Abstract

In a context with limited attention to mental health and prevalent sexual prejudice, valid measurements are a key first step to understanding the psychological suffering of sexual minority populations. We adapted the Patient Health Questionnaire as a depressive symptom severity measure for Vietnamese sexual minority women, ensuring its cultural relevance and suitability for internet-based research. Psychometric evaluation found that the scale is mostly unidimensional and has good convergent validity, good external construct validity, and excellent reliability. The sample’s high endorsement of scale items emphasizes the need to study minority stress and mental health in this population.

Keywords: Depression, sexual minority women, lesbian, Viet Nam, scale adaptation, validation

Introduction

Research from North America and Europe provides ample evidence that lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) persons suffer higher rates of psychological distress, depression and suicidality compared to heterosexuals (see meta-analyses by King et al., 2008; Marshal et al., 2011; Meyer, 2003). In Viet Nam, a lower middle-income Asian country, health research with sexual minority populations has mostly been conducted with men who have sex with men, and focused on HIV/AIDS and sexual behavior, with little attention to mental health and sexual stigma (see review by Le, Vu, & Bui, 2012). With increasing visibility of Vietnamese sexual minority populations (Institute for Studies of Society Economy and Environment & Academy of Journalism and Communication, 2010; T. Q. Nguyen et al., 2014), researchers have begun paying attention to broader sexual minority health and well-being and the life context of sexual minority persons. In men who have sex with men, homosexuality-related stigma has recently been examined as a predictor of sexual risk behavior (Ha, Risser, Ross, Huynh, & Nguyen, 2015). In sexual minority women, a qualitative study revealed that encounters with sexual prejudice, especially in the family environment, were common and seemed to cause tremendous psychological distress (T. Q. Nguyen, Nguyen, Le, & Le, 2010). Data on prevalence of mental health problems such as depression and anxiety in Vietnamese sexual minority women or men are not available. However, in a recent survey of sexual minority women, 17.6% reported having attempted suicide, and about half of this group reported having had more than one attempts (T. Q. Nguyen, 2014). This is much higher prevalence compared to the 0.4% or 0.5% reported from general population samples (H. T.-T. Tran, Tran, Jiang, Leenaars, & Wasserman, 2006; Vuong, Van Ginneken, Morris, Ha, & Busse, 2011).

To conduct rigorous research about the mental health and well-being of Vietnamese sexual minority populations, valid and reliable measurement instruments are needed as the first step. This paper is concerned specifically with the measurement of depressive symptom severity. Our review of existing measures led to the decision to adapt and validate the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Spitzer, Kroenke, & Williams, 1999) as a measure of depressive symptom severity for Vietnamese sexual minority women.

Depression-related scales for research of Vietnamese populations

The lack of research attention to sexual minority mental health needs to be put in the broader context in Viet Nam, where mental health research is still limited. In clinical care, there has been attention to common mental disorders (CMD), a grouping that includes depression and anxiety disorders (World Health Organization & Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, 2014), and thus several instruments have been validated and used as screening tools for CMD. Their validation typically involves assessment of criterion validity against diagnosis of a general category of disorders, without focusing on specific disorders. For example, Tran and colleagues identified cut-points on several scales – the Edinburg Postnatal Depression Scale (Cox, Holden, & Sagovsky, 1987), Zung’s Self-rated Anxiety Scale (Zung, 1971) and the General Health Questionnaire (Goldberg & Williams, 1988) – that are predictive of a diagnosis of depression/generalized anxiety/panic disorder (T. D. Tran et al., 2011; T. D. Tran, Tran, & Fisher, 2012); Tuan and colleagues (2004) validated the Self-reporting Questionnaire (World Health Organization, 1994) against diagnosis of any neurotic disorder, and Giang (2006) validated the same instrument against diagnosis of any psychiatric disorder.

Community studies of depression in Viet Nam have used several different scales. Two of these scales were originally developed for Vietnamese refugees, the Vietnamese Depression Scale (VDS) for refugees in the United States (Kinzie et al., 1982) and the Phan Vietnamese Psychiatric Scale (PVPS) for refugees in Australia (Phan, Steel, & Silove, 2004) but their psychometric properties for Vietnamese people living in Viet Nam have not been evaluated. Each scale was used in one applied study, the VDS in studying primary care patients (N.-L. D. Nguyen, Hunt, & Scott, 2005) and the PVPS in studying men living with HIV (Esposito, Steel, Gioi, Huyen, & Tarantola, 2009). In reviewing these scales, our team found that the Vietnamese expressions used in many of the scale items were either outdated or unclear.

A scale which seems more popular is the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CESD-20) (Radloff, 1977), which has been used in studies of people living with HIV (H. M. Do, 2011), medical students (Q. D. Do & Tasanapradit, 2008) and high school students (Huong, Tien, Chi, Quynh Anh, & Phuong, 2010) in Viet Nam. This scale has been adapted and validated by two studies (H. T. Nguyen, Le, & Dunne, 2007; T. Đ. Nguyen & Le, 2010), both in the recent past, using data from Vietnamese adolescent samples. Evaluating the scale’s factor structure and construct validity, these studies established that the CESD-20 is a valid measure of depressive symptom severity.

Research on risk factors, as well as protective factors, of psychological distress, depression and depression-related behaviors (e.g., suicide attempts) in sexual minority populations, requires measures of depressive symptom severity. For example, based on the minority stress model (Meyer, 2003), one could be interested in assessing whether experience of sexual-prejudice-based bullying at school or discrimination at work was associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms, or whether social support moderates this association. While the CESD-20 is an obvious candidate as a measure of depressive symptom severity, its 20-item length is more suitable for in-person interviews. With the increasing use of internet-based survey, especially to reach hard-to-reach populations, instruments that are shorter and can be self-administered are also needed. We therefore adapted and evaluated a shorter scale with good psychometric properties, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Spitzer et al., 1999).

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

The PHQ-9 is a self-administered questionnaire with nine symptom items and a two-week time frame, based on DSM-IV diagnosis criteria for depressive disorders. It can be used to measure symptom severity by summing the items, or to detect probable clinical cases using a symptom-counting algorithm (Spitzer et al., 1999). It has been evaluated in different ethnic groups and many countries (Adewuya, Ola, & Afolabi, 2006; Chen, Huang, Chang, & Chung, 2006; Gilbody, Richards, & Barkham, 2007; C. Han et al., 2008; Huang, Chung, Kroenke, Delucchi, & Spitzer, 2006; Lotrakul, Sumrithe, & Saipanish, 2008; Monahan et al., 2009; Omoro, Fann, Weymuller, Macharia, & Yueh, 2006; Wulsin, Somoza, & Heck, 2002; Yeung et al., 2008; Yu, Tam, Wong, Lam, & Stewart, 2012). The PHQ-9 was found to have a one-factor structure in primary care outpatients (Cameron, Crawford, Lawton, & Reid, 2008; Huang et al., 2006) and in patients with major depression (Williams et al., 2009). Research with special samples including spinal cord injury patients (Kalpakjian et al., 2009; Krause, Bombardier, & Carter, 2008; Richardson & Richards, 2008), heart disease patients (de Jonge, Mangano, & Whooley, 2007) and soldiers (Elhai et al., 2012) found some support for a second somatic factor. Convergent validity of the PHQ-9 is strong, with correlations around 0.67–0.68 or over 0.70 with various other depressive symptoms scales (Adewuya et al., 2006; Cameron et al., 2008; C. Han et al., 2008; Martin, Rief, Klaiberg, & Braehler, 2006). Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) ranged from 0.79 to 0.92 (Adewuya et al., 2006; Cameron et al., 2008; Esler, Johnston, Thomas, & Davis, 2008; C. Han et al., 2008; Hepner, Hunter, Edelen, Zhou, & Watkins, 2009; Hides et al., 2007; Lotrakul et al., 2008; Milette, Hudson, Baron, & Thombs, 2010; Stafford, Berk, & Jackson, 2007).

The present study

This study aimed to adapt and validate the PHQ-9 as a brief measure of depressive symptom severity for Vietnamese sexual minority women. It evaluated the adapted scale’s factor structure, convergent validity, external construct validity, and reliability. Sexual minority women (SMW) are defined in this study as women who are romantically/sexually attracted to, or have romantic/sexual relations with, other women, or who identify as lesbian or bisexual.

Methods

Data source

The study sample was drawn from a web-based anonymous survey conducted in 2012 that targeted SMW. The survey was advertised as Survey of Women who Love Women on six Vietnamese internet forums catering to SMW. Potential respondents were screened using three statements: “You are over 18 years old”, “You are a woman”, and “You have loved another woman (/other women)”. It should be noted that the Vietnamese word “yêu” (love) implies either having had romantic/sexual feelings for, or having been in a relationship with, someone, which corresponds to the study’s broad definition of SMW. Also, the Vietnamese word “nũ” (woman) refers to a person being a woman, but it could also be interpreted to refer to female biological sex, a detail that we come back to shortly when describing this study’s sample restriction. Those who indicated that all three statements were correct were provided with informed consent material including a description of the survey and their rights as (potential) participants, and respondents provided consent before answering the questionnaire. Respondents were not compensated; instead, for each completed questionnaire, a small amount equivalent to 1.44 USD was contributed to an internet forum they selected. The survey was a joint project between Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (JHSPH) and two Vietnamese organizations, the Institute for Studies of Society, Economy and Environment (iSEE, a research and advocacy organization focusing on minority groups including sexual minorities) and ICS Center (an activist organization working for equal rights for LGBT). It was approved by the Institutional Review Board at JHSPH.

Given the fact that transmen mingle with SMW online and offline (and that one of the six internet forums was explicit that it served both SMW and transmen), and given the ambiguity of the second screening statement, it was anticipated that some transmen might enter the survey. In order to separate the two groups, survey respondents were asked about gender identity in the questionnaire. Individuals who chose the answer “I consider myself a man/transguy (even though I was born female)” were excluded from the present study. The sample for the present study was restricted to survey respondents who were SMW and living in Viet Nam (n=2498).

Scale adaptation

The scale was adapted in several steps. First it was examined by Vietnamese members of the study team (two of whom were fluent in English) to determine cultural relevance and suitability for anonymous self-administration, and was adjusted accordingly. Then the scale was translated into Vietnamese by the first author, and the translation was discussed with other Vietnamese researchers at iSEE, which resulted in additional modifications. The modified translation was then examined by staff and volunteers of iSEE and ICS Center who identify as lesbian women. They commented on each item – if they found it hard to understand, how they understood it, if they felt it accurately reflects a feeling or a problem experienced by someone who is sad, and how they would say the same thing better. They also commented on the whole set of items, and on whether new items should be added. Through this process, the scale was further adapted. The adapted scale was independently translated into English by two translators who were blind to the original scale and to the prior translation and adaptation process. The translations were compared, and any discrepancies were discussed and jointly resolved.

Psychometric evaluation

For internal validity, we evaluated the adapted PHQ-9’s factor structure. We started with a simple one-factor confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Goodness-of-fit was evaluated based on chi-square tests, CFI, TLI and RMSEA. Where there was lack of fit, exploratory analysis was conducted using the full sample as well as two half-samples (split by order of survey-starting time), with the aim of finding a better-fitting model that is robust across samples. Exploratory analysis involved adding residual correlations to the model based on modification indices, and examining eigenvalues to see if the data supported a multi-factor structure. All factor analyses were based on polychoric correlations among ordinal indicators.

To evaluate convergent validity, we correlated the scale’s sum score with another measure of depressive symptoms, the CESD-20 (Cronbach’s α = 0.94 in this sample). This was compared to the PHQ-9’s correlations with two measures of anxiety symptoms, the Zung Self-rated Anxiety Scale (Zung-SAS, α=0.90), and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7, α=0.92) (Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & Löwe, 2006). Moderate to strong correlations with anxiety measures were anticipated, because depressive and anxiety symptoms tend to co-occur (Sartorius, Ustün, Lecrubier, & Wittchen, 1996; Schoevers, Deeg, van Tilburg, & Beekman, 2005) and this has been documented in Viet Nam (T. D. Tran, Tran, & Fisher, 2013). Yet we expected such correlations to be smaller than the correlation with the CESD-20, because both instruments measure depressive symptoms.

For external construct validity, we examined the adapted scale’s associations with several other variables: self-rated mood, life satisfaction, self-esteem, self-rated health, lifetime suicide attempt history, income, and residence in a major city. The variable expected to be most correlated with the PHQ-9 is self-rated mood, which was the respondent’s subjective evaluation of her mood “these days” on an ordinal scale from 1=very bad to 6=excellent (similar to the more common single-item measure of self-rated health). Life satisfaction and self-esteem were expected to be moderately correlated with the PHQ-9. The former was measured using the Satisfaction with Life scale (SWLS, α=0.87 in this sample) (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985), reflecting the respondent’s global judgement of satisfaction with her life. Life satisfaction and depressive symptoms are related because they may both be impacted by the same events in life, and a judgment of life satisfaction may also be influenced by the person’s current mood (Pavot & Diener, 2008). The SWLS has been found to be associated (Pearson’s rho −0.49 to −0.57) with depressive symptoms in university students (Schimmack, Oishi, Furr, & Funder, 2004; Tremblay, Blanchard, Pelletier, & Vallerand, 2006) and middle-aged adults (Chang & Sanna, 2001). Self-esteem was measured with the Rosenberg self-esteem scale (α=0.86 in this sample) (Rosenberg, 1965). Self-esteem is considered a coping resource and has been found to reduce depressive and other psychological symptoms and buffer against stress (Thoits, 1995). Social disadvantage, such as experience of family rejection of minority sexual identity (which is associated with depression), can be damaging to self-esteem (Dahl & Galliher, 2010). Correlation between self-esteem and depressive symptoms have been found to be substantial in high stress samples, e.g., −0.42 in unemployed individuals (Shamir, 1986) and −0.67 in sexual minority young adults (Dahl & Galliher, 2010). Self-rated health was expected to be weakly to moderately correlated with the PHQ-9. Associations between depression and self-rated health have been documented in aging populations, with depression being a predictor of poor self-rated health (B Han & Jylha, 2006; B Han, 2002; Lenze et al., 2001; Rodin & McAvay, 1992). While this relationship seems to have not been examined in younger populations, adolescent studies have found that variables negatively related to depression (self-esteem and general well-being) were predictive of self-rated health (Breidablik, Meland, & Lydersen, 2009; Wade, Pevalin, & Vingilis, 2000). Suicide attempt history was expected to have a strong association with depressive symptoms. While income has been found to be associated with depressive symptoms (e.g., in women residing in a Detroit neighborhood, via financial stress (Schulz et al., 2006)), we expected to find a weak – if any – association between income (specifically log monthly income) and depressive symptoms, because in this national sample income was not adjusted for regional costs of living. We did not expect to find an association between residence in a major city and depressive symptoms. The scale’s associations with the continuous variables were assessed using Pearson’s correlation; its association with the binary variables (lifetime suicide attempt and major city residence) were assessed using differences in means.

In addition, we examined the association between these external variables and a binary variable probable depression using odds ratios. Based on the DSM-IV symptom-counting algorithm, this variable takes the value 1 if the respondent is positive for at least one of the first two PHQ-9 items (loss of pleasure and sadness) and positive for a total of at least five items – and 0 otherwise. Items 1 to 8 scored 2 (more than half the days) or 3 (almost everyday) count as positive; item 9 scored 1 (some days) or higher counts as positive.

Because the survey included multiple topics, to avoid respondent fatigue, not all survey sections were administered to all respondents. One section, which included four of the above-described measures (CESD-20, Zung-SAS, SWLS and Rosenberg self-esteem scale), was administered only to the first 300 survey respondents. For the present study, this means these measures were available for only a sub-sample of 214 SMW living in Viet Nam.

Reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s (1951) alpha, which estimates the scale’s internal consistency.

Results

The adapted scale

Before the scale was translated into Vietnamese, one modification was made changing item 9 from “Thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way” to “Thoughts that you would be better off dead.” The “hurting yourself” component of this item implied possible suicidal ideation, which would have activated investigators’ obligation to assess risk and provide crisis management, an obligation we would not have been able to fulfill because the survey was anonymous. Besides, “hurting yourself in some way” could be interpreted to include self-cutting, a behavior that has recently emerged among youth, involving shallow cuts on the body (often the arms), which reportedly provide a kind of pleasure or distraction from psychological pain (Xuân-Hoàng, 2008) but is not necessarily suicidal. Kroenke, one of the authors of the PHQ-9, endorsed this modification (via personal communication), because a systematic review had documented that such modification would not change the psychometric properties of the scale (Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams, & Löwe, 2010).

Discussion with Vietnamese researchers resulted in two other changes. One was to remove the example of “letting family down” from item 6, “Feeling bad about yourself – or that you are a failure or have let yourself or your family down,” because it might be leading, given the study population’s common experience of family rejection (T. Q. Nguyen et al., 2010). We believe that this change did not affect the quality of the item. The other change was to leave out the examples of “reading newspapers or watching television” in item 7 (about having trouble concentrating). These examples were considered not suitable because not everyone reads newspapers, and because watching television is often a household activity involving talking about things on and off the screen, therefore concentration is not something generally expected.

Consultation with iSEE and ICS staff and volunteers (who identify as lesbian women) helped fine-tune the wording of the items so they were clear in language and meaning. In one instance, a phrase was added, in parentheses, to item 1; this phrase – “không thiết làm gì” – is a colloquial expression which means feeling no interest in doing anything. For all modifications, see the adapted scale and original scale in Table 1.

Table 1.

The adapted scale

| Vietnamese version (web-based format) | English translation of Vietnamese version | Original PHQ-9 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| The global question: | |||||||||||||

|

Trong HAI TUẦN vừa qua, bạn có gặp các vấn đề sau không? Với mỗi vấn đề, hãy đánh dấu mức độ bạn gặp phải. Chú ý đừng đánh dấu nhầm vào cột “không muốn trả lời”. |

In the past TWO WEEKS, did you have the following problems? With each problem, please mark the degree you had it. Be careful not to mark “don’t want to answer” by mistake. |

Over the past 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems? (use “✓” to indicate your answer) |

|||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| The items: | |||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Response options: | |||||||||||||

| không hề 0 |

một số ngày 1 |

đa số ngày 2 |

gần như hàng ngày 3 |

không muốn trả lời | not at all 0 |

some days 1 |

more than half the days 2 |

almost every day 3 |

don’t want to answer | not at all | several days | more than half the days | almost every day |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

A question was raised about the double-barreled nature of three items: item 3 combining trouble sleeping and sleeping too much; item 5 combining poor appetite and overeating; and item 8 combining moving/speaking slowly and restlessness. We considered splitting these items each into a pair and using the higher score in each pair as the score for the symptom category; this approach is used in the Major (ICD-10) Depression Inventory (MDI) (Olsen, Jensen, Noerholm, Martiny, & Bech, 2003). However, a review of the PHQ-9 literature did not reveal any study that had tried this method, and thus no data on the agreement (or lack thereof) between the two methods. We therefore decided to use the combined format of the original scale for this validation study and leave the examination of split versus combined formats to a later study.

One person proposed adding an item: “Not feeling like meeting, talking or communicating with others; wanting to withdraw to oneself”. The data show that this item correlated well with other items and with the whole scale. Since it does not seem to add to or subtract from the psychometric properties of the scale, in this paper we only present analyses involving the nine original items.

The survey sample

The sample comprised 2498 SMW. Three-fourths (76.6%) lived in the country’s major cities. The majority was young – 37.2% were 18–20 years old, and 42.5% were 21–25 years old. Half (49.4%) had some university level education, another 33.7% were high school graduates. A substantial proportion (17.5%) reported having ever attempted suicide. Slightly over half (51.8%) of the sample identified as lesbian, 28.9% identified as bisexual, 16.3% reported being unsure about their sexual identity, and a small proportion (2.96%) identified as heterosexual. The presence of this last group was not surprising, as T. Q. Nguyen et al. (2010) found that some women who were in long-term relationships with lesbian women identified as heterosexual.

A summary of item responses and pairwise polychoric correlations are included in Tables 2 and 3. PHQ-9 symptoms were prevalent in this sample. Nearly one fourth of the sample (23.5%) reported loss of pleasure; a similar proportion (23.9%) reported feeling sad/hopeless at the same frequency; and 32.5%, 25.8%, and 22.5% reported having sleeping problems, eating problems and feeling tired/low energy, respectively – all at the frequency of more than half the days or almost everyday in the past two weeks. In addition, 29.2% felt bad about themselves everyday; 11.1% thought they would rather be dead almost everyday, and another 21.9% thought so on some days in the past two weeks.

Table 2.

Response proportions in the full sample (n=2498)

| not at all (0) | some days (1) | more than half the days (2) | almost every day (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. loss of pleasure | 23.2% | 53.3% | 11.6% | 11.9% |

| 2. sad/hopeless | 26.7% | 49.3% | 13.2% | 10.7% |

| 3. sleep problems | 28.5% | 39.0% | 16.3% | 16.2% |

| 4. tired, low energy | 27.7% | 49.8% | 13.0% | 9.5% |

| 5. eating problems | 33.8% | 40.4% | 14.3% | 11.5% |

| 6. feel bad about self | 28.3% | 42.4% | 0% | 29.2% |

| 7. trouble concentrating | 30.3% | 42.6% | 0% | 27.0% |

| 8. move slow/fidget | 66.5% | 23.8% | 0.3% | 9.4% |

| 9. thought of death | 67.0% | 21.9% | 0% | 11.1% |

Table 3.

Pairwise polychoric correlations among scale items

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. loss of pleasure | ||||||||

| 2. sad/hopeless | 0.65 | |||||||

| 3. sleep problems | 0.43 | 0.48 | ||||||

| 4. tired, low energy | 0.55 | 0.65 | 0.56 | |||||

| 5. eating problems | 0.47 | 0.53 | 0.55 | 0.64 | ||||

| 6. feel bad about self | 0.51 | 0.60 | 0.38 | 0.52 | 0.42 | |||

| 7. trouble concentrating | 0.47 | 0.52 | 0.42 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.59 | ||

| 8. move slow/fidget | 0.46 | 0.55 | 0.41 | 0.54 | 0.48 | 0.56 | 0.61 | |

| 9. thought of death | 0.48 | 0.65 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.44 | 0.55 | 0.48 | 0.56 |

Factor structure

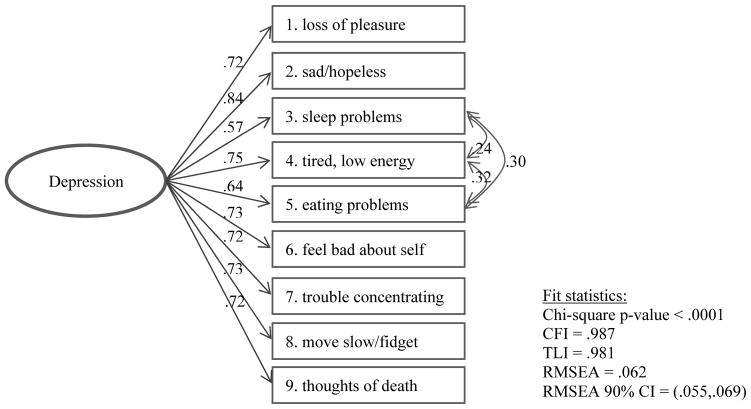

In the a simple one-factor model, the loadings for all items were high (0.64 to 0.82). The chi-square statistic was significant (p-value < 0.0001), suggesting lack of fit. However, this p-value should be interpreted with caution, as the test is sensitive to large sample size (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1993). Using a 0.95 threshold (Hu & Bentler, 1999), CFI=0.970 and TLI=0.959 indicated that the model fit the data well. RMSEA=0.090 suggested not very good fit, but its 95% confidence interval (0.084,0.096) was below the 0.1 poor-fit threshold (MacCallum, Browne, & Sugawara, 1996). Overall, the model had acceptable fit to the data, but the fit could be improved.

Exploratory analysis using modification indices on the full sample led to sequential respecification of the model to allow residual correlations between items 3 (sleep problems) and 5 (eating problems), between items 5 and 4 (low energy), between items 3 and 4, between items 2 (sad/hopeless) and 7 (trouble concentrating), and between items 2 and 8 (slow movement/fidgety). With half-sample 2, exploration led to adding the same residual correlations. For half-sample 1, exploration led to adding only three residual correlations among items 3, 4 and 5. These results combined suggested that the residual correlations among items 3, 4 and 5 were more likely to be robust across different samples than the other residual correlations. The modified one-factor model with only these residual correlations was therefore preferred. Fit to the full sample, this model had excellent CFI (0.987) and TLI (0.981), and an RMSEA of 0.062 (90% CI 0.055 to 0.069) under the 0.08 threshold of reasonable errors of approximation (Browne & Cudeck, 1992).

The residual correlations of items 3, 4 and 5 raised the question whether these somatic items merit a separate factor. However, the data presented only one eigenvalue (5.15) greater than 1 (followed by 0.83, 0.64, 0.52, etc.). The one-factor model with residual correlations among items 3, 4 and 5 was, therefore, the final model.

Convergent validity

The PHQ-9 has good convergent validity with the CESD-20, with Pearson’s correlation between the two sum scores 0.84, 95% CI=(0.80,0.88). This correlation was larger, but only slightly larger, than the PHQ-9’s correlations with the anxiety symptoms scales Zung-SAS [0.80, 95% CI=(0.74,0.84)] and GAD-7 [0.78, 95% CI=(0.77,0.80)].

External construct validity

The left half of Table 4 presents the PHQ-9 sum score’s associations with the external variables considered. These associations were as expected. The score was weakly associated with log-income (correlation −.14) and not associated with big city residence. It was most strongly related to self-rated mood (correlation −.54) as expected, followed by self-esteem (−.50) and life satisfaction (−.44), and had a lower correlation with self-rated health (−.30). A history suicide attempt was associated with a mean score that is 2.58 points higher.

Table 4.

Associations with external constructs/variables of PHQ-9 sum score (left) and PHQ-9-based probable depression (right)

| PHQ-9 sum score | PHQ-9-based probable depression | |

|---|---|---|

| Pearson’s correlation (95% CI) | odds ratio per SDb (95% CI) | |

|

|

||

| Self-rated mood | −.54 (−.57,−.51) | 0.23 (0.20,0.27) |

| Self-esteem | −.50 (−.59,−.39) | 0.39 (0.26,0.57) |

| Satisfaction with lifea | −.44 (−.54,−.33) | 0.45 (0.30,0.64) |

| Self-rated healtha | −.30 (−.33,−.26) | 0.54 (0.48,0.61) |

| Log-income | −.14 (−.18,−.10) | 0.75 (0.67,0.83) |

|

| ||

| difference in means (95% CI) | odds ratio (95% CI) | |

|

|

||

| Ever vs. never attempted suicide | 2.58 (1.74,3.42) | 2.11 (1.56,2.85) |

| Big city vs. not | −0.51 (−1.11,0.08) | 0.89 (0.71,1.13) |

CI = confidence interval; SD = standard deviation.

These scales were only administered to a sub-sample (n=214).

These are odds ratios of probable depression associated with one SD difference in the external variable.

The right half of Table 4 presents odds ratios of probable depression associated with the external variables. The trend of association is similar to that for the sum score.

Reliability

The scale had strong internal consistency: Cronbach’s alpha was 0.86.

Discussion

In this study, we translated and adapted the PHQ-9 to the population of Vietnamese SMW, while maintaining the key contents of the original scale to ensure comparability with international versions as well as applicability to general Vietnamese women. We then evaluated the scale as a measure of depressive symptom severity. Statistical analyses found that the adapted scale is unidimensional with limited item residual correlations as expected, and has good convergent validity, good external construct validity and excellent reliability. In addition, this scale version is easy to understand and takes only a few minutes to complete, which makes it suitable for use in research that requires self-administration (including but not limited to internet-based research). It will play an important role in several ongoing and planned studies by our team examining risk and protective factors for mental health among Vietnamese SMW.

Since the adapted scale uses general wording without specific reference to the sexual minority experience, it is important to note that its applicability is not restricted to Vietnamese SMW, and that it can be used for Vietnamese women in general. In addition, given its non-gender-specific language, and given the PHQ-9’s good track record in different countries and cultures with both men and women, we believe that this scale version is generalizable to Vietnamese sexual minority men and Vietnamese men in general, and recommend it be evaluated in a male sample.

This newly adapted scale adds to the still limited repertoire of mental health scales available in Vietnamese. Similar to the CESD-20, the adapted PHQ-9 can be used in research using depressive symptom severity as a variable (e.g., an outcome caused by social disadvantage and structural injustice, or an antecedent of a health or social outcome); our study established its validity for this purpose. As it is a short scale and can be self-administered, the adapted PHQ-9 could potentially be explored for use as a screening tool (e.g., in a general primary care setting or in a counseling center for LGB) that would alert providers to conduct further assessment. To establish the scale as a screening tool, validation against clinical diagnosis would be needed. This type of assessment in other settings has generally found support for using the PHQ-9 as a screening tool for major depressive disorder (for examples, see Kroenke & Spitzer, 2002; Lotrakul et al., 2008; Wulsin et al., 2002).

Regarding the PHQ-9 scale itself (not specific to the adapted version), our study identified two aspects that may benefit from further consideration and research. The first is the double-barreled nature of three items. While we did not modify the scale to address this issue, we recognize that this could make it harder for respondents to process the items. Whether and how this affects measurement should be explored in further research. The second aspect concerns somatic symptoms in the scale’s factor structure. Reports of a two-factor structure for the PHQ-9 have mostly come from populations characterized by a physical illness or injury. In our sample (which is not characterized by a physical illness or injury) we found best support for a one-factor structure with residual correlations among somatic symptoms. Also, despite these residual correlations, the simple sum score was a good proxy for the underlying depression factor (as it has good convergent validity with the CESD-20). However, future research of the PHQ-9 should examine when a minor somatic factor (influencing somatic symptoms) may be needed in addition to the primary depression factor (influencing all items) to avoid confounding depression. In samples with severe physical illness, correlations among somatic items could be partially caused by the physical condition.

Turning our attention to the well-being of the study population, the sample’s high endorsement of scale items (e.g., about one fourth felt sad/hopeless for more than half the days or nearly every day, and 11% thought they would rather be dead nearly everyday, in the past two weeks) strongly suggests this population has high exposure to stress. This is consistent with the pervasive experience of family disapproval and negative treatment (T. Q. Nguyen et al., 2014, 2010) and the high prevalence of lifetime suicide attempt (T. Q. Nguyen, 2014) documented in this population. Further work examining the relationships between family rejection, depressive symptoms and suicidality should be conducted, which in the context of Viet Nam would be useful contribution to the ongoing efforts by activist groups, including ICS and a newly formed group of parents of LGBT, in fighting stigma and promoting support within families. Besides family rejection, the prevalence and the harms of other forms of sexual prejudice, such as bullying and discrimination (which anecdotal evidence suggests are commonplace), need to be examined. In addition, other components of minority stress in this population, including internalized homophobia, concealment of sexual minority status (Meyer, 2003) and anticipation of heterosexual marriage either for oneself or one’s female partner (T. Q. Nguyen et al., 2010), need to be studied. Protective factors that increase resiliency in the face of minority stress in the Vietnamese context are another important area for research. This study, which validated a depressive symptom scale, is a first step in laying the groundwork for a research agenda that helps inform the design, targeting and implementation of interventions to protect the health, well-being and lives of sexual minority populations in Viet Nam.

Figure 1.

The final factor model

Acknowledgments

Survey expenses were covered by the Institute for Studies of Society, Economy and Environment (iSEE) and Department of Health, Behavior and Society at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (JHSPH). TQN’s work on this project was supported by the Sommer Scholarship Program (via a scholarship for her doctoral training) and NIH grant T-32DA007292 (via a postdoctoral research fellowship, PI C. Debra M. Furr-Holden). The authors are grateful for iSEE/ICS Center staff’s (especially Nguyễn Hải Yến’s and Vũ Kiều Châu Loan’s) and volunteers’ contributions to survey development and implementation; the internet forums’ support in promoting the survey; the participation of and information shared by all survey respondents; translation support by Võ Thị Châu Giang and Nguyễn Thị Linh Vân; and editing support by QuynhTrang Phuong Nguyen. The authors thank the Reviewers and Associate Editor for feedback that helped them improve the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- Adewuya AO, Ola BA, Afolabi OO. Validity of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) as a screening tool for depression amongst Nigerian university students. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;96(1–2):89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breidablik HJ, Meland E, Lydersen S. Self-rated health during adolescence: Stability and predictors of change (Young-HUNT study, Norway) European Journal of Public Health. 2009;19(1):73–78. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckn111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research. 1992;21(2):230–258. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron IM, Crawford JR, Lawton K, Reid IC. Psychometric comparison of PHQ-9 and HADS for measuring depression severity in primary care. The British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 2008;58(546):32–6. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X263794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EC, Sanna LJ. Optimism, pessimism, and positive and negative affectivity in middle-aged adults: a test of a cognitive-affective model of psychological adjustment. Psychology and Aging. 2001;16(3):524–531. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.16.3.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TM, Huang FY, Chang C, Chung H. Using the PHQ-9 for depression screening and treatment monitoring for Chinese Americans in primary care. Psychiatric Services (Washington, DC) 2006;57(7):976–81. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.7.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;150(6):782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16(3):297–334. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl A, Galliher R. Sexual Minority Young Adult Religiosity, Sexual Orientation Conflict, Self-Esteem and Depressive Symptoms. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health. 2010;14(4):271–290. [Google Scholar]

- De Jonge P, Mangano D, Whooley Ma. Differential association of cognitive and somatic depressive symptoms with heart rate variability in patients with stable coronary heart disease: findings from the Heart and Soul Study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69(8):735–9. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815743ca. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49(1):71–5. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do HM. Doctoral Dissertation. Queensland University of Technology; 2011. Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) Adherence among People Living with HIV/AIDS (PLHIV) in the North of Vietnam: A Multi-method Approach. [Google Scholar]

- Do QD, Tasanapradit P. Depression and stress among the first year medical students in University of Medicine and Pharmacy, HoChiMinh City, Vietnam. Journal of Health Research. 2008;22(suppl):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Elhai JD, Contractor Aa, Tamburrino M, Fine TH, Prescott MR, Shirley E, … Calabrese JR. The factor structure of major depression symptoms: a test of four competing models using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Psychiatry Research. 2012;199(3):169–73. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esler D, Johnston F, Thomas D, Davis B. The validity of a depression screening tool modified for use with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2008;32(4):317–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2008.00247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito CA, Steel Z, Gioi TM, Huyen TTN, Tarantola D. The prevalence of depression among men living with HIV infection in Vietnam. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(Suppl 2):S439–44. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.155168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giang KB. The Vietnamese version of the Self Reporting Questionnaire 20 (SRQ-20) in detecting mental disorders in rural Vietnam: A validation study. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2006;52(2):175–184. doi: 10.1177/0020764006061251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbody S, Richards D, Barkham M. Diagnosing depression in primary care using self-completed instruments: UK validation of PHQ–9 and CORE–OM. British Journal of General Practice. 2007;57:650–652. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg D, Williams P. A user’s guide to the General Health Questionnaire, NFER-Nelson, Windsor. Windsor: NFER-Nelson; 1988. Retrieved from http://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=related:TQ7O72p22AoJ:scholar.google.com/&hl=en&as_sdt=0,9#0. [Google Scholar]

- Ha H, Risser JMH, Ross MW, Huynh NT, Nguyen HTM. Homosexuality-related stigma and sexual risk behaviors among men who have sex with men in Hanoi, Vietnam. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2015;44:349–356. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0450-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B. Depressive symptoms and self-rated health in community-dwelling older adults: a longitudinal study. Journal of Americal Geriatric Society. 2002;50:1549–1556. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B, Jylha M. Improvement in depressive symptoms and changes in self-rated health among community-dwelling disabled older adults. Aging & Mental Health. 2006;10(6):599–605. doi: 10.1080/13607860600641077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C, Jo SA, Kwak JH, Pae CU, Steffens D, Jo I, Park MH. Validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Korean version in the elderly population: the Ansan Geriatric study. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2008;49(2):218–23. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepner Ka, Hunter SB, Edelen MO, Zhou AJ, Watkins K. A comparison of two depressive symptomatology measures in residential substance abuse treatment clients. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;37(3):318–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hides L, Lubman DI, Devlin H, Cotton S, Aitken C, Gibbie T, Hellard M. Reliability and validity of the Kessler 10 and Patient Health Questionnaire among injecting drug users. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;41(2):166–8. doi: 10.1080/00048670601109949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Huang FY, Chung H, Kroenke K, Delucchi KL, Spitzer RL. Using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 to Measure Depression among Racially and Ethnically Diverse Primary Care Patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:547–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huong NT, Tien TQ, Chi HK, Quynh Anh N, Phuong NH. Some mental health problems and influential factors of secondary school students in Hanoi, Vietnam. Journal of Science, Hue University. 2010;61:215–224. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Studies of Society Economy and Environment, & Academy of Journalism and Communication. Sending The Wrong Message: The Portrayal of Homosexuality in the Vietnamese Printed and Online Press. Ha Noi, Viet Nam: Thế Giới Publishers; 2010. Retrieved from http://www.isee.org.vn/Content/Home/Library/lgbt/sending-the-wrong-messages-the-portrayal-of-homosexuality-in-the-vietnamese-printed-and-online-press.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. LISREL 8: Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language. Chicago: Scientific Software International; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kalpakjian CZ, Toussaint LL, Albright KJ, Bombardier CH, Krause JK, Tate DG. Patient health Questionnaire-9 in spinal cord injury: an examination of factor structure as related to gender. The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine. 2009;32(2):147–56. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2009.11760766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King M, Semlyen J, Tai SS, Killaspy H, Osborn D, Popelyuk D, Nazareth I. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzie JD, Manson SM, Vinh DT, ToLan NT, Anh B, Pho TN. Development and validation of a Vietnamese-language depression rating scale. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1982;139(10):1276–1281. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.10.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause JS, Bombardier C, Carter RE. Assessment of depressive symptoms during inpatient rehabilitation for spinal cord injury: Is there an underlying somatic factor when using the PHQ? Rehabilitation Psychology. 2008;53(4):513–520. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric Annals. 2002;32(9):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Löwe B. The Patient Health Questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: A systematic review. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):345–59. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le GM, Vu VD, Bui HT-M. Sexual health and men who have sex with men in Vietnam: An integrated approach to preventive health care. Advances in Preventive Medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/796192. 796192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lenze EJ, Miller MD, Dew Ma, Martire LM, Mulsant BH, Begley aE, … Reynolds CF. Subjective health measures and acute treatment outcomes in geriatric depression. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2001;16:1149–1155. doi: 10.1002/gps.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotrakul M, Sumrithe S, Saipanish R. Reliability and validity of the Thai version of the PHQ-9. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods. 1996;1(2):130–149. [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Dietz LJ, Friedman MS, Stall RD, Smith HA, McGinley J, … Brent DA. Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: A meta-analytic review. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;49(2):115–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A, Rief W, Klaiberg A, Braehler E. Validity of the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire Mood Scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2006;28(1):71–7. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(5):674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milette K, Hudson M, Baron M, Thombs BD. Comparison of the PHQ-9 and CES-D depression scales in systemic sclerosis: internal consistency reliability, convergent validity and clinical correlates. Rheumatology. 2010;49(4):789–96. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monahan PO, Shacham E, Reece M, Kroenke K, Ong’or WO, Omollo O, … Ojwang C. Validity/reliability of PHQ-9 and PHQ-2 depression scales among adults living with HIV/AIDS in western Kenya. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24(2):189–97. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0846-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HT, Le VA, Dunne M. Giá trị và độ tin cậy của hai thang đo trầm cảm và lo âu sử dụng trong nghiên cứu cộng đồng đối với đối tượng vị thành niên [Validity and reliability of two depression and anxiety scales for use in community research with adolescents] Tạp Chí Y Tế Công Cộng. 2007;7(7):25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen NLD, Hunt DD, Scott CS. Screening for depression in a primary care setting in Vietnam. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2005;193(2):144–147. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000152811.72059.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TĐ, Le LC. Giá trị, độ tin cậy của thang đo trầm cảm của vị thành niên và thanh niên và một số yếu tố liên quan tại huyện Chí Linh, Hải Dương năm 2006 [Validity and reliability of a depression scale for adolescents and correlates in Chi Linh district, Hai Duong province in 2006] Tạp Chí Y Tế Công Cộng. 2010;16(16):33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TQ. Tóm tắt kết quả khảo sát nũ yêu nũ 2012 về sự đối xử tiêu cực của gia đình đối với người nũ yêu nũ và người chuyển giới và mối liên hệ với sức khỏe tâm trí, và câu hỏi đặt ra về vai trò tiềm năng của bác sĩ. Summary of findings from the 2012 Women Who Love Women about negative family treatment of women who love women and of transmen, and its associations with mental health; and a question about potential roles of the physician; Presentation at the Mental Health Risks of Sexual and Gender Minority Populations Workshop, Institute for Studies of Society, Economy and Environment; Ha Noi, Viet Nam. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TQ, Bandeen-Roche K, Masyn KE, German D, Nguyen YH, Vu LK-C, Knowlton AR. Negative family treatment of sexual minority women and transmen in Vietnam: Latent classes and their predictors. Journal of GLBT Family Studies. 2014 doi: 10.1080/1550428X.2014.964443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TQ, Nguyen NTT, Le TNT, Le BQ. Sống trong một xã hội dị tính: Câu chuyện từ 40 người nũ yêu nũ: Quan hệ với cha mẹ [Living in a heterosexual society: Stories from 40 women who love women: Relationships with parents] Ha Noi, Viet Nam: Institute for Studies of Society, Economy and Environment; 2010. Retrieved from http://www.isee.org.vn/Content/Home/Library/lgbt/song-trong-mot-xa-hoi-di-tinh-cau-chuyen-tu-40-nguoi-nu-yeu-nu-quan-he-voi-cha-me.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen LR, Jensen DV, Noerholm V, Martiny K, Bech P. The internal and external validity of the Major Depression Inventory in measuring severity of depressive states. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33(2):351–356. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omoro SAO, Fann JR, Weymuller EA, Macharia IM, Yueh B. Swahili translation and validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 depression scale in the Kenyan head and neck cancer patient population. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2006;36(3):367–81. doi: 10.2190/8W7Y-0TPM-JVGV-QW6M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavot W, Diener E. The satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2008;3(2):137–152. [Google Scholar]

- Phan T, Steel Z, Silove D. An ethnographically derived measure of anxiety, depression and somatization: The Phan Vietnamese Psychiatric Scale. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2004;41(2):200–232. doi: 10.1177/1363461504043565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson EJ, Richards JS. Factor structure of the PHQ-9 screen for depression across time since injury among persons with spinal cord injury. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2008;53(2):243–249. [Google Scholar]

- Rodin J, McAvay G. Determinants of change in perceived health in a longitudinal study of older adults. Journal of Gerontology. 1992;47(6):P373–P384. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.6.p373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Sartorius N, Ustün TB, Lecrubier Y, Wittchen HU. Depression comorbid with anxiety: results from the WHO study on psychological disorders in primary health care. The British Journal of Psychiatry Supplement. 1996;30:38–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimmack U, Oishi S, Furr RM, Funder DC. Personality and life satisfaction: A facet-level analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30:1062–1075. doi: 10.1177/0146167204264292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoevers RA, Deeg DJH, van Tilburg W, Beekman ATF. Depression and generalized anxiety disorder: Co-occurrence and longitudinal patterns in elderly patients. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;13(1):31–39. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz AJ, Israel Ba, Zenk SN, Parker Ea, Lichtenstein R, Shellman-Weir S, Klem aBL. Psychosocial stress and social support as mediators of relationships between income, length of residence and depressive symptoms among African American women on Detroit’s eastside. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62:510–522. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamir B. Self-esteem and the psychological impact of unemployment. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1986;49(1):61. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166(10):1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford L, Berk M, Jackson HJ. Validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 to screen for depression in patients with coronary artery disease. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2007;29(5):417–24. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Stress, coping, and social support processes: Where are we? What next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;35(Extra Issue):53–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran HTT, Tran NT, Jiang GX, Leenaars A, Wasserman D. Life time suicidal thoughts in an urban community in Hanoi, Vietnam. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:76. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran TD, Tran T, Fisher J. Validation of three psychometric instruments for screening for perinatal common mental disorders in men in the north of Vietnam. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;136(1–2):104–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran TD, Tran T, Fisher J. Validation of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) 21 as a screening instrument for depression and anxiety in a rural community-based cohort of northern Vietnamese women. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):24. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran TD, Tran T, La B, Lee D, Rosenthal D, Fisher J. Screening for perinatal common mental disorders in women in the north of Vietnam: a comparison of three psychometric instruments. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;133(1–2):281–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay Ma, Blanchard CM, Pelletier LG, Vallerand RJ. A dual route in explaining health outcomes in natural disaster. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2006;36:1502–1522. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan T, Harpham T, Huong N. Validity and reliability of the self-reporting questionnaire 20 items in Vietnam. Hong Kong Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;14(3):15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Vuong DA, Van Ginneken E, Morris J, Ha ST, Busse R. Mental health in Vietnam: Burden of disease and availability of services. Asian Journal of PSychiatry. 2011;4(1):65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade TJ, Pevalin DJ, Vingilis E. Revisiting student self-rated physical health. Journal of Adolescence. 2000;23(6):785–91. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RT, Heinemann AW, Bode RK, Wilson CS, Fann JR, Tate DG. Improving measurement properties of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 with rating scale analysis. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2009;54(2):198–203. doi: 10.1037/a0015529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. A user’s guide to the self reporting questionnaire (SRQ) Geneva: World Health Organization; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, & Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. Social determinants and mental health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. Retrieved from http://www.stress-burnout.ch/Flyer_Buch_2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Wulsin L, Somoza E, Heck J. The Feasibility of Using the Spanish PHQ-9 to Screen for Depression in Primary Care in Honduras. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2002;4(5):191–195. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v04n0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuân-Hoàng. Trào lưu teen cắt tay hành xác [The trend of arm-cutting among teens] Ngôi Sao. 2008 Retrieved from http://ngoisao.net/tin-tuc/24h/2008/05/trao-luu-teen-cat-tay-hanh-xac-97561/

- Yeung A, Fung F, Yu SC, Vorono S, Ly M, Wu S, Fava M. Validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for depression screening among Chinese Americans. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2008;49(2):211–7. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Tam WWS, Wong PTK, Lam TH, Stewart SM. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for measuring depressive symptoms among the general population in Hong Kong. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2012;53(1):95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971;12(6):371–9. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(71)71479-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]