Abstract

Purpose

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a leading cause of death among women with nonmetastatic breast cancer. Whether exercise is associated with reductions in CVD risk in patients with breast cancer with an elevated CVD risk phenotype is not known.

Methods

Using a prospective design, women (n = 2,973; mean age, 57 years) diagnosed with nonmetastatic breast cancer participating in two registry-based, regional cohort studies, completed a questionnaire that assessed leisure-time recreational physical activity (metabolic equivalent task [MET]-h/wk). The primary end point was the first occurrence of any of the following: new diagnosis of coronary artery disease, heart failure, valve abnormality, arrhythmia, stroke, or CVD death, occurring after study enrollment.

Results

Median follow-up was 8.6 years (range, 0.2 to 14.8 years). In multivariable analysis, the incidence of cardiovascular events decreased across increasing total MET-h/wk categories (Ptrend < .001). Compared with < 2 MET-h/wk, the adjusted hazard ratio was 0.91 (95% CI, 0.76 to 1.09) for 2 to 10.9 MET-h/wk, 0.79 (95% CI, 0.66 to 0.96) for 11 to 24.5 MET-h/wk, and 0.65 (95% CI, 0.53 to 0.80) for ≥ 24.5 MET-h/wk. Similar trends were observed for the incidence of coronary artery disease and heart failure (P values < .05). Adherence to national exercise guidelines for adult patients with cancer (ie, ≥ 9 MET-h/wk) was associated with an adjusted 23% reduction in the risk of cardiovascular events in comparison with not meeting the guidelines (< 9 MET-h/wk; P < .001). The association with exercise did not differ according to age, CVD risk factors, menopausal status, or anticancer treatment.

Conclusion

Exercise is associated with substantial, graded reductions in the incidence of cardiovascular events in women with nonmetastatic breast cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Improvements in screening and adjuvant therapy have led to significant reductions in cancer-specific mortality in women with nonmetastatic breast cancer.1 With continual improvements in cancer outcomes, these patients are becoming increasingly susceptible to noncancer competing causes of mortality, particularly cardiovascular disease (CVD).

CVD is now the leading cause of death among women with nonmetastatic breast cancer, especially for those older than 65 years of age2-5 and with preexisting CVD risk factors (eg, hypertension, obesity, history of cardiovascular disease) at diagnosis. Moreover, patients with nonmetastatic breast cancer may be at increased risk of CVD compared with age-matched women without a history of breast cancer because of the direct toxic effects of anticancer therapy (eg, cardiomyocyte death, endothelial dysfunction) as well as effects secondary to therapy (eg, deconditioning).6 The magnitude of this problem may increase with continual improvements in cancer-specific outcomes and approval of newer antineoplastic agents that are administered for a longer duration than their predecessors,7 together with the increase in breast cancer incidence due to the rapidly aging population.8 In totality, breast cancer therapy–associated CVD is in danger of attenuating further improvements in overall survival among women with nonmetastatic breast cancer.9

Given the growing clinical importance, effective preventive and/or treatment strategies to offset chronic and long-term CVD in women after a breast cancer diagnosis are urgently required. A wealth of evidence demonstrates that exercise consistent with the national guidelines (ie, three to five sessions of moderate- or vigorous-intensity exercise per week for ≥ 20 minutes) is associated with a strong, graded reduction in CVD mortality in multiple clinical settings.10 Accordingly, exercise is considered the first-line treatment for patients with myocardial infarction, chronic stable angina, and heart failure and after coronary artery bypass surgery or percutaneous coronary intervention.11 Whether exercise confers similar cardiovascular (CV) -specific benefits in women with breast cancer with an elevated CVD risk phenotype due to cytotoxic therapy is not known. Accordingly, we investigated the association between exercise exposure and CVD events in women with nonmetastatic breast cancer. Specifically, we investigated whether exercise was an independent predictor of CVD events, whether a dose relationship exists, and whether the association between exercise and CVD end points differed based on baseline cardiovascular risk profile and type of anticancer therapy.

METHODS

Patients and Study Overview

Women with nonmetastatic breast cancer (American Joint Committee on Cancer stage I with tumor size ≥ 1 cm, stage II, or stage IIIA) were selected from two registry-based, regional cohort studies: the Life After Cancer Epidemiology (LACE) study12 and Pathways.13 In brief, major eligibility for LACE was primary diagnosis of invasive breast cancer from 1996 to 2000, 18 to 79 years old at diagnosis, completion of primary adjuvant therapy, and no evidence of recurrence or metastatic disease at study entry. Major eligibility for Pathways included primary diagnosis of stage I to III breast cancer from 2005 to 2008 and 21 years or older at diagnosis. Major exclusion criteria for both studies were invasive tumor < 0.5 cm diameter, bilateral disease, and neoadjuvant therapy. LACE and Pathways protocols were reviewed and approved by the human subjects committees at Kaiser Permanente Northern California and University of Utah, and informed consent was obtained before study participation. The total study population consisted of 4,307 women enrolled in LACE and Pathways; of these, exercise exposure data were available on 3,975. CVD end points could not be ascertained in 225 LACE participants; 137 participants were excluded for other eligibility reasons (stage IV and older than 80 years). In addition, to minimize impact of preexisting CVD in the present analysis (those with existing disease are likely to have reduced exercise behavior due to comorbid conditions), 640 participants with overt CVD at study enrollment (eg, history of heart failure, arrhythmia, stroke) were excluded from this analysis, thus leaving a final analytic cohort of 2,973.

Primary and Secondary Cardiovascular End Points

The primary end point was the first occurrence of any of the following newly diagnosed cardiovascular (CV) events: coronary artery disease (CAD; nonfatal myocardial infarction or death from coronary causes), heart failure, valve abnormality, arrhythmia, stroke, or CVD death, occurring after study enrollment. Secondary end points were incidence of individual CV events. Cardiovascular events were continually updated in real time in the Electronic Medical Record for all members of the health plan. All new events were ascertained from time of diagnosis to July 2015 using standardized International Classification of Diseases, 10th version (ICD-10), 9th revision (ICD-9), and 4th revision (ICD-4) codes for CV conditions as well as death from CVD. The specific ICD codes are provided in supplemental materials (Data Supplement). Cause of death was determined from death certificates and supplemented with medical records.

Exercise Exposure Assessment

Exercise exposure was assessed at study enrollment using items from the Arizona Activity Frequency Questionnaire14 that evaluated different domains of physical activity, including leisure-time recreational activity (ie, exercise). Nonrecreational activity (eg, occupational activity, activities of daily living) was not included in the calculation of exercise exposure. The validity and reliability of this instrument has been previously described.14 In brief, patients reported the frequency and duration of activities (eg, walking, jogging, running, bicycling, swimming laps, racket sports) performed at least once a month in the past 6 (Pathways) or 12 months (LACE). Standardized metabolic equivalent task (MET)15 values were assigned to each activity, with dose being calculated by multiplying the frequency of activity sessions per week by average session duration, weighted by the standardized MET value for the particular exercise modality. Individual activities were summed to derive a total MET-hours per week (MET-h/wk) categorized using a quartile split (≤ 2, 2.1 to 10.3, 10.4 to 24.5, and > 24.6 MET-h/wk). We also calculated the proportion of participants meeting the national guidelines for regular exercise for adult cancer survivors (ie, three to five sessions of moderate- or vigorous-intensity exercise per week of ≥ 20 minutes in duration), the equivalent of ≥ 9 MET-h/wk.16

Statistical Analysis

Demographic, disease, and treatment characteristics are reported by quartiles of exercise exposure and compared using χ2 tests for categorical outcomes and analysis of variance for continuous variables. Both cohorts were followed from study enrollment date through July 2015 until time of primary or secondary end point or censoring at end of enrollment in Kaiser Permanente Northern California. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for the association between exercise exposure categories or meeting national guidelines and incidence of CVD end points after study enrollment/exercise exposure assessment, adjusted for covariates. Covariates were ascertained from study enrollment questionnaires, medical chart review, and tumor registry abstraction and were as follows: age, race, menopausal status, smoking status, body mass index (BMI), tumor stage, study cohort, adjuvant therapy (chemotherapy, radiation, endocrine, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–directed therapy), and cardiovascular risk factors at diagnosis (hypertension, diabetes, BMI, hyperlipidemia, and peripheral vascular disease). Time since diagnosis was the time scale used in the regression models, allowing for delayed entry into the cohort (with study entry ranging from 0 to 3 years postdiagnosis). We also assessed the association between meeting national guidelines and incidence of CVD events according to cardiovascular risk profile at baseline (ie, hypertension, diabetes, BMI, hyperlipidemia, and peripheral vascular disease), menopausal status, and anticancer therapy (ie, treatment with chemotherapy [doxorubicin v non–doxorubicin-containing regimens), radiation, or endocrine therapy [aromatase inhibitors or not]). Adjusted survival curve estimates by exercise (ie, < 9 MET-h/wk v ≥ 9 MET-h/wk) were calculated using the method of Breslow.17 We also conducted sensitivity analyses that excluded all participants experiencing a CVD event within a year of study enrollment. Results from primary and sensitivity analyses were similar; as such, only data from the primary analysis are presented. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R Version 2.14.2 and Stata Version 10.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). A significance probability < .05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical inferences were two sided.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. Patients reporting more exercise, as expected, were younger, white, normal weight, nonsmokers, and had a lower prevalence of preexisting CV conditions at diagnosis. Median follow-up was 8.6 years. During this period, a total of 203 newly diagnosed cases of CAD, 307 cases of heart failure, and 862 overall CVD events were observed. The median overall time from baseline assessment of exercise exposure to first incidence of newly diagnosed CVD event was 5.5 years.

Table 1.

Demographic and Treatment Characteristics of the Participants

| Characteristic | MET-h/wk | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | ≤ 2 | 2.1-10.3 | 10.4-24.5 | > 24.6 | ||

| No. of participants (%) | 2,973 (100) | 741 (24.9) | 747 (25.1) | 741 (24.9) | 744 (25.0) | |

| Age at diagnosis, mean (SD), years | 58.0 (10.5) | 58.7 (10.4) | 56.6 (10.5) | 57.2 (10.3) | 55.4 (10.5) | < .001 |

| Time from diagnosis to enrollment, mean (SD), months | ||||||

| LACE (n = 1,332, 44.8%) | 21.8 (6.5) | 22.7 (6.7) | 21.2 (6.3) | 21.6 (6.3) | 21.9 (6.9) | .19 |

| Pathways (n = 1,641, 55.2%) | 1.9 (0.7) | 1.9 (0.6) | 1.8 (0.7) | 2.0 (0.8) | 1.9 (0.6) | .21 |

| Race, % | .001 | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 72.3 | 68.8 | 69.5 | 74.5 | 76.5 | |

| Other group | 27.7 | 31.2 | 30.5 | 25.5 | 23.5 | |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 27.5 (6.2) | 29.6 (7.3) | 27.8 (6.1) | 26.8 (5.5) | 25.9 (5.1) | < .001 |

| Smoking, % | < .001 | |||||

| Never | 52.7 | 49.8 | 54.3 | 52.0 | 54.6 | |

| Former | 40.8 | 39.3 | 39.1 | 43.1 | 41.9 | |

| Current | 6.5 | 10.9 | 6.6 | 4.9 | 3.5 | |

| Menopausal status, % | < .001 | |||||

| Postmenopausal | 63.5 | 69.4 | 63.7 | 63.3 | 57.7 | |

| Premenopausal | 30.0 | 24.3 | 29.1 | 30.2 | 36.4 | |

| Undetermined | 6.5 | 6.3 | 7.2 | 6.5 | 5.9 | |

| AJCC stage, % | .70 | |||||

| I | 49.8 | 48.9 | 50.2 | 47.8 | 52.3 | |

| II | 42.9 | 43.6 | 42.6 | 44.1 | 41.1 | |

| III | 7.4 | 7.6 | 7.2 | 8.1 | 6.6 | |

| Tumor size, cm, % | .59 | |||||

| < 2 | 57.0 | 54.9 | 57.5 | 58.3 | 57.1 | |

| ≥ 2 | 43.0 | 45.1 | 42.5 | 41.7 | 42.9 | |

| Tumor grade, % | .56 | |||||

| Well or moderately differentiated | 68.6 | 70.3 | 66.9 | 68.0 | 69.3 | |

| Poor/undifferentiated | 31.4 | 29.7 | 33.1 | 32.0 | 30.7 | |

| ER positive, % | 82.2 | 81.2 | 82.4 | 80.0 | 85.1 | .07 |

| PR positive, % | 66.9 | 66.4 | 67.3 | 65.3 | 68.4 | .63 |

| HER2 positive | 15.5 | 15.1 | 17.6 | 15.0 | 14.2 | .30 |

| Clinical subtype,* % | .08 | |||||

| ER-positive/PR-positive/HER2-negative/low-grade | 50.6 | 52.1 | 47.9 | 51.2 | 51.2 | |

| ER-positive/PR-negative/positive/HER2-positive | 32.5 | 30.3 | 34.8 | 30.3 | 34.6 | |

| ER-negative/PR-negative/HER2-positive | 4.8 | 5.3 | 5.9 | 5.3 | 2.8 | |

| ER-negative/PR-negative/HER2-negative | 12.1 | 12.3 | 11.5 | 13.3 | 11.4 | |

| Treatment characteristics, % | ||||||

| Surgery type | .51 | |||||

| Lumpectomy | 57.5 | 60.4 | 57.0 | 55.0 | 57.7 | |

| Mastectomy | 42.3 | 39.4 | 42.8 | 44.9 | 42.1 | |

| None | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Chemotherapy | 55.9 | 53.6 | 57.7 | 57.9 | 54.4 | .22 |

| Radiotherapy | 52.3 | 54.8 | 53.1 | 51.8 | 49.6 | .23 |

| Tamoxifen or Al | 75.3 | 74.4 | 76.7 | 73.8 | 76.2 | .50 |

| Preexisting cardiovascular conditions, % | ||||||

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.1 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 1.1 | .02 |

| Type II diabetes | 8.6 | 12.7 | 8.7 | 7.6 | 5.6 | < .001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 25.7 | 29.4 | 25.7 | 27.4 | 20.2 | < .001 |

| Hypertension | 39.1 | 47.8 | 37.6 | 40.2 | 30.6 | < .001 |

NOTE. Percentages are weighted due to stratified case-cohort study design.

Abbreviations: AI, aromatase inhibitor; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; BMI, body mass index; ER, estrogen receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; LACE, Life After Breast Cancer Epidemiology study; MET, metabolic equivalent task; PR, progesterone receptor.

Clinical subtypes based on three-marker immunohistochemistry plus grade, adapted from St. Gallen’s Consensus Conference.

Multivariable Analyses

Table 2 presents the age-adjusted and the multivariable-adjusted models for CVD events according to total MET-h/wk quartiles. In age-adjusted analysis, the relative risk of cardiovascular events declined across increasing quartiles of total MET-h/wk (1.00, 0.83, 0.72, and 0.57, respectively; Ptrend < .001). Similar trends were observed for the incidence of CAD and heart failure (Table 2). There remained a strong, graded inverse relationship between total MET-h/wk and incidence of cardiovascular events in adjusted models (Ptrend = .001; Table 2). Compared with ≤ 2 MET-h/wk, the adjusted HR was 0.91 (95% CI, 0.76 to 1.09) for 2.1 to 10.3 MET-h/wk, 0.79 (95% CI, 0.66 to 0.96) for 10.4 to 24.5 MET-h/wk, and 0.65 (95% CI, 0.53 to 0.80) for > 24.6 MET-h/wk. Similar trends were observed for the incidence of CAD and heart failure (Table 2).

Table 2.

Age-Adjusted and Multivariable-Adjusted HRs of Cardiovascular Events According to Quartile of Exercise (MET-h/wk)

| Total (N = 2,973) | ≤ 2 (n = 741) | MET-h/wk | Ptrend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1-10.3 (n = 747) | 10.4-24.5 (n = 741) | ≥ 24.6 (n = 744) | ||||

| Median MET-h/wk | 10.3 | 0.0 | 5.4 | 16.3 | 40.0 | |

| Cardiovascular events* | ||||||

| No. of events | 862 | 262 | 243 | 198 | 159 | |

| Age-adjusted HR (95% CI) | Ref | 0.83 (0.70 to 0.99) | 0.72 (0.60 to 0.86) | 0.57 (0.47 to 0.69) | < .001 | |

| Multivariable-adjusted HR (95% CI)† | Ref | 0.91 (0.76 to 1.09) | 0.79 (0.66 to 0.96) | 0.65 (0.53 to 0.80) | .001 | |

| Coronary artery disease | ||||||

| No. of events | 203 | 68 | 55 | 46 | 34 | |

| Age-adjusted HR (95% CI) | Ref | 0.74 (0.52 to 1.06) | 0.65 (0.45 to 0.95) | 0.51 (0.34 to 0.76) | .01 | |

| Multivariable-adjusted HR (95% CI)† | Ref | 0.89 (0.62 to 1.28) | 0.78 (0.53 to 1.15) | 0.63 (0.41 to 0.97) | .04 | |

| Heart failure | ||||||

| No. of events | 307 | 93 | 97 | 66 | 51 | |

| Age-adjusted HR (95% CI) | Ref | 0.97 (0.73 to 1.28) | 0.67 (0.49 to 0.92) | 0.55 (0.39 to 0.77) | .001 | |

| Multivariable-adjusted HR (95% CI)† | Ref | 1.15 (0.86 to 1.55) | 0.77 (0.56 to 1.07) | 0.70 (0.49 to 1.01) | .02 | |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; MET, metabolic equivalent task.

Cardiovascular events include heart failure, coronary artery disease (nonfatal myocardial infarction), arrhythmia, valve abnormality/replacement, stroke, and cardiovascular death.

Adjusted for age at diagnosis (> 50 v ≤ 50 years), race, smoking status, body mass index (continuously), menopausal status, stage, adjuvant therapy, study, and preexisting diabetes and/or peripheral artery disease and/or hyperlipidemia and hypertension.

Adherence to national exercise guidelines for adult patients with cancer (ie, ≥ 9 MET-h/wk) was associated with a significant 23% reduction in the risk of CVD events, in comparison with not meeting the guidelines (< 9 MET-h/wk; Table 3). The corresponding adjusted risk reductions for CAD and heart failure were 26% and 29%, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable-Adjusted HRs of Cardiovascular Events According to Meeting the National Exercise Guidelines for Patients With Cancer (ie, < 9 v ≥ 9 MET-h/wk)

| MET-h/wk | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| < 9 MET-h/wk (n = 1,392) | ≥ 9 MET-h/wk (n = 1,581) | ||

| Median MET-h/wk | 1.6 | 23.4 | |

| Cardiovascular events* | |||

| No. of events | 476 | 386 | |

| Age-adjusted HR (95% CI) | Ref | 0.71 (0.62 to 0.81) | < .001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted HR (95% CI)† | Ref | 0.77 (0.67 to 0.88) | .002 |

| Coronary artery disease | |||

| No. of events | 118 | 85 | |

| Age-adjusted HR (95% CI) | Ref | 0.65 (0.49 to 0.86) | .003 |

| Multivariable-adjusted HR (95% CI)† | Ref | 0.74 (0.55 to 0.99) | .04 |

| Heart failure | |||

| No. of events | 179 | 128 | |

| Age-adjusted HR (95% CI) | Ref | 0.64 (0.51 to 0.80) | .001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted HR (95% CI)† | Ref | 0.71 (0.56 to 0.90) | .01 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; MET, metabolic equivalent task.

Cardiovascular events include heart failure, coronary artery disease (nonfatal myocardial infarction), arrhythmia, valve abnormality/replacement, stroke, and cardiovascular death.

Adjusted for age at diagnosis (> 50 v ≤ 50 years), race, smoking status, body mass index (continuously), menopausal status, stage, adjuvant therapy, study, and preexisting diabetes and/or peripheral artery disease and/or hyperlipidemia and hypertension.

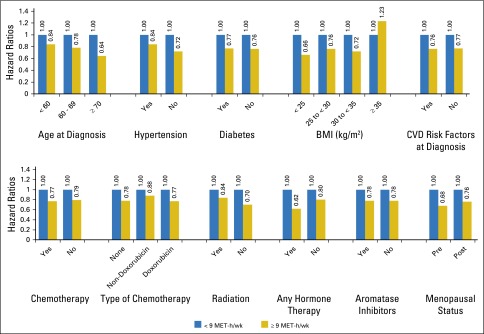

Exercise and CVD Events on the Basis of Baseline CV Risk Profile and Cancer Treatment

In comparison with not meeting the national exercise guidelines (< 9 MET-h/wk), ≥ 9 MET-h/wk was associated with similar significant reductions in the incidence of CVD events irrespective of age, CVD risk factors at diagnosis, menopausal status, and type of anticancer therapy (Fig 1). Regarding chemotherapy regimen, in comparison with < 9 MET-h/wk, the adjusted HR was 0.77 (95% CI, 0.61 to 0.97) for doxorubicin-containing chemotherapy and 0.79 (95% CI, 0.66 to 0.94) for non–doxorubicin-containing chemotherapy for ≥ 9 MET-h/wk. Regarding endocrine therapy, in comparison with < 9 MET-h/wk, the adjusted HR was 0.78 (95% CI, 0.64 to 0.95) for aromatase inhibitors and 0.78 (95% CI, 0.64 to 0.94) for non–aromatase inhibitor therapy for ≥ 9 MET-h/wk. Interaction terms for chemotherapy and endocrine therapy type were not significant (P > .05). Adherence to the guidelines was also associated with significant reductions in CVD events for all BMI categories except with class II obesity (BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2; Fig 1), although no interaction terms were significant.

Fig 1.

Adjusted risk ratios for cardiovascular events according to dichotomized exercise exposure (< 9 metabolic equivalent task [MET]-h/wk v ≥ 9 MET-h/wk) in subgroups defined by age, history of hypertension, body mass index (BMI), and anticancer therapy. Adjusted for the following dichotomized covariates: age (< 50 years, ≥ 50 years), race (white, other), menopausal status (premenopausal, postmenopausal), smoking (never-smoker, other), BMI (mean, 27.5 kg/m2), tumor stage (stage I v other), adjuvant therapy (no treatment v chemotherapy, radiation, endocrine, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–directed therapy), cohort (Pathways, Life After Cancer Epidemiology), and cardiovascular risk factors at diagnosis (no baseline cardiovascular factors v history of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and peripheral vascular disease). All P-interaction tests were nonsignificant. CVD, cardiovascular disease.

DISCUSSION

A growing number of observational studies indicate that postdiagnosis exercise is associated with reductions in all-cause mortality in women with nonmetastatic breast cancer.18,19 In a recent meta-analysis of eight observational studies, postdiagnosis exercise exposure was associated with a significant summary effect size of 0.52 (0.43 to 0.64, 95% CI) for all-cause mortality, although three studies reported a nonsignificant risk reduction.18 All prior work has used broad clinical event classifications, such as death from other causes or total deaths, and has not specifically assessed CVD morbidity. Although a significant proportion of these deaths will be due to CVD, death from breast cancer will also be a significant competing cause of mortality. As such, the impact of exercise on the incidence of CVD-specific morbidity and mortality or the type and nature of CV events had not been investigated.

Here, we found that postdiagnosis exposure to exercise was associated with substantial graded reductions in a composite of newly diagnosed CVD events or CV death in women with early-stage breast cancer. Exercise was associated with a similar graded reduction in the two predominant but distinct forms of CV events in nonmetastatic breast cancer: heart failure (cardiomyopathy) and CAD (atherosclerosis).20,21 Risk of heart failure is important in women with breast cancer because of doxorubicin-containing chemotherapy, the primary contributor to cardiomyopathy.22 The exercise-associated risk reductions in CAD observed here is consistent with the wealth of evidence among women in the general population.23-25 The future risk of heart failure, CAD, and overall CVD in early-stage breast cancer is difficult to predict. From one perspective, risk may decline because of decreasing use of doxorubicin-containing adjuvant therapy (in certain practice regions), newer radiotherapy techniques,26 and minimal risk of cardiomyopathy with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–directed agents without doxorubicin.27 However, from another perspective, risk may continue to increase by more aggressive use of doxorubicin (dose-dense scheduling), approval of taxane-based regimens, approval of aromatase inhibitors, and introduction of targeted agents, all of which have a different CV safety profile than their predecessors.26 Contemporary adjuvant therapy is also generally administered for longer durations, which increases the period of exposure and possibly the extent of CV injury. Irrespective of therapy-induced risk, CVD will remain a leading cause of mortality in early-stage breast cancer given continual improvements in cancer-specific mortality together with the rapidly aging population. Thus, our finding that the cardioprotective effects of exercise are comparable in middle-aged women irrespective of exposure to anticancer therapies is novel and important.

Importantly, the exercise-associated reductions in CVD risk were consistent across patient strata defined by multiple CVD risk factors as well as type of anticancer therapy. The finding that exercise was associated with significant reductions in CV events in patients older than 70 years as well as those with a history of CVD is especially important, because approximately 70% of all cancer diagnoses are expected to occur in adults 65 years or older by the year 2030, and a large proportion of patients will present with CVD risk factors or a history of CVD.8 The finding that exercise is associated with significant reductions in CVD events across all BMI categories up to a BMI < 30 kg/m2 is similar to that observed in the general female population.23,28 The lack of effect in class II obesity (BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2) could be due to several factors (eg, over-reporting of exercise in the morbidly obese or the inability of exercise to counteract the significant excess CVD risk associated with class II obesity). Finally, a question of critical importance not yet investigated is whether the CVD benefits of exercise in women from the general population are also conferred in women with breast cancer who have received known cardiotoxic agents, such as doxorubicin, as well as other agents that may alter CV risk profile, such as aromatase inhibitors.29 Although we did not compare between women with or without breast cancer, we found that the impact of exercise was comparable irrespective of treatment with doxorubicin- or aromatase inhibitor–containing regimens. Collectively, our data indicate that the CVD benefits of exercise are not confined to younger, healthy patients or those not treated with potentially cardiotoxic adjuvant therapy but affect multiple breast cancer subpopulations, including those at high risk of late-occurring CVD.2-5

Collectively, our data, together with prior work, indicate that sedentary survivors of breast cancer, when appropriate, be advised to participate in regular exercise consistent with the current national exercise guidelines for adult patients with cancer (≥ 9 MET-h/wk).30 Our data, however, clearly indicate a strong dose-response relationship suggesting that exercise participation beyond this minimal recommendation may be associated with greater reductions in CVD incidence; this level of exercise can be effectively achieved in the oncology setting via appropriate screening and exercise prescription.31,32 Nevertheless, at present, at least in the United States, exercise treatment is not considered an aspect of first-line therapy for the adverse CV consequences of breast cancer adjuvant therapy, similar to that for the primary or secondary prevention of CVD.33-35 As such, confirmatory data from randomized trials are urgently required. Promising data indicate that structured aerobic training after traditional exercise prescription guidelines is associated with significant improvements in measures of exercise capacity in women with nonmetastatic breast cancer,30 an established, strong predictor of CV morbidity and mortality.36,37 In women without breast cancer, aerobic training improves diastolic filling and increases stroke volume, leading to augmentation of cardiac output.38-40 Aerobic training attenuates pathologic left ventricular remodeling, which may be of particular importance in women with breast cancer given the heightened risk of systolic dysfunction from anthracycline as well as trastuzumab-containing chemotherapy.20 Improvements in the peak arteriovenous oxygen difference demonstrate that aerobic training confers favorable effects beyond the heart via improvements in peripheral vascular and/or increased oxygen use in the skeletal muscles (via enhanced capillary surface area and oxidative capacity).41 In concert, these physiologic adaptations augment oxygen delivery and/or use, measured as augmentation of exercise capacity. These improvements occur in conjunction with significant improvements in traditional as well as conventional CVD risk factors (eg, hypertension, insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia). Similar mechanisms likely underpin the powerful reductions in CVD incidence observed here, although scant evidence is currently available.42

The limitations of our study require consideration. Exercise was assessed by a self-administered questionnaire with well-known limitations, and therefore some misclassification of exposure as well as residual confounding through the impact of other lifestyle factors is likely. To minimize reverse causality, we performed multivariable analyses that controlled for numerous confounding variables as well as excluded patients with CVD before study enrollment. However, as expected, the age, BMI, smoking status, and race were significantly different among women reporting regular exercise versus those who did not. Only data from randomized controlled trials can adequately address this concern. Another important limitation is that use of time since diagnosis in the regression models may confound the relationship between exercise and CV events, because it is also associated with risk of CV events. Our study questionnaire only assessed exercise exposure at one time point shortly after the primary diagnosis of breast cancer; the relationship between lifetime exercise exposure and/or change in exercise levels and CV events could not be addressed. Finally, coding of CVD events using ICD codes is prone to misclassification, potentially resulting in overestimation of CV events.

In summary, exercise is associated with substantial, graded reductions in the incidence of CVD events, the predominant cause of premature morbidity and mortality in women with nonmetastatic breast cancer. These findings are of immediate clinical importance given the large and rapidly growing population of breast cancer survivors at high risk of late-occurring CVD.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Institutes of Health Awards R01CA129059 (B.J.C.), R01CA105274 (L.H.K.), and research grants from the National Cancer Institute and the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Support Grant/Core Grant No. P30 CA008748 (L.W.J.). The Utah Cancer Registry is funded by Contract No. HHSN261201000026C from the National Cancer Institute’s SEER Program, with additional support from the Utah State Department of Health and the University of Utah.

Authors’ disclosures of potential conflicts of interest are found in the article online at www.jco.org. Author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Lee W. Jones, Erin Weltzien, Bette J. Caan

Collection and assembly of data: Lee W. Jones, Laurel A. Habel, Adrienne Castillo, Marilyn L. Kwan, Charles P. Quesenberry Jr, Barbara Sternfeld, Lawrence H. Kushi, Bette J. Caan

Data analysis and interpretation: Lee W. Jones, Laurel A. Habel, Erin Weltzien, Dipti Gupta, Candyce H. Kroenke, Marilyn L. Kwan, Charles P. Quesenberry Jr, Jessica Scott, Barbara Sternfeld, Anthony Yu, Lawrence H. Kushi, Bette J. Caan

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS’ DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Exercise and Risk of Cardiovascular Events in Women With Nonmetastatic Breast Cancer

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jco.ascopubs.org/site/ifc.

Lee W. Jones

Stock or Other Ownership: Exercise by Science

Laurel A. Habel

Research Funding: Genentech (Inst), Takeda Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Sanofi (Inst)

Erin Weltzien

No relationship to disclose

Adrienne Castillo

No relationship to disclose

Dipti Gupta

No relationship to disclose

Candyce H. Kroenke

No relationship to disclose

Marilyn L. Kwan

No relationship to disclose

Charles P. Quesenberry Jr

No relationship to disclose

Jessica Scott

No relationship to disclose

Barbara Sternfeld

No relationship to disclose

Anthony Yu

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Clovis Oncology (I), AstraZeneca (I)

Research Funding: Clovis Oncology (I), AstraZeneca (I), Incyte (I), Astellas Pharma (I)

Lawrence H. Kushi

No relationship to disclose

Bette J. Caan

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Jatoi I, Chen BE, Anderson WF, et al. Breast cancer mortality trends in the United States according to estrogen receptor status and age at diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1683–1690. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doyle JJ, Neugut AI, Jacobson JS, et al. Chemotherapy and cardiotoxicity in older breast cancer patients: A population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8597–8605. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.5841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chapman JA, Meng D, Shepherd L, et al. Competing causes of death from a randomized trial of extended adjuvant endocrine therapy for breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:252–260. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanrahan EO, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Giordano SH, et al. Overall survival and cause-specific mortality of patients with stage T1a,bN0M0 breast carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4952–4960. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.0499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patnaik JL, Byers T, DiGuiseppi C, et al. Cardiovascular disease competes with breast cancer as the leading cause of death for older females diagnosed with breast cancer: A retrospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R64. doi: 10.1186/bcr2901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hooning MJ, Botma A, Aleman BM, et al. Long-term risk of cardiovascular disease in 10-year survivors of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:365–375. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moslehi J. The cardiovascular perils of cancer survivorship. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1055–1056. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1215300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lichtman SM, Hurria A, Jacobsen PB. Geriatric oncology: An overview. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2521–2522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones LW, Haykowsky MJ, Swartz JJ, et al. Early breast cancer therapy and cardiovascular injury. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1435–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Warburton DE, Nicol CW, Bredin SS: Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. CMAJ 174:801-809, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Kwan G, Balady GJ. Cardiac rehabilitation 2012: Advancing the field through emerging science. Circulation. 2012;125:e369–e373. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.093310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caan B, Sternfeld B, Gunderson E, et al. Life After Cancer Epidemiology (LACE) Study: A cohort of early stage breast cancer survivors (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16:545–556. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-8340-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwan ML, Ambrosone CB, Lee MM, et al. The Pathways study: A prospective study of breast cancer survivorship within Kaiser Permanente Northern California. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:1065–1076. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9170-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sternfeld B, Weltzien E, Quesenberry CP, Jr, et al. Physical activity and risk of recurrence and mortality in breast cancer survivors: Findings from the LACE study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:87–95. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, et al. 2011 Compendium of Physical Activities: A second update of codes and MET values. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:1575–1581. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Groarke JD, Cheng S, Moslehi J. Cancer-drug discovery and cardiovascular surveillance. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1779–1781. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1313140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breslow NE. Discussion of Professor Cox’s paper. J Royal Stat Soc B. 1972;34:216–217. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lahart IM, Metsios GS, Nevill AM, et al. Physical activity, risk of death and recurrence in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Acta Oncol. 2015;54:635–654. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2014.998275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ballard-Barbash R, Friedenreich CM, Courneya KS, et al. Physical activity, biomarkers, and disease outcomes in cancer survivors: A systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:815–840. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeh ET, Bickford CL. Cardiovascular complications of cancer therapy: Incidence, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:2231–2247. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khouri MG, Douglas PS, Mackey JR, et al. Cancer therapy-induced cardiac toxicity in early breast cancer: Addressing the unresolved issues. Circulation. 2012;126:2749–2763. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.100560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang S, Liu X, Bawa-Khalfe T, et al. Identification of the molecular basis of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Nat Med. 2012;18:1639–1642. doi: 10.1038/nm.2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manson JE, Greenland P, LaCroix AZ, et al. Walking compared with vigorous exercise for the prevention of cardiovascular events in women. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:716–725. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manson JE, Hu FB, Rich-Edwards JW, et al. A prospective study of walking as compared with vigorous exercise in the prevention of coronary heart disease in women. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:650–658. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908263410904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu FB, Willett WC, Li T, et al. Adiposity as compared with physical activity in predicting mortality among women. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2694–2703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koelwyn GJ, Khouri M, Mackey JR, et al. Running on empty: Cardiovascular reserve capacity and late effects of therapy in cancer survivorship. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4458–4461. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.0891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slamon D, Eiermann W, Robert N, et al. Adjuvant trastuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1273–1283. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Solomon C, et al. Physical activity and risk for cardiovascular events in diabetic women. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:96–105. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-2-200101160-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zagar TM, Cardinale DM, Marks LB. Breast cancer therapy-associated cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13:172–184. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:1409–1426. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0c112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sasso JP, Eves ND, Christensen JF, et al. A framework for prescription in exercise-oncology research. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2015;6:115–124. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones LW, Eves ND, Peppercorn J. Pre-exercise screening and prescription guidelines for cancer patients. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:914–916. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70184-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shephard RJ, Balady GJ. Exercise as cardiovascular therapy. Circulation. 1999;99:963–972. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.7.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Franklin B, Bonzheim K, Warren J, et al. Effects of a contemporary, exercise-based rehabilitation and cardiovascular risk-reduction program on coronary patients with abnormal baseline risk factors. Chest. 2002;122:338–343. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.1.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alfano CM, Ganz PA, Rowland JH, et al. Cancer survivorship and cancer rehabilitation: Revitalizing the link. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:904–906. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gulati M, Pandey DK, Arnsdorf MF, et al. Exercise capacity and the risk of death in women: The St James Women Take Heart Project. Circulation. 2003;108:1554–1559. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000091080.57509.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blair SN, Kampert JB, Kohl HW, III, et al. Influences of cardiorespiratory fitness and other precursors on cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in men and women. JAMA. 1996;276:205–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fujimoto N, Prasad A, Hastings JL, et al. Cardiovascular effects of 1 year of progressive and vigorous exercise training in previously sedentary individuals older than 65 years of age. Circulation. 2010;122:1797–1805. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.973784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ventura-Clapier R, Mettauer B, Bigard X. Beneficial effects of endurance training on cardiac and skeletal muscle energy metabolism in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;73:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hambrecht R, Fiehn E, Weigl C, et al. Regular physical exercise corrects endothelial dysfunction and improves exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 1998;98:2709–2715. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.24.2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haykowsky MJ, Brubaker PH, Stewart KP, et al. Effect of endurance training on the determinants of peak exercise oxygen consumption in elderly patients with stable compensated heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scott JM, Koelwyn GJ, Hornsby WE, et al. Exercise therapy as treatment for cardiovascular and oncologic disease after a diagnosis of early-stage cancer. Semin Oncol. 2013;40:218–228. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]