Abstract

Purpose

We evaluated the activity of regorafenib, an oral multikinase inhibitor, in advanced gastric adenocarcinoma.

Patients and Methods

We conducted an international (Australia and New Zealand, South Korea, and Canada) randomized phase II trial in which patients were randomly assigned at a two-to-one ratio and stratified by lines of prior chemotherapy for advanced disease (one v two) and region. Eligible patients received best supportive care plus regorafenib 160 mg or matching placebo orally on days 1 to 21 of each 28-day cycle until disease progression or prohibitive adverse events occurred. The primary end point was progression-free survival (PFS). Final analysis included data to December 31, 2014.

Results

A total of 152 patients were randomly assigned from November 7, 2012, to February 25, 2014, yielding 147 evaluable patients (regorafenib, n = 97; placebo, n = 50). Baseline characteristics were balanced. Median PFS significantly differed between groups (regorafenib, 2.6 months; 95% CI, 1.8 to 3.1 and placebo, 0.9 months; 95% CI, 0.9 to 0.9; hazard ratio [HR], 0.40; 95% CI, 0.28 to 0.59; P < .001). The effect was greater in South Korea than in Australia, New Zealand, and Canada combined (HR, 0.12 v 0.61; interaction P < .001) but consistent across age, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, primary site, lines of chemotherapy, peritoneal metastasis presence, number of metastatic sites, and plasma vascular endothelial growth factor A. A survival trend in favor of regorafenib was seen (median, 5.8 months; 95% CI, 4.4 to 6.8 v 4.5 months; 95% CI, 3.4 to 5.2; HR, 0.74; P = .147). Twenty-nine patients assigned to placebo received open-label regorafenib after disease progression. Regorafenib toxicity was similar to that previously reported.

Conclusion

In this phase II trial, regorafenib was effective in prolonging PFS in refractory advanced gastric adenocarcinoma. Regional differences were found, but regorafenib was effective in both regional groups. A phase III trial is planned.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric adenocarcinoma is the fifth most common cancer worldwide but the second leading cause of cancer death (8.8% of cancer deaths).1 Five-year survival for advanced gastric cancer (GC) is less than 7%, and median overall survival (OS) is less than 1 year.2 In patients with GC and good performance status, first-line chemotherapy improves OS and quality of life (QoL) compared with best supportive care.2 Outcomes after failure of first-line treatment remain poor. At the time this study was planned, data were emerging for benefit from second-line chemotherapy.3-5 No therapy had demonstrated benefit after failure or intolerance of second-line therapy. Therefore, the treatment of refractory GC is an area of unmet clinical need.

Tumor angiogenesis has been identified as a therapeutic target in GC. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a critical regulator of pathologic angiogenesis6 and is expressed in tumor tissue and peripheral blood as VEGF isoforms (A, B, C, and D) and receptors VEGF-R1 (also known as Flt-1) and VEGF-R2 (Flk/FDR).7 VEGF induces biologic effects, including endothelial cell mitogenesis and migration, induction of proteinases leading to remodeling of the extracellular matrix, permeability of the vasculature, and maintenance of survival of newly formed blood vessels.6 In GC, as in most other cancers, VEGF expression or pathway upregulation predicts poor prognosis.8,9

Agents targeting VEGF and its receptors have been evaluated in clinical trials. In AVAGAST (Avastin in Gastric Cancer), a randomized phase III trial of bevacizumab (anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody) with chemotherapy in GC, bevacizumab improved the secondary efficacy end points of progression-free survival (PFS; 6.7 v 5.3 months; hazard ratio [HR], 0.80; P = .004) and overall response rate (46% v 37%; P = .03) but not the primary end point of OS.10 Phase II studies of VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors sunitinib11 and sorafenib12 have suggested some activity in GC. Although blood-based angiogenic factors are associated with prognosis, identification of a reliable predictive biomarker for antiangiogenic therapy remains elusive.13 In AVAGAST, the group of patients with high baseline plasma VEGF-A levels showed a trend toward improved OS (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.57 to 0.93) compared with the group with low VEGF-A levels (HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.77 to 1.31; interaction P = .07).14

Regorafenib (BAY 73-4506) is an oral multikinase inhibitor with a distinct profile, targeting angiogenic (VEGF-R1, VEGF-R2, and TIE-2), stromal (platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta), and oncogenic (RAF, RET, and KIT) receptor tyrosine kinases. In phase III studies, efficacy has been demonstrated in refractory GI stromal tumors15 and colorectal cancer.16 The purpose of the INTEGRATE (RandomIzed phase II double-bliNd placebo-conTrolled study of rEGorafenib in refRacTory advanced Esopgago-gastric cancer [AOGC]) study was to determine whether regorafenib had sufficient activity and safety to warrant further evaluation in a phase III trial in refractory GC.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design and Participants

INTEGRATE was a double-blind phase II trial in which patients were randomly assigned to either an active arm with regorafenib administered in the context of a conventional single-arm Simon’s two-stage trial design or a calibration arm with placebo (statistical design details provided in the Appendix, online only). Eligible patients were recruited from 53 centers in four countries (Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group: Australia and New Zealand; National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group: Canada and South Korea) between November 2012 and February 2014. Inclusion criteria were as follows: age 18 years or older, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 to 1, metastatic or locally recurrent GC (esophagogastric junction or stomach, adenocarcinoma, or undifferentiated histology) measurable according to RECIST (version 1.1) by computed tomography scan within 21 days before random assignment, and recurrent or metastatic disease refractory to two or fewer lines of chemotherapy (including prior fluoropyrimidine and platinum). Major exclusions were poorly controlled hypertension, prior anti-VEGF therapy, and uncontrolled CNS disease (detailed criteria are provided in the protocol).

All participants provided written informed consent according to International Conference on Harmonisation and Good Clinical Practice and national or local regulations. The protocol was approved by the human research ethics committee of each participating institution, and the trial was prospectively registered.

Random Assignment and Masking

Random assignment was performed centrally via a Web-based system at a ratio of two to one (regorafenib to placebo) and stratified by lines of prior chemotherapy for advanced disease (one v two) and geographic region (Australia, New Zealand, or Canada v South Korea) using a permuted-blocks method and maintaining allocation concealment. An independent statistician monitored the random assignment system. Regorafenib and matching placebo were provided by the manufacturer (Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Whippany, NJ) to sites in kits of three equivalent bottles of 30 tablets each, labeled with unique kit numbers, which were assigned to patients on random assignment.

Procedures

Baseline assessments occurred before random assignment. Safety investigations, including blood tests, occurred before commencement of each treatment cycle at least, with more frequent assessment of liver function and blood pressure in the first 8 weeks. Response was evaluated by computed tomography scan of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis every 4 weeks until week 8, every 6 weeks until week 24, then every 8 weeks thereafter until disease progression or death, timed from the date of random assignment, with scan frequency on the basis of a priori expected PFS. Responses were assessed locally using RECIST (version 1.1) criteria. Blinded central review of all RECIST source documents was undertaken for all patients for date of progression, and 13% of patients were randomly selected for blinded central review by two independent radiologists. QoL assessments were conducted using the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaires (QLQ) C3017 and QLQ-STO2218 and the EuroQol EQ-5D questionnaire19; for participants in Australia and New Zealand, the patient DATA form was also used.20 QoL was to be assessed on day 1 of each cycle up to the visit where disease progression was determined.

Blood for biomarkers (10-mL no-anticoagulant and 10-mL EDTA blood collection tubes) was collected at baseline and on day 1 of cycles two and four. Specimens were centrifuged (1,000 × g [approximately 2,500 rpm] at 4°C for 10 minutes) to obtain platelet-free serum and then aliquoted into cryovials and stored in a cold freezer (−70°C). Plasma VEGF-A (isoforms 121 and 165) was evaluated using multiplex immunoassays (Bio-Plex; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All samples were assayed in duplicate, and the relevant absorbance was measured using the Bio-Plex 200 system multiwell plate reader (Bio-Rad). Analyte concentrations were calculated from a five-parameter logistic curve of the assay standards using Bio-Plex Manager software (Bio-Rad).21

Regorafenib or placebo was self administered by participants at 160 mg (four 40-mg tablets) orally once per day on days 1 to 21 of each 28-day cycle until progression or prohibitive toxicity (on the basis of previous phase III studies). Two dose-level modifications for toxicity (to 120 and 80 mg) were allowed. Dose re-escalation was not permitted except in the event of reversible palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia, hypertension, or deranged AST or ALT. Both treatment groups received best supportive care, defined as any intervention to preserve comfort and dignity. Treatment after discontinuation of study treatment occurred at the investigator’s discretion, with follow-up until death. Patients receiving placebo who were subsequently unblinded because of documented disease progression were able to receive open-label regorafenib provided they continued to meet protocol-specified safety and performance status criteria.

Outcomes

The primary end point was PFS in the regorafenib arm. Patients who commenced nonprotocol anticancer therapy without prior evidence of progression were censored at that time point. Secondary end points included: objective tumor response (by RECIST criteria), clinical benefit status at 2 months (defined as receiving treatment and remaining progression free during weeks 6 to 10), OS, adverse events (AEs; according to National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events [version 4.0]), and QoL.

Sample Size

For sample size calculation in the regorafenib arm, a reference PFS rate for the target population of 50% at 2 months was considered plausible, and an increase to 66% with regorafenib was considered to be of clinical interest. The detailed rationale for a sample size of 150 patients randomly assigned at a two-to-one ratio (regorafenib to placebo) is presented in the Appendix. In summary, the design provided 90% power at a 5% level of significance to reject the null hypothesis of a 2-month PFS probability of 50% or less if the true probability was at least 66%.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were prespecified in a statistical analysis plan finalized before unblinding and included all events to December 31, 2014. Because this was a phase II trial, the primary analysis set (labeled the efficacy analysis set) comprised patients deemed eligible on blinded central clinical review.

Median PFS and OS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and log-rank tests were performed, stratified by region and lines of prior chemotherapy for advanced disease (nonstratified log-rank tests provided comparable results). Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate the HR associated with treatment and to evaluate the consistency of HRs across prespecified covariates (ie, subgroups). The proportional hazards assumption was verified for all models presented. The robustness of the findings was assessed in sensitivity analyses that involved: including all randomly assigned patients and adjusting for prespecified covariates in univariable and multivariable models. A stepwise selection approach was used to construct the multivariable models from the full model comprising main-effect terms for all prespecified covariates.

Data on QoL during treatment were analyzed using a mixed model for repeated measures, with the baseline value, treatment allocation, time point, and time point–by–treatment allocation interaction fitted as covariates. A two-sided alpha of 5% was used to calculate CIs and determine P values. SAS software (version 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for data analysis.

Direct comparison between randomly assigned groups was intended to be exploratory. However, it was given more emphasis after PFS in the placebo arm was found to be considerably less than the benchmark specified at the time the study was designed (ie, a 2-month PFS probability of 50%).

RESULTS

Of the 152 randomly assigned patients, five were subsequently found to be ineligible, and 147 were eligible for inclusion in the efficacy analysis set; 97 were allocated to regorafenib and 50 to placebo (Fig 1). The groups were balanced at baseline (Table 1). The mean age was 60 years; 80% were men; and 37% were from South Korea, 52% from Australia or New Zealand, and 11% from Canada. The primary tumor locations were esophagogastric junction (38%), stomach (58%), and other (4%). Patients had been exposed to either one (42%) or two lines (58%) of prior chemotherapy. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status was 0 (42%) or 1 (58%). Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) status was known in 85 patients (56%), but only six received trastuzumab (Herceptin; Roche, Basel, Switzerland; 4%).

Fig 1.

CONSORT diagram.

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Regorafenib (n = 97) | Placebo (n = 50) | |

| Region | ||

| South Korea | 35 (36) | 19 (38) |

| Australia, New Zealand, and Canada | 62 (64) | 31 (62) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 19 (20) | 10 (20) |

| Male | 78 (80) | 40 (80) |

| Age, years | ||

| Median | 63 | 62 |

| Range | 33-81 | 32-85 |

| Primary site | ||

| Esophagogastric junction | 37 (38) | 19 (38) |

| Stomach or other* | 60 (62) | 31 (62) |

| Lines of therapy | ||

| 1 | 41 (42) | 21 (42) |

| 2 | 56 (58) | 29 (58) |

| ECOG performance status | ||

| 0 | 41 (42) | 21 (42) |

| 1 | 56 (58) | 29 (58) |

| Site of metastasis | ||

| Liver | 49 (51) | 30 (60) |

| Distant lymph node | 50 (52) | 25 (50) |

| Lung | 19 (20) | 11 (22) |

| Peritoneum | 28 (29) | 19 (38) |

| Bone | 11 (11) | 5 (10) |

| Other | 38 (39) | 15 (30) |

| No. of sites with metastatic disease | ||

| 0 | 1 (1) | 2 (4) |

| 1 | 32 (33) | 10 (20) |

| 2 | 36 (37) | 23 (46) |

| 3 | 22 (23) | 11 (22) |

| 4 | 5 (5) | 4 (8) |

| 5 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| HER2 status | ||

| Unknown | 45 (46) | 17 (34) |

| Known | 52 (54) | 33 (66) |

| IHC positive (3+) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) |

| IHC equivocal (2+) | 4 (4) | 3 (6) |

| ISH amplification | 4 (4) | 2 (4) |

| Prior trastuzumab use | 3 (3) | 3 (6) |

| Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio | ||

| < 3 | 50 (52) | 21 (42) |

| ≥ 3 | 47 (48) | 29 (58) |

| Plasma VEGF-A, pg/mL† | ||

| ≤ 0.14 (median) | 56 (58) | 26 (54) |

| > 0.14 | 40 (42) | 22 (46) |

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; IHC, immunohistochemistry; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

Esophagogastric junction, stomach, pylorus of stomach, center at posterior wall of antrum (×2), multifocal distal esophageal adenocarcinoma, or pyloric antrum.

Values below the limit of quantification were assigned the minimum quantitative value recorded (ie, 0.14). Denominator for percentages is 96 for regorafenib and 48 for placebo.

The Kaplan-Meier estimate of median follow-up was 17.1 months (95% CI, 14.6 to 19.4). The median duration of active treatment was 1.8 months for regorafenib and 0.9 months for placebo (Table 2). The median regorafenib dose-intensity was 149 mg per day, with average dose-intensity of 80% at 160 mg per day (128 mg per day) attained by 67% of patients receiving regorafenib and 76% of those receiving placebo. Twenty-nine patients (58%) receiving placebo chose regorafenib treatment after progression (post-progression treatments by region are listed in Appendix Table A1, online only).

Table 2.

Treatment Duration (time to discontinuation) in Treatment Groups

| Duration Percentile | Median (95% CI) Duration (months) | |

|---|---|---|

| Regorafenib (n = 97) | Placebo (n = 50) | |

| 25th | 0.9 (0.9 to 1.0) | 0.9 (0.7 to 0.9) |

| 50th | 1.8 (1.4 to 2.0) | 0.9 (0.9 to 1.0) |

| 75th | 3.2 (2.7 to 4.4) | 1.6 (1.0 to 1.8) |

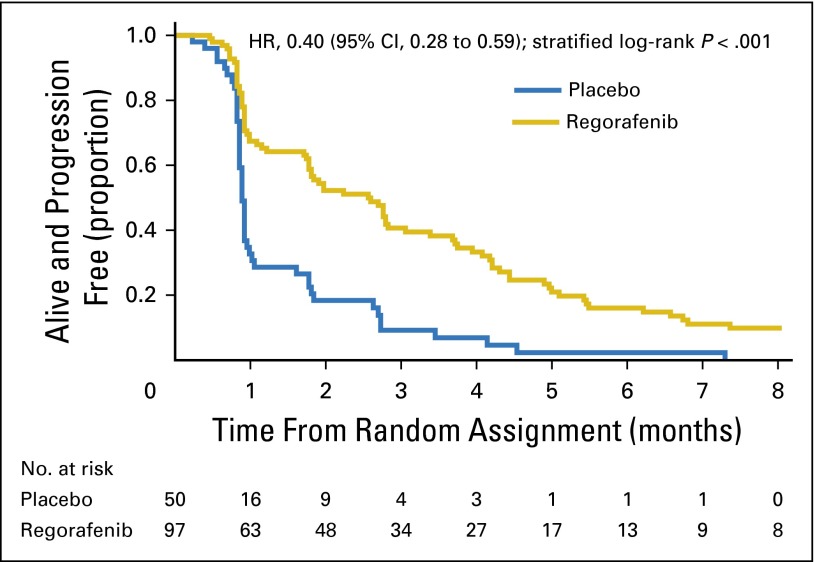

Eighty-six patients receiving regorafenib and 48 receiving placebo experienced disease progression or died. The proportion alive and progression free at 2 months was 0.52 (95% CI, 0.42 to 0.62) for regorafenib and 0.18 (95% CI, 0.09 to 0.3) for placebo. The median PFS was 2.6 months (95% CI, 1.8 to 3.1) for those receiving regorafenib and 0.9 months (95% CI, 0.9 to 0.9) for those receiving placebo (Fig 2). The estimated HR was 0.40 (95% CI, 0.28 to 0.59; stratified log-rank P < .001); it was virtually identical when calculated for all randomly assigned patients (HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.27 to 0.57; stratified log-rank P < .001).

Fig 2.

Kaplan-Meier plot of progression-free survival after random assignment. HR, hazard ratio.

Three patients receiving regorafenib (95% CI, 1% to 9%) and one receiving placebo (95% CI, 0% to 11%) experienced an objective complete or partial response. Three receiving regorafenib commenced nonprotocol anticancer therapy without prior evidence of progression before week 10. Of the remaining 94 patients receiving regorafenib, 44 (95% CI, 36% to 57%) experienced clinical benefit at 2 months, compared with nine (95% CI, 9% to 31%) receiving placebo.

Seventy-eight patients receiving regorafenib and 43 receiving placebo died. Median OS was 5.8 months (95% CI, 4.4 to 6.8) in the regorafenib group and 4.5 months (95% CI, 3.4 to 5.2) in the placebo group (Fig 3). The estimated HR was 0.74 (95% CI, 0.51 to 1.08; stratified log-rank P = .147); it was similar when calculated for all randomly assigned patients (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.49 to 1.02; stratified log-rank P = .06).

Fig 3.

Kaplan-Meier plot of overall survival after random assignment. HR, hazard ratio.

Covariates tested as prognostic factors for PFS are summarized in (Appendix Table A2, online only). Higher baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio was an independent prognostic factor for OS (HR, 1.82; P = .001). Independent prognostic factors for PFS were age older than 60 years (HR, 0.68; P = .04) and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (HR, 1.56; P = .01). More than two lines of therapy and number of metastatic sites were also prognostic factors for PFS in univariable analyses. After adjustment for significant prognostic factors, the treatment effect on PFS remained highly statistically significant (HR, 0.39; P < .001), and there was a trend toward improved survival (HR, 0.70; P = .06).

QLQ-C30 Global Health Subscale mean estimates for regorafenib versus placebo were 53 (95% CI, 48 to 58) versus 58 (95% CI, 51 to 65) at week 4 and 54 (95% CI, 48 to 60) versus 56 (95% CI, 45 to 67) at week 8, respectively. A detailed QoL analysis will be published separately.

There were two grade 5 serious AEs in the regorafenib group, one reported as hepatic failure (but with obstructive picture on liver enzymes attributed to disease progression) and one death with unresolved grade 3 abdominal pain. There was one grade 5 serious AE in the placebo group (unspecified death), and one patient died with unresolved grade 4 anorexia. All other deaths were attributed to disease progression. Thirty-two percent of patients receiving regorafenib and 18% of those receiving placebo experienced at least one serious AE. The most common grade 3 to 5 serious AE classes with regorafenib were GI disorders (11% v 0% in placebo group), infections (6% v 2% in placebo group), and metabolism and nutrition disorders (4% v 2% in placebo group). The most common grade 3 to 5 AEs in the regorafenib arm are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Grade 3 to 5 AEs With More Than 5% Incidence in Regorafenib Arm

| Type of AE* | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Regorafenib (n = 97) | Placebo (n = 50) | |

| Anorexia | 6 (6) | 3 (6) |

| AST level increased | 9 (9) | 0 (0) |

| Abdominal pain | 5 (5) | 1 (2) |

| Hypertension | 10 (10) | 1 (2) |

| γ-glutamyltransferase level increased | 6 (6) | 4 (8) |

| ALT level increased | 8 (8) | 3 (6) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders, other† | 6 (6) | 0 (0) |

| Pain | 5 (5) | 2 (4) |

| Hypophosphatemia | 5 (5) | 0 (0) |

| At least one grade 3 to 5 AE | 65 (67) | 26 (52) |

NOTE. If a patient had more than one event of the same type, that with the worst grade was used to populate each row of the table.

Abbreviation: AE, adverse event.

From National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4.0).

When all AE terms falling within the skin and subcutaneous tissue disorder class (except for alopecia) were combined, there were nine (9%) grade 3 events for regorafenib and two (4%) for placebo. For palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome alone, there were two (2%) grade 3 events for regorafenib and one (2%) for placebo.

Test of interaction between treatment assignment and (preplanned) subgroup characteristics regarding PFS is shown in Fig 4. There was no statistical evidence that any of the following factors modified the effectiveness of treatment on PFS: age, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, primary site, lines of therapy, presence of peritoneal metastases, number of sites of metastatic disease, and baseline plasma VEGF-A. There was strong statistical evidence that the treatment effect was greater in South Korea than Australia, New Zealand, or Canada (region-by-treatment interaction P < .001). There were significant differences among regions in distribution of VEGF-A, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, primary site, and previous lines of therapy (Appendix Table A3, online only). The observed region-by-treatment interaction did not change after adjustment for all prespecified subgroup covariates and associated interaction terms.

Fig 4.

Forest plot of progression-free survival hazard ratios (HRs) by subgroup. NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor. (*) P for interaction between treatment and subgroups.

DISCUSSION

This phase II trial was designed to identify activity of regorafenib in refractory GC relative to a prespecified reference benchmark (a median PFS of 2 months), and the placebo arm was a calibration group to assess the applicability of this reference. This design was advantageous because the results for placebo showed the reference benchmark to be overly optimistic, giving direct comparisons between groups more weight. The activity of regorafenib was demonstrated by the significantly lower rate of progression or death among patients receiving regorafenib compared with placebo.

After the design and initiation of INTEGRATE, ramucirumab, an anti–VEGF-R2 monoclonal antibody, was demonstrated to improve survival in the second-line setting in two phase III trials. Compared with placebo, ramucirumab improved OS, both as a single agent (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.60 to 1.00; P = .047)22 and in combination with paclitaxel (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.68 to 0.96; P = .02).23 A Chinese placebo-controlled phase III trial of apatinib (an oral VEGF-R2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor) also reported prolonged survival in refractory gastric adenocarcinoma.24 In our study, the absolute difference in median PFS between the regorafenib and placebo groups was similar to that of the other agents in this setting: apatinib (median PFS, 2.6 v 1.3 months for placebo; HR, 0.44; P < .001)24 and ramucirumab (median PFS, 2.1 v 1.3 months for placebo; HR, 0.48; P < .001).22

INTEGRATE was not designed to detect PFS, survival, or QoL differences. However, a trend toward improved OS was seen in the regorafenib arm, even though 58% of the placebo arm received regorafenib after disease progression. Neither the PFS benefit nor the survival trend was accompanied by evidence of a decrement in QoL, but available QoL information was limited by the size of INTEGRATE.

The frequency and severity of AEs were no worse than in other studies of regorafenib. There were fewer grade 3 and 4 hand-foot skin reactions and fatigue than in the CORRECT (Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer) study in refractory metastatic colorectal cancer.19 Regorafenib may have been better tolerated in INTEGRATE because of drug absorption or racial differences in drug pharmacokinetics (PKs) or because of better management of toxicities by investigators experienced in its use. Analysis of regorafenib PKs by region would be of interest.

Analyses evaluating prespecified patient characteristics as prognostic factors found that younger age and higher neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio were both independently associated with poor PFS, possibly because younger patients may have more aggressive forms of gastric cancer, whereas older patients may have more comorbidities, counterbalancing effects on survival.25 The importance of baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic factor in adenocarcinoma is now recognized.26 The treatment effects of regorafenib were similar, irrespective of the levels of these prognostic factors. Additional biomarker analyses are ongoing.

The greater PFS benefit of regorafenib in the South Korean cohort was not explained by other factors in a multivariable analysis and contradicts the observation of a lesser OS benefit seen with bevacizumab in Asians in AVAGAST.10 Possible explanations include differences in genetic polymorphisms predicting differential drug response, differentially distributed molecular phenotypes conferring differing prognoses and drug sensitivity27 (differential expression of angiogenesis-related genes has been documented in GC with and without high-frequency microsatellite instability28), PK differences by population, or a combination thereof.

No participant in INTEGRATE had received any prior anti-VEGF treatment. Modern practice today would likely include second-line chemotherapy with ramucirumab in fit patients, thus leaving the refractory setting as an ongoing area of clinical need. Although a phase III trial of apatinib in refractory GC has been completed, data are limited to Chinese patients. Future trials in refractory GC will need to consider prior use of ramucirumab in study designs.

This is the first study to our knowledge to demonstrate activity of regorafenib in GC after failure of prior chemotherapy. A multinational phase III trial in refractory GC (INTEGRATE II) is commencing in 2016, and studies evaluating regorafenib with chemotherapy in earlier settings are under way.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This study was conducted by the Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group in collaboration with the National Health and Medical Research Council Clinical Trials Centre, University of Sydney. In Canada, the study was conducted through the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group, and in South Korea, it was conducted by INC Research, independently of the funders. Rhana Pike, from the Clinical Trials Centre, assisted with the manuscript. We thank the patients and investigators for their participation in this study.

Appendix

Trial ParticipantsTrial management committee: Nick Pavlakis (co-chair), David Goldstein (co-chair), Katrin Sjoquist (clinical lead), Matthew Burge, Michelle Cronk, Dean Harris, Lara Lipton, Andrew Martin, Louise Nott, Tim Price, Jenny Shannon, Andrew Strickland, Niall Tebbutt, Eric Tsobanis, Nicole Wong, and Sonia Yip.

International trial management group: Nick Pavlakis, David Goldstein, Katrin Sjoquist, Eric Tsobanis, John Simes, John Zalcberg, Yung-Jue Bang, Yoon-Koo Kang, Margot Burnell, Thierry Alcindor, and Chris O’Callaghan.

Clinical Trials Centre: Katrin Sjoquist, Eric Tsobanis, Andrew Martin, John Simes, Sonya Yip, Rhana Pike, Wendy Hague, Mark Donoghoe, Emma Gibbs, Brad Green, Kristy Mann, Karen Miranda, and Emily Tu.

Data and safety monitoring committee: Alan Coates (chair), Howard Gurney, Viet Do, and Ian Marschner.

Adjudication committee: John Simes, Wendy Hague, Katrin Sjoquist, Nick Pavlakis, David Goldstein, Andrew Martin, and Eric Tsobanis.

Participating centers: Australia and New Zealand: Austin Hospital, Niall Tebbutt; Ballarat Oncology and Haematology Services, George Kannourakis; Barwon Health (Geelong Hospital), Mustafa Khasraw; Border Medical Oncology, Craig Underhill; Cabrini Hospital, Jeremy Shapiro; Calvary Mater Newcastle, Newcastle Private Hospital, Tony Bonaventura; Canberra Hospital, Yu Jo Chua; Christchurch Hospital, Dean Harris; Flinders Medical Centre, Chris Karapetis; Icon Cancer Foundation, Vikram Jain; Monash Medical Centre, Andrew Strickland; Nambour General Hospital, Michelle Cronk; Nepean Cancer Care Centre, Jenny Shannon; Palmerston North Hospital, Richard Issacs and Helen Winter; Peninsula Health (Frankston Hospital), Nicole Potasz; Port Macquarie/North Coast Cancer Institute, Stephen Begbie; Prince of Wales Hospital, David Goldstein; Royal Adelaide Hospital, Nimit Singhal; Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Matthew Burge; Royal Hobart Hospital, Louise Nott; Royal North Shore Hospital, Nick Pavlakis; St George Hospital, Katrin Sjoquist; St John of God Subiaco, David Ransom and Tom van Hagen; St Vincent’s Public Hospital, Richard Epstein; Alfred Hospital, Sanjeev Gill; Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Tim Price; Townsville Hospital, Suresh Varma; Western Hospital, Lara Lipton; and Westmead Hospital, Mark Wong.

Canada: Allan Blair Cancer Centre, Haj Chalchal; Atlantic Health Sciences Corporation, Margot Burnell; British Columbia Cancer Agency (BCCA) Fraser Valley, Thuan Do; BCCA Vancouver Cancer Centre, Howard Lim; CancerCare Manitoba, Ralph Wong; Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke, Fredric Lemay; Hôspital Notre-Dame, Francine Aubin; London Regional Cancer Program, Mary Mackenzie; McGill University Health Centre, Thierry Alcindor; Mount Sinai Hospital, Ron Burkes; Odette Cancer Centre, Sunnybrook Hospital, Scott Berry; Ottawa Health Research Institute, Rachel Goodwin; Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre, Stephanie Snow and Wojciech Morzycki; Saskatoon Cancer Centre, Shahid Ahmed; St Michael’s Hospital, Christine Brezden-Masley; Toronto East General Hospital, Richard Shao; and University Health Network, Princess Margaret Hospital, Geoffrey Liu.

South Korea: Asan Medical Centre, Yoon-Koo Kang; Gangnam Severance Hospital Yonsei University, Jae-Yong Cho; Korea University Hospital, Yeul Hong Kim; Samsung Medical Centre, Jeeyun Lee; Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Jin Won Kim; Seoul National University Hospital, Yung-Jue Bang; and Yonsei Cancer Centre, Sun Young Rha.

Study Design

Patients were randomly assigned to either an active arm in which regorafenib was administered in the context of a conventional single-arm Simon’s two-stage trial design or a calibration arm in which placebo treatment was administered. For sample size calculation, a progression-free survival rate of 50% at 2 months was considered plausible, and an increase to 66% with regorafenib was considered of clinical interest. Accrual of 92 patients in the regorafenib group provided 90% power at the 5% level of significance to reject the null hypothesis. This design also allowed for early stopping (in stage one) if 16 or more of the first 33 evaluable participants receiving regorafenib had progressive disease by 2 months. The target sample size for the regorafenib arm was adjusted to 100 to allow for dropout and ineligibility. A sample of at least 50 evaluable patients in the placebo calibration arm was sought to provide contemporaneous progression-free survival data to informally evaluate the applicability of the prespecified reference rate for the target population and to inform the reference values used in any future sample-size calculations for a phase III trial.

Given the design of INTEGRATE, direct comparisons between randomly assigned groups were to be undertaken in an exploratory manner, with the emphasis of the analysis on the quantification of outcomes for patients randomly assigned to regorafenib (including an appraisal of the observed median progression-free survival relative to the reference period of 2 months). The actual progression-free survival observed in the placebo arm, however, indicated that the prespecified null hypothesis (median progression-free survival of 2 months) was overly optimistic and not an appropriate reference against which to assess progression-free survival in the regorafenib arm. Greater emphasis was therefore placed on the results of the direct comparisons between the placebo and regorafenib groups.

Table A1.

Postprogression Treatment by Region

| Nonprotocol Anticancer Therapy | No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia, New Zealand, and Canada | South Korea | |||

| Regorafenib (n = 62) | Placebo (n = 35) | Regorafenib (n = 31) | Placebo (n = 19) | |

| No active treatment administered | 38 (61) | 12 (34) | 22 (71) | 6 (32) |

| Open-label regorafenib | 0 (0) | 16 (46) | 0 (0) | 10 (53) |

| Started regorafenib but did not finish one cycle | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 2 (11) |

| FOLFOX or FOLFIRI | 5 (8) | 3 (9) | 10 (32) | 1 (5) |

| Docetaxel with cisplatin, fluorouracil, or irinotecan | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (11) |

| Docetaxel | 3 (5) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 2 (11) |

| Irinotecan | 9 (15) | 3 (9) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Paclitaxel | 2 (3) | 3 (9) | 5 (16) | 2 (11) |

| Regimen including trastuzumab | 4 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Triple therapy* | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Radiation therapy | 4 (6) | 3 (9) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Others | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (10) | 3 (16) |

Abbreviations: FOLFIRI, fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan; FOLFOX, fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin

Epirubicin, cisplatin, and fluorouracil; epirubicin, carboplatin, and fluorouracil; or epirubicin, cisplatin, and capecitabine.

Table A2.

Prognostic Factors in Efficacy Analysis Set (n = 147)

| Factor | Univariable Analyses | Multivariable Analysis (stepwise selection)* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR for Covariate (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Progression-free survival | ||||

| Region: Australia, New Zealand, or Canada v South Korea | 1.04 (0.72 to 1.49) | .8 | — | |

| Primary site: stomach or other v esophagogastric junction | 0.73 (0.51 to 1.04) | .08 | — | |

| Previous lines of therapy: two v one | 1.46 (1.03 to 2.07) | .04 | — | |

| Peritoneum metastasis: yes v no | 0.91 (0.62 to 1.33) | .64 | — | |

| No. of metastatic sites†‡ | ||||

| ≥ 3 v 0-1 | 1.55 (1 to 2.42) | — | ||

| 2 v 0-1 | 1.39 (0.92 to 2.1) | — | ||

| Age: > 60 v ≤ 60 years | 0.67 (0.47 to 0.96) | .03 | 0.68 (0.48 to 0.97) | .04 |

| Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio: ≥ 3 v < 3 | 1.58 (1.11 to 2.25) | .01 | 1.56 (1.10 to 2.2) | .01 |

| VEGF-A: high v low | 1.35 (0.95 to 1.9) | .09 | — | |

| Treatment: regorafenib v placebo | 0.40 (0.28 to 0.59) | < .001 | 0.39 (0.26 to 0.57) | < .001 |

| Overall survival | ||||

| Region: Australia, New Zealand, or Canada v South Korea | 1.45 (0.99 to 2.13) | .06 | — | |

| Primary site: stomach or other v esophagogastric junction | 0.72 (0.50 to 1.04) | .08 | — | |

| Previous lines of therapy: two v one | 0.95 (0.66 to 1.37) | .8 | — | |

| Peritoneum metastases: yes v no | 1.21 (0.82 to 1.77) | .3 | — | |

| No. of metastatic sites†§ | ||||

| ≥ 3 v 0-1 | 1.56 (1.0 to 2.44) | .05 | — | |

| 2 v 0-1 | 0.96 (0.62 to 1.49) | .9 | — | |

| Age: > 60 v ≤ 60 years | 0.81 (0.56 to 1.16) | .2 | — | |

| Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio: ≥ 3 v < 3 | 1.82 (1.27 to 2.63) | .001 | 1.82 (1.27 to 2.63) | .001 |

| VEGF-A: high v low (around median) | 1.46 (1.01 to 2.11) | .04 | — | |

| Treatment: regorafenib v placebo | 0.74 (0.51 to 1.08) | .1 | 0.70 (0.48 to 1.01) | .06 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Final models shown fitted to all available data following stepwise selection strategy.

Fitted as ordinal variable with three levels in model selection process.

Trend P = .05 in univariable analysis.

Trend P = .03 in univariable analysis.

Table A3.

Baseline Patient Clinical Characteristics by Region

| Characteristic | South Korea (n = 54) | Australia, New Zealand, and Canada (n = 93) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma VEGF-A, pg/mL* | .002† | ||

| Mean (SD) | 40.4 (114) | 81.2 (139.8) | |

| Range | 0.1-543.8 | 0.1-660.6 | |

| Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio | < .001† | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.1 (2.3) | 5.4 (4.6) | |

| Range | 0.6-14.3 | 1-27 | |

| Age, years | .09† | ||

| Mean (SD) | 58.4 (10.7) | 61.5 (11.7) | |

| Range | 33.8-75.1 | 32.1-84.8 | |

| Primary site, No. (%) | < .001‡ | ||

| Esophagogastric junction | 2 (4) | 54 (58) | |

| Stomach or other | 52 (96) | 39 (42) | |

| Lines of therapy for recurrent or metastatic disease, No. (%) | < .001‡ | ||

| 1 | 9 (17) | 53 (57) | |

| 2 | 45 (83) | 40 (43) | |

| Peritoneum metastasis, No. (%) | .17‡ | ||

| No | 33 (61) | 67 (72) | |

| Yes | 21 (39) | 26 (28) | |

| No. of sites with metastatic disease, No. (%) | .19‡ | ||

| 0-1 | 12 (22) | 33 (36) | |

| 2 | 26 (48) | 33 (36) | |

| 3+ | 16 (30) | 27 (29) |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Values below the limit of quantification were assigned the minimum quantitative value recorded (ie, 0.14).

Wilcoxon test.

χ2 test.

Footnotes

Supported by an unrestricted research grant from Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals to the Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group to conduct the study independently and by National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Program Grant No. 1037786 to the NHMRC Clinical Trials Centre.

Presented at the 51st Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Chicago, IL, May 29-June 2, 2015, and the 17th European Society for Medical Oncology World Congress on Gastrointestinal Cancer, Barcelona, Spain, July 1-4, 2015.

Authors’ disclosures of potential conflicts of interest are found in the article online at www.jco.org. Author contributions are found at the end of this article.

Clinical trial information: ANZCTR 12612000239864.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Nick Pavlakis, Katrin M. Sjoquist, Andrew J. Martin, Eric Tsobanis, Sonia Yip, Niall C. Tebbutt, John R. Zalcberg, John Simes, David Goldstein

Provision of study materials or patients: Nick Pavlakis, Katrin M. Sjoquist, Eric Tsobanis, Sonia Yip, Yoon-Koo Kang, Yung-Jue Bang, Thierry Alcindor, Christopher J. O'Callaghan, Margot J. Burnell, Niall C. Tebbutt, Sun Young Rha, Jeeyun Lee, Jae-Yong Cho, Lara R. Lipton, Mark Wong, Andrew Strickland, Jin Won Kim, David Goldstein

Collection and assembly of data: Nick Pavlakis, Katrin M. Sjoquist, Eric Tsobanis, Sonia Yip, Yoon-Koo Kang, Yung-Jue Bang, Thierry Alcindor, Christopher J. O’Callaghan, Niall C. Tebbutt, Sun Young Rha, Jeeyun Lee, Jae-Yong Cho, Lara R. Lipton, Mark Wong, Andrew Strickland, Jin Won Kim, David Goldstein

Data analysis and interpretation: Nick Pavlakis, Katrin M. Sjoquist, Andrew J. Martin, Eric Tsobanis, Sonia Yip, Yoon-Koo Kang, Yung-Jue Bang, Thierry Alcindor, Christopher J. O’Callaghan, Margot J. Burnell, Niall C. Tebbutt, Andrew Strickland, John R. Zalcberg, John Simes, David Goldstein

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Regorafenib for the Treatment of Advanced Gastric Cancer (INTEGRATE): A Multinational Placebo-Controlled Phase II Trial

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO’s conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jco.ascopubs.org/site/ifc.

Nick Pavlakis

Honoraria: AstraZeneca, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche Pharma AG, Merck Serono, Ipsen

Consulting or Advisory Role: Merck Serono, Amgen, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Novartis, Roche Pharma AG, Ipsen, Merck, Baxalta, Specialised Therapeutics, AstraZeneca

Katrin M. Sjoquist

Honoraria: Pfizer

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Merck Serono, Ipsen

Andrew J. Martin

No relationship to disclose

Eric Tsobanis

No relationship to disclose

Sonia Yip

No relationship to disclose

Yoon-Koo Kang

Consulting or Advisory Role: Eli Lilly/ImClone, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, Genentech, Novartis

Research Funding: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Genentech

Yung-Jue Bang

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals

Research Funding: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals

Thierry Alcindor

Consulting or Advisory Role: Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline/Novartis, Amgen

Christopher J. O'Callaghan

No relationship to disclose

Margot J. Burnell

No relationship to disclose

Niall C. Tebbutt

Honoraria: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals

Sun Young Rha

No relationship to disclose

Jeeyun Lee

No relationship to disclose

Jae-Yong Cho

No relationship to disclose

Lara R. Lipton

No relationship to disclose

Mark Wong

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Sirtex Medical, Roche, Ipsen

Andrew Strickland

No relationship to disclose

Jin Won Kim

No relationship to disclose

John R. Zalcberg

Honoraria: Amgen, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Merck Serono

Consulting or Advisory Role: Amgen, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Merck Serono

Research Funding: Novartis, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Amgen, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Merck Serono, Roche Pharma AG, AstraZeneca

John Simes

Research Funding: Bayer Schering Pharma (Inst)

David Goldstein

Stock or Other Ownership: Sirtex Medical

Research Funding: Amgen (Inst), Celgene (Inst), Pfizer (Inst)

REFERENCES

- 1.Brenner H, Rothenbacher D, Arndt V. Epidemiology of stomach cancer. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;472:467–477. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-492-0_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wagner AD, Unverzagt S, Grothe W, et al. Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(3):CD004064. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004064.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kang JH, Lee SI, Lim H, et al. Salvage chemotherapy for pretreated gastric cancer: A randomized phase III trial comparing chemotherapy plus best supportive care with best supportive care alone. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1513–1518. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.4585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ford HER, Marshall A, Bridgewater JA, et al. Docetaxel versus active symptom control for refractory oesophagogastric adenocarcinoma (COUGAR-02): An open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:78–86. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70549-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thuss-Patience PC, Kretzschmar A, Bichev D, et al. Survival advantage for irinotecan versus best supportive care as second-line chemotherapy in gastric cancer: A randomised phase III study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie (AIO) Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2306–2314. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ku GY, Ilson DH. Esophagogastric cancer: Targeted agents. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36:235–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor: Basic science and clinical progress. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:581–611. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fondevila C, Metges JP, Fuster J, et al. p53 and VEGF expression are independent predictors of tumour recurrence and survival following curative resection of gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:206–215. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yao JC, Wang L, Wei D, et al. Association between expression of transcription factor Sp1 and increased vascular endothelial growth factor expression, advanced stage, and poor survival in patients with resected gastric cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4109–4117. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohtsu A, Shah MA, Van Cutsem E, et al. Bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy as first-line therapy in advanced gastric cancer: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3968–3976. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bang YJ, Kang YK, Kang WK, et al. Phase II study of sunitinib as second-line treatment for advanced gastric cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2011;29:1449–1458. doi: 10.1007/s10637-010-9438-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doi T, Muro K, Boku N, et al. Multicenter phase II study of everolimus in patients with previously treated metastatic gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1904–1910. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.2923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wehland M, Bauer J, Magnusson NE, et al. Biomarkers for anti-angiogenic therapy in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:9338–9364. doi: 10.3390/ijms14059338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Cutsem E, de Haas S, Kang Y-K, et al. Bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy as first-line therapy in advanced gastric cancer: A biomarker evaluation from the AVAGAST randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2119–2127. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.9824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demetri GD, Reichardt P, Kang Y-K, et al. Efficacy and safety of regorafenib for advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours after failure of imatinib and sunitinib (GRID): An international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381:295–302. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61857-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grothey A, Van Cutsem E, Sobrero A, et al. Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): An international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381:303–312. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61900-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blazeby JM, Conroy T, Bottomley A, et al. Clinical and psychometric validation of a questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-STO 22, to assess quality of life in patients with gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:2260–2268. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.EuroQol Group EuroQol: A new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stockler MR, O’Connell R, Nowak AK, et al. Effect of sertraline on symptoms and survival in patients with advanced cancer, but without major depression: A placebo-controlled double-blind randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:603–612. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis ID, Long A, Yip S, et al. EVERSUN: A phase 2 trial of alternating sunitinib and everolimus as first-line therapy for advanced renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1118–1123. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuchs CS, Tomasek J, Yong CJ, et al. Ramucirumab monotherapy for previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (REGARD): An international, randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;383:31–39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61719-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilke H, Muro K, Van Cutsem E, et al. Ramucirumab plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel in patients with previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (RAINBOW): A double-blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1224–1235. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70420-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qin S. Phase III study of apatinib in advanced gastric cancer: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial; J Clin Oncol; 2014. p. 5s. suppl; abstr 4003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim KH, Kim YM, Kim MC, et al. Analysis of prognostic factors and outcomes of gastric cancer in younger patients: A case control study using propensity score methods. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:3369–3375. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i12.3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang X, Zhang W, Feng LJ. Prognostic significance of neutrophil lymphocyte ratio in patients with gastric cancer: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e111906. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network: Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature 513:202-209.28, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Miyamoto N, Yamanoto H, Taniguchi H, et al. Differential expression of angiogenesis-related genes in human gastric cancers with and those without high-frequency microsatellite instability. Cancer Lett. 2007;254:42–53. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.