Abstract

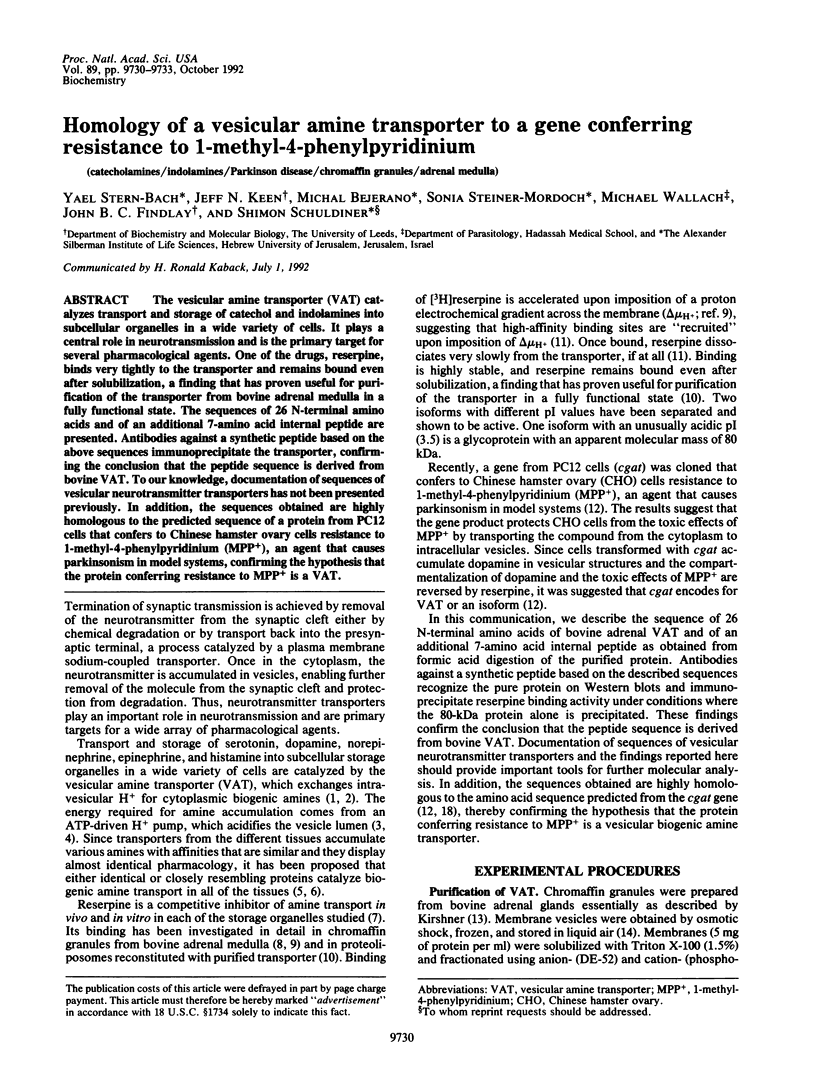

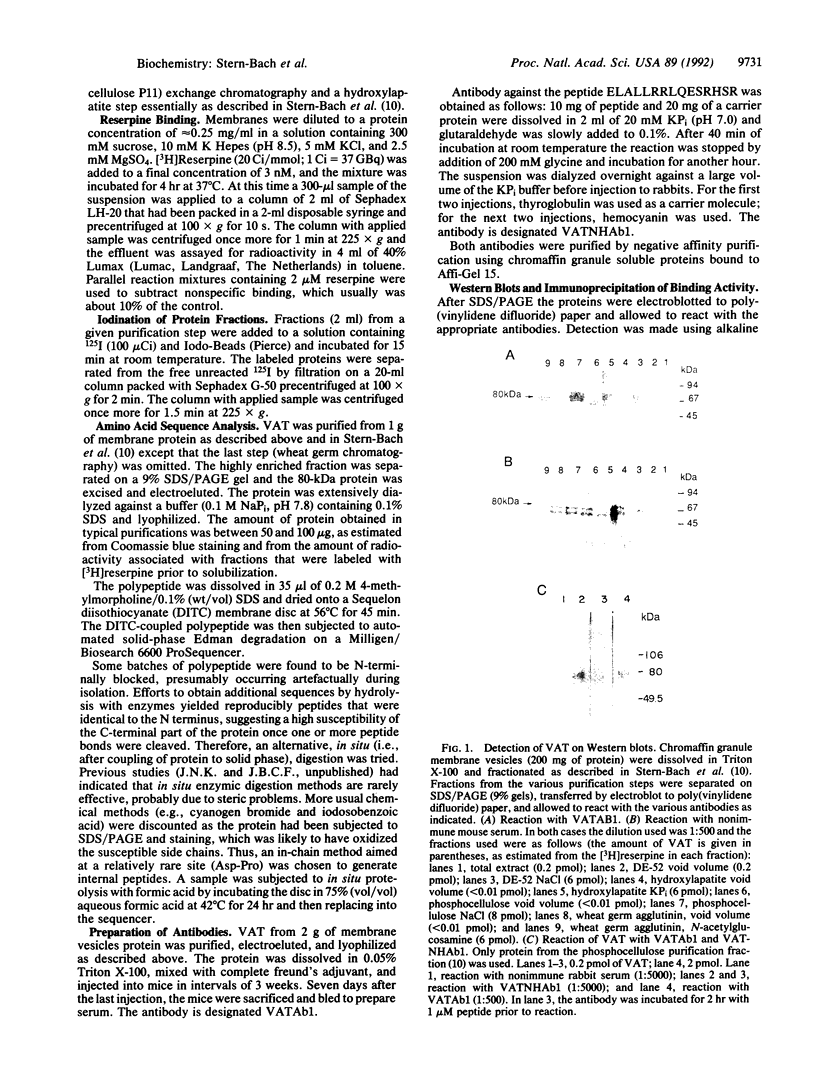

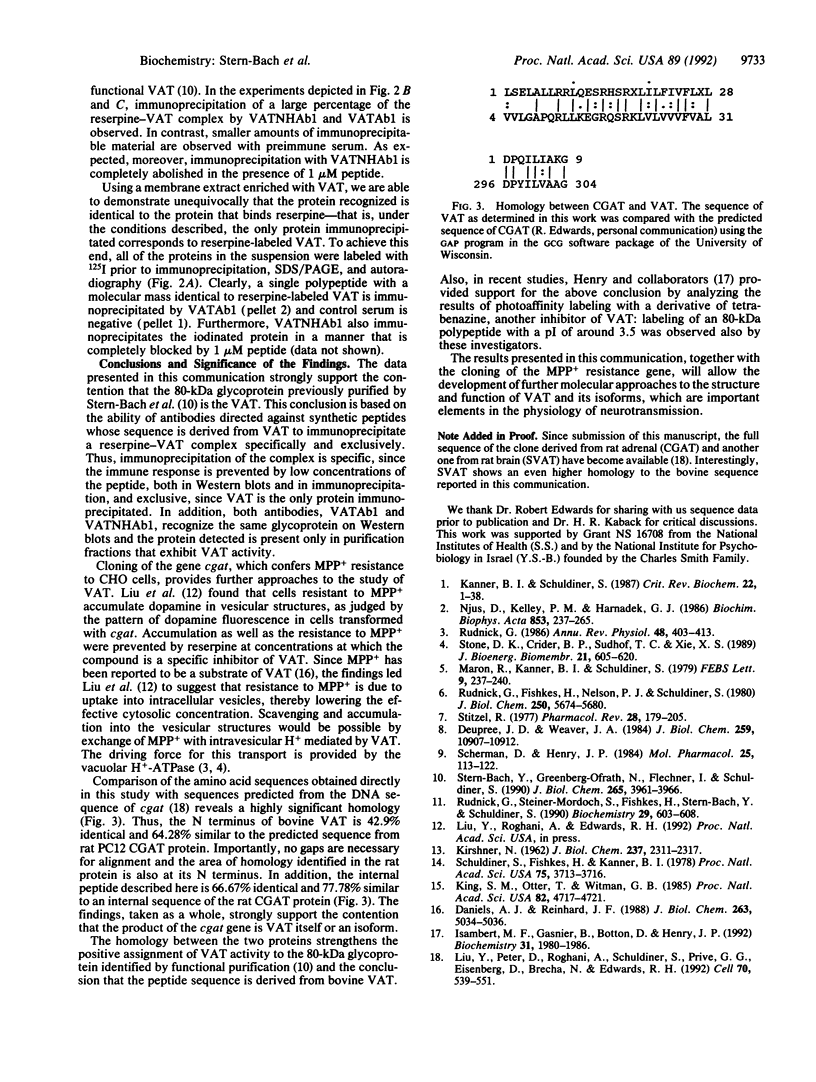

The vesicular amine transporter (VAT) catalyzes transport and storage of catechol and indolamines into subcellular organelles in a wide variety of cells. It plays a central role in neurotransmission and is the primary target for several pharmacological agents. One of the drugs, reserpine, binds very tightly to the transporter and remains bound even after solubilization, a finding that has proven useful for purification of the transporter from bovine adrenal medulla in a fully functional state. The sequences of 26 N-terminal amino acids and of an additional 7-amino acid internal peptide are presented. Antibodies against a synthetic peptide based on the above sequences immunoprecipitate the transporter, confirming the conclusion that the peptide sequence is derived from bovine VAT. To our knowledge, documentation of sequences of vesicular neurotransmitter transporters has not been presented previously. In addition, the sequences obtained are highly homologous to the predicted sequence of a protein from PC12 cells that confers to Chinese hamster ovary cells resistance to 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+), an agent that causes parkinsonism in model systems, confirming the hypothesis that the protein conferring resistance to MPP+ is a VAT.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Daniels A. J., Reinhard J. F., Jr Energy-driven uptake of the neurotoxin 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium into chromaffin granules via the catecholamine transporter. J Biol Chem. 1988 Apr 15;263(11):5034–5036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deupree J. D., Weaver J. A. Identification and characterization of the catecholamine transporter in bovine chromaffin granules using [3H]reserpine. J Biol Chem. 1984 Sep 10;259(17):10907–10912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isambert M. F., Gasnier B., Botton D., Henry J. P. Characterization and purification of the monoamine transporter of bovine chromaffin granules. Biochemistry. 1992 Feb 25;31(7):1980–1986. doi: 10.1021/bi00122a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIRSHNER N. Uptake of catecholamines by a particulate fraction of the adrenal medulla. J Biol Chem. 1962 Jul;237:2311–2317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner B. I., Schuldiner S. Mechanism of transport and storage of neurotransmitters. CRC Crit Rev Biochem. 1987;22(1):1–38. doi: 10.3109/10409238709082546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King S. M., Otter T., Witman G. B. Characterization of monoclonal antibodies against Chlamydomonas flagellar dyneins by high-resolution protein blotting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Jul;82(14):4717–4721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.14.4717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Peter D., Roghani A., Schuldiner S., Privé G. G., Eisenberg D., Brecha N., Edwards R. H. A cDNA that suppresses MPP+ toxicity encodes a vesicular amine transporter. Cell. 1992 Aug 21;70(4):539–551. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90425-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maron R., Kanner B. I., Schuldiner S. The role of a transmembrane pH gradient in 5-hydroxy tryptamine uptake by synaptic vesicles from rat brain. FEBS Lett. 1979 Feb 15;98(2):237–240. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(79)80190-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njus D., Kelley P. M., Harnadek G. J. Bioenergetics of secretory vesicles. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;853(3-4):237–265. doi: 10.1016/0304-4173(87)90003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudnick G. ATP-driven H+ pumping into intracellular organelles. Annu Rev Physiol. 1986;48:403–413. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.48.030186.002155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudnick G., Steiner-Mordoch S. S., Fishkes H., Stern-Bach Y., Schuldiner S. Energetics of reserpine binding and occlusion by the chromaffin granule biogenic amine transporter. Biochemistry. 1990 Jan 23;29(3):603–608. doi: 10.1021/bi00455a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherman D., Henry J. P. Reserpine binding to bovine chromaffin granule membranes. Characterization and comparison with dihydrotetrabenazine binding. Mol Pharmacol. 1984 Jan;25(1):113–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuldiner S., Fishkes H., Kanner B. I. Role of a transmembrane pH gradient in epinephrine transport by chromaffin granule membrane vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978 Aug;75(8):3713–3716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern-Bach Y., Greenberg-Ofrath N., Flechner I., Schuldiner S. Identification and purification of a functional amine transporter from bovine chromaffin granules. J Biol Chem. 1990 Mar 5;265(7):3961–3966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzel R. E. The biological fate of reserpine. Pharmacol Rev. 1976 Sep;28(3):179–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone D. K., Crider B. P., Südhof T. C., Xie X. S. Vacuolar proton pumps. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1989 Oct;21(5):605–620. doi: 10.1007/BF00808116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]