Abstract

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) is in the process of updating antenatal care (ANC) guidelines.

Objectives

To map the existing clinical practice guidelines related to routine ANC for healthy women and to summarise all practices considered during routine ANC.

Search strategy

A systematic search in four databases for all clinical practice guidelines published after January 2000.

Selection criteria

Two researchers independently assessed the list of potentially eligible publications.

Data collection and analysis

Information on scope of the guideline, type of practice, associated gestational age, recommendation type and the source of evidence were mapped.

Main results

Of 1866 references, we identified 85 guidelines focusing on the ANC period: 15 pertaining to routine ANC and 70 pertaining to specific situations. A total of 135 interventions from routine ANC guidelines were extracted, and categorised as clinical interventions (n = 80), screening/diagnostic procedures (n = 47) and health systems related (n = 8). Screening interventions, (syphilis, anaemia) were the most common practices. Within the 70 specific situation guidelines, 102 recommendations were identified. Overall, for 33 (out of 171) interventions there were conflicting recommendations provided by the different guidelines.

Conclusion

Mapping the current guidelines including practices related to routine ANC informed the scoping phase for the WHO guideline for ANC. Our analysis indicates that guideline development processes may lead to different recommendations, due to context, evidence base or assessment of evidence. It would be useful for guideline developers to map and refer to other similar guidelines and, where relevant, explore the discrepancies in recommendations and others.

Tweetable abstract

We identified existing ANC guidelines and mapped scope, practices, recommendations and source of evidence.

Keywords: Antenatal care, guidelines, pregnancy, routine care, World Health Organization

Tweetable abstract

We identified existing ANC guidelines and mapped scope, practices, recommendations and source of evidence.

Introduction

Routine antenatal care (ANC) is defined as the care provided by health practitioners (or others) to all pregnant women to ensure the best health conditions for the women and their fetuses during pregnancy. The basic components of the ANC include risk identification, prevention and management of pregnancy‐specific or concomitant diseases, education and health promotion. The goal‐oriented approach with reduced number of visits, currently recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO),1 was incorporated into WHO's Integrated Management of Pregnancy and Childbirth guidelines.2 However, even though the number and content of antenatal visits have been appraised and summarised in systematic reviews during recent years,3, 4 an evaluation of the evidence is needed5 because recommendations may have changed over time in light of new and compelling evidence.6

As part of the WHO's normative work on supporting evidence‐informed policies and practices, WHO is in the process of updating the ANC guidelines to provide a foundation for the strategic policy and programme development needed to ensure the sustainable implementation of effective interventions. To inform the development of these new guidelines, a mapping review was undertaken to provide an overview of all the interventions offered to healthy pregnant women that have been considered in clinical guidelines between 2000 and 2014.

This review has three aims: (1) to map the existing clinical practice guidelines related to routine ANC for healthy women; (2) to summarise all the procedures and interventions considered and recommended during routine ANC from both guidelines covering ANC in general, and from disease‐specific (or procedure‐specific) clinical guidelines aimed at the general ANC population; and (3) to assess the consistency of recommendations across the identified guidelines.

Methods

In December 2013, we conducted a systematic search for evidence‐based guidelines in the following databases: PubMed, LILACS (the most important and comprehensive index of scientific and technical literature of Latin America and the Caribbean); TRIP (Turning Research into Practice) database,7 a medical search engine with emphasis on evidence‐based medicine and clinical guidelines and queries, and the Guidelines repository maintained by GFMER (Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research).8 To identify as many relevant guidelines as possible, we chose a broad search strategy. In PubMed, we used the words ‘pregnancy or prenatal or antenatal’ and ‘care or management or screening’, selecting guideline/practice guideline (for article type), human (for species) and female (for sex) in the advanced search. In LILACS, we combined the words on the category DeCS N04.761.700.350.650 (clinical practice guidelines and all its synonyms in Portuguese, Spanish and English) and ‘prenatal or antenatal or pregnancy’. In TRIP, we combined the words ‘antenatal or prenatal or pregnancy’ and ‘clinical or practice’ and ‘guideline* or guidance* or recommendation* or advice’. Additionally, we checked all the references from the retrieved papers. We limited our search to all clinical practice guidelines published after January 2000.

Two researchers independently assessed the list of potentially eligible citations. Differences were resolved by discussion and consensus or the involvement of a third researcher. We excluded references based on titles and abstracts (when available) if the paper was one of the following: (1) not a guideline (as per the Institute of Medicine definition);9 (2) related to interventions/procedures not applicable during the ANC period; (3) published before 2000; (4) related to interventions/procedures recommended for the management of a recognised illness during pregnancy such as diabetes or hypertension. The full‐texts of the included guidelines were assessed for data extraction.

Two researchers independently extracted the information describing the guideline: title, year and country of publication, scope of the guideline (whether it covers full ANC or only a specific situation such as ultrasound in the first trimester of pregnancy or screening for infections during pregnancy). Each practice within the included guidelines was also described and characterised as follows: type of practice (screening/diagnostic test, clinical intervention or health system intervention), gestational age, whether or not it is recommended and the source of such recommendation. All the information was entered into a predesigned database, based on the categories described above.

Results

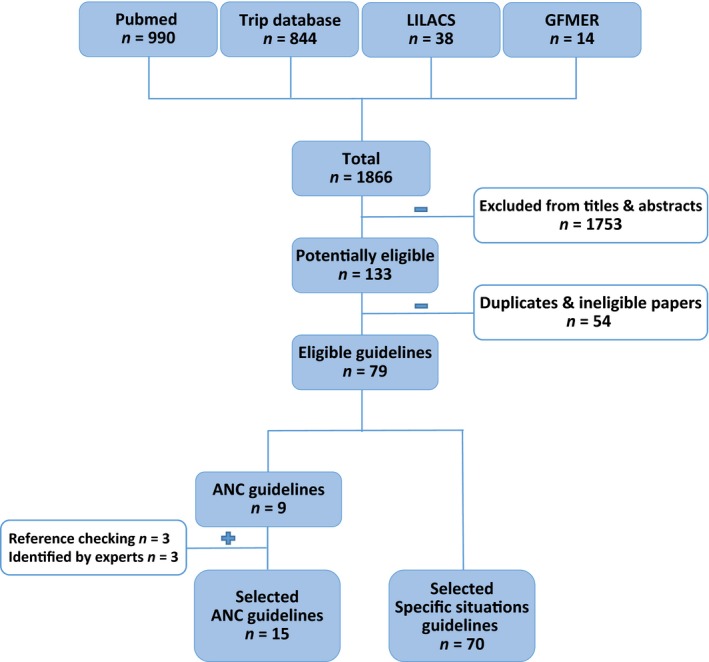

The database search for routine ANC guidelines and for guidelines containing interventions that can be offered during the ANC period returned 1866 results. The latter will be referred to as specific situations guidelines. After title and abstract review, 133 were included for full text assessment. Of these, 27 corresponded to potentially eligible ANC guidelines and 106 to potentially eligible specific situations guidelines. After removal of duplicates and ineligible papers, nine full ANC and 70 specific situations guidelines were included in the final database. Reference checking led to three additional ANC guidelines and participants at an ANC expert meeting held in Geneva in April 2014 contributed another three (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of article selection following literature searches in PubMed, LILACS, TRIP database, the GFMER guidelines repository, references check and contributions from experts. Date of last search April 2014.

Overall, 15 guidelines make recommendations on routine ANC. Three of these were issued by WHO,10, 11, 12 and the rest by governmental or nongovernmental organisations from the USA,13, 14, 15 UK,16, 17 Canada,18, 19 Australia,20 Hong Kong,21 India,22 Japan23 and Poland.24 All were published between 2005 and 2012. We also identified 70 specific situations guidelines published between 2002 and 2014. Of these, 91% were from the USA,25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59 UK60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76 and Canada.77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88 The remaining were from Australia,89 Brazil,90 Mexico,91 Poland,92 Spain93 and Uruguay.94

Routine ANC guidelines and identified interventions

We extracted 135 interventions from routine ANC guidelines, which were categorised as clinical interventions (n = 80), screening/diagnostic procedures (n = 47) and health systems recommendations (n = 8) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Types of interventions considered in routine ANC and specific situation guidelines

| Routine ANC guidelines (n = 135) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening / diagnostic procedures, n (%) | Clinical interventions, n (%) | Health systems n (%) | ||||

| 47 (35) | 80 (59) | 8 (6) | ||||

| Laboratory | Clinical | US/Mix | Educational | Prophylaxis | Management | |

| 21 (16) | 18 (13) | 8 (6) | 27 (20) | 26 (19) | 27 (20) | 8 (6) |

| Specific situation guidelines (n = 102) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening / diagnostic procedures, n (%) | Clinical interventions, n (%) | Health systems n (%) | ||||

| 37 (36) | 60 (59) | 5 (5) | ||||

| Laboratory | Clinical | US/Mix | Educational | Prophylaxis | Management | |

| 22 (22) | 6 (6) | 9 (9) | 22 (22) | 18 (18) | 20 (20) | 5 (5) |

Clinical interventions included a wide range of practices. One third (n = 27) were educational, such as advice for breastfeeding, family planning or illicit drug or alcohol consumption reduction or cessation. Another third (n = 26) were prophylactic interventions recommended during routine ANC, including rhesus D (RhD) immunoprophylaxis, influenza immunisation or routine mineral/vitamin supplementation to prevent specific conditions. The remaining 27 interventions were about the management of conditions such as nausea and vomiting, constipation or commonly detected disorders such as anaemia or vaginal discharge.

Regarding screening or diagnostic procedures, almost half (21 out of 47) were about laboratory procedures such as routine ABO, RhD testing or different laboratory tests to screen for diseases like diabetes, anaemia or infections. Eighteen were recommendations for clinical manoeuvres for screening, including symphysis–fundal height measurement, blood pressure measurement or fetal movement count. Most of the recommendations for screening using images were on ultrasound (n = 8) alone or combined with laboratory tests if it was for a specific condition (e.g. screening for aneuploidy).

Recommendations about health systems organisation included indications on who should provide care, the use of incentives for use of ANC or on documentation of care provided during ANC.

Table 2 summarises the individual practices and how often they were considered in routine ANC guidelines. Overall, screening interventions were the most common practices taken into account in these guidelines. They include screening for syphilis, HIV, anaemia (haemoglobin levels) and pre‐eclampsia (by measuring blood pressure and proteinuria) and routine ABO, RhD testing. Regarding educational activities, advice on nutrition during pregnancy, exercise and/or rest, tobacco smoking cessation or reduction were frequently considered. Advice on breastfeeding was included in only nine (out of 15) routine ANC guidelines. Folic acid and iron supplementation were the only two clinical interventions recommended in the majority of guidelines (12 and 10, respectively).

Table 2.

Interventions considered in routine ANC guidelines and number of guidelines recommending each intervention

| Screening / diagnostic procedures | Clinical interventions | Health systems | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| STDs (syphilis) | 14 (93) | ||

| STDs (HIV), anaemia and pre‐eclampsia (BP + proteinuria) | 13 (87) | ||

| Routine ABO, D Rhesus testing | Supplementation: folic acid | 12 (80) | |

| Weight and BMI, infections (rubella, hepatitis B) | Advice: nutrition, exercise and/or rest, smoking cessation | 11 (73) | |

| Early ultrasound (first and second trimester), GDM and asymptomatic bacteriuria | Supplementation: iron | 10 (67) | |

| Auscultation of fetal heart, symphysis‐fundal height, Down syndrome | Advice: breastfeeding | 9 (60) | |

| Abdominal palpation, infections (bacterial vaginosis, Chlamydia) | Advice: alcohol intake, sexual intercourse, travelling. Prophylaxis: RhD | 8 (53) | |

| Infections (toxoplasmosis, hepatitis C), domestic violence | Advice: work. Management: nausea and vomiting | 7 (47) | |

| Substance use, for cervical cancer, group B streptococcus | Supplementation: vitamin D. Vaccines: tetanus | 6 (40) | |

| Breast and pelvic examination, preterm labour, postnatal depression | Advice: labour and delivery, illicit drug use and medications. Supplementation: vitamin A. Vaccines: influenza | Frequency of visits | 5 (33) |

| Fetal movement count, pelvimetry, late ultrasound and/or Doppler. tobacco use and exposure, sickle cell and thalassaemia | Advice: information on pregnancy and family planning. Management: oral health, constipation, breech presentation | 4 (27) | |

| History and physical examination, evaluation of oedema. Risk profile, fetal wellbeing and fetal anomalies. Infections (CMV), alcohol abuse and thyroid dysfunction. Antenatal cardiotocography, urinalysis | Advice: warning signs, preterm labour, prenatal screening. Prophylaxis: anti‐malarial drugs. Supplementation: calcium. Management: vaginal discharge |

Care documents Place of delivery Provider of ANC |

3 (20) |

| Infections (parvovirus B19) | Advice: course of care, hot tubs and saunas, hair treatments, HIV and other STD, vaginal birth after caesarean. Prophylaxis: steroids for women at risk of preterm birth. Management: haemorrhoids, varicose veins, backache, vaginal bleeding | First antenatal visit | 2 (13) |

| Infections (candidiasis), psycho‐social risk factors | Advice: healthy lifestyle, self‐care, emotional wellbeing, tattoos in lower back, shaken baby syndrome, cystic fibrosis, warfarin use in pregnancy. Prophylaxis: low‐dose aspirin, DVT/PTE, MTCH transmission of HIV. Vaccines: hepatitis B, rubella, varicella, pertussis, pneumococcus. Supplementation: vitamin B6, vitamin C, magnesium, zinc, multivitamins. Management: unintended pregnancy, late pregnancy symptoms, fever, swelling, heartburn, frequency of urination, palpitations, breathlessness, fatigability, syphilis, HSV, HBV, parasitosis, anaemia, carpal tunnel syndrome, depression, drug abuse, obesity, post‐term pregnancy. Vision Care Follow‐up of modifiable risk factors. |

Antenatal classes Evaluation of satisfaction Place of ANC visit |

1 (7) |

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CMV, cytomegalovirus; DVT/PTE, deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary thromboembolism; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HSV, herpes simplex virus; MTCH, mother‐to‐child; STDs, sexually transmitted diseases.

Specific situations guidelines and identified interventions

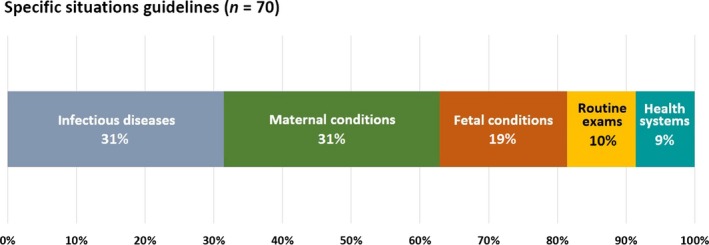

From 70 specific situations guidelines, 22 (31%) were related to infectious diseases. They included recommendations for the screening or management of viral hepatitis, group B streptococcus, syphilis, toxoplasmosis, rubella, herpes simplex virus, bacterial vaginosis, chlamydial infections, cytomegalovirus, HIV, influenza H1N1 virus and asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy. The other 22 guidelines (31%) covered the detection or supervision of maternal conditions such as gestational diabetes mellitus, thrombophilia, mental illness, anaemia, asthma, thyroid disease, or haemoglobinopathies, the management of common conditions like nausea and vomiting during pregnancy, anti‐RhD immunoprophylaxis or general recommendations for nutrition, oral health, alcohol intake or exercise in water geared towards the specific condition covered by the guideline. Thirteen guidelines (19%) targeted fetal screening for aneuploidy and/or neural tube defects, fetal growth restriction or preterm birth, prophylactic measures such as antenatal corticosteroids or cervical cerclage to prevent preterm delivery in women at risk and management of twin pregnancies. Seven guidelines (10%) were limited to the use of routine examinations and ultrasound in pregnancy and the remaining six (9%) were oriented to health system organisation for ANC including rural maternity care, preconception health care or ANC under complex social situations (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Main scope of the ‘specific situation’ guidelines (not related to full ANC) containing interventions that can be offered during the ANC period for low risk women.

Overall, we extracted 102 interventions/recommendations from the specific situations guidelines (Table 1). They were also categorised as clinical interventions (n = 60), from which 22 and 18 were educational and prophylactic interventions, respectively, and the remaining 20 were related to the management of clinical conditions. Recommendations for screening or diagnosis included laboratory procedures (n = 22), clinical manoeuvres (n = 6), ultrasound (n = 3) and mixed methods (n = 6). Health systems recommendations (n = 5) included topics such as documentation of care, health insurance coverage or integration of services.

Recommendations extracted from the specific situations guidelines are directly related to the scope of each guideline. Hence, screening for fetal anomalies, screening for Down syndrome, early ultrasound (first and second trimester) and late ultrasound and/or Doppler were the most commonly included interventions under these guidelines.

Consistency of recommendations: agreement between guidelines

From both routine ANC guidelines and specific situations guidelines, we extracted 171 interventions. The fact that an intervention is mentioned in a given guideline does not necessarily mean a recommendation to use that specific practice. For example, vitamin C or magnesium supplementation were considered and not recommended for use in two guidelines.10, 20

However, there are cases in which we could detect disagreement among different guidelines regarding the direction of the recommendation. Hence, for 33 (out of 171) interventions there were conflicting recommendations provided by different guidelines. As an example, routine screening for toxoplasmosis is mentioned in ten guidelines, seven routine ANC and three specific situations (one related to routine examinations during ANC and the other two specifically oriented to toxoplasmosis detection and management). Routine screening is not recommended in six of these guidelines (five ANC, one specific situations) and is recommended in four (two of routine ANC and two specific situations). Guidelines recommending screening for toxoplasmosis were published between 2005 and 2013 and those recommending no screening were published between 2005 and 2011. We have not evaluated the quality of the evidence supporting conflicting recommendations, as making judgements for individual interventions was not the objective of this mapping. Interested readers should refer to the Supplementary material (Table S1), which summarises the inconsistent recommendations across the included guidelines.

Discussion

Main findings

Our review identified a total of 85 guidelines focusing on the ANC period—15 routine ANC and 70 specific situations relevant to the ANC period. As described by others,95 this overview shows a wide disparity among ANC and specific situations guidelines on both the number and types of interventions proposed for routine ANC. From the 135 interventions identified in routine ANC guidelines, 64 were also considered in other specific situation guidelines, due mainly to the scope of the latter. Seven specific situation guidelines were limited only to ultrasound in pregnancy. On the other hand, we could identify 37 interventions from disease‐specific (or procedure‐specific) clinical guidelines aimed at the general ANC population, not considered in any of the 15 identified ANC papers, such as screening for thrombophilia or herpes simplex virus, or advice for oral health.

Screening for infectious diseases was the most frequently endorsed intervention among the included ANC guidelines, as well as the majority of the identified specific situations guidelines. Syphilis, HIV, asymptomatic bacteriuria, hepatitis B and rubella were in the top of the list, with strong agreement. Other infections such as toxoplasmosis, group B streptococcus, herpes simplex virus or cytomegalovirus were less consistently considered and sometimes recommendations were in opposite directions, as also reported by Piso et al.96

Strengths and limitations

This was an extensive search to inform the development of WHO guidelines. We limited our search to four of the most popular sources of potentially eligible guidelines (PubMed, LILACS, TRIP and the GFMER guideline repository), reference searches and expert panel advice. Citations of guidelines published in medical journals are increasingly searchable through Medline, which has developed a comprehensive search engine for guidelines search97 and related articles such as impact or economic evaluations of guidelines. LILAC contains nearly 800 000 records including theses, chapters of theses, books, chapters of books, congress and conference proceedings, technical and scientific reports, government publications and articles from more than 900 journals from Latin America and the Caribbean in both Spanish and Portuguese. The TRIP database allows the user to search several electronic evidence resources at once, such as Bandolier, Evidence‐Based Medicine, MeReC (UK National Prescribing Centre), Rapid clinical query answer for GPs (formerly ATTRACT), National Library for Health, Primary Care Question‐Answering Service, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Swedish Council on Technology Assessment, Agency for Health Care Research and Quality: Evidence‐Based Practice, National Guideline Clearing House (USA), Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (UK), Royal Colleges, PRODIGY (UK) and textbooks from eMedicine and GPnotebook.98 However, some local/national guidelines available in other specific sites such as Ministries of Health web pages, other professional associations or the grey literature, not referenced in these databases may have been missed and this is a major limitation of this review. We consider that, despite these limitations, the likelihood that we missed an important intervention or procedure is very unlikely.

We have not assessed the guidelines’ methodological rigour and transparency by using tools such as the Agree II99 or other instruments. Our main interest was to identify the individual interventions considered in these documents so that important or relevant manoeuvres, tests and procedures were not omitted. Our aim was not to guide clinical practice for individual practitioners.

Interpretation

It is worth noting that health promotion (one of the core contents of routine ANC for healthy women) was not consistently addressed in the included guidelines. Advice regarding nutrition during pregnancy, exercise and/or rest and tobacco smoking cessation or reduction was an explicit recommendation in 11 (out of 15) documents, and breastfeeding advice was considered in nine, family planning in four, and prevention of and protection from HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases only in two.

Supplementation with iron and/or folic acid, RhD immunoprophylaxis and management of nausea and vomiting were the only clinical interventions for routine ANC included in more than 50% of the guidelines. Among this group, those related to vitamin and/or mineral supplementation were the ones with contradictory recommendations. Nearly half of guidelines considering iron, calcium and vitamins A and D recommended for supplementation, whereas the other half recommended against.

The source of such heterogeneity is uncertain and maybe difficult to identify as it may relate to multiple causes. We included guidelines published between 2000 and 2014; newer guidelines may contain more up‐to‐date evidence. It was stated that, as a rule, guidelines should be reassessed for validity every 3 years.100 However, in some cases, the references on which the authors based their recommendations (when published) were contemporary, yet from different sources. Although not always explicit, different approaches for appraising and grading the evidence and for making the recommendation, such as the more or less liberal use of expert consensus or the choice of alternative grading systems, may explain such differences.

Setting is another issue to take into account when analysing the frequency with which some interventions were considered in different guidelines. Three (out of 15) ANC guidelines were multinational (WHO), one was from a lower‐middle‐income country (India) and another from an upper‐middle‐income country (Poland). The remainder came from high‐income countries.101 As previously stated, 91% of the specific situations guidelines were issued in the USA, UK and Canada, so it is not surprising that screening for fetal anomalies (including genetic testing for Down syndrome) and ultrasound at different timeframes during pregnancy were commonly included. It is possible that guidelines from other countries considered this level of investigation to be out of scope (for a variety of reasons including infrastructure constraints or cultural values). The low representation of low‐ and middle‐income countries in this mapping could be explained by the databases searched, but may also have been a result of the prespecified timeframe limit. It should be noted that clinical practice guidelines from low‐ and middle‐income countries were identified; however, some were excluded because they were published before 2000, and others, especially those from the Commonwealth were excluded because they fully adhered to British guidelines, which were included as part of this analysis.

Conclusion

This overview is not intended to inform clinical practice. By mapping the current guidelines and included practices related to routine ANC, this review informed the scoping phase of the new WHO ANC guideline update process. Guideline development, be it national or international in scope, relies on the synthesis of the existing body of evidence. Our analysis indicates that this process may lead to different recommendations, due to context, evidence base and/or assessment and grading of evidence. Therefore, it would be useful for guideline developers to map and refer to other similar guidelines and, where relevant, explore the discrepancies in their recommendations and those of others.

Disclosure of interests

Full disclosure of interests available to view online as supporting information.

Contribution of authorship

EA, AMG and OT conceived the mapping overview. All authors developed the methodology. VD and MC performed the literature search and prepared the vital registration data. VD, MC and EA considered papers for inclusion and extracted the data. EA, VD, MC and OT drafted the text and tables. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Details of ethics approval

Not required.

Funding

This review was funded by Grant Number OPP1084319 from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Supporting information

Table S1. Interventions with recommendations in opposite directions among different guidelines.

Acknowledgements

This paper was written as part of the Adding Content to Contact project, which was made possible by Grant Number OPP1084319 from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and was a collaboration between the Maternal Health Task Force and 361 Department of Global Health and Population at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, HRP/WHO, and ICS Integrare.

Edgardo A, Monica C, Virginia D, Ӧzge T, Metin GA. Antenatal care for healthy pregnant women: a mapping of interventions from existing guidelines to inform the development of new WHO guidance on antenatal care. BJOG 2016;123:519–528.

Linked article This article is commented on by N van den Broek, p. 558 in this issue. To view this mini commentary visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13937.

References

- 1. The World Health Organization 2001 WHO antenatal care randomized trial. Manual for the implementation of the new model. [www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal_health/RHR_01_30/en/]. Accessed 20 December 2013.

- 2. Pregnancy, Childbirth, Postpartum and Newborn Care: A Guide for Essential Practice. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carroli G, Villar J, Piaggio G, Khan‐Neelofur D, Gülmezoglu M, Mugford M, et al. WHO systematic review of randomised controlled trials of routine antenatal care. Lancet 2001;357:1565–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dowswell T, Carroli G, Duley L, Gates S, Gülmezoglu AM, Khan‐Neelofur D, et al. Alternative versus standard packages of antenatal care for low‐risk pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010; (10):CD000934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carroli G, Rooney C, Villar J. How effective is antenatal care in preventing maternal mortality and serious morbidity? An overview of the evidence Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2001;15 (Suppl 1):1–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mathai M. Alternative versus standard packages of antenatal care for low‐risk pregnancy: RHL commentary (last revised: 1 January 2011). The WHO Reproductive Health Library; Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 7. TRIP Database [www.tripdatabase.com/].

- 8. Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research [www.gfmer.ch/Guidelines/Obstetrics_gynecology_guidelines.php].

- 9. Institute of Medicine , Graham R, Mancher M, Wolman DM, Greenfield S, Steinberg E, editors. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Washington (DC): National Academies Press, 2011. pp. 2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Di Mario S, Basevi V, Gori G, Spettoli D. What is the effectiveness of antenatal care? (Supplement) Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe (Health Evidence Network report; 2005. [www.euro.who.int/data/assets/pdf_file/0005/74660/E87997.pdf]. Accessed 21 December 2013.

- 11. Integrated Management of Pregnancy and Childbirth . Pregnancy, Childbirth, Postpartum and Newborn Care: A Guide for Essential Practice. Geneva: World Health Organization. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. The Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health . A Global Review of the Key Interventions Related to Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (Rmnch). Geneva: PMNCH; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13. AAP/ACOG . Guideline for Perinatal Care, 6th edition Washington, DC: American Academy of Pediatrics (and) the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Department of Veteran Affairs, Department of Defense . VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Pregnancy. Washington, DC: Department of Veteran Affairs, Department of Defense, 2009. pp. 163. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Akkerman D, Cleland L, Croft G, Eskuchen K, Heim C, Levine A, et al. Routine Prenatal Care. Bloomington (MN): Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI), 2012. pp. 115. [Google Scholar]

- 16. National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health . Antenatal Care. Routine Care for the Healthy Pregnant Woman. Welsh A, editor. Dorchester: Henry Ling Ltd, The Dorset Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Willacy H. Antenatal Care. Document ID: 1807 Version: 28. 2012. Patient.co.uk [www.patient.co.uk/doctor/antenatal-care]. Accessed 20 December 2013.

- 18. Kirkham C, Harris S, Grzybowski S. Evidence‐based prenatal care: part I. General prenatal care and counseling issues. Am Fam Physician 2005;71:1307–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. BCPHP . Obstetric Guideline 19. Maternity Care Pathway, 2010. Vancouver: BC Perinatal Health Program, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council 2012, Clinical Practice Guidelines: Antenatal Care – Module 1. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, Canberra. [www.health.gov.au/antenatal]. Accessed 19 December 2013.

- 21. The Hong Kong College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, A Foundation College of Hong Kong Academy of Medicine . Guidelines on Antenatal Care. HKCOG Number 12 (Part I and II). Hong Kong: HKCOG; September 2008.

- 22. Guidelines for Antenatal Care and Skilled Attendance at Birth 2010. Maternal Health Division. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Government of India.

- 23. Minakami H, Hiramatsu Y, Koresawa M, Fujii T, Hamada H, Iitsuka Y, et al. Guidelines for obstetrical practice in Japan: Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (JSOG) and Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (JAOG) 2011 edition. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2011;37:1174–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Polskie Towarzystwo Ginekologiczne . Rekomendacje Polskiego Towarzystwa Ginekologicznego w zakresie opieki przedporodowej w ciazy o prawidlowym przebiegu (Polish Gynaecological Society 2005. Recommendations of Polish Gynaecological Association regarding antenatal care in normal pregnancy). 2005.

- 25. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 37. Obstet Gynecol 2002;100:387–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. American Academy of Family Physicians . Preconception Health Care. Am Fam Physician 2002;65:2507–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . Neural tube defects. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 44. Obstet Gynecol 2003;102:203–13.12850637 [Google Scholar]

- 28. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 52. Obstet Gynecol 2004;103:803–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . Pregestational diabetes mellitus. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 60. Obstet Gynecol 2005;105:675–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . Management of alloimmunization during pregnancy. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 75. Obstet Gynecol 2006;108:457–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Recommendations to Improve Preconception Health and Health Care—United States. A Report of the CDC/ATSDR Preconception Care Work Group and the Select Panel on Preconception Care. April 21, 2006/55(RR06); pp. 1–23. [PubMed]

- 32. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . Management of herpes in pregnancy. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 82. Obstet Gynecol 2007;109:1489–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . Hemoglobinopathies in pregnancy. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 78. Obstet Gynecol 2007;109:229–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . Invasive prenatal testing for aneuploidy. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 88. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:1459–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . Screening for fetal chromosomal abnormalities. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 77. Obstet Gynecol 2007;109:217–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . Viral hepatitis in pregnancy. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 86. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:941–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Screening for Chlamydial Infection: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:128–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. First trimester diagnosis and screening for fetal aneuploidy. ACMG Practice Guidelines. Genet Med 2008;10:73–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . Anemia in pregnancy. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 95. Obstet Gynecol 2008;112:201–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . Asthma in pregnancy. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 90. Obstet Gynecol 2008;111:457–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . Use of psychiatric medications during pregnancy and lactation. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 92. Obstet Gynecol 2008;111:1001–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:759–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy to prevent preterm delivery: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:214–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. American College of Medical Genetics Technical standards and guidelines: prenatal screening for Down syndrome that includes first trimester biochemistry and or ultrasound measurement. Genetics Med 2009;11:669–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Screening for hepatitis B virus infection in pregnancy: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:869–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Screening for syphilis infection in pregnancy: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:705–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Prevention of Perinatal Group B Streptoccocal Disease. Revised Guidelines from CDC. Atlanta: CDC, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 48. International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups 2010 . Recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2010;33:676–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry . Guideline on perinatal oral health care: revised 2011. Reference manual V 36 / NO 6 14 / 15. pp. 135–40.

- 50. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 123. Thromboembolism in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2011;118:718–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bollman DL (editor). Perinatal Services Guidelines for Care: A Compilation of Current Standards. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Public Health, Maternal Child and Adolescent Health Division, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 52. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 132. Antiphospholipid syndrome. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:1514–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 130. Prediction and prevention of preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:964–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . ACOG Practice bulletin No. 134: fetal growth restriction. Obstet Gynecol 2013;121:1122–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 137. Gestational diabetes. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122:406–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 138. Inherited thrombophilias in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122:706–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2013–2014. MMWR Recomm Rep 2013;62:1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 142. Cerclage for the management of cervical insufficiency. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:372–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 144. Multifetal gestations: twin, triplet, and higher‐order multifetal pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:1118–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) . Antenatal and postnatal mental health. Clinical management and service guidance Issued: February 2007 last modified: April 2007. NICE clinical guideline 45. London: NICE, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 61. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) . Routine antenatal anti‐D prophylaxis for women who are rhesus D negative. Review of NICE technology appraisal guidance 41. NICE technology appraisal guidance 156. London: NICE, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 62. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) . Improving the nutrition of pregnant and breastfeeding mothers and children in low‐income households. (Public health guidance; no. 11). London: NICE, 2008. pp. 105. [Google Scholar]

- 63. UK National Guidelines on the Management of Syphilis. Int J STD AIDS 2008;19:729–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Women's Health (ACPWH) . Aquanatal Guidelines. Guidance of Antenatal and Postnatal Excercise in Water. London: ACPWH/POGP, 2013. pp. 12. [Google Scholar]

- 65. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) . Pregnancy and complex social factors. A model for service provision for pregnant women with complex social factors. NICE clinical guideline 110. London: NICE; [www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg110/chapter/]. Accessed 18 December 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists . Antenatal Corticosteroids to Reduce Neonatal Morbidity and Mortality. Green‐top Guideline No. 7. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. UK National Screening Committee . Screening for hepatitis C in pregnancy. Policy Position Statement. London: UK National Screening Committee. [Google Scholar]

- 68. UK National Screening Committee . Policy Review. Screening for Toxoplasmosis Policy Position Statement. London: UK National Screening Committee. [Google Scholar]

- 69. British HIV Association guidelines for the management of HIV infection in pregnant women 2012. HIV Med 2012;13(Suppl 2):87–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. RCOG Green Top Guideline No. 36. The prevention of early onset neonatal Group B Streptococcal Disease. Orv Hetil 2014;155:1167–72.25016449 [Google Scholar]

- 71. UK National Screening Committee . Rubella Susceptibility Screening in Pregnancy. Policy Position Statement. London: UK National Screening Committee. [Google Scholar]

- 72. UK National Screening Committee . Asymptomatic Bacteriuria Screening in Pregnancy Policy Position Statement. London: UK National Screening Committee. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Screening for Syphilis in Pregnancy. External Review Against Programme Appraisal Criteria for the UK National Screening Committee (UK NSC) Version: 1. London: UK National Screening Committee, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 74. ISUOG Practice Guidelines: use of Doppler ultrasonography in obstetrics. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2013;41:233–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. ISUOG Practice Guidelines (updated): sonographic screening examination of the fetal heart. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2013;41:348–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. ISUOG Practice Guidelines: performance of first‐trimester ultrasound scan. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2013;41:102–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ciapponi A. Actualización y combinación de las guías de cuidados preventivos de las fuerzas de tareas de EE.UU. y Canadá (Quinta parte). Evid Act Pract Ambul 2010;13:64–7. [http://www.evidencia.org/hitalba-paginaarticulo.php?cod_producto=2689&origen=2#sthash.SlIwNFdF.dpuf]. Accessed 22 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 78. The Use of Folic Acid for the Prevention of Neural Tube Defects and Other Congenital Anomalies. SOGC Clinical Practice Guideline No.138. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2003;25:959–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. The use of first trimester ultrasound. SOGC Clinical Practice Guidelines. No 135. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2003;25:864–9.14532956 [Google Scholar]

- 80. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: Canadian guidelines for diagnosis. CMAJ 2005;172(5 Suppl):S1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Screening and management of Bacterial Vaginosis in Pregnancy. SOGC Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2008;30:702–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Guideline for Management of Herpes Simplex Virus in Pregnancy. SOGC Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2008;30:514–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Rubella in Pregnancy. SOGC Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2008;30:152–8.18254998 [Google Scholar]

- 84. Yinon Y, Yudin MH, Farine D, SOGC Clinical Practice Guidelines . Cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2010;240:348–54.20500943 [Google Scholar]

- 85. Prenatal Screening for Down syndrome, Trisomy 18 and open neural tube defects. Perinatal Service BC Obstetric Guideline 17.

- 86. Management guideline for pregnant women and neonates born to women with suspected or confirmed pandemic H1N1 influenza. Perinatal Services BC 2011.

- 87. SOGC Clinical Practice Guidelines . Toxoplasmosis in pregnancy: prevention, screening, and treatment. No. 285, January 2013. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2013;35(1 eSuppl A):S1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Iglesias S, Grzybowski S, Klein MC, Gagné GP, Lalonde A. JPP, Working Group. Joint Position Paper on Rural Maternity Care. Can Fam Physician 1998;44:831–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) . National Guidance on Collaborative Maternity Care. Canberra: NHMRC, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 90. Avaliação dos exames de rotina no pré‐natal (Partes 1). Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet 2009;31:148–55.//Avaliação dos exames de rotina no pré‐natal (Partes 2). Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet 2009;31:367–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Prevencion de la desnutricion de la madre y el niño: el componente de nutricion de la Iniciativa Salud Mesoamericana. 2015.

- 92. Zaleca sie wydanie pisemnego wyniku co najmniej trzech badan ultrasonograficznych (miedzy 11–14., 18–24. i 28–32. tygodniem ciazy). (Document title: Guidance over recommendations of ultrasonography division of the Polish Gynaecological Association)

- 93. Rivera JA, Martorell R, González W, Lutter C, González de Cossío T, Flores‐Ayala R, et al. Prevención de la desnutrición de la madre y el niño: el componente de nutrición de la Iniciativa Salud Mesoamérica 2015. Salud pública Méx [online] 2011:53 (Suppl 3):s303–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Trombofilia y embarazo. Pautas de diagnóstico y tratamiento. Rev Med Urug 2011;27:236–64. [Google Scholar]

- 95. Bernloehr A, Smith P, Vydelingum V. Antenatal care in the European Union: a survey on guidelines in all 25 member states of the Community. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2005;122:22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Piso B, Reinsperger I, Winkler R. Recommendations from international clinical guidelines for routine antenatal infection screening: does evidence matter? Int J Evid Based Healthc 2014;12:50–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. US National Library of Medicine. [www.nlm.nih.gov/services/guidelinesearch.html]. Accessed 28 May 2015.

- 98. Meats E, Brassey J, Heneghan C, Glasziou P. Using the Turning Research Into Practice (TRIP) database: how do clinicians really search? J Med Libr Assoc 2007;95:156–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting, and evaluation in health care. Prev Med 2010;51:421–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Shekelle PG, Ortiz E, Rhodes S, Morton SC, Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM, et al. Validity of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality clinical practice guidelines: how quickly do guidelines become outdated? JAMA 2001;286:1461–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. The World Bank. Data & Statistics: Country Groups [http://econ.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/DATASTATISTICS/0,contentMDK:20421402~menuPK:64133156~pagePK:64133150~piPK:64133175~theSitePK:239419,00.html].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Interventions with recommendations in opposite directions among different guidelines.