Abstract

In this study we developed carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) microparticles through ionic crosslinking with the aqueous ion complex of zirconium (Zr) and further complexing with chitosan (CS) and determined the physio-chemical and biological properties of these novel microparticles. In order to assess the role of Zr, microparticles were prepared in 5% and 10% (w/v) zirconium tetrachloride solution. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS) results showed that Zr was uniformly distributed on the surface of the microparticles as a result of which uniform groovy surface was obtained. We found that Zr enhances the surface roughness of the microparticles and stability studies showed that it also increases the stability of microparticles in phosphate buffered saline. The crosslinking of anionic CMC with cationic Zr and CS was confirmed by fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) results. The response of murine pre-osteoblasts (OB-6) when cultured with microparticles was investigated. Live/dead cell assay showed that microparticles did not induce any cytotoxic effects as cells were attaching and proliferating on the well plate as well as along the surface of microparticles. In addition, SEM images showed that microparticles support the attachment of cells and they appeared to be directly interacting with the surface of microparticle. Within 10 days of culture most of the top surface of microparticles was covered with a layer of cells indicating that they were proliferating well throughout the surface of microparticles. We observed that Zr enhances the cell attachment and proliferation as more cells were present on microparticles with 10% Zr. These promising results show the potential applications of CMC-Zr microparticles in bone tissue engineering.

Keywords: Microparticles, Carboxymethyl cellulose, Zirconium, Surface Roughness, Pre-osteoblasts

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) is a hydrophilic biocompatible polymer obtained through the chemical modification of cellulose. It consists of carboxymethyl group attached to the polysaccharide backbone making it a polyelectrolyte. It has been identified as a smart cellulose material as its properties such as shape, mechanical rigidity and porosity can be altered in a controlled manner [1, 2].

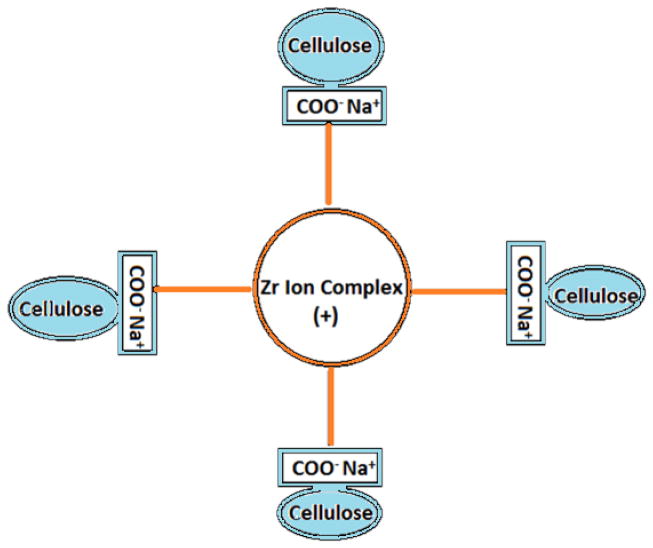

The presence of carboxymethyl group in CMC makes it soluble in water and negatively charged polymer. This enables it to undergo complexation with oppositely charged materials thereby forming a crosslinked matrix structure (Fig. 1) with improved physico-chemical and biological properties. CMC has been studied as an injectable gels, composites and films for potential bone regeneration applications [3–5]. In vivo study done with CMC showed that when used as a hybrid injectable material with calcium phosphate and bone morphogenetic protein can induce greater bone formation in rat tibial defect site [6].

Figure 1.

Ionic crosslinking interaction model for anionic CMC with cationic Zr ion complex

Injectable scaffolds have been extensively studied in bone tissue engineering in the recent years mainly because of their potential to minimize the surgical interventions. Scaffolds in the form of injectable gels offer advantages such as easy handling properties and adaptability to the defect site [7–9]. In order to make these injectable gels promising for bone tissue engineering, they should be able to incorporate drugs and bioactive agents and release them in a controlled manner. Studies have shown that growth factors incorporated directly into gels showed the large initial burst release [10, 11]. Particle (micro- and nano-) based injectable scaffolds can offer advantages in this aspect because of their ability to encapsulate the bioactive agents and release them in controlled manner. In addition, microparticle based scaffolds provide a temporary support for cells to attach and proliferate [12, 13].

For microparticles to be successfully used in bone regeneration, they need to be biocompatible, biodegradable and should enhance the osteoblast adhesion and proliferation without inducing any harmful effects to them [14, 15]. CMC beads prepared by crosslinking with multivalent metals have been used in many drug delivery applications which showed good encapsulation of drugs and pH sensitive release [16, 17]. These crosslinked 3-D CMC matrices are restricted to be used in bone tissue engineering applications due to the potential harmful effects of metal ions to osteoblasts [18, 19]. Zr is a tetravalent cationic metal with an interesting aqueous chemistry. In its aqueous solution, it rarely exists as a pure Zr4+ ion but rather undergoes complexation with hydroxide ion thereby forming complex cation among which Zr4(OH)48+ (Zr-ion) is the predominant one in low pH solution [20]. Zr has been extensively used in the development of prosthetic devices in the form of biologically inert zirconia due to their good mechanical properties and corrosion resistivity. It has also been used as an alloy with other metals as a bearing surface for bone implants because of its wear resistivity [21–23]. The occupational health guideline from center for disease control and prevention (CDC) has classified Zr as a metal with very low systemic toxicity and studies have shown that it has no adverse effects on osteoblasts [24]. It was recently found that Zr when added to cell culture medium with controlled concentration improves the differentiation and proliferation of human osteoblasts [25]. Due to its good mechanical properties and improved cell responses, Zr has also been incorporated into different scaffolds recently and has shown excellent biological response with osteoblasts and mesenchymal stem cells [26, 27].

After performing literature reviews, we found that although CMC has been extensively used as composites and injectable gel scaffolds for bone cells, the use of injectable microparticles has not been reported yet [3–5, 28–30]. In this study we aim to develop CMC microparticles that show a favorable biological response to osteoblasts and promote their adhesion and proliferation. These microparticles were fabricated by crosslinking anionic CMC with complex cationic species of Zr. The fabricated microparticles were further stabilized by introducing them to the cationic CS solution. In order to see the effects of Zr, microparticles were prepared with two different concentration of Zr and the effects on stability, surface structure, osteoblasts response were assessed. In order to study the drug release kinetics, we used cefazolin as a model drug which has been used in the treatment of bone diseases associated with the bacterial invasion [31].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Materials

Sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (average molecular weight 250,000 KDa, DS 0.7), zirconium (IV) chloride (ZrCl4) (≥99.5% trace metal basis), chitosan (medium molecular weight) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). Cefazolin sodium salt was purchased from MP Biomedicals (USA). Phosphate buffered saline (PBS), minimum essential media (MEM), penicillin/streptomycin and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were all purchased from Gibco (USA). LIVE/DEAD viability/Cytotoxicity kit was purchased from Invitrogen (USA).

2.2 Fabrication of microparticles

Microparticles were fabricated by crosslinking CMC with ionic species of zirconium present in hydrolyzed solution of ZrCl4. Aqueous solution of CMC (3% w/v) was prepared by slowly adding CMC into deionized (DI) water under stirring at room temperature. The viscous CMC solution thus obtained was then added dropwise into hydrolyzed solution of ZrCl4 through a syringe fitted with 30 gauge needle and left under stirring at 300 rpm for 3 h for crosslinking. Two different concentration of ZrCl4 was used (5% w/v-P1 and 10% w/v-P2) for the preparation of microparticles. The particles thus formed were washed with DI water to eliminate the ZrCl4 solution on their surface and were suspended in 2% CS solution for 24 h for complexation with CS. The particles looked more rigid and somewhat reduced in size after soaking in CS for 24 h. This might be due to the complexation of anionic CMC with cationic CS. They were again washed with DI water and were dried at room temperature for 48 h before further analysis.

2.3 Characterization of microparticles

-

SEM observation

The surface morphology of microparticles was analyzed using scanning electron microscope (SEM) (FEI quanta 3D FEG, FEI Company, USA) after sputter coating with gold for 30 s. Energy dispersive x-ray detector (EDS) with SEM was used to map the elemental Zr along the surface of microparticle and quantify the elements. Due to the spherical morphology of the microparticles it was only possible to collect the mapping results from top half of microparticle and bottom half was shaded.

-

IR spectroscopy

The intramolecular interaction between the components in microparticle was determined using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer (Excalibur Series FTIR, Varian). Dried samples were mixed with potassium bromide (KBr) and pressed into pellets using KBr kit. The pellets were loaded into the instrument and analyzed at a resolution of 8 cm−1, average 100 scans from 4000 to 400 cm−1.

-

X-ray diffraction (XRD) study

The phase analysis of zirconium present on microparticle was done with powder X-ray diffractometer (pXRD) (X’Pert Pro, PANalytical) with the crushed microparticles presented in powder form.

2.4 Stability of microparticles

The stability of microparticles was studied in PBS medium at pH 7.4. 10 mg of both microparticles (P1 and P2) were immersed in PBS at 37°C under continuous shaking at 25 rpm up to 35 days. PBS was changed every 24 h for first 2 days and every five days afterwards in order to mimic in vivo conditions. In order to monitor the hydrolysis of microparticles, pH of collected PBS was measured and the change in pH was plotted for 25 days. The microparticles after 35 days were imaged with SEM to see the integrity and intactness in PBS.

2.5 Osteoblast culture and live/dead cell assay

Murine osteoblast cells (OB-6) were cultured in α-MEM medium supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. To assess the in vitro cytotoxicity of microparticles, they were first soaked in culture medium for 24 h and UV sterilized for 30 mins. The microparticles settled at the bottom of the media were then transferred into 24-well plate for cell seeding. The cells were seeded at a density of 105 cells/ml to each well containing microparticles and without any microparticles (control). Medium was changed every 3 days and the cells were cultured up to 10 days for cytotoxicity assay. The viability of cells was indicated by the green fluorescence of calcein obtained by the enzymatic conversion of nonfluorescent cell-permeant acetomethoxy derivative of calcein and the dead cells were recognized simultaneously by the red fluorescence obtained by the binding of ethidium homodimer-1 to nucleic acids. The assay was performed on day 1, 3, 5, 7 and 10 according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The top surface of microparticle was imaged under fluorescence microscope (TIRF Microscope, Olympus) along with the bottom of well to determine the viable cells attached to the microparticle. ImageJ was used to determine the percent area of microparticles that was covered with cells on day 5 and 10.

2.6 Morphology and attachment of osteoblasts

The morphology of cells attached to the microparticles was determined using SEM. The microparticles were seeded with cells at 105 cells/ml in a 24-well plate and were imaged with SEM on day 5 and 10 after cell fixation. The cell fixation was done by immersing cell attached microparticles in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) at 4°C. They were then dehydrated in a series of ethanol (30%, 50%, 70%, 90%) three times each for 3 min and finally in 100% ethanol two times for 5 min each. Finally, microparticles were dried with 100% hexamethyldisilizane (HDMS) two times each for 5 mins before being imaged with SEM after gold coating for 20 sec.

2.7 Loading and release of cefazolin

Cefazolin was used as a model drug to study the release kinetics. Cefazolin was introduced to the microparticles in two different ways as encapsulation and coating. For encapsulation drug was added while preparing the CMC solution at the concentration of 2 mg/ml of polymer solution for both P1 and P2 while for coating fabricated particles were immersed in 8 mg/ml drug solution before drying and removed quickly before they start to disintegrate. In order to determine drug encapsulation efficiency, 20 mg of drug loaded microparticles were suspended in 3 ml 10X PBS for 48 h. Disintegrated microparticles were then sonicated for 20 mins, centrifuged and the supernatant was filtered through 0.45 micron filter before performing the quantitative measurement of entrapped drug in UV/Vis spectrophotometer (V-770, Jasco Analytical Instruments) at 270 nm. Encapsulation efficiency was calculated using following equation:

For drug coated microparticles all drug added to the microparticles was considered as total drug contained by the microparticles.

In vitro release of cefazolin from microparticles was assessed by incubating 20 mg of microparticles immersed in 2.5 ml 1X PBS (pH 7.4) at 37°C under shaking at 25 rpm. At predetermined time points PBS was collected and replaced with fresh PBS. The collected PBS was then filtered with 0.45 micron filter and the quantification of cefazolin in the collected PBS was done. The curves were plotted for both encapsulated and coated microparticles showing the percentage cumulative release of cefazolin at different time points.

2.8 Statistical analysis

Data from the quantitative analysis are obtained from triplicate samples and are presented as mean ± SD. The data analysis was done using SPSS one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Turkey’s Honest Significant Test to determine the statistical significance among the study groups. A probability value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1 SEM-EDS and XRD study

The size of microparticles ranged from 700 to 750 μm for both P1and P2. SEM images showed that the microparticles were spherical in shape and their surface consisted of grooves and ridges that created a rough surface. Hairline cracks in a concentric pattern were also observed along the surface of both P1 and P2 which that made the surface rougher without interfering with integrity and intactness of microparticles. The distribution of cracks along the surface was similar for both P1 and P2. The surface of P2 looked more fibrillar and groovier whereas the surface of P1 looked more granular and less groovier due to which surface of P2 was rougher than that of P1 (Fig. 2). This indicates that the increase in Zr concentration increases the surface irregularities thereby creating a rougher surface.

Figure 2.

SEM image of P1 (a) and P2 (b) show spherical morphology of microparticle at low magnification. The rough surface of P1 (c) and P2 (d) can be seen at higher magnification.

SEM-EDS elemental mapping was done to analyze the distribution of Zr on the microparticles. The elements distributed along the surface of microparticles is shown in figure 3A with Zr indicated by green, carbon by yellow and oxygen by red. The figure shows that Zr was well distributed along the surface of the microparticles. The distribution of Zr along the surface of P2 looked denser than that along the surface of P1.

Figure 3.

Figure 3A. EDS elemental mapping of P1 (a-SEM image of microparticle, b-carbon, c-oxygen, d-zirconium) and P2 (A-SEM image of microparticle, B-carbon, C-oxygen, D-zirconium).

Fig 3B: EDS spectra of P1 and P2 showing their elemental composition. Spectra on the right shows the intensity of Zr along the surface of P1 and P2.

The representative spectra collected along the different regions on the surface of P1 and P2 is shown in the figure 3B. As shown in the figure on the right the intensity of Zr from P2 was slightly higher than that from P1. The quantitative data showed an average of 24 wt.% Zr along P1 compared to 28 wt.% in P2.

XRD spectrum was collected to determine if any oxide derivative of zirconium, zirconia, is present on the microparticles. Zirconia is crystalline in nature and shows sharp diffraction peaks. The XRD pattern of microparticle is shown on figure 4. Both P1 and P2 showed broad peaks from the polymer and lacked any sharp diffraction peaks. This suggested that the Zr present in the microparticles was in amorphous form.

Figure 4.

XRD spectrum of microparticle showing amorphous state of Zr and CMC.

3.2 FTIR analysis

In its aqueous solution, Zr compounds undergo hydrolysis forming oligomeric ion complex (Zr)4(OH)48+ along with Zr4+ ions that are negligibly present in their solution [20]. In order to study the presence of these ion and their interaction with CMC, FTIR analysis was done. The IR spectrum (Fig. 5) of CMC showed a broad peak at 3445 cm−1 which is due to the stretching vibration of O-H bond and a peak at 2909 cm−1 is due to the stretching of C-H bond. The bands appearing at 1616 cm−1 and 1420 cm−1 represents the asymmetrical and symmetrical vibration of COO− group. The peak at 1616 cm−1 in CMC was shifted to 1593 cm−1 in microparticle suggesting the interaction between the cationic species (Zr-ion and NH3+ in CS) with anionic species (COO−) in CMC. The appearance of peak at 460 cm−1 in microparticle indicated the presence of Zr-O vibration [32] suggesting the presence of (Zr)4(OH)48+ ion complex.

Figure 5.

FTIR spectra of pure CMC and microparticles.

3.3 Stability study

The stability of microparticles depends on their hydrolytic degradation behavior. The hydrolytic degradation behavior of microparticles was determined by monitoring the pH change of PBS induced by the degradation of microparticles. The data showed that there was not much alterations in pH of PBS over 30 day study period except for the first day when PBS turned slightly acidic (Fig. 6). This could be due to the release of residual acetic acid carried from the CS coated into the surface of microparticles. SEM images of degraded microparticles after 35 days of immersion in PBS (pH 7.4) is shown in figure 7. P1 lost their structural integrity and were disrupted whereas P2 maintained their physical integrity in PBS within study period although the shape was distorted. As seen in SEM images, the disintegration of P1 was not into multiple fragments but into two hemispheres thereby exposing the inner macro-porous polymer core. This could be due to the disintegration of microparticles along the concentric cracks observed on the surface of microparticles until they finally break down into hemispherical fragments. The higher crosslinking density in P2 prevented the early disintegration.

Figure 6.

Variation in pH of PBS (pH 7.4) containing microparticles over 25 days (n=3). Stable neutral pH was maintained by both P1 and P2.

Figure 7.

SEM images showing the stability of microparticles after 35 days of immersion in PBS (pH 7.4). The stability of P1 (a & b) was lower compared to P2 (c & d).

3.4 Live/Dead cell assay

The fluorescence images showing the viability of cells attached to the bottom of 24-well plate observed on day 10 is shown in figure 8A. The cells in the wells containing microparticles grew and proliferated well on the well plate indicated by green fluorescence although few dead cells indicated by red fluorescence were also observed. This was similar to control where few dead cells were observed which could be due to over-proliferation of cells. Both microparticles P1 and P2 induced very low to no cytotoxicity to osteoblasts which implies increasing Zr concentration as a cross-linker is not detrimental to osteoblasts. The viable cells attached to the surface of P1 and P2 on day 5 and day 10 is shown in figure 8B. The cells proliferated along the surface of both P1 and P2 and were growing in a number of colonies along their surface on day 10. A significant difference was observed on percentage area covered with cells between P1 and P2 on day 10 (p<0.05) which was determined using ImageJ. About 20% of top surface area of P2 was covered with cells compared to about 6% in P1. A significant difference was also observed on percentage area of P2 covered with cells between day 5 and 10 (p<0.05). This indicated that the cells were growing and proliferating better along the surface of P2 and Zr was providing favorable surface for cells to attach and proliferate.

Figure 8.

Figure 8A. Cells proliferating at the bottom of the wells without microparticles (a) with P1 (b) and with P2 (c) on day 10. Green fluorescence represents live and red dots represent dead cells (scale 100 μm).

Figure 8B. Viable Cells (bright green spots) attached and proliferating on the surface of P1 on day 5 (a) and 10 (b) and on the surface of P2 on day 5 (c) and 10 (d).

Figure 8C. Microparticles surface area covered with cells.

3.5 Morphology study by SEM

On day 5 and 10, osteoblasts appeared to be attaching and proliferating along the surface of both P1 and P2. SEM images showed that the cells proliferated in a number of small colonies on day 5 while on day 10 they formed big colonies almost covering one third surface of microparticle (Fig. 9A and 9B). The surface of P2 contained more number and dense cell colonies than P1 on day 5 while on day 10 not much difference was observed. Most of the cells on day 5 were spherical in shape clearly visible as extending above the surface while on day 10 they were more flattened visible as forming a thin layer along the surface of microparticles. The cells were adhering with good extension and anchorage into the surface of the microparticles. The increase in Zr content in microparticles enhanced the adhesion and proliferation of osteoblasts into microparticle as they grew in larger colonies and covered more surface of P2 than P1. Cells were also growing along the small cracks on the surface of microparticles (Fig 9C) indicating those cracks were not interfering the biological properties of microparticle.

Figure 9.

Figure 9A. SEM images of cells attached to P1 on day 5 (a & b) and on day 10 (c & d).

Figure 9B. SEM images of cells attached to P2 on day 5 (a & b) and day 10 (c & d).

Figure 9C. SEM images of cells proliferating along the cracks in P1 (a) and P2 (b) on day 10.

3.6 Cefazolin release study

Cefazolin, an antibiotic, was used as a model drug to assess the release kinetics of fabricated microparticles. Both P1 and P2 showed low encapsulation efficiency for cefazolin with P1 encapsulating 20% and P2 encapsulating 18% of drug. The low encapsulation efficiency of P2 is expected due to higher density of cross-links. The low incorporation of drug into microparticles could be due to the similar chemical nature of cefazolin and CMC (negatively charged) and loss of drug during long fabrication process of microparticles. The cumulative drug release in PBS is shown in figure 10A. Both P1 and P2 showed similar release kinetics with initial burst release followed by slow release. Both of them released nearly 20% of drug by day 1, however, the release by P2 after day 1 slowed down compared to P1. By the end of day 27, P2 released only 35% of encapsulated drug whereas P1 released more than 50% of encapsulated drug. The initial burst release can be attributed to the release of drug present on the surface of microparticles. The disintegration of P1 might have led to faster and higher release from it compared to P2.

Figure 10.

Figure 10A. Percent cumulative drug released from drug encapsulated P1 and P2.

Figure 10B. Percent cumulative drug released from drug coated P1 and P2.

The drug coated microparticles released absorbed drug relatively much faster than encapsulated microparticles. As shown in figure 10B, almost 98% and more than 85% of drug absorbed by P1 and P2 respectively was released by day 10. Two different method of introducing the drug here shows that the fabricated microparticles have the ability to encapsulate the drug and release them in sustained manner.

4. Discussion

CMC crosslinked with different multivalent metal has been used in drug delivery applications. Trivalent metal ions such aluminum (Al), iron (Fe) has been used to fabricate CMC beads for drug delivery applications. However, the toxic effect to osteoblasts associated with these metal ions has limited the use of metal-crosslinked 3D CMC matrices in bone regeneration [18, 19]. In addition to directly inhibiting the cell growth and proliferation, it has been shown that these metal ions also impair the bone mineralization process ultimately leading to osteomalacia in in vivo conditions [33]. Zr has been studied to cause no any adverse effects on the growth and proliferation of osteoblasts. It has been shown that incorporation of Zr into scaffolds or the coating of Zr into implant surface has resulted in higher proliferation of osteoblasts and greater expression of alkaline phosphate (ALP), bone sialoprotein and collagen type I compared to the samples without Zr [26, 27, 34]. In this study we developed CMC microparticles based on Zr ion complex as a cross-linker. Before starting our studies with Zr, we studied the biological response of aluminum (Al) crosslinked CMC spherical scaffolds. However, we found these scaffolds were highly toxic to the osteoblasts indicated by the in vitro cytotoxicity assay and the results were not included here. Zr-crosslinked CMC microparticles showed very low to no toxicity to osteoblasts and provided an excellent surface for their adhesion and proliferation. The microparticles to be used in bone regeneration should have a good adhesion surface and should promote its proliferation on the surface [15]. The homogenous distribution of Zr along the microparticle enabled us to get a rough surface with patterned grooves and ridges that promoted the adhesion and proliferation of osteoblasts. Zr has been studied to stimulate the osteogenic properties of human osteoblasts [25] and this property can be effectively combined into a 3D scaffold in the form Zr crosslinked CMC microparticles. Our results showed that increasing the Zr concentration while fabricating microparticles was not detrimental to osteoblasts instead promoted their adhesion and proliferation.

The fabrication of microparticles takes nearly 48 h as the particles obtained after ionic crosslinking in Zr solution are further transferred to CS solution for their stabilization through the interaction between amine group in CS and free carboxyl groups on CMC particles [35, 36]. This interaction of carboxyl groups of CMC with positive ions was confirmed by the FTIR results. Zr in its aqueous solution is predominantly present as a hydration ion complex (Zr)4(OH)48+ rather than a pure Zr4+ ion [20]. The presence of Zr-O vibration in FTIR spectrum of microparticle indicated that microparticles were obtained due to the crosslinks created by the hydrated cationic complex of Zr in CMC.

The stability of microparticles is important to support the seeded cells and allow them to attach and proliferate. It is also important for the controlled release of the encapsulated drugs or bioactive agents [37]. It was observed that Zr increased the stability of microparticles in neutral pH as P2 were intact and stable up to 35 days of immersion in PBS compared to P1 which were disintegrated and starting to degrade within the same study period. This is associated with the lower degree of crosslinking in P1 as a result of which crosslinking Zr ions are quickly replaced by univalent potassium and sodium ions in PBS and hence breaking the crosslinks whereas in P2 the higher degree of crosslinking enables slower replacement of ions [38]. Swelling was observed in P1 before they started to lose their stability which could be again associated with the lower degree of crosslinking enabling more water molecules to enter into polymer matrix.

Good biocompatibility of the microparticles is needed which is often assessed by the in vitro cell responses. Microparticles intended for bone tissue engineering shouldn’t induce any cytotoxicity and should provide a good surface for the attachment and proliferation of osteoblasts. Our live/dead cell assay result shows that both P1 and P2 were not toxic to the osteoblasts as they were growing and proliferating on the bottom of well containing microparticles and was comparable to the control without microparticles. This might be associated with the low toxicity of Zr as well as the aqueous property of Zr. In its aqueous solution, Zr does not exist as a Zr4+ ion but rather as a complex hydroxide ion and many studies have shown that oxide derivatives of Zr and other metals are not toxic to osteoblasts [20, 39, 40]. The attachment of viable cells to the surface of both P1 and P2 further shows that the microparticles were not cytotoxic. In addition, significantly higher cell attachment to P2 compared to P1 on day 10 indicates that Zr improved the proliferation of cells into the microparticles.

Surface roughness is one of the important features that influences the cell behavior during the adhesion and proliferation stage before cells establish their own environment. Zr has been used in many biomedical implants in the form of zirconia because of their better mechanical properties, chemical inertness and bone bonding abilities [41, 42]. In our study both P1 and P2 showed the uniform distribution of Zr along their surface seen through EDS mapping data as a result of which patterned and uniform rough surface was observed all along the microparticle. The uniformity in surface roughness is another important factor that determines cell attachment. The cells like to adhere and proliferate more on ordered and uniform rough surface compared to surface where roughness is created by random patterns and discontinuation [43]. The surface of P2 looked groovier and rougher than P1 (Fig 2) suggesting that Zr improves the surface roughness of the microparticles. The micro-cracks observed along the surface was found not to be interfering with the intactness and stability of the microparticles as well as the attachment of the cells, in fact, it was reported recently that osteoblasts like to adhere to the surface with micro-cracks [44]. Osteoblasts are anchorage dependent cells which require a surface to attach so that they produce and mineralize their extracellular matrix [45]. SEM images showed that the osteoblasts can attach to the surface of the microparticles with good extension of filopodia along their surface. The cells on day 5 had spherical morphology and were growing in small colonies sporadically along the surface of both P1 and P2. The colonies formed on P2 looked larger and denser compared to that on P1 indicating Zr not only promotes the cell-surface adhesion but also provides an environment to enhance the cell-cell adhesion. The cells grew into a larger colonies and were more elongated forming a sheet along the surface of microparticles by day 10. Similar results were reported for the morphology of OB-6 cells on the surface of microparticles [46].

One of the greatest advantages of using microparticles in tissue engineering is their ability to encapsulate the bioactive agents or drugs and release them in sustained manner [14, 46, 47]. Drug encapsulated microparticles showed the sustained release of drug for over 4 weeks period including a burst release on first day whereas drug coated microparticles released most of the absorbed drug in less than 2 weeks. Drug encapsulation results showed that the ability of fabricated microparticles to encapsulate cefazolin was low. The efficiency of drug encapsulation by the polymer depends on the chemical structure of polymer and drug itself [48]. Both CMC and cefazolin are negatively charged in aqueous solution that might have resulted in less drug incorporation into microparticles.

5. Conclusion

The main objective of the present study was to fabricate the CMC microparticles crosslinked with Zr ions and to assess if these microparticles are suitable for bone tissue engineering. By using Zr-ion as a cross-linker we were able to get rigid spherical microparticles which were further stabilized in CS solution. The structural stability of P2 was much better than that of P1 which indicated that Zr improves the mechanical stability of CMC microparticles. The surface roughness of the microparticles was well patterned obtained due to the uniform distribution of Zr along the surface. The surface of P2 looked rougher and structured compared to that of P1 which looked less rough and more granular. The use of Zr had no any adverse effects on the growth and proliferation of osteoblasts as indicated by live/dead cell assay results. We found that Zr induces the attachment of osteoblasts to the microparticles. A significant difference observed in the area of microparticles covered with viable osteoblasts between P1 and P2 indicate that Zr also enhances the osteoblasts proliferation without affecting the cell viability.

Research highlights.

Zirconium ions crosslinked carboxymethyl cellulose microparticles were fabricated.

The microparticles were further stabilized by complexation with chitosan.

The uniform distribution of zirconium promoted surface roughness.

The microparticles were not cytotoxic and zirconium promoted osteoblast attachment.

Sustained release of encapsulated drug was obtained from the microparticles.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the National Institute of Health (NIH) grant number R01DE023356 for providing us the financial support to conduct this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Qiu XY, Hu SW. “Smart” Materials Based on Cellulose: A Review of the Preparations, Properties, and Applications. Materials. 2013;6:738–81. doi: 10.3390/ma6030738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sannino A, Demitri C, Madaghiele M. Biodegradable Cellulose-based Hydrogels: Design and Applications. Materials. 2009:353–73. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang LY, Li YB, Xiong CD. Preparation and biological properties of a novel composite scaffold of nano-hydroxyapatite/chitosan/carboxymethyl cellulose for bone tissue engineering. J Biomed Sci. 2009:16. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-16-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasqui D, Torricelli P, De Cagna M, Fini M, Barbucci R. Carboxymethyl cellulose-hydroxyapatite hybrid hydrogel as a composite material for bone tissue engineering applications. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2014;102:1568–79. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raucci MG, Alvarez-Perez MA, Demitri C, Giugliano D, De Benedictis V, Sannino A, et al. Effect of citric acid crosslinking cellulose-based hydrogels on osteogenic differentiation. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2015;103:2045–56. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song S-H, Yun Y-P, Kim H-J, Park K, Kim SE, Song H-R. Bone Formation in a Rat Tibial Defect Model Using Carboxymethyl Cellulose/BioC/Bone Morphogenic Protein-2 Hybrid Materials. BioMed Research International. 2014;2014:8. doi: 10.1155/2014/230152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang W, Wang X, Wang S, Zhao J, Xu L, Zhu C, et al. The use of injectable sonication-induced silk hydrogel for VEGF(165) and BMP-2 delivery for elevation of the maxillary sinus floor. Biomaterials. 2011;32:9415–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arun Kumar R, Sivashanmugam A, Deepthi S, Iseki S, Chennazhi KP, Nair SV, et al. Injectable Chitin-Poly(ε-caprolactone)/Nanohydroxyapatite Composite Microgels Prepared by Simple Regeneration Technique for Bone Tissue Engineering. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 2015;7:9399–409. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b02685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kretlow JD, Young S, Klouda L, Wong M, Mikos AG. Injectable Biomaterials for Regenerating Complex Craniofacial Tissues. Advanced materials (Deerfield Beach, Fla) 2009;21:3368–93. doi: 10.1002/adma.200802009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yan J, Miao Y, Tan H, Zhou T, Ling Z, Chen Y, et al. Injectable alginate/hydroxyapatite gel scaffold combined with gelatin microspheres for drug delivery and bone tissue engineering. Materials Science and Engineering: C. 2016;63:274–84. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2016.02.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dyondi D, Webster TJ, Banerjee R. A nanoparticulate injectable hydrogel as a tissue engineering scaffold for multiple growth factor delivery for bone regeneration. International Journal of Nanomedicine. 2013;8:47–59. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S37953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oliveira MB, Mano JF. Polymer-Based Microparticles in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Biotechnol Prog. 2011;27:897–912. doi: 10.1002/btpr.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chau DYS, Agashi K, Shakesheff KM. Microparticles as tissue engineering scaffolds: manufacture, modification and manipulation. Materials Science and Technology. 2008;24:1031–44. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dreifke MB, Ebraheim NA, Jayasuriya AC. Investigation of potential injectable polymeric biomaterials for bone regeneration. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2013;101:2436–47. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silva GA, Coutinho OP, Ducheyne P, Shapiro IM, Reis RL. The effect of starch and starch-bioactive glass composite microparticles on the adhesion and expression of the osteoblastic phenotype of a bone cell line. Biomaterials. 2007;28:326–34. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim MS, Park SJ, Gu BK, Kim CH. Ionically crosslinked alginate-carboxymethyl cellulose beads for the delivery of protein therapeutics. Applied Surface Science. 2012;262:28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swamy BY, Yun Y-S. In vitro release of metformin from iron (III) cross-linked alginate–carboxymethyl cellulose hydrogel beads. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2015;77:114–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okazaki Y, Rao S, Asao S, Tateishi T. Effects of metallic concentrations other than Ti, Al and V on cell viability. Materials Transactions Jim. 1998;39:1070–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hallab NJ, Vermes C, Messina C, Roebuck KA, Glant TT, Jacobs JJ. Concentration- and composition-dependent effects of metal ions on human MG-63 osteoblasts. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 2002;60:420–33. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adair JH, Krarup HG, Venigalla S, Tsukada T. A Review of the Aqueous Chemistry of the Zirconium - Water System to 200°C. MRS Online Proceedings Library Archive. 1996:432. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hofer JK, Ezzet KA. A minimum 5-year follow-up of an oxidized zirconium femoral prosthesis used for total knee arthroplasty. The Knee. 2014;21:168–71. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sonntag R, Reinders J, Kretzer JP. What’s next? Alternative materials for articulation in total joint replacement. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:2434–41. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Q, Thouas GA. Metallic implant biomaterials. Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports. 2015;87:1–57. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lenz R, Mittelmeier W, Hansmann D, Brem R, Diehl P, Fritsche A, et al. Response of human osteoblasts exposed to wear particles generated at the interface of total hip stems and bone cement. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2009;89A:370–8. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen YJ, Roohani-Esfahani SI, Lu ZF, Zreiqat H, Dunstan CR. Zirconium Ions Up-Regulate the BMP/SMAD Signaling Pathway and Promote the Proliferation and Differentiation of Human Osteoblasts. Plos One. 2015:10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu YF, Zhang YF, Wu CT, Fang Y, Yang JH, Wang SL. The effect of zirconium incorporation on the physiochemical and biological properties of mesoporous bioactive glasses scaffolds. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials. 2011;143:311–9. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramaswamy Y, Wu C, Van Hummel A, Combes V, Grau G, Zreiqat H. The responses of osteoblasts, osteoclasts and endothelial cells to zirconium modified calcium-silicate-based ceramic. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4392–402. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta MS, Nicoll SB. Functional nucleus pulposus-like matrix assembly by human mesenchymal stromal cells is directed by macromer concentration in photocrosslinked carboxymethylcellulose hydrogels. Cell Tissue Res. 2014;358:527–39. doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-1962-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen C, Li H, Pan J, Yan Z, Yao Z, Fan W, et al. Biodegradable composite scaffolds of bioactive glass/chitosan/carboxymethyl cellulose for hemostatic and bone regeneration. Biotechnol Lett. 2015;37:457–65. doi: 10.1007/s10529-014-1697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teti G, Salvatore V, Focaroli S, Durante S, Mazzotti A, Dicarlo M, et al. In vitro osteogenic and odontogenic differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells seeded on carboxymethyl cellulose-hydroxyapatite hybrid hydrogel. Frontiers in physiology. 2015;6:297. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fraimow HS. Systemic Antimicrobial Therapy in Osteomyelitis. Seminars in Plastic Surgery. 2009;23:90–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu D, Chang PR, Deng S, Wang CY, Zhang BJ, Tian Y, et al. Fabrication and characterization of zirconium hydroxide-carboxymethyl cellulose sodium/plasticized Trichosanthes Kirilowii starch nanocomposites. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2011;86:1699–704. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takeuchi K, Okada S, Yukihiro S, Hajime I. The inhibitory effects of aluminum and iron on bone formation—in vivo and in vitro study. Pathophysiology. 1997;4:161–8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee B-A, Kim H-J, Xuan Y-Z, Park Y-J, Chung H-J, Kim Y-J. Osteoblastic behavior to zirconium coating on Ti-6Al-4V alloy. The Journal of Advanced Prosthodontics. 2014;6:512–20. doi: 10.4047/jap.2014.6.6.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosca C, Popa MI, Lisa G, Chitanu GC. Interaction of chitosan with natural or synthetic anionic polyelectrolytes. 1. The chitosan–carboxymethylcellulose complex. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2005;62:35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang LY, Li YB, Xiong CD. A novel composite membrane of chitosan-carboxymethyl cellulose polyelectrolyte complex membrane filled with nano-hydroxyapatite I. Preparation and properties Journal of Materials Science-Materials in Medicine. 2009;20:1645–52. doi: 10.1007/s10856-009-3720-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trouche E, Fullana SG, Mias C, Ceccaldi C, Tortosa F, Seguelas MH, et al. Evaluation of Alginate Microspheres for Mesenchymal Stem Cell Engraftment on Solid Organ. Cell Transplantation. 2010;19:1623–33. doi: 10.3727/096368910X514297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ninan N, Muthiah M, Park IK, Elain A, Thomas S, Grohens Y. Pectin/carboxymethyl cellulose/microfibrillated cellulose composite scaffolds for tissue engineering. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2013;98:877–85. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Han Y, Yan YY, Lu CG, Zhang YM, Xu KW. Bioactivity and osteoblast response of the micro-arc oxidized zirconia films. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2009;88A:117–27. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herath HM, Di Silvio L, Evans JR. Osteoblast response to zirconia surfaces with different topographies. Materials science & engineering C, Materials for biological applications. 2015;57:363–70. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2015.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Assal PA. The osseointegration of zirconia dental implants. Schweizer Monatsschrift fur Zahnmedizin = Revue mensuelle suisse d’odonto-stomatologie = Rivista mensile svizzera di odontologia e stomatologia / SSO. 2013;123:644–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kanchana SSH. Zirconia a Bio-inert Implant Material. IOSR Journal oF Dental and Medical Sciences. 2013;12:66–7. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ball M, Grant DM, Lo WJ, Scotchford CA. The effect of different surface morphology and roughness on osteoblast-like cells. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;86:637–47. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu Y, Zhu R, Ma J, Weng Z, Wang Y, Shi X, et al. In vitro cell proliferation evaluation of porous nano-zirconia scaffolds with different porosity for bone tissue engineering. Biomedical materials (Bristol, England) 2015;10:055009. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/10/5/055009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boyan BD, Lohmann CH, Dean DD, Sylvia VL, Cochran DL, Schwartz Z. Mechanisms involved in osteoblast response to implant surface morphology. Annual Review of Materials Research. 2001;31:357–71. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mantripragada VP, Jayasuriya AC. Injectable chitosan microparticles incorporating bone morphogenetic protein-7 for bone tissue regeneration. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2014;102:4276–89. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mantripragada VP, Jayasuriya AC. IGF-1 release kinetics from chitosan microparticles fabricated using environmentally benign conditions. Materials science & engineering C, Materials for biological applications. 2014;42:506–16. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2014.05.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mitragotri S, Burke PA, Langer R. Overcoming the challenges in administering biopharmaceuticals: formulation and delivery strategies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:655–72. doi: 10.1038/nrd4363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]