Abstract

Introduction

Korean women are reluctant to pursue in-person smoking cessation treatment due to stigma attached to women smokers and prefer treatment such as telephone and online smoking cessation programs that they can access secretively at home. However, there is some evidence that face-to-face interaction is the most helpful intervention component for them to quit smoking.

Methods

This study is a pilot clinical trial that examined the acceptability and feasibility of a videoconferencing smoking cessation intervention for Korean American women and compared its preliminary efficacy with a telephone-based intervention. Women of Korean ethnicity were recruited nationwide in the United States and randomly assigned at a ratio of 1:1 to either a video arm or a telephone arm. Both arms received eight 30-minute weekly individualized counseling sessions of a deep cultural smoking cessation intervention and nicotine patches for 8 weeks. Participants were followed over 3 months from the quit day.

Results

The videoconferencing intervention was acceptable and feasible for Korean women aged <50 years, whereas it was not for older women. Self-reported abstinence was high at 67% and 48% for the video and telephone arm at 1 month post-quit, respectively. The rates declined to 33% for the video arm and 28% for the telephone arm at 3 months post-quit when salivary cotinine test was performed.

Conclusion

Findings support that both videoconferencing and telephone counseling can be effective, and personal preference is likely an important factor in treatment matching. The deep cultural smoking cessation intervention may account for the outcomes of telephone counseling being better than prior studies in the literature for Korean women.

Keywords: smoking cessation, women, videoconferencing, nicotine, remote biochemical validation, Asian American

Introduction

Korean Americans are the fifth largest Asian ethnic group in the United States, ~1.7 million.1 Korean men and women smoke at the highest rates within the Asian American population.2,3 The 2009–2011 US Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health Risk Factor Survey reported that Korean men and women in New York City smoked at 36% and 11%, respectively, whereas the rates were 19% and 4% for all Asian men and women, respectively.3 The rate for the whole city population was 14%.3 In contrast to the overall decline of smoking rates across all racial and ethnic groups in the United States, the rate among Korean women in California has steadily increased from 8% to 21% in the past decade.4 California is the only state that has disaggregated data by Asian ethnic subgroups, and hence, it is impossible to assess whether other states would show the same trend.

Several factors may contribute to the increase of smoking prevalence in Korean women. First, many Korean women in a qualitative study indicated that they learned the behavior from husbands after having been exposed to their secondhand smoke for a long time.5 Korean Americans are known for the highest rate (eg, 58%) of secondhand smoke exposure within the Asian American population.6,7 The women could have been slowly addicted to nicotine after the long exposure, which led them to the uptake. Second, Korean American women are more likely to smoke as they acculturate into the mainstream American culture.8,9 The rate of current smoking was once reported as high as 17% for the most culturally assimilated Korean American women, whereas it was as low as 3% for the least acculturated.9 Third, young women in Korea now have a high rate of smoking uptake (10%–15%), and many of them come to live in the United States for study and work.5,10,11

Three smoking cessation studies have been conducted on Korean Americans, and women comprised only a small proportion of the participants (11%–17%).12–14 The Korean-language California (CA) quit-line service (N=848) produced a higher abstinence rate than self-help materials (15% vs 5%); however, further analysis revealed that the service was effective only for men (S-H Zhu, personal communication on October 23, 2013).12 An online smoking cessation program (N=1,409) had no treatment effect over self-help materials (11% vs 13%).13 In contrast, an in-person smoking cessation intervention (N=109), which was adapted at a deep structural level of Korean culture produced a higher abstinence rate than a standard smoking cessation intervention (38% vs 11%). The deep cultural intervention was effective for both men (34.8%) and women (55.6%).14 Resnicow et al15 stated that deep cultural adaptation integrates core cultural values of the target group and addresses psychosocial, social, and environmental forces affecting the behavior. They differentiated it from surface-level cultural adaptation which is the mere translation of languages, words, and pictures that are frequently observed in smoking cessation studies on racial and ethnic minorities.16

Korean American women are less likely to seek smoking cessation treatment due to the strong cultural taboo against women who smoke.5 They desire a treatment option such as telephone counseling that can be accessed secretively from home.14,15 However, the quit-line service in Korea produced a low abstinence rate (eg, 4.5%) showing no treatment effect over quitting alone.17 Several women in an in-person smoking cessation study mentioned during the exit survey that face-to-face interaction with the therapist was one of the most helpful intervention components.14 According to them, recalling the image of the therapist who had shown genuine interest in their health helped them resist smoking temptations and maintain abstinence. Based on these qualitative findings, videoconferencing smoking cessation intervention might be an ideal alternative to an in-person one for Korean American women because they can access the treatment secretively at home while having the face-to-face interaction.

Only one study compared the relative effectiveness of a videoconferencing smoking cessation intervention with an in-person smoking cessation intervention.18 The study (N=554) was conducted in Canada for smokers in rural areas and found no difference in abstinence rates between the in-person and videoconferencing (tele-health) interventions (28% vs 26%). Another study (N=566) in the United States compared videoconferencing and telephone-based smoking cessation interventions for smokers in primary care clinics, and abstinence rates were similar between the two approaches (10% vs 12%).19 The purposes of the present study were to examine the acceptability and feasibility of a videoconferencing smoking cessation intervention for Korean American women and to compare abstinence rates between the videoconferencing and telephone-based smoking cessation interventions.

Methods

This is a pilot two-arm randomized controlled trial of a videoconferencing smoking cessation intervention compared with a telephone-based intervention for Korean American women. Participants were randomized at a ratio of 1:1 to either the video arm or the telephone arm, and both arms received the same intervention that was adapted at a deep level of Korean culture.14,20 The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Massachusetts Boston, and the participants signed informed consent prior to baseline assessment.

Participants

Participants were community-residing Korean American women who 1) self-identified Korean ethnicity, 2) aged between 18 and 65 years, 3) had smoked at least ten cigarettes per day for the past 6 or more months, 4) were willing to quit smoking within the next 4 weeks from the baseline assessment, 5) had no contraindication to nicotine patches such as active skin disease, 6) were not pregnant or lactating and agreed to use an approved form of birth control (eg, oral medications, condoms, and intrauterine devices) during the study, and 7) had access to a mobile phone or computer for video calls. Individuals were excluded if they self-reported as currently receiving treatment for mental illness, including alcohol dependence. Women >65 years were also excluded from the study based on the assumption that they might have difficulty accessing or operating a video call application.

Procedure

Study ads calling for Korean women who wanted to quit smoking were posted in two nationwide online communities of Korean American women (www.missyusa.com and www.missycoupons.com) and ten regional online communities of Korean Americans in Atlanta, GA; Boston, MA; Centreville, VA; Los Angeles, CA; New York City, NY; San Francisco, CA; Seattle, WA, etc. The study was also advertised in two offline newspapers, one in Los Angeles and the other one in New York City where a large number of Korean immigrants have settled. The ads were posted from November 2014 to August 2015, and participants were recruited for a year from November 2014 to October 2015.

Korean American women were screened for eligibility through telephone interviews, and those who met the selection criteria were informed about the purpose and procedure of the study. They were also informed that they had an equal chance of being assigned to either the video or the telephone arm. They were further informed that the intervention in both arms was the same except for its delivery mode. Those who agreed to participate in the study were asked about contact information such as name, mailing address, email address, and working telephone number. They then received a package of informed consent form and baseline questionnaires. Once the women returned a completed set of the package to the research team, they were assigned to one of the two arms by a computer-generated random number. The numbers were stored in sealed envelopes, and the numbers that had a black dot next were assigned to the video arm. The sequence of the assignment was blinded to research staff and participants.

Interventions

Participants in both arms received eight weekly individualized counseling sessions of a deep culturally adapted smoking cessation intervention, and each session was scheduled for 30 minutes. They also received transdermal nicotine patches for 8 weeks: 21 mg for 4 weeks and 14 mg and 7 mg for each, 2 weeks. Prior to the first session, all women in the video arm installed a video call application with an assistance from research staff. Two therapists provided counseling by calling participants in both arms for scheduled sessions. The therapists were not assigned to an arm because there was a large difference in years of counseling between the two. The smoking cessation intervention of both arms was adapted at a deep structural level of Korean culture by incorporating core cultural values and addressing social, environmental, and historical forces affecting the smoking behavior of Korean American women.15 For example, to explain the harmful effects of carbon monoxide (CO), therapists used an analogy of coal briquette CO gas poisoning that has been claiming many lives in Korea.21,22 The coal briquette is one of the traditional heating systems in Korea. A burning briquette is placed under a thick masonry floor of a house, which produces large amounts of CO.

Individualized counseling

The target quit day was set between the third and fourth sessions depending on one’s readiness for quitting. The pre-quit counseling sessions were focused on education about immediate benefits of quitting, neurobiological changes in the brain associated with nicotine addiction, and behavioral strategies in preparation for the quit day. In contrast, post-quit sessions varied by individual needs depending on abstinence status, severity of nicotine withdrawal symptoms, and adherence to nicotine patches. In addition, Korean-specific cessation information was provided throughout the 8-week intervention period, and its detailed description has been published elsewhere.14,20,21

Family coaching

Family coaching was provided to both arms two times before and after the quit day. Before the quit day, the coaching was focused on educating family members about dreadful health consequences of smoking, harms associated with exposure to secondhand smoke, and the importance of family support in one’s successful smoking cessation. They were advised to relate firm antismoking messages to the participant. The coaching after the quit day was focused on supporting the smoker’s cessation efforts by praising, avoiding conflicts, and monitoring adherence to nicotine patches. If there was a family member (eg, husband, son, or daughter) who smoked but refused to quit at the time, the person was advised not to smoke around the participant. If the family member firmly agreed to use nicotine patches for quitting, he or she was provided with one-time brief counseling and a free supply of nicotine patches for 8 weeks.

Nicotine patches

Participants in both arms received 8 weeks of nicotine patches at two separate occasions: 4-weeks of 21 mg and each 2 weeks of 14 mg and 7 mg. Participants were educated about the pharmacological mechanism, correct usage of nicotine patches, and proper management of side effects. Adherence to the medication was monitored by asking participants to show used patches since the last time during video calls for the video arm or by simply asking how many patches they had used since the last time for the telephone arm.

Self-help materials

Participants in both arms received self-help materials that have information on the following areas: contents of a cigarette, smoking-related health problems, harms associated with exposure to secondhand smoke, immediate health benefits of quitting, strategies to deal with craving and other nicotine withdrawal symptoms, and proper use of nicotine patches and all other cessation medications approved by the Food and Drug Administration. The materials were written in the language that the participant preferred.

Data collection and measures

The primary outcomes of the study were the acceptability and feasibility of the videoconferencing smoking cessation intervention. Its secondary outcomes were the rates of 7-day point prevalence at each follow-up and 3-month prolonged abstinence. The 7-day point prevalence abstinence was defined as having not smoked a single puff for the past 7 days, and the 3-month prolonged abstinence was sustained abstinence after an initial 2-week grace period.23 Those who reported abstinence at post-quit 3-month follow-up were asked to perform a salivary cotinine test using a NicAlert® test strip (Nymox Pharmaceutical Corporation, Hasbrouck Heights, NJ, USA). They conducted the test following step-by-step instructions provided by a female research staff who closely monitored the whole process through a video call. The staff member read the result during the same video call when the blue band of the test strip disappeared, which took ~25–30 minutes. After the video call, she received a picture of the test strip from the participant and then forwarded it to another research staff for an independent reading. Those who reported the use of any nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) products for the past 7 days were excluded from the test.

Baseline assessment was done prior to randomization, and the participants were followed up weekly during the 8-week cessation intervention and then monthly till post-quit 3 months. All measures but Autonomy over Tobacco Scale (ATS) had been translated into Korean and tested for use with Korean Americans in previous studies.14, The measures were administered in a paper-and-pencil format and took ~35 minutes to complete.

Demographic data

These data include age, marital status, education, annual family income, health insurance coverage, and employment status.

A brief-form Suinn-Lew Asian self-identity acculturation scale

This measure consists of five items (language spoken, language preferred, language read, childhood friends, and cultural identity) that have the highest item-to-total correlations among the 21 items in its full version.24 Each item can be scored from 1 “very Korean-culture oriented” to 5 “very American-culture oriented”, and the scale score is the mean of the scores of the five items. A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.74 was obtained in the present study.

Smoking history

This measure gathers information on the following areas: age of smoking onset, an average number of cigarettes smoked per day, history of indoor house or office smoking for the past 7 days, any past-year quit attempts at which abstinence lasted at least 24 hours, and presence of other smokers in the household.

Fagerström test for nicotine dependence

This measure assesses the intensity of physiological dependence on nicotine and consists of six items.25 Each item has a weighted score of an answer ranging from 0 to 3. Although the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence is most widely used for nicotine dependence, it yielded poor validity and reliability for Korean American women.26 A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.32 was obtained in the present study.

Autonomy over tobacco scale

This measures assesses diminished autonomy over tobacco use and consists of 12 question items on a 4-point scale ranging from “not at all” to “very well.”27 Because of the poor psychometric findings of the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence with Korean American women in previous studies,14,26 we also used the Autonomy over Tobacco Scale. The measure was used for the first time with Korean American women and prior to the use, it was translated and back translated with a rigor required for cross-cultural validation. A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87 was obtained in the present study.

Alcohol use disorder identification test

The measure consists of ten items and the score of each item can range from 0 to 4.28 Items 1–3 assess individuals’ alcohol consumption, items 4–6 examine abnormal drinking behavior, items 7 and 8 detect adverse psychological reactions, and items 9 and 10 assess alcohol-related problems. A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92 was obtained in the present study.

Center for epidemiologic studies depression scale

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale29 consists of 20 items and is an adequate screening instrument for depressive disorder in the general population. Participants rate how often they have experienced each symptom over the past week on a 4-point (0–3) scale from “rarely” (ie, once per day) to “most of the time” (ie, 5–7 days). The scale has been tested with Koreans and instead of 16, a cutoff point of 21 was recommended as the best predictor of depression in the group.30 A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.95 was obtained in the present study.

Perceived risks and benefits questionnaire

This is an indirect measure of attitudes toward quitting and consists of two subscales: 18 items on perceived risks of quitting (eg, “I will be less able to concentrate” and “I will miss the taste of cigarettes”) and 22 items on perceived benefits of quitting (eg, “I will smell cleaner” and “I will feel proud that I was able to quit”).31 Participants are asked to assess the likelihood of each item on a 7-point scale (1 “no chance at all” and 7 “certain to happen”) if they are to stop smoking. The scale was adapted with 14 items for each subscale based on findings from previous studies with Korean Americans.14,32 Cronbach’s alphas were 0.87 and 0.84 for perceived risk and perceived benefit subscales, respectively.

Perceived social norm index

This measure assesses normative beliefs (ie, “I believe that my family [my friends] wants me to quit smoking”) and motivation to comply (ie, “I am willing to comply with the belief”).33 Score for each item can range from −3 “strongly disagree” to +3 “strongly agree”, and the scale score is the sum of the scores of the two items. Smokers are often conflicted by the discrepancy between perceived family and perceived peer social norms, for quitting. Hence, the scores of the two-referent (family and peers) groups were not combined for internal reliability.

Self-efficacy in quitting scale

This is a self-report measure asking a person’s confidence in avoiding smoking when the person faces ten high smoking-risk situations.34 Each of the items is measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 “completely unsure” to 5 “completely sure”. The scale score is the sum of the scores of the ten items. A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87 was obtained in the present study.

Client satisfaction questionnaire

It is an eight-item brief assessment, asking individuals about the quality of the service that they received, the extent that the intervention met their needs, willingness to recommend the intervention to others in need of similar help, and willingness to have the intervention in future if additional services are offered.35 Each item is coded with a 4-point Likert-type scale and the scale score is the sum of the scores of the eight items. The scale has been frequently used for evaluations of diverse interventions. A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85 was obtained in the present study.

Self-reported cessation outcome

Participants self-reported whether they had been abstinent or smoking at each follow-up. If not smoking, how long they had been abstinent and whether there were any lapses. If smoking, how long they had been smoking regularly and how many cigarettes they were smoking per day.

NicAlert test

It is a semiquantitative measure of cotinine based on a colorimetric immunoassay reaction. Its test strip displays seven zones that represent a range of cotinine levels from 0 (cotinine concentration =0–10 ng/mL) to 6 (cotinine concentration ≥2,000 ng/mL). Cotinine is the major proximate metabolite of nicotine and has a long half-life of ~15–19 hours.36 Thus, it is widely used as a biological marker of nicotine exposure. Those who yielded results other than 0 (cotinine concentration 0–10 ng/mL) were all treated as smoking irrespective of self-report.

Data analyses

The present study was a pilot clinical trial with the target sample 50 (25 per arm), which was not adequately powered. Data analyses were performed using STATA 14 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Demographics, smoking history, and psychosocial variables were compared between the telephone and video arms, using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and Mann–Whitney U-tests for continuous variables. The U scores were then converted to z scores for better understanding of the results. Using the intent-to-treat analytic strategy, we included all participants in treatment outcome analyses and those who were missing at follow-ups were all treated as smoking. Survival analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between treatment condition and abstinence using the Kaplan–Meier log-rank test and the Cox proportional hazards model when including possible covariates such as nicotine dependence and self-efficacy.

Results

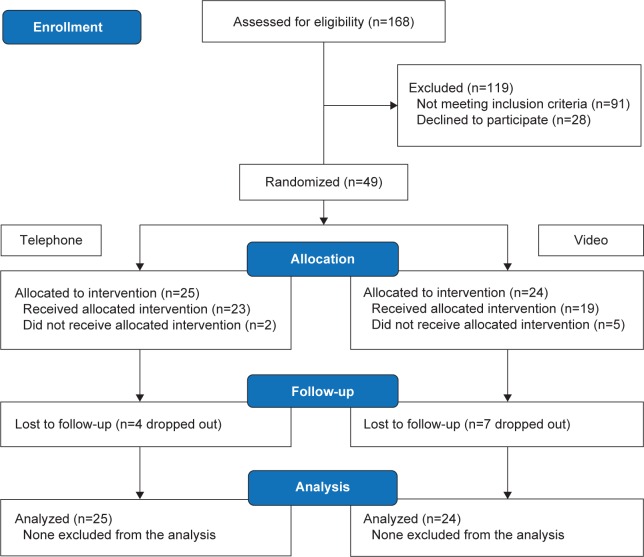

A total of 168 were assessed for eligibility, and of these, 91 (54.2%) were deemed ineligible, 28 (16.7%) refused, and 49 (29.2%) participated in the study (Figure 1). We stopped recruitment before the target sample 50 when several women declined participation and a new year arrived. The most frequent reason given for the decline was time constraint of the intervention. Nine women declined because they did not like doing videoconferencing and some suspected that their face would be videotaped during the session and shown to others. They seemed to be ashamed of being a smoker and afraid that someone might find it out. Among those ineligible, 30 were males, 28 non-daily or light smokers (<10 cigarettes per day), and 15 proxy callers who contacted on behalf of smokers. Eighteen women were further excluded because they did not have access to a video call application (neither computer nor smartphone).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram showing a flow of subjects in the study.

Abbreviation: CONSORT, CONsolidated Standards of Reporting Trials.

Of the 49 participants, 25 were assigned to the telephone arm and the remaining to the video arm. Baseline characteristics of the participants are compared between the two arms in Table 1. Those in the telephone arm perceived more risks of quitting than their counterparts in the video arm (z=1.99, P<0.05). Participants in the telephone arm tended to be less educated (χ2[2] =5.72, P=0.06) and have lower self-efficacy in quitting (z=−1.72, P=0.09) than those in the video arm. All other baseline characteristics showed no difference. Combining the two arms, approximately 80% of the participants (n=39) had been in the United States for ≥10 years at the time of the study. Most (81.6%, n=40) smoked light or ultralight cigarettes, and Marlboro (30.6%, n=15) and Parliament (22.4%, n=11) were most favored brands. Only three (0.06%) smoked mentholated cigarettes.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the groups

| Characteristic | Telephone (n=25) mean ± SD, N (%) |

Video (n=24) mean ± SD, N (%) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (range =20–63 years) | 44.9±11.7 | 45.3±12.8 | 0.80 |

| Marital status | 0.78 | ||

| Married or living with partner | 12 (48.0) | 13 (54.2) | |

| Single or divorced | 13 (52.0) | 11 (45.8) | |

| Education | 0.06 | ||

| Elementary to high school | 13 (52.0) | 11 (45.8) | |

| Some years in college | 6 (24.0) | 1 (4.2) | |

| Baccalaureate or higher degree | 6 (24.0) | 12 (50.0) | |

| Annual family income | 0.58 | ||

| <$40,000 | 9 (36.0) | 11 (45.8) | |

| $40,000–$79,999 | 4 (16.0) | 5 (20.8) | |

| >$80,000 | 12 (42.0) | 8 (33.3) | |

| Medical insurance | 0.36 | ||

| Yes | 15 (60.0) | 18 (75.0) | |

| No | 10 (40.0) | 6 (25.0) | |

| Employed | 0.10 | ||

| Yes | 16 (64.0) | 21 (87.5) | |

| No | 9 (36.0) | 3 (12.5) | |

| Acculturation (range =1.0–3.4) | 1.9±0.5 | 1.8±0.5 | 0.57 |

| Age at smoking onset (range =13–43) | 22.6±5.6 | 23.5±7.1 | 0.99 |

| Cigarettes per day (range =10–31) | 17.2±6.4 | 15.2±4.4 | 0.28 |

| Indoor house smoking | 0.25 | ||

| Yes | 13 (52.0) | 8 (33.3) | |

| No | 12 (48.0) | 16 (66.4) | |

| Indoor office smoking | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 2 (8.0) | 1 (4.2) | |

| No | 23 (92.0) | 23 (95.8) | |

| 24 hours abstinence in the past year | 0.38 | ||

| Yes | 14 (64.0) | 17 (66.7) | |

| No | 11 (36.0) | 7 (33.3) | |

| Presence of other smokers in the family | 0.55 | ||

| Yes | 10 (40.0) | 7 (29.2) | |

| No | 15 (60.0) | 17 (70.8) | |

| FTND score (range =2–9) | 6.0±1.7 | 5.6±1.6 | 0.51 |

| Autonomy over tobacco (range =21–48) | 35.4±7.3 | 33.3±7.9 | 0.39 |

| Alcohol use problems (range =0–28) | 5.0±7.5 | 4.8±7.3 | 0.92 |

| Depressive symptoms (range =0–49) | 13.8±11.4 | 13.6±16.3 | 0.55 |

| Perceived risks of quitting (range =1.9–6.6) | 5.3±0.9 | 4.8±1.0 | 0.05 |

| Perceived benefits of quitting (range =3.6–6.9) | 5.8±0.8 | 6.0±0.8 | 0.35 |

| Perceived family norm for quitting (range =1–6) | 4.4±1.4 | 4.0±2.0 | 0.46 |

| Perceived peer norm for quitting (range =−2–6) | 2.6±2.4 | 2.5±2.6 | 0.98 |

| Self-efficacy in quitting (range =10–44) | 26.0±7.8 | 29.5±8.6 | 0.09 |

Abbreviations: FTND, Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence; SD, standard deviation.

Although included in the analyses, seven participants (14.3%, 7/49) dropped out of the study before beginning the allotted intervention. Four in the video arm withdrew after randomization when their request for the telephone arm was not granted. One in the video arm and two in the telephone arm also dropped out due to conflict with schedule.

At the end of the intervention, including those who dropped out before the intervention, the two arms did not differ in the number of sessions attended (telephone =6.72±2.19 vs video =5.75±3.14, z=0.88, P=0.38), the number of nicotine patches used (telephone =37.08±23.68 vs video =28.21±21.99, z=1.09, P=0.28), and the completion of the eight sessions (telephone =48% vs video =38%, P=0.57). Combining the two arms, 77.6% (38/49) remained in the study until the last follow-up assessment.

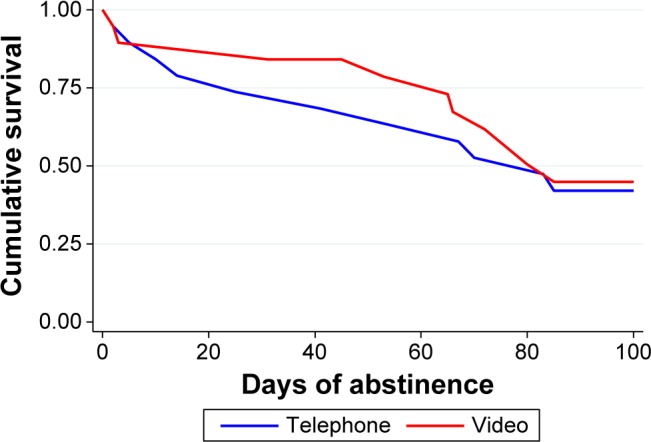

The rates of 7-day point prevalence abstinence are shown over time by intervention condition in Table 2. Among the 20 who reported abstinence at 3-month follow-up, 16 (80%) conducted home-based salivary cotinine tests, and all but one yielded level 0 (cotinine concentration =0–10 ng/mL). The two readers of the results showed no discrepancy in their readings. Three (two in the telephone arm and one in the video arm) refused the test and one in the telephone arm was excluded because she reported the use of over-the-counter nicotine patches. Self-reported, cotinine-confirmed 3-month prolonged abstinence rate was 28.0% for the telephone arm and 29.2% for the video arm. Of note, one in the video arm whose cotinine test result was level 0 was treated as smoking in the estimate because she later reported that she had smoked two cigarettes about a week ago when the cotinine test was initially scheduled. When the analysis was done per study protocol, including only those who received at least the first session of the intervention, the rate of 3-month prolonged abstinence was changed to 30.4% for the telephone arm and 36.8% for the video arm. Kaplan–Meier survival curve showed no difference in days of abstinence between the two arms (Figure 2). Likewise, Cox proportional hazards model yielded no significant finding (hazard ratio =0.86, 95% confidence interval 0.36–2.02).

Table 2.

Seven-day point-prevalence abstinence by intervention condition

| Intervention condition | Post-quit 1 month (self-report) |

Post-quit 2 months (self-report) |

Post-quit 3 months (self-report) |

Post-quit 3 months (salivary cotinine test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telephone arm | 48.0% | 52.0% | 40.0% | 28.0% |

| Video arm | 66.7% | 58.3% | 41.7% | 33.3% |

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve of days of abstinence between the two arms.

Note: Log-rank test χ2 =0.13, P=0.72.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study testing the feasibility and acceptability of a videoconferencing smoking cessation intervention for Asian women. We found that the videoconferencing delivery mode seems to be feasible and acceptable only for younger Korean women under 50 years. Many Korean women aged ≥50 years were suspicious of doing the interview through video calls (face talk) and some erroneously believed that their face would be videotaped for others to see. Furthermore, most women aged ≥60 years did not have access to a video call equipment (computer or smartphone) or had difficulty installing a video call application.

The study raised several serious concerns with regard to the acceptability and feasibility of videoconferencing cessation interventions for Korean women in 50–65 years. First, the refusal rate of the women was much higher than younger women (18–49 years). Despite repeated explanations, some women, especially those who were >50 years of age, were suspicious of the motive of video calls. It seemed that they mistook video calling for videotaping. They were afraid that their smoking status could be known to others in their small Korean community had they participated in videoconferencing. Second, many Korean women in their 60s declined participation because they did not know how to do a video call. This finding is supportive of the study result that older adults (50–65 years) showed a lower performance than younger adults (20–35 years) when handling the interface of a mobile phone.37

Videoconferencing smoking cessation intervention failed to add any treatment effect to telephone-based intervention for Korean American women. One possible explanation for the null finding might be the fact that the two interventions were the same with deep cultural adaptation. Of note, the continine-confirmed 7-day point prevalence abstinence rates (28.0% and 33.3%) achieved by the present study were lower than that (55.6%) achieved by Korean American women who received in-person cessation counseling of the same culturally adapted intervention.14 However, the rates were nonetheless higher than that (0%) of Korean American women who received an in-person standard cessation intervention14 and the self-reported abstinence rate (12.8%) of Korean American women who used the CA quitline service (S-H Zhu, personal communication on October 23, 2013). Here, the latter two interventions were adapted at a surface-level of Korean culture (ie, the mere translation of the Korean language and Korean therapists). There is a need for studies testing the relative effectiveness of the deep cultural telephone-based cessation intervention against surface-level cultural ones for Korean American women.

Remote biochemical validation of smoking abstinence seems to be feasible with a NicAlert test strip. Although participants self-administered the test at home, we had a female research staff to monitor the whole testing process through a video call. The NicAlert test is relatively cost-effective compared to breath CO test. The test strips cost $12–$15 a piece, whereas CO meters generally cost approximately $600–$1,000 each. Although a mobile-phone-based CO meter had been pilot-tested,38 it is not yet commercially available. We also found that breath CO tests were less reliable than salivary cotinine tests in our previous study.14 Breath CO output is largely affected by speed of emptying the lung.39 For example, when heavy smokers switched from exhaling slow to exhaling fast, they had an ~30% reduction in CO outputs. Cotinine assessment also has a limitation. It cannot be done during the use of nicotine replacement therapy. Thus, in the present study, the NicAlert test was done only once at post-quit 3 months after the completion of the 8-week nicotine patches.

Limitations

The present study has several limitations and notable strengths. First, all findings are preliminary because of the pilot nature of the study. Korean American women are among the hardest-to-recruit groups for smoking cessation, and as expected, many women, especially those >50 years, were reluctant to participate in a videoconferencing smoking cessation intervention. Second, the study has limited generalizability because we excluded Korean American women who did not have access to a video call equipment such as smartphone or computer or who were >65 years of age. Nevertheless, the study is the first of its kind finding that telephone counseling intervention for Korean American women yielded an abstinence rate that was similar to that of videoconferencing one. The study also found that remote biochemical validation of smoking abstinence is feasible with a NicAlert test at a relatively low cost.

Conclusion

Both telephone-based and videoconferencing cessation interventions seem to be effective for younger Korean women <50 years. Thus, personal preference may be an important factor in treatment matching for them. On the other hand, telephone-based intervention seems to be the only appropriate treatment option for older Korean women ≥50 years. To be effective, both interventions need to be adapted at a deep structure level of the culture as like the one provided in the present study. A large scale of a telephone-based cessation study should be conducted with Korean American women, comparing the relative effectiveness of a deep cultural smoking cessation intervention with a standard cessation intervention or a surface-level cultural cessation intervention. As a final note, researchers and clinicians should include a home-based salivary cotinine test as part of a smoking cessation intervention if telephone cessation counseling is provided for smokers in remote areas.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (1R56DA036798-01A1) to Sun S Kim.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.East-West Center Asia matters for America: Korean-American population data. [Accessed March 3, 2016]. Available from: http://www.asiamattersforamerica.org/southkorea/data/koreanamericanpopulation.

- 2.Caraballo RS, Yee SL, Gfroerer J, Mirza SA. Adult tobacco use among racial and ethnic groups living in the United States, 2002–2005. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(3):A78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li S, Kwon SC, Weerasinghe I, Rey MJ, Trinh-Shevrin C. Smoking among Asian Americans: acculturation and gender in the context of tobacco control policies in New York City. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14(5):18S–28S. doi: 10.1177/1524839913485757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.University of California Los Angeles California Health Interview Survey, adult survey, 2011. [Accessed June 13, 2015]. Available from: http://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/chis/Pages/default.aspx.

- 5.Kim SS, Kim S, Seward G, Fortuna L, McKee SA. Korean American women’s experiences with smoking and factors associated with their quit intentions. ISRN Addiction. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/796570. ID 796570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma GX, Tan Y, Fang CY, Toubbeh JI, Shive SE. Knowledge, attitudes and behavior regarding secondhand smoke among Asian Americans. Prev Med. 2005;41(2):446–453. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myung SK, McDonnell DD, Kazinets G, Seo HG, Moskowitz JM. Relationships between household smoking restrictions and intention to quit smoking among Korean American male smokers in California. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25(2):245–250. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.2.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim SS, Ziedonis D, Chen KW. Tobacco use and dependence in Asian Americans: a review of the literature. Nicotine Tobacco Res. 2007;9(2):169–184. doi: 10.1080/14622200601080323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song YJ, Hofstetter CR, Hovell MF, et al. Acculturation and health risk behaviors among Californians of Korean descent. Prev Med. 2004;39(1):147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim SS, Lee Ho, Kiang P, Kalman D, Ziedonis DM. Factors associated with alcohol problems among Asian American college students: gender, ethnicity, smoking and depressed mood. J Subst Use. 2014;19(1):12–17. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim S. Smoking prevalence and the association between smoking and sociodemographic factors using the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data, 2008 to 2010. Tobacco Use Insights. 2012;5:17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu SH, Cummins SE, Wong S, Gamst AC, Tedeschi GJ, Reyes-Nocon J. The effects of a multilingual telephone quitline for Asian smokers: a randomized controlled trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(4):299–310. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDonnell DD, Kazinets G, Lee HJ, Moskowitz JM. An internet-based smoking cessation program for Korean Americans: results from a randomized controlled trial. Nicotine Tobacco Res. 2011;13(5):336–343. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim S, Kim S, Fang H, Kwon S, Shelley D, Ziedonis D. A culturally adapted smoking cessation intervention for Korean Americans: a mediating effect of perceived family norm toward quitting. J Immigrant Minority Health. 2015;17(4):1120–1129. doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-0045-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Resnicow K, Baranowski T, Ahluwalia JS, Braithwaite RL. Cultural sensitivity in public health: defined and demystified. Ethn Dis. 1999;9(1):10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu JJ, Wabnitz C, Davidson E, et al. Smoking cessation interventions for ethnic minority groups – a systematic review of adapted interventions. Prev Med. 2013;57(6):765–775. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Myung SK, Seo HG, Park EC, Lim MK, Kim Y. An observational study of the Korean proactive quitline service for smoking cessation and relapse prevention. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(4):583–590. doi: 10.1177/003335491112600415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlson LE, Lounsberry JJ, Maciejewski O, Wright K, Collacutt V, Taenzer P. Telehealth-delivered group smoking cessation for rural and urban participants: feasibility and cessation rates. Addict Behav. 2012;37(1):108–114. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richter KP, Shireman TI, Ellerbeck EF, et al. Comparative and cost effectiveness of telemedicine versus telephone counseling for smoking cessation. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(5):e113. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim SS. A culturally adapted smoking cessation intervention for Korean Americans: preliminary findings. J Transcult Nurs. 2015 Aug 19; doi: 10.1177/1043659615600765. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim SS, Kim SH, Ziedonis D. Tobacco dependence treatment for Korean Americans: preliminary findings. J Immigrant Minority Health. 2012;14(3):395–404. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9507-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim YS. Seasonal variation in carbon monoxide poisoning in urban Korea. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1985;39(1):79–81. doi: 10.1136/jech.39.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5(1):13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suinn RM, Rickard-Figueroa K, Lew S, Vigil P. The Suinn-Lew Asian self-identity acculturation scale: an initial report. Educ Psychol Meas. 1987;47(2):401–407. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim SS, Fang H, Difranza J, Ziedonis DM, Ma GX. Gender differences in the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence in Korean Americans. J Smok Cessat. 2012;7(1):1–6. doi: 10.1017/jsc.2012.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Difranza JR, Savageau JA, Wellman RJ. A comparison of the autonomy over tobacco scale and the Fagerström test for nicotine dependence. Addict Behav. 2012;37(7):856–861. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for use in primary care. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psych Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cho MJ, Kim KH. Use of the center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale in Korea. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998;186(5):304–310. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199805000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKee SA, O’Malley SS, Salovey P, Krishnan-Sarin S, Mazure CM. Perceived risks and benefits of smoking cessation: gender-specific predictors of motivation and treatment outcome. Addict Behav. 2005;30(3):423–435. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim SS. Gender differences in perceived risks and benefits of quitting smoking among Korean Americans. Womens Health, Issues and Care. 2014;3:5. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim SS. Predictors of short-term smoking cessation among Korean American men. Public Health Nurs. 2008;25(6):516–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2008.00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim SS, Kim S, Gulick EE. Cross-cultural validation of a smoking abstinence self-efficacy scale in Korean American men. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2009;30(2):122–130. doi: 10.1080/01612840802370582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, Nguyen TD. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: development of a general scale. Eval Program Plann. 1979;2(3):197–207. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(79)90094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benowitz NL, Jacob P., 3rd Metabolism of nicotine to cotinine studied by a dual stable isotope method. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;56(5):483–493. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1994.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ziefle M, Bay S. How older adults meet complexity: aging effects on the usability of different mobile phones. Behav Inf Technol. 2005;24(5):375–389. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meredith SE, Robinson A, Erb P, et al. A mobile-phone-based breath carbon monoxide meter to detect cigarette smoking. Nicotine Tobacco Res. 2014;16(6):766–773. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raiff BR, Faix C, Turturici M, Dallery J. Breath carbon monoxide output is affected by speed of emptying the lungs: implications for laboratory and smoking cessation research. Nicotine Tobacco Res. 2010;12(8):834–838. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]