Abstract

Purpose of the Study:

Using retrospective global reports, studies have found that middle-aged adults in the United States provide intermittent support to their aging parents and more frequent support to grown children. To date, studies have not examined support middle-aged adults provide to different generations on a daily basis. Daily support may include mundane everyday exchanges that may (or may not) affect well-being.

Design and Methods:

Middle-aged adults (N = 191, mean age 55.93) completed a general interview regarding family ties, followed by interviews each day for 7 days (N = 1,261 days). Daily interviews assessed support (e.g., advice, emotional, practical help) participants provided each grown child (n = 454) and aging parent (n = 253). Participants also reported daily mood.

Results:

Most participants provided emotional support (80%), advice (87%), and practical help (69%) to a grown child and also provided emotional support (61%) and advice (61%) or practical help (43%) to a parent that week. Multilevel models confirmed generational differences; grown children were more likely to receive everyday support than parents. Providing support to grown children was associated with positive mood, whereas providing support to parents was associated with more negative mood.

Implications:

Daily intergenerational support was more common than studies using global reports of support have found. Some daily support may be fleeting and not stand out in memory. The findings were consistent with the intergenerational stake hypothesis, which suggests middle-aged adults are more invested in their grown children than in their parents. Nonetheless, middle-aged adults were highly involved with aging parents.

Keywords: Intergenerational ties, Diary study, Aging parents, Grown children, Daily support

Middle-aged adults provide frequent support to generations above and below. Over the past decade, support to grown children has increased considerably; middle-aged adults provide frequent and intense support to adult offspring (Arnett & Schwab, 2012; Bucx, van Wel, & Knijn, 2012; Fingerman et al., 2012c). They also provide intermittent support for aging parents in need (Fingerman et al., 2011; Grundy & Henretta, 2006). Data in past studies were derived from global retrospective reports, however, and everyday life may include trivial behaviors that people do not report. Although intergenerational support may occur frequently, we do not know how often and what types of support middle-aged adults provide to parents and grown children on a daily basis.

Daily diary methodologies assess experiences proximate to when events happen and may capture mundane support not recalled in retrospective assessments addressing lengthier time periods (Reis, 2012). We considered three types of support that may occur frequently between generations: emotional support, advice, and practical help. Financial support plays a key role in intergenerational ties as well but typically occurs periodically (Johnson, 2013; Swartz, 2009). We were interested in how middle-aged adults balance support to parents and multiple offspring on an everyday basis, as well as implications of providing support.

Which Generation Receives Everyday Support?

Most prior studies have examined support to one family member, a parent or a grown child (e.g., Martini, Grusec, & Bernardini, 2003; Silverstein, Gans, & Yang, 2006). Yet, many middle-aged adults experience demands from multiple directions and often pivot between parents and grown children (Fingerman et al., 2011; Grundy & Henretta, 2006).

In juggling support to family members, middle-aged adults typically support grown children more than parents. According to the developmental stake hypothesis, parents have a greater investment in the younger generation as a legacy of their own future (Giarrusso, Feng, & Bengtson, 2005). The few studies examining support to both generations have found middle-aged adults give more to offspring than to parents (Fingerman et al., 2011; Grundy & Henretta, 2006). Based on retrospective reports, middle-aged parents may offer support to grown children several times a week or everyday (Fingerman, Cheng, Birditt, & Zarit, 2012a).

This is not to say middle-aged adults neglect their parents. Over a fifth of adults serve as caregivers for an aging parent and these caregivers may provide more support to parents than to grown children (Grundy & Henretta, 2006). Moreover, middle-aged adults may help healthy parents in everyday life, giving emotional support and assisting with minor hassles not assessed elsewhere. A key benefit of daily assessments is identifying support that is not a “big deal,” yet requires time and involvement.

In sum, in examining everyday support, we expected middle-aged adults to support parents and grown children throughout the week but to provide more support on average to grown children than to parents.

Why Do Middle-Aged Adults Provide Daily Support to Family Members?

We considered reasons why middle-aged adults may offer daily support to particular family members including: (a) their needs, (b) emotional rewards of providing support, and (c) competition for help. As such, we applied contingency theory (Eggebeen & Davey, 1998; Fingerman et al., 2011), affectional solidarity theory (Sechrist, Suitor, Howard, & Pillemer, 2014), and the family resource model (Fingerman, Miller, Birditt, & Zarit, 2009; Grundy & Henretta, 2006) to understand who receives help from middle-aged adults each day.

Family Member Needs

According to contingency theory, needs elicit support. Eggebeen and Davey (1998) laid important groundwork for this theory with regard to intergenerational exchanges by showing that middle-aged adults increase support when parents’ health declines in late life. Similarly, middle-aged adults may respond to a plethora of family member needs on a daily basis. In the 21st century, young adults often prolong their education and delay marriage (Furstenberg, 2010) and parents may help with everyday needs. Young adulthood also is characterized by instability; grown children may suffer problems such as unemployment or divorce, which elicit parental support (Furstenberg, 2010).

Although older parents also have everyday needs, societal norms in Western countries favor a flow of support from parents to grown children rather than the reverse (Fingerman et al., 2011; Grundy & Henretta, 2006; Kohli, 2005). Thus, aging parents turn to a spouse, friends, or other parties for help. Yet, when aging parents are disabled, widowed, or suffer crises, contingency theory suggests middle-aged children offer support (Ha, Carr, Utz, & Ness, 2006).

In sum, we expected middle-aged adults to provide everyday support based on family members’ needs including: student status, being unmarried, suffering life problems (e.g., divorce, job loss, victim of crime), or disability.

Positive Relationship Quality and Rewards

In addition to responding to needs, solidarity theory suggests support occurs in the context of relationships characterized by greater affection (Fingerman et al., 2011; Grundy & Henretta, 2006). Indeed, middle-aged adults are more likely to help aging parents when they have better quality relationships (Schwarz, Trommsdorff, Albert, & Mayer, 2005) and the same is true for offspring. Because middle-aged adults typically experience greater affection for their children than their aging parents (Birditt, 2014), they may be more likely to support grown children on a daily basis.

Similarly, people offer social partners more support when they find it rewarding to help (Dovidio, Piliavin, Schroeder, & Penner, 2006). Of course, people may find it rewarding to help individuals with whom they get along better. Nonetheless, rewards of helping reflect cultural and personal values as well. Thus, we expected participants to offer more support when they felt more affection toward a family member or found it more rewarding to help a family member.

Competition for Support

We also considered family context. Resource depletion theory posits that during childhood, family size limits parental resources to each child (Strohschein, Gauthier, Campbell, & Kleparchuk, 2008). A larger family size diminishes the amount of parental support each grown child receives (Fingerman et al., 2009).

Moreover, support to needy family members may influence support to less needy family members. Prior research finds that parents with more than one child give more support to the child with greater needs (Fingerman et al., 2009) and support to an aging parent is associated with less support to grown children (Fingerman et al., 2011; Grundy & Henretta, 2006). In this study, we asked whether middle-aged adults balance support on a daily basis such that on days when they support one family member, other family members receive diminished support.

By contrast, daily support to one family member may spread to other family members. For example, a grown daughter who drives her father to a doctor’s appointment may offer her mother emotional support in passing. A middle-aged adult may offer collective advice to multiple grown children. We examined whether support to each child or parent was associated with support to other family members each day. Based on resource depletion theory and studies showing support to one generation associated with diminished support to others, we expected family members to receive less support on days when another family member received support, but we considered the alternative hypothesis regarding collective support.

What Are the Implications of Giving Support?

The implications of providing everyday support are unclear. Caregiving for aging parents saps energy (Aneshensel, Pearlin, Mullan, Zarit, & Whitlatch, 1995), and sometimes helping a healthy parent can be taxing. Support to grown children may be demanding as well, particularly if a grown child is experiencing life problems (Fingerman et al., 2012a; Seltzer et al., 2009).

A small literature suggests that giving support can be beneficial. For example, Byers, Levy, Allore, Bruce, and Kasl (2008) found that parents reported fewer depressive symptoms when their grown children depended on them for practical or emotional support perhaps due to competence derived from such involvement. Some caregivers also report that helping parents is emotionally rewarding (Goodman, Steiner, & Zarit, 1997). We assessed both positive and negative mood each day.

The Current Study and Other Factors Associated With Daily Support

We considered other factors associated with support: gender, age, race, health, socioeconomic status (SES), and distance between the parties. We controlled for gender because mother and daughter linkages usually are the most support-laden (Suitor, Pillemer, & Sechrist, 2006). Adults in their 40s are likely to have younger offspring who require more support (Hartnett, Furstenberg, Birditt, & Fingerman, 2013). By contrast, adults in their late 50s and 60s are more likely to have aging parents who require care (Grundy & Henretta, 2006). African Americans show greater stress in reaction to family problems and typically face more demands than European American adults (Cichy, Stawski, & Almeida, 2012). Higher SES parents in better health provide more support to grown children (Grundy, 2005). Finally, distance may constrain the ability to give practical support.

Hypotheses addressed the following research questions. Generational differences: Consistent with Western values for support (Kohli, 2005), we expected middle-aged adults to provide daily support more often to grown children than to parents. Reasons underlying support: We expected needs to elicit daily support. Offspring’s daily needs (e.g., being unmarried, having small children, student status) may help explain generational differences in daily support. When a parent is disabled or suffers life problems, however, middle-aged adults may support the parent. Moreover, consistent with the generational stake, middle-aged adults’ greater affection and rewards of helping grown children may account for more frequent daily support. Regarding family context, we expected competition for support from other children or aging parents to be associated with lessened support to another family member. Daily mood: Reflecting generativity concerns, we expected parents to report better mood on days when they offered grown children emotional support or advice. Providing support to parents may be mixed.

Methods

Participants were middle-aged adults from the Family Exchange Study Wave 2 conducted in 2013. The sample was recruited from the Philadelphia Metropolitan Statistical Area (PMSA) and participated in Wave 1 in 2008. Initial criteria required middle-aged adults to have at least one living parent and one child over age 18. In Wave 2, following completion of a 1-hr main survey, a random selection of participants was invited to complete a diary study consisting of brief telephone interviews for seven evenings. Of those invited, 87% (n = 270) accepted the invitation and 248 participants completed daily interviews before the study was closed.

We limited the current study to diary study participants with at least one living parent (i.e., mother or father) and a grown child (n = 191). Of the diary participants, 56 did not have a living parent and 1 did not have a living grown child. The sample was generally representative of the population of the Philadelphia PMSA (US Census Bureau, 2012; See Table 1).

Table 1.

Background Information for Middle-Aged Participants and Their Grown Offspring and Parents

| Participant (N = 191) | Family member (N = 707) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Offspring (n = 454) | Parent (n = 253) | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Descriptive statistics | ||||||

| Age | 55.93 | 4.87 | 28.39 | 6.64 | 81.53 | 5.99 |

| Years of education | 14.59 | 2.01 | 14.55 | 1.94 | 12.33 | 2.74 |

| Rating of healtha | 3.31 | 0.96 | 4.20 | 0.97 | 2.67 | 1.02 |

| Incomeb | 6.55 | 2.73 | — | — | — | — |

| Number of grown children (18+) | 2.59 | 1.33 | — | — | — | — |

| Number of parents | 1.32 | 0.47 | — | — | — | — |

| Distance from participant (miles) | — | — | 208.10 | 587.14 | 211.57 | 481.01 |

| Number of life problems (seven items) | 1.13 | 1.20 | 0.88 | 1.07 | 1.40 | 1.07 |

| Relationship qualityc | — | — | 3.90 | 0.93 | 3.98 | 0.96 |

| Rewards of helping family memberd | — | — | 4.12 | 0.98 | 4.20 | 1.03 |

| Proportions | ||||||

| Male | .45 | .48 | .36 | |||

| Married or remarried | .73 | .30 | .42 | |||

| Racial/ethnic minoritye | .29 | — | — | |||

| Coresiding with participant | — | .21 | .08 | |||

| Disability | — | .06 | .57 | |||

| Has children under age 18 | .16 | .36 | .00 | |||

| Work status | ||||||

| Employed full- or part-time | .71 | .72 | .05 | |||

| Homemaker | .01 | .04 | .05 | |||

| Student | .00 | .11 | .00 | |||

| Retired or other | .28 | .13 | .90 | |||

a1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, 5 = excellent.

b1 = less than $10,000, 2 = $10,001–$25,000, 3 = $25,001–$40,000, 4 = $40,001–$50,000, 5 = $50,000–$60,000, 6 = $60,001–$75,000, 7 = $75,001–$100,000, 8 = $100,001–$125,000, 9 = $125,001–$150,000, 10 = $150,001–$200,000, 11 = $200,001–$250,000, 12 = $250,001 or more.

cMean of two items rated 1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = somewhat, 4 = quite a bit, 5 = a great deal.

d1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = somewhat, 4 = quite a bit, 5 = a great deal.

e0 = non-Hispanic white, 1 = racial/ethnic minority.

We compared the study sample (n = 191) with the remaining sample in the Family Exchanges Study 2. This sample had more years of education than participants not included (t = 2.10, p < .05; 14.59 years this sample and 14.20 years remaining sample) and more living parents (t = 9.84, p < .001; 1.32 this sample and 0.81 for remaining sample). The sample also had poorer relationship quality with grown children (t = −2.79, p < .01; M = 3.90 this sample and M = 4.05 remaining sample) and was more likely to reside with parents (χ2 = 7.83, p < .01; .08 this sample and .03 remaining sample). The samples did not differ on age, income, health, or race; Supplementary Table 1).

Measures From Main Interview

Participants completed a 1-hr telephone or web-based survey. Participants provided detailed information about their living parents (n = 253) and up to four grown children (n = 454; Table 1). Parents who had more than four grown children (n = 13), reported on: (a) the child they helped most often, (b) the child they helped least often, (c) a random additional child, and (d) youngest child over age 18 not yet discussed.

Background Characteristics

Participants provided background characteristics (e.g., age, education, income, work, and marital status). Participants rated their health from 1 = poor to 5 = excellent (Idler & Kasl, 1991).

Characteristics of Parents and Grown Children

Participants provided background characteristics (e.g., age, gender, marital status), coresidence, and geographic distance for each living parent and grown child. Due to skew, we used the log transformation of distance in analyses.

Family Members’ Needs

Participants indicated parental status (i.e., 1 = had children of his/her own) and student status (1 = student, 0 = not student) for each grown child.

We generated a variable indicating whether each family member suffered a disability (1 = has a functional disability, 0 = no functional disability) based on two separate measurements. Middle-aged adults indicated whether parents had difficulty with personal or daily care, transportation, and finances (Bassett & Folstein, 1991); 144 parents (out of 253 parents, 57%) had such a disability. Participants also indicated whether each grown child suffered a developmental or physical disability; 25 grown children (6%) did so.

We asked whether each parent or child had experienced seven life problems (e.g., financial difficulties, victim of crime, divorce) in the prior 2 years and used the total score (Birditt, Fingerman, & Zarit, 2010; Greenfield & Marks, 2006).

Relationship Quality and Rewards

Participants rated two items regarding positive affection for each parent and grown child, how much the other party: (a) makes them feel loved and cared for and (b) understands them from 1 = not at all to 5 = a great deal (α = .77 for parents and α = .76 for offspring; Birditt et al., 2010; Umberson, 1992).

Participants rated how rewarding they find it to help each parent and each grown child, from 1 = not at all to 5 = a great deal.

Competition for Support

We used the number of children and number of living parents (i.e., family size) as potential competition for support.

Measures From the Diary Survey

Daily telephone surveys obtained information regarding each family member each day. First, we asked whether the participant had contact with any child, followed by which child. Follow-up questions focused on support exchanges on days when contact occurred. Contact included in-person, telephone, and electronic media. We applied a similar approach regarding parents.

Support

Participants reported daily: practical help, advice, and emotional support for each parent and each child. We drew on the social support literature to define (Vaux, 1988): (a) practical help, fixing something around the house, running an errand, or providing a ride; (b) advice, providing information or suggestions about things they could do or helping with a decision; and (c) emotional support, listening to concerns or being available when the other is upset.

Daily Competition for Support

We generated metrics of competition for support each day. We indicated whether the participant assisted another parent or grown child that day (1 = helped a parent or child, 0 = did not help a parent or child) other than the parent or child in question. For each grown child, we indicated whether the participant assisted a different child (1 = helped a different child that day, 0 = did not help other child that day). For parents, we indicated whether the participant helped the other parent. Finally, we considered whether the participant assisted any other people that day (e.g., spouse, sibling, friend).

Daily Mood

Each day, participants rated six positive emotions (e.g., happy, determined, calm; α = .68) and nine negative emotions (e.g., distressed, lonely, nervous; α = .89) drawn from assessments of daily emotions (Birditt, 2014; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) from 1 = none of the day to 5 = all of the day.

Analytic Procedure

We examined descriptive information for each type of support. Then, we considered generational differences (1 = parent, 0 = offspring) in support each day. We used three-level multilevel models (MLMs) for dichotomous outcomes (1 = gave support that day, 0 = no support given that day) using the Glimmix function in SAS. The lowest level was each family member (e.g., parent or grown child) and generation was the level-one predictor. Most participants had one parent but multiple children; MLM accounts for unequal numbers of parents and children within families. The next level was day (i.e., each day participants could provide support to parents and offspring); participants completed up to 7 days. The final level was participant. Support to parent or child was nested within day, nested within participant. We estimated three models, one for each support outcome (i.e., emotional support, advice, practical help).

Participant control variables included: gender (1 = man, 0 = woman), age, years of education, self-rated health, and minority status. We controlled for family member gender and distance from participant in miles (log transformation). Family members’ ages and minority status were correlated with participants’ and thus not included in models.

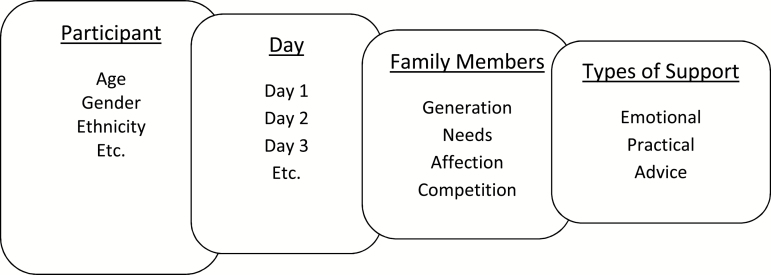

We also examined variables reflecting: (a) needs (e.g., student status, disability), (b) affection and rewards of helping, and (c) competition for support (e.g., number of children or parents, support to others that day). We estimated models separately for each type of support (Figure 1 illustrates nested structure of the data).

Figure 1.

Nested structure of the data.

Finally, we examined positive and negative mood as continuous variables using MLM procedures with two levels: days nested within participants. Predictors were providing each type of support to each generation on that day. That is, we generated six aggregate variables for each day: provided any parent with practical support that day, provided any offspring with practical support that day, provided any parent with advice that day, and so forth. We examined: (a) same day provision of support predicting same day mood and (b) lagged models in which the prior day’s provision of support predicts the next day’s mood to examine lingering effects of events (Cichy, Stawski, & Almeida, 2014; Reis, 2012).

Results

On average, participants had contact with a grown child on 5.17 days (SD = 2.01) and an aging parent on 3.18 days (SD = 2.36). Most participants provided emotional support (80%) or advice (87%) to a grown child at least 1 day that week, and over two thirds provided practical help. Many participants (61%) provided emotional support and advice to a parent, and nearly half (43%) provided practical help (Table 2). Although support was relatively frequent (e.g., participants provided emotional support to a grown child on 42% of study days), it was not as frequent as contact. Apparently, contact occurs for reasons other than support.

Table 2.

Proportion of Participants Reporting Each Type of Support With Children and Parents During the Study Week

| Proportion of participants providing support at least once that week | Proportion of days that week participant provided support | |

|---|---|---|

| Support provided to offspring | ||

| Emotional support | .80 | .42 |

| Advice | .87 | .47 |

| Practical help | .69 | .31 |

| Support provided to parents | ||

| Emotional support | .61 | .25 |

| Advice | .61 | .22 |

| Practical help | .43 | .17 |

Note: Participant N = 191; Day N = 1,261.

Generational Differences and Variables Associated With Daily Support

We estimated logistic MLMs examining likelihood of middle-aged adults providing each type of support each day to each generation. Participants were more likely to provide support to grown children than to parents, controlling for participant and family member characteristics (Table 3). The average child was 1.3 times as likely to receive emotional support, 1.82 as likely to receive advice, and 1.26 times as likely to receive practical help as the average parent each day. These analyses pertain to support to each child, not support to any child, and thus, partially account for the fact that most participants have more children than parents.

Table 3.

Logistic Multilevel Models for Each Type of Daily Support Participants Provide to Each Generation of Family Members

| Emotional support | Advice | Practical help | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | p value | Odds ratio | B | SE | p value | Odds ratio | B | SE | p value | Odds ratio | |

| Fixed effects | ||||||||||||

| Intercept | −2.67 | 1.26 | .04 | −0.71 | 1.05 | .50 | −1.14 | 1.20 | .34 | |||

| Generationa | −0.25 | 0.09 | <.01 | 0.78 | −0.60 | 0.09 | <.001 | 0.55 | −0.23 | 0.11 | .03 | 0.80 |

| Control variables | ||||||||||||

| Participant: Genderb | −0.10 | 0.19 | .61 | 0.91 | −0.19 | 0.16 | .24 | 0.83 | −0.27 | 0.18 | .14 | 0.77 |

| Participant: Age | 0.00 | 0.02 | .93 | 1.00 | −0.02 | 0.02 | .18 | 0.98 | −0.02 | 0.02 | .31 | 0.98 |

| Participant: Years of education | 0.11 | 0.05 | .02 | 1.12 | 0.10 | 0.04 | .02 | 1.11 | 0.10 | 0.05 | .03 | 1.11 |

| Participant: Healthc | 0.13 | 0.10 | .23 | 1.13 | 0.06 | 0.09 | .50 | 1.06 | 0.08 | 0.10 | .40 | 1.09 |

| Participant: Minority statusd | −0.07 | 0.22 | .74 | 0.93 | −0.05 | 0.18 | .80 | 0.96 | −0.04 | 0.20 | .86 | 0.97 |

| Family member: Genderb | −0.51 | 0.09 | <.001 | 0.60 | −0.36 | 0.09 | <.001 | 0.70 | −0.56 | 0.11 | <.001 | 0.57 |

| Family member: Distancee | −0.19 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.83 | −0.20 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.82 | −0.48 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.62 |

| Random effects | ||||||||||||

| Intercept VAR (Level 2: Day) | 0.15 | 0.08 | .06 | 0.16 | 0.07 | .03 | 0.08 | 0.09 | .42 | |||

| Intercept VAR (Level 3: Participant) | 1.21 | 0.18 | <.001 | 0.78 | 0.12 | <.001 | 0.90 | 0.15 | <.001 | |||

| −2 (pseudo) log-likelihood | 21263.73 | 20846.91 | 23250.28 | |||||||||

Note: Participant N = 191; Day N = 1,261 (up to 7 days per participant); Family member N = 707 (offspring n = 454; parent n = 253). VAR = variance.

a0 = offspring generation, 1 = parent generation.

b0 = female, 1 = male.

c1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, 5 = excellent.

d0 = non-Hispanic white, 1 = racial/ethnic minority.

eDistance in miles using a log transformation.

Needs

We asked whether family members’ needs explained daily support. As seen in Table 4, regardless of generation, life problems evoked daily advice and emotional support; for each additional life problem, family members were 1.19 times as likely to receive emotional support and 1.10 times as likely to receive advice compared with family members with fewer problems. Disability elicited practical help; disabled family members were 1.74 times as likely to receive practical help. Offspring who were parents of young children themselves were less likely to receive advice; nonparents were 1.32 times as likely to receive advice as parents of small children. Family members who were not married were more likely to receive all types of support, odds ratio of 1.30 emotional support, 1.31 advice, and 1.33 practical help.

Table 4.

Logistic Multilevel Models for Each Type of Daily Support Participants Provide by Family Member Needs

| Emotional support | Advice | Practical help | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | p value | Odds ratio | B | SE | p value | Odds ratio | B | SE | p value | Odds ratio | |

| Fixed effects | ||||||||||||

| Intercept | −3.63 | 1.24 | <.01 | −1.49 | 1.05 | .16 | −1.78 | 1.21 | .14 | |||

| Generationa | −0.41 | 0.14 | <.01 | 0.67 | −0.81 | 0.13 | <.001 | 0.45 | −0.44 | 0.17 | <.01 | 0.65 |

| Unmarried | 0.26 | 0.12 | .03 | 1.30 | 0.27 | 0.11 | .02 | 1.31 | 0.29 | 0.14 | .04 | 1.33 |

| Student | 0.24 | 0.17 | .14 | 1.28 | 0.17 | 0.16 | .27 | 1.19 | 0.36 | 0.19 | .05 | 1.44 |

| Disability | 0.13 | 0.14 | .33 | 1.14 | 0.19 | 0.13 | .15 | 1.21 | 0.55 | 0.16 | <.001 | 1.74 |

| Offspring has children under age 18 | −0.16 | 0.15 | .28 | 0.85 | −0.28 | 0.14 | .04 | 0.76 | 0.16 | 0.17 | .34 | 1.18 |

| Number of life problems | 0.16 | 0.05 | <.01 | 1.18 | 0.09 | 0.05 | .04 | 1.10 | 0.04 | 0.06 | .51 | 1.04 |

| Control variables | ||||||||||||

| Participant: Genderb | −0.06 | 0.18 | .73 | 0.94 | −0.16 | 0.16 | .30 | 0.85 | −0.27 | 0.18 | .13 | 0.76 |

| Participant: Age | 0.01 | 0.02 | .49 | 1.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 | .54 | 0.99 | −0.02 | 0.02 | .39 | 0.98 |

| Participant: Years of education | 0.10 | 0.05 | .04 | 1.11 | 0.08 | 0.04 | .04 | 1.09 | 0.10 | 0.05 | .04 | 1.10 |

| Participant: Healthc | 0.15 | 0.10 | .14 | 1.16 | 0.07 | 0.08 | .40 | 1.08 | 0.12 | 0.10 | .23 | 1.13 |

| Participant: Minority statusd | −0.09 | 0.21 | .68 | 0.92 | −0.02 | 0.18 | .93 | 0.98 | −0.05 | 0.20 | .80 | 0.95 |

| Family member: Genderb | −0.49 | 0.09 | <.001 | 0.62 | −0.37 | 0.09 | <.001 | 0.69 | −0.51 | 0.11 | <.001 | 0.60 |

| Family member: Distancee | −0.17 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.84 | −0.18 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.84 | −0.46 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.63 |

| Random effects | ||||||||||||

| Intercept VAR (Level 2: Day) | 0.16 | 0.08 | .04 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.10 | .37 | |||

| Intercept VAR (Level 3: Participant) | 1.10 | 0.17 | <.001 | 0.73 | 0.12 | <.001 | 0.89 | 0.15 | <.001 | |||

| −2 (pseudo) log-likelihood | 21197.43 | 20768.20 | 23190.40 | |||||||||

Note: Participant N = 191; Day N = 1,261; Family member N = 707 (offspring n = 454; parent n = 253). VAR = variance.

a0 = offspring generation, 1 = parent generation.

b0 = female, 1 = male.

c1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, 5 = excellent.

d0 = non-Hispanic white, 1 = racial/ethnic minority.

eDistance in miles using a log transformation.

Affection and Rewards

We considered positive relationship quality and rewards of providing support to explain daily support (Table 5). Middle-aged adults were more likely to give emotional support, advice, and practical help to family members they get along with better. For each point of higher rated relationship quality, the odds of receiving support were 1.64, 1.44, and 1.42 as likely, respectively. Rewards of helping the other party were not associated with daily support.

Table 5.

Logistic Multilevel Models for Each Type of Daily Support Participants Provide by Affection and Rewards of Helping Family Members

| Emotional support | Advice | Practical help | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | p value | Odds ratio | B | SE | p value | Odds ratio | B | SE | p value | Odds ratio | |

| Fixed effects | ||||||||||||

| Intercept | −4.71 | 1.30 | <.001 | −2.45 | 1.10 | .03 | −2.61 | 1.24 | .04 | |||

| Generationa | −0.25 | 0.09 | <.01 | 0.78 | −0.61 | 0.09 | <.001 | 0.55 | −0.23 | 0.11 | .04 | 0.80 |

| Positive relationship qualityb | 0.49 | 0.08 | <.001 | 1.64 | 0.36 | 0.07 | <.001 | 1.44 | 0.35 | 0.09 | <.001 | 1.42 |

| Rewards of helping family memberc | 0.08 | 0.07 | .27 | 1.08 | 0.11 | 0.07 | .08 | 1.12 | 0.06 | 0.08 | .41 | 1.07 |

| Control variables | ||||||||||||

| Participant: Genderd | −0.11 | 0.19 | .56 | 0.90 | −0.19 | 0.16 | .23 | 0.82 | −0.28 | 0.18 | .12 | 0.76 |

| Participant: Age | 0.00 | 0.02 | .95 | 1.00 | −0.02 | 0.02 | .18 | 0.98 | −0.02 | 0.02 | .32 | 0.98 |

| Participant: Years of education | 0.10 | 0.05 | .03 | 1.11 | 0.09 | 0.04 | .03 | 1.10 | 0.09 | 0.05 | .04 | 1.10 |

| Participant: Healthe | 0.07 | 0.10 | .52 | 1.07 | 0.02 | 0.09 | .86 | 1.02 | 0.04 | 0.10 | .69 | 1.04 |

| Participant: Minority statusf | −0.10 | 0.22 | .66 | 0.91 | −0.06 | 0.18 | .73 | 0.94 | −0.06 | 0.20 | .75 | 0.94 |

| Family member: Genderd | −0.39 | 0.09 | <.001 | 0.68 | −0.26 | 0.09 | <.01 | 0.77 | −0.47 | 0.11 | <.001 | 0.63 |

| Family member: Distanceg | −0.19 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.83 | −0.20 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.82 | −0.48 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.62 |

| Random effects | ||||||||||||

| Intercept VAR (Level 2: Day) | 0.19 | 0.08 | .02 | 0.19 | 0.08 | .01 | 0.09 | 0.10 | .32 | |||

| Intercept VAR (Level 3: Participant) | 1.20 | 0.18 | <.001 | 0.79 | 0.13 | <.001 | 0.90 | 0.15 | <.001 | |||

| −2 (pseudo) log-likelihood | 21096.83 | 20639.59 | 23014.39 | |||||||||

Note: Participant: N = 191; Day N = 1,261; Family member N = 707 (offspring n = 454; parent n = 253). VAR = variance.

a0 = offspring generation, 1 = parent generation.

bMean scores of 2 items rated 1 = not at all to 5 = a great deal.

cRated 1 = not at all to 5 = a great deal.

d0 = female, 1 = male.

e1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, 5 = excellent.

f0 = non-Hispanic white, 1 = racial/ethnic minority.

gDistance in miles using a log transformation.

Competition for Support

We also examined competition for support (Table 6). The pool of family members (e.g., number of grown children, number of parents) was negatively associated with emotional support and advice. A grown child or a parent in a larger family was less likely to receive advice or emotional support on a given day. For example, in families with two children, family members were 1.18 times as likely to receive emotional support than in families with three children, and similar comparisons for families with 4 children versus 3 or 2 versus 1 child. In families with one parent (rather than two parents), family members were 1.69 times as likely to receive emotional support and 1.40 times as likely to receive advice. Whether a participant supported another family member that day was not systematically associated with support to a grown child or parent.

Table 6.

Logistic Multilevel Models for Each Type of Daily Support Participants Provide by Competition for Support

| Emotional support | Advice | Practical help | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | p value | Odds ratio | B | SE | p value | Odds ratio | B | SE | p value | Odds ratio | |

| Fixed effects | ||||||||||||

| Intercept | −1.07 | 1.28 | .40 | 0.30 | 1.04 | .77 | −0.41 | 1.25 | .74 | |||

| Generationa | −0.21 | 0.10 | .03 | 0.81 | −0.52 | 0.09 | <.001 | 0.59 | −0.16 | 0.12 | .16 | 0.85 |

| Participant: Number of living children | −0.16 | 0.07 | .02 | 0.85 | −0.16 | 0.06 | <.01 | 0.85 | −0.07 | 0.07 | .27 | 0.93 |

| Participant: Number of living parents | −0.53 | 0.19 | <.01 | 0.59 | −0.33 | 0.16 | .04 | 0.72 | −0.30 | 0.19 | .11 | 0.74 |

| Helped other child that dayb | −0.08 | 0.10 | .43 | 0.93 | 0.02 | 0.09 | .80 | 1.02 | 0.06 | 0.11 | .61 | 1.06 |

| Helped other parent that dayc | 0.04 | 0.11 | .70 | 1.04 | 0.28 | 0.10 | <.01 | 1.32 | 0.23 | 0.12 | .06 | 1.26 |

| Helped any others that dayd | 0.59 | 0.11 | <.001 | 1.80 | 0.31 | 0.10 | <.01 | 1.36 | 0.19 | 0.12 | .10 | 1.21 |

| Control variables | ||||||||||||

| Participant: Gendere | −0.13 | 0.18 | .47 | 0.88 | −0.20 | 0.15 | .17 | 0.82 | −0.26 | 0.17 | .14 | 0.77 |

| Participant: Age | 0.00 | 0.02 | .79 | 1.00 | −0.02 | 0.02 | .14 | 0.98 | −0.02 | 0.02 | .22 | 0.98 |

| Participant: Years of education | 0.08 | 0.05 | .08 | 1.08 | 0.08 | 0.04 | .05 | 1.08 | 0.09 | 0.04 | .04 | 1.10 |

| Participant: Healthf | 0.13 | 0.10 | .19 | 1.14 | 0.06 | 0.08 | .49 | 1.06 | 0.08 | 0.10 | .37 | 1.09 |

| Participant: Minority statusg | −0.06 | 0.20 | .77 | 0.94 | −0.05 | 0.17 | .78 | 0.96 | −0.02 | 0.20 | .92 | 0.98 |

| Family member: Gendere | −0.50 | 0.09 | <.001 | 0.61 | −0.37 | 0.09 | <.001 | 0.69 | −0.58 | 0.11 | <.001 | 0.56 |

| Family member: Distanceh | −0.19 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.83 | −0.20 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.82 | −0.49 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.62 |

| Random effects | ||||||||||||

| Intercept VAR (Level 2: Day) | 0.15 | 0.11 | .15 | 0.07 | 0.10 | .46 | — | — | — | |||

| Intercept VAR (Level 3: Participant) | 1.00 | 0.17 | <.001 | 0.60 | 0.11 | <.001 | 0.82 | 0.14 | <.001 | |||

| −2 (pseudo) log-likelihood | 21372.15 | 20957.66 | 23423.36 | |||||||||

Note: Participant N = 191; Day N = 1,261; Family member N = 707 (offspring n = 454; parent n = 253). VAR = variance.

a0 = offspring generation, 1 = parent generation.

bOffered any type of help (advice, emotional, practical) to another child.

cOffered any type of help (advice, emotional, practical) to another parent.

dOffered any type of help (advice, emotional, practical) to anyone else.

e0 = female, 1 = male.

f1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, 5 = excellent.

g0 = non-Hispanic white, 1 = racial/ethnic minority.

hDistance in miles using a log transformation.

Providing Support and Daily Mood

MLMs assessed effects of providing support to family members on daily mood. Predictors were providing each type of support that day to any grown child or any parent (Table 7). Participants experienced more positive mood on days when they provided emotional support or advice to a grown child. By contrast, providing any type of support to an aging parent was associated with more negative mood. These effects were evident for same day mood; lagged effects of providing support on next day’s mood were not significant (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 7.

Multilevel Models Predicting Participant’s Daily Mood From Providing Daily Support to Family Members

| Positive mood | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional support | Advice | Practical help | |||||||

| B | SE | p value | B | SE | p value | B | SE | p value | |

| Fixed effects | |||||||||

| Intercept | 2.68 | 0.48 | <.001 | 2.67 | 0.49 | <.001 | 2.72 | 0.49 | <.001 |

| Support given to offspringa | 0.07 | 0.03 | .01 | 0.07 | 0.02 | <.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | .77 |

| Support given to parenta | −0.03 | 0.03 | .32 | −0.01 | 0.03 | .81 | −0.04 | 0.04 | .35 |

| Control variables | |||||||||

| Age | 0.01 | 0.01 | .37 | 0.01 | 0.01 | .38 | 0.01 | 0.01 | .42 |

| Genderb | 0.01 | 0.07 | .93 | 0.00 | 0.07 | .96 | 0.00 | 0.07 | .96 |

| Years of education | −0.04 | 0.02 | .05 | −0.04 | 0.02 | .04 | −0.04 | 0.02 | .05 |

| Healthc | 0.17 | 0.04 | <.001 | 0.18 | 0.04 | <.001 | 0.18 | 0.04 | <.001 |

| Minority statusd | 0.17 | 0.08 | .04 | 0.17 | 0.08 | .04 | 0.16 | 0.08 | .05 |

| Number of children | 0.01 | 0.03 | .83 | 0.01 | 0.03 | .81 | 0.01 | 0.03 | .75 |

| Random effects | |||||||||

| Intercept VAR | 0.21 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.21 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.21 | 0.02 | <.001 |

| Residual VAR | 0.13 | 0.01 | <.001 | 0.13 | 0.01 | <.001 | 0.13 | 0.01 | <.001 |

| −2 log-likelihood | 1524.9 | 1523.4 | 1530.3 | ||||||

| Negative mood | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | p value | B | SE | p value | B | SE | p value | |

| Fixed effects | |||||||||

| Intercept | 2.23 | 0.43 | <.001 | 2.16 | 0.42 | <.001 | 2.21 | 0.43 | <.001 |

| Support given to offspringa | 0.02 | 0.02 | .26 | 0.03 | 0.02 | .08 | 0.01 | 0.02 | .57 |

| Support given to parenta | 0.07 | 0.02 | <.01 | 0.06 | 0.03 | .02 | 0.06 | 0.03 | .02 |

| Control variables | |||||||||

| Age | −0.01 | 0.01 | .09 | −0.01 | 0.01 | .12 | −0.01 | 0.01 | .09 |

| Genderb | −0.04 | 0.06 | .56 | −0.03 | 0.06 | .60 | −0.04 | 0.06 | .56 |

| Years of education | 0.00 | 0.02 | .98 | 0.00 | 0.02 | .99 | 0.00 | 0.02 | .96 |

| Healthc | −0.08 | 0.03 | .02 | −0.08 | 0.03 | .02 | −0.08 | 0.03 | .02 |

| Minority statusd | 0.08 | 0.07 | .28 | 0.08 | 0.07 | .28 | 0.07 | 0.07 | .30 |

| Number of children | −0.02 | 0.02 | .52 | −0.02 | 0.02 | .48 | −0.02 | 0.02 | .48 |

| Random effects | |||||||||

| Intercept VAR | 0.17 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.17 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.17 | 0.02 | <.001 |

| Residual VAR | 0.07 | 0.00 | <.001 | 0.07 | 0.00 | <.001 | 0.07 | 0.00 | <.001 |

| −2 log-likelihood | 790.0 | 791.6 | 794.5 | ||||||

Note: Participant N = 191; Day N = 1,261. VAR = variance.

aSee the column header for the type of support; Column 1 shows the association between emotional support and positive mood, the next columns show the association between advice and positive mood and so forth.

b0 = female, 1 = male.

c1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, 5 = excellent.

d0 = non-Hispanic white, 1 = racial/ethnic minority.

Discussion

Studies using diary methodologies have rarely focused on adults and their parents, despite the importance of these ties in adults’ lives (for exceptions, see Cichy et al., 2014; Savla, Almeida, Davey, & Zarit, 2008). In global retrospective ratings, middle-aged adults report providing support to generations above and below at least once a month (Fingerman et al., 2011; Grundy & Henretta, 2006). Daily diary reports capture less salient events that may not stand out in memory. Nearly all participants in this study provided support to grown children (e.g., emotional, advice, practical help) and over half did so for a parent during the study week. As such, mundane advice and emotional support appear to occur more frequently than previously thought. Moreover, everyday support reflects needs, affection, and (lack of) competition for such support from family members.

Providing support is not a neutral experience for middle-aged adults. Middle-aged adults reported more positive mood on days when they helped grown children. By contrast, supporting parents was draining and associated with more negative mood.

Generational Differences in Support

Research using retrospective reports finds intergenerational support typically flows from parents to grown children (Albertini, Kohli, & Vogel, 2007; Fingerman et al., 2011; Grundy & Henretta, 2006). Moreover, researchers have noted a trend of increased support from middle-aged parents to grown children over the past decade (Fingerman, Cheng, Tighe, Birditt, & Zarit, 2012b) and this support enhances offspring’s well-being (Fingerman et al., 2012c). As young adults encounter daily challenges, parents may offer support that mitigates the effects of stress. Future research should examine the effects of everyday support on grown children by considering both the children’s daily mood and their overall adjustment associated with receipt of everyday support from parents. Daily approaches capture smaller events and give a fuller picture of how these relationships may be intertwined.

Explanations for Daily Support

Findings were consistent with Eggebeen and Davey’s (1998) premise regarding contingency theory. Regardless of generation of family member, middle-aged adults responded to life problems (e.g., divorce, job loss, death of a loved one) with nearly daily advice and emotional support. Consistent with prior studies, parents gave more support to family members who were not married (Suitor et al., 2006) fulfilling social needs in the absence of a romantic partner. Family members with disabilities received practical help. The needs were not evenly distributed, however. For example, rates of disability were considerably higher among respondents’ older parents than their grown children. Moreover, we only assessed a limited set of structural factors and problems that generate needs. Notably, grown children were more likely to receive support than older parents were; although needs may play a role, other factors were important, too.

Middle-aged adults were also more likely to help family members for whom they felt greater affection. According to the generational stake, parents are more invested in their children, and parents experience greater affection for their children than the reverse (Giarrusso et al., 2005). Such investment may contribute to everyday support. Initial comparisons of the sample in the diary study to the broader sample of the Family Exchanges Study revealed that diary participants reported poorer relationship quality. As such, findings of this study may be conservative regarding the frequency of everyday support to grown children; the remaining sample that did not participate may experience even more frequent support.

We had initially predicted that support to another family member each day would affect support to a given parent or child through resource depletion (Strohschein et al, 2008). Yet, in general, support to another person was not associated with whether a parent or child received support that day. Family members in larger families (e.g., more children, more living parents) were less likely to receive everyday support. When middle-aged adults provide assistance to one family member, they may diminish support to other family members due to actual time demands or psychic strain. Alternately, other mechanisms such as sibling support may account for less support from parents in larger families.

Providing Support to Family Members and Daily Mood

Providing support to grown children was associated with better daily mood. The increase in positive mood may reflect generativity or feeling useful to the next generation (Byers et al., 2008; Erikson, 1963). Emotional support and advice also may increase feelings of intimacy in the tie, which contribute to a more positive mood at the end of the day.

By contrast, support to parents was associated with negative mood. Participants helped parents who incurred health declines and disability. As such, offspring may experience thoughts about parental mortality associated with sadness and anxiety (Cicirelli, 1988). Providing such help may be tiring and demanding. Moreover, research has shown that aging parents suffer depressive symptoms when they over benefit from grown children’s support (Davey & Eggebeen, 1998), and such parental reactions to receiving support may be associated with the child’s poorer mood. Even when parents are not disabled and not depressed, middle-aged adults may find giving everyday support to aging parents taxing (Savla et al., 2008). Future research should pursue explanations for disparate patterns regarding support to parents and grown children and daily mood, including the types of support, time commitments, and whether middle-aged adults consider such support normative. Moreover, inclusion of the aging parents’ and grown children’s daily mood and overall adjustment would enhance understanding of this tie.

The study has several limitations. Although we obtained information about several types of support to all children and each parent, we did not gather information about the time committed to support. Picking up something at the store for your mother was treated the same as spending an entire day helping a child move. This study is an important first step in understanding everyday support, but future studies should utilize experience sampling or end-of-day reports to capture the amount of time spent supporting family members throughout the day.

Nonetheless, this study provided important information about everyday support. Minor forms of support underlie the ebb and flow of daily life in intergenerational ties. Middle-aged adults provided help more frequently than revealed in prior studies using global retrospective reports. These findings may reflect differences between mundane and fleeting support reported on a daily basis, and more weighty support that is periodic, stands out in memory, and is captured by questions asking about longer time periods. Furthermore, these everyday emotional support, advice, and practical help contribute to daily well-being and may also influence longer term well-being.

Supplementary Material

Please visit the article online at http://gerontologist.oxfordjournals.org/ to view supplementary material.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging, R01AG027769, Family Exchanges Study II, Psychology of Intergenerational Transfers (Karen L. Fingerman, Principal investigator). The MacArthur Network on an Aging Society (John W. Rowe, Network director) provided funds. This research also was supported by grant, 5 R24 HD042849, awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Supplementary Material

References

- Albertini M. Kohli M., & Vogel C (2007). Intergenerational transfers of time and money in European families: Common patterns–different regimes? Journal of European Social Policy, 17, 319–334. doi:10.1177/0958928707081068 [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel C. S. Pearlin L. I. Mullan J. T. Zarit S. H., & Whitlatch C. J (1995). Profiles in caregiving: The unexpected career. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett J. J., & Schwab J (2012). The Clark University Poll of emerging adults. Worcester, MA: Clark University. [Google Scholar]

- Bassett S. S., Folstein M. F. (1991). Cognitive impairment and functional disability in the absence of psychiatric diagnosis. Psychological Medicine, 21, 77–84. doi:10.1017/S0033291700014677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birditt K. S. (2014). Age differences in emotional reactions to daily negative social encounters. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69, 557–566. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbt045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birditt K. S. Fingerman K. L., & Zarit S. H (2010). Adult children’s problems and successes: Implications for intergenerational ambivalence. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Science, 65, 145–153. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbp125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucx F. van Wel F., & Knijn T (2012). Life course status and exchanges of support between young adults and parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 101–115. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00883.x [Google Scholar]

- Byers A. L., Levy B. R., Allore H. G., Bruce M. L., Kasl S. V. (2008). When parents matter to their adult children: Filial reliance associated with parents’ depressive symptoms. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63, P33–P40. doi:10.1093/geronb/63.1.P33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cichy K. E., Stawski R. S., Almeida D. M. (2012). Racial differences in exposure and reactivity to daily family stressors. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 74, 572–586. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00971.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cichy K. E., Stawski R. S., Almeida D. M. (2014). A double-edged sword: Race, daily family support exchanges, and daily well-being. Journal of Family Issues, 35, 1824–1845. doi:10.1177/0192513X13479595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicirelli V. G. (1988). A measure of filial anxiety regarding anticipated care of elderly parents. The Gerontologist, 28, 478–482. doi:10.1093/geront/28.4.478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey A., Eggebeen D. J. (1998). Patterns of intergenerational exchange and mental health. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 53, P86–P95. doi:10.1093/geronb/53B.2.P86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio J. F. Piliavin J. A. Schroeder D. A., & Penner L. A (2006). The social psychology of prosocial behavior. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Eggebeen D. J., & Davey A (1998). Do safety nets work? The role of anticipated help in times of need. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60, 939–950. doi:10.2307/353636 [Google Scholar]

- Erikson E. H. (1963). Childhood and society (2nd ed.). New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman K. L., Cheng Y.-P., Birditt K., Zarit S. (2012). Only as happy as the least happy child: Multiple grown children’s problems and successes and middle-aged parents’ well-being. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67, 184–193. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbr086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman K. L. Cheng Y.-P. Tighe L. Birditt K. S., & Zarit S (2012. b). Relationships between young adults and their parents. In Booth A. Brown S. L. Landale N. Manning W., & McHale S. M. (Eds.), Early adulthood in a family context (pp. 59–85). New York: Springer Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman K. L. Cheng Y.-P. Wesselmann E. D. Zarit S. Furstenberg F., & Birditt K. S (2012. c). Helicopter parents and landing pad kids: Intense parental support of grown children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 880–896. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00987.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman K., Miller L., Birditt K., Zarit S. (2009). Giving to the Good and the Needy: Parental Support of Grown Children. Journal of marriage and the family, 71, 1220–1233. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00665.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman K. L. Pitzer L. M. Chan W. Birditt K. S. Franks M. M., & Zarit S. H (2011). Who gets what and why: Help middle-aged adults provide to parents and grown children. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 66, 87–98. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbq009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg F. F. (2010). On a new schedule: Transitions to adulthood and family change. The Future of Children, 20, 67–87. doi:10.1353/foc.0.0038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giarrusso R. Feng D., & Bengtson V. L (2005). The intergenerational stake over 20 years. In Silverstein M. (Ed.), Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics (pp. 55–76). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman C. R. Steiner V., & Zarit S. H (1997). Personal orientation as a predictor of caregiver strain. Aging and Mental Health, 1, 149–157. doi:10.1080/13607869757245 [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield E. A., Marks N. F. (2006). Linked lives: Adult children’s problems and their parents’ psychological and relational well-being. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 68, 442–454. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00263.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy E. (2005). Reciprocity in relationships: Socio-economic and health influences on intergenerational exchanges between Third Age parents and their adult children in Great Britain. The British Journal of Sociology, 56, 233–255. doi:10.1111/j.1468-4446.2005.00057.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy E., & Henretta J. C (2006). Between elderly parents and adult children: A new look at the ‘sandwich generation.’ Aging and Society, 26, 707–722. doi:10.1017/S0144686X06004934 [Google Scholar]

- Ha J.-H. Carr D. Utz R., & Ness R (2006). Older adults’ perceptions of intergenerational support after widowhood: How do men and women differ? Journal of Family Issues, 27, 3–30. doi:10.1177/0192513X05277810 [Google Scholar]

- Hartnett C. S., Furstenberg F., Birditt K., Fingerman K. (2013). Parental support during young adulthood: Why does assistance decline with age? Journal of Family Issues, 34, 975–1007. doi:10.1177/0192513X12454657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler E. L., Kasl S. (1991). Health perceptions and survival: Do global evaluations of health status really predict mortality? Journal of Gerontology, 46, S55–S65. doi:10.1093/geronj/46.2.S55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. K. (2013). Parental Financial Assistance and Young Adults’ Relationships With Parents and Well-Being. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 75, 713–733. doi:10.1111/jomf.12029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohli M. (2005). Intergenerational transfers and inheritance: A comparative view. In Silverstein M., Schaie K. W. (Eds.), Intergenerational relations across time and place: Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics (pp. 266–289). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Martini T. S., Grusec J. E., Bernardini S. C. (2003). Perceptions of help given to healthy older mothers by adult daughters: Ways of initiating help and types of help given. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 57, 237–257. doi:10.2190/WXQ7-XPP8-F0H7-Q2KR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis H. (2012). Why researchers should think “real world”: A conceptual rationale. In Mehl M. R., Conner T. S. (Eds.), Handbook of research methods for studying daily life (pp. 3–21). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Savla J., Almeida D. M., Davey A., Zarit S. H. (2008). Routine assistance to parents: Effects on daily mood and other stressors. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63B, S154–S161. doi:10.1093/geronb/63.3.S154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz B. Trommsdorff G. Albert I., & Mayer B (2005). Adult parent-child relationships: Relationship quality, support, and reciprocity. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 54, 396–417. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2005.00217.x [Google Scholar]

- Sechrist J., Suitor J. J., Howard A. R., Pillemer K. (2014). Perceptions of Equity, Balance of Support Exchange, and Mother-Adult Child Relations. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 76, 285–299. doi:10.1111/jomf.12102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer M. M., Almeida D. M., Greenberg J. S., Savla J., Stawski R. S., Hong J., Taylor J. L. (2009). Psychosocial and biological markers of daily lives of midlife parents of children with disabilities. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50, 1–15. doi:10.1177/002214650905000101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M. Gans D., & Yang F. M (2006). Intergenerational support to aging parents: The role of norms and needs. Journal of Family Issues, 27, 1068–1084. doi:10.1177/0192513X06288120 [Google Scholar]

- Strohschein L. Gauthier A. H. Campbell R., & Kleparchuk C (2008). Parenting as a dynamic process: A test of resource dilution hypothesis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 670–683. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00513.x [Google Scholar]

- Suitor J. J., Pillemer K., Sechrist J. (2006). Within-family differences in mothers’ support to adult children. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61, S10–S17. doi:10.1093/geronb/61.1.S10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz T. T. (2009). Intergenerational family relations in adulthood: Patterns, variations, and implications in the contemporary United States. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 191–212. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134615 [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D. (1992). Relationships between adult children and their parents: Psychological consequences for both generations. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 544, 664–674. doi:10.2307/353252 [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. (2012). 2012 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates: Marital Status (S1201). Retrieved from http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_12_1YR_S1201&prodType=table [Google Scholar]

- Vaux A. (1988). Social support: Theory, research, and intervention. New York: Praeger Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D., Clark L. A., Tellegen A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6. 1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.