Abstract

The 7th ASM Conference on Biofilms was held in Chicago, Illinois, from 24 to 29 October 2015. The conference provided an international forum for biofilm researchers across academic and industry platforms, and from different scientific disciplines, to present and discuss new findings and ideas. The meeting covered a wide range of topics, spanning environmental sciences, applied biology, evolution, ecology, physiology, and molecular biology of the biofilm lifestyle. This report summarizes the presentations with regard to emerging biofilm-related themes.

INTRODUCTION

The 7th American Society for Microbiology Conference on Biofilms was held in downtown Chicago, Illinois, from 24 to 29 October 2015. The meeting covered an exciting range of topics across the scope of biofilm research and comprised 4 keynote lectures and 72 talks in 13 thematically organized sessions. The meeting also included two extensive poster sessions that featured 304 posters. In this review, we attempt to convey the depth and breadth of the topics that were presented during Biofilms 2015 and to provide a synopsis of recent developments and emerging trends in the field.

Biofilms are matrix-enclosed single or multispecies microbial communities that can form on virtually any surface. Biofilms form in most natural or engineered systems, with both positive and negative impacts. The composition and physical structure of biofilms reflect a multitude of complex interactions that take place at different levels between the biofilm constituents and their environment; thus, the study of many intrinsic functions and attributes of biofilms now encompasses multiple research fields. The ASM Biofilms 2015 conference highlighted the need to employ multidisciplinary approaches to advance fundamental and applied research on clinical, industrial, and environmental biofilm systems.

The conference was preceded by three parallel and highly attended hands-on workshops on models and approaches to study, image, and quantify biofilms and biofilm infections in vitro and in vivo. For many, these workshops provided an excellent introduction to the 4-day conference, which comprised a comprehensive and wide-ranging scientific program organized by a committee composed of 10 international biofilm experts. Overall, the program was built around 13 thematic sessions, each comprising a series of 25-min talks given by a mix of invited speakers and speakers selected from authors of abstracts submitted to the scientific committee.

BIOFILM COMMUNITIES IN NATURE

The conference was launched by the keynote lecture delivered by Dianne Newmann (California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA), who gave an overview of the complex biological and physico-chemical parameters that define different biofilm lifestyles. Dr. Newmann discussed the importance of using environmentally informed reductionist approaches to study biofilms, using examples drawn from her work on bacterial growth and metabolism in the microenvironment of cystic fibrosis sputum. These studies revealed that bacterial growth rates, on average, are far lower than those typically studied in the laboratory (1). By performing a proteomic study of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to determine which proteins are actively being made under anaerobic survival conditions, she described the discovery of a small, acidic protein, SutA (survival under transitions), that is posttranscriptionally upregulated during slow growth. SutA associates with RNA polymerase and regulates the expression of genes required for ribosome biogenesis and others involved in biofilm development, secondary metabolite production, and fitness under fluctuating conditions (2). With this insight underscoring the importance of studying biofilm properties beyond the lab, the first session provided a basis for understanding processes involving the formation of biofilms and the dynamics of different naturally occurring biofilm communities. Matthew Powers (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC) explored the interactions between a mixed consortia of 29 bacteria isolated from roots of the plant Arabidopsis thaliana. His work identified combinations of different species that exhibit both cooperative and competitive interactions. Combined with matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (MS) to generate metabolic profiles of each of these cultures, this approach was highlighted as a method that can be used to better understand chemical signaling between mixed species communities.

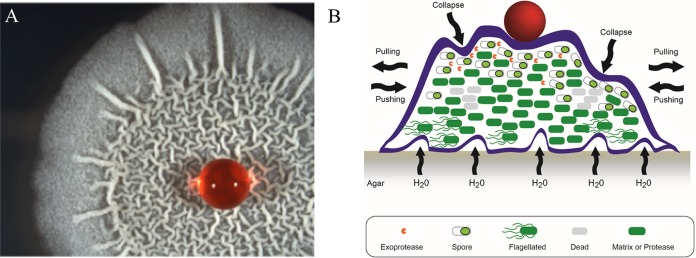

In a thought-provoking presentation, Roman Stocker (ETH, Zurich, Switzerland) showed that coexistence of marine vibrios on the surface of marine particles depends on a trade-off between the opposing phenotypes of adhesion and dispersion in nutrient-variable oceanic environments (Fig. 1). Under high-nutrient conditions, population specialization favoring attachment and growth is promoted, while under limiting-nutrient conditions, there is a switch to a dispersal mode of growth (3). Deborah Hogan (Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH) explored Candida albicans-P. aeruginosa interactions in the context of cystic fibrosis lung infection. Using a powerful machine learning approach (4) to explore large-scale analysis of P. aeruginosa gene expression patterns, Dr. Hogan described how ethanol production by C. albicans stimulates cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) synthesis and the formation of P. aeruginosa biofilms, which in turn produce phenazines that enhance ethanol production. This positive-feedback loop provides insight into why coinfection with both P. aeruginosa and C. albicans is associated with poor outcomes in cystic fibrosis (5). Mark Mandel (Northwestern University, Chicago, IL) described how a functional genomics approach led to the identification of novel positive and negative regulators of biofilm development, including chaperone protein DnaJ and the histidine kinase BinK, which are required for robust in vivo colonization of the light organ of Euprymna scolopes squid by Vibrio fischeri bacteria (6). Stephen Lindemann (Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, WA) concluded this session dedicated to naturally occurring environmental biofilms by presenting a study of nitrogen flux into phototrophic microbial mats, showing that nitrogen limitation is species specific and that the spatial organization and partitioning of carbon between autotrophs and heterotrophs in cyanobacterial biofilms depend upon the form of nitrogen species being assimilated.

FIG 1.

Biofilm formation and cell dispersal on marine particles. The cartoon depicts different strategies of marine bacteria for the utilization of marine particles. Many bacteria in the ocean are motile and chemotactic (red and blue cells), but only some populations can attach to and form biofilms on marine particles (red cells), whereas others hover in the vicinity of particles and obtain fewer nutrients but in return can rapidly disperse to colonize new particles (blue cells). (Courtesy of Yutaka Yawata, Glynn Gorick, and Roman Stocker; reproduced with permission.)

Together, these talks provided a deeper understanding of the roles and activities of organisms within single-species and multispecies biofilms in the natural environment, as well as approaches to effectively study biofilms despite the complexity of the environments in which they are found.

BACTERIAL ADHESION FACTORS AND THE PLANKTONIC TO BIOFILM LIFESTYLE SWITCH

Understanding how free-living planktonic bacteria switch to a sessile mode of growth is still a topic of intense scrutiny and a traditional staple of all recent ASM biofilm conferences. Two sessions were dedicated to this topic, largely dominated by the question of how regulation of adhesion factors and signaling networks involving c-di-GMP and other external signals contributes to this switch.

In the first session dedicated to the transition from planktonic to biofilm lifestyle, Clay Fuqua (Indiana University, Bloomington, IN) described a novel signaling pathway controlling Agrobacterium tumefaciens biofilm formation involving small metabolites called pterins, the first report of their regulatory activity in bacteria. He showed that pterin production by PruA controls surface colonization through the dual-function diguanylate cyclase-phosphodiesterase protein DcpA. The resulting c-di-GMP modulation regulates the production of a unipolar polysaccharide (UPP) adhesin, which is required for A. tumefaciens attachment and biofilm formation (7).

Daniel Kearns (Indiana University, Bloomington, IN) presented data on a new surface contact-dependent cellular differentiation mechanism in Bacillus subtilis, in which flagellar density is controlled by regulatory proteolysis of the master flagellar activator protein SwrA, the master regulator of flagellar biosynthesis, by LonA. It was further shown that LonA-mediated degradation of SwrA happens only in the presence of swarming motility inhibitor A (SmiA). SwrA mutants that were resistant to proteolysis and caused hyperswarming were identified; it was speculated that these mutated residues were required for SmiA interaction (8). Gerard Wong (UCLA, Los Angeles, CA) presented his collaboration with George O'Toole with a surprising finding on surface sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. By tracking the first 20 generations of cells on a surface with single-cell resolution, they showed that surface sensing is an inherently multigenerational phenomenon: Pseudomonas uses the second messenger cyclic AMP (cAMP) as a kind of accumulated memory to signal across generations, such that mechano-sensing of the surface in one generation of cells can lead to flagellum shutdown in cells many generations later (9).

A new aspect of control for the transition between planktonic and biofilm behaviors was presented by Benoît-Joseph Laventie (Biozentrum, Basel, Switzerland), who described a new c-di-GMP effector in P. aeruginosa, identified using capture-compound mass spectrometry (10). This effector, FimA, mediates pilus-mediated attachment and biofilm formation. He showed that in response to a surface, FimA rapidly localizes to the new cell pole in a cdG-dependent manner to facilitate type IV pilus (T4P) assembly and function.

Aretha Fiebig (University of Chicago, Chicago, IL) described how fine-tuning of the Caulobacter crescentus lifestyle depends on the HfiA protein inhibitor, which targets a conserved glycolipid glycosyltransferase (GTF) required for holdfast synthesis. HfiA is regulated by a complex pathway involving kinases that act on the response regulator LirA, possibly in combination with nutritional sensing in different environments (11). Another mechanism involved in the fine-tuning of planktonic and biofilm lifestyles was presented by Alain Filloux (Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom). The HptB pathway is part of the P. aeruginosa GacA/Rsm lifestyle switch that controls biofilm growth. Here it was shown that the HptB control of biofilm formation and motility can be rewired into an original c-di-GMP-dependent network involving a newly identified diguanylate cyclase and effector protein.

In her talk, Sonja Albers (University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany) presented how she used genetic, proteomic, and transcriptomic approaches to study regulation of biofilm formation in Archaea. She identified an archaeon-specific group of regulators, the Lrs14 regulators, which are involved in major cell fate decisions (12). In the crenarchaeon Sulfolobus acidocaldarius, the Lrs14 regulator AbfR1 antagonistically coordinates motility and extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) production during biofilm development. Future work will focus on understanding the entire regulatory network involved in biofilm formation in S. acidocaldarius. Christopher Jones (University of California, Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA) described the identification of a new c-di-GMP receptor, MshE, in Vibrio cholerae. MshE is a polymerizing ATPase that is required for biosynthesis of MshA pili, which is essential for transition from the motile to the sessile lifestyle. MshE c-di-GMP binding activity is dependent on the MshE N-terminal domain, and c-di-GMP affects MshA pilus assembly and function through direct interactions with the MshE (13).

Maria Hadjifranjiskou (Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN) described the application of MALDI-TOF imaging mass spectrometry (IMS) to study uropathogenic Escherichia coli biofilms. Dr. Hadjifranjiskou discussed how oxygen concentration influences the expression of type 1 fimbriae. She showed that the phase-variable fim promoter favored the “on'” orientation in the presence of oxygen, while the “off” orientation was favored under low-oxygen conditions. This illustrates how sensing natural oxygen gradients within biofilms shapes localization of adhesive factors and contributes to the stratification of extracellular matrix components within the biofilm (14). Using atomic force microscopy (AFM), Cécile Formosa-Dague (Catholic University of Louvain, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium) explored the relationship between nanomechanics and adhesion and presented how multiparametric imaging combined with single-cell force spectroscopy can unravel the zinc-dependent adhesive and mechanical properties of the SasG adhesion protein from Staphylococcus aureus. Dr. Formosa-Dague showed that zinc plays a dual role in S. aureus SasG-mediated biofilm formation: it alters the surface properties of the cell to enable the projection of adhesive SasG fibrils beyond other surface components that can in turn mediate specific cell-cell adhesion through the formation of Zn2+-dependent homophilic bonds between β-sheet-rich SasG multidomains on neighboring cells (15). Finally, Inigo Lasa (Public University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain) described the identification and characterization of a short amyloid stretch in the S. aureus Bap protein. When processed and released, Bap beta-amyloid domains self-assemble into amyloid fibrils and induce bacterial aggregation in response to a decrease in pH during stationary-phase growth. This amyloid behavior is inhibited in the presence of calcium, which is thought to induce compaction, limiting access to proteases that modulate its activity (59).

Together, the speakers in this session presented an impressively diverse array of approaches to explore the complex factors and signals involved in surface sensing and early attachment events.

ASSEMBLY AND MODULATION OF THE BIOFILM MATRIX

The biofilm matrix is the glue that holds the cells together. Diverse organisms have evolved a wealth of different strategies for adhering to each other and to surfaces, including the production of amyloid fibers, protein adhesins, and polysaccharides, as well as mechanisms for modulating biofilm matrix production or interactions in response to environmental signals such as oxygen or calcium.

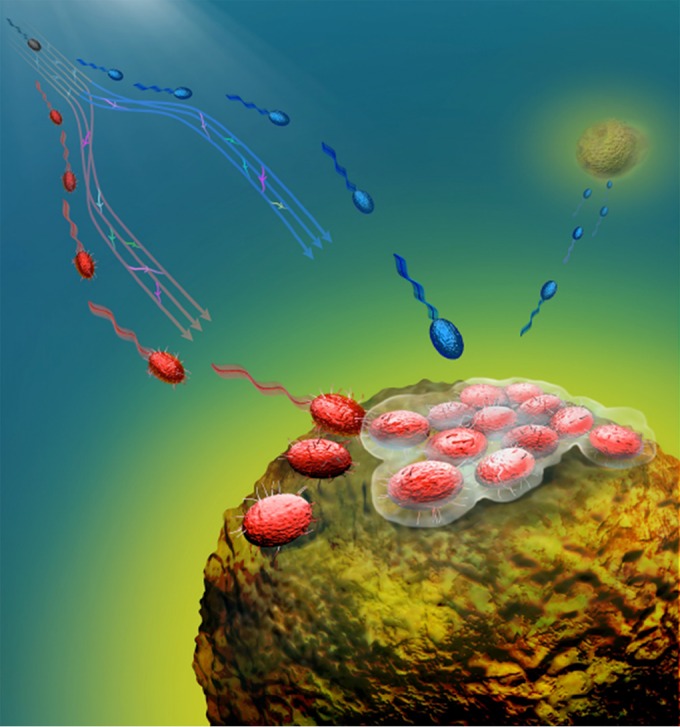

For example, Matt Parsek (University of Washington, Seattle, WA) presented new data on the composition of the PEL polysaccharide, a component of the P. aeruginosa biofilm matrix. Dr. Parsek showed that PEL matrix polymer is a cationic exopolysaccharide rich in N-acetylgalactosamine and N-acetylglucosamine. PEL interacts with extracellular DNA via ionic interactions and could provide a rigid yet extensible EPS shell that can accommodate biofilm growth, like the envelope of an inflating balloon (16). This contribution of the extracellular scaffold to the properties of biofilms was also illustrated by Nicola Stanley-Wall (University of Dundee, Dundee, United Kingdom). Dr. Stanley-Wall described how BslA, a surface-active amphiphilic extracellular protein that self-assembles and changes shape upon interaction with an interface, forms a water-resistant hydrophobic coat around the Bacillus subtilis biofilm and contributes to shielding of the bacterial community by fine-tuning its solvent and interfacial interactions (Fig. 2) (17).

FIG 2.

Hydrophobic nature of wrinkled colonies of Bacillus subtilis. (A) Colony of B. subtilis with a red water droplet. (B) Cartoon depicting a cross-section of the colony and the factors that influence formation of the wrinkles. (Republished from Molecular Biology [57].)

Daniel Wozniak (Ohio State University, Columbus, OH) discussed the respective contributions of P. aeruginosa exopolysaccharides involved in the mucoid (alginate) or small-colony variant (SCV) morphotypes (PEL and PSL) to biofilm biology. Dr. Wozniak presented evidence for an SCV fitness advantage via increased tolerance to antimicrobial and host defenses due to c-di-GMP-dependent aggregation, which then prevents uptake by phagocytic cells and persistence in a porcine chronic wound infection model.

Alexandra Paharik (University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA) discussed how, even in strains of Staphylococcus epidermidis unable to produce surface polysaccharides, the secreted metalloprotease SepA promotes biofilm via proteolytic processing of a cell wall-anchored adhesin called Aap (accumulation-associated protein). Jin Hwan Park (Seoul National University, Seoul, South Korea) reported the characterization of the cabABC operon, which is essential for biofilm development in Vibrio vulnificus. CabA is a calcium-binding protein that is induced by elevated levels of c-di-GMP and secreted in a CabBC-dependent manner. CabA is localized to the biofilm matrix, multimerizes in the presence of calcium, and contributes to the V. vulnificus robust biofilm structure and rugose colony phenotype (18).

Boo Shan Tseng (University of Washington, Seattle, WA; currently at UNLV, Las Vegas, NV) further illustrated that the biofilm matrix can be much more than a structural scaffold. Dr. Tseng used a proteomic approach to investigate the role of biofilm matrix proteins and showed that ecotin, a serine protease inhibitor, is selectively maintained by PSL in the P. aeruginosa biofilm matrix. Ecotin could protect biofilms from proteolytic attack, potentially inhibiting neutrophil elastase, an enzyme produced by the host immune system during respiratory infections.

Fungal biofilms, which are linked to many human infections, were also represented in the meeting. The adherence of organisms such as Candida albicans to implanted medical devices results in biofilms that withstand extraordinarily high antifungal concentrations. Thus, there is a strong need to understand the physiology and molecular dynamics of fungal biofilms. Aaron Mitchell (Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA) introduced us to fungal biofilms formed by C. albicans. He described how Candida biofilm formation can result either from the positive regulation of glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-linked ALS1, ALS3, and HWP1 (through regulators such as Bcr1) or from the inhibition of yeast formation via a negative regulatory cascade that leads to filamentation and transition to the hyphal stage (19). David Andes (University of Wisconsin—Madison, Madison, WI) described how Candida adherence to implanted medical devices can withstand extraordinarily high antifungal concentrations. He showed that the Candida biofilm matrix contains mannan-glucan structures that are distinct from Candida cell wall glucans and can sequester antifungal drugs, therefore contributing to multidrug resistance (19).

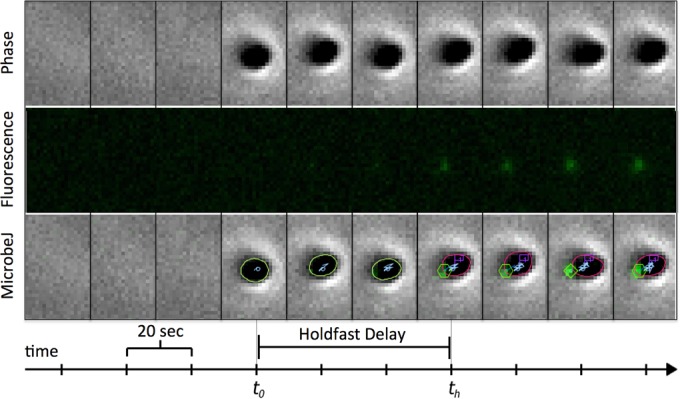

In his keynote address, Yves Brun (Indiana University, Bloomington, IN) brought together the topics addressed by the first four sessions by discussing mechanisms of bacterial surface attachment at the single-cell level (Fig. 3). Drawing from his work on Caulobacter crescentus and other alphaproteobacteria producing holdfast adhesin structures, Dr. Brun discussed the notion of surface sensing, the transition between reversible and irreversible attachment, and the mechanical forces involved in holdfast-surface interaction and in anchoring the holdfast to the cell envelope. These results shed new light on holdfast biophysics and regulation and revisited the role of flagella in surface mechano-sensing, while also providing inspiration for the development of new biologically inspired materials with different adhesion properties (20).

FIG 3.

Automated image analysis of surface contact-stimulated holdfast synthesis in C. crescentus. Phase-contrast images of cells arriving on a glass surface and fluorescence images of lectin staining of the holdfast were taken every 20 min and were analyzed with MicrobeJ (http://www.indiana.edu/∼microbej/) (58, 65). MicrobeJ detects (green outline at t0) and tracks (pale blue) the cell pole and the holdfast (green hexagon at th). User-defined criteria automatically record two temporal events, cell and holdfast detection, and these are used to automatically compute the time delay between cell arrival on the surface and holdfast synthesis.

NEW INSIGHTS INTO ANTIMICROBIAL TOLERANCE AND NOVEL TARGETS AND STRATEGIES TO FIGHT BIOFILM INFECTIONS

The remarkable properties of resistance of biofilms to antimicrobials and host defenses are well known and are likely one factor contributing to the current crisis in the availability of effective antibiotics in the clinic. Understanding the mechanisms that permit biofilm cells to resist or tolerate antibiotics and natural host defenses and also understanding the corresponding response of hosts to biofilm infections are therefore important areas of investigation. Not surprisingly, the development of novel treatments for infections, based on the properties of biofilms, was a prominent theme of the conference.

Recently, it has become apparent that the ability of a subset of cells to become antibiotic-tolerant “persisters” is a key factor affecting antibiotic effectiveness, and thus an active area of research lies in understanding the mechanisms involved in the production of persisters. Kim Lewis (Northeastern University, Boston, MA) covered a decade of work on persister biology and biofilm eradication, including a discussion on how a decrease in the level of ATP, but not toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems, leads to persistence in S. aureus. Dr. Lewis then presented his recent work on the clinical significance of persister enrichment in clinical isolates and the mechanistic basis of heritable, clinically relevant antibiotic tolerance (21). He concluded by presenting his recent work on the discovery of the new antibiotic teixobactin, a cell wall synthesis inhibitor with bactericidal activity against multiple pathogens, including S. aureus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Continuing the theme of antibiotic tolerance, Olga Petrova (Binghamton University, Binghamton, NY) presented results suggesting that P. aeruginosa biofilm formation and biofilm tolerance to antibiotics are regulated by distinct signaling cascades, both involving the transcriptional regulator FleQ and the sensor-regulator hybrid SagS, but with discrete c-di-GMP requirements and protein interaction partners. Separating the factors involved in biofilm formation and biofilm tolerance will allow biofilm control strategies by targeting of the two distinct pathways (22).

Luanne Hall-Stoodley (The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, OH) introduced us to Streptococcus pneumoniae biofilms that colonize adenoid tissues and develop on middle ear mucosal epithelia, contributing to the severity of respiratory infections and chronic otitis. Dr. Hall-Stoodley showed that low doses of nitric oxide affect metabolism and decrease antibiotic tolerance. This suggests that adjunctive treatment with low doses of NO, which do not trigger biofilm dispersal, could reduce antibiotic tolerance in pneumococcal biofilms and improve antibiotic efficacy (60). Another treatment strategy was championed by Bob Hancock (University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada), who made a strong case for the use of broad-spectrum cationic antibiofilm peptides against biofilm infections. Dr. Hancock described the characteristics of lead peptides optimized on exploratory robotized platforms that target the intracellular stringent response signal ppGpp in biofilms. These peptides show synergy with existing antibiotics, work in animal models, and represent promising alternatives to combat resistant biofilm infections (23). Lori Burrows (McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada) gave a thought-provoking presentation that described a new approach to identify novel antibiotic activities. Dr. Burrows reported the identification of several molecules (including thiostrepton) that stimulate P. aeruginosa biofilm formation at subinhibitory concentrations. She used the biofilm inducer phenotype, which likely induces defense responses to sublethal damage, to screen for new antibiotics and new targets in complex Streptomyces extracts (24).

Suzanne Walker (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) described a synthetic lethal approach to map interactions between cell envelope pathways in S. aureus and then used a synthetic lethal chemical screen to identify inhibitors of proteins in an interaction network. Network mapping involved screening a transposon mutant library in the presence of a molecule that specifically targets a step involved in envelope biosynthesis and using transposon sequencing (Tn-Seq) to identify the genes that become essential when this step is inhibited. The synthetic lethal chemical screen led to an inhibitor of DltB, which is involved in teichoic acid d-alanylation. This approach, which can be generalized to other bacteria, can be used to identify new small molecules that could serve as novel drugs or as probes to elucidate biological functions (25). In a continuation of this theme, Hans Steenackers (KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium) discussed the use of approaches based on compound screening and synthetic chemistry to identify biofilm inhibitors with broad spectrum activity. He elaborated on the molecular mode of action of 2-aminoimidazole-based biofilm inhibitors, their low potential for resistance development, and their application in antibiofilm coatings for orthopedic implants (26).

Targeting enzymes involved in production and degradation of exopolysaccharides involved in matrix production may lead to new biofilm control strategies. Jennifer L. Dale (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN) showed that the Enterococcus faecalis glycosyltransferases (GTFs) EpaI and EpaOX are involved in synthesis of a cell wall-associated Epa polysaccharide. A defect in GTFs, and associated Epa synthesis, negatively impacts biofilm formation and leads to decreased structural integrity and susceptibility to antibiotics and bile salts, suggesting that GTFs could be new targets for antimicrobial design. Lynne Howell (Hospital for Sick Children/University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) presented evidence that combinations of glycosyl hydrolases can degrade matrix polysaccharides such as P. aeruginosa PEL or PSL or fungal galactosaminogalactan. These enzymes could be used for prevention or disruption of biofilms in the treatment of chronic microbial infections (61). Nicholas Jakubovics (Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom) presented work demonstrating the effect of l-arginine on intermicrobial interactions driving structure and stratification, including coaggregation and interspecies signaling, in dental biofilms. Interfering with these mechanisms could represent a novel approach to control oral streptococcal biofilms (27). John Gunn (The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH) showed how Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi biofilm formation on gallstones enhances gallbladder carriage. This was demonstrated in a human study and in a new mouse model of carriage. In vitro and in vivo studies also demonstrate involvement of the gallbladder epithelium in carriage. Potential antigenic targets present in gallstone biofilms or the use of biofilm-inhibiting compounds may provide potential new avenues for therapeutic intervention against Salmonella biofilm formation and chronic gallbladder infection (28). Finally, using a high-pressure liquid chromatography–high-resolution accurate mass (HPLC-HRAM) MS untargeted lipidomic-based approach, Skander Hathroubi (Université de Montréal, St-Hyacinthe, Quebec, Canada) discussed how planktonic and biofilm Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae cells differed significantly in lipid A structure and quantity, with larger lipid A molecular entities observed in biofilm cells. This would explain at least in part the weaker ability of A. pleuropneumoniae biofilm cells to stimulate porcine alveolar macrophages (PAMs) (62).

Targeting therapeutics to bacterial amyloids was another important topic that was covered. Fredrik Almqvist (Umea University, Umea, Sweden) discussed nonbiocidal approaches targeting pilus fibers and curli amyloids involved in biofilm formation. Dr. Almqvist described how the discovery and improvement of anti-β-amyloid lead compounds not only could inhibit bacterial biofilm formation but also may inform studies on human amyloid-related diseases (29). Cagla Tukel (Temple University, Philadelphia, PA) showed surprising results suggesting that amyloid-containing biofilms trigger autoimmunity. At least 40% of bacterial species produce amyloid-like proteins that share a quaternary structure, as well as physical and immunological properties, with human amyloids associated with complex diseases such as Alzheimer's disease, prion diseases, and type II diabetes. Hence, bacterial amyloids present in the biofilm extracellular matrix, where they can bind extracellular DNA (eDNA), could induce inflammation and production of anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) as well as antichromatin antibodies, potentially contributing to the progression of autoimmunity (30). In his work, Steven Goodman (Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus, OH) has found that targeting the DNABII family of proteins required for the maintenance of eDNA structure can prevent biofilm formation by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and Burkholderia cenocepacia. Dr. Goodman proposed that eDNA-DNABII could be essential for EPS integrity in many bacteria and represents a universal target for biofilm prevention.

EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES AND BIOFILM APPLICATIONS

One of the highlights of the biofilm meeting was the impressive application of new and high-powered technologies to study biofilms and increase our understanding of different aspects of biofilm biology, including the role and/or identity of small molecules such as oxygen, phenazines, and peptides, the spatial composition of the matrix, and intercellular communication. Lars Dietrich (Columbia University, New York, NY) showed that the wrinkly colony phenotype of P. aeruginosa PA14 correlates with oxygen limitation, regulation of matrix production by PAS domain-containing proteins, and defects in the synthesis of endogenous redox-active antibiotics called phenazines. Measurements of cellular NADH/NAD+ ratios in biofilms support redox-driven regulation of microbial community morphogenesis. His group's results implicate specific P. aeruginosa terminal oxidase complexes in biofilm physiology. Dr. Dietrich described his group's work developing miniaturized redox sensor chips that can be used to map metabolite release by colony biofilms. Mapping of phenazines released from intact colonies revealed unexpected influences of biofilm position on phenazine production (31). Elizabeth Shank (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC) described her research using imaging mass spectrometry (IMS) and fluorescent reporter strains to identify metabolites from complex soil communities that stimulate and repress biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis. In particular, Dr. Shank described how thiocillin (32) and 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol (33) can impact matrix-producing B. subtilis populations and therefore modulate different microbial cellular phenotypes. Nydia Morales-Soto (University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN) used confocal Raman microscopy and secondary ion mass spectrometry imaging to fingerprint quinoline quorum-sensing (QS) molecules during swarming motility and biofilm formation. This approach provided a spatiotemporal map of quorum-sensing-based bacterial communication, revealing the importance of quorum-sensing signals in the early stages of P. aeruginosa biofilm development (34). Vanessa Phelan (University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA) discussed how to identify chemical communication signals in complex microbial communities. Dr. Phelan showed how studying bacterial association in S. aureus and E. coli cocultures revealed new competition phenotypes against P. aeruginosa. A number of lead compounds potentially involved in this growth inhibition were analyzed by tandem mass spectrometry and the Global Natural Product Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) platform, a collaborative crowd-sourced knowledge base and analysis platform.

Lynette Cegelski (Stanford University, Stanford, CA) presented a quantitative approach to define the molecular composition of bacterial biofilms using solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) in two different model systems, E. coli and V. cholerae, revealing the power of this approach in determining differences in matrix constituents (35). Florian Blauert (Karlsruher Institute of Technology [KIT], Karlsruhe, Germany) discussed how noninvasive optical coherence tomography (OCT) allows fast, quantitative, and in situ three-dimensional (3D) analysis of biofilm deformation and how to access material properties of biofilms using OCT (36).

BIOFILMS IN ENGINEERED SYSTEMS

In engineered systems, biofilm formation could be beneficial, resulting in optimally functioning engineered bioreactors and bioremediation of toxic compounds, or detrimental, causing biofouling and biocorrosion. Bruce Logan (Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA) talked about hydrogen and biocatalyzed methane production from the cathode in biofilm-based bioelectrochemical systems. Dr. Logan discussed the functional consequence of inactive or dead cells accumulating over time in anode Geobacter anodireducens biofilms. This accumulation results in a two-layer structure with a live outer layer, responsible for current generation, covering an inactive inner core layer that functions as an electrically conductive matrix (37). Howard Stone (Princeton University, Princeton, NJ) showed how particular flow and surface structure influence bacterial biofilm dynamics. In one vignette, Dr. Stone documented how the interplay of flow and twitching motility of P. aeruginosa led to upstream migration of the bacteria, which has consequences for how the bacteria spread in flow networks. Second, using experiments performed in a microfluidic device, he showed that S. aureus and P. aeruginosa form flow-induced, filamentous 3D biofilm streamers that, over time, bridge the spaces between obstacles. Interestingly, while the presence of surface-attached biofilms exerts a limited impact on flow rates, streamers cause rapid clogging. This suggests that the formation of biofilm streamers, rather that surface biofilms, may be the primary cause of flow reduction in environmental, industrial, and medical systems. In a final vignette, Dr. Stone indicated ways in which flow interacts with quorum sensing (QS) to produce space and time dependence of the QS response (38). Allon Hochbaum (University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA) presented approaches to engineer structure-property relationships in E. coli and P. aeruginosa coculture biofilms through the systematic variation of microfabricated growth substrate topography. Dr. Hochbaum showed that periodically patterned microstructures of growth substrate induce morphological changes in E. coli biofilms and a differential accumulation of indole, thus altering competition dynamics between E. coli and P. aeruginosa. An application of this technology was presented by Ethan Mann (Sharklet Technologies, Inc., Aurora, CO), who discussed how surface characteristics impact biological responses and presented the Sharklet microtopography, a nonbiocidal antibiofilm surface for medical devices (39). Kuang He (ExxonMobil, Annandale, NJ) presented a study on the role of indole signaling in anaerobic biofilm formation using the model sulfate-reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio vulgaris (He et al., submitted). Danielle France (NIST, Boulder, CO) presented data on the anticorrosive influence of Acetobacter aceti biofilms on carbon steel surfaces, suggesting that corrosion inhibition by an acid-producing bacterium could be used as an inexpensive solution to industrial problems. Caitlin Howell (Harvard University, Cambridge, MA; currently at the University of Maine, Orono, ME) presented an overview on the use of immobilized liquid layers as a nontoxic method of controlling biomolecular and microbial attachment on a wide variety of different substrates. Dr. Howell discussed numerous potential applications of the technology, inspired by the slippery surface of the carnivorous pitcher plant, including the prevention of bacterial biofilm adhesion to catheters, the mitigation of stable algal biofilm formation on glass substrates, and the reduction of thrombosis in vivo (40).

These presentations collectively showed that better understanding of biofilm formation in industrial settings will allow improved utilization and control of biofilms.

EVOLUTION IN BIOFILMS AND THE IMPACT OF THE ENVIRONMENT ON BACTERIAL LIFESTYLES

Jintao Liu (University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA) discussed cooperation and competition in B. subtilis biofilms: cells at the biofilm periphery protect cells at the biofilm interior from external attack but also starve them through nutrient consumption. Dr. Liu and colleagues showed that this conflict was resolved by the emergence of long-range metabolic codependence between the two groups of cells. Consequently, the biofilm periphery halted growth periodically, increasing availability of nutrients to the sheltered interior cells and promoting the resilience of biofilms against external attack (41). From the same laboratory, on a related topic, Gurol Suel (University of California, San Diego, San Diego, CA) reported that bacterial potassium ion channels conduct long-range electrical signals within bacterial biofilm communities via spatially propagated waves of depolarization. This coordinates metabolic states among cells in the interior and periphery of the biofilm. The report of a community function for potassium ion channels demonstrates the existence of long-range electrical signaling in biofilms (42). Vaughn Cooper (University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA) shed some light on the evolution of wrinkly small-colony variants during Burkholderia cenocepacia chronic infection. By following the evolution of wrinkly colonies from a smooth B. cenocepacia ancestor, a phenomenon associated with biofilm infections, Dr. Cooper showed that selection favored mutations clustered in the wsp operon (43). Despite phenotypic differences among wrinkly mutants, they shared similar fitness properties in mixed biofilms and acted as early surface colonists, suggesting that strong selective forces drive the colonization of this common niche (44). Daniel López (Institute for Molecular Infectious Biology, Würzburg, Germany) described the evolution of antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus biofilms using intraclonal competition. In the presence of magnesium, the parental strain gave rise sequentially to two physiologically distinct subpopulations, a nonpigmented, quorum-sensing overproducer that overproduces the antibiotic bacteriocin and represses biofilms but spreads better due to increased levels of surfactants, and a pigmented strain with increased resistance to vancomycin due to a thicker cell wall. Evolution of the strains in vivo also occurred in organs with higher magnesium levels and resulted in increased virulence (45).

Joe Harrison (University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada) described the identification of a potentially widespread transposon that encodes a thermosensing diguanylate cyclase, TdcA, which confers thermal control of P. aeruginosa biofilm formation by mediating temperature-dependent changes by the production of c-di-GMP at higher temperatures (37°C) but not at lower temperatures (25°C). TdcA is conserved in other organisms, indicating that temperature-controlled production of c-di-GMP may represent an evolutionary advantage. Ákos Kovács (University of Jena, Jena, Germany) discussed how B. subtilis populations producing costly matrix components as common goods can avoid being out-competed by cheaters in spatially structured environments of colony biofilms (46). Interestingly, cheaters are also excluded from pellicles at the air-liquid interface, but they regain their biofilm incorporation ability after prolonged repeated cocultivation in the presence of the producer population. This illustrates how general adaption to certain growth conditions can benefit a cheater population at the expense of the cooperator population rather than by specific adjustment. Kasper Kragh (University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark) showed that the relative fitness of aggregates depends markedly on the density of surrounding single cells. When competition between aggregates and single cells is low, the aggregate is at a growth disadvantage because of reduced nutrient availability in the aggregate interior. However, when there are many single cells on the surface and competition is high, extending vertically above the surface gives the top of the aggregate a better access to nutrients. These findings suggest that aggregates and their interaction with single cells may play a previously unrecognized role during biofilm initiation and development.

George O'Toole (Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH) delivered the third keynote lecture. Dr. O'Toole discussed the topic of diguanylate cyclases and in particular why so many diguanylate cyclases are required for P. fluorescens biofilm formation. He made a compelling case that the investment of a cell to switch to a biofilm lifestyle requires the existence of multistep regulation checkpoints to control the early events associated with surface interaction. Work by Kurt Dahlstrom, a graduate student in the lab, showed that one mechanism of control for c-di-GMP signaling is via protein-protein interactions (47). Current studies, using Biolog to explore 192 different conditions for each of 53 different c-di-GMP-related mutants, together with bacterial two-hybrid assays, are beginning to explore the broader c-di-GMP network in this microbe.

SOCIAL AND ASOCIAL INTERACTIONS IN BIOFILMS

The Biofilms 2015 conference presentations also reflected an increasing focus on multispecies biofilms and microbe-microbe interactions. Numerous studies were directed at understanding the competition and cooperation that occur between organisms of the same or different species in the context of a shared environment.

Joseph Mougous (University of Washington, Seattle, WA) described a new cytoplasmic type VI secretion effector, Tse6, which slows growth of target cells by degrading the universally essential dinucleotides NAD+ and NADP+. Entry of Tse6 into target cells requires its binding to an essential housekeeping protein, the translation elongation factor Tu (EF-Tu). Understanding these bacterial cell-cell interactions will provide insights into interactions that may be occurring within biofilms (48). Peggy Cotter (University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC) discussed the mechanism of interbacterial signal transduction mediated by contact-dependent growth inhibition (CDI) system proteins. Dr. Cotter described how the Burkholderia thailandensis BcpA protein not only inhibits the growth of “nonself” bacteria by mediating CDI (interbacterial killing) but also contributes to community behaviors in “self” bacteria (those producing the same BcpAIOB proteins) by inducing changes in the expression of genes required for the production of pili and EPS and for biofilm formation (63). These results suggest that CDI system proteins control both cooperative and competitive behaviors to build microbial communities composed of only closely related bacteria (49).

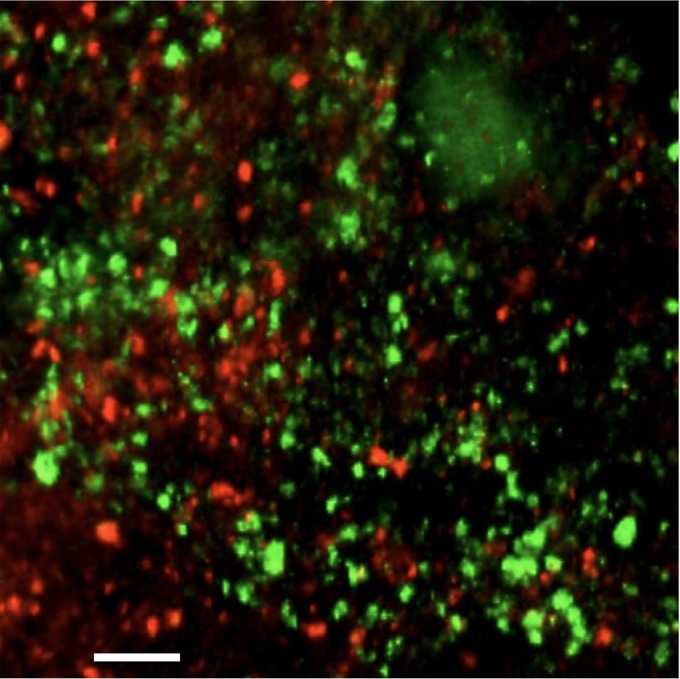

Marvin Whiteley (University of Texas, Austin, TX) discussed the importance of spatial organization and the use of methods to reproduce the structural biofilm integrity in laboratory settings. Using S. aureus-P. aeruginosa and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans-Streptococcus gordonii interactions as examples, Dr. Whiteley showed that there is an optimal distance at which cells can grow adjacent to each other in an infection site (50). This underlines the importance of spatial positioning in polymicrobial infections and suggests that targeting biogeography and spatial location could constitute a valid therapeutic strategy (Fig. 4) (51).

FIG 4.

Confocal micrograph of a skin abscess coinfected with A. actinomycetemcomitans (red) and S. gordonii (green). Shown is a confocal micrograph of a 3-day-old murine skin abscess coinfected with the oral cavity pathogen Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (red) and the oral cavity commensal Streptococcus gordonii (green). Spatial analysis of abscesses revealed that A. actinomycetemcomitans and S. gordonii persist in vivo as biofilm-like aggregates that are about 0.5 pl in volume and that A. actinomycetemcomitans maintains a >4-μm distance away from S. gordonii. Mutation of the enzyme dispersin B in A. actinomycetemcomitans, which degrades and allows it to disperse from biofilms, disrupts the ability of A. actinomycetemcomitans to achieve its optimal spacing from S. gordonii and as a result mitigates its virulence in the abscess. Scale bar, 25 μm. (Courtesy of Jake Everett and Kendra Rumbaugh, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center; reproduced with permission.)

John Kirby (University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA) similarly discussed spatial aspects of bacterium-bacterium interactions in his work investigating predator-prey dynamics within a biofilm. Dr. Kirby described how unknown metabolites, including myxoprincomide produced by Myxococcus xanthus, induce the formation of novel megastructures by B. subtilis that are raised above the surface and filled with viable endospores embedded within a dense matrix. Genetically distinguishable from colony biofilm formation, megastructures provide a mechanism for survival of B. subtilis against predation, permitting them to escape into dormancy via sporulation. Bacillus subtilis also produces the metabolite bacillaene to fend off predatory M. xanthus. Antibiotic production at the interface between layers of M. xanthus and B. subtilis spores may result in a “standoff” between the two organisms (52).

Interactions between more than two partners were also explored. Mette Burmølle (University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark) presented her work on interactions within a mixed biofilm comprising four bacterial soil isolates. Dr. Burmølle observed that all four strains benefitted from joining the multispecies biofilm, which is strongly indicative of cooperative forces that shape multispecies biofilm communities (53). Staffan Kjelleberg (SCELSE, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, and Centre for Marine BioInnovation, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia) discussed how defined, simple multispecies biofilms as well as highly species-rich wastewater biofilm granules can be experimentally designed to explore biofilm community traits and ecological theories (54). Dr. Kjelleberg described how increased species richness replaces intraspecific variants to offer community rather than population stress protection and how quorum-sensing signaling is a true community trait with signal production and quenching assigned to phylogenetically different organisms. These approaches suggest that complex microbial biofilms can be designed to understand biofilm biology also at the community level, reflecting natural biofilm systems (55).

The host environment provides additional factors that may influence microbial interactions. Catherine R. Armbruster (University of Washington, Seattle, WA) showed that the S. aureus extracellular virulence factor SpA plays a previously undescribed role in polymicrobial interactions within biofilms. SpA influences the course of P. aeruginosa infection by binding type IV pili and the exopolysaccharide Psl, leading to inhibition of not only biofilm formation but also phagocytosis by neutrophils. Because S. aureus frequently precedes P. aeruginosa in chronic infections, Dr. Armbruster proposed that SpA can impact P. aeruginosa persistence and host interactions during coinfection (64). These results provide an indication of the complex and potentially unexpected interactions that occur in polymicrobial infections via secreted extracellular virulence factors with multiple functions. Katharina Ribbeck (MIT, Cambridge, MA) discussed the role of mucins, gel-forming components secreted by goblet cells, in interactions between different microbes. Dr. Ribbeck described how mucin can reduce bacterial adhesion by blocking attachment, promoting dispersion, or affecting interspecies communication and suppression of virulence factors (56).

CONCLUSIONS

The biofilm field is rapidly growing, and the 7th ASM biofilm conference provided a platform for researchers from different scientific disciplines to discuss and exchange ideas in all aspects of biofilm research, including fundamentals of biofilm formation and biofilm control and encompassing biofilms in medicine, in the natural environment, and in industry. In search of answers to fundamental scientific questions regarding the molecular underpinnings of surface attachment, production and composition of the biofilm matrix, physiological consequences of biofilm formation, and regulation of biofilm formation, biofilm researchers are using interdisciplinary approaches leading to unprecedented molecular detail. For example, the use of electrochemical camera chips or MALDI-TOF imaging mass spectrometry for simultaneous imaging of multiple metabolites in biofilms is leading to a better understanding of the biochemical processes that occur during biofilm development and in biofilms formed in the natural environment. Application of noninvasive imaging methods in living biofilms at high spatial and temporal resolution combined with big data analysis is revealing fundamental principles of biofilm formation. It was exciting to see translational work capitalizing on the advancement of our understanding of biofilm formation. The increasing focus on translational work was revealed through a plethora of examples, including the use of antibodies and engineered enzymes to target biofilm matrix components, novel biomaterials engineered to prevent adherence of biofilm bacteria, and compounds designed to target major structures and regulatory circuits to control biofilm formation. Finally, the importance of understanding mechanisms of multispecies biofilm formation, the diversity and functions of microbes in the community in which they live, and the necessity for the development of techniques to answer these questions were highlighted. The objectives of this meeting were to bring together scientists from across the world to present and discuss the best and most up-to-date research on biofilms, to better understand and control biofilms, and to foster interdisciplinary collaborations.

During the closing remarks, Jean-Marc Ghigo announced that the next and 8th edition of the ASM biofilm conference would be held in 2018 and encouraged biofilm lovers to disperse and recruit new talent to the biofilm field.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Fitnat Yildiz (chair) and Jean-Marc Ghigo (cochair) gratefully acknowledge Paul Stoodley, Thomas Bjarnsholt, Claus Moser, Darla Goeres, Alex Rickhardt, and all their colleagues for their dedication and involvement in the organization of the workshops. They also thank the conference program committee members Clay Fuqua, Tom Battin, Susanne Haussler, George O'Toole, Phil Stewart, Mark Schembri, and Pradeep Singh for their contributions.

We thank the following sponsors for their support of the 7th ASM Conference on Biofilms: Burroughs Welcome Fund (Platinum supporter); Biofilm Control, Bitplane, Center for Biofilm Engineering at MSU, EMD Millipore, Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, Recombina, Thorlabs, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals (Gold supporters); Leica Microsystems and Sharklet Technologies (Silver supporters); and Biosurface Technologies and Cook Medical (Bronze supporters).

REFERENCES

- 1.Kopf SH, Sessions AL, Cowley ES, Reyes C, Van Sambeek L, Hu Y, Orphan VJ, Kato R, Newman DK. 2016. Trace incorporation of heavy water reveals slow and heterogeneous pathogen growth rates in cystic fibrosis sputum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:E110–E116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1512057112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babin BM, Bergkessel M, Sweredoski MJ, Moradian A, Hess S, Newman DK, Tirrell DA. 2016. SutA is a bacterial transcription factor expressed during slow growth in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:E597–E605. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514412113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yawata Y, Cordero OX, Menolascina F, Hehemann JH, Polz MF, Stocker R. 2014. Competition-dispersal tradeoff ecologically differentiates recently speciated marine bacterioplankton populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:5622–5627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318943111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan J, Hammond JH, Hogan DA, Greene CS. 2016. ADAGE-based integration of publicly available Pseudomonas aeruginosa gene expression data with denoising autoencoders illuminates microbe-host interactions. mSystems 1(1):e00025-15. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00025-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen AI, Dolben EF, Okegbe C, Harty CE, Golub Y, Thao S, Ha DG, Willger SD, O'Toole GA, Harwood CS, Dietrich LE, Hogan DA. 2014. Candida albicans ethanol stimulates Pseudomonas aeruginosa WspR-controlled biofilm formation as part of a cyclic relationship involving phenazines. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004480. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brooks JF II, Gyllborg MC, Cronin DC, Quillin SJ, Mallama CA, Foxall R, Whistler C, Goodman AL, Mandel MJ. 2014. Global discovery of colonization determinants in the squid symbiont Vibrio fischeri. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:17284–17289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415957111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feirer N, Xu J, Allen KD, Koestler BJ, Bruger EL, Waters CM, White RH, Fuqua C. 2015. A pterin-dependent signaling pathway regulates a dual-function diguanylate cyclase-phosphodiesterase controlling surface attachment in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. mBio 6:e00156. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00156-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mukherjee S, Bree AC, Liu J, Patrick JE, Chien P, Kearns DB. 2015. Adaptor-mediated Lon proteolysis restricts Bacillus subtilis hyperflagellation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:250–255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417419112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luo Y, Zhao K, Baker AE, Kuchma SL, Coggan KA, Wolfgang MC, Wong GC, O'Toole GA. 2015. A hierarchical cascade of second messengers regulates Pseudomonas aeruginosa surface behaviors. mBio 6:e02456-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02456-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laventie BJ, Nesper J, Ahrne E, Glatter T, Schmidt A, Jenal U. 2015. Capture compound mass spectrometry—a powerful tool to identify novel c-di-GMP effector proteins. J Vis Exp doi: 10.3791/51404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fiebig A, Herrou J, Fumeaux C, Radhakrishnan SK, Viollier PH, Crosson S. 2014. A cell cycle and nutritional checkpoint controlling bacterial surface adhesion. PLoS Genet 10:e1004101. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orell A, Peeters E, Vassen V, Jachlewski S, Schalles S, Siebers B, Albers SV. 2013. Lrs14 transcriptional regulators influence biofilm formation and cell motility of Crenarchaea. ISME J 7:1886–1898. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones CJ, Utada A, Davis KR, Thongsomboon W, Zamorano Sanchez D, Banakar V, Cegelski L, Wong GC, Yildiz FH. 2015. C-di-GMP regulates motile to sessile transition by modulating MshA pili biogenesis and near-surface motility behavior in Vibrio cholerae. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005068. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Floyd KA, Moore JL, Eberly AR, Good JA, Shaffer CL, Zaver H, Almqvist F, Skaar EP, Caprioli RM, Hadjifrangiskou M. 2015. Adhesive fiber stratification in uropathogenic Escherichia coli biofilms unveils oxygen-mediated control of type 1 pili. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004697. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Formosa-Dague C, Speziale P, Foster TJ, Geoghegan JA, Dufrene YF. 2016. Zinc-dependent mechanical properties of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm-forming surface protein SasG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:410–415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1519265113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jennings LK, Storek KM, Ledvina HE, Coulon C, Marmont LS, Sadovskaya I, Secor PR, Tseng BS, Scian M, Filloux A, Wozniak DJ, Howell PL, Parsek MR. 2015. Pel is a cationic exopolysaccharide that cross-links extracellular DNA in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:11353–11358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503058112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bromley KM, Morris RJ, Hobley L, Brandani G, Gillespie RM, McCluskey M, Zachariae U, Marenduzzo D, Stanley-Wall NR, MacPhee CE. 2015. Interfacial self-assembly of a bacterial hydrophobin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:5419–5424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419016112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park JH, Jo Y, Jang SY, Kwon H, Irie Y, Parsek MR, Kim MH, Choi SH. 2015. The cabABC operon essential for biofilm and rugose colony development in Vibrio vulnificus. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005192. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desai JV, Mitchell AP. 2015. Candida albicans biofilm development and its genetic control. Microbiol Spectr 3. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.MB-0005-2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li G, Brown PJ, Tang JX, Xu J, Quardokus EM, Fuqua C, Brun YV. 2012. Surface contact stimulates the just-in-time deployment of bacterial adhesins. Mol Microbiol 83:41–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07909.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schumacher MA, Balani P, Min J, Chinnam NB, Hansen S, Vulic M, Lewis K, Brennan RG. 2015. HipBA-promoter structures reveal the basis of heritable multidrug tolerance. Nature 524:59–64. doi: 10.1038/nature14662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta K, Liao J, Petrova OE, Cherny KE, Sauer K. 2014. Elevated levels of the second messenger c-di-GMP contribute to antimicrobial resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 92:488–506. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de la Fuente-Nunez C, Reffuveille F, Mansour SC, Reckseidler-Zenteno SL, Hernandez D, Brackman G, Coenye T, Hancock RE. 2015. D-enantiomeric peptides that eradicate wild-type and multidrug-resistant biofilms and protect against lethal Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Chem Biol 22:196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen UT, Harvey H, Hogan AJ, Afonso AC, Wright GD, Burrows LL. 2014. Role of PBPD1 in stimulation of Listeria monocytogenes biofilm formation by subminimal inhibitory beta-lactam concentrations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:6508–6517. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03671-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pasquina L, Santa Maria JP Jr, McKay Wood B, Moussa SH, Matano LM, Santiago M, Martin SE, Lee W, Meredith TC, Walker S. 2016. A synthetic lethal approach for compound and target identification in Staphylococcus aureus. Nat Chem Biol 12:40–45. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steenackers H, Ermolat'ev D, Trang TT, Savalia B, Sharma UK, De Weerdt A, Shah A, Vanderleyden J, Van der Eycken EV. 2014. Microwave-assisted one-pot synthesis and anti-biofilm activity of 2-amino-1H-imidazole/triazole conjugates. Org Biomol Chem 12:3671–3678. doi: 10.1039/c3ob42282h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolderman E, Bettampadi D, Samarian D, Dowd SE, Foxman B, Jakubovics NS, Rickard AH. 2015. l-arginine destabilizes oral multi-species biofilm communities developed in human saliva. PLoS One 10:e0121835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonzalez-Escobedo G, Marshall JM, Gunn JS. 2011. Chronic and acute infection of the gall bladder by Salmonella Typhi: understanding the carrier state. Nat Rev Microbiol 9:9–14. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andersson EK, Bengtsson C, Evans ML, Chorell E, Sellstedt M, Lindgren AE, Hufnagel DA, Bhattacharya M, Tessier PM, Wittung-Stafshede P, Almqvist F, Chapman MR. 2013. Modulation of curli assembly and pellicle biofilm formation by chemical and protein chaperones. Chem Biol 20:1245–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gallo PM, Rapsinski GJ, Wilson RP, Oppong GO, Sriram U, Goulian M, Buttaro B, Caricchio R, Gallucci S, Tukel C. 2015. Amyloid-DNA composites of bacterial biofilms stimulate autoimmunity. Immunity 42:1171–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bellin DL, Sakhtah H, Zhang Y, Price-Whelan A, Dietrich LE, Shepard KL. 2016. Electrochemical camera chip for simultaneous imaging of multiple metabolites in biofilms. Nat Commun 7:10535. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bleich R, Watrous JD, Dorrestein PC, Bowers AA, Shank EA. 2015. Thiopeptide antibiotics stimulate biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:3086–3091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414272112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Powers MJ, Sanabria-Valentin E, Bowers AA, Shank EA. 2015. Inhibition of cell differentiation in Bacillus subtilis by Pseudomonas protegens. J Bacteriol 197:2129–2138. doi: 10.1128/JB.02535-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baig NF, Dunham SJ, Morales-Soto N, Shrout JD, Sweedler JV, Bohn PW. 2015. Multimodal chemical imaging of molecular messengers in emerging Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacterial communities. Analyst 140:6544–6552. doi: 10.1039/C5AN01149C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cegelski L. 2015. Bottom-up and top-down solid-state NMR approaches for bacterial biofilm matrix composition. J Magn Reson 253:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2015.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blauert F, Horn H, Wagner M. 2015. Time-resolved biofilm deformation measurements using optical coherence tomography. Biotechnol Bioeng 112:1893–1905. doi: 10.1002/bit.25590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun D, Cheng S, Wang A, Li F, Logan BE, Cen K. 2015. Temporal-spatial changes in viabilities and electrochemical properties of anode biofilms. Environ Sci Technol 49:5227–5235. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b00175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Persat A, Nadell CD, Kim MK, Ingremeau F, Siryaporn A, Drescher K, Wingreen NS, Bassler BL, Gitai Z, Stone HA. 2015. The mechanical world of bacteria. Cell 161:988–997. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.May RM, Magin CM, Mann EE, Drinker MC, Fraser JC, Siedlecki CA, Brennan AB, Reddy ST. 2015. An engineered micropattern to reduce bacterial colonization, platelet adhesion and fibrin sheath formation for improved biocompatibility of central venous catheters. Clin Transl Med 4:9. doi: 10.1186/s40169-015-0050-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Howell C, Vu TL, Lin JJ, Kolle S, Juthani N, Watson E, Weaver JC, Alvarenga J, Aizenberg J. 2014. Self-replenishing vascularized fouling-release surfaces. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 6:13299–13307. doi: 10.1021/am503150y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu J, Prindle A, Humphries J, Gabalda-Sagarra M, Asally M, Lee DY, Ly S, Garcia-Ojalvo J, Suel GM. 2015. Metabolic co-dependence gives rise to collective oscillations within biofilms. Nature 523:550–554. doi: 10.1038/nature14660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prindle A, Liu J, Asally M, Ly S, Garcia-Ojalvo J, Suel GM. 2015. Ion channels enable electrical communication in bacterial communities. Nature 527:59–63. doi: 10.1038/nature15709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O'Rourke D, FitzGerald CE, Traverse CC, Cooper VS. 2015. There and back again: consequences of biofilm specialization under selection for dispersal. Front Genet 6:18. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2015.00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ellis CN, Traverse CC, Mayo-Smith L, Buskirk SW, Cooper VS. 2015. Character displacement and the evolution of niche complementarity in a model biofilm community. Evolution 69:283–293. doi: 10.1111/evo.12581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koch G, Yepes A, Forstner KU, Wermser C, Stengel ST, Modamio J, Ohlsen K, Foster KR, Lopez D. 2014. Evolution of resistance to a last-resort antibiotic in Staphylococcus aureus via bacterial competition. Cell 158:1060–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Gestel J, Weissing FJ, Kuipers OP, Kovacs AT. 2014. Density of founder cells affects spatial pattern formation and cooperation in Bacillus subtilis biofilms. ISME J 8:2069–2079. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dahlstrom KM, Giglio KM, Collins AJ, Sondermann H, O'Toole GA. 2015. Contribution of physical interactions to signaling specificity between a diguanylate cyclase and its effector. mBio 6:e01978-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01978-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Whitney JC, Quentin D, Sawai S, LeRoux M, Harding BN, Ledvina HE, Tran BQ, Robinson H, Goo YA, Goodlett DR, Raunser S, Mougous JD. 2015. An interbacterial NAD(P)(+) glycohydrolase toxin requires elongation factor Tu for delivery to target cells. Cell 163:607–619. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anderson MS, Garcia EC, Cotter PA. 2014. Kind discrimination and competitive exclusion mediated by contact-dependent growth inhibition systems shape biofilm community structure. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004076. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stacy A, Everett J, Jorth P, Trivedi U, Rumbaugh KP, Whiteley M. 2014. Bacterial fight-and-flight responses enhance virulence in a polymicrobial infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:7819–7824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400586111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stacy A, McNally L, Darch SE, Brown SP, Whiteley M. 2016. The biogeography of polymicrobial infection. Nat Rev Microbiol 14:93–105. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2015.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muller S, Strack SN, Ryan SE, Kearns DB, Kirby JR. 2015. Predation by Myxococcus xanthus induces Bacillus subtilis to form spore-filled megastructures. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:203–210. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02448-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ren D, Madsen JS, Sorensen SJ, Burmolle M. 2015. High prevalence of biofilm synergy among bacterial soil isolates in cocultures indicates bacterial interspecific cooperation. ISME J 9:81–89. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kelvin Lee KW, Hoong Yam JK, Mukherjee M, Periasamy S, Steinberg PD, Kjelleberg S, Rice SA. 2015. Interspecific diversity reduces and functionally substitutes for intraspecific variation in biofilm communities. ISME J doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tan CH, Koh KS, Xie C, Zhang J, Tan XH, Lee GP, Zhou Y, Ng WJ, Rice SA, Kjelleberg S. 2015. Community quorum sensing signalling and quenching: microbial granular biofilm assembly. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 1:15006. doi: 10.1038/npjbiofilms.2015.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frenkel ES, Ribbeck K. 2015. Salivary mucins protect surfaces from colonization by cariogenic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:332–338. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02573-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cairns LS, Hobley L, Stanley-Wall NR. 2014. Biofilm formation by Bacillus subtilis: new insights into regulatory strategies and assembly mechanisms. Mol Microbiol 93:587–598. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jiang C, Brown PJ, Ducret A, Brun YV. 2014. Sequential evolution of bacterial morphology by co-option of a developmental regulator. Nature 506:489–493. doi: 10.1038/nature12900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Taglialegna A, Navarro S, Ventura S, Garnett JA, Matthews S, Penades JR, Lasa I, Valle J. 2016. Staphylococcal Bap proteins build amyloid scaffold biofilm matrices in response to environmental signals. PLoS Pathog. 12:e1005711. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Allan RN, Morgan S, Brito-Mutunayagam S, Skipp P, Feelisch M, Hayes SM, Hellier W, Clarke SC, Stoodley P, Burgess A, Ismail-Koch H, Salib RJ, Webb JS, Faust SN, Hall-Stoodley L. 2016. Low concentrations of nitric oxide modulate Streptococcus pneumoniae biofilm metabolism and antibiotic tolerance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:2456–2466. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02432-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baker P, Hill PJ, Snarr BD, Alnabelseya N, Pestrak MJ, Lee MJ, Jennings LK, Tam J, Melnyk RA, Parsek MR, Sheppard DC, Wozniak DJ, Howell PL. 2016. Exopolysaccharide biosynthetic glycoside hydrolases can be utilized to disrupt and prevent Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Sci Adv 2:e1501632. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hathroubi S, Beaudry F, Provost C, Martelet L, Segura M, Gagnon CA, Jacques M. 2016. Impact of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae biofilm mode of growth on the lipid A structures and stimulation of immune cells. Innate Immun 22:353–362. doi: 10.1177/1753425916649676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Garcia EC, Perault AI, Marlatt SA, Cotter PA. 2016. Interbacterial signaling via Burkholderia contact-dependent growth inhibition system proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:8296–8301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606323113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Armbruster CR, Wolter DJ, Mishra M, Hayden HS, Radey MC, Merrihew G, MacCoss MJ, Burns J, Wozniak DJ, Parsek MR, Hoffman LR. 2016. Staphylococcus aureus protein A mediates interspecies interactions at the cell surface of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. mBio 7(3):e00538-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00538-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ducret A, Quardokus EM, Brun YV. 2016. MicrobeJ, a tool for high throughput bacterial cell detection and quantitative analysis. Nat Microbiol 1:16077. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]