Abstract

Background

Platelet transfusions are used in modern clinical practice to prevent and treat bleeding in people with thrombocytopenia. Although considerable advances have been made in platelet transfusion therapy since the mid‐1970s, some areas continue to provoke debate especially concerning the use of prophylactic platelet transfusions for the prevention of thrombocytopenic bleeding.

Objectives

To determine whether agents that can be used as alternatives, or adjuncts, to platelet transfusions for people with haematological malignancies undergoing intensive chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation are safe and effective at preventing bleeding.

Search methods

We searched 11 bibliographic databases and four ongoing trials databases including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, 2016, Issue 4), MEDLINE (OvidSP, 1946 to 19 May 2016), Embase (OvidSP, 1974 to 19 May 2016), PubMed (e‐publications only: searched 19 May 2016), ClinicalTrials.gov, World Health Organization (WHO) ICTRP and the ISRCTN Register (searched 19 May 2016).

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials in people with haematological malignancies undergoing intensive chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation who were allocated to either an alternative to platelet transfusion (artificial platelet substitutes, platelet‐poor plasma, fibrinogen concentrate, recombinant activated factor VII, desmopressin (DDAVP), or thrombopoietin (TPO) mimetics) or a comparator (placebo, standard care or platelet transfusion). We excluded studies of antifibrinolytic drugs, as they were the focus of another review.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors screened all electronically derived citations and abstracts of papers identified by the review search strategy. Two review authors assessed risk of bias in the included studies and extracted data independently.

Main results

We identified 16 eligible trials. Four trials are ongoing and two have been completed but the results have not yet been published (trial completion dates: April 2012 to February 2017). Therefore, the review included 10 trials in eight references with 554 participants. Six trials (336 participants) only included participants with acute myeloid leukaemia undergoing intensive chemotherapy, two trials (38 participants) included participants with lymphoma undergoing intensive chemotherapy and two trials (180 participants) reported participants undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Men and women were equally well represented in the trials. The age range of participants included in the trials was from 16 years to 81 years. All trials took place in high‐income countries. The manufacturers of the agent sponsored eight trials that were under investigation, and two trials did not report their source of funding.

No trials assessed artificial platelet substitutes, fibrinogen concentrate, recombinant activated factor VII or desmopressin.

Nine trials compared a TPO mimetic to placebo or standard care; seven of these used pegylated recombinant human megakaryocyte growth and differentiation factor (PEG‐rHuMGDF) and two used recombinant human thrombopoietin (rhTPO).

One trial compared platelet‐poor plasma to platelet transfusion.

We considered that all the trials included in this review were at high risk of bias and meta‐analysis was not possible in seven trials due to problems with the way data were reported.

We are very uncertain whether TPO mimetics reduce the number of participants with any bleeding episode (odds ratio (OR) 0.40, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.10 to 1.62, one trial, 120 participants, very low quality evidence). We are very uncertain whether TPO mimetics reduce the risk of a life‐threatening bleed after 30 days (OR 1.46, 95% CI 0.06 to 33.14, three trials, 209 participants, very low quality evidence); or after 90 days (OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.06 to 16.37, one trial, 120 participants, very low quality evidence). We are very uncertain whether TPO mimetics reduce platelet transfusion requirements after 30 days (mean difference ‐3.00 units, 95% CI ‐5.39 to ‐0.61, one trial, 120 participants, very low quality evidence). No deaths occurred in either group after 30 days (one trial, 120 participants, very low quality evidence). We are very uncertain whether TPO mimetics reduce all‐cause mortality at 90 days (OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.24 to 4.20, one trial, 120 participants, very low quality evidence). No thromboembolic events occurred for participants treated with TPO mimetics or control at 30 days (two trials, 209 participants, very low quality evidence). We found no trials that looked at: number of days on which bleeding occurred, time from randomisation to first bleed or quality of life.

One trial with 18 participants compared platelet‐poor plasma transfusion with platelet transfusion. We are very uncertain whether platelet‐poor plasma reduces the number of participants with any bleeding episode (OR 16.00, 95% CI 1.32 to 194.62, one trial, 18 participants, very low quality evidence). We are very uncertain whether platelet‐poor plasma reduces the number of participants with severe or life‐threatening bleeding (OR 4.00, 95% CI 0.56 to 28.40, one trial, 18 participants, very low quality evidence). We found no trials that looked at: number of days on which bleeding occurred, time from randomisation to first bleed, number of platelet transfusions, all‐cause mortality, thromboembolic events or quality of life.

Authors' conclusions

There is insufficient evidence to determine if platelet‐poor plasma or TPO mimetics reduce bleeding for participants with haematological malignancies undergoing intensive chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation. To detect a decrease in the proportion of participants with clinically significant bleeding from 12 in 100 to 6 in 100 would require a trial containing at least 708 participants (80% power, 5% significance). The six ongoing trials will provide additional information about the TPO mimetic comparison (424 participants) but this will still be underpowered to demonstrate this level of reduction in bleeding. None of the included or ongoing trials include children. There are no completed or ongoing trials assessing artificial platelet substitutes, fibrinogen concentrate, recombinant activated factor VII or desmopressin in people undergoing intensive chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation for haematological malignancies.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Male; Platelet Transfusion; Platelet Transfusion/statistics & numerical data; Stem Cell Transplantation; Cause of Death; Hematologic Neoplasms; Hematologic Neoplasms/drug therapy; Hemorrhage; Hemorrhage/etiology; Hemorrhage/mortality; Hemorrhage/prevention & control; Leukemia, Myeloid, Acute; Leukemia, Myeloid, Acute/drug therapy; Lymphoma; Lymphoma/drug therapy; Plasma; Polyethylene Glycols; Polyethylene Glycols/adverse effects; Polyethylene Glycols/therapeutic use; Recombinant Proteins; Recombinant Proteins/adverse effects; Recombinant Proteins/therapeutic use; Remission Induction; Thrombocytopenia; Thrombocytopenia/chemically induced; Thrombocytopenia/therapy; Thrombopoietin; Thrombopoietin/adverse effects; Thrombopoietin/therapeutic use

Plain language summary

Alternative or additional agents to platelet transfusions to prevent bleeding in people with blood cancers receiving intensive treatment

Review question

What is the best way to prevent bleeding for people being treated with intensive chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation for blood, or bone marrow cancers? Should we use platelet transfusions (the current standard treatment), or use other agents instead of (or as well as) platelet transfusions.

Background

Approximately one in eight cancers arise from the blood, bone marrow, or lymph nodes. These cancers are divided into many different types that are treated differently. Examples include acute myeloid leukaemia and lymphoma. Some of these cancers can be cured with high‐dose (intensive) chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation. These treatments destroy the cancer but can also damage the normal blood‐producing cells. One consequence of this is a reduction in the number of platelets in the blood. Platelets are essential to make the blood clot normally. Consequently, people receiving these treatments are vulnerable to bleeding until their platelets increase in number.

Platelet transfusions (taken from a blood donor) are often given to try to prevent people with blood cancer from bleeding. We do not know how well these transfused platelets work. We know that there are risks from platelet transfusion, such as transmission of infections. It is possible that there are better ways to prevent bleeding in this setting. In this review, we examined whether other agents could be used instead of (or as well as) platelet transfusion to prevent bleeding. We also assessed the risk of serious side effects, such as forming abnormal blood clots (thromboembolic events). Potential agents include artificial platelets, platelet‐poor plasma, fibrinogen concentrate, recombinant activated factor VII, desmopressin and thrombopoietin mimetics. Terms and treatments are described in the glossary in the 'Published notes' section of this review).

Study characteristics

The evidence is current to May 2016. We identified 16 clinical trials: 10 completed trials and six ongoing trials. We included the 10 completed trials in this review. Six trials included adults with acute myeloid leukaemia undergoing intensive chemotherapy, two trials included adults with lymphoma undergoing intensive chemotherapy and two trials included adults undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation. The age range of participants was between 16 and 81 years. Men and women were equally well represented. All trials took place in high‐income countries. The manufacturer of the agent that was under investigation sponsored eight trials, and two trials did not report their source of funding. We identified nine trials (536 participants) assessing thrombopoietin mimetics and one trial (18 participants) assessing platelet‐poor plasma. These trials were conducted between 1974 and 2015. No trial assessed artificial platelets, fibrinogen concentrate, recombinant activated factor VII or desmopressin).

Key results

For adults treated with thrombopoietin mimetics, we are very uncertain whether there is a difference in the number of participants with: any bleeding, risk of life‐threatening bleeding, number of platelet transfusions, overall risk of death or thromboembolic events because the quality of the evidence was very low. We found no trials of thrombopoietin mimetics that looked at: the number of days on which bleeding occurred, time from start of trial to first bleed or quality of life.

For adults treated with platelet‐poor plasma, we are very uncertain whether there is a difference in the number of participants with: any bleeding or risk of life‐threatening bleeding. We found no trials that looked at: the number of days on which bleeding occurred, time from start of trial to first bleeding episode, number of platelet transfusions, overall risk of death, thromboembolic events or quality of life.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence was very low, making it difficult to draw conclusions or make recommendations regarding the usefulness and safety of thrombopoietin mimetics or platelet‐poor plasma. There was no trial evidence for artificial platelets, fibrinogen concentrate, recombinant activated factor VII or desmopressin.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Thrombopoietin mimetics versus placebo or standard care.

| Thrombopoietin mimetics versus placebo or standard care | ||||||

| Population: people with haematological disorders undergoing intensive chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation Intervention: thrombopoietin mimetics Comparison: placebo or standard care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (trials) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo or standard care | Risk with thrombopoietin mimetics | |||||

| Number of participants with at least 1 bleeding episode follow‐up: 30 days | Trial population | OR 0.40 (0.10 to 1.62) | 120 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 1, 2 | 2 further trials reported combined results that could not be included in the analysis. 25% of participants in the combined intervention arms and 50% in combined control arms had a least 1 clinically significant bleeding episode | |

| 50 per 1000 | 21 per 1000 (5 to 79) | |||||

| Moderate** | ||||||

| 430 per 1000 | 232 per 1000 (70 to 550) | |||||

| Number of participants with severe or life‐threatening bleeding follow‐up: 30 days | Moderate** | OR 1.46 (0.06 to 33.14) | 209 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 3, 4 | No severe or life‐threatening bleeding events occurred in the control arms of these trials | |

| 3 per 1000 | 5 per 1000 (0 to 102) | |||||

| Number of days on which bleeding occurred ‐ not reported | Not estimable | Not estimable | (No trials) | ‐ | Outcome not reported | |

| Time from randomisation to first bleeding episode ‐ not reported | Not estimable | Not estimable | (No trials) | ‐ | Outcome not reported | |

| All‐cause mortality follow‐up: 30 days | Not estimable | Not estimable | 120 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 4, 5 | No deaths reported in either arm of this trial. 2 further trials reported combined results that could not be included in the analysis: all‐cause mortality 0% to 8.3% in intervention arms and 11.8% in the combined control arms | |

| Number of platelet transfusions follow‐up: 30 days | The mean number of platelet transfusions was 9 units | The mean number of platelet transfusions in the intervention group was 3 units lower (5.39 lower to 0.61 lower) | ‐ | 120 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 1, 2 | 5 other trials reported in a manner that could not be incorporated into meta‐analysis. Median platelet transfusions were 4 to 10 units in the intervention arms and 4 to 8 units in the control arms |

| Thromboembolic events follow‐up: 30 days | Not estimable | Not estimable | 209 (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 4, 5 | No thromboembolic events were reported in any arm of these trials. 5 further trials reported combined results that could not be included in the analysis: thromboembolic events 0% to 9.1% in intervention arms and 5.6% to 15.8% in the control arms | |

| Quality of life ‐ not reported | Not estimable | Not estimable | (No trials) | ‐ | Outcome not reported | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ** Background risk derived from the prophylactic transfusion arm of TOPPS trial (Stanworth 2013). CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1Downgraded one point due to imprecision (low event rate with confidence intervals including both absolute estimates of benefit and of harm).

2Downgraded two points due to risk of performance and detection bias.

3Downgraded one point rather than two points due to risk of performance and detection bias, because the outcome had already been downgraded by two points due to imprecision.

4Downgraded two points due to imprecision (low event rate with confidence intervals including both absolute estimates of benefit and of harm).

5Downgraded one point due to risk of performance bias.

Summary of findings 2. Platelet‐poor plasma.

| Platelet‐poor plasma | ||||||

| Population: people with haematological disorders undergoing intensive chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation Intervention: platelet‐poor plasma transfusion Comparison: platelet transfusion | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (trials) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with platelet transfusion | Risk with platelet‐poor plasma | |||||

| Number of participants with at least 1 bleeding episode follow‐up: 30 days |

Trial population | OR 16.00 (1.32 to 194.62) | 18 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 1, 2 | ‐ | |

| 333 per 1000 | 889 per 1000 (398 to 990) | |||||

| Moderate** | ||||||

| 430 per 1000 | 923 per 1000 (499 to 993) |

|||||

| Number of participants with severe or life‐threatening bleeding follow‐up: 30 days |

Trial population | OR 4.00 (0.56 to 28.40) |

18 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1, 2 | ‐ | |

| 333 per 1000 | 667 per 1000 (219 to 934) |

|||||

| Moderate** | ||||||

| 3 per 1000 | 13 per 1000 (2 to 88) |

|||||

| Number of days on which bleeding occurred ‐ not reported | Not estimable | Not estimable | (No trials) | ‐ | Outcome not reported | |

| Time from randomisation to first bleeding episode ‐ not reported | Not estimable | Not estimable | (No trials) | ‐ | Outcome not reported | |

| Number of platelet transfusions ‐ not reported | Not estimable | Not estimable | (No trials) | ‐ | Outcome not reported | |

| All‐cause mortality ‐ not reported | Not estimable | Not estimable | (No trials) | ‐ | Outcome not reported | |

| Thromboembolic events ‐ not reported | Not estimable | Not estimable | (No trials) | ‐ | Outcome not reported | |

| Quality of life ‐ not reported | Not estimable | Not estimable | (No trials) | ‐ | Outcome not reported | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ** Background risk derived from prophylactic transfusion arm of TOPPS trial (Stanworth 2013). CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded one point for risk of bias due to risk of performance bias.

2 Downgraded two points for imprecision (low event rate with confidence intervals including both absolute estimates of benefit and of harm).

Background

Description of the condition

Haematological malignancies account for between 8% and 9% of all new cancers reported in the UK and USA (CDC 2012; ONS 2014), and their incidence is increasing (11% to 14% increase in new cases of lymphoma and myeloma between 1991 and 2001, and 2008 and 2010) (Cancer Research UK 2013). The prevalence of these cancers is also increasing due to increased survival rates (Coleman 2004; Rachet 2009). These improved survival rates are due to the introduction of intensive chemotherapy treatments and use of stem cell transplantation (Burnett 2011; Fielding 2007; Patel 2009). Over 50,000 haematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCT) are carried out annually worldwide (Gratwohl 2010), and are used to treat both malignant and non‐malignant haematological disorders. Autologous HSCT is the most common type of HSCT (57% to 59%) (Gratwohl 2010; Passweg 2012). However, chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation can lead to prolonged periods of severe thrombocytopenia (De la Serna 2008; Heddle 2009a; Rysler 2010; Stanworth 2013; Wandt 2012).

Platelet transfusions are used in modern clinical practice to prevent and treat bleeding in people with thrombocytopenia with bone marrow failure secondary to chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation. Administration of platelet transfusions to people with haematological disorders now constitute a significant proportion (up to 67%) of all platelets issued (Cameron 2007; Greeno 2007; Pendry 2011), and the majority of these (69%) are given to prevent bleeding (Estcourt 2012a).

People can become refractory to platelet transfusions. In an analysis of the TRAP 1997 study data, there was a progressive decrease in the post‐transfusion platelet count increments and time interval between transfusions as the number of preceding transfusions increased (Slichter 2005). This effect was seen irrespective of whether or not people had developed detectable human leukocyte antigen (HLA) antibodies (Slichter 2005).

Platelet transfusions are also associated with adverse events. Mild to moderate reactions to platelet transfusions include rigors, fever and urticaria (Heddle 2009b). These reactions are not life‐threatening but can be extremely distressing for the person. Rarer, but more serious sequelae include: anaphylaxis, transfusion‐transmitted infections, transfusion‐related acute lung injury and immunomodulatory effects (Benson 2009; Blumberg 2009; Bolton‐Maggs 2012; Heddle 2009b; Knowles 2011; Pearce 2011; Popovsky 1985; Silliman 2003; Taylor 2010).

Any strategy that can safely decrease the need for prophylactic platelet transfusions in people with haematological disorders will have significant logistical and financial implications as well as decreasing peoples' exposure to the risks of transfusion.

Description of the intervention

The standard practice in most haematology units across the developed world is to use prophylactic transfusions to prevent bleeding for people with thrombocytopenia due to intensive chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation in line with guidelines (BCSH 2003; BCSH 2004; Board 2009; NBA 2012; Schiffer 2001; Slichter 2007; Tinmouth 2007). The experimental intervention is to give an alternative treatment, such as artificial platelet substitutes, platelet‐poor plasma (PPP), recombinant activated factor VII (rFVIIa), fibrinogen or TPO mimetics. This review does not include anti‐fibrinolytics (lysine analogues) because they are the focus of another Cochrane Review (Estcourt 2016).

How the intervention might work

Alternatives to platelet transfusions for decreasing the incidence of thrombocytopenic bleeding have been suggested. These include the use of artificial substitutes for platelets, treatment with pharmacological agents that act at different parts of the clotting cascade (Estcourt 2016; Mannucci 1997), and growth factor agonists to stimulate the person's bone marrow to recover more rapidly and therefore decrease the duration of thrombocytopenia (Miao 2012).

Artificial platelet substitutes

Artificial platelet substitutes overcome some of the problems associated with prophylactic platelet transfusions derived from donors (limited supply and risk of infection). Various different forms have been suggested and studied, including liposomes, nanoparticles, nanosheets and hydrogels (Doshi 2012; Nishiya 2002; Okamura 2009a; Okamura 2009b). In vitro studies and animal models have been used to assess the efficacy of these agents (Doshi 2012; Nishiya 2002; Okamura 2009a; Okamura 2009b).

Platelet‐poor plasma (PPP)

PPP is a source of clotting factor concentrates and fibrinogen (Desborough 2012).

Recombinant factor VIIa

rFVIIa is licensed for use in people with haemophilia and inhibitory allo‐antibodies, and for prophylaxis and treatment of people with congenital factor VII deficiency. It is also used for off‐license indications to prevent bleeding in operations where blood loss is likely to be high, or to stop bleeding that is proving difficult to control by other means, or both. However, one systematic review showed that the effectiveness of rFVIIa outside its licensed indications remains unproven (Simpson 2012).

Fibrinogen

Fibrinogen is the endogenous substrate for fibrin formation (Manco‐Johnson 2009). The formation of a fibrin network, formed by activated platelets and cross‐linked fibrin strings, is the endpoint of the coagulation process in vivo (Sørensen 2011). Multiple in vitro experiments, animal studies and non‐randomised clinical trials have suggested that use of a fibrinogen concentrate may be efficient and safe in controlling perioperative bleeding (Solomon 2010; Sørensen 2011).

Desmopressin

Desmopressin (DDAVP), a derivative of the antidiuretic hormone, has been used since the 1970s to treat mild haemophilia A and von Willebrand's disease without the need for blood products (Mannucci 1997). DDAVP increases the plasma levels of factor VIII (FVIII) and von Willebrand factor (vWF) and enhances platelet adhesion to the vessel wall but has no effect on the platelet count (Barnhart 1983; Mannucci 1997; Sakariassen 1984). It has been shown to be effective at preventing bleeding in people who have normal levels of FVIII and vWF, for example, people with uraemia (Mannucci 1997).

Thrombopoietin mimetics

TPO is the major regulator of both megakaryopoiesis and thrombopoiesis, it promotes cell differentiation and prevents apoptosis of megakaryocyte colony‐forming cells and early megakaryocyte progenitors (Kuter 2010). The two main TPO mimetics in current use are romiplostim (weekly injection) and eltrombopag (daily oral tablet). The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends both romiplostim and eltrombopag for use in adults with immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) who have severe disease and a high risk of bleeding (NICE 2011; NICE 2013). However, in one systematic review of TPO mimetics in chronic ITP there was no evidence to demonstrate that TPO mimetics improved significant bleeding events despite significantly increasing platelet response (Zeng 2011). PEG‐rHuMGDF is a TPO mimetic that has now been withdrawn from development after the discovery that, in some cases, both participants and normal volunteers developed antiplatelet antibodies resulting in a prolonged thrombocytopenia (Li 2001). The efficacy of recombinant human thrombopoietin (rhTPO) (daily injection) is in under investigation in China (Han 2015; Miao 2012).

Assessment of bleeding

A bleeding assessment has been seen as a more clinically relevant measure of the effect of platelet transfusions than surrogate markers such as platelet increment.

Any review that uses bleeding as a primary outcome measure needs to assess the way that the trials have recorded bleeding. Unfortunately, the way bleeding has been recorded and assessed has varied markedly between trials (Cook 2004; Estcourt 2013; Heddle 2003).

Retrospective analysis of bleeding leads to a risk of bias because bleeding events may be missed, and only more severe bleeding is likely to have been documented. Prospective bleeding assessment forms provide more information and are less likely to miss bleeding events. However, different assessors may grade the same bleed differently and it is very difficult to blind the assessor to the intervention.

The majority of trials have used the World Health Organization (WHO) system, or a modification of it, for grading bleeding (Estcourt 2013; Koreth 2004; WHO 1979). One limitation of all the scoring systems that have been based on the WHO system is that the categories are relatively broad and subjective. This means that a small change in a person's bleeding risk may not be detected. Another limitation is that the modified WHO categories are partially defined by whether a bleeding person requires a blood transfusion. The threshold for intervention may vary between clinicians and institutions and so the same level of bleeding could be graded differently in different institutions.

The definition of what constitutes clinically significant bleeding has varied between trials. Although the majority of more recent platelet transfusion trials (Heddle 2009a; Slichter 2010; Stanworth 2010; Wandt 2012) now classify it as WHO grade 2 or above, there has been greater heterogeneity in the past (Cook 2004; Estcourt 2013; Koreth 2004). The difficulties with assessing and grading bleeding may limit the ability to compare results between trials and this needs to be kept in mind when reviewing the evidence for the effectiveness of prophylactic platelet transfusions.

Why it is important to do this review

This review focused on the additional question of whether alternative agents instead of prophylactic platelet transfusions can be used for the prevention or control (or both) of life‐threatening thrombocytopenic bleeding. This review did not assess the evidence for antifibrinolytics (lysine analogues) as this is the focus of another review (Estcourt 2016).

Avoiding the need for unnecessary prophylactic platelet transfusions in people with haematological malignancies will have significant logistical and financial implications for national health services as well as decreasing people's exposure to the risks of transfusion. This knowledge is perhaps even more important in the development of platelet transfusion strategies in low and middle income countries where access to blood components is much more limited (Verma 2009).

This review did not assess whether there are any differences in the efficacy of apheresis versus whole‐blood derived platelet products, the efficacy of pathogen‐reduced platelet components, the efficacy of HLA‐matched versus random donor platelets, or differences between ABO identical and ABO non‐identical platelet transfusions. This is because these topics have been covered by other systematic reviews (Butler 2013; Heddle 2008; Pavenski 2013; Shehata 2009).

Objectives

To determine whether agents that can be used as alternatives, or adjuncts, to platelet transfusions for people with haematological malignancies undergoing intensive chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation are safe and effective at preventing bleeding.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs). We applied no restrictions on language or publication status.

Types of participants

We included people with haematological malignancies receiving treatment with intensive chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation (or both). We included participants of all ages, and included both inpatients and outpatients.

When trials consisted of mixed populations of participants (e.g. people with diagnoses of solid tumours), we used only data from the haematological subgroups. If subgroup data for haematological participants were not provided (after contacting the authors of the trial), we excluded trials if less than 80% of participants had a haematological disorder. We excluded any participants that were not treated with intensive chemotherapy or a stem cell transplant as these participants are the focus of another review (Desborough 2016). We included participants with non‐malignant haematological disorders (e.g. aplastic anaemia, congenital bone marrow failure syndromes) that were being treated with an allogeneic stem cell transplant. We also excluded people treated with non‐intensive chemotherapy (such as azacitidine, decitabine and lenalidomide) because the degree of thrombocytopenia is much less profound with a lower risk of bleeding. Trials in people with chronic bone marrow failure using these agents are reported in another review (Desborough 2016).

Types of interventions

We included the two following comparisons:

alternative agent versus prophylactic platelet transfusion;

alternative agent and prophylactic platelet transfusion versus placebo or no treatment and prophylactic platelet transfusion.

We considered the following interventions:

-

experimental intervention: alternative agents:

artificial platelet substitutes;

PPP;

rFVIIa;

fibrinogen;

TPO mimetics;

DDAVP.

We placed no restrictions on the dose of alternative agents used.

-

Comparator intervention:

comparison one: alternative agent versus prophylactic platelet transfusion. The comparator was prophylactic platelet transfusions. Transfusion of platelet concentrates, prepared either from individual units of whole blood or by apheresis, and given prophylactically to prevent bleeding. Prophylactic platelet transfusions are typically given when blood platelet counts fall below a given trigger level. There was no restriction on the dose or frequency of platelet transfusions, neither was there a restriction on the transfusion trigger level, although we took this information into account in the analysis where available;

comparison two: alternative agent and prophylactic platelet transfusion versus placebo or no treatment and prophylactic platelet transfusion. The comparator was prophylactic platelet transfusions and placebo or no treatment. There was no restriction on the dose or frequency of platelet transfusions used in addition to the alternative agents, but the dose of prophylactic platelet transfusions received and the platelet transfusion threshold at which they were given was the same in both arms of the trial.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

-

Number and severity of bleeding episodes within 30 days from the start of the trial:

Number of participants with at least one bleeding episode.

Total number of days on which bleeding occurred per participant.

Number of participants with at least one episode of severe or life‐threatening bleeding.

Time from randomisation to first bleeding episode.

Secondary outcomes

Mortality (all‐causes, secondary to bleeding and secondary to infection) within 30 days and 90 days from the start of the trial.

Overall survival within 30 days, 90 days and 180 days from the start of the trial.

Proportion of participants requiring additional interventions to stop bleeding (surgical, medical e.g. tranexamic acid, other blood products e.g. fresh frozen plasma (FFP), cryoprecipitate) within 30 days from the start of the trial.

Number of platelet transfusions per participant and number of platelet components per participant within 30 days from the start of the trial.

Platelet transfusion interval within 30 days from the start of the trial.

Duration of thrombocytopenia within 30 days from the start of the trial.

Number of red cell transfusions per participant and number of red cell components per participant within 30 days from the start of the trial.

Proportion of participants achieving complete remission within 30 days and 90 days from the start of the trial.

Total time in hospital within 30 days from the start of the trial.

Adverse effects of treatments (transfusion reactions, transfusion‐transmitted infections, thromboembolism, development of platelet antibodies, development of platelet refractoriness, drug reactions) within 30 days and 90 days from the start of the trial.

Quality of life, as defined by the individual trials.

We expressed all primary and secondary outcomes in the formats defined in the Measures of treatment effect section of this review when data were available. Quality of life used the trial's own measure as there is no definitive participant‐reported outcome measure for this participant group (Estcourt 2014a). The platelet transfusion interval was calculated in many different ways and the exact methodology was not reported sufficiently to allow us to combine the data.

Search methods for identification of studies

The Systematic Review Initiative (SRI) Information Specialist (CD) formulated entirely new search strategies for this review in collaboration with the Cochrane Haematological Malignancies Review Group.

Electronic searches

Bibliographic databases

We searched the following databases:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, 2016, Issue 4) (Appendix 1);

MEDLINE (OvidSP, 1946 to 19 May 2016) (Appendix 2);

Embase (OvidSP, 1974 to 19 May 2016) (Appendix 3);

PubMed (e‐publications only, 19 May 2016) (Appendix 4);

CINAHL (EBSCOhost, 1982 to 19 May 2016) (Appendix 5);

UKBTS/SRI Transfusion Evidence Library (www.transfusionevidencelibrary.com) (1950 to 19 May 2016) (Appendix 6);

Web of Science: Conference Proceedings Citation Index‐Science (CPCI‐S) (Thomson Reuters, 1990 to 19 May 2016) (Appendix 7);

LILACS (BIREME/PAHO/WHO, 1982 to 19 May 2016) (Appendix 8);

IndMed (ICMR‐NIC, 1985 to 19 May 2016) (Appendix 9);

KoreaMed (KAMJE, 1997 to 19 May 2016) (Appendix 10);

PakMediNet (2001 to 19 May 2016) (Appendix 10).

As we rewrote the search strategies, we ran searches from the earliest dates specified above and did not updated them from the original and updated searches in January 2002 (Stanworth 2004) and November 2011 (Estcourt 2012b). We combined searches in MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL with adaptations of the Cochrane RCT search filters, as detailed in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Lefebvre 2011).

Databases of ongoing trials

In order to identify ongoing trials to 19 May 2016, we also searched ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/search) (Appendix 11), the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry (ICTRP) (apps.who.int/trialsearch/) (Appendix 11), the ISRCTN Register (www.controlled‐trials.com/isrctn/) (Appendix 12), the EU Clinical Trials Register (www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr‐search) (Appendix 13) and the Hong Kong Clinical Trials Register (www.hkclinicaltrials.com/) (Appendix 14).

Searching other resources

Handsearching of references

We checked references of all included trials, relevant review articles and current treatment guidelines for further literature. We limited these searches to the 'first generation' reference lists.

Personal contacts

We contacted authors of relevant trials, trial groups and experts worldwide known to be active in the field for unpublished material or further information on ongoing trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We updated the selection of studies from that performed for the previous version of this review (Estcourt 2012b).

Two review authors (MD, LE) independently performed an initial screen of all electronically derived citations and abstracts of papers identified by the review search strategy for relevance. We excluded clearly irrelevant trials at this stage.

Two review authors (MD, LE) independently assessed the full texts of all potentially relevant trials formally for eligibility against the criteria. We resolved all disagreements by discussion with a third review author (SS). We sought further information from trial authors if the article contained insufficient data to make a decision about eligibility. We designed a trial eligibility form for trials of platelet transfusion to help in the assessment of relevance, which included ascertaining whether the participants had haematological malignancies, and whether the two groups could be defined in the trial on the basis of use of an alternative agent to prophylactic platelet transfusions. We recorded the reasons why potentially relevant trials did not meet the eligibility criteria.

Data extraction and management

The data extraction was updated from that performed for the previous version of this review (Estcourt 2012b). This included data extraction for all trials that were included since the previous review and also for all review outcomes that were not part of the previous review (e.g. platelet transfusion interval, quality of life).

Two review authors (MD, LE) independently conducted data extraction according to the guidelines proposed in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). We resolved disagreements between the review authors by consensus without the need for a third review author. The review authors were not blinded to names of authors, institutions, journals or outcomes of the trials. The data extraction forms were piloted in the previous version of this review (Estcourt 2012b). Due to minor changes in the format, the forms were piloted on a further trial, thereafter the two review authors (MD, LE) extracted data independently for all the trials as follows.

General information

Review author's name, date of data extraction, trial identity number, first author of trial, author's contact address (if available), citation of paper and objectives of the trial.

Trial details

Trial design, location, setting, sample size, power calculation, treatment allocation, randomisation, blinding, inclusion and exclusion criteria, reasons for exclusion, comparability of groups, length of follow‐up, stratification, stopping rules described, statistical analysis, results, conclusion and funding.

Characteristics of participants

Age, gender, ethnicity, total number recruited, total number randomised, total number analysed, types of haematological disease, lost to follow‐up numbers, drop outs (percentage in each arm) with reasons, protocol violations, previous treatments, current treatment, prognostic factors.

Interventions

Experimental and control interventions, type of platelet given, timing of intervention, dosage of platelet given, compliance to interventions, additional interventions given especially in relation to red cell transfusions, any differences between interventions.

Assessment of bias

Sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding (participants, personnel and outcome assessors), incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, other sources of bias.

Outcomes measured

Number and severity of bleeding episodes, mortality (all causes). mortality due to infection, mortality due to bleeding, overall survival, proportion of participants requiring additional interventions to stop bleeding (surgical, medical e.g. tranexamic acid, other blood products e.g. FFP, cryoprecipitate), number of platelet transfusions and platelet components, platelet transfusion interval, duration of thrombocytopenia, number of red cell transfusions and red cell components, proportion of participants achieving complete remission, time in hospital, adverse effects of treatments (e.g. transfusion reactions, transfusion‐transmitted infections, thromboembolism, development of platelet antibodies or platelet refractoriness) and quality of life.

We used both full‐text versions and abstracts to retrieve the data. We extracted publications reporting on more than one trial using one data extraction form for each trial and trials reported in more than one publication on one form only. When these sources did not provide sufficient information, we contacted the authors, trial groups or companies for additional details.

One review author (MD) entered data entry into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2012) and a second review author (LE) checked entries for accuracy.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The 'Risk of bias' assessment was updated from that performed for the previous version of this review (Estcourt 2012b).

Two review authors (MD, LE) assessed all newly included trials for possible risk of bias (as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, (Higgins 2011b). The assessment included information about the design, conduct and analysis of the trial. Each criterion was evaluated on a three‐point scale: low risk of bias, high risk of bias, or unclear risk of bias. To assess risk of bias, we included the following questions in the 'Risk of bias' table for each included trial.

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Was allocation adequately concealed?

Was knowledge of the allocated intervention adequately prevented during the trial (including an assessment of blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors)?

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (for every outcome separately)?

Were reports of the trial free of selective outcome reporting?

Was the trial apparently free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias?

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes, we recorded the number of outcomes in the treatment and control groups and estimated the treatment effect measures across individual trials as the relative effect measures (odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI)).

If continuous outcomes had been reported in a way that permitted analysis, we intended to record the mean and standard deviations (SD). For continuous outcomes measured using the same scale, the effect measure would have been the mean difference (MD) with 95% CI, or for outcomes measured using different scales, the effect measure would have been the standardised mean difference (SMD). For time‐to‐event outcomes, we planned to extracted the hazard ratio (HR) from published data according to Parmar 1998 and Tierney 2007. When appropriate, we planned to assess the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) with CIs and the number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) with CIs.

Unit of analysis issues

We did not prespecify in the original protocol how we would deal with any unit of analysis issues. In one trial, there were unit of analysis issues as three participants were re‐randomised; we used only data from one randomisation in the quantitative analysis (Higby 1974).

The trials by Geissler (Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2) included 47 participants who had previously been treated in the trials by Archimbaud (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2), so we did not combine data from these trials in a meta‐analysis.

We did not prespecify in the original protocol how we would deal with multi‐arm trials. For two outcomes that included multi‐arm trials (duration of thrombocytopenia and proportion of participants in complete remission), we split participants from the control arm equally between the intervention arms.

Dealing with missing data

We dealt with missing data according to the recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011c). We contacted authors in order to obtain information that was missing or unclear in the published report.

In trials that included participants with haematological malignancies as well as participants with solid tumours or non‐malignant haematological disorders, we extracted data for the malignant haematology subgroup from the general trial data. When this could not be done, we contacted the trial author.

Within an outcome, when there were missing data, the preferred analysis was intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis. We recorded the number of participants lost to follow‐up for each trial.

Assessment of heterogeneity

If trials were sufficiently homogenous in their trial design, we planned to conduct meta‐analysis and assess the statistical heterogeneity (Deeks 2011). However, due to problems with the way trials were reported, we performed no meta‐analyses. We planned to assess statistical heterogeneity of treatment effects between trials using a Chi2 test with a significance level at P < 0.1. We planned to use the I2 statistic to quantify possible heterogeneity (I2 > 50% moderate heterogeneity, I2 > 80% considerable heterogeneity). When necessary, we intended to explore potential causes of heterogeneity by sensitivity and subgroup analyses. This was not possible with the final data set that was obtained.

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not assess for potential publication bias (small‐trial bias) by generating a funnel plot, and statistically test using a linear regression test because the search identified an insufficient number of adequately reported trials reporting the primary outcome. We will perform such testing in future updates of this review if the search identifies at least 10 trials reporting the primary outcome. If this is the case, we will consider a P < 0.1 significant for this test (Sterne 2011).

Data synthesis

We performed analyses according to the recommendations of Cochrane (Deeks 2011). For statistical analysis, we entered data into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2012).

We used the random‐effects model for pooling the data, using the Mantel‐Haenszel method for dichotomous outcomes, and the inverse variance method for continuous outcomes.

We used the random‐effects model for sensitivity analyses as part of the exploration of heterogeneity. When heterogeneity was above 80%, we did not perform a meta‐analysis and commented on the results as a narrative.

We used GRADEprofiler to create 'Summary of findings' tables as suggested in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2011). We reported 'Summary of findings' tables that included the following outcomes.

Number of participants with at least one bleeding episode.

Total number of days on which bleeding occurred per participant.

Number of participants with at least one episode of severe or life‐threatening bleeding.

Time from randomisation to first bleeding episode.

All‐cause mortality.

Number of platelet transfusions per participant within 30 days from the start of the trial.

Adverse effects: thromboembolic events.

Quality of life.

For future updates, we will produce separate 'Summary of findings' tables for each type of alternative agent if the search identifies trials of these agents.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

The studies did not report data in sufficient detail to perform subgroup analysis or to investigate heterogeneity. For future reviews, we intend to use the following methodology.

Two subgroup analyses: we will use fever and participants' diagnostic and treatment subgroups. We will consider performing subgroup analyses on the following characteristics:

presence of fever (greater than 38 °C);

underlying disease;

type of treatment (autologous HSCT, allogeneic HSCT, or chemotherapy alone);

age of the participant (paediatric, adults, older adults (over 60 years)).

We did not perform meta‐regression as no subgroup contained more than 10 trials (Deeks 2011). For future updates of this review, if the search identifies sufficient trials for subgroup analysis, we will compare differences between subgroups using a random‐effects model when the two subgroups are independent following the guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011). If this is not possible, then we will comment on the differences as a narrative.

We did not perform as investigation of heterogeneity between trials but for future updates this will include:

age of the trial (as the type of platelet component has changed since the mid‐1970s);

different platelet component doses;

different prophylactic platelet transfusion thresholds.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not perform a sensitivity analysis due to an inadequate number of adequately reported trials. For future updates of this review, we will assess robustness of the overall results with sensitivity analysis with respect to those trials deemed to be at high risk of bias.

For dichotomous data, we will assess the influence of participant drop‐out, analysing separately RCTs with less than 20% drop‐out, RCTs with 20% to 50% drop‐out and RCTs with greater than 50% drop‐out. We will use the random‐effects model for sensitivity analyses as part of the exploration of heterogeneity.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; and Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

The database searches identified 7312 references and searching the references of included trials identified one additional reference. After removing duplicates, there were 3583. Two review authors (MD, LE) screened these references according to the Review criteria, and we excluded 3425 references as they were not an RCT or were clearly outside the scope of this review (see PRISMA diagram Figure 1). We obtained the full text of the remaining 157 references and excluded 144 (21 review articles, 35 not RCTs, 46 wrong participant group, 19 incorrect interventions and 23 secondary citations). We assessed 16 trials reported in 14 papers and deemed them eligible for inclusion (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2; Han 2015; Higby 1974; Miao 2012; Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2; Schiffer 2000; EudraCT 2015‐000929‐37; NCT01397149; NCT01656252; NCT01890746; Popat 2015; Vadhan‐Raj 2010). Six trials were ongoing and are expected to be reported (EudraCT 2015‐000929‐37; NCT01397149; NCT01656252; NCT01890746; Popat 2015; Vadhan‐Raj 2010). We included the remaining eight papers (reporting 10 trials) in the qualitative analysis (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2; Han 2015; Higby 1974; Miao 2012; Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2; Schiffer 2000).

1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

We contacted the original authors and sponsors of the trials when possible but were unable to obtain any additional information.

Included studies

The analysis included 10 completed trials reported in seven papers (see Characteristics of included studies for full details of each trial).

Design

Ten trials were published as full‐text articles (published in eight papers) between 1974 and 2015 (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2; Han 2015; Higby 1974; Miao 2012; Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2; Schiffer 2000). Eight were published in English and two in Chinese (Miao 2012). Six trials were parallel‐group two‐arm trials (Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2; Han 2015; Higby 1974; Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2), three were three‐arm trials (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Schiffer 2000), and one was a four‐arm trial (Miao 2012).

Sample sizes

The trials included 554 participants with numbers ranging from 18 (Higby 1974) to 120 (Han 2015; Miao 2012).

Setting

Six trials were conducted in a single country, with four in the USA (Higby 1974; Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2; Schiffer 2000), and two in China (Han 2015; Miao 2012). The trials by Geissler were conducted in Europe and Australia (Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2), and the trials by Archimbaud did not specify which countries the trials were conducted in (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2).

Participants

Six trials assessed participants undergoing chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukaemia (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2; Higby 1974; Schiffer 2000), two trials assessed participants undergoing intensive chemotherapy for lymphoma (Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2), and two trials assessed participants undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation (Han 2015; Miao 2012).

Interventions

Nine trials compared a TPO mimetic to placebo or standard care (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2; Han 2015; Miao 2012; Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2; Schiffer 2000).

One trial compared PPP to platelet transfusion (Higby 1974).

No trials compared artificial platelet substitutes, rFVIIa, fibrinogen concentrate or DDAVP.

Outcomes

No trial reported all the outcomes of interest. Four trials reported data for our primary outcome of number and severity of bleeding episodes within 30 days from the start of the trial (Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2; Han 2015; Higby 1974). No trial reported total number of days on which bleeding occurred, time from randomisation to first bleeding episode, red cell transfusions, total time in hospital, transfusion reactions, transfusion‐transmitted infections, platelet refractoriness or quality of life.

Funding

The manufacturer of the agent under investigation sponsored eight trials (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2; Han 2015; Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2; Schiffer 2000), and two trials did not report their source of funding (Higby 1974; Miao 2012).

Excluded studies

We excluded 144 trials from the review (see Characteristics of excluded studies for further details).

Twenty‐one trials were review articles (ASH 2003; Basciano 2012; Basser 2002; Blajchman 2001; Blajchman 2003; Catalá‐López 2015; Corrales‐Alvarez 2011; Drug news 2005; Drug news 2006; Franchini 2007; Hampton 2007; Johansson 2008; Levy 2008; Mizer 1998; Norris 2011; Peeters 2008; Prica 2014; Squizzato 2007; Vadhan‐Raj 2000; Wang 2009; Wardrop 2013).

Thirty‐five trials were not RCTs (Bauman 2011; Berstein 2002; Castaman 1997; Dickinson 2014; Elinoff 2014; Frey 2012; Gerrits 2015; Knoefler 2013; Kristensen 1993; Liesveld 2013; Mittelman 2012; Nash 2000; NCT00358540; NCT00472290; NCT00922883; NCT01194167; NCT01328587; NCT01500538; NCT01516619; NCT01550185; NCT01757145; NCT01791101; NCT01957176; NCT01980030; NCT02046291; NCT02323178; Olnes 2012; Palmblad 2008; Svensson 2014; Townsley 2015; Will 2009a; Will 2009b; Wolff 2001; Wu 2014; Xu 2008).

Forty‐six trials were on the wrong participant group (Bai 2004a; Bai 2004b; Basser 1996; Basser 1997; Bowen 2010; Bussel 2006; Bussel 2007; EudraCT number 2010‐022890‐33; Eudra CT number 2014‐000174‐19; Giagounidis 2014; Greenberg 2013; Höchsmann 2014; Jain 2013; Kantarjian 2010a; Kantarjian 2010b; Kellum 2010; Korte 2009; Malyszko 1990; Mannucci 1986; Natale 2009; NCT00102726; NCT00413283; NCT00614523; NCT00688272; NCT00903422; NCT01072162; NCT01147809; NCT01893372; NCT02052882; NCT02093325; NCT02094417; NCT02446145; Oliva 2013; Platzbecker 2015; Risitano 2014; Schuster 2002; Sekeres 2011; Seza 1997; Somlo 1999; Wang 2012; Wang 2013; Williams 2009; Winer 2015; Wire 2012; Wroblewski 2010). Seven of these trials were included in a separate review that included participants with bone marrow failure receiving no treatment or low‐dose chemotherapy (Fricke 1991; Giagounidis 2014; Greenberg 2013; Kantarjian 2010a; Mannucci 1986; Platzbecker 2015; Wang 2012).

Nineteen trials were incorrect interventions (Avvisati 1989; Basser 2000; Brenner 2004; Dunser 2004; Gallardo 1983; Glaspy 1991; Heddle 1995; Kruskemper 1966; Li 2012; Louis 1967; Matsumoto 2007; Nair 2006; Pihusch 2005; Rasche 1982; Rasche 1986; Shpilberg 1993; Takami 2002; Thompson 2000; Vannucchi 1996).

Twenty‐three trials were secondary citations for excluded trials.

Ongoing studies

We identified six ongoing trials (see Characteristics of ongoing studies table) (EudraCT 2015‐000929‐37; NCT01397149; NCT01656252; NCT01890746; Popat 2015; Vadhan‐Raj 2010). We will monitor the progress of these trials and on publication (assuming eligibility), we will include them in future updates of this review. Two of these trials have been completed or closed but the results are not published (NCT01397149; Vadhan‐Raj 2010). Three trials are due to be completed between August 2016 and February 2017 (NCT01656252; NCT01890746; Popat 2015). One trial commenced in December 2015 and is due to run for five years but the formal finish date has not been reported (EudraCT 2015‐000929‐37). Five of the ongoing trials are comparing eltrombopag to placebo in the following settings: post‐stem cell transplant (Popat 2015), newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukaemia (EudraCT 2015‐000929‐37; NCT01890746), acute myeloid leukaemia in complete remission before consolidation therapy (NCT01656252), and in participants with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (NCT01397149). One trial is comparing romiplostim (AMG531) to placebo for participants undergoing intensive chemotherapy for non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma (Vadhan‐Raj 2010). One of these trials is already completed and the final publication is awaited (Vadhan‐Raj 2000). We contacted Prof Vadhan‐Raj, the lead investigator for this trial, on 13 July 2015 and 7 August 2015, who replied on 23 August 2015 reporting that this trial will be published as a full‐text article. The preliminary results of this trial were published in 2010 in abstract format and the lack of a full‐text publication of this trial is a potential source of publication bias. This trial has a factorial design and there is insufficient information provided in the published conference abstract for it to be incorporated into this review. Overall, the six ongoing trials are expected to contribute another 424 potential participants to the systematic review.

Risk of bias in included studies

See the 'Risk of bias' table within the Characteristics of included studies table for details of our assessment for each trial and Figure 2 for a tabular summary.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Sequence generation

No trial reported details of the randomisation sequence and consequently all 10 trials were at unclear risk of bias.

Concealment of treatment allocation

Three trials reported details of concealment of treatment allocation (Higby 1974; Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2). All three trials were at low risk of bias with two trials reporting that all participants, trial staff and staff from the trial sponsors were blinded to the outcomes in the trial (Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2), and one trial reporting that participants were randomised in the hospital blood bank without the knowledge of the participants' physicians (Higby 1974). The remaining seven trials did not give sufficient detail for risk of bias to be assessed and were at unclear risk of bias (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2; Han 2015; Miao 2012; Schiffer 2000).

Blinding

Performance bias

Participants

All trials provided adequate information to assess risk of bias from blinding of participants and eight of these trials were double‐blind placebo‐controlled trials and were at low risk of bias (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2; Higby 1974; Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2; Schiffer 2000). Two trials did not blind participants and were at high risk of bias (Han 2015; Miao 2012).

Trial personnel

Nine trials provided adequate information to assess risk of bias from blinding of trial personnel and seven of these trials were double‐blind placebo‐controlled trials and were at low risk of bias (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2; Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2; Schiffer 2000). Two trials did not blind trial personnel and were at high risk of bias (Han 2015; Miao 2012). There was insufficient information provided to assess the risk of bias for one trial (Higby 1974).

Blinding of trial analysts

Nine trials provided adequate information to assess risk of bias from blinding of trial analysts and seven of these trials were double‐blind placebo‐controlled trials and were at low risk of bias (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2; Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2; Schiffer 2000). Two trials did not blind trial analysts and were at high risk of bias (Han 2015; Miao 2012). There was insufficient information provided to assess the risk of bias for one trial (Higby 1974).

Incomplete outcome data

Nine trials were at low risk of bias from incomplete outcome data (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2; Han 2015; Higby 1974; Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2; Schiffer 2000). In the two trials by Archimbaud, three participants were withdrawn from the trial before they received the intervention and all other participants were accounted for (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2). It was unclear from the reporting of these trials which of the two trials the participants were due to enter before they were withdrawn. Three participants were also withdrawn from the trials by Geissler as one was not in remission at trial entry and two withdrew early (Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2). One of the participants that was withdrawn had been randomised to PEG‐rHuMGDF 30 μg/kg (Geissler 2003‐T1), but it was unclear which trial the two other participants were in. Three participants were also excluded from the trials by Moskowitz, although it was unclear which arms or trials they had been allocated to (Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2). Two trials accounted for all the participants (Higby 1974; Schiffer 2000). One trial was at high risk from incomplete outcome data. Of 120 participants enrolled, only 89 were studied and reasons for exclusion of the remaining 31 participants were not given (Miao 2012).

Selective reporting

Two trials were at high risk of selective reporting. These trials did not have a prospectively registered protocol or trial registration but prespecified outcomes in the methods section of the paper that were not included in the results (Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2). Eight trials were at unclear risk of bias because no protocol or trial registration was published (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2; Higby 1974; Miao 2012; Schiffer 2000), or because the trial registration was retrospective (Han 2015).

Other potential sources of bias

Nine trials were had other threats to validity resulting in high risk of bias (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Higby 1974; Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2; Schiffer 2000). Four of these trials were directly sponsored by AMGEN (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2; Schiffer 2000) and one by the SUNSHINE pharmaceutical limited company (Han 2015). In one trial there was a significant difference between the ages of participants in the two groups (mean ± SD 53.3 ± 18.5 years in arm one versus 43.8 ± 19.4 years in arm two; P < 0.05 (t‐test)) (Higby 1974). For two trials (Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2) participants were included who had previously been included in the trials by Archimbaud (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2) leading to potential bias with particularly good responders being selected. There was insufficient information from one trial to assess other threats to validity (Miao 2012).

Effects of interventions

The search identified no trials of artificial platelet substitutes, rFVIIa, fibrinogen concentrate or DDAVP. There were nine trials of TPO mimetics (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2; Han 2015; Miao 2012; Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2; Schiffer 2000) and one of PPP (Higby 1974).

Thrombopoietin mimetics

Nine trials with 536 participants compared TPO mimetics to placebo or standard care (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2; Han 2015; Miao 2012; Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2; Schiffer 2000). The timing of administration, dose and type of TPO mimetic varied between trials.

Type of thrombopoietin mimetic

Seven trials compared PEG‐rHuMGDF (manufactured by AMGEN) to placebo (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2; Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2; Schiffer 2000), and two trials compared rhTPO (manufactured by Sansei Shenyang Pharmaceutical Company) to placebo (Han 2015) or standard care (Miao 2012).

Dose and timing

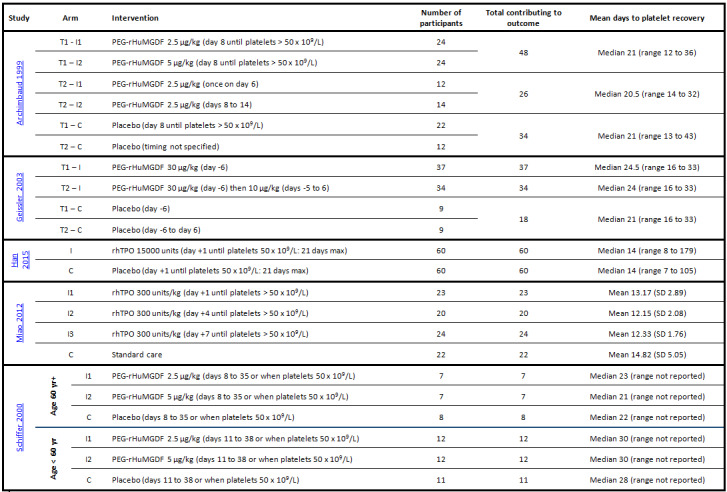

Doses ranged from 2.5 µg/kg (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Schiffer 2000) to 30 µg/kg (Geissler 2003‐T2) for PEG‐rHuMGDF. Participants treated with rhTPO received 300 units/kg in one trial (Miao 2012) and 15,000 units in one trial (Han 2015). There was heterogeneity in the duration of treatment, ranging from trials administering a single dose (Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Geissler 2003‐T1) to trials administering 28 days of treatment (Schiffer 2000). The timing of treatment also ranged between trials with a range from six days before chemotherapy started (Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2) to 11 days after chemotherapy started (Schiffer 2000). A summary of the dose and timing of the trial drug for each trial is reported in Figure 3.

3.

Trial characteristics and outcomes. No trial reported: time from randomisation to first bleeding episode; mortality due to infection; platelet transfusion interval; number of red cell transfusions per participant; proportion of participants requiring additional interventions to stop bleeding; total time in hospital; or quality of life.

C: control arm; HLA: human leukocyte antigen; I: intervention arm; max: maximum; N/A: not applicable; PEG‐rHuMGDF: pegylated recombinant human megakaryocyte growth and differentiation factor; Plt: platelet; rhTPO: recombinant human thrombopoietin; T: trial when more than one reported per paper; yr: year.

* dose was 30 μg/kg for first dose then 10 μg/kg daily thereafter; **day 1 was first day of chemotherapy; ***day 0 was day of stem cell infusion; ✔: outcome reported; ✖: outcome not reported; ①: intervention groups combined together and not reported individually; ©: control group reported together and not reported individually; ?: reported but too unclear to extract data.

Other important information when interpreting results

Forty‐seven participants randomised in the Geissler trials (Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2) had also been randomised in the Archimbaud trials (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2), and consequently could not be combined for meta‐analysis. Six trials did not report individual arms and they either combined control groups or combined intervention arms making analysis of individual doses impossible (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2; Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2). We requested additional information from AMGEN (the sponsor) but received no further information.

Bleeding

Number of participants with at least one bleeding episode

Three trials (210 participants) reported the number of participants with at least one bleeding episode (Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2; Han 2015). One trial (120 participants) reported this outcome in a way that could be analysed (Han 2015). Data from the two trials by Geissler could not be included in a meta‐analysis because the control groups and intervention groups from two trials were reported together (Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2). The results are summarised in Figure 4. There was no evidence of a difference in the risk of bleeding between participants treated with a TPO mimetic or placebo (OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.10 to 1.62, one trial, 120 participants, very low quality evidence) (Analysis 1.1). The two trials that could not be included in the meta‐analysis reported 22.5% of participants treated with a TPO mimetic and 50% of participants treated with placebo had at least one bleeding episode (Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2).

4.

Bleeding. C: control arm; I: intervention arm; max: maximum; n: number; PEG‐rHuMGDF: pegylated recombinant human megakaryocyte growth and differentiation factor; rhTPO: recombinant human thrombopoietin; T: trial when more than one reported per paper.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Thrombopoietin (TPO) mimetics versus placebo or standard care, Outcome 1 Number of participants with at least 1 bleeding episode.

Number of participants with at least one episode of severe or life‐threatening bleeding

Three trials (209 participants) reported the number of participants with at least one episode of severe or life‐threatening bleeding (Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2; Han 2015). The results are summarised in Figure 4. There was no evidence of a difference in the risk of a life‐threatening bleed between participants treated with TPO mimetics compared to participants treated with control after 30 days (OR 1.46, 95% CI 0.06 to 33.14, 209 participants, three trials, very low quality evidence) or after 90 days (OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.06 to 16.37, one trial, 120 participants, very low quality evidence) (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Thrombopoietin (TPO) mimetics versus placebo or standard care, Outcome 2 Number of participants with life‐threatening bleeding.

Total number of days on which bleeding occurred per participant

No trial reported the total number of days on which bleeding occurred per participant.

Time from randomisation to first bleeding episode

No trial reported time from randomisation to first bleeding episode.

Mortality

All‐cause mortality

Five trials (266 participants) reported all‐cause mortality (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Han 2015; Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2). Data could not be included in meta‐analysis in four trials, as the control groups were reported together (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2), and in addition to this in two trials, the intervention groups were reported in combination (Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2). The results are summarised in Figure 5. There was no evidence of a difference in all‐cause mortality for participants treated with TPO mimetics or control at 30 days (OR not estimable as no deaths, one trial, 120 participants, very low quality evidence) or at 90 days (OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.24 to 4.20, one trial, 120 participants, very low quality evidence (Analysis 1.4). Two additional trials reported all‐cause mortality at 30 days that could not be included in meta‐analysis with all‐cause mortality of 0% to 9.3% in the combined TPO mimetic arms and 11.8% in the combined control arms (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2). Two further trials reported all‐cause mortality at 90 days in a manner that could not be used for meta‐analysis with an all‐cause mortality of 13.6% in the combined intervention arms and 25% in the combined control arms (Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2).

5.

All‐cause mortality. C: control arm; I: intervention arm; max: maximum; n: number; PEG‐rHuMGDF: pegylated recombinant human megakaryocyte growth and differentiation factor; rhTPO: recombinant human thrombopoietin; T: trial when more than one reported per paper;

➀: = after one cycle of chemotherapy; O: up to 90 days (data extracted from survival curves).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Thrombopoietin (TPO) mimetics versus placebo or standard care, Outcome 4 All‐cause mortality.

Mortality secondary to bleeding

No trial reported mortality due to bleeding.

Mortality secondary to infection

No trial reported mortality due to infection.

Overall survival

Three trials (158 participants) reported overall survival with no trials reporting data in a way that could be analysed (Han 2015; Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2). There was no evidence of a difference in overall survival in the trial that reported this outcome, with a P value of 0.368, no HR or CI reported (one trial, 120 participants) (Han 2015). In the remaining two trials, data could not be pooled, as the control arms and intervention arms were combined (Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2). HRs in these two trials were not reported but at 8.5 years' median follow‐up, Kaplan‐Meier estimates for overall survival were reported as 59% for the combined group of participants treated with a TPO mimetic and 31% for the combined group of participants treated with placebo (Moskowitz 2007‐T1; Moskowitz 2007‐T2).

Proportion of participants requiring additional interventions to stop bleeding

No trial reported additional interventions to stop bleeding.

Platelet transfusions

Number of platelet transfusions per participant

Six trials (378 participants) reported platelet transfusions per participant (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2; Han 2015; Schiffer 2000). One trial presented data in a way that permitted meta‐analysis (Han 2015). There was a significant reduction in platelet transfusion requirements between participants treated with TPO mimetics and participants treated with control (mean difference ‐3 units, 95% CI ‐5.39 to ‐0.61, one trial, 120 participants, very low quality evidence (Analysis 1.3). Data could not be combined in the remaining five trials, as in four trials, the control arms had been combined and data were presented as medians (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2), and in one trial participants were divided into those aged under 60 years and those aged over 60 years and presented as medians preventing combined analysis. There was considerable clinical heterogeneity between these trials. Additionally, 47 participants from the trials by Geissler (Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2) had previously been included in the trials by Archimbaud (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2). The results are summarised in Figure 6. Platelet transfusions per participant were presented as medians for five of the trials assessing TPO mimetics (Archimbaud 1999‐T1; Archimbaud 1999‐T2; Geissler 2003‐T1; Geissler 2003‐T2; Schiffer 2000. The range of medians presented was 4 to 10 platelet transfusions for participants receiving TPO mimetics and 4 to 8 transfusions for participants treated with placebo.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Thrombopoietin (TPO) mimetics versus placebo or standard care, Outcome 3 Platelet transfusions.

6.

Mean number of platelet transfusions. C: control arm; I: intervention arm; max: maximum; PEG‐rHuMGDF: pegylated recombinant human megakaryocyte growth and differentiation factor; rhTPO: recombinant human thrombopoietin; SD: standard deviation; T: trial when more than one reported per paper; yr: year.

➀: after one cycle of chemotherapy; O: until 28 days after last cycle of chemotherapy; ➁: until 60 days of treatment.

Platelet transfusion interval

No trial reported platelet transfusion interval.

Duration of thrombocytopenia