Abstract

Objective

To assess women’s behaviours and attitudes regarding the treatment of menopausal symptoms in five European countries.

Study design

Women aged ≥45 years in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom participated in an internet survey. Completers were those who reported menopausal symptoms and had treated their symptoms. Women were equally stratified by age (45–54 years, 55–64 years, ≥65 years).

Main outcome measures

Behaviours, attitudes, and experiences regarding treatment of menopausal symptoms.

Results

Of 3890 peri- to postmenopausal women screened, 67% experienced symptoms and 54% sought either medical input or some treatment concerning their symptoms. Hot flushes, the most common symptom, decreased with age but remained prevalent after age 64. Roughly 75% of women who sought relief consulted a physician, mostly a gynaecologist or a general practitioner (GP) as in the United Kingdom. The decision to seek treatment was influenced by age, number, and severity of symptoms. Approximately 79% visiting a physician received prescription therapy. Of the women who received non-hormone therapy (HT) treatment instead of HT: patients refused HT (20–44%), physicians did not discuss HT (32–46%), or advised against HT (24–43%). Women in the United Kingdom were most familiar with and favorable to HT. Interest in a new HT (34–50%) was higher than use (19–28%).

Conclusions

Menopausal symptoms are common, persistent, and bothersome, but many fail to seek treatment. Sources and types of treatment vary among age groups and countries. Education regarding women’s attitudes toward treatment should be provided to those physicians who treat menopausal symptoms in each country.

Keywords: Attitude, hormone therapy, menopause, survey, vasomotor symptoms

Introduction

Menopausal symptoms are common and bothersome to many women, yet often go untreated. In surveys of postmenopausal European women, up to 90% reported having experienced symptoms at some point during the menopausal transition,1–3 with approximately half of them considering their symptoms bothersome.1,4 Yet, the majority do not seek medical consultation.5,6 Vasomotor symptoms (VMS; hot flushes and night sweats) are the most commonly reported symptoms among European postmenopausal women.2,3,7,8 A survey of postmenopausal German women aged 45 to 60 years reported that 71.2% experienced VMS, 68.5% had sleep disturbances, 62.7% experienced irritability, and 62.5% reported physical and mental exhaustion.2 In international surveys of postmenopausal women, up to 74% experienced vaginal discomfort or dryness.5,9–11

Women avoid treatment of menopausal symptoms for a variety of reasons including discomfort with discussing vaginal symptoms5 and, commonly, safety concerns regarding hormone therapy (HT).11–14 Negative impressions of HT generally stem from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study in the United States,15 and from the Million Women Study in the United Kingdom (UK).16 The use of HT for the treatment of menopausal symptoms was widespread in the 1990s, but abruptly plummeted globally following the release of these study data.17–22 Rates of HT prescriptions remain low despite new analyses and data suggesting that factors such as age at start of treatment,23–25 time since menopause,23,25 and pre-existing health status25,26 may limit the broad applicability of the these reported results. Additionally, the WHI trial only tested conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) and medroxyprogesterone (MPA) formulations.15 Current consensus recommendations include HT as an option for many women, and state that treatment decisions for menopausal symptoms should be individualized based on an analysis of each patient’s health status, age, symptoms, and personal preference.27,28

Women’s attitudes remain mixed. In an online survey from a British menopause-focused website, 70% of 1464 respondents were in favor of HT, and 40% believed that the risks of HT had been exaggerated in the media. On the other hand, 41% of perimenopausal women reported that they would never use HT, and 77% said they would try alternative therapies before taking HT.29

The objective of this study was to assess by survey the prevalence and types of symptoms associated with menopause and behaviours toward seeking treatment in women from five European countries.

Methods

An internet survey assessing menopausal symptoms, and behaviours and attitudes toward treatment in women in five major European countries (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK) was conducted by an independent market research organization (AX’s Consulting, SPRL, Belgium, and fielded by Lightspeed GMI, the Netherlands) in July 2014. A total of 25,147 invitations to participate in the survey were extended to nationally representative panels of consumers to achieve the target sample. Peri- to postmenopausal women over the age of 45 years living in one of the five target countries at the time of the survey were eligible to complete a screening questionnaire consisting of eight questions. Because participants were not identified, they were not asked to provide written informed consent.

Women who had ever had symptoms related to menopause were qualified to complete additional questions in the main survey, answering questions addressing the types and severity of symptoms and their patterns of health care. Only women who stated that they had sought some treatment to address their symptoms were asked to complete the entire main survey of 15 questions.

Main survey questions addressed the types of symptoms women experienced, how bothered women were by their symptoms, and the actions women took to manage the symptoms. Symptom management questions included information about the length of time elapsed before treatment was sought, who women consulted for treatment, the recommendations they received, the types of products used, duration and compliance of product use, effectiveness of symptom relief, and satisfaction with treatment. Hormone therapy was described as “hormone therapy, available only on prescription” and respondents were subsequently offered the choice between various combinations of estrogen, progesterone/progestin, and testosterone; types of administration included oral tablets, transdermal gel, transdermal patch, vaginal, or pellet. Women were also asked about their level of agreement with statements regarding their attitudes about menopausal symptoms, hormone therapy products, and sources of advice on available treatments.

The sample completing the full survey was equally stratified by the age groups of 45 to 54 years, 55 to 64 years, and ≥65 years. The survey allowed qualified women in each age group to continue to enroll until the target number of participants was reached. The ≥65 age group in Spain did not reach the target sample size, and therefore could not be used for comparisons with other countries, although the data are presented.

The survey was translated by native speakers to French, German, Italian, and Spanish and verified by a translation professional. The translations were entered on a translation matrix, transferred to the survey platform and administered in the language of the country concerned.

Results

Respondent disposition and demographics

Of the 25,147 women invited to participate in the survey, a total of 3890 postmenopausal women were willing to be screened and were qualified for the survey across the five countries. Sixty-seven percent (2610/3890) of these women had experienced symptoms related to menopause. Fifty-four percent of symptomatic women (1401/2610) had sought some treatment to address their menopausal symptoms and completed the full survey, answering all questions regarding treatment (Table 1). Demographic data for the women who had ever experienced symptoms (n=2610) are reported in Table 2.

Table 1.

Disposition of survey respondents.

| France | Germany | Italy | Spain | UK | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total menopausal population screened (n=3890) | 1213 | 1119 | 547 | 452 | 559 |

| Total menopausal women with symptoms related to menopause (n=2610) | 727 | 765 | 383 | 314 | 421 |

| Women completing full surveya(n=1401) | 413 | 411 | 210 | 157 | 210 |

Equally stratified by age group: 45–54; 55–64; ≥65 (≥65 population in Spain is underrepresented, making comparisons with other countries difficult).

Table 2.

Demographics of women with menopausal symptoms (n=2610).

| France | Germany | Italy | Spain | UK | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 727 | 765 | 383 | 314 | 421 |

| Age (years; %) | |||||

| 45–54 | 35 | 37 | 26 | 40 | 38 |

| 55–64 | 36 | 32 | 36 | 49 | 32 |

| ≥65 | 29 | 30 | 38 | 11 | 29 |

| Employed (%) | 41 | 48 | 37 | 46 | 41 |

| Monthly income (%) | |||||

| Low | 12 | 21 | 26 | 28 | 20 |

| Medium (€1250–3000) | 52 | 56 | 56 | 52 | 51 |

| High | 36 | 23 | 18 | 19 | 29 |

| Education (%) | |||||

| Basic | 17 | 67 | 19 | 16 | 13 |

| Medium (up to high school) | 47 | 12 | 62 | 45 | 48 |

| Advanced | 36 | 21 | 19 | 39 | 39 |

Symptom prevalence

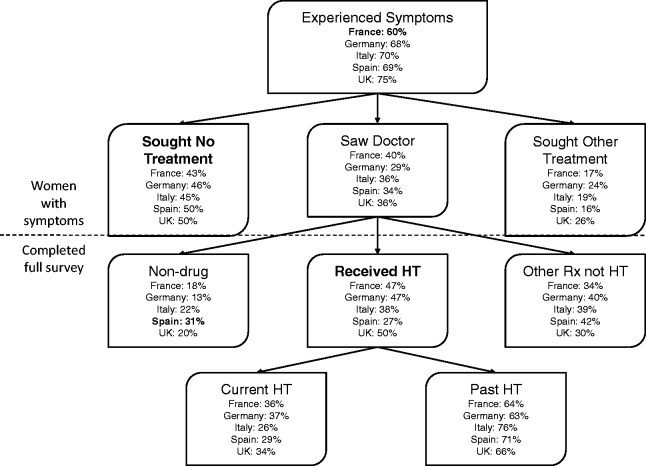

The overall prevalence of current or past menopausal symptoms for all five countries in the survey was 67% (2610/3890). Up to 75% of respondents across four of the countries currently had or had in the past experienced menopausal symptoms, with a numerically lower prevalence in France (60%; Figure 1). Of the women who had ever experienced menopausal symptoms, hot flushes were the most frequently reported symptom, at roughly 85% in all five countries (82% to 89%). With the exception of women in the UK, the prevalence of night sweats was similar among the countries (57% to 67%); in the UK, the incidence was higher, with 75% reporting night sweats. Sleep disturbances were reported by 54% to 65% of women in the five countries, vaginal dryness was experienced by 32% to 45%, and sexual dysfunction was reported by 13% to 24%.

Figure 1.

Percentage of women with menopausal symptoms, the treatments sought for their menopausal symptoms, and treatment types. Outliers and treatments of particular interest are defined in bold lettering.

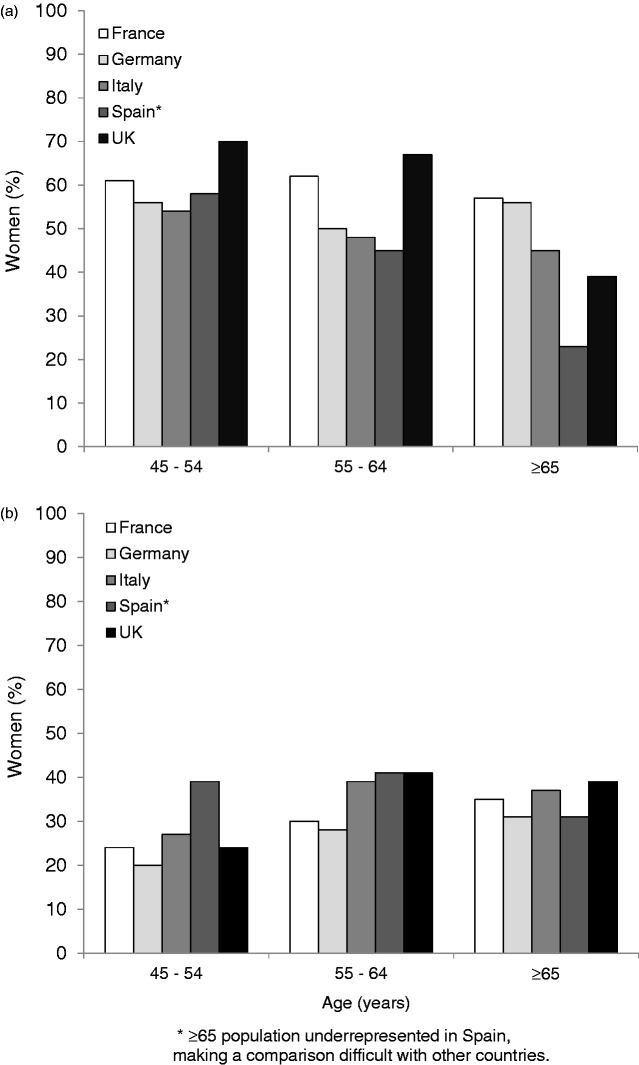

In terms of women’s current experience of menopausal symptoms, the prevalence of hot flushes showed an overall trend of diminishing with age; however, women in France exhibited a higher prevalence of hot flushes at ages 55 to 64 years compared with ages 45 to 54 years (Figure 2(a)). Hot flushes remained relatively prevalent after 64 years of age, especially in Germany (56%) and France (57%; Figure 2(a)). Women aged 45 to 54 years from the UK reported the highest current incidence of hot flushes (70%; Figure 2(a)). Night sweats decreased with age in all countries, with women in the UK reporting the highest prevalence of night sweats within each age group (67%, 62%, and 44% for age groups 45 to 54 years, 55 to 64 years, and ≥65 years, respectively vs. 42% to 67%, 35% to 46%, and 10% to 40% for the other four countries). Vaginal dryness increased with advancing age in women from all countries, except for women in the UK aged ≥65 years, who had a slightly lower prevalence (39%) than women aged 55 to 64 years (41%; Figure 2(b)).

Figure 2.

Proportion of women with menopausal symptoms who were currently experiencing (a) hot flushes or (b) vaginal dryness at the time of the survey.

The majority of women found their vaginal symptoms bothersome, regardless of age, except in Italy, where on average less than half of the women found their symptoms bothersome (data not shown).

Women reported experiencing multiple types of menopausal symptoms, with women from France and Germany reporting an average of 3.6 symptoms from age 45 to 54 years, 3.9 symptoms between ages 55 and 64 years, and 3.6 symptoms after 64 years of age. Women from Spain and the UK reported more symptoms at younger ages and fewer symptoms at older ages, with Spanish women reporting 3.9, 3.8, and 2.9 symptoms at age groups 45 to 54 years, 55 to 64 years, and over 64 years, and 4.1, 4.3, and 3.5 symptoms for the same age groups in the UK. Women from Italy reported 3.5 symptoms at age groups 45 to 54 years and 55 to 64 years, and 3.4 symptoms at ≥64 years.

Treatment trends

The majority of women reported visiting their gynaecologist at least every 2 years (in the UK the GP fulfills this role; data not shown). Roughly half (50–57%) of symptomatic women sought some type of intervention (saw a doctor or bought herbal remedies, vitamins or other supplements from the pharmacy, health store or supermarket) for treating their menopausal symptoms (Figure 1). Of women who decided to seek relief, approximately 75% consulted a physician. Women in the UK mainly saw a GP (64% vs. 11% seeing a gynaecologist), while women from the other four countries generally saw a gynaecologist (57% to 62% vs. 16% to 36% visiting a GP).

Fewer younger women with symptoms (<55 years) sought help in France (51%), Germany (48%), and the UK (44%) than older women (≥65 years; 73%, 60%, and 54%, respectively). In Italy the trend was reversed, with 59% of younger women seeking help vs. 54% of those over 64 years of age. The data for Spain indicate a trend similar to Italy, but comparisons are difficult due to the small sample size of the older age group. Within each country, women who sought help for symptom treatment (saw a doctor, visited a pharmacy, etc.) had a greater average number of symptoms than women who did not, especially in the UK, where women seeking treatment had an average of 1.1 more symptoms than those who did not seek treatment. In the other four countries, the difference in symptom number for those seeking and not seeking treatment ranged from 0.5 to 0.7. Overall, the majority of women did not seek any treatment for their menopausal symptoms until symptom severity reached an extremely bothersome level (5 points on a 5-point severity scale from not at all bothersome to extremely bothersome). Among women with hot flushes, 20% sought treatment when symptoms were “somewhat bothersome” (3 points on the severity scale), but 40% sought treatment when symptoms were “extremely bothersome”.

Women in the UK who were prescribed some form of treatment for their symptoms by their GP remained on the treatment for more than a year and continued treatment for an average of 6.51 years (median 2 years; range: 1 month to >10 years), with 77% reporting that they never or rarely missed a dose. Women in the other four countries who were prescribed treatment by their gynaecologist also had good compliance, with 71% of the women in France, 67% in Germany, 60% in Italy, and 65% in Spain reporting that they never or rarely missed a dose. However, 15% of the German women and 20% of the Italian women reported that they regularly or very regularly missed a dose.

Sixty-two percent of women in the UK reported good treatment relief (rated 4 or 5 on a 5-point scale from “treatment does/did not relieve my symptoms at all” to “treatment does/did relieve my symptoms entirely”), and 58% were somewhat to very satisfied with the treatment prescribed by their GP. The majority of women in France (67%), Germany (62%), and Italy (61%) reported good symptom relief from treatment prescribed by their gynaecologist, but only 47% in Spain stated that the treatment prescribed by a gynaecologist relieved their symptoms. Women in Spain also reported the lowest satisfaction with the treatment prescribed by their gynaecologist (22%), while 60% in France, 58% in Germany, and 48% in Italy were satisfied.

In general, symptom relief was best with HT, less effective with other therapies (including prescription and nonprescription therapies other than HT such as antidepressants, sleeping pills, phyto-estrogens, herbal treatments, homeopathic treatments, vitamins or food supplements, or over-the-counter (OTC) gels or creams), and worst with nondrug treatments (i.e. lifestyle changes; Table 3). Satisfaction was highest with HT. More than half of women taking HT were satisfied with their treatment, except in Spain (Table 3). Generally, symptom relief was higher than satisfaction, but German women reported relatively high satisfaction despite low symptom relief with their treatments (Table 3).

Table 3.

Percent of women who achieved symptom relief from the treatment received from their physician, and percent of women who were satisfied with the treatment (% relieved/% satisfied).

| France |

Germany |

Italy |

Spain |

UK |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relieved/Satisfied | |||||

| HT | 73/68 | 32/66 | 68/52 | 67/26 | 72/60 |

| Other therapies | 61/53 | 14/52 | 56/44 | 45/20 | 52/63 |

| Nondrug treatments | 56/44 | 10/34 | 48/41 | 32/32 | 50/46 |

Aspects of HT

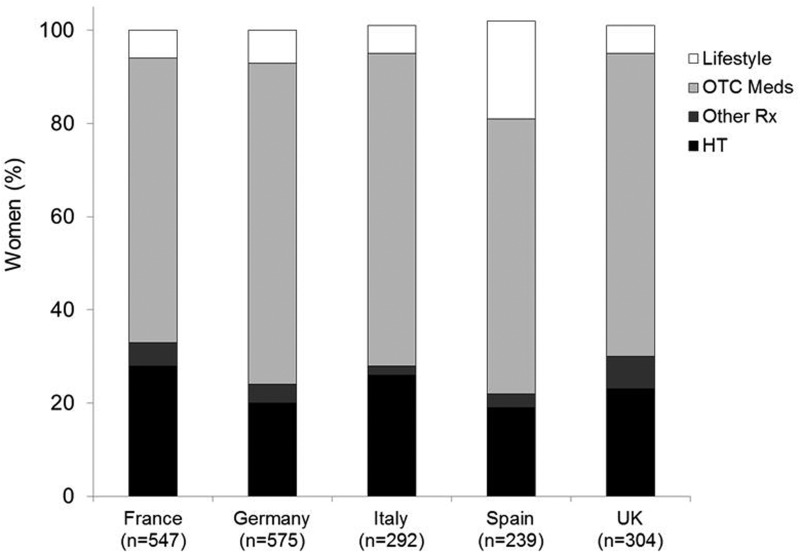

Of the symptomatic women who visited a physician (29–40%), approximately 80% received either HT or another prescription treatment in Germany, France, UK, and Italy (Figure 1). The majority of women in all countries treated their menopausal symptoms with an OTC medication at some point (Figure 3). In Germany and Spain, prescription treatment represented up to 24% of prescribed/bought treatments and was approximately 30% in the other countries (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Types of treatments women use to treat their menopausal symptoms.

With the exception of Spain and Italy, HT was more commonly prescribed to women 55 years and older than to women under 55 years of age. In France, 34% of women 45 to 54 years were prescribed HT vs. 52% and 55% for the age groups 55 to 64 and ≥65, respectively. Germany and the UK showed trends similar to France, with 30%, 48%, and 59% of German women in the age groups 45 to 54, 55 to 64, and ≥65, respectively, prescribed HT, and in the UK, 38%, 49%, and 62% respectively. In Italy, the percentage of women prescribed HT was the same in the age groups 45 to 54 years and 55 to 64 years (35%), but increased to 43% after 64 years of age. HT use was similar among all age groups in Spain (24 to 29%). The use of non-HT prescription and nonprescription therapies decreased between the ages of 45 to 54 and 55 to 64 and again after age 64 in France, Germany, and the UK; however, their use increased with age in Spain. In Italy, use peaked at age 55 to 64 before dropping again after age 64 years. The use of nondrug therapies declined with age in all countries except Italy and France, where use declined at age 55 to 64 before increasing again after age 64 years.

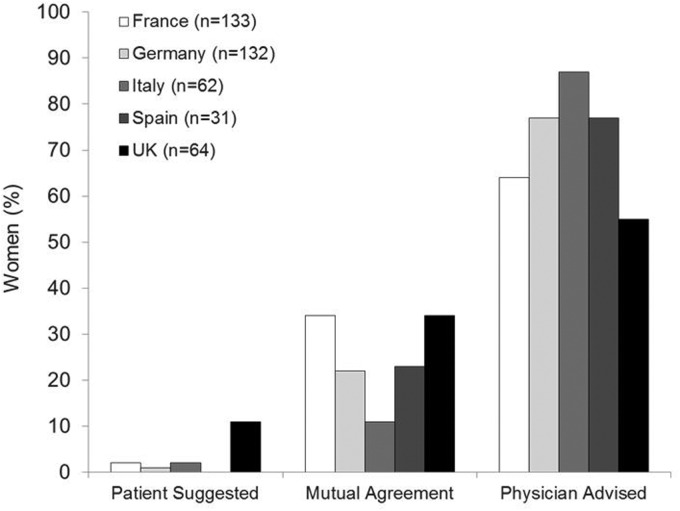

HT was prescribed the most at the initiative of the doctor and the least by patient suggestion in all 5 countries (Figure 4). Women in France and the UK reported the highest percentage of mutual agreement with their physician regarding HT use (Figure 4). Of the women who saw a physician, some did not receive HT because the physician advised against its use, the patient refused it, or the option was not discussed. Forty-four percent of German women who saw a doctor did not receive HT because they refused it themselves (vs. ∼20% in other countries). In Spain, the option of HT was more often not raised than in the other countries (46% vs. 32% to 38%).

Figure 4.

HT prescribing decision drivers (for women receiving HT treatment from a physician).

The percentage of women who were familiar with and favorable toward HT differed among countries and with the type of treatment women were currently using (HT, other therapies, or nondrug therapies). In general, women who were taking HT were more familiar with and had a more favorable impression of HT than those taking other therapies for their menopausal symptoms. Women in the UK were the most familiar with and had a more favorable impression of HT than women in other countries, regardless of their current therapy, but particularly if they were currently taking HT (51% familiar with; 66% favorable to HT). Those using HT in France, Germany, Italy, and Spain were somewhat favorable toward HT (40% to 56%). Women in France, Germany, Italy, and Spain who were using therapies other than HT were the least favorable toward HT, ranging from 21% to 28%. Familiarity of HT in France, Germany, Italy, and Spain ranged from 11% (Spanish women using nondrug therapies) to 41% (French women using HT).

A high proportion of women in France (51%) and Spain (45%) agreed with the statement, “Hormones are dangerous” (i.e. responded with “entirely agree” or “somewhat agree” on a 5-point scale), while only 21% in the UK agreed. Thirty-nine percent in Italy and 37% in Germany agreed.

When asked about their preference to take “a new prescription hormone therapy that was approved by national health authorities, proven to be safe and effective, prescribed by a physician, and containing hormones identical to those in a woman’s body”, women in Spain, the UK, and Italy were the most positive, with 50%, 48%, and 44%, respectively, willing to suggest that their doctor prescribe it or to take it if their physician recommended it. Women in Germany (34%) and in France (39%) were the least likely to take the new therapy or suggest a prescription.

Discussion

The results of this survey report that across five European countries, the majority of women surveyed in all age groups experience multiple types of bothersome symptoms associated with menopause, but fewer than half of those with symptoms seek medical help, and fewer still (9–19% of symptomatic women) receive prescription HT.

Hot flushes were the most commonly experienced symptom in women across all five countries, and remained prevalent in older aged women. Women reported experiencing 3 to 4 symptoms simultaneously across all age groups, but did not typically seek treatment unless they experienced multiple symptoms or symptoms were severe. Treatment compliance, satisfaction, and symptom relief were generally good, but varied among countries. Those who received HT generally did so at the advice of their physician.

Differences among countries in menopausal symptom prevalence and severity have been reported in other international studies.5,10,30–32 Nappi and Nijland31 surveyed postmenopausal women from 4 of the 5 countries studied here, with the exception of Spain, and the addition of The Netherlands and Switzerland, regarding their menopausal symptoms. Women in the UK showed differences from the other countries in a number of factors, such as a higher incidence of 8 out of 10 menopausal symptoms evaluated and the highest rate of treatment with HT.31 Likewise, in the European Menopause Survey 2005, postmenopausal women from the UK reported a higher prevalence of 8 out of 9 menopausal symptoms evaluated than women in 6 other European countries.33 Similarly, in our study, women from the UK reported the highest prevalence of menopausal symptoms and the highest rate of treatment with HT.

The influence of cultural factors in terms of ethnic background within a single country on the experience of menopausal symptoms was demonstrated in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), which compared menopausal symptoms in women from five ethnic groups in the United States.34 Japanese and Chinese women generally reported menopausal symptoms less frequently than women from other ethnic groups, while African-American and Hispanic women reported a number of symptoms more frequently than non-Hispanic Caucasian women.34 Differences in menopausal symptoms among women from different ethnic groups have also been observed in Colombia,35 and among women from 9 ethnic groups in 11 Asian countries.32

Although VMS decreased in general with age in this survey, 39% to 57% of women continued to experience hot flushes after 64 years of age (Spain excluded due to small sample size). Recent research has reported longer durations of VMS than has been previously assumed. In a British survey, 54% of women aged 54 to 65 years were currently experiencing hot flushes.1 Another study showed that more than 15% of women aged 55 to 59 years and 6.5% of women aged 60 to 65 years experienced VMS within the last month.36 Postmenopausal women (n=182) who reported moderate-to-severe hot flushes in the Penn Ovarian Aging Study reported a total mean duration of 10.2 years for any hot flushes, and 8.8 years for moderate-to-severe hot flushes.37 In the SWAN study, VMS persisted for more than 11 years in women who began experiencing VMS early in their menopausal transition.38

A longer duration of symptoms has implications for the duration of their treatment. The International Menopause Society (IMS) reports that HT is the most effective therapy for VMS, but is cautious about its use in women over 60 years of age or beyond 10 years past menopause.27 The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) concurs, but recognizes that moderate-to-severe VMS may persist in women over 65 years of age and has recently released a statement that HT use in women beyond age 60 is acceptable under individualized treatment conditions.39

Of those who sought treatment, most consulted with a physician at some point. For those who saw a physician, the majority received prescription treatment (both HT and non-HT). Rates of prescribing of HT can depend on type of doctor (i.e. gynaecologist or GP) and the work sector association of the doctor (i.e. public or private).40 Women from the UK tended to see a GP rather than a gynaecologist for their menopausal symptoms, and were the most familiar with and favorable to HT regardless of their current treatment.

Although health care systems among European countries are converging in recent years, differences in national health care systems that could affect how women manage their menopausal symptoms are still apparent.41 England, Italy, and Spain are among those European countries that have a full gate-keeping system in place, requiring patients to register with a GP and to obtain any necessary specialist referrals from the GP.41,42 However, in Spain access to an OB/GYN does not require a referral,42 and in Italy, women often privately pay to directly access gynaecologists.43 In France and Germany, while financial incentives encourage patients to obtain specialist referrals through a GP,41 women do have direct access to OB/GYNs.42 Germans, with few exceptions, have direct access to most physicians,42 and as of 2009, only 8% of Germans used a GP as a gate-keeper.41 Nurses are becoming more prominent in primary care in the UK, where they can lead clinics, attend patients and prescribe drugs.41 Increasingly in the UK, nurses are working as independent practitioners.44 In addition to the influence of health care systems, treatment decisions might also be influenced by regional biases in research trends such as the focus on transdermal delivery of estrogen and a preference for micronized progesterone over other progestogens in France.45–47

For those taking HT, physicians were commonly the initiator for suggesting HT. Or in the case of France, HT was prescribed in mutual agreement between physician and the woman, but for non-HT users, physicians commonly advised against HT or did not bring it up. Country of residence has been shown to be more important than physician specialty, gender, or year of graduation from medical school in determining prescribing practices for HT,48 which in turn might be expected to influence the amount and type of information physicians convey to women making treatment decisions. Lack of information about available prescription treatment options and the risks and benefits associated with those treatments may deter women from seeking treatment until symptoms become numerous or symptom severity becomes extreme. Women’s interest in a new HT was relatively high, at 34–50%, which is higher than the current rate of use. More balanced information regarding HT may help those women in need of treatment but who fail to receive treatment for their symptoms.

HT was rated as more effective at relieving menopausal symptoms than non-HT treatments in this and previous studies.2 In general, younger women used non-HT options more commonly than older women, however, this is the population at greatest need with the least risk. Younger women also claim to be less familiar with HT than older women and may be lacking information on this group of products. Along with higher ratings of symptom relief for HT compared with other treatments, women in this survey also reported higher satisfaction with HT compared with other therapies. Nondrug treatments may be effective for mild symptoms but less so for moderate-to-severe symptoms.2

In this survey, the incidence of vaginal dryness increased with age, as has been found in other studies.49 The IMS and the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) recognize that local, low-dose estrogen therapies are an effective treatment for vaginal symptoms with minimal risks.27,28,50 However, more than half of women over the age of 64 were not treating their symptoms. Lack of information may be a factor affecting women’s lack of treatment of their vaginal dryness.51 Additionally, in an international survey, 77% of participants felt that women are not comfortable discussing vaginal issues, and 60% said that women would be too embarrassed to talk to their physicians about vaginal discomfort.5 In a survey of Italian women aged 45 to 64 years, 53% had received information about menopause. Of those, 72% received information from the media, 69% from health care professionals, and 59% from friends or relatives.51 Only 39% of the women received information about HT, and almost 75% of the women interviewed would have liked to receive more information about health risks associated with menopausal treatments.5

There is a need for an FDA-/European Medicines Agency (EMA)-approved natural option for women to treat their menopausal symptoms. Natural hormones, such as 17β-estradiol and progesterone, are those that have a similar molecular structure to endogenous hormones.28,52,53 Since the aftermath of the WHI, women have sought alternative options to treat their menopausal symptoms, with many in the United States turning to non-FDA-approved compounded hormones54 and European women using complementary alternative medicine (CAM).2 Women in this survey were fairly willing (34% to 50%) to accept a new prescription hormone therapy that was described as “containing hormones identical to those in a woman’s body”.

This report has limitations as with all surveys. Although a national population was sought, the population of surveyed women may not be representative of the national population in each country. Respondents were recruited from a nationally representative panel of consumers, not a random sample of each country’s population. The low response rate for Spanish women over 64 years of age reporting symptoms reduced the percentage of women in that group, decreasing the strength of comparisons across countries for that group. Lastly, the survey did not include questions regarding some demographics or behaviours that might have affected women’s experience of menopausal symptoms, and even if much care was taken to limit any bias, the wording of questions may have influenced women’s responses.

Conclusions

Women in the five countries surveyed commonly suffer from persistent, bothersome menopausal symptoms, but many fail to seek treatment. Symptom severity, number of symptoms, and women’s age were associated with the decision to seek help to relieve symptoms. Sources and types of treatment vary among age groups and countries, as do attitudes regarding HT. Education regarding women’s fears, misconceptions, and resulting hesitation to seek treatment for menopausal symptoms, as well as current data on HT risks and benefits, should be provided to gynaecologists and GPs alike, depending on the type of physician that women primarily consult for their menopausal symptoms in each country.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Jolene Mason, PhD of Precise Publications, LLC for her assistance in the writing of this manuscript.

Declaration of conflicting interests

GC consults to pharmaceutical companies including but not limited to TherapeuticsMD. SG, BB, MK, and SM are employees of TherapeuticsMD. HC has received speaker fees and educational grants from pharmaceutical and nonpharmaceutical companies which support Menopause Matters Ltd.

Funding

TherapeuticsMD supported the survey and medical writing assistance provided by Jolene Mason, PhD (Precise Publications, LLC).

Ethical approval

The participants were obtained through an IRB-approved panel source.

Guarantor

GC.

Contributorship

GC, SG, BB, and SM provided content development and data interpretation. CC was involved in survey development, participant recruitment, and data acquisition and analysis. MK was involved in survey development, data interpretation. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hunter MS, Gentry-Maharaj A, Ryan A, et al. Prevalence, frequency and problem rating of hot flushes persist in older postmenopausal women: Impact of age, body mass index, hysterectomy, hormone therapy use, lifestyle and mood in a cross-sectional cohort study of 10,418 British women aged 54–65. BJOG 2012; 119: 40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buhling KJ, Daniels BV, Studnitz FS, et al. The use of complementary and alternative medicine by women transitioning through menopause in Germany: Results of a survey of women aged 45–60 years. Complement Ther Med 2014; 22: 94–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garton M, Reid D, Rennie E. The climacteric, osteoporosis and hormone replacement; views of women aged 45-49. Maturitas 1995; 21: 7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Geelen JM, van de Weijer PH, Arnolds HT. Urogenital symptoms and resulting discomfort in non-institutionalized Dutch women aged 50–75 years. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2000; 11: 9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nappi RE, Kokot-Kierepa M. Women’s voices in the menopause: Results from an international survey on vaginal atrophy. Maturitas 2010; 67: 233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cardini F, Lesi G, Lombardo F, et al. The use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine by women experiencing menopausal symptoms in Bologna. BMC Womens Health 2010; 10: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKinlay SM, Jefferys M. The menopausal syndrome. Br J Prev Social Med 1974; 28: 115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castelo-Branco C, Peralta S, Ferrer J, et al. The dilemma of menopause and hormone replacement–a challenge for women and health-care providers: Knowledge of menopause and hormone therapy in Spanish menopausal women. Climacteric 2006; 9: 380–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stenberg A, Heimer G, Ulmsten U, et al. Prevalence of genitourinary and other climacteric symptoms in 61-year-old women. Maturitas 1996; 24: 31–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nappi RE, Mattsson LA, Lachowsky M, et al. The CLOSER survey: Impact of postmenopausal vaginal discomfort on relationships between women and their partners in Northern and Southern Europe. Maturitas 2013; 75: 373–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simon JA, Kokot-Kierepa M, Goldstein J, et al. Vaginal health in the United States: Results from the Vaginal Health: Insights, Views & Attitudes survey. Menopause 2013; 20: 1043–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kingsberg SA, Wysocki S, Magnus L, et al. Vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: Findings from the REVIVE (REal Women’s VIews of Treatment Options for Menopausal Vaginal ChangEs) survey. J Sex Med 2013; 10: 1790–1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santoro N, Komi J. Prevalence and impact of vaginal symptoms among postmenopausal women. J Sex Med 2009; 6: 2133–2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castelo-Branco C, Ferrer J, Palacios S, et al. Spanish post-menopausal women's viewpoints on hormone therapy. Maturitas 2007; 56: 420–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: Principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002; 288: 321–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Million Women Study Collaborators. Breast cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. Lancet 2003; 362: 419–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jewett PI, Gangnon RE, Trentham-Dietz A, et al. Trends of postmenopausal estrogen plus progestin prevalence in the United States between 1970 and 2010. Obstet Gynecol 2014; 124: 727–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gayet-Ageron A, Amamra N, Ringa V, et al. Estimated numbers of postmenopausal women treated by hormone therapy in France. Maturitas 2005; 52: 296–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacLennan AH, Gill TK, Broadbent JL, et al. Continuing decline in hormone therapy use: Population trends over 17 years. Climacteric 2009; 12: 122–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menon U, Burnell M, Sharma A, et al. Decline in use of hormone therapy among postmenopausal women in the United Kingdom. Menopause 2007; 14: 462–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffmann M, Hammar M, Kjellgren KI, et al. Changes in women's attitudes towards and use of hormone therapy after HERS and WHI. Maturitas 2005; 52: 11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ameye L, Antoine C, Paesmans M, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy use in 17 European countries during the last decade. Maturitas 2014; 79: 287–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rossouw JE, Prentice RL, Manson JE, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease by age and years since menopause. JAMA 2007; 297: 1465–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schierbeck LL, Rejnmark L, Tofteng CL, et al. Effect of hormone replacement therapy on cardiovascular events in recently postmenopausal women: Randomised trial. BMJ 2012; 345: e6409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hodis HN, Mack WJ. Hormone replacement therapy and the association with coronary heart disease and overall mortality: Clinical application of the timing hypothesis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2014; 142: 68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hulley S, Grady D, Bush T, et al. Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group. JAMA 1998; 280: 605–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Villiers TJ, Pines A, Panay N, et al. Updated 2013 International Menopause Society recommendations on menopausal hormone therapy and preventive strategies for midlife health. Climacteric 2013; 16: 316–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.North American Menopause Society. The 2012 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2012; 19: 257–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cumming GP, Currie H, Morris E, et al. The need to do better - Are we still letting our patients down and at what cost? Post Reprod Health 2015; 21: 56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sievert LL, Obermeyer CM, Saliba M. Symptom groupings at midlife: Cross-cultural variation and association with job, home, and life change. Menopause 2007; 14: 798–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nappi RE, Nijland EA. Women’s perception of sexuality around the menopause: Outcomes of a European telephone survey. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2008; 137: 10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haines CJ, Xing SM, Park KH, et al. Prevalence of menopausal symptoms in different ethnic groups of Asian women and responsiveness to therapy with three doses of conjugated estrogens/medroxyprogesterone acetate: the Pan-Asia menopause (PAM) study. Maturitas 2005; 52: 264–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Genazzani AR, Schneider HP, Panay N, et al. The European Menopause Survey 2005: Women’s perceptions on the menopause and postmenopausal hormone therapy. Gynecol Endocrinol 2006; 22: 369–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gold EB, Sternfeld B, Kelsey JL, et al. Relation of demographic and lifestyle factors to symptoms in a multi-racial/ethnic population of women 40–55 years of age. Am J Epidemiol 2000; 152: 463–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Monterrosa A, Blumel JE, Chedraui P. Increased menopausal symptoms among Afro-Colombian women as assessed with the Menopause Rating Scale. Maturitas 2008; 59: 182–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gartoulla P, Worsley R, Bell RJ, et al. Moderate to severe vasomotor and sexual symptoms remain problematic for women aged 60 to 65 years. Menopause 2015; 22: 694–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Sanders RJ. Risk of long-term hot flashes after natural menopause: Evidence from the Penn Ovarian Aging Study cohort. Menopause 2014; 21: 924–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Avis NE, Crawford SL, Greendale G, et al. Duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms over the menopause transition. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175: 531–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The North American Menopause Society statement on continuing use of systemic hormone therapy after age 65. Menopause 2015; 22: 693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Castelo-Branco C, Ferrer J, Palacios S, et al. The prescription of hormone replacement therapy in Spain: Differences between general practitioners and gynaecologists. Maturitas 2006; 55: 308–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Masseria C, Irwin R, Thomson S, et al. Primary care in Europe. The London School of Economics and Political Science 2009, pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kringos DS, Boerma WGW, Hutchinson A, et al. Building primary care in a changing Europe. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015, p.174. [PubMed]

- 43.Ferre F, de Belvis AG, Valerio L, et al. Italy: Health system review. Health Syst Transit 2014; 16: 1–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Health care outside hospital: Accessing generalist and specialist care in eight countries. World Health Organization. Copenhagen, Denmark. 2006. www.euro.who.int/observatory (accessed November 2015).

- 45.Fournier A, Berrino F, Clavel-Chapelon F. Unequal risks for breast cancer associated with different hormone replacement therapies: Results from the E3N cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2008; 107: 103–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Canonico M, Oger E, Plu-Bureau G, et al. Hormone therapy and venous thromboembolism among postmenopausal women: Impact of the route of estrogen administration and progestogens: The ESTHER study. Circulation 2007; 115: 840–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gompel A. Micronized progesterone and its impact on the endometrium and breast vs. progestogens. Climacteric 2012; 15: 18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sievert LL, Saliba M, Reher D, et al. The medical management of menopause: A four-country comparison care in urban areas. Maturitas 2008; 59: 7–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dennerstein L, Dudley EC, Hopper JL, et al. A prospective population-based study of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol 2000; 96: 351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Management of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy: 2013 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2013; 20: 888–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Donati S, Cotichini R, Mosconi P, et al. Menopause: Knowledge, attitude and practice among Italian women. Maturitas 2009; 63: 246–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Compounded bioidentical hormones. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 322. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2005; 106: 1139–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Conaway E. Bioidentical hormones: An evidence-based review for primary care providers. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2011; 111: 153–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pinkerton J, Santoro N. Compounded bioidentical hormone therapy: Identifying use trends and knowledge gaps among US women. Menopause 2015; 22: 926–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]