study did not involve manipulating, observing, or analyzing diagnostic feedback sessions. A mean of 4.33 (SD = 3.64) months had lapsed between the time of the diagnostic feedback session and the interview for this study.

Measures

Illness Perception

The metacognitive and emotional components of illness perception were measured using subscales of the Revised Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ-R) as adapted for administration to PWMCI and their immediate family members. As recommended by Moss-Morris and colleagues (2002), the general IPQ-R phrasing, “my illness” was replaced with condition-specific terminology. Based on previous findings that individuals with MCI associate the syndrome with their symptom experience rather than a diagnostic label (Lingler et al., 2006), we replaced “my illness” with “my [or, my loved one’s] memory or thinking difficulties.” Cronbach’s alpha for the IPQ-R subscales ranged from 0.821 to 0.903 within this sample of PWMCI and family members, respectively.

Each of the IPQ-R subscales contains five to six items. Individual items consist of statements (e.g., “My memory or thinking difficulties will improve in time”) that are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Five subscales of the IPQ-R were administered to assess the respondent’s beliefs about the timeline, seriousness, and potential controllability of MCI, as well as illness coherence. Each of these metacognitive dimensions of illness perception was measured using a corresponding subscale, however, following the convention of IPQ-R administration, beliefs about the timeline of MCI were measured using two subscales, one assessing perceptions of illness as chronic (e.g., “My memory or thinking difficulties are likely to be permanent rather than temporary”) and the other cyclical (e.g., “I go through cycles in which my memory or thinking difficulties get better and worse”). A final subscale of the IPQ-R measured the emotional component of illness perception, with items assessing the degree of worry, upset or fear posed by MCI (e.g., “My memory or thinking difficulties do not worry me”). After reverse coding where applicable, items targeting each dimension of illness perception were summed to create subscale totals.

Procedure

Two trained data collectors together conducted home visits to ensure that administration of the patient and relative versions of the IPQ-R to participants with MCI and their care partners were separate, private, and simultaneous. Several steps were taken to ensure the validity of participants’ responses. First, data collection was conducted by interview rather than self-report. Second, respondents were provided with a large-font response card so that they could focus on the statement being read to them rather than on remembering the response options. Our protocol also required that the interview be discontinued if a participant could not answer, or required a repeated reading of, three consecutive items. Of note, no participants had to be withdrawn on that basis. Internal consistency analyses, presented above, further verified the reliability of participants’ responses.

To minimize participant burden, data describing the sample characteristics were abstracted from each consenting person’s ADRC record and verified as necessary at the time of the in-home interview. These data included basic sociodemographic information, MCI subtype (dichotomoized as amnestic or other), and duration of diagnosis (in months). To characterize the PWMCI’s global cognitive status and level of depressive symptomatology, the total scores for the Mini-Mental Status Exam score (MMSE; Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) and 17-item Hamilton depression rating scale (HDRS; Hamilton, 1960), were abstracted from each participant’s last annual ADRC visit. The MMSE is a 30-point measure of global cognitive status with scores of 24 and higher generally interpreted to reflect normal cognition (Folstein et al., 1975). Cronbach’s alpha for the MMSE has been reported at 0.91 in representative samples of older adults. The HDRS is an interview-based assessment of depressive symptoms with scores of 7 and higher reflecting the presence of at least mild depressive symptomatology (Zimmerman, Martinez, Young, Chelminski, & Dalrymple, 2013). Across studies Cronbach’s alpha scores for the17-item HDRS range from 0.46 to 0.97 (Bagby, Ryder, Schuller, & Marshall, 2004).

Analysis

Prior to analyses, all data were screened by examining frequencies and means to describe the basic characteristics of the PWMCI and family member samples. Paired samples t-tests (for normally distributed subscales) or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests (for nonnormally distributed subscales) were utilized to compare mean differences between pairs of PWMCI and family members along each dimension of illness perception, including emotional distress. We used correlational techniques to determine which of the metacognitive dimensions of illness perception were related to emotional distress in each member of the dyad. Correlations with p values less than .10 were flagged for use in the final modeling process. We chose a less conservative p value to ensure that potential important predictors were not excluded in the modeling process. Additionally, the correlations between partners were examined to provide comprehensive information about the relationships between PWMCI and family member scores.

The Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) framework for distinguishable dyads was used to conduct statistical analyses (Kenny, Kashy & Cook, 2006). Data were arranged in a pairwise structure, with responses of both the PWMCI and family member and the inclusion of a “role” variable to distinguish between the PWMCI and family member responses. The APIM method assumes non-independence of dyadic responses, allowing one to determine how an outcome (in this case, MCI-related emotional distress) is influenced by both members of the dyad. The actor effects occur at the intrapersonal level and refer to the influence of one member of the dyad’s MCI-related metacognitions on that person’s MCI-related emotional distress; that is, the PWMCI’s influence on self or the family member’s influence on self (see Figure 1). The partner effects are intrapersonal and refer to the influence of the other member of the dyad’s metacognitions on the actor’s emotional upset score; that is, the family member’s influence on the PWMCI’s emotional status or the PWMCI’s influence on the family member’s emotional status.

All APIM models were estimated using multilevel modeling with SAS PROC MIXED. Multilevel modeling considers that the members of a dyad have nested scores within the same group. In this analyses, the scores on all variables differed within and between dyads; therefore, these variables were considered “mixed” variables (Kenny et al., 2006). Predictors (metacognitions and age) were grand-mean centered using the mean of the combined data as recommended by Campbell & Kashy (2002), and interactions between the role (PWMCI or family member) and each of the predictors were created.

To test our hypotheses that MCI-related emotional distress among MCI care dyads would be (a) inversely associated with perceived illness coherence, and (b) positively associated with ratings of the seriousness of MCI’s potential consequences, we created a series of models. Each metacognition, including illness coherence and perceived seriousness of MCI’s consequences, was assessed in a separate model to determine if the interaction effects reflecting one’s role in the dyad were significant; all significant interactions were retained for additional model testing. A final model was formed using meta-cognitions that were associated with emotional reaction (p < .10) and significant interactions while controlling for age and relationship. The nested likelihood ratio test was used to select the model that best fit the data. According to Nnadi-Okolo (1990), the subject-to-variable ratio should be 10:1; that is, at least 10 subjects per predictor. Therefore, our sample size of 60 would allow for as many as 6 predictors in each model. All analyses were performed using SAS v. 9.3 and significance level was set to .05 for examination of model effects.

Results

A total of MCI 60 PWMCI/family member dyads participated in the study (Table 1). Forty percent of the PWMCI (n = 24) and nearly three quarters of the family members (n = 44) were female. The vast majority of both the PWMCI (92%; n =55) and family members (92%; n =55) were Caucasian. Forty-eight PWMCI had a focal amnestic deficit and 12 had another neuropsychological testing profile consistent with MCI. Participants had minimal depressive symptoms (mean HDRS = 4.4; SD = 4.36) and the mean MMSE score was 27 (SD = 2.16).

Table 1.

Characteristics of MCI Participants and Care Partners

| Characteristic | MCI participants (n = 60) | Care partners (n = 60) |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years, M ± SD | 71.0±9.4 | 64.2±11.0 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 36 (60.0) | 16 (26.7) |

| Female | 24 (40.0) | 44 (73.3) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 55 (91.7) | 55 (91.7) |

| African American | 5 (8.3) | 5 (8.3) |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| High school or less | 18 (30.0) | 22 (36.7) |

| College or beyond | 42 (70.0) | 38 (68.3) |

| Relation to MCI participant, n (%) | ||

| Spouse | — | 45 (75.0) |

| Adult child | — | 10 (16.7) |

| Other | — | 5 (8.3) |

| Number of months since diagnosis, M ± SD | 4.3±3.6 | — |

| MCI type | 48 (80.0) | — |

| Amnestic | 12 (20.0) | — |

| Nonamnestic | ||

| MMSE score, M ± SD | 27.5±2.2 | — |

| Hamilton DRS score, M ± SD | 4.4±4.4 | — |

Note: PWMCI = persons with mild cognitive impairment.

PWMCI and Family Member MCI Illness Perceptions

Table 2 shows the mean scores of PWMCI and family member ratings of MCI-related illness perceptions. Discordant perceptions were noted on ratings of the controllability and potential seriousness of MCI, with PWMCI perceiving themselves to have more personal control over their MCI symptoms (t = 2.468; p = .017), and family members being more inclined to view MCI as having serious consequences (t = −2.562; p = .013). However, within dyads, there was a significant, positive correlation between viewing MCI as potentially serious (Table 3). Table 3 also reports the correlations between the metacognitive domains and the emotional distress score of the PWMCI and family members. Seriousness was related to both PWMCI (r = .54, p < .001) and family member (r = .51, p < .001) MCI-related emotional distress. Timeline cyclical was also associated with both PWMCI (r = .24, p = .06) and family member (r = .30, p = .02) MCI-related emotional distress. Additionally, family member MCI-related emotional distress was associated with timeline (r = .29, p = .03) and illness coherence (r = −.37, p = .004).

Table 2.

Persons With MCI (PWMCI) and Family Member MCI Illness Perceptions

| Dimension of illness perception (sample item) | Mean/median rating (n = 60 dyads) | Test statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PWMCI | Family | ||

| Timeline chronic (I expect (my loved one) to have these memory or thinking difficulties for the rest of my (his) life.) Six items; maximum score = 30 |

18.66±4.1/19 | 19.46±4.0/20 | Z = −.948, p = .343 |

| Seriousness (My (loved one’s) memory or thinking difficulties are a serious condition.) Six items; maximum score = 30 |

16.46±5.1/16 | 18.61±5.9/18 | t = −2.562, p = .013 |

| Personal control (There is a lot which I (my loved one) can do to control my (her) symptoms.) Six items; maximum score = 30 |

20.60±4.5/21 | 18.75±4.7/19 | t = 2.468, p =.017 |

| Illness coherence (The symptoms of my (loved one’s) condition are puzzling to me.) Five items; maximum score = 25 |

16.25±4.5/17 | 17.48±3.9/19 | Z = −1.733, p =.083 |

| Timeline cyclical (My (loved one’s) symptoms come and go in cycles.) Four items; maximum score = 20 |

9.96±3.5/9 | 10.98±3.8/10 | Z = −1.853, p =.064 |

| Emotional upset (When I think about my (loved one’s) memory or thinking difficulties, I get upset.) Five items; maximum score = 25 |

16.65±4.9/16 | 17.01±4.5/16 | t = −.479, p =.634 |

Note: PWMCI = persons with mild cognitive impairment.

Table 3.

Correlations Between Metacognitions and Emotional Reactions

| Metacognition | Correlation with MCI-related emotional distress | Correlation with family care partner’s metacognition score | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PWMCI | Family Member | PWMCI | |

| Timeline | 0.18 | 0.29* | −0.09 |

| Seriousness | 0.54* | 0.51* | 0.30* |

| Personal control | 0.02 | −0.16 | 0.20 |

| Illness coherence | −0.05 | −0.37* | 0.07 |

| Timeline cyclical | 0.24* | 0.30* | 0.13 |

Note: PWMCI = persons with mild cognitive impairment.

*p < .10

Table 4 reports results of the multilevel models for each of the metacognitive domains. In the model examining seriousness, the PWMCI seriousness score was a significant predictor of PWMCI’s own MCI-related emotional distress. The family member*partner interaction was significant, indicating that family members partnered with PWMCI who report a high seriousness score also report a higher MCI-related emotional distress score. Additionally, the PWMCI*partner interaction was significant in the model examining illness coherence, indicating that PWMCI partnered with family members who report higher illness coherence scores report lower MCI-related emotional distress.

Table 4.

Associations of Metacognitions With Emotional Distress in MCI

| b | se | T | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timeline | ||||

| Person with MCI (PWMCI) actor | 0.09 | 0.33 | 0.29 | .77 |

| Family member actor | −0.01 | 0.34 | −0.06 | .95 |

| PWMCI*partner | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.68 | .50 |

| Family member*partner | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.70 | .48 |

| Seriousness | ||||

| PWMCI actor | 0.81 | 0.23 | 3.47 | <.001** |

| Family member actor | −0.52 | 0.21 | −2.45 | .016 |

| PWMCI*partner | −0.25 | 0.14 | −1.85 | .07 |

| Family member*partner | 0.42 | 0.13 | 3.18 | .002* |

| Personal control | ||||

| PWMCI actor | 0.15 | 0.32 | 0.49 | .62 |

| Family member actor | 0.16 | 0.31 | 0.51 | .61 |

| PWMCI*partner | −0.15 | 0.19 | −0.77 | .45 |

| Family member*partner | −0.13 | 0.19 | −0.69 | .49 |

| Illness coherence | ||||

| PWMCI actor | 0.40 | 0.31 | 1.28 | .20 |

| Family member actor | −0.66 | 0.34 | −1.91 | .06 |

| PWMCI*partner | −0.41 | 0.19 | −2.08 | .04* |

| Family member*partner | 0.35 | 0.20 | 1.70 | .09 |

| Timeline cyclical | ||||

| PWMCI actor | 0.34 | 0.39 | 0.88 | .38 |

| Family member actor | −0.02 | 0.37 | −0.05 | .96 |

| PWMCI*partner | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.02 | .98 |

| Family member*partner | −0.01 | 0.23 | −0.01 | .99 |

Note: Partner effects refer to the other member of the dyad’s score on the designated metacognition measure. PWMCI = persons with mild cognitive impairment.

A final model containing all variables associated with MCI-related emotional distress (see Table 3) as well as the significant interactions of seriousness (family member*partner) and illness coherence (PWMCI*partner) while controlling for age and relationship was then created. Table 5 reports the parameter estimates of all variables in the final model. The family member*partner seriousness interaction was still significant while controlling for all variables in the model (p = .02); however, the PWMCI*partner illness coherence interaction was not significant (p = .07). The PWMCI’s seriousness score remained a significant predictor of their own MCI-related emotional distress (p < .001) while controlling for all variables in the model.

Table 5.

Parameter Estimates of Overall Model

| b | se | T | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| Person with MCI (PWMCI) | −0.04 | 0.04 | −1.34 | .18 |

| Family member | 0.08 | 0.04 | 2.24 | .02 |

| Relationship | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.96 | .34 |

| Timeline | ||||

| Family member | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.81 | .41 |

| Seriousness | ||||

| PWMCI | 0.28 | 0.08 | 3.80 | <.001 |

| Family member | −0.31 | 0.23 | −1.37 | .17 |

| Family Member*role | 0.32 | 0.13 | 2.47 | .02 |

| Illness coherence | ||||

| PWMCI | 0.30 | 0.28 | 1.05 | .29 |

| Family member | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.39 | .70 |

| PWMCI*role | −0.30 | 0.17 | −1.80 | .07 |

| Timeline cyclical | ||||

| PWMCI | 0.15 | 0.11 | 1.43 | .16 |

| Family member | −0.08 | 0.12 | −0.68 | .50 |

Note: PWMCI = persons with mild cognitive impairment.

Discussion and Conclusions

Individuals with MCI are at heightened risk for dementia syndromes (Espinosa et al., 2013) including AD, which is one of the most feared diseases in late life (Anderson, Day, Beard, Reed, & Wu, 2009). As the field of AD research moves toward identifying secondary prevention strategies for dementia, persons with MCI will represent key targets for biomarker testing for AD and ultimately for treatments to slow or stop disease progression. Perceptions of MCI within MCI care dyads are likely to influence decisions to pursue such clinical options. Our study systematically examined MCI-related illness perceptions, including metacognitive and emotional, within both members of the MCI care dyad as well as the dyadic level. In doing so, we have demonstrated that PWMCI and their immediate family members have distinct, yet partially interrelated, cognitive perspectives of and emotional responses to MCI.

Recognizing that, in many cases, both persons with MCI and their family care partners are concurrently coming to terms with the symptoms and diagnosis of the syndrome, we examined the possibility that beliefs and perceptions about MCI that are held by either member of the care dyad may impact MCI-related emotional distress within both members of the dyad Our analysis tested the hypothesis that if one member of the dyad views MCI as only mildly serious, it may nevertheless be emotionally distressing to witness one’s partner experiencing concern about the potential seriousness of MCI-related cognitive changes. Our findings support the presence of such of phenomenon among MCI care dyads, as perceived seriousness of MCI was positively associated with both PWMCI’s own as well as their family member’s MCI-related emotional distress. Our analyses revealed partial support for our related hypothesis that illness coherence, or perceiving oneself to have a clear and cohesive understanding of MCI, was associated with less MCI-related emotional distress. This relationship was supported in our first series of models, yet in our final model, illness coherence was not significantly associated with MCI-related emotional distress in MCI care dyads.

Prior studies of emotional distress in MCI care dyads have been conducted primarily at the individual level, focusing on either the PWMCI, or the family care partner and assessing mood or well being at a general level. Extending this work, this study focused on MCI-specific emotional distress and included analyses at the dyadic level. For both members of the MCI care dyad, median ratings of MCI-related emotional distress were 16 out of a possible 25. Other researchers using the IPQ have interpreted illness-related emotion scores above the scale mid-point to reflect distress. The level of illness-related distress observed in this study is greater than has been observed in other investigations based on Leventhal’s Common Sense model that have used the IPQ-R. Specifically, mean scores on the emotional representation subscale of the IPQ-R have been reported as 14.3 (SD = 5.2) in osteoarthritis (Bijsterbosch et al., 2009), 14.5 (SD = 4.8) in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Fischer et al., 2010), 9.83 (SD = 3.1) in head and neck cancer (Llewellyn, McGurk, & Weinman, 2007), and 12.1 (SD = 3.61) in patients and 12.6 (SD = 3.74) in caregivers of those with diabetes (Searle, Norman, Thompson, Vedhara, 2007). Although unlikely to account for the higher ratings of emotional distress noted in our sample, it should be noted that those studies administered the IPQ-R as a questionnaire, while this study administered the tool using a face-to-face interview.

In general, the finding of a positive association between viewing a disorder as potentially serious and perceiving it as emotionally distressing is consistent with prior research. This relationship was noted in both Covic, Seica, Gusbeth-Tatomir, Gavrilovici, and Goldsmith’ (2004) study of 82 medically stable end-stage renal disease patients on hemodialysis, and in Fischer and colleagues’ (2010) study of 87 patients in a pulmonary rehabilitation setting. While illness-related emotional distress as measured by the IPQ-R has been associated with more general psychological distress (e.g., depression) in samples of persons with a range of chronic disorders (e.g., Cameron et al., 2005), it is important to note that the current sample was not depressed. Rather, the emotional distress measured in this study was specific to one’s feelings about MCI. Given recent reports that an individual’s perceptions about the experience of cognitive impairment can be altered by underlying depressive symptoms (Schulz et al., 2010), the absence of clinical depression in our sample strengthens this study.

On a related note, it is also worth discussing the possibility that being less inclined to view MCI as having serious consequences may yield less emotional distress. Relative to family members, PWMCI in our sample minimized the potential seriousness of the syndrome. This finding regarding the potential seriousness of MCI may be considered within the context of prior work examining individuals’ views of MCI in relation to normal aging. For example, Lin and colleagues (2012) interviewed 30 PWMCI and found that the syndrome was generally viewed as being chronic, predictable, and caused by normal aging. While one may question the extent to which participants in that study were educated about their diagnosis, another small study showed that, despite undergoing a formal diagnostic disclosure, some individuals who had been recently diagnosed with MCI attributed their cognitive symptoms to normal aging (Lingler et al., 2006). This pattern of results in MCI is consistent with several other reports that older adults with and without cognitive impairment view cognitive decline to be an expected consequence of aging (Clare, Goater, & Woods, 2006; Wu, Goins, Laditka, Ignatenko & Goedereis, 2009).

Given the wide variability in emotional well-being and related perceptions that have been documented among PWMCI and their family members, further studies are needed to understand the correlates and patterns of emotional responses to the syndrome, and to develop educational and supportive interventions that are responsive to the nuances of MCI perceptions within affected dyads and families. There seems to be a particular need for dyadic level interventions that find middle ground in terms of conveying the risks of MCI as distinct from normal aging without unduly upsetting affected individuals. Interventions encouraging MCI care dyads to explore their shared and divergent perceptions of the syndrome are also needed, as are outcome assessments that capture dyadic well-being.

Limitations

Our sample had little racial and ethnic diversity. This is major limitation of our study as culture is well documented to impact health beliefs (Becker, Gates, & Newsom, 2004). The cross-sectional design of this study poses another significant limitation, given that illness perceptions for chronic disorders are shaped over time (Tasmoc, Hogas, & Covic, 2013). Our cross-sectional design also precluded us from determining the direction of any relationships noted among the dimensions of illness perception. Indeed, emotional distress could be influencing MCI related metacognitions. Our sample size was also a limitation of the study, as a larger sample would allow for the inclusion of more potential predictors in the modeling process. We collected limited information from family care partners, constraining our ability to examine the potential influence of factors like care partners’ degree of engagement in caregiving activities. Finally, it should be noted that this sample consisted of individuals who sought out evaluations of their cognitive impairment and may have been more inclined to find such impairment distressing than would others experiencing MCI in the general population.

Conclusions

Overall, our findings suggest that clinicians who are counseling PWMCI and family members affected by MCI need to take into consideration an individual’s set of beliefs concerning MCI and their (or their family member’s) prognosis and emotional state. Our models showed that MCI-related emotional distress, in both PWMCI and family members, is linked squarely to the PWMCI’s perception of the potential seriousness of MCI’s consequences. This raises the possibility that interventions aimed toward supporting PWMCI may be beneficial for dyadic well-being. Supportive and educational interventions targeting both members of the care dyad should be evaluated for their potential to bring PWMCI and their family members to an improved understanding of each others’ perspectives and emotions related the syndrome. A shared understanding of what MCI means, and how family members feel about the syndrome, is likely to be an important underpinning of effective coping among MCI care dyads.

Funding

This research was supported by an Alzheimer’s Association New Investigator Research Grant (PI: Lingler) and National Institutes of Health P50 AG05133 (PI: Lopez).

References

- Anderson L. A., Day C. L., Beard R. L., Reed P. S., Wu B. (2009). The public’s perceptions about cognitive health and Alzheimer’s disease among the U.S. population: a national review. The Gerontologist, 49, S3–S11. doi:10.1093/geront/gnp088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagby R. M. Ryder A. G. Schuller D. R., & Marshall M. B (2004). Reviews and overviews. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: Has the gold standard become a lead weight? American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 2163–2177. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard R. L., Neary T. M. (2013). Making sense of nonsense: experiences of mild cognitive impairment. Sociology of Health & Illness, 35, 130–146. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2012.01481.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker G., Gates R. J., Newsom E. (2004). Self-care among chronically ill African Americans: culture, health disparities, and health insurance status. American Journal of Public Health, 94, 2066–2073. doi:10.2105/AJPH.94.12.2066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijsterbosch J. Scharloo M. Visser A. W. Watt I. Meulenbelt I. Huizinga T. W. J.…Kloppenburg M (2009). Illness perceptions in patients with osteoarthritis: change over time and association with disability. Arthritis Care & Research, 61, 1054–1061. doi:10.1002/art.24674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blieszner R. Roberto K. A. Wilcox K. L. Barham E. J., & Winston B. L (2007). Dimensions of ambiguous loss in couples coping with mild cognitive impairment. Family Relations, 56, 196–209. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00452.x [Google Scholar]

- Blieszner R., Roberto K. A. (2010). Care partner responses to the onset of mild cognitive impairment. The Gerontologist, 50, 11–22. doi:10.1093/geront/gnp068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron L. D. Booth R. J. Schlatter M. Ziginskas D. Harman J. E., & Benson S. R. C (2005). Cognitive and Affective Determinants of Decisions to Attend a Group Psychosocial Support Program for Women With Breast Cancer Psychosomatic Medicine, 67, 584–589. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000170834.54970.f5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L., Kashy D. A. (2002). Estimating actor, partner, and interaction effects for dyadic data using PROC MIXED and HLM: A user-friendly guide. Personal Relationships, 9, 327–342. doi:10.1111/1475-6811.00023 [Google Scholar]

- Clare L., Goater T., Woods B. (2006). Illness representations in early-stage dementia: a preliminary investigation. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21, 761–767. doi:10.1002/gps.1558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook W. L., & Kenny D. A (2005). The actor-partner interdependence model: A model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29, 101–109. doi:10.1080/01650250444000405 [Google Scholar]

- Covic A. Seica A. Gusbeth-Tatomir P. Gavrilovici O., & Goldsmith D. J (2004). Illness representations and quality of life scores in haemodialysis patients. Nephrology, Dialysis & Transplantation,19, 2078–2083. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfh254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa A. Alegret M. Valero S. Vinyes-Junqué G. Hernández I. Mauleón A.,…Boada M (2013). A longitudinal follow-up of 550 mild cognitive impairment patients: evidence for large conversion to dementia rates and detection of major risk factors involved. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 34, 769–780. doi:10.3233/JAD-122002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer M. Scharloo M. Abbink J. van ‘t Hul A. van Ranst D. Rudolphus A.,…Kaptein A. A (2010). The dynamics of illness perceptions: testing assumptions of Leventhal’s common-sense model in a pulmonary rehabilitation setting. British Journal of Health Psychology, 15(Pt 4), 887–903. doi:10.1348/135910710X492693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein M. F., Folstein S. E., McHugh P. R. (1975). “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12, 189–198. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank L., Lloyd A., Flynn J. A., Kleinman L., Matza L. S., Marqolis M. K.,…, Bullock R. (2006). Impact of cognitive impairment on mild dementia patients and mild cognitive impairment patients and their informants. International Psychogeriatrics, 18, 151–162. doi:10.1017/S1041610205002450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garand L., Dew M. A., Eazor L. R., DeKosky S. T., Reynolds C. F. (2005). Caregiving burden and psychiatric morbidity in spouses of persons with mild cognitive impairment. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 20, 512–522. doi:10.1002/gps.1318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. (1960). A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 23, 56–62. doi:10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny D. A. Kashy D. A., & Cook W. L (2006). Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford; [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H. Brissette I., & Leventhal E. A (2003). The common-sense model of self regulation of health and illness. In Cameron L.D., Leventhal H. (Eds.), The self-regulation of health and illness behaviour (pp. 42–65). London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lingler J. H., Nightingale M. C., Erlen J. A., Kane A., Reynolds C. F., Schulz R., DeKosky S. T. (2006). Making sense of mild cognitive impairment: a qualitative exploration of the patient’s experience. The Gerontologist, 46, 791–800. doi:10.1093/geront/46.6.791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llewellyn C. D., McGurk M., Weinman J. (2007). Illness and treatment beliefs in head and neck cancer: is Leventhal’s common sense model a useful framework for determining changes in outcomes over time? Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 63, 17–26. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez O. L. Becker J. T. Klunk W. Saxton J. Hamilton R. L. Kaufer D. I.…DeKosky S. T (2000). Research evaluation and diagnosis of probable Alzheimer’s disease over the last two decades: I. Neurology, 55, 1854–1862. doi:10.1212/WNL.55.12.1854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez O. L. Jagust W. J. DeKosky S. T. Becker J. T. Fitzpatrick A. Duhlberg C.,…Kuller L. H (2003). Prevalence and classification of mild cognitive impairment in the Cardiovascular Health Cognition Study: Part 1. Archives of Neurology, 60, 1385–1389. doi:10.1001/archneur.60.10.1385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y. F., Haase J. E. (2009). Experience and perspectives of caregivers of spouse with mild cognitive impairment. Current Alzheimer Research, 6, 384–391. doi:10.2174/156720509788929309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIlvane J. M., Popa M. A., Robinson B., Houseweart K., Haley W. E. (2008). Perceptions of Illness, coping, and well-being in persons with mild cognitive impairment and their care partners. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 22, 284–292. doi:10.1097/WAD.0b013e318169d714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell A. J., & Shiri-Feshki M (2009). Rate of progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia: Meta-analysis of 41 robust inception cohort studies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 119, 252–265. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01326.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss-Morris R. Weinman J. Petrie K. J. Horne R. Cameron L.D., & Buick D (2002). The Revised Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ-R). Psychology and Health, 17, 1–16. doi:10.1080/08870440290001494 [Google Scholar]

- Nnadi-Okolo E. (1990). Health research design and methodology. Boca Raton: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen R. C., Doody R., Kurz A., Mohs R. C., Morris J. C., Rabins P. V., et al. (2001). Current concepts in mild cognitive impairment. Archives of Neurology, 58, 1985–1992. doi:10.1001/archneur.58.12.1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberto K. A., Blieszner R., McCann B. R., McPherson M. C. (2011). Family triad perceptions of mild cognitive impairment. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66, 756–768. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbr107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts J. L., Clare L. (2013). Meta-representational awareness in mild cognitive impairment: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Aging & Mental Health, 17, 300–309. doi:10.1080/13607863.2012.732033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samsi K., Abley C., Campbell S., Keady J., Manthorpe J., Robinson L.,…, Bond J. (2014). Negotiating a labyrinth: experiences of assessment and diagnostic journey in cognitive impairment and dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29, 58–67. doi:10.1002/gps.3969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R. Monin J. Czaja S. J. Lingler J. Beach S. Martire L. M.…Cook T. B (2010). Measuring the experience and perception of suffering. The Gerontologist, 50, 774–784. doi:10.1093/geront/gnq033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searle A., Norman P., Thompson R., Vedhara K. (2007). Illness representations among patients with type 2 diabetes and their partners: relationships with self-management behaviors. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 63, 175–184. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeher K. M. Low L. Reppermund S., & Brodaty H (2013). Predictors and outcomes for caregivers of people with mild cognitive impairment: a systematic literature review. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 9, 346–355. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2012.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeher K. M. Low L. Reppermund S. Slavin M. Draper B. Kang K.,…Brodaty H (2014). Correlates of psychological distress in study partners of older people with and without mild cognitive impairment (MCI) – the Sydney Memory and Ageing Study. Aging & Mental Health, 18, 694–705. doi:10.1080/13607863. 2013.875123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springate B.A., Tremont G. (2014). Caregiver burden and depression in mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 32, 765–775. doi:10.1177/0733464811433486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasmoc A. Hogas S., & Covic A (2013). A longitudinal study on illness perceptions in hemodialysis patients: changes over time. Archives of Medical Science: AMS, 9, 831–836. doi:10.5114/aoms.2013.38678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinman J. A. Petrie K. J. Moss-Morris R., & Horne R (1996). The Illness Perception Questionnaire: A new method for assessing the cognitive representation of illness. Psychology and Health, 11, 114–129. doi:10.1080/08870449608400270 [Google Scholar]

- Wu B., Goins R. T., Laditka J. N., Ignatenko V., Goedereis E. (2009). Gender differences in views about cognitive health and healthy lifestyle behaviors among rural older adults. The Gerontologist, 49, S72–S78. doi:10.1093/geront/gnp077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M. Martinez J. H. Young D. Chelminski I., & Dalrymple K (2013). Severity classification on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150, 384–388. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]