Abstract

Purpose

Although nonpharmacologic anti-infective measures are widely used in children treated for acute myeloid leukemia (AML), there is little evidence of their effectiveness.

Patients and Methods

We analyzed infectious complications in children during intensive treatment of AML according to the AML-BFM 2004 trial and surveyed sites on institutional standards regarding recommended restrictions of social contacts (six items), pets (five items), and food (eight items). A scoring system was developed with a restriction score for each item. Multivariable Poisson regression adjusted for sex, age, weight group, risk stratification, and prophylactic antibiotics was used to estimate the impact of the restrictions on the incidence ratios of fever of unknown origin, bacteremia, pneumonia, and gastroenteritis.

Results

Data on recommendations of nonpharmacologic anti-infective measures and infectious complications were available in 339 patients treated in 37 institutions. Analyses did not demonstrate a significant benefit of any of the restrictions regarding food, social contacts, and pets on the risk of fever, bacteremia, pneumonia, and gastroenteritis. In contrast, age, weight group, risk stratification, and nonabsorbable antibiotics had some influence on infections complications.

Conclusion

The lack of effectiveness of dietary restrictions and restrictions regarding social contacts and pets should result in reconsideration of anti-infective policies.

INTRODUCTION

Infectious complications are an important cause of morbidity and mortality in patients undergoing therapy for acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The especially high risk for infections in this patient population is a result of the intensive chemotherapeutic regimen, which profoundly disrupts the different arms of the immune system.1,2 To decrease the risk of infection, nonpharmacologic anti-infective measures (eg, restriction of social contacts and food), pharmacologic supportive care (eg, antibacterial and antifungal compounds), and immunomodulation (eg, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor) are widely used.3 Unfortunately, in contrast to well-established and evidence-based guidelines for pharmacologic and immunomodulatory supportive care measures,4-6 there are insufficient data regarding the effectiveness of nonpharmacologic measures, which are important because nonpharmacologic measures may decrease the quality of life for both patients and their families.7

The multi-institutional randomized AML-BFM 2004 (Therapy-Optimization Trial for the Treatment of Acute Myeloid Leukemias [AML] in Children and Adolescents) pediatric trial enrolled patients between March 2004 and April 2010. The primary objective was to improve prognosis by intensification of chemotherapy without increasing toxicity.8 Data regarding infectious complications of a total of 466 patients were gathered in the hospital where the patient had been treated, and part of this analysis has been reported recently.9

In 2010, we performed an international survey in 27 countries on restricting social contacts, pets at home, and food for children with AML.10 The survey demonstrated a wide variation in recommendations regarding nonpharmacologic anti-infective measures between different institutions, countries, and continents. Because 37 of the surveyed centers were located in Germany and were treating patients according to AML-BFM 2004, we consequently had an intention-to-treat measure of nonpharmacologic anti-infective measures by these centers and sought to determine how institutional policies regarding restrictions of social contacts, pets, and food affected the incidence of infectious complications in pediatric AML.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Treatment According to AML-BFM 2004

The multicenter AML-BFM 2004 clinical trial was performed between March 2004 and April 2010 in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and the Czech Republic and enrolled a total of 799 patients (Fig 1). The study was approved by the national ethics committees and the institutional review boards of each center. After providing written consent, patients with de novo AML who were younger than age 18 years were included. Standard-risk (SR) and high-risk (HR) groups were defined as previously described.8 Patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia and patients with Down syndrome received therapy similar to that in the SR group and were included in the protocol (Data Supplement). In brief, both groups received induction chemotherapy consisting of cytarabine, etoposide, and anthracyclines. Only HR patients received a second induction with high-dose cytarabine and mitoxantrone. In HR patients, standard consolidation consisting of cytarabine plus idarubicin was randomly compared with intensification adding 2-chloro-2-deoxyadenosine. Induction in SR patients as well as consolidation in HR patients was followed by a short chemotherapy cycle with cytarabine and idarubicin. All patients received intensification with high-dose cytarabine and etoposide (Appendix, online only).

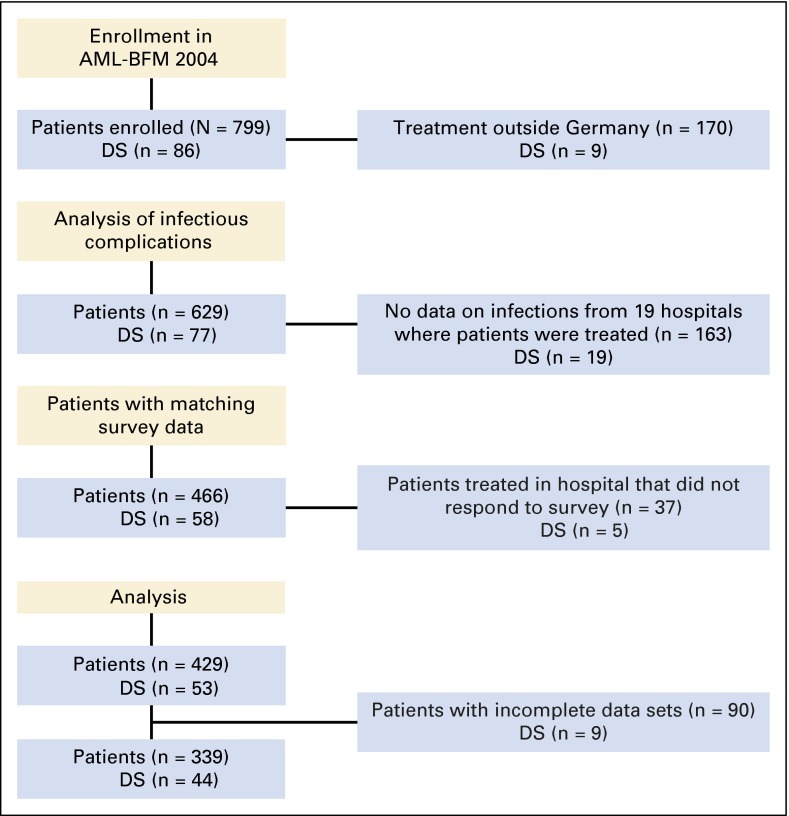

Fig 1.

CONSORT diagram showing the flow of patients from enrollment in the randomized multicenter AML-BFM 2004 trial to the selection of patients according to data on infectious complications and data from a survey on nonpharmacologic anti-infective measures and analysis. DS, Down syndrome.

Specific recommendations regarding diagnostic procedures of infectious complications and supportive care measures such as antimicrobial prophylaxis or empirical therapy were included in the study protocol but were not mandatory. The administration of mold-active antifungal prophylaxis was recommended, whereas no general recommendation regarding antibacterial prophylaxis was given. The routine use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor was discouraged.11,12

Outcomes

Data on infectious complications were abstracted in the hospital where the patient had been treated. Data were collected for the time period of intensive therapy for AML. Only complete data sets were included in the analysis. Infections were defined as clinical signs and symptoms of infection associated with the institution of antibiotics, the isolation of a pathogen, or an identifiable site of infection by physical examination or imaging study.2,9 Infectious episodes were categorized as fever of unknown origin (FUO) or as clinically or microbiologically documented infection. Fever was defined as having a temperature above 38.5°C once or 38°C to 38.5°C twice within a 4-hour interval.2,9 Bacteremia was defined as fever with a positive blood culture for bacteria. If the bloodstream isolate was a potential skin contaminant (eg, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus), the presence of an intravascular catheter was required for the diagnosis of a bloodstream infection.2,13 Infection of the GI tract (gastroenteritis) was diagnosed only when clinical symptoms were associated with the recovery of a pathogen (eg, Clostridium difficile), whereas diarrhea alone or the isolation of a pathogen in the stool without clinical symptoms did not fulfill the criteria for gastroenteritis. The diagnosis of pneumonia required a pathologic chest x-ray and/or computed tomography scan accompanied by clinical symptoms of lower respiratory tract infection.

For weight group classification, body mass index (BMI) percentile at diagnosis for patients age 2 years or older or weight-for-length percentiles were used as previously described.14 Underweight was defined as BMI below the 5th percentile, normal weight as BMI between the 5th and 95th percentiles, and overweight as BMI above the 95th percentile.

Survey

A total of 43 German institutions were surveyed as part of an international, Web-based survey of nonpharmacologic anti-infective measures.10 The survey was developed by the investigators and was extensively pilot tested before dissemination. The survey included questions on institutional recommendations regarding restriction of social contacts, pets at home, and food. Social restrictions evaluated were related to indoor public places, outdoor public places, friends visiting at home, daycare centers, kindergarten, and school beyond kindergarten. Pet restrictions evaluated were related to dogs, cats, turtles, hamsters or guinea pigs, and birds at home. Food restrictions evaluated were related to raw seafood or meat, unpasteurized milk or cheese, uncooked or unpeeled vegetables, salad, nuts, take-out food, and tap water. Activity restrictions were categorized as always restricted, restricted under certain circumstances, or never restricted. For analysis, a scoring system was developed in which each question received a score of 2 for always restricted, 1 for restricted under certain circumstances, and 0 for never restricted, thus creating a summary variable restriction score for social contacts, pets at home, and food.7 The summary restriction score had a maximum score of 12 for social contacts (six items), 16 for food (eight items), and 10 for pets (five items), with higher numbers representing more restrictions.

The survey was sent via e-mail to each institution, typically to the head of pediatric hematology/oncology. Up to two reminders were sent to those who did not respond. The survey was approved by institutional review boards where required; in most centers, however, the ethical committee did not require formal approval to perform the survey.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed by using R 3.1.1 software (http://www.R-project.org/). Poisson regression and associated 95% CIs were used to estimate the impact of social scores, food scores, and pet scores on the incidence rate ratios (IRRs) of infectious complications occurring during the time of intensive treatment for AML. Similarly, multivariable Poisson regressions considering sex, age, weight group, risk stratification, and the prophylactic use of systemic and nonabsorbable antibiotics were performed for adjusted values. A two-sided P value < .05 was regarded as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Of 43 German pediatric hematology centers, 37 (86%) responded to the survey. A total of 629 children were treated in German institutions according to the AML-BFM 2004 clinical trial. In 466 (74%) of these 629 patients, data on infectious complications were available (Fig 1). Of these 466 patients, 429 were treated in one of the institutions responding to the survey, with complete data sets for 339 children who were further analyzed. Demographic characteristics of patients from institutions that replied to the survey are listed in Table 1. In each institution, a median of 11 patients (range, four to 28 patients) were treated according to AML-BFM 2004. Prophylactic nonabsorbable antibiotics were administered to 123 patients (36%), and 100 patients (29.5%) received systemic antibacterial prophylaxis, mostly with penicillin (n = 71) but also with fluoroquinolones, teicoplanin, or meropenem. Systemic antifungal prophylaxis was given to a majority of patients (n = 319 [94.1%]; Table 1). Regarding the outcome parameters, 277 patients (81.7%) experienced at least one episode of FUO, and 174 (51.3%), 45 (13.3%), and 77 (22.7%) of the patients had at least one episode of bacteremia, pneumonia, or gastroenteritis, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Children With AML Enrolled in the AML-BFM 2004 Clinical Trial Who Were Treated at Institutions That Responded to the Survey

| Characteristic | All Patients (N = 339) | Patients With Antifungal Prophylaxis (n = 319) | Patients With Systemic Antibacterial Prophylaxis (n = 100) | Patients With Nonabsorbable Antibiotic Prophylaxis (n = 123) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 168 | 50 | 155 | 92 | 45 | 27 | 47 | 28 |

| Female | 171 | 50 | 164 | 96 | 55 | 32 | 76 | 44 |

| Down syndrome | ||||||||

| Yes | 44 | 13 | 40 | 91 | 10 | 23 | 15 | 34 |

| No | 295 | 87 | 279 | 95 | 90 | 31 | 108 | 37 |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| 0 to < 2 | 94 | 28 | 89 | 95 | 28 | 30 | 34 | 36 |

| 2 to < 7 | 79 | 23 | 76 | 96 | 22 | 28 | 28 | 35 |

| 7 to < 11 | 34 | 10 | 28 | 82 | 8 | 24 | 12 | 35 |

| 11 to ≤ 18 | 132 | 39 | 126 | 95 | 42 | 32 | 49 | 30 |

| Weight group | ||||||||

| Underweight | 54 | 16 | 52 | 96 | 11 | 20 | 17 | 31 |

| Normal weight | 248 | 73 | 232 | 94 | 79 | 32 | 91 | 37 |

| Overweight | 26 | 8 | 24 | 92 | 5 | 19 | 12 | 46 |

| Unknown | 11 | 3 | 11 | 100 | 5 | 45 | 3 | 27 |

| FAB classification | ||||||||

| M0 | 10 | 3 | 9 | 90 | 2 | 20 | 6 | 60 |

| M1 | 36 | 11 | 35 | 97 | 14 | 39 | 12 | 33 |

| M2 | 69 | 20 | 65 | 94 | 20 | 29 | 25 | 36 |

| M3 | 25 | 7 | 23 | 92 | 4 | 16 | 9 | 36 |

| M4 | 65 | 19 | 61 | 94 | 22 | 34 | 24 | 37 |

| M5 | 60 | 18 | 58 | 97 | 22 | 37 | 22 | 37 |

| M6 | 7 | 2 | 6 | 86 | 2 | 29 | 2 | 29 |

| M7 | 64 | 19 | 60 | 94 | 14 | 22 | 22 | 34 |

| Unknown | 3 | 1 | 2 | 67 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 33 |

| Risk group | ||||||||

| Standard risk | 139 | 41 | 132 | 95 | 37 | 27 | 74 | 53 |

| High risk | 199 | 59 | 186 | 93 | 62 | 31 | 48 | 24 |

| Unknown | 1 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

NOTE. Details for weight groups and risk groups are provided in Patients and Methods.

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; FAB, French-American-British.

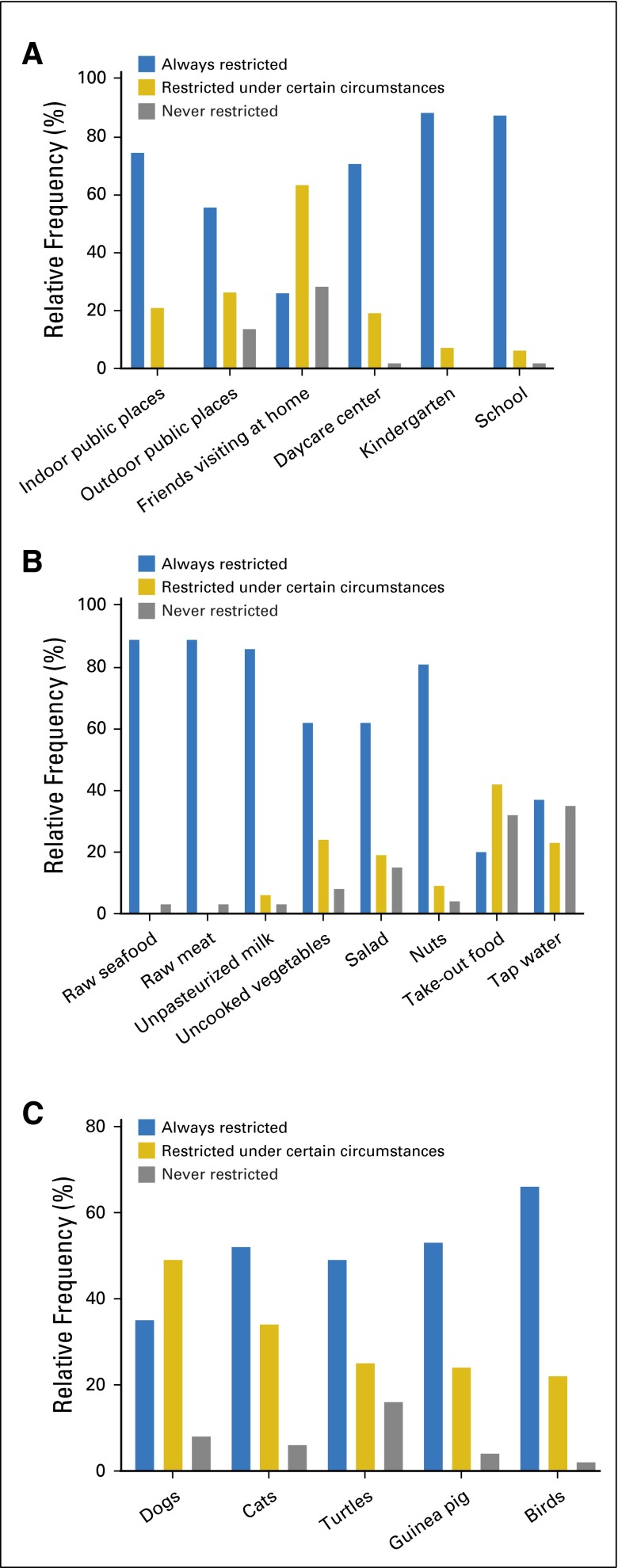

There was a wide variety regarding the frequencies of restrictions in the different categories (Appendix Fig A1, online only). Restrictions in all circumstances were recommended in more than 90% of the patients for attending kindergarten or school, and in more than 80% of the patients for eating raw seafood or meat. In contrast, restrictions in all circumstances for friends visiting at home or consuming take-out food were recommended in less than one third of the patients. Regarding social restrictions with six items and consequently the highest possible score of 12, the median score observed in the centers analyzed was 9 (range, 7 to 12). Regarding restrictions of pets (five items; highest possible score, 10), median score was 8 (range, 2 to 10); for restrictions of food (eight items; highest possible score, 16), median score was 14 (range, 0 to 16).

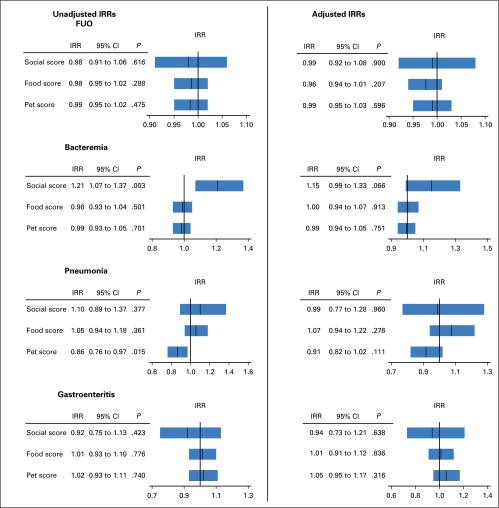

Multivariable regression analysis not adjusted for potential confounders such as sex, age, weight group, risk stratification, or antibiotic prophylaxis demonstrated that a higher restriction score regarding social contacts was significantly associated with an increased incidence of bacteremia (IRR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.07 to 1.37; P = .003), whereas higher restriction scores of pets at home were significantly associated with a decreased incidence of pneumonia (IRR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.76 to 0.97; P = .015; Fig 2). However, when including adjustment for sex, age, weight groups, risk stratification, and antibiotic prophylaxis in the multivariable regression analysis, none of the restriction scores regarding social contacts, pets at home, and food were significantly associated with the risk of FUO, bacteremia, pneumonia, and gastroenteritis (Fig 2). In contrast, multivariable regression analysis adjusted for potential confounders demonstrated that patients who were underweight had an increased risk for FUO compared with children who were normal weight (adjusted IRR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.65 to 0.97; P = .028) or overweight (IRR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.38 to 0.80; P = .002; Table 2). The risk for bacteremia was significantly associated with risk stratification and the prophylactic use of nonabsorbable antibiotics. HR patients had a significantly higher risk of bacteremia than SR patients (adjusted IRR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.20 to 2.10; P = .001), whereas the prophylactic use of nonabsorbable antibiotics was associated with a decreased risk for bacteremia (adjusted IRR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.43 to 0.80; P = .001; Table 3). Similarly, HR patients had a significantly increased risk for pneumonia (adjusted IRR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.03 to 3.60; P = .039; Table 4). The risk for gastroenteritis was significantly associated with age, with lower risk in older children (adjusted IRR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.90 to 0.98; P = .008; Table 5).

Fig 2.

Multivariable Poisson regression evaluating the influence of restricting social contacts, food, and pets on infectious complications in children with acute myeloid leukemia. The summary of multivariable analyses of restrictions of social contacts (social score), food (food score), and pets at home (pet score) affecting the incidence of fever of unknown origin (FUO), bacteremia, pneumonia, and gastroenteritis. Shown are the incidence rate ratios (IRRs) with 95% CIs considering only social, food, and pets scores (left side), and IRRs for multivariable analyses that included adjustment for sex, age, weight group, risk stratification, and prophylactic antibiotics (right side). The bar in each box represents the IRR, and the box represents the corresponding 95% CI. The vertical line represents IRR = 1 for reference.

Table 2.

Multivariable Poisson Regression Evaluating the Influence of Restricting Social Contacts (social score), Food (food score), and Pets (pet score) on the Incidence of FUO in Children With AML

| Variable | Adjusted IRR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social score | 0.99 | 0.92 to 1.08 | .900 |

| Food score | 0.96 | 0.94 to 1.01 | .207 |

| Pet score | 0.99 | 0.95 to 1.03 | .596 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1 | ||

| Female | 1.17 | 0.98 to 1.39 | .079 |

| Age (years) | 1.0 | 0.98 to 1.01 | .716 |

| BMI percentile | |||

| Below 5th | 1 | ||

| 5th to 95th | 0.79 | 0.65 to 0.97 | .028 |

| Above 95th | 0.55 | 0.38 to 0.80 | .002 |

| Risk group | |||

| SR | 1 | ||

| HR | 1.12 | 0.95 to 1.32 | .171 |

| Prophylaxis with systemic antibiotics | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.94 | 0.76 to 1.16 | .568 |

| Prophylaxis with nonabsorbable antibiotics | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.92 | 0.77 to 1.10 | .365 |

NOTE. Details for weight groups and risk groups are provided in Patients and Methods.

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BMI, body mass index; FUO, fever of uncertain origin; HR, high risk; IRR, incidence rate ratio; SR, standard risk.

Table 3.

Multivariable Poisson Regression Evaluating the Influence of Restricting Social Contacts (social score), Food (food score), and Pets (pet score) on the Incidence of Bacteremia in Children With AML

| Variable | Adjusted IRR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social score | 1.15 | 0.99 to 1.33 | .066 |

| Food score | 1.00 | 0.94 to 1.07 | .913 |

| Pet score | 0.99 | 0.94 to 1.05 | .751 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1 | ||

| Female | 0.99 | 0.77 to 1.27 | .951 |

| Age (years) | 1.02 | 1.00 to 1.05 | .056 |

| BMI percentile | |||

| Below 5th | 1 | ||

| 5th to 95th | 1.26 | 0.84 to 1.89 | .272 |

| Above 95th | 1.24 | 0.62 to 2.46 | .542 |

| Risk group | |||

| SR | 1 | ||

| HR | 1.59 | 1.20 to 2.10 | .001 |

| Prophylaxis with systemic antibiotics | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.79 | 0.55 to 1.13 | .188 |

| Prophylaxis with nonabsorbable antibiotics | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.59 | 0.43 to 0.80 | .001 |

NOTE. Details for weight groups and risk groups are provided in Patients and Methods.

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BMI, body mass index; HR, high risk; IRR, incidence rate ratio; SR, standard risk.

Table 4.

Multivariable Poisson Regression Evaluating the Influence of Restricting Social Contacts (social score), Food (food score), and Pets (pet score) on the Incidence of Pneumonia in Children With AML

| Variable | Adjusted IRR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social score | 0.99 | 0.77 to 1.28 | .960 |

| Food score | 1.07 | 0.94 to 1.22 | .276 |

| Pet score | 0.91 | 0.82 to 1.02 | .111 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1 | ||

| Female | 1.14 | 0.65 to 1.98 | .646 |

| Age (years) | 0.99 | 0.94 to 1.04 | .635 |

| BMI percentile | |||

| Below 5th | 1 | ||

| 5th to 95th | 0.99 | 0.46 to 2.10 | .971 |

| Above 95th | 0.26 | 0.04 to 1.90 | .185 |

| Risk group | |||

| SR | 1 | ||

| HR | 1.93 | 1.03 to 3.60 | .039 |

| Prophylaxis with systemic antibiotics | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.44 | 0.17 to 1.16 | .097 |

| Prophylaxis with nonabsorbable antibiotics | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.56 | 0.30 to 1.05 | .069 |

NOTE. Details for weight groups and risk groups are provided in Patients and Methods.

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BMI, body mass index; HR, high risk; IRR, incidence rate ratio; SR, standard risk.

Table 5.

Multivariable Poisson Regression Evaluating the Influence of Restricting Social Contacts (social score), Food (food score), and Pets (pet score) on the Incidence of Gastroenteritis in Children With AML

| Variable | Adjusted IRR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social score | 0.94 | 0.73 to 1.21 | .638 |

| Food score | 1.01 | 0.91 to 1.12 | .836 |

| Pet score | 1.05 | 0.95 to 1.17 | .316 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1 | ||

| Female | 0.94 | 0.56 to 1.56 | .806 |

| Age (years) | 0.94 | 0.90 to 0.98 | .008 |

| BMI percentile | |||

| Below 5th | 1 | ||

| 5th to 95th | 1.36 | 0.97 to 1.84 | .058 |

| Above 95th | 0.86 | 0.24 to 3.02 | .814 |

| Risk group | |||

| SR | 1 | ||

| HR | 0.83 | 0.51 to 1.35 | .458 |

| Prophylaxis with systemic antibiotics | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.70 | 0.37 to 1.32 | .268 |

| Prophylaxis with nonabsorbable antibiotics | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.14 | 0.68 to 1.92 | .610 |

NOTE. Details for weight groups and risk groups are provided in Patients and Methods.

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BMI, body mass index; HR, high risk; IRR, incidence rate ratio; SR, standard risk.

DISCUSSION

On the basis of the combination of the results of a survey and of a prospective multi-institutional clinical trial in children undergoing therapy for AML, we did not find that dietary restrictions (neutropenic diet) and restrictions regarding social contacts and pets at home were significantly associated with a decreased incidence of FUO, bacteremia, pneumonia, and gastroenteritis. In contrast, we found that underweight, age, risk stratification, and the prophylactic administration of nonabsorbable antibiotics were specifically associated with the risk of infectious complications.

For decades, the concept of neutropenic diet has implied a strict limitation of foods allowed for patients with cancer, which may considerably decrease the quality of life.7 The theoretical rationale of the neutropenic diet is to limit the introduction of potentially harmful pathogens into the GI tract by restricting certain foods that might harbor those organisms. However, the effectiveness of this strategy has never been proven and is increasingly being questioned.15-17 Although randomized studies demonstrated that stricter rules regarding food restrictions did not decrease the risk of infectious complications, generalization of these data are limited by multiple factors, including single-center study design and small patient populations or selection biases such as high rates of patients declining random assignment, or treatment of randomly assigned patients in high-efficiency particulate air-filtered rooms only.18,19 In contrast, our results reflect an intention-to-treat analysis of nonpharmacologic measures in a large number of children with AML treated in 37 German pediatric hematology oncology centers. Our findings corroborate a recent meta-analysis of four studies encompassing 918 patients with cancer that could not demonstrate superiority of the neutropenic diet with respect to mortality or infection.20 We therefore believe that the consumption of uncooked vegetables, salad, take-out food, and tap water is safe in pediatric patients with cancer in countries with standards of hygiene comparable to that of Germany, and we have changed the policy in our hospital in Frankfurt, Germany, accordingly. However, we did not modify our strict recommendations regarding the consumption of raw meat and unpasteurized milk, which may also pose health risks in individuals who are not immunocompromised.21

There are few studies evaluating the impact of restrictions of social contacts and of pets at home on the risk of infectious complications. Controlled studies are difficult to perform and have a high risk of biased results because of multiple potential confounders such as a patient’s living environment (eg, rural v urban and small apartment v spacious house). However, small observational studies did not find an increased risk of infections in 27 children attending school while undergoing cancer treatment,22 and in 34 severely neutropenic patients with cancer attending a 2-week unprotected recreational overnight summer camp.18 The speculation that these findings may safely be applicable to other social settings supports the strategy that continuing routine daily activities such as attending daycare centers or school is feasible and helpful for short- and long-term well-being of children and their families during treatment of cancer.23 However, it is important to note that our analyses do not relate to patients colonized with resistant pathogens who have to be isolated during hospital admission, which is an essential measure for limiting the spread of these pathogens in an era of reduced antibiotic availability.

Although there are single case reports on the transmission of various pathogens from dogs, cats, or birds causing infectious complications,24-26 our data do not generally support the restriction of pets at home. Our policies include advising patients to seek veterinary surveillance of the animal, washing hands after handling pets, avoiding cleaning cages, and not having contact with reptiles (eg, turtles) to reduce the risk of acquiring salmonellosis, all of which are also recommended in current guidelines.27,28

In contrast to restrictions of social contacts, food, and pets at home, factors such as underweight, age, risk stratification, and the prophylactic administration of nonabsorbable antibiotics seem to be associated with the risk for infection. In line with our findings, some studies report that underweight in children with AML is associated with a higher risk of severe infection and mortality,29-31 and weight loss of > 5% in the first 3 months after diagnosis was related to increased occurrence of febrile neutropenic episodes.32 Although incompletely understood, the increased risk for infection is most likely a result of impaired immunity associated with malnutrition.33 The observation that younger patients had a higher risk for gastroenteritis is not surprising. Similar results were reported for children who were not immunocompromised across different countries and continents, with highest incidence rates for the 6 to 12 months age group.34,35 The incidence and severity of diarrhea as a sign of GI toxicity resulting from chemotherapy was also higher in younger compared with older children with AML,36 which suggests that the damage to the gut from chemotherapy increases the risk for gastroenteritis especially in the younger age group. Corroborating our findings, it has been reported that children with acute lymphatic leukemia and children with AML stratified in the HR group and receiving a more intensive chemotherapy compared with patients in the low-risk or SR group are at higher risk for infectious complications such as bacteremia and pneumonia.37-39

The rationale for using nonabsorbable antibiotics for selective bowel decontamination is that infections resulting from gram-negative pathogens often originate from the GI flora. Although early studies demonstrated some benefit of nonabsorbable antibiotics, current clinical trials primarily investigate these agents in combination with fluoroquinolones or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Therefore, it is not possible to draw a final conclusion because the results are conflicting.40-42 It is also important to note that the duration of exposure to the nonabsorbable antibiotic compound colistin has recently been described as an independent risk factor for the acquisition of carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteremia, which is a major drawback for this strategy.43

Our report has several important strengths and limitations. Our approach is novel, combining the daily practices of pediatric cancer centers with the results of a prospective multi-institutional trial. This approach has recently been applied for the first time,14 and it results in an intention-to-treat measure of supportive care. This strategy is therefore an ideal way to generate data on the effectiveness of nonpharmacologic anti-infective supportive care measures in clinical practice and complements the results of observational studies and randomized trials, all of which have limitations and results that may not be generalizable. We also acknowledge that the results of our analysis must be interpreted with caution for several reasons. First, it is important to note that a nonsignificant P value is not synonymous with conclusions of equivalence. Second, we evaluated our interventions of interest by using an observational design. Such an approach is more susceptible to confounding and other sources of bias. However, our approach is likely the only feasible approach for addressing these important questions because randomized trials of interventions such as pet restrictions are unlikely to be performed. Third, complete data sets on infectious complications and on recommendations of nonpharmacologic anti-infective measures from the hospital where the patient was treated were available in only 339 of 629 patients, which may represent a bias. In addition, despite the availability of individual institutional standards for nonpharmacologic anti-infective prophylaxis, individual patients may have received recommendations that differ from this standard. Even with an onsite review, it is impossible to validate the recommendations individually. Nonadherence to supportive care recommendations, as reported for restrictions of social contact or the use of topical antifungals, could have biased the results of this analysis.7 Finally, the design of our analysis does not permit us to give detailed information on whether nonpharmacologic anti-infective measures may be more important during neutropenia episodes than during nonneutropenic periods, a topic which should be addressed in future studies.

In conclusion, our data suggest that a strict neutropenic diet and strict policies regarding restrictions of social contacts (eg, school attendance) and restrictions of pets at home during intensive chemotherapy for pediatric AML do not decrease the rate of infections. Therefore, changing this strict policy could improve the patients’ quality of life without increasing the risk of infectious complications. Future studies in children with all kinds of malignancies are needed to evaluate the impact of nonpharmacologic measures on the incidence of infections, the immune system, the quality of life, and overall clinical outcome.

Supplementary Material

Appendix

Both standard-risk (SR) and high-risk (HR) groups received induction therapy, which consisted of cytarabine 100 mg/m2/d continuous infusion over 2 days followed by a 30-minute infusion twice per day on days 3 to 8, etoposide 150 mg/m2/d on days 6 to 8 in combination with liposomal daunorubicin 80 mg/m2/d for 3 days or idarubicin 12 mg/m2/d for 3 days by random assignment. Only HR patients received a second induction with high-dose cytarabine 3 g/m2/d for 3 days and mitoxantrone 10 mg/m2/d for 2 days. In HR patients, standard consolidation consisting of 500 mg/m² cytarabine for 4 days continuous infusion plus 7 mg/m²/d idarubicin days 3 and 5 was randomly compared with intensification adding 2-chloro-2-deoxyadenosine 6 mg/m2/d for 2 days. Induction in SR patients as well as consolidation in HR patients was followed by a short chemotherapy cycle with cytarabine and idarubicin. All patients received intensification with high-dose cytarabine 3 g/m2 every 12 hours for 3 days and etoposide 125 mg/m2/d for 4 days as the final intensive course. Intensive therapy was followed by cranial radiation therapy (patients were randomly assigned to 12 or 18 Gy) and by maintenance therapy consisting of thioguanine and cytarabine given for a total treatment duration of 18 months.

Fig A1.

Relative frequencies of recommendations regarding (A) social contacts, (B) food, and (C) pets at home. The y-axis shows the percentage of patients with the specific recommendation.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 47th Congress of the International Society of Paediatric Oncology, Cape Town, South Africa, October 8-11, 2015.

Listen to the podcast by Dr Ammann at www.jco.org/podcasts

Authors’ disclosures of potential conflicts of interest are found in the article online at www.jco.org. Author contributions are found at the end of this article.

Clinical trial information: NCT00111345.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Lars Tramsen, Thomas Klingebiel, Lillian Sung, Thomas Lehrnbecher

Provision of study materials or patients: Dirk Reinhardt, Ursula Creutzig,

Collection and assembly of data: Lars Tramsen, Dirk Reinhardt, Ursula Creutzig, Thomas Lehrnbecher

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS’ DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Lack of Effectiveness of Neutropenic Diet and Social Restrictions as Anti-Infective Measures in Children With Acute Myeloid Leukemia: An Analysis of the AML-BFM 2004 Trial

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jco.ascopubs.org/site/ifc.

Lars Tramsen

No relationship to disclose

Emilia Salzmann-Manrique

No relationship to disclose

Konrad Bochennek

No relationship to disclose

Thomas Klingebiel

Consulting or Advisory Role: Loxo Oncology

Dirk Reinhardt

No relationship to disclose

Ursula Creutzig

No relationship to disclose

Lillian Sung

No relationship to disclose

Thomas Lehrnbecher

Consulting or Advisory Role: Basilea Pharmaceutica, Gilead Sciences, MSD/Merck

Speakers’ Bureau: Astellas Pharma, Gilead Sciences, MSD/Merck

Research Funding: Gilead Sciences

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Astellas Pharma, MSD/Merck, Gilead Sciences, Pfizer

REFERENCES

- 1.Lehrnbecher T, Foster C, Vázquez N, et al. Therapy-induced alterations in host defense in children receiving therapy for cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1997;19:399–417. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199709000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lehrnbecher T, Varwig D, Kaiser J, et al. Infectious complications in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: Analysis of the prospective multi-institutional clinical trial AML-BFM 93. Leukemia. 2004;18:72–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lehrnbecher T, Sung L. Anti-infective prophylaxis in pediatric patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Expert Rev Hematol. 2014;7:819–830. doi: 10.1586/17474086.2014.965140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Science M, Robinson PD, MacDonald T, et al. Guideline for primary antifungal prophylaxis for pediatric patients with cancer or hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:393–400. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Groll AH, Castagnola E, Cesaro S, et al. Fourth European Conference on Infections in Leukaemia (ECIL-4): Guidelines for diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of invasive fungal diseases in paediatric patients with cancer or allogeneic haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e327–e340. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aapro MS, Bohlius J, Cameron DA, et al. 2010 update of EORTC guidelines for the use of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor to reduce the incidence of chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia in adult patients with lymphoproliferative disorders and solid tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:8–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lehrnbecher T, Laws HJ, Boehm A, et al. Compliance with anti-infective preventive measures: A multicentre survey among paediatric oncology patients. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:1861–1865. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Creutzig U, Zimmermann M, Bourquin JP, et al. Randomized trial comparing liposomal daunorubicin with idarubicin as induction for pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: Results from Study AML-BFM 2004. Blood. 2013;122:37–43. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-02-484097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bochennek K, Hassler A, Perner C, et al. Infectious complications in children with acute myeloid leukemia: Decreased mortality in multicenter trial AML-BFM 2004. Blood Cancer J. 2016;6:e382. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2015.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lehrnbecher T, Aplenc R, Rivas Pereira F, et al. Variations in non-pharmacological anti-infective measures in childhood leukemia: Results of an international survey. Haematologica. 2012;97:1548–1552. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.062885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehrnbecher T, Zimmermann M, Reinhardt D, et al. Prophylactic human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor after induction therapy in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2007;109:936–943. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-035915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ehlers S, Herbst C, Zimmermann M, et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) treatment of childhood acute myeloid leukemias that overexpress the differentiation-defective G-CSF receptor isoform IV is associated with a higher incidence of relapse. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2591–2597. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wisplinghoff H, Seifert H, Wenzel RP, et al. Current trends in the epidemiology of nosocomial bloodstream infections in patients with hematological malignancies and solid neoplasms in hospitals in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:1103–1110. doi: 10.1086/374339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sung L, Aplenc R, Alonzo TA, et al. Effectiveness of supportive care measures to reduce infections in pediatric AML: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Blood. 2013;121:3573–3577. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-476614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moody K, Charlson ME, Finlay J. The neutropenic diet: What’s the evidence? J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2002;24:717–721. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200212000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox N, Freifeld AG. The neutropenic diet reviewed: Moving toward a safe food handling approach. Oncology (Williston Park) 2012;26:572–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boeckh M. Neutropenic diet: Good practice or myth? Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:1318–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tabori U, Jones H, Malkin D. Low prevalence of complications in severe neutropenic children with cancer in the unprotected environment of an overnight camp. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:148–151. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardner A, Mattiuzzi G, Faderl S, et al. Randomized comparison of cooked and noncooked diets in patients undergoing remission induction therapy for acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5684–5688. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.4681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sonbol MB, Firwana B, Diab M, et al. The effect of a neutropenic diet on infection and mortality rates in cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Nutr Cancer. 2015;67:1230–1238. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2015.1082109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Raw milk may pose health risk. http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm232980.htm.

- 22. af Sandeberg M, Wettergren L, Björk O, et al: Does school attendance during initial cancer treatment in childhood increase the risk of infection? Pediatr Blood Cancer 60:1307-1312, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Breen M, Coombes L, Bradbourne C. Supportive care for children and young people during cancer treatment. Community Pract. 2009;82:28–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yacoub AT, Katayama M, Tran J, et al. Bordetella bronchiseptica in the immunosuppressed population: A case series and review. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2014;6:e2014031. doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2014.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duhautois J, Chabrol J, Terce G, et al. [Unusual pneumonia by Pasteurella multocida] [in French] Rev Pneumol Clin. 2013;69:46–49. doi: 10.1016/j.pneumo.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fouchier RA, Rimmelzwaan GF, Kuiken T, et al. Newer respiratory virus infections: Human metapneumovirus, avian influenza virus, and human coronaviruses. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2005;18:141–146. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000160903.56566.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Exner M, Maschmeyer G, Christiansen B, et al. Kommission für Krankenhaushygiene und Infektionsprävention beim Rober Koch-Institut (RKI): Anforderungen an die Hygiene bei der medizinischen Versorgung von immunsupprimierten Patienten. Bundesgesundheitsbl. 2010;53:357–388. doi: 10.1007/s00103-010-1028-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. doi: 10.1016/S1083-8791(00)70002-4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Infectious Diseases Society of America; American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation: Guidelines for preventing opportunistic infections among hematopoietic stem cell transplant trecipients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 6:7-83, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inaba H, Surprise HC, Pounds S, et al. Effect of body mass index on the outcome of children with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2012;118:5989–5996. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lange BJ, Gerbing RB, Feusner J, et al. Mortality in overweight and underweight children with acute myeloid leukemia. JAMA. 2005;293:203–211. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sung L, Lange BJ, Gerbing RB, et al. Microbiologically documented infections and infection-related mortality in children with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2007;110:3532–3539. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-091942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loeffen EA, Brinksma A, Miedema KG, et al. Clinical implications of malnutrition in childhood cancer patients: Infections and mortality. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:143–150. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2350-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rytter MJ, Kolte L, Briend A, et al. The immune system in children with malnutrition: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fischer Walker CL, Perin J, Aryee MJ, et al. Diarrhea incidence in low- and middle-income countries in 1990 and 2010: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:220. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lenzi J, Luciano L, McDonald KM, et al. Empirical examination of the indicator ‘pediatric gastroenteritis hospitalization rate’ based on administrative hospital data in Italy. Ital J Pediatr. 2014;40:14. doi: 10.1186/1824-7288-40-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Webb DK, Harrison G, Stevens RF, et al. Relationships between age at diagnosis, clinical features, and outcome of therapy in children treated in the Medical Research Council AML 10 and 12 trials for acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2001;98:1714–1720. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.6.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Castagnola E, Caviglia I, Pistorio A, et al. Bloodstream infections and invasive mycoses in children undergoing acute leukaemia treatment: A 13-year experience at a single Italian institution. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:1439–1445. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graubner UB, Porzig S, Jorch N, et al. Impact of reduction of therapy on infectious complications in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:259–263. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sung L, Gamis A, Alonzo TA, et al. Infections and association with different intensity of chemotherapy in children with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2009;115:1100–1108. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schimpff SC. Laminar air flow room reverse isolation and microbial suppression to prevent infection in patients with cancer. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1975;59:1055–1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee DG, Choi SM, Choi JH, et al. Selective bowel decontamination for the prevention of infection in acute myelogenous leukemia: A prospective randomized trial. Korean J Intern Med. 2002;17:38–44. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2002.17.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brunet AS, Ploton C, Galambrun C, et al. Low incidence of sepsis due to viridans streptococci in a ten-year retrospective study of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;47:765–772. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Routsi C, Pratikaki M, Platsouka E, et al. Risk factors for carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteremia in intensive care unit patients. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:1253–1261. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-2914-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.