Abstract

Objective

Our aim in this study was to examine the competing interest policies and procedures of organisations who develop and maintain patient decision aids.

Design

Descriptive and thematic analysis of data collected from a cross-sectional survey of patient decision aid developer's competing interest policies and disclosure forms.

Results

We contacted 25 organisations likely to meet the inclusion criteria. 12 eligible organisations provided data. 11 organisations did not reply and 2 declined to participate. Most patient decision aid developers recognise the need to consider the issue of competing interests. Assessment processes vary widely and, for the most part, are insufficiently robust to minimise the risk of competing interests. Only half of the 12 organisations had competing interest policies. Some considered disclosure to be sufficient, while others imposed differing levels of exclusion.

Conclusions

Patient decision aid developers do not have a consistent approach to managing competing interests. Some have developed policies and procedures, while others pay no attention to the issue. As is the case for clinical practice guidelines, increasing attention will need to be given to how the competing interests of contributors of evidence-based publications may influence materials, especially if they are designed for patient use.

Keywords: Competing Interest, Conflict of interest, patient decision aid, patient decision support

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Multiple sources were used to identify patient decision aid organisations.

Independent dual data extraction and coding.

Some patient decision aid organisations were unwilling to provide data.

Possible non-identification of some patient decision aid organisations.

Introduction

Identifying and managing financial and intellectual competing interests are increasingly recognised as a vital step when producing clinical practice guidelines for professionals.1 2 When similar information is developed for patients, such as in the form of a decision aid, it becomes even more important to minimise competing interests.

Clinical guideline recommendations are designed to influence clinical practice by disseminating the results of a rigorous analysis of scientific evidence. It is therefore critical to ensure that their messages are not biased by other interests. However, over many years, significant concerns have been raised about the financial relationships between guideline panel experts and commercial entities, typically pharmaceutical companies,3 and doubts have been voiced about the validity of recommendations. For example, Cosgrove4 reported that all members of the American Psychiatric Association's Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder had financial ties to the pharmaceutical industry. The response to these concerns in the domain of guidelines has been the development of strategies to better manage such relationships and to make them more transparent.2 5

Working to increase transparency and perhaps minimise competing interests by excluding contribution has even more relevance when developing information sources for patients, given they are arguably more vulnerable to bias than health professionals. There is a wide range of patient-facing information being produced, which falls into multiple types of knowledge tools.6 One category—patient decision aids—has been the subject of substantial research scrutiny and support over the past two decades. A systematic review of 115 trials has shown that they increase patient knowledge, accuracy of risk perception and, in some situations, significantly influence decisions about tests and treatments.7 In short, they have significant influence. In consequence, the International Patient Decision Aids Standards Collaboration has argued that patient decision aids should be as free as possible of competing interests.8

In 2013, Barry et al9 updated the International Patient Decision Aids Standards Collaboration criteria and suggested a more stringent approach to the disclosure of competing interests in patient decision aid development. However, it is unclear whether patient decision aid developers have addressed the issue of how competing interests are identified and managed. Pioneers in this field were, for the most part, working in academic settings, but as interest has grown and a market has emerged, larger organisations—both commercial and non-profit—have appeared. These organisations may accept funding from multiple sources, and recruit a range of contributors, clinical experts, patient advocates and others. They may also use existing evidence sources to provide up-to-date content. The need for transparency is clear. As with clinical practice guideline production, individual-level and institutional-level conflicts of interest should be disclosed and managed. Our aim in this study was to examine the competing interest policies and procedures of organisations who develop and maintain patient decision aids.

Methods

Participants

We identified organisations that were known to produce patient decision aids by using inventories, publications, academic networks, email groups and conference proceedings. Organisations were invited to participate in the study if they: (1) had produced five or more patient-facing decision aids that were publicly or commercially available as of June 2015, and (2) had actively maintained and updated those tools.

For the purpose of this study, we adapted the definition of patient decision aids used in the Cochrane systematic review of patient decision aids.7 Eligible organisations were those that produced interventions that: (1) help patients make deliberate informed healthcare decisions; (2) explicitly state the decision to be considered; (3) provide balanced evidence-based information about available options, describing their associated benefits, harms and probabilities; and (4) support patients to recognise and clarify preferences.

Data collection

A standard email was sent to organisations identified as possibly eligible requesting a copy of their competing interest policy and declaration of interest form(s), as well as any other documents used to manage the relevant competing interests of their contributors, writers or experts, and those involved in the evidence synthesis process (see online supplementary material). We also requested data about the number and format of the organisation's patient decision aids. If we received incomplete or unclear information, additional inquiries were made. Reminders were sent at 1 and 2 weeks, and non-responses were documented.

bmjopen-2016-012562supp.pdf (107.7KB, pdf)

After piloting a data extraction form, two researchers (M-AD and MD) independently tabulated data about the organisation's name, location, number of active patient decision aids available, patient decision aid access (free or commercial), and patient decision aid type (eg, paper, web or video-based, or other). Data were summarised regarding each organisation's competing interest approach: scope, principles, applicability, coverage and date of implementation.

Data analysis

To identify themes in the data, all documented competing interest policies received were examined using qualitative methods, specifically thematic analysis. Undocumented approaches to managing competing interests mentioned in verbal or email communications were not included in the thematic analysis. MD and AB independently reviewed the extracted data and developed a preliminary codebook, using three of the documents received. Discrepancies in coding were discussed with M-AD until a definitive codebook was agreed, and applied by MD and AB to all policy documents using ATLAS.ti V.1.0.34. Inconsistent coding was resolved by consultation with M-AD. Codes across organisations were compared. Each organisation was asked to verify our interpretation of data in relation to existence of a documented policy, disclosure form, their approach to exclusion where competing interests were identified, their active number of patient decision aids and whether the tools were available publically or commercially; factual errors were addressed. Authors who were also members of the Option Grid Collaborative did not extract, code or analyse data from that organisation. Option Grid Collaborative data were handled by UP and MD.

Results

Patient decision aid organisations

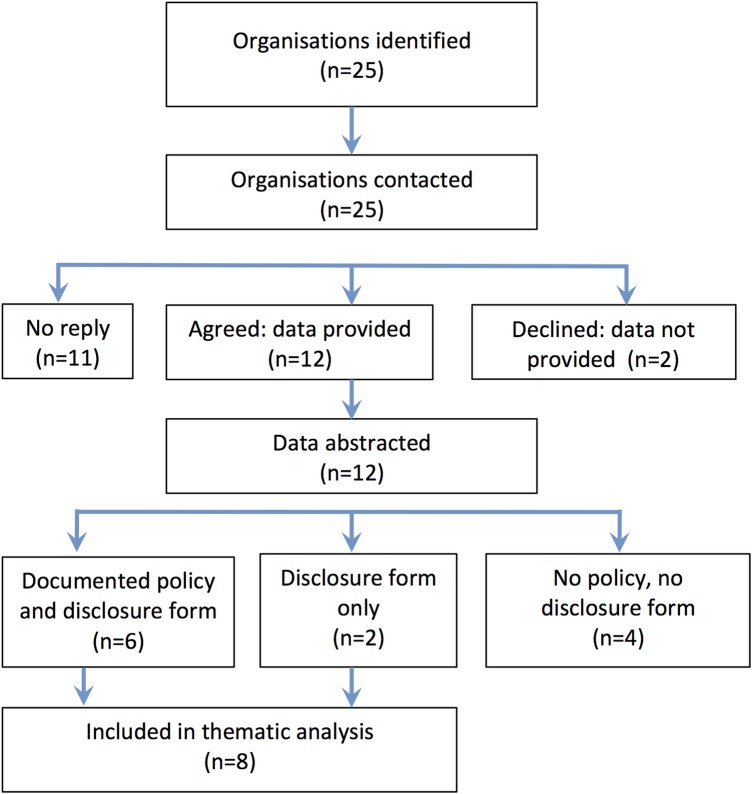

We contacted 25 organisations which we considered likely to meet the preset inclusion criteria (see figure 1). Twelve eligible organisations provided data (table 1). Eleven organisations did not reply and two declined to participate (see table 1 footnote). We do not know whether the non-responders were eligible, and we are unable to report data from those who declined participation. Eight of the 12 participating organisations were based in the USA, and one each in Australia, Canada, Germany and the Netherlands. The number of available decision aids, their format and mode of access varied across organisations. As of June 2015, the three largest developers were Healthwise, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and Health Dialog, with 180, 51 and 38 available patient decision aids, respectively. Other developers had smaller numbers of available tools. The majority of organisations were not-for-profit organisations (n=9). Most decision aids were web-based, often with print versions available. Eight out of 12 organisations allowed free access to the tools. Four organisations required payment or licences, although two of these organisations allowed limited free access to some tools.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of organisations from identification to inclusion in analysis.

Table 1.

Patient decision aid organisations* (as of June 2015)

| Organisation | Country | Decision aids | Format | Access | Profit status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality | USA | 51 | Web-based with PDF available | Free | NP |

| Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center | USA | 5 | Paper-based, some PDFs available online | Free | NP |

| Emmi Solutions | USA | 15+ | Video-based animation | Commercial | FP |

| Health Dialog | USA | 38 | Website, video, and/or booklet | Commercial† | FP |

| Healthwise | USA | 180 | Web-based with PDF available | Commercial† | NP |

| Mayo Clinic | USA | 5 | Electronic interactive tool, paper, video | Free | NP |

| Ottawa Hospital Research Institute | Canada | 16 | Web-based with PDF available | Free | NP |

| Option Grid Collaborative | USA | 37 | Electronic interactive tool, paper | Free | NP |

| PATIENT+ | The Netherlands | 10 | Web-based, video | Free | NP |

| University Medical Center Hamburg | Germany | 9 | Electronic interactive tool, paper | Free | NP |

| Sydney School of Public Health | Australia | 6 | Website, PDF and audio | Free | NP |

| WiserCare | USA | 10 | Web-based | Commercial | FP |

*Two of the following patient decision aid organisations declined participation and 11 did not reply to correspondence: British Medical Journal (UK), Choosing Wisely (USA), Decision Box, University of Laval (Canada); ‘Having a Baby’, University of Queensland (Australia), NHS Right Care (UK), The MedicalGuide (USA), Midwifery Information and Resource Service (UK), Queen Mary University (UK), Visualizing Health (USA), Vitality Group (USA), Wellvie (USA), Wiser Together (USA).

†Some public access granted.

FP, for profit; NP, not-for-profit.

Summary of competing interest approaches

Organisations producing patient decision aids do not have a consistent approach when dealing with competing interests. Some have written policies, others use an informal approach, and some collect information about competing interests without having a clear policy on how to manage identified conflicts (table 2). Six of the 12 participating organisations (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC), Health Dialog, Healthwise, Option Grid Collaborative, and Sydney School of Public Health) sent us their written competing interests policy. Two of the other six organisations reported following undocumented competing interest principles (Mayo Clinic and University Medical Center Hamburg), and another used criteria specified by the International Patient Decision Aids Standards Collaboration (Ottawa Hospital Research Institute). Two of the three for-profit organisations (Emmi Solutions and WiserCare) did not have a documented competing interest policy. Five of the 12 decision aid organisations had a rigorous approach to disclosing competing interests, defined as having a written policy, a disclosure of competing interests form, and a process of deciding whether or not to exclude contributors with competing interest. Six organisations barred contributors who had competing interests from contributing to development processes (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, CCHMC, Healthwise, Option Grid Collaborative, Sydney School of Public Health, and Mayo Clinic), all with exemptions possible, six did not. Eight of the 12 organisations used forms to collect information about competing interests. Of the other four organisations, two reported asking for informal disclosures. Four organisations did not have a formal method of identifying competing interest and did not have a documented policy. Five organisations disclosed competing interests on their patient decision aids, directly (Emmi Solutions, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, and PATIENT+) or by using associated web links (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and Healthwise).

Table 2.

Overview of organisational approaches to managing competing interests

| Documented policy and disclosure forms |

Disclosure forms, no policy |

No policy, No disclosure forms |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AHRQ | CCHMC | Health Dialog | Healthwise | Option Grid | Sydney | PATIENT+ | Ottawa | Emmi | Mayo | WiserCare | Hamburg | |

| Applies to contributor and family members | ✓ | ✓* | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Applies to financial interests only | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Applies beyond financial interests | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Full financial disclosure | ✓† | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Past interest disclosure | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Current interest disclosure | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Past and future interest disclosure | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Restrictions placed on contributors with competing interests | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Exclusion of contributors with competing interests | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Documented process for evaluating disclosures | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Documented policy exemptions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Competing interest principles followed | ✓‡ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Request informal disclosures | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Disclosure made on decision aid | ✓§ | ✓§ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

*Applies to lead editors only.

†Threshold for financial disclosure is role dependent.

‡Follow IPDAS.

§Web link to disclosure provided on decision aid.

AHRQ, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; CCHMC, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center; Emmi, Emmi Solutions; IPDAS, International Patient Decision Aids Standards; Mayo, Mayo Clinic; Ottawa, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; Option Grid, Option Grid Collaborative; Hamburg, University Medical Center Hamburg; Sydney, Sydney School of Public Health.

Thematic analysis of available competing interest policies and forms

Our thematic analysis included six policies and two interest disclosure forms (from organisations who had no documented policies), see table 2. We identified the following four main themes in the data: timeframe, application of policy, interests included or exempted, and management of disclosures.

Timeframe

Six organisations (four policies and two disclosure forms) mentioned timeframes for disclosure relevance. Healthwise considered past competing interests only, defined as those ‘received in the last year’. Health Dialog considered current competing interests only. Four organisations (Agency for Healthcare Research Quality, CCHMC, Option Grid Collaborative and PATIENT+) considered both past and future interests. Of those who specified that past interests must be declared, the applicable time period ranged from 12 to 36 months. We assume ‘future interests’ to imply current interests at time of disclosure. Similar inconsistent approaches were found regarding the timing at which information about interests was collected—whether at the start of development, or on a regular basis. Only four organisations requested proactive reporting of any changes in disclosures if new competing interests arose.

Application of policy

All six documents were clear that the policy applied to contributors, and included family members, but definitions varied. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Option Grid Collaborative included spouse, domestic partner and dependent children. Other organisations (CCHMC, Health Dialog and Healthwise) did not provide details. The Sydney School of Public Health's policy was the most extensive, including spouse, de facto partner, sexual partner, immediate family, close friend, a financial dependent or business partner.

Interests included and exempted

All six policies and one disclosure form mentioned the relevance of financial interests and this was defined in detail by four policies and one disclosure form. Healthwise and the Option Grid Collaborative required disclosure of financial interests, irrespective of the amount. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality described multiple disclosure thresholds, depending on the nature of an individual's involvement. Five organisations (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, CCHMC, Health Dialog, PATIENT+, and the Sydney School of Public Health) also required the disclosure of non-financial interests, such as potential intellectual interests or career advancement.

Three policies and one disclosure form indicated which types of interests did not require disclosure. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality does not require disclosure of service on advisory committees or review panels for public/non-profit entities, equity interests in a single entity below 5%, ownership in an institution if the institution is an applicant under the Small Business Innovation Research programme, income from seminars/lectures/teaching engagements for a public or non-profit entity, or for mutual or retirement funds. CCHMC does not require disclosure of salary, royalties or other remuneration received directly from CCHMC, equity interests in a single entity below 5%, royalties for publishing scholarly works or other writings, or of mutual or retirement funds. Healthwise also does not require disclosure of mutual or retirement funds. PATIENT+ does not require funding from public funding sources to be disclosed.

Management of disclosures

All organisations who had published a policy also had a method for collecting information about competing interests but less clarity about who would evaluate and act on the disclosures. Policies varied widely in terms of how to manage the disclosure of competing interests. None of the policies absolutely excluded individuals if competing interests were disclosed; all had some form of exemption. Five documented policies recommended, but did not require, excluding contributions from individuals with competing interests. Three of these five policies suggested that individuals should have limited roles in development or editorial processes. No policies formally required disclosed competing interests to be published directly on patient decision aids, although three organisations did so (Emmi Solutions, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute and PATIENT+).

Discussion

Main findings

Most, but not all, patient decision aid organisations recognise the need to consider the issue of competing interests. Nevertheless, processes vary widely and, for the most part, are insufficiently robust to minimise the risk that the information contained in these knowledge tools may be biased. At the time of analysis, we identified 12 organisations who had five or more tools in their inventory, indicating that relatively few number of organisations work in this field. Only half of these organisations had a documented competing interest policy, demonstrating a lack of attention to an area that is causing increasing concern for those summarising evidence for patient and professional consumption. The organisations who had developed policies varied widely in the restrictions imposed on those who declared competing interests, and none required competing interest disclosure to be published on patient decision aids. Some considered declarations to be sufficient, others imposed differing levels of exclusion from content development. No policies definitively prohibited the involvement of individuals with competing interests. The management of non-financial competing interests—for example, surgeons benefitting from a general uptake of surgical procedures in their discipline is a matter of ongoing debate. Some guideline producers, for example, the Institute of Medicine and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence are addressing this challenge by requiring higher standards from those who have ultimate editorial power, such as chairs of guideline panels.

Study strengths and weaknesses

We used multiple sources to identify patient decision aid organisations, and subsequently limited our focus to those who had developed and were actively maintaining five or more tools. These organisations therefore represent the most active organisations committed to the development of evidence-based knowledge tools designed to support patient-facing decision-making processes. Other organisations may exist that develop fewer tools but it is unlikely that they have significant numbers of patients accessing their products. The included organisations are likely to be aware of criteria published by the International Patient Decision Aids Standards Collaboration, which include recent recommendations regarding competing interest disclosure.8 Some organisations declined participation, and although we are confident that we identified the most relevant organisations, it is possible that other organisations exist. We achieved a rigorous analysis by adopting descriptive and qualitative methods, and independent dual data extraction and coding. Data provided by the Option Grid Collaborative were not extracted, coded or analysed by members of that organisation (AB, M-AD or GE).

Comparison with other studies

Previous studies have not examined the policies of organisations who develop and maintain patient decision aids, although the International Patient Decision Aids Standards Collaboration has consistently made recommendations regarding competing interests.8 Organisations in the USA at state and national levels are currently considering whether or not patient decision aids should be subjected to certification, as called for in section 3506 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.10 11 At the same time, the topic of competing interests among members of clinical guideline panels has also been under increasing scrutiny,12–14 with recent calls to minimise or avoid financial and professional conflicts during the development of guidelines.14 The common thread seems to be concern about trustworthy summary of scientific evidence, whether intended for professionals or patients.

In a systematic literature search of articles from 2001 to 2011, Barry et al9 found no articles that examined the impact of COI disclosure in patient decision aids on reducing bias in decision-making, showing a lack of attention to the topic in the scientific community. Their recommendations focused on transparent reporting of funding sources and whether organisations or individuals stood to gain or lose by the choices made by patients. While these recommendations strengthen previous recommendations made by the International Patient Decision Aids Standards Collaboration, they are less comprehensive than policies used by some organisations included in this analysis.

Practice implications

This study illustrates the wide variation in the attention given to competing interests when developing information materials called patient decision aids. The most rigorous approach was illustrated by the policy adopted by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, while some organisations paid no attention to the issue, or assumed that informal processes were sufficient protection. Although the International Patient Decision Aids Standards Collaboration has produced ‘quality’ criteria, patient decision aid producers do not seem to have adopted the need to address the issue of competing interests, and to systematically disclose this information on decision aids or supporting documents. Indeed, some organisations indicated that this study had prompted them to pay more attention to this issue and review or develop policies. As observed in the domain of clinical practice guidelines, increasing attention needs to be given to how the competing interests of contributors, authors and editors will influence the process of evidence synthesis, especially for patient facing-materials, and how they need to be disclosed, reduced and managed—and, in certain cases, eliminated.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the organisations who took part in the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: GE and M-AD planned and designed the study and protocol. GE, M-AD and MD initiated and managed the correspondence with the participating organisations. AB, M-AD and GE developed the data extraction tool. MD and M-AD extracted all data. All data were analysed by AB and MD, with the exception of Option Grid Collaborative data, which was analysed by MD and UP. M-AD, GE and UP provided advice and guidance on the design, data collection and analysis. UP provided advice on interpreting the results from a legal standpoint. All authors contributed to the manuscript, writing and approved the final draft.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: GE, M-AD and AB, authors on this paper, lead the Option Grid Collaborative and unincorporated association of individuals engaged in the development and dissemination of Option Grid decision aids for clinical encounters under the auspices of the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice. All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interests form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data presented in this manuscript are available by request from the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Norris SL, Holmer HK, Ogden LA et al. Conflict of interest in clinical practice guideline development: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e25153 10.1371/journal.pone.0025153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vandvik PO, Brandt L, Alonso-Coello P et al. Creating clinical practice guidelines we can trust, use, and share: a new era is imminent. Chest 2013;144:381–9. 10.1378/chest.13-0746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moynihan RN, Cooke GPE, Doust JA et al. Expanding disease definitions in guidelines and expert panel ties to industry: a cross-sectional study of common conditions in the United States. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001500 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cosgrove L, Bursztajn HJ, Erlich DR et al. Conflicts of interest and the quality of recommendations in clinical guidelines. J Eval Clin Pract 2013;19:674–81. 10.1111/jep.12016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akl EA, El-Hachem P, Abou-Haidar H et al. Considering intellectual, in addition to financial, conflicts of interest proved important in a clinical practice guideline: a descriptive study. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:1222–8. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graham I, Logan J. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof 2006;26:13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stacey D, Légaré F, Col NF et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;1:CD001431 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Volk RJ, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Stacey D et al. Ten years of the International Patient Decision Aid Standards Collaboration: evolution of the core dimensions for assessing the quality of patient decision aids. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2013;13(Suppl 2):S1 10.1186/1472-6947-13-S2-S1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barry MJ, Chan E, Moulton B et al. Disclosing conflicts of interest in patient decision aids. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2013;13(Suppl 2):S3 10.1186/1472-6947-13-S2-S3http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-13-S2-S3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Senate and House of Representatives 2010. . The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Washington, United States of America. http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/rights/law/patient-protection.pdf.

- 11.Alston C, Berger Z, Brownlee S et al. Shared Decision-Making Strategies for Best Care: Patient Decision Aids and Beyond. 2014.

- 12.Lo B, Field MJ. Conflicts of Interest and Development of Clinical Practice Guidelines 2009. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK22928/ (accessed 28 Mar 2016).

- 13.Loewenstein G, Sah S, Cain DM. The unintended consequences of conflict of interest disclosure. JAMA 2012;307:669–70. 10.1001/jama.2012.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lenzer J, Hoffman JR, Furberg CD et al. Ensuring the integrity of clinical practice guidelines: a tool for protecting patients. BMJ 2013;347:f5535 10.1136/bmj.f5535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-012562supp.pdf (107.7KB, pdf)