Policy Points:

E‐cigarettes are new products that are generating policy issues, including youth access and smokefree laws, for local and state governments.

Unlike with analogous debates on conventional cigarettes, initial opposition came from e‐cigarette users and retailers independent of the multinational cigarette companies.

After the cigarette companies entered the e‐cigarette market, the opposition changed to resemble long‐standing industry resistance to tobacco control policies, including campaign contributions, lobbying, and working through third parties and front groups.

As with earlier efforts to restrict tobacco products, health advocates have had the most success at the local rather than the state level.

Context

E‐cigarettes entered the US market in 2007 without federal regulation. In 2009, local and state policymakers began identifying ways to regulate their sale, public usage, taxation, and marketing, often by integrating them into existing tobacco control laws.

Methods

We reviewed legislative hearings, newspaper articles, financial disclosure reports, NewsBank, Google, Twitter, and Facebook and conducted interviews to analyze e‐cigarette policy debates between 2009 and 2014 in 4 cities and the corresponding states.

Findings

Initial opposition to local and state legislation came from e‐cigarette users and retailers independent of the large multinational cigarette companies. After cigarette companies entered the e‐cigarette market, e‐cigarette policy debates increasingly resembled comparable tobacco control debates from the 1970s through the 1990s, including pushing pro‐industry legislation, working through third parties and front groups, mobilizing “grassroots” networks, lobbying and using campaign contributions, and claiming that policy was unnecessary due to “imminent” federal regulation. Similar to the 1980s, when the voluntary health organizations were slow to enter tobacco control debates, because they saw smoking restrictions as controversial, these organizations were reluctant to enter e‐cigarette debates. Strong legislation passed at the local level because of the committed efforts of local health departments and leadership from experienced politicians but failed at the state level due to intense cigarette company lobbying without countervailing pressure from the voluntary health organizations.

Conclusions

Passing e‐cigarette regulations at the state level has become more difficult since cigarette companies have entered the market. While state legislation is possible, as with earlier tobacco control policymaking, local governments remain a viable option for overcoming cigarette company interference in the policymaking process.

Electronic cigarettes (e‐cigarettes), also known as electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), are battery‐operated devices that deliver an aerosol of nicotine (in most cases), flavors, and other chemicals by heating a liquid rather than burning tobacco as a conventional cigarette does. E‐cigarettes exist in a wide variety of forms, including “cigalikes,” which resemble conventional cigarettes, and “open systems” (including “vape pens” and “tanks”) with a greater heating capacity that can be refilled and reused. Most brands offer several flavors, including traditional cigarette flavors (tobacco and menthol), and candy flavors1, 2 (gummy bears, bubble gum, cotton candy) that have been found to be attractive to youth.3, 4 Since e‐cigarettes entered the US market in 2007, they have been promoted as healthier alternatives to conventional cigarettes, as smoking cessation devices, and as socially acceptable products that could be used where conventional cigarettes were prohibited.5 The impact of e‐cigarettes on public health has also been controversial. Some public health experts saw e‐cigarettes as a solution to the tobacco epidemic,6, 7 while others took a precautionary approach to e‐cigarettes based on concerns that e‐cigarettes would complicate efforts to reduce tobacco use.8

The issue of whether e‐cigarettes should be legally defined as tobacco products has been contentious. In 2008, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) attempted to regulate e‐cigarettes under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act as a “combination drug‐device product that requires pre‐approval, registration, and listing with the FDA.”9 The e‐cigarette company Sottera (now known as NJOY) successfully sued the FDA, claiming that e‐cigarettes were tobacco products that could only be regulated under the FDA's new authority to regulate tobacco products. In 2014 the FDA issued a draft rule to assert regulatory authority over e‐cigarettes as tobacco products,10 which was finalized in May 2016. The rule, which brings e‐cigarettes under FDA jurisdiction, will, if it survives legal challenge, allow the FDA to regulate product design and manufacturing, marketing claims, warning labels and packaging, and prohibit sales to youth under 18. FDA jurisdiction preempts state and local governments in these areas (with federal law allowing them to set a higher minimum age), but has no effect on where e‐cigarettes can be used or taxed, setting higher minimum age, or licensing on retailers because these areas are outside FDA jurisdiction.11

Without federal action, the focus of e‐cigarette policymaking shifted to state and local governments, as public health concerns developed, particularly the rapid increase in e‐cigarette use among never‐smoking middle and high school students12, 13 and e‐cigarettes becoming the most popular form of tobacco product among youth.14 While there has been some research on the prevalence of state15, 16 and local e‐cigarette laws,17 including the importance of e‐cigarette product definitions,18, 19 and arguments used in e‐cigarette policymaking for clean indoor air laws,17, 19 there has not been a study of the advocacy process in debates over state and local e‐cigarette policymaking.

Advocacy coalitions consist of actors from public and private organizations concerned with a problem who seek to resolve it by influencing policy change,20, 21 often with competing goals.22 Advocacy coalitions provide a framework to understand regulating e‐cigarette and tobacco products in a complex policy field with potential for conflict between different stakeholders with different sets of beliefs across a wide variety of policies23, 24 (eg, public usage laws and taxation).

This article addresses the question, “How have opposing advocacy coalitions developed and evolved to promote or oppose state and local e‐cigarette policies, with particular emphasis on the policy adoption stage of the policy cycle?”

Methods

We used qualitative case study methodology to analyze e‐cigarette policymaking in 4 cities (New York City, Los Angeles, Duluth, and Chicago) and the corresponding states (New York, California, Minnesota, and Illinois) that held debates on e‐cigarette policy between 2009 and 2014. New York City, Los Angeles, and Chicago were selected because they were identified in the media as areas with e‐cigarette policy activity. Duluth was chosen to allow for observation of how actors operated in a smaller jurisdiction.

Documentary Evidence

We gathered documentary evidence of e‐cigarette policy debates in each jurisdiction, including legislative records, bills, recordings of committee hearings, publicly available lobbying and campaign contribution data, and legislative testimony. We identified local news sources through NewsBank and Google News and reviewed local news stories in newspaper articles to identify actors involved in supporting or opposing proposed e‐cigarette laws. After we identified relevant organizations and people (health departments, health commissioners, school superintendents, voluntary health organizations, e‐cigarette retailers, e‐cigarette user groups, trade associations, cigarette and e‐cigarette companies, think tanks, and business organizations), we located their websites and Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter accounts through Google and collected action alerts, policy statements, and messaging related to the proposed laws. We compared past (2008‐2012) and current (2013‐2015) versions of primary pro‐e‐cigarette advocacy groups’ websites using the Wayback Machine (archive.org) to access past (since 2008) web pages containing organizational descriptions, mission statements, and lists of board members and documented changes over time.

Interviews

We used archived interviews collected as part of previous research projects on state and local policymaking together with new interviews with people involved in the e‐cigarette policy debates (Table 1). Factors in selection were availability, willingness to participate, and knowledge of the subject matter. We conducted semi‐structured interviews, which allowed key informants to provide relevant information based on their perspectives. We recorded and transcribed all interviews in accordance with a protocol approved by our institution's committee on human subjects.

Table 1.

People Interviewed Regarding E‐cigarette Policy Debates

| Name | Date | Affiliation | Jurisdiction Discussed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eric Batch | August 13, 2014 | American Heart Association | Los Angeles and California |

| Todd Fraley | May 20, 2015 | Respiratory Health Association | Chicago and Illinois |

| Cynthia Hallett | July 15, 2014 | Americans for Nonsmokers' Rights | Los Angeles |

| Jim Knox | December 11, 2013 | American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network | California |

| Spencer Lyons | August 15, 2014 | American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network | Los Angeles |

| Nora Manzanilla | September 10, 2014 | Office of the Los Angeles City Attorney, Tobacco Enforcement Program | Los Angeles |

| Kendall Stagg | July 15, 2014 | Chicago Department of Public Health | Chicago |

Data Analysis

We used the available information to prepare case studies, including what types of policies were proposed, when these proposals were introduced and by whom, who was involved in the debate, and what strategies and tactics were used to pass or defeat these proposals and how they influenced the policy outcome. We established actor involvement through legislative hearing transcripts or videos (accessed online), newspaper articles, and press releases supplemented by information from interviews. We determined an actor as not participating in the policy process if we could not find publicly available data that would confirm such participation, including the interviews.

Common laws regulating e‐cigarettes deal with sales, use, taxation, licensing, marketing, and product standards.16 We assessed the strength of legislation from a public health perspective using existing tobacco control literature as well as the guidelines published by the Tobacco Control Legal Consortium25: (1) a robust enforcement measure with clear procedures put in place; (2) well‐planned implementation process; and (3) clear and broad definitions to anticipate future product innovations with clear definitions (Appendix).

Results

This analysis is organized around the different players in evolving advocacy coalitions (Table 2) and focuses on sales and smokefree legislation because in most jurisdictions studied, such laws were introduced either simultaneously or sequentially.

Table 2.

Policy Issue, Observed Interest Group Positions and Tactical Approaches Taken, and Legislative Outcome

| Policy Issue | Legislators and Other Public Health Officials | Cigarette Companies | National Voluntary Health Organizations | E‐cigarette Companies | E‐cigarette User/Retail Groups | Location Where Observed | Legislative Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E‐cigarette sales | Supported banning sales of e‐cigarettes not approved by FDA. | Opposed any ban on e‐cigarette sales. RJR reported lobbying in New York State and California.26, 27 | Did not take a position because needed more direction from federal government. | Were the largest contributors to TVECA, which opposed the measure in California. | TVECA independently opposed legislation. | New York State Illinois California | All bills failed.28, 29, 30 |

| Sales to minors | Supported prohibiting sales to minors. | Supported prohibiting sales to youth under 18 but without meaningful enforcement. | Supported legislative efforts but did not take leading role. | Supported prohibiting sales to youth under 18 but without meaningful enforcement. | Supported prohibiting sales to youth under 18 but without meaningful enforcement. | California New York State New York City | Weak youth access legislation passed in California, New York State, and New York City that nominally restricted sales to minors. |

| Defining e‐cigarettes | Supported defining e‐cigarettes as tobacco products. | Supported defining e‐cigarettes as separate from tobacco products (eg, alternative nicotine products), which would require new rulemaking and would exempt e‐cigarettes from existing tobacco control laws.18 | Opposed efforts of the cigarette companies in California not to define e‐cigarettes as tobacco products.31 | Proactively pushed legislation defining e‐cigarettes as separate from tobacco products at the state and local levels.31 | CASAA's Brad Rodu presented research on harm reduction and conservative think tank R Street Institute made statements in the media.32 | Illinois California | Illinois law defined e‐cigarettes as “alternative nicotine products” whereas in California health groups mobilized to defeat the pro‐industry definition.31, 33 |

| Sampling | Supported prohibiting e‐cigarette use in e‐cigarette retail stores. | Opposed restrictions on indoor use in retail stores. | Supported prohibiting e‐cigarette use indoors in all venues. | Opposed prohibition of e‐cigarette use in their retail stores and product restrictions on flavors to avoid adverse impact on business. | CASAA and MNVA testified at hearings,34 and CASAA urged users to Twitter bomb elected officials.35 | Duluth | Duluth was the only jurisdiction that did not provide an exemption in retail stores due to strong political leadership. |

| Sales to minors and retail licensing | Supported prohibiting sales to minors, requiring retail license, and eliminating self‐service displays. | Supported minimum age restrictions on sales to minors but opposed meaningful enforcement measures. | Supported prohibiting sales to minors and requiring retail license but opposed defining e‐cigarettes as tobacco products. | Supported minimum age restrictions on sales to minors but opposed meaningful enforcement measures. | E‐cigarette retailers testified at hearings. CASAA and SFATA mobilized users and retailers through action alerts, framing the debate on economic concerns for retailers.36, 37 | Duluth Los Angeles New York City Illinois California | Efforts led by political leadership resulted in passage of strong laws in Duluth and Los Angeles; no enforcement legislation was passed in New York City, Illinois, or California. |

| Smokefree law | Supported prohibiting e‐cigarettes wherever conventional cigarettes are prohibited. | Opposed or weakened all restrictions that included e‐cigarettes in smokefree laws. Lorillard financed a radio campaign to organize users to testify at hearings. Cigarette companies hired powerful lobbying firms to stall action on e‐cigarette proposals and to create front groups.38 Conservative think tanks and business third parties lobbied for exemptions in hospitality venues. | Opposed amending existing smokefree laws to include e‐cigarettes. | Opposed including e‐cigarettes in local smokefree ordinances. Reported lobbying in New York State and California. Framed e‐cigarette use as an individual right and restrictions as economic hardships. Created front group NYSSA to oppose restrictions in New York City. | CASAA and SFATA urged users and retailers to Twitter bomb elected officials on days of and prior to legislative hearings and used industry‐sponsored research to oppose legislation.39, 40 When legislation was inevitable, retailers, CASAA, and SFATA supported exemptions for e‐cigarette retail stores.41 | Duluth New York City Chicago Los Angeles Minnesota New York State California | Strong ordinance passed in Duluth. Failure of the ALA, AHA, and ACS to provide strong leadership and Twitter activity led to tabling ordinances and stalling action in Chicago and Los Angeles and to policymakers amending laws in New York City, Chicago, and Los Angeles to exempt theatrical performances and e‐cigarette retail stores. Minnesota passed a weak law whereas New York State and California failed to pass any law. |

Acronyms: FDA, Food and Drug Administration; RJR, R.J. Reynolds; TVECA, Tobacco Vapor Electronic Cigarette Association; CASAA, Consumer Advocates for Smoke‐free Alternatives Association; MNVA, Minnesota Vapers Advocacy Association; SFATA, Smoke‐Free Alternatives Association Trade Association; NYSSA, New Yorkers for Smarter Smoking Alternatives; ALA, American Lung Association; AHA, American Heart Association; ACS, American Cancer Society.

Legislators and Government Agencies

State legislative efforts in New York, California, and Illinois began with legislators proposing bans on the sale of e‐cigarettes that were not authorized for sale by the FDA as “appropriate for the protection of the public health,” the standard the FDA is required to use when approving new tobacco products. In 2009, the California State Legislature passed a complete sales ban, led by a legislator whose constituents were concerned about e‐cigarette sales to youth in mall kiosks,42 which was vetoed by governor Arnold Schwarzenegger.28 In 2010, New York and Illinois legislators introduced similar bills that failed to pass.29, 43

By 2013, state legislators in California (2010), New York (2012), and Illinois (2013) had shifted their focus from a complete ban on sales to prohibiting sales to youth.15, 31, 33 Most of these laws, however, lacked strong enforcement measures or penalties for noncompliant retailers18, 44 (Appendix).

Local legislative efforts originated with local health departments and politicians introducing legislation to include e‐cigarettes in existing tobacco control laws, including retail licensing and smokefree laws.

The arguments for including e‐cigarettes in existing retail licensing laws for tobacco products were centered on protecting youth. Government officials and policymakers in New York City, Chicago, and Los Angeles had a history of sponsoring tobacco control laws as far back as 1991.33, 45, 46, 47 In all 4 cities, we observed bill sponsors arguing that e‐cigarettes were being sold to minors in mall kiosks and at retail shops with close proximity to schools.45, 46, 48, 49 In 2013, schools in Los Angeles began reporting to the Los Angeles City Attorney's Office Tobacco Enforcement Program that children and teens were using e‐cigarettes in classrooms and outdoors on campus,50 including as marijuana delivery systems.51 In legislative hearings in Chicago and Los Angeles,46, 52 local health departments and legislators cited a US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report showing that youth e‐cigarette use had doubled between 2011 and 201212 as justification for government intervention to regulate e‐cigarette sales.

In order to strengthen local e‐cigarette laws the health departments of New York City, Chicago, and Los Angeles coordinated their efforts through the National Association of County and City Health Officials' Big Cities Health Coalition. The strategy was organized as a mechanism to pass legislation, with parallel implementation dates, in order to generate media interest and encourage other jurisdictions to regulate e‐cigarettes as tobacco products and to include them in existing sales and smokefree laws.53

Strong retail licensing laws were introduced in Duluth in August 2013 and in Los Angeles in October 2013 that prohibited e‐cigarette sales to minors under the age of 18, required a retailer to obtain a tobacco retail license, and eliminated sales through self‐service displays and vending machine.48, 54 Weak licensing laws were proposed in March 2013 in New York City and in September 2013 in Chicago that prohibited sales to minors under the age of 21 (New York City) and 18 (Chicago) but did not include strong enforcement provisions.

Local health department officials in New York City and Chicago (in late 2013) and in Los Angeles (in early 2014) recommended that legislators incorporate e‐cigarettes into existing tobacco control laws by amending the definition of “tobacco product” to include e‐cigarettes in order to include them in their smokefree laws.17, 54 Despite opposition from e‐cigarette and cigarette company lobbyists, third parties, and front groups, the New York City Council quickly passed its smokefree law in December 2013. Council members argued in legislative hearings that the tactics used to oppose these laws were a repeat of cigarette company strategies to prevent passage of strong public health laws.47

Shortly after Illinois state legislators passed a youth access bill that defined e‐cigarettes as “alternative nicotine products” in August 2013,55 legislators in Chicago introduced a similar proposal with an analogous definition for e‐cigarettes that would “prohibit sale of ‘alternative nicotine products’ to minors.”46 In September 2013, Mayor Rahm Emanuel and the Chicago Department of Public Health encouraged legislators to strengthen the legislation's language by changing the definition of e‐cigarettes from “alternative nicotine products” to “tobacco products” in order to include them in the city's existing tobacco retail licensing law. The Chicago Department of Public Health provided technical assistance and organized community groups to mobilize support for the proposed legislation.46 The Chicago City Council passed the ordinance in January 2014.33

National Voluntary Health Organizations

With the exception of 1 state, we did not observe any voluntary health organizations participating in state policy efforts to introduce and enact laws to ban the sale of e‐cigarettes between 2009 and 2011. By June 2011, as legislators in California, New York, and Illinois introduced legislation to regulate e‐cigarette sales and public usage, the national offices of the American Lung Association (ALA), American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network (ACS CAN), American Heart Association (AHA), and Campaign for Tobacco‐Free Kids (CTFK) started supporting laws to prohibit the sale of e‐cigarettes.56 At that time, the health voluntaries did not recommend including e‐cigarettes in existing smokefree laws and did not take a position on whether e‐cigarettes should be defined as tobacco products.57 The only state where we observed voluntary health organization activity was Minnesota, where the local voluntary health organizations advocated for a bill, enacted in March 2010, that defined e‐cigarettes as tobacco products, restricted their sales to minors, and included them in the state's retail licensing laws.19

Voluntary health organizations were clearly visible in 2 of the 4 cities we studied.31, 33 In Duluth in September 2013, the ALA organized and mobilized its grassroots network to contact elected officials through phone and written communication and recruited 13 witnesses from medical and youth groups to testify in support of the proposed sampling, sales, and smokefree laws at legislative hearings.48, 58 In New York City in December 2013, the voluntary health organizations provided testimony at a legislative hearing of the New York City Council Committee on Health, advocating for including e‐cigarettes in the city's existing smokefree law. Arguments used by voluntary health organizations in Duluth58 and New York City47 were centered on e‐cigarettes renormalizing smoking behavior and their use indoors undermining enforcement of existing smokefree laws. In New York City, with the addition of the CTFK, the voluntaries emphasized the importance of passing comprehensive public health policy to avoid social normalization, since the cigarette companies now had entered the policy debates.47, 59 Legislation to include e‐cigarettes in local smokefree air laws passed quickly (less than 2 weeks after introduction) in Duluth and New York City, where local voluntary health organizations mobilized to support the efforts of city council members.58, 60, 61

Except for the ALA, we did not observe voluntary health organizations participating in legislative efforts in Chicago and Los Angeles in 2013, when these ordinances were introduced by legislators. Instead, community groups,33, 46 medical researchers,54 and the national California‐based grassroots advocacy organization Americans for Nonsmokers’ Rights52 were primary actors in the advocacy coalition. These players testified at legislative hearings, provided technical assistance, mobilized their advocacy networks, and sent letters of support to elected officials in Chicago and Los Angeles.

E‐cigarette User Groups and Manufacturers

E‐cigarette user groups and trade associations began forming in 2008. The first group to appear in the legislative debates we studied was the e‐cigarette trade association Tobacco Vapor Electronic Cigarette Association (TVECA) in 2009. TVECA encouraged its online community of users and retailers to oppose e‐cigarette sales restrictions and to advocate for exempting e‐cigarette retail stores from existing smokefree laws.31, 62, 63

In 2009, TVECA made a public statement taking credit for a vetoed bill that was passed by the California State Legislature.64 As passed, the bill prohibited sales of e‐cigarettes not authorized by the FDA, which would have eliminated all e‐cigarette sales at the time. The bill was vetoed by Governor Schwarzenegger on the grounds that the state should “wait for the FDA.”28

By 2011, e‐cigarette user groups were publishing on their websites “calls to action” that included talking points, alerting members of efforts around the United States to restrict e‐cigarette sales and public usage, and directing users to oppose such restrictions.36,65‐67

Independent e‐cigarette retailers opposed prohibition of e‐cigarette sampling and use in retail stores and product restrictions on flavors to avoid adverse impact on business,34, 62, 63 but did not seek to permit e‐cigarette use in other venues, particularly hospitality venues.

Beginning in 2013, pro‐e‐cigarette advocacy groups began mobilizing opposition to proposed e‐cigarette sales and smokefree laws through online social media platforms, including Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.68 A common tactic we observed in Duluth, New York City, Chicago, and Los Angeles was “Twitter bombing,”69 the act of generating a trending topic on Twitter using related messaging (eg, hashtags), to overload the Twitter feeds of elected officials and to establish a false sense of consensus on a topic.70

In 2013, e‐cigarette user groups and trade associations as well as Lorillard Tobacco Company (blu eCigs, an e‐cigarette company, was acquired by Lorillard in mid‐201271) posted customized messages and Twitter hashtags opposing proposed legislation on their websites and encouraged users, including from outside the jurisdictions in which these debates were taking place, to publish and retweet these messages on Twitter and Facebook. After these Twitter bombing campaigns, legislators in Chicago and Los Angeles opposed efforts to define e‐cigarettes as tobacco products and include them in smokefree laws. In response, the authors of these bills tabled their ordinances for 1 month (Chicago) and 2 months (Los Angeles) to reorganize and mobilize public health support for their pro‐policy campaigns.46, 52 Comparable activity also took place in 2013 in Duluth34 and New York City,72, 73, 74, 75 but Twitter bombing was ineffectual because the city council leadership, executive leadership (then–Council Vice President Krug in Duluth and then‐Mayor Michael Bloomberg in New York City), and voluntary health organizations strongly supported e‐cigarette restrictions and were working to pass these ordinances quickly.

Larger independent e‐cigarette companies—NJOY, Logic (acquired by Japan Tobacco International in 2015), and V2 Cigs—appeared in policy debates beginning in 2009 and 2010.76, 77, 78, 79, 80

In 2013 and 2014, NJOY and Logic, the 2 largest independent e‐cigarette companies in the United States, spent $432,094 on lobbying in California, New York State, Los Angeles, and New York City (Table 3). In 2013, during the debates over including e‐cigarettes in existing smokefree laws and defining them as tobacco products, NJOY briefly hired a lobbyist in New York City81 and another in California.76 In New York City, Logic Technology Development hired Gotham Government Relations & Communications,38 which created New Yorkers for Smarter Smoking Alternatives (NYSSA), a vapers’ rights organization, in 2013. NYSSA organized a second letter‐writing campaign (the first was in New York City in December 201372,73,82) and circulated it online using Twitter.72 On its website and on Twitter, NYSSA urged users to request of their state legislators that they block attempts to treat e‐cigarettes as tobacco products and prohibit their use in public places.74, 75

Table 3.

Lobbying Expenditures for Cigarette and E‐cigarette Companies in New York City, Los Angeles, New York State, and California (2013 and 2014)a

| Cigarette Companies | E‐cigarette Companies | Totals | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Philip Morris | R.J. Reynolds | Lorillard | Logic | NJOY | Cigarette Companies | E‐cigarette Companies | All | |

| New York City | $712,803 | $270,815 | $36,000 | $66,000 | $500 | $1,019,618 | $66,500 | $1,086,118 |

| Los Angeles | $72,496 | $72,500 | $30,000 | $144,996 | $30,000 | $174,996 | ||

| New York State | $1,709,896 | $808,055 | $180,450 | $186,500 | $500 | $2,698,401 | $187,000 | $2,885,401 |

| California | $1,511,529 | $1,014,827 | $231,401 | $148,594 | $2,757,757 | $148,594 | $2,906,351 | |

| Total | $4,006,724 | $2,166,197 | $447,851 | $252,500 | $179,594 | $6,620,772 | $432,094 | $7,052,866 |

We present lobbying information for these 4 jurisdictions because their lobbying disclosure laws are transparent compared to those of Minnesota and Illinois. Lobbyists are required to report at the state level whether they lobby state officials, local officials, or both; only local officials were omitted.27,83

Cigarette Companies

R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company reported lobbying on e‐cigarette legislation as early as 2010 in New York State on a bill that would have prevented the sale of e‐cigarettes until approved by the FDA. We did not find any publicly available data on R.J. Reynolds’ policy position at that time.26

Beginning in 2010, at the state level in California, New York, Illinois, and Minnesota, cigarette companies lobbied to combat e‐cigarette sales restrictions and efforts to include e‐cigarettes in smokefree laws.26, 31, 84, 85, 86, 87 In 2013 and 2014, cigarette companies (led by Philip Morris USA) spent $6,620,772 on lobbying in California and New York, more than 10 times the amount ($432,094) that independent e‐cigarette companies had spent during that same time frame (see Table 3).

In 2013 in California, cigarette companies concentrated campaign contributions on political leadership, including the speaker of the California State Assembly and chair of the assembly's Committee on Governmental Organization, a committee with a history of defeating tobacco control bills.88 In New York, the Democratic Party (which dominates political leadership) began taking campaign contributions from the cigarette companies between 2011 and 2013, despite having pledged in the mid‐1990s to refuse such contributions.89 At the local level beginning in December 2013, cigarette and e‐cigarette companies used company lobbyists90 and contract lobbyists91, 92, 93 in New York City,90, 94, 95 Chicago,33 and Los Angeles96, 97, 98 to oppose e‐cigarette legislation.

Except for in New York City, where Lorillard cigarette company lobbyists testified at public hearings, cigarette companies did not testify in legislative hearings in any other jurisdiction in this study. In Los Angeles, R.J. Reynolds hired lobbyists who had previously worked on city council leadership fundraising campaigns.50, 99

The Empire State Restaurant and Tavern Association, a front group developed by the cigarette companies to oppose smokefree bars in the early 1990s,100, 101 and which shared a lobbyist with Philip Morris,102 argued in New York City against including e‐cigarettes in smokefree legislation, claiming that there would be a negative economic impact on bars.103

As noted above, in 2013 Illinois defined e‐cigarettes as “alternative nicotine products” while similar attempts made by the cigarette companies to pass this pro‐industry definition were unsuccessful in Chicago (2013) and California (2014).104 In 2014, a legislator in California introduced a bill to define e‐cigarettes as a tobacco product as part of legislation to include e‐cigarettes in the state smokefree law, but cigarette companies successfully lobbied the legislator to change the definition of e‐cigarettes to neither a “cigarette” nor a “tobacco product.”104, 105 The voluntary health organizations, which had been neutral on the bill, then successfully worked to block it.

Third Parties and Front Groups

In 2013, third‐party organizations including industry‐funded think tanks,106, 107, 108 business organizations (eg, chambers of commerce109), and hospitality associations, as well as front groups,110, 111 started opposing efforts to include e‐cigarettes in existing retail licensing and smokefree laws.

At the local level, third parties offered exemptions for indoor use in hospitality venues (restaurants, bars, and nightclubs) prior to the final Los Angeles City Council vote.47, 54, 112 None of the local governments in this study included these specific exemptions in their amended smokefree laws to incorporate e‐cigarettes. In addition to the hospitality exemption, third parties supported weak laws that would prohibit e‐cigarette sales to minors without enforcement measures or penalties for retailers. These actors also opposed retail licensing laws that would prohibit or restrict the sale of flavored products (eg, strawberry or bubblegum) on the grounds that these products assisted adults in their attempts to quit using combustible products.106

Arguments by industry‐funded think tank representatives were centered on tobacco harm reduction and e‐cigarettes as effective cessation devices.106, 113, 114, 115 They argued that including e‐cigarettes in smokefree laws would encourage relapse in smokers,106, 116, 117 and supported their stance through opinion editorials, policy studies,118 and blog posts.115, 119, 120 The Heritage Foundation and the American Council on Science and Health reposted these opinion editorials on their websites.118, 121

Additional frames used by third parties in New York City, New York State, and Los Angeles were the themes of “choice,” “freedom,” “limited government,” and “economic harm.” In New York City, industry‐funded think tanks criticized the city council for controlling personal decisions and private business,117, 119 and argued that legislation to include e‐cigarettes in smokefree laws was “hyper‐regulatory.”47 In Los Angeles, industry‐funded think tanks and the Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce framed the issue on individual liberties, personal freedoms, and unnecessary government regulation of legal products used in adult‐only venues in their unsuccessful pursuit of an exemption for bars and nightclubs.31 The California Restaurant Association also opposed including e‐cigarettes in the smokefree law in Los Angeles.

In 2014, Lorillard's blu eCigs ran a radio advertising campaign to oppose the effort to amend Los Angeles's existing smokefree law to include e‐cigarettes. The campaign urged users to attend city council hearings and testify against the ordinance,122 and blu eCigs retweeted posts, used similar hashtags to those of e‐cigarette user groups and trade associations, and encouraged its followers to retweet these messages.122

Arguing That Local and State Policymakers Should Wait for Federal Action. In 2013, cigarette companies, e‐cigarette trade associations, and third parties argued that local and state governments should delay e‐cigarette legislation until the FDA began regulating e‐cigarettes. They maintained that more research was needed from the FDA on the specific harms of e‐cigarettes before regulating their sale and use.123, 124, 125 The FDA argument was used in Chicago126, 127 and Los Angeles54 by legislators to oppose including e‐cigarettes in smokefree laws. By the end of 2014, Illinois and California had not passed legislation that included e‐cigarettes in retail licensing and smokefree laws.31, 33

Discussion

Two advocacy coalitions evolved to influence e‐cigarette policy adoption at the state and local levels. The first consisted of public health officials, school administrators, some legislators, and, by 2014, the voluntary health organizations, which supported policies to minimize youth initiation and use by treating e‐cigarettes like other tobacco products. The second initially comprised loose‐knit e‐cigarette user groups, retailers, and independent e‐cigarette companies, and then, after 2013, cigarette companies, third parties, and front groups became involved. This pro‐e‐cigarette advocacy coalition sought to avoid regulation that could adversely impact business by opposing strong sales, usage, and taxation laws. The one difference in state and local priorities between the original pro‐e‐cigarette interest groups and the cigarette companies and their allies was that the former was not concerned with whether e‐cigarette use was restricted in hospitality venues, while the latter opposed such restriction.

The changing engagement of the voluntary health organizations and cigarette companies affected the dynamics of policy adoption. In 2013, local legislation in Duluth and New York City passed swiftly when local chapters of the voluntary health organizations mobilized to support the efforts of city council members. In 2014, legislation in Chicago and Los Angeles passed with more difficulty, compared to Duluth and New York City, because voluntary health organizations were slow to support elected officials and their efforts to include e‐cigarettes in existing sales and smokefree laws for tobacco products.

Despite their initial reluctance to enter the debate, the larger voluntary health organizations were much quicker to join the e‐cigarette policy debate together with legislators, health officials, and school administrators than they were during the smokefree debates for conventional cigarettes in the 1970s and 1980s. This more rapid engagement may have contributed to e‐cigarette legislation passing more quickly than comparable restrictions on secondhand smoke. For example, whereas it took 20 years for local and state governments to pass 400 laws restricting smoking (many of which were not comprehensive and only required separate smoking sections in workplaces and restaurants128), it took only about 6 1/2 years to pass the same number of laws to include e‐cigarettes in smokefree provisions (January 2009‐October 2015).

In the states included in this study, legislation was either weakened or defeated after the cigarette companies entered the policy debates. Minnesota passed a weak smokefree law that only prohibited e‐cigarette use in government buildings and schools. Campaign contributions and lobbying have been associated with influencing political voting behavior on tobacco policies at the state and federal level.129 Similar activity by cigarette companies and front groups likely contributed to New York State's failure to include e‐cigarettes in existing smokefree laws. In 2016 the California Legislature enacted legislation that added e‐cigarettes to the state clean indoor air and retailer licensing laws. This legislation, which passed in a special legislative session on health, was strongly supported by the voluntary health agencies and opposed by the major cigarette companies as well as the pro‐e‐cigarette advocacy network. The fact that it was a special session allowed the legislation to bypass the Assembly committee that defeats most tobacco control legislation. In Illinois, the cigarette companies were successful in passing a pro‐industry definition that labeled e‐cigarettes as “alternative nicotine products.”

Cigarette company lobbyists are deeply entrenched in state legislatures and are used to pressure legislators behind the scenes to weaken or defeat proposed tobacco control laws.129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134 A similar situation was repeated in the e‐cigarette policy debates after the cigarette companies entered the market. While independent e‐cigarette companies hired contract lobbyists and gave political contributions to elected officials, their contributions were a fraction of what cigarette companies had given.

By the time e‐cigarette legislation was being considered, policymakers and the public had developed knowledge about and mistrust in the cigarette companies.135, 136 This situation, coupled with public concerns on rising youth e‐cigarette use, may have served as a catalyst for quick passage of e‐cigarette legislation at the local level.

The Pro‐e‐cigarette Advocacy Network

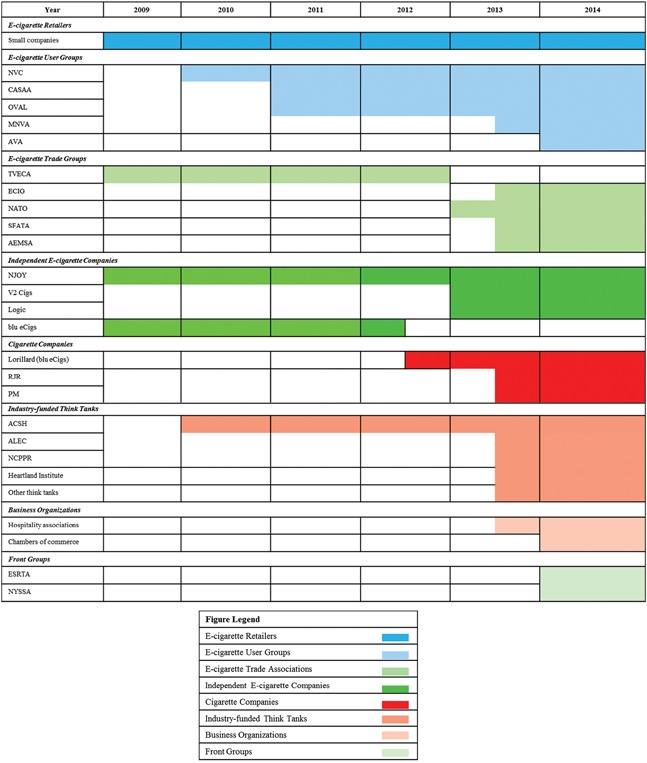

Pro‐e‐cigarette advocacy began as loose‐knit grassroots efforts from retailers, local users, and independent e‐cigarette companies, which were generally hostile toward the established cigarette companies (Figure 1). The initial pro‐e‐cigarette advocates were separate, in terms of both the e‐cigarette business and the advocacy network, from the cigarette companies.76, 137, 138, 139 By the end of 2013, national e‐cigarette companies were using similar tactics to those of cigarette companies, such as lobbying state legislators behind the scenes and using front groups to disseminate their policy positions. Unlike cigarette companies, which have no public credibility,100, 130, 135, 136 the large e‐cigarette companies provided a more credible business image and were sometimes publicly present at legislative hearings to debate whether or not to include e‐cigarettes in retail licensing and smokefree laws (New York City and California). By 2014, actors in the pro‐e‐cigarette advocacy network had become more intertwined, including the cigarette companies (Table 4).

Figure 1.

The Pro‐e‐cigarette Advocacy Network, 2009‐2014

The pro‐e‐cigarette advocacy network began in 2009 as loose‐knit grassroots efforts dominated by small‐scale e‐cigarette retailers, e‐cigarette user groups, and independent e‐cigarette companies, but quickly transformed as cigarette companies entered the market and third parties began promoting e‐cigarettes. By the end of 2014, the network had evolved into an aggressive, well‐coordinated, and sophisticated campaign.31, 40, 47, 118, 119, 124, 125, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154 We refer to the National Vapers Club as “NVC,” Consumer Advocates for Smoke‐free Alternatives Association as “CASAA,” Oklahoma Vapers Advocacy League as “OVAL,” Minnesota Vapers Advocacy as “MNVA,” American Vaping Association as “AVA,” Tobacco Vapor Electronic Cigarette Association as “TVECA,” Electronic Cigarette Industry Group as “ECIG,” National Association of Tobacco Outlets as “NATO,” Smoke‐Free Alternatives Trade Association as “SFATA,” American E‐Liquid Manufacturing Standards Association as “AEMSA,” R.J. Reynolds as “RJR,” Philip Morris as “PM,” American Council on Science and Health as “ACSH,” American Legislative Exchange Council as “ALEC,” National Center for Public Policy Research as “NCPPR,” Empire State Restaurant and Tavern Association as “ESRTA,” and New Yorkers for Smarter Smoking Alternatives as “NYSSA.”

Table 4.

Organizations Involved in the Pro‐e‐cigarette Advocacy Network

| Organization | Description of Organization |

|---|---|

| E‐cigarette Retailers | |

| Independent Vapor Retailers of Minnesota | A nonprofit group that was formed to help fight for the rights and regulations of the independent business owners and entrepreneurs that comprise the vapor retail business in Minnesota.155 |

| E‐cigarette User Groups | |

| Primary Groups | |

| Consumer Advocates for Smoke‐free Alternatives Association (CASAA) | An e‐cigarette “grassroots” user group established in 2009 to defeat restrictions on e‐cigarettes, including “tobacco, e‐cigarette or even smoking state law[s].”156 CASAA mobilized its members through its Constant Contact program, which provides members with newsletters and action alerts on proposed e‐cigarette legislation in their state and locality. Two of its members, Brad Rodu and Carl V. Phillips, received funding from British American Tobacco, US Smokeless Tobacco Company (UST), PM, RJR, and Swedish Match to conduct research on smokeless tobacco and harm reduction. One member, Greg Conley, is a senior fellow at the Heartland Institute and president of the AVA. CASAA framed opposition to e‐cigarette restrictions on cigarette company arguments, including “no health risks” and “wait for the FDA.”157, 158, 159, 160, 161 One of its members attended the Global Tobacco & Nicotine Forum (GTNF) in 2014. |

| National Vapers Club (NVC) | A “consumer‐based” e‐cigarette user group (formerly known as the Long Island Vapers Club) that was founded in 2009 by the 2014 SFATA co‐chair, Spike Babaian. In 2009, its website message was “Meeting Place for lovers of e‐cigarettes, personal vaporizers and all things ‘fog’ producing!”162 In 2010 the message changed to “It's Not Smoke, It's Vapor! Make the Switch Today!”141 and in 2013, it changed to “Protect your right to vape!” “Help us fight for vapers’ rights!” and “NVC provides written testimony all over the country.”64 NVC opposed e‐cigarette regulation in New York City and New York State163; funded e‐cigarette research claiming secondhand e‐cigarette emissions pose no apparent risk to human health164; and framed opposition to e‐cigarette restrictions on e‐cigarette company arguments, including “individual freedom, personal liberties, choice,” “discriminatory,” and “no health risks.”65 |

| Secondary Groups | |

| Minnesota Vapers Advocacy (MNVA) | An e‐cigarette user group from Minnesota established in September 2013 in response to the Duluth City Council's move to restrict the sales, usage, and sampling of e‐cigarettes. MNVA supports “common sense regulations” such as restricting sales to minors and voluntary business policies for indoor usage but opposes excessive government regulation of the sale and use of e‐cigarettes.165 |

| Oklahoma Vapers Advocacy League (OVAL) | An organization founded in 2012 by local e‐cigarette store owners to protect consumer “rights” to reduced‐harm alternatives to tobacco, “while assisting in proper legislation that affords consumers the right of choice.”142 |

| E‐cigarette Trade Associations | |

| Primary Groups | |

| American Vaping Association (AVA) | An industry‐funded consumer e‐cigarette advocacy group166 founded in 2013 and located in New Jersey.167 Its president, Greg Conley, is a senior fellow at the Heartland Institute and a member of CASAA. The AVA opposed efforts to include e‐cigarettes in smokefree laws in California, New York, and Minnesota, and while it did not exist at the time that the cities in our analysis were debating policy, Conley did oppose these local efforts.47, 168 |

| Electronic Cigarette Industry Group (ECIG) | An organization composed of consumers, manufacturers, importers, and distributors of e‐cigarettes that “supports strengthening regulations to keep e‐cigarettes out of the hands of children.”169 |

| National Association of Tobacco Outlets (NATO) | A national trade organization that was established to “enhance the common business interests of all tobacco retailers.” In 2006, NATO and the Heartland Institute ran a campaign to “change public opinion about tobacco” by organizing to prevent restrictions on public smoking.170 NATO's executive director worked closely with the Tobacco Institute (TI) in the 1980s and 1990s.132 In 2013 and 2014, NATO provided written testimony to the Los Angeles City Council and the New York State Legislature opposing restrictions on e‐cigarette sales and public usage. It framed arguments against e‐cigarette restrictions on “no health risks” and “wait for FDA.”47, 125 |

| Smoke‐Free Alternatives Trade Association (SFATA) | A membership‐based industry trade organization composed of e‐cigarette distributors, manufacturers, wholesalers, retailers, and consumers. SFATA membership included a monthly newsletter, a daily newsfeed, the opportunity to serve on SFATA committees, and exclusive members‐only content. Two of its board members previously worked with the TI and PM. SFATA supports policies that restrict sales to youth and launched its Age to Vape program in 2015 to “require retailers to display signs indicating they do not sell vapor products to minors and to check customer ID before making a sale.”171 SFATA used cigarette company arguments to oppose restrictions, including “individual freedom, personal liberties, choice,” “government intrusion,” “discriminatory,” “economic,” “no health risks,” and “wait for FDA.”37, 40, 172, 173 |

| Tobacco Vapor Electronic Cigarette Association (TVECA) | An international nonprofit e‐cigarette trade association dedicated to a “sensible and responsible” e‐cigarette market. Formed in 2008 as Electronic Cigarette Association (became TVECA in 2011), TVECA began opposing state proposals to prohibit sales of e‐cigarettes not approved by the FDA.143 In 2012, it criticized SFATA and V2 Cigs (an e‐cigarette company) for touting that e‐cigarettes were smoking cessation devices.174 |

| Secondary Groups | |

| American E‐Liquid Manufacturing Standards Association (AEMSA) | An e‐cigarette manufacturers trade association dedicated to “creating responsible and sustainable standards for the safe manufacturing of ‘e‐liquids’ used in e‐cigarettes.”175 Konstantinos Farsalinos is AEMSA's medical consultant. Farsalinos's research was funded by e‐cigarette companies, and he was an external reviewer for 2 Lorillard 2014 studies that provided favorable results for the e‐cigarette business.176 In 2014, AEMSA participated in the Tobacco Merchants Association's 99th Annual Meeting and Conference with 2 other e‐cigarette trade associations, 2 large e‐cigarette companies, 2 major cigarette companies, and 2 industry‐funded think tanks.177 |

| California Distributors Association (CDA) | An organization originally formed as the California Association of Tobacco and Candy Distributors, the CDA has long opposed tobacco legislation in California.178 In 2010, the CDA reported lobbying on e‐cigarette legislation at the state level in California.31 |

| Independent E‐cigarette Companies | |

| Logic Technology Development | The second largest independent e‐cigarette company (NJOY being the largest) founded in Livingston, New Jersey, in 2010. Its president was a former PM executive.179 Logic Technology Development opposed efforts in New York City, New York State, and Los Angeles to restrict the usage of e‐cigarettes in 2013 and 2014.180 It framed opposition to e‐cigarette restrictions on cigarette company arguments, including “individual freedom, personal liberty, choice,” “government intrusion,” “no health risks,” and “wait for FDA.”47 |

| NJOY | The largest independent e‐cigarette company on the US market with a mission to “obsolete cigarettes.”181 In 2009, NJOY hired the scientific consulting firm Exponent (formerly Failure Analysis Associates), a company that began producing paid research questioning the health effects of secondhand smoke exposure for cigarette companies as early as 1986.182, 183, 184 Three members of NJOY's executive leadership were previously employed with PM.185, 186 NJOY was paid to become a member of ALEC in June 2013187 and opposed New York City, Chicago, and Los Angeles public usage ordinances in 2013 and 2014 on the grounds that restrictions deter smokers from switching to e‐cigarettes. One of its members was a lobbyist for UST in Illinois.188 It framed opposition to e‐cigarette restrictions on cigarette company arguments “no health risks” and “wait for the FDA.”47, 54, 189 |

| V2 Cigs | An e‐cigarette company of VMR Products, founded in 2009. NATO and SFATA are partners. One person on its executive management team was formerly employed with RJR for 15 years.190 Its founder sits on the board of SFATA and has held the roles of president and treasurer of the board.191 |

| Cigarette Companies | |

| Altria/Philip Morris (PM) | A cigarette company with a long history, PM developed e‐cigarette company MarkTen, which entered the US market in August 2013.192 In 2015, PM promoted lengthy health warning labels193 that were ironically much stricter than the warnings required for its own conventional cigarettes. Small e‐cigarette companies complained that these requirements would benefit larger companies. In 2003, PM changed the name of its parent company to Altria to improve its corporate image. We identify Altria as PM to unmask the cigarette company's attempts to hide behind a more “neutral corporate name.”194 PM framed opposition to e‐cigarette restrictions on “reduced harm” and “wait for FDA” arguments.123, 195 PM attended the GTNF in 2014. |

| Lorillard (blu eCigs) | A cigarette company that in 2012 acquired blu eCigs, an e‐cigarette company created in 2009. As of March 2015, blu eCigs controlled 50% of the retail market share.196 It framed opposition to e‐cigarette restrictions on “individual freedom, personal liberties, choice,” “unnecessary government regulation,” “discriminatory,” “no health risks,” “unreasonable,” and “wait for the FDA.”41, 47, 122, 144 |

| RAI Services Company/R.J. Reynolds (RJR) | A cigarette company that entered the US e‐cigarette market in July 2013 with its Vuse E‐Cigarettes,197 RJR petitioned the FDA to ban the production and distribution of second and third generation e‐cigarettes (vape pens and advanced personal vaporizers, respectively). As of August 2015 RJR only produced first generation “cigalike” e‐cigarettes and would thus escape such regulation.198 RJR attended the GTNF in 2014. |

| Industry‐Funded Think Tanks | |

| Primary Groups | |

| American Council on Science and Health (ACSH) | An organization founded in 1978, ACSH claims to be a “consumer health education and advocacy organization” that disseminates its “research” to the public, media, and policymakers. Industry‐funded ACSH frequently defends cigarette companies from smokefree science produced by government and academia. ACSH received funding from PM and RJR as late as 2013.108 It began opposing federal government regulation of e‐cigarettes in 2010.199 Its former assistant executive director, Jeff Stier, was employed with NCPPR as of May 2016. ACSH opposed New York City and Los Angeles public usage laws in 2013 and 2014 and framed opposition to e‐cigarette restrictions on cigarette company arguments, including “government intrusion” and “no health risks.”47, 113 |

| Heartland Institute | An organization founded in 1984 whose mission is to “discover, develop, and promote free‐market solutions to social and economic problems.”200 Between 1991 and 2001, PM provided $400,000 to the Heartland Institute in exchange for its opposition to tobacco control measures.69, 201, 202, 203, 204 One of the Heartland Institute's former board members (Roy Marden) simultaneously served as manager of industry affairs at PM in the 2000s.205 The Heartland Institute continues to deny the science on secondhand smoke as a health hazard. In 2014,145 the Heartland Institute began advocating for smokers to switch to less harmful e‐cigarettes. In 2014, Greg Conley of AVA and CASAA and Jeff Stier, a representative for the NCPPR, began working with the Heartland Institute.206 Representatives of the Heartland Institute framed opposition on cigarette company arguments, including “individual freedom, personal liberties, choice,” “no health risks,” and “unreasonable.”31, 117, 118, 119, 207, 208, 209 |

| National Center for Public Policy Research (NCPPR) | A Tea Party–related communication and research foundation135 advocating for a “strong national defense and dedicated to providing free market solutions to today's public policy problems.”210 PM financed at least $165,000 for its activities between 1991 and 2001.135 In December 2013, NCPPR began opposing e‐cigarette sales, usage, and taxation legislation. One of its members was formerly employed with ACSH and, as of April 2015, serves as a policy advisor for the Heartland Institute. NCPPR framed opposition to e‐cigarette restrictions on cigarette company arguments, including “individual freedom, personal liberties, choice,” “no health risks,” and “unreasonable.”31, 117, 118, 119, 207, 208, 209 It attended the 2014 GTNF with CASAA's Carl V. Phillips, SFATA's Phil Daman and Ron Tully, and 6 major tobacco companies. |

| Secondary Groups | |

| American Enterprise Institute (AEI) | The longest‐standing industry‐funded think tank in this analysis, AEI was established in 1943 as an organization dedicated to an unrestricted free market. In 1980, the cigarette companies paid AEI to conduct a cost‐benefit analysis of smoking restrictions to counter the social cost argument developed by health advocates.211 Between 1991 and 2001 PM funded its activities.30 One of its members sat on the advisory board of CASAA and presented at the 2015 ALEC annual meeting on how e‐cigarette users inhale a combination of water vapor and nicotine. |

| American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) | An industry‐funded organization that works to advance “limited government, free markets and federalism at the state level”212 by pushing model legislation on a wide variety of issues. ALEC's funding sources are primarily (98%) from corporations and corporate foundations.213 Since 1978, ALEC has supported pro‐cigarette positions, including opposing FDA regulation of tobacco, promoting industry‐sponsored youth smoking prevention programs, and adopting PM's proactive efforts to pass preemption and accommodation legislation as model legislation.214 Members and funders include Lorillard, PM, RJR, the Smokeless Tobacco Council, and the Cigar Association of America. In June 2013, NJOY joined ALEC's Commerce, Insurance and Economic Development and Tax and Fiscal Policy Task Forces187; the following year, at ALEC's 2014 Spring Task Force Summit and 2014 States and Nation Policy Summit, ALEC presented on “Regulating Electronic Cigarettes: Jeffersonian Style”215 and “Vapor Usage Restrictions.”216 |

| Americans for Tax Reform (ATR) | An organization founded in 1985 by Grover Norquist, ATR “opposes all tax increases as a matter of principle.” ATR has historic ties to the cigarette companies and was funded by PM in 1999 ($435,000) and 2000 ($100,000)217 in exchange for its opposition to state cigarette taxes.132 Between 1991 and 2001, ATR received $1,385,000 from PM in exchange for press releases, letters to Congress, media outreach, and position papers. It opposed Duluth's public usage ordinance, cited a study funded by CASAA to argue against treating e‐cigarettes as tobacco products, and framed opposition on the cigarette company arguments, including “government intrusion” and “no health risks.” |

| R Street Institute | An industry‐funded organization that promotes free markets and limited and effective government with offices in DC, Florida, Texas, California, Alabama, and Ohio. The R Street Institute is an associated member of SPN, which pushes model legislation from ALEC.218 One of its members is a senior fellow at the Heartland Institute. Prior to 2012, the R Street Institute was the Heartland Institute's DC branch funded by insurance companies but became independent after the Heartland Institute in Chicago compared terrorists to proponents of climate change.208 The R Street Institute opposed Duluth's 3 ordinances for e‐cigarettes in September 2013118 and framed opposition on the cigarette company argument “no health risks.” |

| State Policy Network (SPN) | An industry‐funded think tank network that promotes limited government and market‐friendly public policies at the state and local level. In September 2013, SPN's annual meeting was funded by NJOY, PM, RJR, ALEC, ATR, and the R Street Institute.219 In 2010, PM and RJR contributed $105,000; major cigarette companies have funded SPN since the early 1990s in exchange for opposition to smokefree laws and cigarette taxes.220 |

| Business Organizations | |

| California Restaurant Association (CRA) | A California‐based organization that advocates for local, state, and national policy issues on behalf of restaurateurs to create a business‐friendly environment in California. CRA opposed Los Angeles e‐cigarette public usage ordinance in March 2014 on the grounds that there was not enough scientific evidence to justify a “ban” on using e‐cigarettes. In 1992, the CRA opposed the Los Angeles effort to restrict smoking in restaurants,221 while also receiving money from PM ($2,000)222 and the TI ($250) to fund its activities. Historically, the CRA had opposed smoking restrictions at the local level223 but in 1993 began to support the proposed statewide smokefree legislation AB13, which passed in 1994.224 It framed arguments on “no health risks” and “wait for the FDA.” |

| Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce | A longtime cigarette companies' third‐party ally225 that opposed the e‐cigarette public usage ordinance in Los Angeles. RJR was a gold member,226 which for a $5,000 annual membership fee provided the cigarette company with “direct access to Chamber public policy counsel.”109 The chamber attempted to exempt bars and nightclubs from the proposed smokefree law in Los Angeles in 2014 and framed arguments against e‐cigarette restrictions on the cigarette company argument “individual liberties, personal freedoms, choice.”227 |

| National Association of Convenience Stores | A longtime cigarette company third party that opposes tobacco control measures. Statewide associations, which are organized by the national association, opposed e‐cigarette sales and usage restrictions in New York.228 |

| New York City Hospitality Alliance | A broad‐based membership association founded in 2012 to represent the interests of restaurants, bars, lounges, destination hotels, and major industry suppliers.229 The alliance opposed New York City public usage law in 2013 and argued for exemptions in restaurants and bars.47 |

| Front Groups | |

| Empire State Restaurant and Tavern Association (ESRTA) | A cigarette company third party created in 1987 in New York City to promote the cigarette companies’ accommodation program.100 Throughout the years ESRTA fought against local smoking restrictions, pushed preemption, promoted erroneous economic impact studies, and filed a lawsuit against New York State to prevent implementation of its law in 1995. The TI contributed at least $400,000 for the group's assistance in fighting any restrictions on smoking.230, 231 It has also been known as the United Restaurant, Hotel and Tavern Association and the New York Tavern and Restaurant Association. In 2014, ESRTA testified in opposition to e‐cigarette restrictions in New York State,103 citing adverse “economic” impact on bars and restaurants, and argued for policymakers to “wait for FDA” regulation of e‐cigarettes. |

| New Yorkers for Smarter Smoking Alternatives (NYSSA) | An e‐cigarette company front group founded in 2013 by David Schwartz,232 lobbyist for Gotham Government Relations & Communications, which represents Logic Technology Development. NYSSA alleges to be a coalition composed of local retailers, wholesalers and distributors, and members of the public to fight against local and state attempts to restrict sales and public usage of e‐cigarettes.233 It framed arguments against e‐cigarette restrictions on cigarette company arguments, including “unnecessary government regulation,” “irrational/extreme policy,” and “no health risks.”234 |

Within some of the categories we distinguish between “primary” and “secondary” groups; “primary” indicates that the organizations were active in at least 3 of the 8 jurisdictions we examined.

This situation was in direct contrast to the top‐down advocacy network the cigarette companies organized to combat tobacco control laws beginning in the 1970s.100, 130, 131, 132, 134, 135, 211, 235, 236, 237, 238, 239

As in the 1960s and 1970s, when some public health authorities were supporting tobacco industry efforts to make a “safe cigarette,”240 some public health experts expressed optimism toward e‐cigarettes,6, 7, 50, 241, 242 considering their worth for harm reduction. The most prominent argument against e‐cigarette regulation in 6 of the 8 jurisdictions studied was that e‐cigarettes were less harmful than conventional cigarettes because they delivered lower doses of many of the toxins in cigarette smoke and consequently did not warrant the same restrictions.

The debate over the value of e‐cigarettes for harm reduction within the public health community facilitated arguments from e‐cigarette and cigarette companies243 on how certain regulations on e‐cigarettes would be detrimental to public health. Later, after the cigarette companies entered the e‐cigarette market, these arguments were widely circulated by industry‐funded think tanks106, 113, 117, 118, 119, 140, 207, 244, 245, 246, 247, 248, 249 and front groups234, 250 in the media.106, 113, 114, 115, 244, 251, 252, 253, 254, 255, 256

In addition to using think tanks and front groups to disseminate their argument, cigarette companies engaged in many other activities that were similar to those they had undertaken since the tobacco control debates beginning in the 1970s.

Messaging Similar to Smokefree Debates From the 1970s Through the 1990s

The cigarette companies have a record of using “imminent” federal regulation as an argument against local and state smoking restrictions while simultaneously fighting the proposed federal regulations. In 1994, the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) proposed an indoor air quality regulation to mandate workplace smoking restrictions with the option of creating separate smoking spaces and ventilation systems.237, 257 At the same time, local and state governments were considering stronger restrictions on smoking in public places (usually 100% smokefree). The cigarette companies successfully argued in some jurisdictions that local action was unnecessary because federal action was imminent and that any local or state law passed would be preempted by the OSHA rule.237, 257 Even before April 2014, when the FDA issued its proposed “deeming” rule to extend its authority to regulate the manufacture, marketing, sale, and distribution of tobacco products to e‐cigarettes,10 cigarette and e‐cigarette companies, e‐cigarette user groups, trade associations, retailers, and think tanks argued in legislative hearings that local and state governments should postpone legislation and wait for the pending FDA regulation.123, 125, 195, 258, 259 More importantly, even though the FDA has asserted jurisdiction over e‐cigarettes, the agency does not have jurisdiction over tobacco retail sales and licensing, smokefree laws, or taxation—the subjects of state and local legislation.

Supporting Nominal Tobacco Control Laws to Enact Pro‐industry Legislation for E‐cigarettes

The cigarette companies have long pursued passage of weak sales‐to‐youth laws to displace effective tobacco control interventions.260, 261 For example, in 1992 after Congress passed the Synar Amendment, which required states to document reductions in youth access to tobacco products in order to maintain their federal substance abuse prevention and treatment block grants,262 the cigarette companies used Synar's requirement to convince state legislatures to pass nominal age‐restriction laws that omitted meaningful enforcement and included preemptive language to block localities from enacting stronger laws.261, 263 Similarly, for e‐cigarettes, cigarette companies used nominal youth access laws to attempt to pass laws including pro‐industry definitions separating e‐cigarettes from tobacco products.18 By May 2016, at least 19 states had passed youth access laws that defined e‐cigarettes as separate from tobacco products, using model legislation from R.J. Reynolds.201

Creating and Mobilizing Grassroots Networks

Grassroots efforts encouraging contact with legislators have substantial influence on legislative voting behavior.69 For e‐cigarette advocacy, social media was used to support and oppose restrictions on e‐cigarettes,68 particularly whether to include them in smokefree laws.31, 69, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 82, 264 NYSSA's letter writing campaign on Twitter in New York and Lorillard's social media campaign in Los Angeles are examples of e‐cigarette and cigarette companies utilizing new technology to mobilize against e‐cigarette restrictions. Because social media accounts can be created without public disclosure to policymakers, the pro‐e‐cigarette advocacy network will likely continue to use social media (eg, Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram) as tools to mask their involvement in these debates.

While we did not identify any financial links between the cigarette companies and the original and current e‐cigarette advocacy groups, after the cigarette companies entered the e‐cigarette market and policy debates, they were able to utilize the presence of existing grassroots networks to lobby state legislators behind the scenes, where they had more influence over the policymaking process.129, 265, 266 This situation differed from the 1970s, when the cigarette companies created top‐down advocacy networks, beginning with the Tobacco Action Network,235 which consisted of people working in the industry, and “independent” smokers’ rights groups to generate the appearance of popular opposition to smoking restrictions.130, 131, 134, 135, 211, 267, 268, 269

Limitations

The e‐cigarette policymaking environment was rapidly changing and new laws were emerging during the completion of this article. Our analysis of actor involvement in the e‐cigarette debates was limited to publicly available data, for which lobbyist disclosure and reporting laws in some states do not require that lobbyists report lobbying expenditures or, as in Illinois and Minnesota, mandate that companies disclose the amounts paid to their direct or contract lobbyists.270 Additionally, cigarette company lobbyists are not required to report whether they lobbied legislators on cigarette or e‐cigarette regulations, which makes it difficult to determine the influence that the cigarette companies, including third‐party allies, had over proposed legislation. It is also difficult to uncover the funding sources of the think tanks involved in these debates (including the Heartland Institute, the National Center for Public Policy Research, and the American Council on Science and Health) because federal law does not require such 501(c)(3) organizations to reveal their corporate sponsors. In the absence of accessible public information, organizations dedicated to demanding corporate accountability are playing important roles in the online publication of leaked reports and financial plans disclosing cigarette company sponsorship of third parties, many of which were involved in the e‐cigarette policy debates we examined.106, 107, 108, 111, 201

Conclusion

The 2 coalitions that emerged in the state and local e‐cigarette policy debates studied in this analysis evolved over time, after the major voluntary health organizations and cigarette companies joined the debates.

The voluntary health organizations missed an opportunity to help implement strong state‐level legislation before the major cigarette companies entered the debate. By 2014, the e‐cigarette policy debates had evolved into 2 advocacy coalitions, which had come to resemble the advocacy coalitions of early tobacco control debates, those that supported regulation and those that opposed regulation, with health departments and voluntary health organizations on one side and cigarette companies and e‐cigarette companies on the other. As in the earlier debates over tobacco control policy beginning in the 1970s, in the 21st century, state legislators were slower than local governments to adopt strong legislation due to intense cigarette company lobbying at the state level without countervailing pressure from the voluntary health organizations. At the local level, where policymakers were more responsive to the concerns of their constituents than to those of corporate lobbyists, e‐cigarette policymaking continued to accelerate even after the cigarette companies entered into these debates. While state legislation is possible, as with earlier tobacco control debates, local governments present a viable option for policymakers and health advocates to overcome cigarette company interference in the policymaking process.

Funding/Support

This project was supported in part by National Cancer Institute grant CA‐060121and UCSF funds from the FAMRI William Cahan Endowment Fund and Dr. Glantz's Truth Initiative Distinguished Professorship. The funding agencies played no role in the selection of the research question, conduct of the research, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. No disclosures were reported.

Acknowledgements: None.

Appendix. Summary of Proposed and Enacted Local and State E‐cigarette Regulations in California, New York, Minnesota, and Illinois, 2009‐2014

| Date | Location | Policy Issue | Regulation | Language as Introduced | Last Action | Changes Made Strengthened or Weakened |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 Sept 2009 | California | Sales | Amends law to include devices that deliver doses of inhaled nicotine through a vaporized solution42 | SB400 to prohibit sales of electronic cigarettes not approved by the FDA | Governor veto, 10 Nov 2009 | No change |

| 12 Jan 2010 | New York State | Sales | Amends law to include e‐cigarettes as battery‐operated devices that deliver nicotine43 | A9529 to prohibit the sale of e‐cigarettes not approved by the FDA and prohibit sales to minors | Failed, 21 April 2010 | No change |

| 14 Jan 2010 | California | Sales | Amends law to include tobacco substitutes that deliver doses of inhaled nicotine through a vaporized solution271 | SB882 to prohibit sale of e‐cigarettes that had not been approved by the FDA to minors and establishes infractions for violating this prohibition | 27 Sept 2010 | Language removed for penalties for retailers by the California State Assembly Committee on Governmental Organization |

| 8 Mar 2010 | Minnesota | Sales | Amends definition of tobacco products to include e‐cigarettes19 | HF677 to prohibit e‐cigarette sales to minors and defines e‐cigarettes as any product containing, made, or derived from tobacco that is intended for human consumption, whether chewed, smoked, absorbed, dissolved, inhaled, snorted, sniffed, or ingested by any other means, or any component, part, or accessory of a tobacco product | 11 May 2010 | No change |

| 2 Sept 2010 | Illinois | Sales | Amends tobacco accessories law to include nicotine delivery products272 | SB3174 to prohibit sale of nicotine products not approved by the FDA | Died, 21 Jan 2011 | Language removed permitting sale of “modified risk product” |

| 15 Feb 2012 | New York State | Sales | Amends tobacco product distribution law to include e‐cigarettes in definition of prohibited sales to minors273 | A09044B to prohibit the sale of e‐cigarettes to minors | 5 Sept 2012 | No change |

| 15 Feb 2013 | Illinois | Sales | Amends definition of tobacco products to include e‐cigarettes and prohibits sales to youth274 | HB2250 to prohibit the sale of e‐cigarettes to minors | Died, 4 Dec 2014 | Senate removed e‐cigarettes from the definition of tobacco products and defined alternative nicotine products; no further action taken as Illinois passed Senate version of bill |

| 15 Feb 2013 | Illinois | Sales | Prohibits sales and distribution of alternative nicotine products to minors55 | SB1756 to prohibit the sale of “alternative nicotine products” to minors | 15 Aug 2013 | No change |

| 22 Feb 2013 | California | SF | Amends clean indoor air law to include e‐cigarettes in definition of tobacco product104 | SB648 to prohibit e‐cigarette use wherever conventional cigarettes are prohibited | Died, 2 July 2014 | Defined e‐cigarettes as devices that provide an inhalable dose of nicotine by delivering a vaporized solution; removed any restrictions on where e‐cigarettes were used or advertised and merely restricted the sale of e‐cigarettes in vending machines unless the vending machines were in adult‐only venues that are permitted to sell alcohol |

| 20 Mar 2013 | New York City | Sales | Amends youth access law to prohibit sales to minors and young adults275 | Local law 94 to prohibit sales of cigarettes and tobacco products to individuals under 21 years of age | 22 Nov 2013 | Law strengthened to include e‐cigarettes in the definition of tobacco product, and restricts their sale to individuals under 21 years of age |

| 15 Aug 2013 | Duluth | Sampling | Amends law to prohibit indoor use of e‐cigarettes in any establishment with a tobacco retail license48 | Ord. 13‐058‐O to prohibit sampling of e‐cigarettes in tobacco and e‐cigarette retail stores | 9 Sept 2013 | No change |

| 15 Aug 2013 | Duluth | SF | Amends definition of smoking to include e‐cigarettes48 | Ord. 13‐059‐O to prohibit e‐cigarette use in public places, workplaces, bars, restaurants, outdoor dining and bars areas, and within 15 feet of entrances | 9 Sept 2013 | No change |

| 15 Aug 2013 | Duluth | TRL | Amends definition of tobacco product to include electronic smoking devices (e‐cigarettes, e‐hookahs, e‐cigars, e‐pipes)48 | Ord. 13‐060‐O to prohibit sales to minors, require a tobacco retail license, prohibit vending machine sales | 9 Sept 2013 | No change |