Abstract

Iron toxicity is a nutrient disorder that severely affects crop development and yield in some soil conditions. Vacuolar detoxification of metal stress is an important strategy for plants to survive and adapt to this adverse environment. Vacuolar iron transporter (VIT) members are involved in this process and play essential roles in iron storage and transport. In this study, we identified a rapeseed VIT gene BnMEB2 (BnaC07g30170D) homologs to Arabidopsis MEB2 (At5g24290). Transient expression analysis revealed that BnMEB2 was localized to the vacuolar membrane. Q-PCR detection showed a high expression of BnMEB2 in mature (60-day-old) leaves and could be obviously induced by exogenous iron stress in both roots and leaves. Over-expressed BnMEB2 in both Arabidopsis wild type and meb2 mutant seedlings resulted in greatly improved iron tolerability with no significant changes in the expression level of other VIT genes. The mutant meb2 grew slowly and its root hair elongation was inhibited under high iron concentration condition while BnMEB2 over-expressed transgenic plants of the mutant restored the phenotypes with apparently higher iron storage in roots and dramatically increased iron content in the whole plant. Taken together, these results suggested that BnMEB2 was a VIT gene in rapeseed which was necessary for safe storage and vacuole detoxification function of excess iron to enhance the tolerance of iron toxicity. This research sheds light on a potentially new strategy for attenuating hazardous metal stress from environment and improving iron biofortification in Brassicaceae crops.

Keywords: Brassica napus, BnMEB2, vacuolar iron transporter, vacuolar sequestration, iron tolerance

Introduction

Iron is an essential micronutrient for plant growth and human health. It also functions as a required cofactor for various enzymes in DNA biosynthesis and in the electron-transport chains of respiration and photosynthesis (Curie and Briat, 2003; Conte and Walker, 2011). However, tight control of iron acquisition and translocation helps to keep iron homeostasis which is crucial step for all plants survival and proliferation. Iron deficiency in uptake or absorption leads to chlorosis in the young leaves and retarded growth, consequently resulting in reduced photosynthetic efficiency and crop productivity (Wu et al., 2010). In contrast, iron excess can cause severe functional disorders and cellular damages which is highly reactive and toxic (Briat et al., 2010). With the rapid development of modern industry, urban pollution and extensive application of agricultural chemical substances to the soil increased the toxicity of metal pollution which in turn limited the grain production. The breeding of tolerant crop varieties becomes a powerful approach to address the problem of metal toxicity.

Plants have evolved two distinct strategies for iron acquisition (Hindt and Guerinot, 2012; Jain and Connolly, 2013). Dicots and non-graminaceous plants secrete protons into the rhizosphere to enhance the solubility of ferric complex (Fe3+), then the root ferric chelate reductase (FRO2) reduces Fe3+ (ferric ion) into a more soluble Fe2+ (ferrous ion) (Robinson et al., 1999). Finally iron regulated transporter1 (IRT1)-type ferrous transporters move Fe2+ across the root epidermal plasma membrane (Vert et al., 2002). Interestingly, the graminaceous plants possess another unique strategy in the uptake of iron. Plants secrete the mugineic acid, a phytosiderophores (PS), into the rhizosphere to form the chelate complex of Fe3+-PS (Ishimaru et al., 2006) and then absorb it into root cells by the yellow stripe 1 (YS1) transporter (Curie et al., 2001). Following the initial uptake of iron into root cells, several key genes such as AtFRD3 (Durrett et al., 2007), OsFRDL1 (Yokosho et al., 2009), PEZ1 (Ishimaru et al., 2011), FPN1 (Morrissey et al., 2009) and YSL (Curie et al., 2009; Chu et al., 2010) have been reported to unload and transport iron from root to the above-ground portions of plant such as shoot, leaf and seed for development (Conte and Walker, 2011). Additionally, to reach their final destination within the plant, iron also must be delivered to the appropriate cell compartments for utilization (Kobayashi and Nishizawa, 2012). For instance, PIC1 and FRO7 are required for transportation of iron to chloroplast (Duy et al., 2007; Jeong and Guerinot, 2009) and MIT is responsible for iron import into the mitochondrion (Bashir et al., 2011). Overall, the emerging information on iron transporters provides new insights to comprehensively understand how plants partition iron among different tissues and subcellular organelles (Kim and Guerinot, 2007).

Despite its importance, any excess of iron is highly toxic. Vacuole is a pivotal organelle for storing iron to avoid deficiency and toxicity during iron homeostasis regulation (Mendoza-Cózatl et al., 2011; Peng and Gong, 2014). Vacuolar sequestration serves as a safe iron storage strategy for detoxifying excess iron, and vacuolar iron transporters (VITs) were previously found to play significant roles in this process (Slavic et al., 2016). When challenged by a high iron environment, VITs can maintain iron within an optimal physiological range or deliver iron to enable the cell growth (Zhang et al., 2012; Narayanan et al., 2015). VITs help transportation of iron into vacuoles which function as buffering pools with adjustable sequestration capacity along with the environmental change to prevent cellular toxicity (Peng and Gong, 2014). In Arabidopsis, AtVIT1 is one of the main transporters which allows iron uptake into vacuoles when exposed to iron excess (Kim et al., 2006). In contrast, AtNRAMP3 and AtNRAMP4 act as retrievers to export iron from vacuoles for cell growth at different stages of plant life (Lanquar et al., 2005). AtMEB1 and AtMEB2 are functional homologs of the yeast iron transporter CCC1, which serve as iron transporters to reduce the toxicity in yeast ccc1 mutant under high iron concentration condition (Yamada et al., 2013). Moreover, two orthologs of AtVIT1 in rice, OsVIT1 and OsVIT2 have been shown to modulate iron translocation between flag leaves and seeds (Zhang et al., 2012). TgVIT1 is required for the development of blue color in the bottom of petal by controlling iron content (Momonoi et al., 2009). In addition to their roles in transporting iron, VIT members are poorly selective to divalent metal ions. Other potentially toxic metals can transport into vacuoles along with iron, such as Zn2+ and Mn2+. For instance, OsVIT1 and OsVIT2 can modulate Zn storage in the vacuole of flag leaf (Zhang et al., 2012); AtNRAMP3 and AtNRAMP4 help in the uptake of Mn2+ to photosystem II in mesophyll cells (Lanquar et al., 2010). Thus, a better understanding of VITs for uptake and allocation iron in plants is of great importance for iron homeostasis.

In contrast to the model plant of Arabidopsis and rice, relatively little is known about the contribution of VITs in Brassica napus (rapeseed). B. napus is an important oil crop cultivated in worldwide for providing human nutrition and oil production. Rape industry faces an urgent challenge of toxic metal pollution owing to rapid expansion and high-speed development of the industry. The mechanism of tolerance to metal toxicity in rape appears to be complex. In this report, a homolog of AtMEB2 named as BnMEB2 which belongs to the VIT family was identified in B. napus. BnMEB2 was localized on the vacuolar membrane and participated in vacuolar sequestration of iron storage to enhance iron tolerance of the plant.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Brassica napus cultivar Zhongshuang NO.9, Arabidopsis wild type (Col-0) and meb2 mutant (GK-059D30, a T-DNA insertion in the second exon of MEB2) were used in this study. Seedlings of rapeseed cultivar Zhongshuang NO.9 were grown in 10 l boxes containing Hoagland nutrient solution in a greenhouse with 25°C light/22°C dark cycles under normal light conditions. The Arabidopsis wild type (Col-0), meb2 and transgenic lines were grown on Murashige and Skoog (MS) plates containing 1% sucrose and 0.8% agar. Seedlings were grown under a 16-h-light/8-h-dark condition at 22°C in a growth chamber with light.

Identification and Cloning of BnMEB2

The B. napus genome was downloaded from the Genoscope Genome Database1 (Chalhoub et al., 2014). To identify homologs in B. napus, AtMEB2 (At5g24290) was used as initial protein queries to search against Genoscope Genome Database based on BLASTP with the score value of ≥100 and e-value ≤ e-10. Conserved VIT domain in the candidate sequences were detected by Pfam database2 on line. At last, two candidate genes were identified such as BnaC07g30170D and BnaA06g26800D. According to the sequence information of these two genes, specific primers (Forward 5′-ATGGACCGACCAGCTGACG-3′ and Reverse 5′-TTAAAGGGAAGTAAACCGGTATTC-3′) were designed with the Primer Premier 5.0 (PREMIER Biosoft International, USA). The coding sequence (CDS) was amplified using B. napus cultivar Zhongshuang NO.9 cDNA as the template and sequenced. To illustrate the structure of intron, exon and VIT domain of the candidate genes, fancygene database3 was used to draw the gene structure according to the full-length genome from Genoscope Genome Database and coding sequence from sequencing. The sequences of candidate genes were aligned by using Clustal W (Thompson et al., 1994; Rambaldi and Ciccarelli, 2009). The 3D protein structure model of the homologs regions was predicted by SWISS-MODEL and was analyzed by using SPDBV4.10 (Guex and Peitsch, 1997).

Subcellular Localization of BnMEB2

Cellular localization of the BnMEB2 protein was examined by transient expression of a BnMEB2::GFP fusion protein. The open reading frames (ORFs) of BnMEB2 without a stop codon were amplified by using the following primers (Forward 5′-GACTGGTACGAGCTCGGTACCATGGACCGACCAGCTGACG-3′; Reverse 5′-GCCCTTGCTCACCATGGATCCAAGGGAAGTAAACCGGTATTCCTC-3′). The underlined sections in primer sequences indicated KpnI and BamHI restriction sites respectively. PCR products were recombined into pUC19-35Spro::GFP (previously modified and constructed by our lab) to generate the expression vector 35Spro::BnMEB2::GFP by using ClonExpress MultiS One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme). The detailed information about these vectors was shown in the Supplementary Figure S1. The resulted constructs together with the positive control 35Spro::GFP were transiently expressed in Arabidopsis protoplasts via polyethylene glycol-mediated transformation (Yoo et al., 2007). Furthermore, the plasmid constructs were also delivered into onion epidermal cells for transiently expression by DNA particle bombardment using the PDS-1000/He Biolistic Particle Delivery System (Bio-Rad) as described by Xie et al. (2014). GFP fluorescence was then observed with a confocal microscope (Nikon A1) at 16 h after transfection.

BnMEB2 Over-Expression and Plant Transformation

Due to the high similarity between BnaC07g30170D and BnaA06g26800D, only CDS fragment of BnaC07g30170D was constructed into pBWA(V)BS vector4 and verified by sequencing to create a 35Spro::BnMEB2 over-expression vector, in which target gene expression was under the control of CaMV 35S promoter. The full-length cDNAs of BnMEB2 were amplified with the following primers (Forward 5′-CGGAATTCATGGACCGACCAGCTGACG-3′ and Reverse 5′-CGGGATCCTTAAAGGGAAGTAAACCGGTATTC-3′). The underlined sections in primer sequences indicated EcoRI and BamHI restriction sites respectively. Plasmid of 35S::BnMEB2 was introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 by electroporation and was transformed into Arabidopsis wild type (col-0) and meb2 mutant by floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). Transgenic plants were selected by herbicide spraying. BAR-resistant and PCR-positive transgenic plants were transferred to a greenhouse and maintained up to T2 generation. Transgenic lines with high expression level of BnMEB2 were selected and used for further analysis.

qRT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA for quantitative RT-PCR was extracted from the rapeseed and Arabidopsis samples using the RNeasy Plant Minikit (Qiagen, USA) and was reverse transcribed with SuperScriptTM III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. qRT-PCR was performed by using SYBR Green Real-time PCR Master Mix (Bio-Rad, USA) in 20 μl reaction mixture and run on CFX96 Real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad). Oilseed rape and Arabidopsis β-actin genes (AF111812, AT1G13180) were used as internal standard. All assays for target genes were conducted with three biological repeats, each with three technical repeats. Primers used in qRT-PCR are listed in Supplementary Table S1. The quantification of threshold cycle (CT) value analysis was achieved using the 2(-ΔCT) method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

High Iron Concentration Treatment Analysis

Seeds of B. napus cultivar Zhongshuang NO.9 were germinated and grown in 1/2 Hoagland nutrient solution. At the eighth day, one half of the seedlings were transferred to Hoagland nutrient solution while the other half was transferred to Hoagland nutrient solution with 0.5 mM FeSO4 for high iron concentration treatments. Roots and leaves were collected at 1, 2, and 3 days after transferred under the normal and high iron concentration conditions and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was isolated to determine the mRNA level of BnMEB2. Moreover, at least three replicates of Arabidopsis transgenic lines (35S::BnMEB2/WT and 35S::BnMEB2/meb2), wild type (col-0) and meb2 were grown on MS medium with a series of high iron concentration treatments (0.2-1 mM FeSO4) for 20 days. These seedlings were collected and their total RNAs were isolated to detect the expression level of other key VIT genes.

Perls’ Staining and Iron Quantification

Arabidopsis roots were stained with Perls’ solution according to previous study (Green and Rogers, 2004). Equal volume of 4% (v/v) HCl and 4% (w/v) potassium ferrocyanide were mixed immediately prior to use. The mixed solution was vacuum infiltrated into 10-day-old Arabidopsis seedlings for approximately 15 min. Seedlings were rinsed in ultrapure water for three times. The Perls’ staining samples were observed immediately in whole roots using an Olympus IX71 microscope. The method for iron quantification was minor modified from those described by Cassin et al. (2009) and Li et al. (2013). Harvested seedlings were washed for 5 min in a solution containing 5 mM CaSO4 and 10 mM EDTA, then dried at 70°C for 3 days and weighted. Approximately 300 mg of dry tissue was digested completely in 10 mL 70% HNO3 at 200°C for 2 h. The iron contents in these samples were measured by inductively coupled plasma spectrometry SPS3000 (Seiko, Tokyo, Japan) and conducted with three biological repeats.

Results

BnMEB2 Belongs to VIT Family

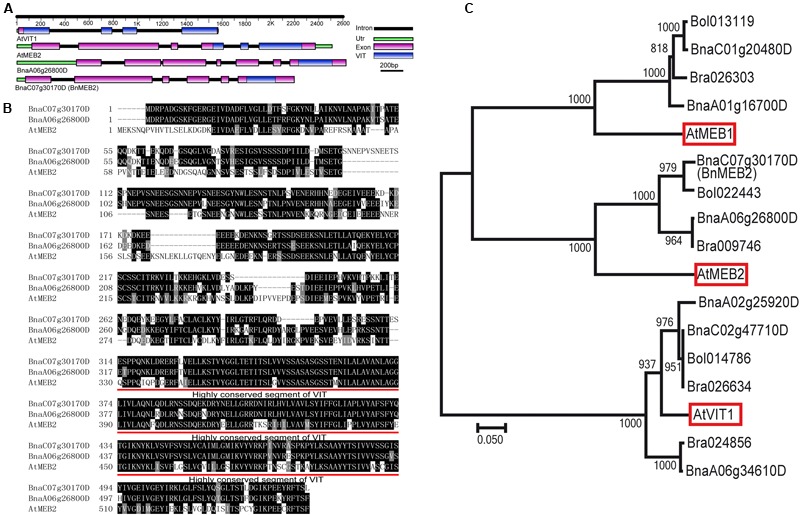

To identify the homologs in B. napus, AtMEB2 was used as protein queries for BLASTP and two copies (BnaC07g30170D and BnaA06g26800D) were identified from B. napus genome. Based on the information in Genoscope Genome Database, full-length cDNA fragments in rapeseed cultivar Zhongshuang NO.9 were amplified by high-fidelity RT-PCR. BnaC07g30170D locates at C07 chromosome, which consists of six exons and five introns. BnaA06g26800D locates at A06 chromosome, which consists of seven exons and six introns. More importantly, same as the well-known VIT family members in Arabidopsis such as AtVIT1 and AtMEB2, BnaC07g30170D and BnaA06g26800D also contained VIT domain. Interestingly, VIT domains of AtVIT1 and AtMEB2 were separated by three or two introns but were fully integrated in the last exon of BnaC07g30170D and BnaA06g26800D (Figure 1A). BnaC07g30170D and BnaA06g26800D encode putative protein with 534 and 537 amino acids respectively, and show a high similarity with AtMEB2. Especially, VIT domain shared over 85% sequence similarity among AtMEB2, BnaC07g30170D and BnaA06g26800D (Figure 1B). Phylogenetic analysis indicated that BnaC07g30170D and BnaA06g26800D had a high level of similarity to these putative plant VIT proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana and Brassiceae family (Figure 1C). BnaC07g30170D, BnaA06g26800D and AtMEB2 were clustered into one group and BnaC07g30170D was more similar to AtMEB2 than that of BnaC07g30170D in the phylogenetic analysis. In addition, BnaC07g30170D has a higher similarity of protein sequence to AtMEB2 than that of BnaA06g26800D in their highly conserved sequence of VIT domains, thus BnaC07g30170D was designated as BnMEB2 for further study. Furthermore, protein 3D structure model showed that AtVIT1, AtMEB2 and BnMEB2 shared similar structures within VIT domain (Supplementary Figure S2). Therefore, these results suggest that BnMEB2 belongs to the VIT family.

FIGURE 1.

Sequence and structure information of BnMEB2. (A) Gene structural of AtVIT1, AtMEB2 and BnMEB2. The different color lines and boxes represent introns, UTR, exons and VIT domain, respectively. Lengths of exons and introns of each gene are displayed proportionally. (B) Amino acid sequence alignment with AtMEB2. The identical amino acid residues were black-shaded and similar ones were indicated by gray-shaded. Their highly conserved sequence of VIT domains are underlined. (C) Phylogenetic relationship of BnMEB2, the vacuolar iron transporters AtVIT1 (At2g01770), AtMEB1 (At4g27860), AtMEB2 (At5g24290) from Arabidopsis thaliana and their homologs from Brassica rapa, Brassica oleracea and Brassica napus. The scale bar represents the branch lengths.

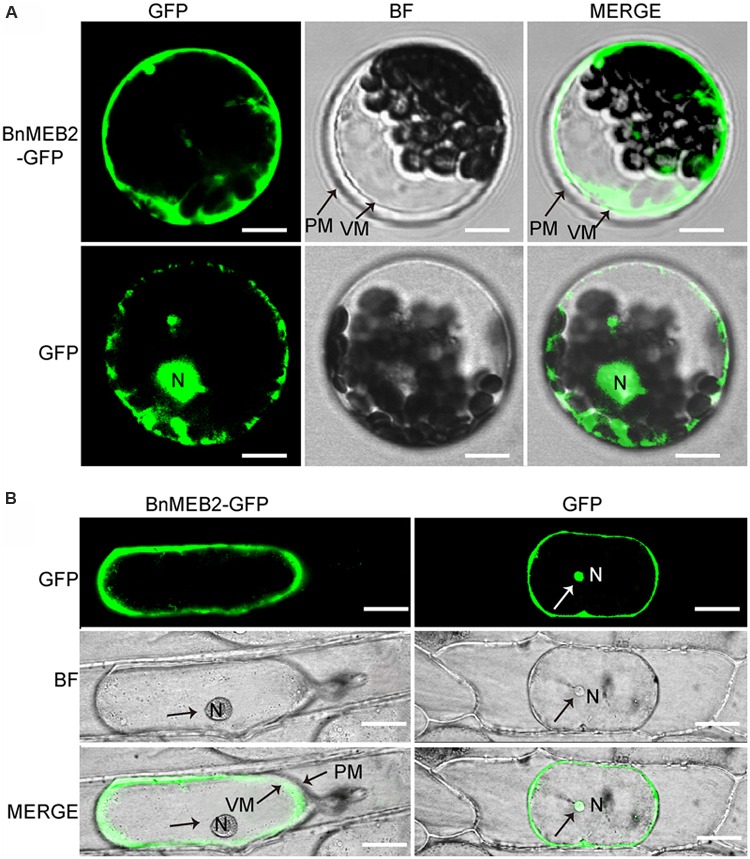

BnMEB2 Locates on the Vacuolar Membrane

The VITs were previously found to locate on vacuolar membrane to mediate vacuolar sequestration of iron storage and acted as metal transporters, such as TgVIT1 (Momonoi et al., 2009), AtVTL1 and AtVTL2 (Gollhofer et al., 2014). The subcellular localization of BnMEB2 was investigated by transiently expression in Arabidopsis protoplasts and onion epidermal cells. BnMEB2 was fused in frame to GFP (green fluorescent protein) in the expression vector pUC19-35Spro::GFP. 35Spro::BnMEB2::GFP fusion construct and the GFP alone control 35Spro::GFP, both driven by 35S promoter were introduced into Arabidopsis protoplasts. BnMEB2::GFP fusion protein was observed exclusively in the vacuolar membrane while GFP alone was found throughout the control cells (Figure 2A). Furthermore, the subcellular localization of BnMEB2 was also investigated by expression of 35Spro::BnMEB2::GFP in onion epidermal cells. BnMEB2::GFP fluorescence was observed in the vacuolar membrane too (Figure 2B). The above results showed that BnMEB2 was localized on the vacuolar membrane and may also be a vacuolar membrane transporter.

FIGURE 2.

Subcellular localization of BnMEB2. (A) Subcellular localization of BnMEB2 in Arabidopsis protoplasts. Protoplasts were isolated from Arabidopsis seedlings and transformed with 35Spro::BnMEB2::GFP and 35Spro::GFP respectively. Bars = 10 μm. (B) Subcellular localization of BnMEB2 in onion epidermal cells. Bars = 20 μm. The 35Spro::GFP constructs were used as positive controls. Green fluorescence, bright field and merged images were taken under confocal. N, nucleus; VM, vacuole membrane; PM, plasma membrane.

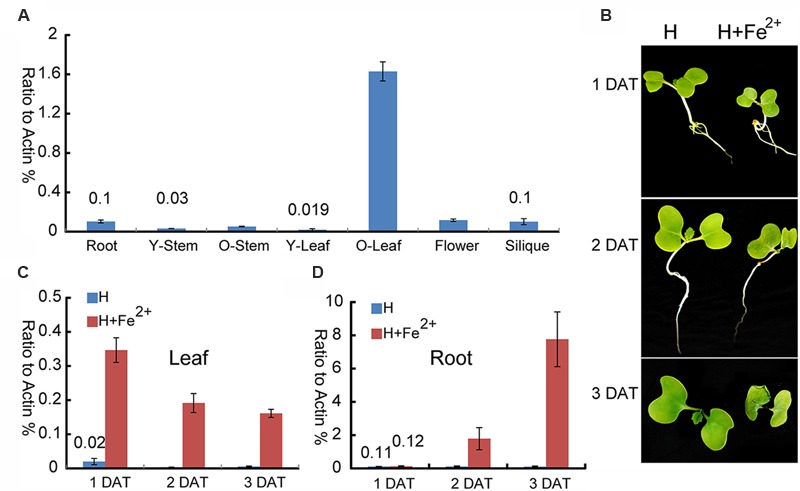

BnMEB2 Is Highly Expressed in Mature Leaves and Can Be Induced by High Iron Concentration Treatment

To provide deep insight into the function of BnMEB2 during different physiological processes, expression pattern was examined in various tissues. Transcription levels of BnMEB2 in all tissues of rapeseed, including root, young stem (14-day-old stem), mature stem (60-day-old stem), young leaf (14-day-old leaf), mature leaf (60-day-old leaf), flower and silique were detected by qRT-PCR (Figure 3A). BnMEB2 was substantially higher expressed in mature leaves and weakly detected in other tissues including young stems and young leaves. With the storage role of leaves, this result suggested that BnMEB2 may function and coordinate to mediate iron storage in the source tissues for human health. Interestingly, the expression of BnMEB2 in mature stems was higher than that of young stems, and it was the same between mature and young leaves, indicating that BnMEB2 may be highly expressed in mature tissues for advantage of iron storage during plant life cycle.

FIGURE 3.

Expression patterns of BnMEB2 in Brassica napus. (A) Relative expression levels of BnMEB2 in Brassica napus. BnActin was used as an internal control. Root, 10-day-old roots; Y-Stem, 14-day-old stems; O-Stem, 60-day-old stems; Y-Leaf, 14-day-old leaves; O-Leaf, 60-day-old leaves; (B) The Brassica napus seedlings in response to the normal Hoagland nutrient solution (H) and high concentration iron treatment (H + Fe2+) conditions. DAT represents days after treatments. (C,D) The expression of BnMEB2 in rapeseed seedling leaves and roots under normal and high concentration iron treatments. Values are the means ± SD of three independent experiments.

To further investigate whether BnMEB2 is associated with iron transportation, transcriptional abundance of BnMEB2 in B. napus roots and leaves were analyzed under normal Hoagland nutrient solution and high iron concentration treatment (Hoagland nutrient solution added with 500 μM FeSO4). The rape seedlings when treated with 500 μM FeSO4 showed a slow growth, yellowing of leaves and shrinking of roots when compared with the control. Three days after treatment (3 DAT), leaves of rape seedlings were obviously shrinked (Figure 3B). The expression of BnMEB2 was markedly induced by high iron concentration treatment in both roots and leaves. The transcription level of BnMEB2 was up-regulated at least 10-fold after 2 days treatment, and more than 70-fold for 3 days after treatment in seedling roots (Figure 3C). Similar results were obtained in leaves, where significant induction of BnMEB2 was observed after 1, 2, and 3 days of high iron concentration treatment (Figure 3D). Furthermore, in comparison with roots, the induction of BnMEB2 expression was faster in young leaves. In young leaves, at the first day after high iron concentration treatment did BnMEB2 show remarkably higher expression than the second and third days under the same treatment. This phenomenon might be responsible for iron storage in leaves to detoxify the iron stress, while roots are mainly responsible for iron acquisition. Moreover, the expression of BnMEB2 was higher in young roots than in young leaves (Figures 3C,D). Taken together, these data imply that BnMEB2 was highly induced by high iron concentration treatment and was involved in iron transportation.

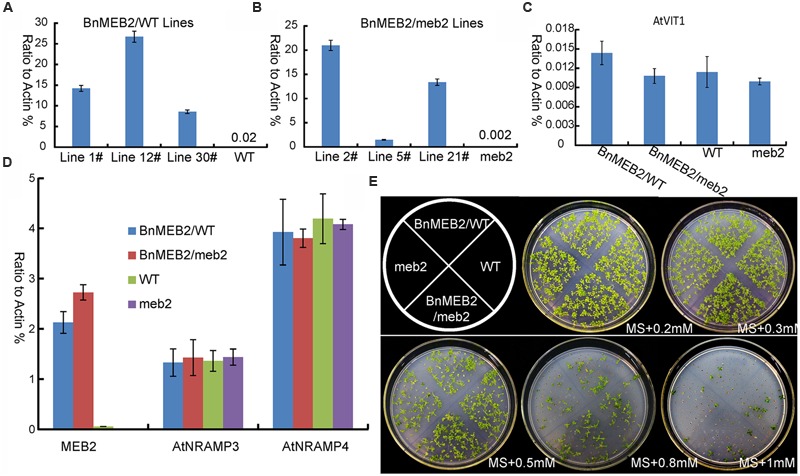

Over-Expression of BnMEB2 Enhances the Tolerance of High Iron Concentration stress in Arabidopsis Transgenic Plants

To better understand the role of BnMEB2 in regulation the tolerance of high iron concentration stress, BnMEB2 over-expression vector driven by 35S promoter was constructed and transformed into Arabidopsis wild type (col-0) and meb2 (defined as 35S::BnMEB2/WT and 35S::BnMEB2/meb2, respectively). A total of three 35S::BnMEB2/WT (line 1#, 12#, and 30#) and three 35S::BnMEB2/meb2 (line 2#, 5#, and 21#) transgenic lines were selected and purified. qRT-PCR analysis showed that the expression levels of BnMEB2 in transgenic plants with either WT or meb2 background were significantly increased as compared with wild type and meb2 mutant (Figures 4A,B). To verify the functions of BnMEB2 in vivo, these transgenic lines were challenged with high iron concentration stress. 35S::BnMEB2/WT transgenic line 1#, 35S::BnMEB2/meb2 transgenic line 21#, wild type and meb2 were sowed on MS medium under a series of high iron concentration conditions (0.2 mM, 0.3 mM, 0.5 mM, 0.8 mM and 1 mM FeSO4) and cultured for 20 days. As shown in Figure 4E, the high iron concentration significantly impacted on seeds germination at the seedling stage. 35S::BnMEB2/WT and 35S::BnMEB2/meb2 transgenic plants had a higher seeds germination rate and more tolerated to high iron environment than that of meb2, especially when the high iron concentration increasing to more than 0.5 mM FeSO4. Over-expression of BnMEB2 restored and increased the germination rate of meb2 in the complementary lines 35S::BnMEB2/meb2. These results showed that 35S::BnMEB2/WT and 35S::BnMEB2/meb2 transgenic plants had stronger high iron tolerance than that of meb2, indicating that BnMEB2 was involved in high iron tolerance.

FIGURE 4.

Improved iron tolerance and the expression of vacuoleiron transporter genes in transgenic Arabidopsis. (A,B) Expression level of MEB2 in BnMEB2 over-expression in Arabidopsis wild type (WT, col-0) background (35S::BnMEB2/WT) and mutant meb2 (35S::BnMEB2/meb2) background transgenic lines. Seedlings were grown for 30 days and total RNAs were extracted for quantitative RT-PCR analysis. (C,D) The expression level of iron transporter genes in WT, meb2 and transgenic Arabidopsis. Twenty-day-old seedlings of WT, meb2, 35S::BnMEB2/WT and 35S::BnMEB2/meb2 which grown on MS medium were treated with FeSO4 (0.5 mM). AtActin was used as an internal control. (E) The comparison analysis of iron tolerance in Arabidopsis transgenic plants. The seedlings of WT, meb2, 35S::BnMEB2/WT and 35S::BnMEB2/meb2 were cultured on MS agar medium with a series of iron concentration (0.2 mM, 0.3 mM, 0.5 mM, 0.8 mM and 1 mM FeSO4) for 20 days.

The enhanced tolerance of BnMEB2 over-expression plants to iron stress prompts us to evaluate the expression level of other key VIT genes such as AtVIT1, AtNRAMP3 and AtNRAMP4 in all four above lines. It was previously revealed that AtVIT1 functioned as the main transporter allowing iron uptake into vacuoles when exposed to excess iron (Kim et al., 2006). AtNRAMP3 and AtNRAMP4 genes specifically acted as a retriever to export iron from vacuoles when at the deficient iron conditions (Lanquar et al., 2005). The transcription level of AtVIT1,AtNRAMP3 and AtNRAMP4 showed no significant differences among 35S::BnMEB2 transgenic lines and meb2 when compared with wild type plants (Figures 4C,D), while the expression of MEB2 gene was dramatically increased in the 35S::BnMEB2/WT and 35S::BnMEB2/meb2 transgenic plants and strongly suppressed in meb2 (Figure 4A). These results suggested that the enhanced iron tolerance in 35S::BnMEB2/WT and 35S::BnMEB2/meb2 transgenic plants was mainly caused by the high expression of BnMEB2. Over-expression of BnMEB2 restored the iron tolerance ability of meb2 in the complementary lines, indicating that abundant expression of BnMEB2 facilitated the iron storage in plant vacuoles and thus leading to better tolerate the high iron concentration stress. Hence, BnMEB2 plays important roles in the tolerance of high iron concentration stress.

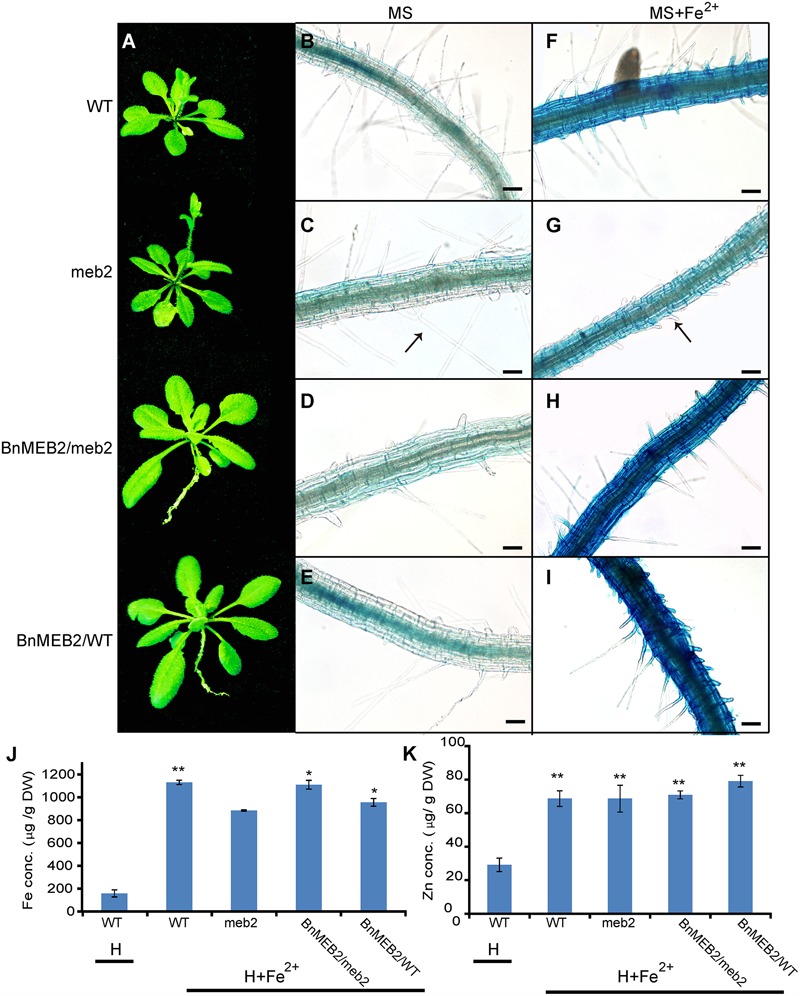

BnMEB2 Increases Plant Detoxification Ability of Iron Stress

To deeply characterize the mechanism of enhanced iron tolerance in BnMEB2 over-expressed Arabidopsis transgenic plants, iron storage in roots of WT, meb2, 35S::BnMEB2/WT and 35S::BnMEB2/meb2 plants were determined by representative Perls’ staining. Iron and zinc contents in these seedlings were also measured by using inductively coupled plasma spectrometry. Under high iron concentration condition (0.5 mM FeSO4), 35S::BnMEB2/WT and 35S::BnMEB2/meb2 transgenic plants showed a better growth status with bigger rosette leaves and developed root system when compared with meb2 (Figure 5A). Iron localization in roots were very similar among WT, meb2 and 35S::BnMEB2/meb2, only a slight higher in 35S::BnMEB2/WT when grown on MS medium (Figures 5B–E). While under the MS medium with 0.5 mM FeSO4 condition, distinct blue staining was observed and became intensified in the roots of WT, 35S::BnMEB2/meb2 and 35S::BnMEB2/WT transgenic plants (Figures 5F–I). However, iron distribution in roots of meb2 had a little alternation between normal and high iron concentration conditions but root hairs elongation was obviously inhibited under iron stress condition (Figures 5C,G). Furthermore, when challenged by high iron concentration treatment, the iron and zinc contents were significantly increased in all types plants when compared with the WT under normal condition (Figures 5J,K). Interestingly, with high iron concentration treatment, iron contents in the seedlings of 35S::BnMEB2/meb2, 35S::BnMEB2/WT transgenic plants and WT were significantly higher than that of meb2 (Figure 5J), but zinc contents in all four seedlings were similar with each other (Figure 5K). These results indicated that over-expression of BnMEB2 increased iron storage in the vacuole of root cells and iron content in the Arabidopsis seedlings in response to high iron concentration stress, resulting in increased detoxification ability in BnMEB2 transgenic plants which ensured the normal growth and development.

FIGURE 5.

The detoxification ability of BnMEB2.(A) Phenotypes of WT, meb2 and transgenic Arabidopsis. Three-week-old seedlings of WT, meb2, 35S::BnMEB2/WT and 35S::BnMEB2/meb2 were grown in 0.5 mM FeSO4 iron nutrient solution (H+Fe2+). (B–I) The iron storage in roots of WT, meb2 and transgenic Arabidopsis by representative Perls’ staining. The seedlings of WT, meb2, 35S::BnMEB2/WT and 35S::BnMEB2/meb2 were grown on MS medium (B–E) and MS medium added with 0.5 mM FeSO4 (G–I) for 10 days. The arrow indicates the root hairs. The bar means 20 μm. (J,K) Iron contents and zinc contents in the seedlings of WT, meb2 and transgenic Arabidopsis. The seedlings of WT, meb2, 35S::BnMEB2/WT and 35S::BnMEB2/meb2 were grown in 0.5 mM FeSO4 iron nutrient solution (H + Fe2+) for 30 days. Another set of the WT seedlings were grown in the normal Hoagland nutrient solution (H) for 30 days. Both sets incubated in the same environment conditions in a growth room. Statistical analysis were performed between WT under the H condition and each of four genotypes under the H + Fe2+ condition. Data are mean ± SD, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01.

Discussion

BnMEB2 Is a Novel Vacuolar Membrane Located VIT Member

Over the past decade, the important biological functions of several VITs in Arabidopsis, rice and other plant species had been characterized as vacuolar sequestration of iron storage, such as AtVIT1, OsVIT1, OsVIT2 and TgVIT1(Kim et al., 2006; Momonoi et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2012). In Arabidopsis, AtVTL1, AtVTL2 and AtVTL5 which showed significant homology to AtVIT1, also catalyzed transportation of iron into vacuoles and thus contributed to the regulation of iron homeostasis in the plant (Gollhofer et al., 2014). Another protein AtMEB2 was a vital member of VIT family, and located on endoplasmic reticulum (ER) body membrane involving in iron homeostasis (Yoshida and Negishi, 2013). In general, proteins containing the conserved iron transportation motif of VIT domain are assigned to the VIT family, being responsible for the regulation of cytosolic iron homeostasis (Yoshida and Negishi, 2013). In this study, we identified a homolog of AtMEB2 in B. napus and assigned as BnMEB2. BnMEB2 also contained a VIT domain in the C-terminal region (Figure 1A). By clustal and phylogenetic analysis, BnMEB2 and BnaA06g26800D shared a high similarity with AtMEB2 and also shared similar 3D structures of VIT domain with AtVIT1 and AtMEB2 (Figures 1B,C; Supplementary Figure S2). Notably, it is peculiar that VIT family members were located on the vacuolar membrane. BnMEB2 also was located on vacuolar membrane (Figures 2A,B), indicating a conservative vacuolar metal transport function for BnMEB2. Therefore, it is reasonable to propose that BnMEB2 is a novel VIT member with underlying ability of metal iron transportation.

BnMEB2 Enhances Iron Tolerance by Participating in Iron Storage for Vacuolar Detoxification in Plant

Incapable for escaping from unwanted changes in the environment, the sessile plants have developed a series of tolerance strategies such as vacuolar sequestration, metal chelation, and metal effluxion to cope with the negative consequences of metal toxicity (Clemens, 2006; Singh et al., 2016). AtMEB2 was involved in the metal ion homeostasis and enhanced iron resistance in yeast ccc1 mutant (Yamada et al., 2013). In B. napus seedlings, expression of BnMEB2 was strongly induced under high iron concentration treatment in both roots and leaves (Figures 3C,D), suggesting that BnMEB2 might play important role in iron homeostasis when plants grew under such conditions. At the stages of germination and growth, over-expression BnMEB2 transgenic seedlings had stronger iron tolerance while the seedlings of meb2 were more sensitive to high iron concentration stress (Figure 4E). The expression of MEB2 gene was dramatically up-regulated while other key VIT genes showed no significant differences among them (Figures 4A–D). These observations lead to the conclusion that the alteration of iron tolerance is closely related to the expression level of BnMEB2.

As far as metal toxicity is concerned, the most important mechanism of metal tolerance in plants is vacuolar detoxification. Although iron can be stored in ferritin protein in chloroplast and mitochondria, vacuolar detoxification serves as a principal and safe strategy in iron storage. In Arabidopsis, only 5% of iron was incorporated in ferritin protein, while vacuoles appear to be the major compartment for iron storage (Ravet et al., 2009). BnMEB2 did not affect the root hair development when grown on MS medium (Figures 5B–E). However, root hair elongation was obviously restrained in meb2 and iron content of meb2 was lower when compared with other seedlings under 0.5 mM FeSO4 condition (Figures 5G,J), suggesting that loss function of MEB2 resulted in iron toxicity of roots cell and affect roots development which in turn to decrease iron acquisition. On the contrary, over-expression BnMEB2 transgenic seedlings were grown and developed normally even if iron distribution and acquisition significantly increased about five folds (Figures 5F–I). Simultaneously, BnMEB2 located on vacuolar membrane (Figure 2) and the expression level of BnMEB2 was critical for iron tolerance, showing that the high expression level of BnMEB2 acted as a vacuolar sequestration of iron storage to detoxify iron stress. Zinc contents in all types of plants increased from about 30–70 μg/g DW (dry weight), while no significant differences were detected among each other under low zinc concentration condition (Figure 5K), indicating that the increasing of one metal ion might activate roots to acquire other divalent metal too which further harden toxic metal stress, such as over-expression of NAS causing to concomitant increasing in iron and zinc content in rice grains (Johnson et al., 2011). Thus, BnMEB2 enhances iron tolerance which significantly plays a role in plants adapting to adverse environment.

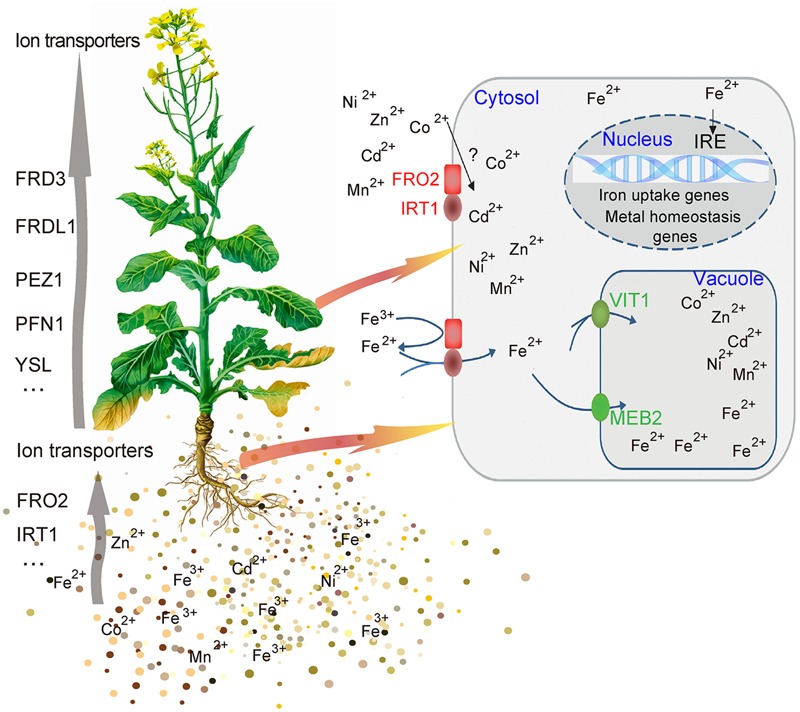

BnMEB2 Sheds a New Light on Homeostasis Regulations in Iron Toxicity and Tolerance

The complex process of iron homeostasis must be highly coordinated by iron uptake, long-distance transport and distribution to different tissues and cell compartments. In the process of iron transport in plant, the VIT members contribute to iron trafficking in vacuoles. Vacuoles are the crucial compartment for storage and detoxification of iron excess and a buffering pool for iron remobilization in periods of iron deficiency. Based on the results above, this study showed that BnMEB2 was involved in high iron tolerance of B. napus. Thus, it is reasonable to propose a model for BnMEB2 regulation in iron homeostasis and enhancing iron tolerance in B. napus, which are partially schematically represented in Figure 6. When challenged by a high level of iron environment, abundant Fe3+ is firstly reduced to more soluble Fe2+ by FRO2 and is acquired into the root cells with poorly selective by membrane transporter IRT1, causing to iron excess and toxic in cytoplasm of cell. The status of iron excess triggers a significant up-regulated expression of iron transporter genes such as BnMEB2. Then, vacuolar membrane located BnMEB2 traffics of iron into the vacuoles for storage and to avoid iron toxicity. Finally, the iron level in cytoplasm rebalances within an optimal physiological range and the plants result in more tolerant to high iron concentration stress. Briefly, BnMEB2 enhances iron tolerance by the vacuolar sequestration and vacuolar detoxification strategy. It provides a new insight on iron homeostasis in the tolerance of high iron concentration stress.

FIGURE 6.

Potential signaling of iron homeostasis. A hypothetical model was shown the mechanism of BnMEB2 enhancing the iron tolerance in Brassica napus.

BnMEB2 Highlights a Potential Strategy for Iron Biofortification and Human Health

With the tremendous rise of industrialization emissions of toxic metals, the increasing serious toxic metal pollution strongly interferes with the crops metabolism, development, and thus productivity and yield (Lutts and Lefèvre, 2015). The VIT members play important roles in maintaining the metal ion availability in the cytosol within an optimal range by appropriate sequestration into or retrieval from the vacuoles. For instance, over-expression of AtPCS1 in tobacco activated high levels of phytochelatin synthesis to increase detoxification capacity to toxic metal stress (Zanella et al., 2016). Over-expression of AtVIT1 increased accumulation of iron in the edible part of storage roots and stems of cassava (Narayanan et al., 2015). This study finds BnMEB2 conservatively localizing on the vacuolar membrane and enhancing tolerance to high iron concentration stress. Therefore, over-expression of BnMEB2 can be applied to minimize the serious threat of metal toxic stress and improve the survival and yield of B. napus and other crops. The current study highlights the significance of BnMEB2 potential application.

Iron is a required micro-nutrient for all living organisms. Iron deficiency anemia is one of the most prevalent micro-nutrient deficiencies in the world, affecting almost 25% of the world population (Clemens et al., 2002; Cvitanich et al., 2010). Thus, increasing iron biofortification in vegetable crops of Brassica family could have a positive significance on human health. In higher plants, to maintain the structural and functional integrity of thylakoid membranes in chloroplasts (Kim and Guerinot, 2007), approximately 90% of iron abundance is required to allocate in the leaves (Terry and Abadía, 1986). When B. napus was challenged by high iron environment, considerable iron amounts were accumulated in stomata guard cells of leaves (Tewari et al., 2013). Meanwhile, in oilseed rape mature leaves, BnMEB2 is highly expressed and can be induced by iron stress which revealed a close relationship between BnMEB2 and iron storage (Figure 3A). In our previous study, Bol022443 and Bra009746, significant homologies to AtMEB2 were identified in B. rapa and B. oleracea respectively. They are highly conserved in evolution and all strongly expressed in leaves by previous trancriptome detection (Tong et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2014), suggesting that MEB2 was involved in iron distribution and storage in Brassicaceae leaves. For Brassica vegetables, their leaves are the main edible source for supplying vitamins, cellulose, minerals and other kinds of nutrition for human health. Study on MEB2 sheds light on a potential strategy for iron biofortification in Brassica crops.

Conclusion

Vacuolar detoxification is the key mechanism to tolerate metal toxic stress in plant cells, which resulted in the removal of toxic ions from sensitive sites to vacuolar compartments by various VIT members (Sharma et al., 2016). Enhanced iron tolerance by vacuolar detoxification is a safe strategy for plant to survive and adapt to adverse environmental conditions. In this research, a novel functional gene BnMEB2 in rapeseed plant was proposed in vacuolar detoxification and iron tolerance. BnMEB2 is a vacuolar membrane located new VIT gene which was highly expressed in mature leaves and can be strongly induced by high iron concentration stress in the roots and leaves. The transcript in level of BnMEB2 is closely related to tolerance of plants under high iron concentration stress. BnMEB2 is the first identified VIT gene in rapeseed with vacuolar detoxification function, acting as a VIT to mediate iron storage into vacuoles to detoxify iron stress and finally enhancing the tolerance to high iron concentration stress. These findings obtained in the study can be useful for the genetic improvement of iron tolerance and improve the nutrition value in Brassica crops breeding.

Author Contributions

WZ, CD, and SL conceived the idea, designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. WZ, RZ, and MT performed the experiments. XC, YL, and YX contributed materials and analysis tools to this work. RFZ, CT, and JH analyzed the data. All the authors approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research is funded by grants from the National Key research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0101007, 2016YFD0100305), Natural High Technology Research and Development Program of China (2013AA102602), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31301039) and supported by Science & technology special project of Guizhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences (no. [2014]014). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2016.01353

The diagram of pUC19-35Spro::GFP vector (A) and 35Spro::BnMEB2::GFP vector (B) which showed detailed information.

Comparison analysis of 3D structure model of VIT domain in AtVIT1, AtMEB2 and BnMEB2. The green, red and blue bands indicate AtVIT1, AtMEB2 and BnMEB2, respectively. (A) BnMEB2 versus AtVIT1; (B) BnMEB2 versus AtMEB2.

References

- Bashir K., Ishimaru Y., Shimo H., Nagasaka S., Fujimoto M., Takanashi H., et al. (2011). The rice mitochondrial iron transporter is essential for plant growth. Nat. Commun. 2 322 10.1038/ncomms1326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briat J. F., Ravet K., Arnaud N., Duc C., Boucherez J., Touraine B., et al. (2010). New insights into ferritin synthesis and function highlight a link between iron homeostasis and oxidative stress in plants. Ann. Bot. 105 811–822. 10.1093/aob/mcp128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassin G., Mari S., Curie C., Briat J. F., Czernic P. (2009). Increased sensitivity to iron deficiency in Arabidopsis thaliana over accumulating nicotianamine. J. Exp. Bot. 60 1249–1259. 10.1093/jxb/erp007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalhoub B., Denoeud F., Liu S., Parkin I. A., Tang H., Wang X., et al. (2014). Early allopolyploid evolution in the post-Neolithic Brassica napus oilseed genome. Science 345 950–953. 10.1126/science.1253435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu H., Chiecko J., Punshon T., Lanzirotti A., Lahner B., Salt D., et al. (2010). Successful reproduction requires the function of Arabidopsis yellow stripe-like1 and yellow stripe-like3 metal-nicotianamine transporters in both vegetative and reproductive structures. Plant Physiol. 154 197–210. 10.1104/pp.110.159103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens S. (2006). Toxic metal accumulation, responses to exposure and mechanisms of tolerance in plants. Biochimie 88 1707–1719. 10.1016/j.biochi.2006.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens S., Palmgren M. G., Krämer U. (2002). A long way ahead: understanding and engineering plant metal accumulation. Trends Plant Sci. 7 309–315. 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02295-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough S. J., Bent A. F. (1998). Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16 735–743. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conte S. S., Walker E. L. (2011). Transporters contributing to iron trafficking in plants. Mol. Plant 4 464–476. 10.1093/mp/ssr015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curie C., Briat J. F. (2003). Iron transport and signaling in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 54 183–206. 10.1007/978-3-642-14369-4_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curie C., Cassin G., Couch D., Divol F., Higuchi K., Le J. M., et al. (2009). Metal movement within the plant: contribution of nicotianamine and yellow stripe 1-like transporters. Ann. Bot. 103 1–11. 10.1093/aob/mcn207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curie C., Panaviene Z., Loulergue C., Dellaporta S. L., Briat J. F., Walker E. L. (2001). Maize yellow stripe1 encodes a membrane protein directly involved in Fe (III) uptake. Nature 409 346–349. 10.1038/35053080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvitanich C., Przybylowicz W. J., Urbanski D. F., Jurkiewicz A. M., Mesjasz P. J., Blair M. W., et al. (2010). Iron and ferritin accumulate in separate cellular locations in phaseolus seeds. BMC Plant Biol. 10:26 10.1186/1471-2229-10-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrett T. P., Gassmann W., Rogers E. E. (2007). The FRD3-mediated efflux of citrate into the root vasculature is necessary for efficient iron translocation. Plant Physiol. 144 197–205. 10.1104/pp.107.097162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duy D., Wanner G., Meda A. R., Wiré N., Soll J., Philippar K. (2007). PIC1, an ancient permease in Arabidopsis chloroplasts, mediates iron transport. Plant Cell 19 986–1006. 10.1105/tpc.106.047407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollhofer J., Timofeev R., Lan P., Schmidt W., Buckhout T. J. (2014). Vacuolar-iron-transporter1-like proteins mediate iron homeostasis in Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE 9:e110468 10.1371/journal.pone.0110468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L. S., Rogers E. E. (2004). FRD3 controls iron localization in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 136 2523–2531. 10.1104/pp.104.045633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guex N., Peitsch M. C. (1997). SWISS-MODEL and the swiss-Pdb viewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18 2714–2723. 10.1002/elps.1150181505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindt M. N., Guerinot M. L. (2012). Getting a sense for signals: regulation of the plant iron deficiency response. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1823 1521–1530. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru Y., Kakei Y., Shimo H., Bashir K., Sato Y., Sato Y., et al. (2011). A rice phenolic efflux transporter is essential for solubilizing precipitated apoplasmic iron in the plant stele. J. Biol. Chem. 286 24649–24655. 10.1074/jbc.M111.221168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru Y., Suzuki M., Tsukamoto T., Suzuki K., Nakazono M., Kobayashi T., et al. (2006). Rice plants take up iron as an Fe3+-phytosiderophore and as Fe2+. Plant J. 45 335–346. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02624.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain A., Connolly E. L. (2013). Mitochondrial iron transport and homeostasis in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 4:348 10.3389/fpls.2013.00348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong J., Guerinot M. L. (2009). Homing in on iron homeostasis in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 14 280–285. 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A. A. T., Kyriacou B., Callahan D. L., Carruthers L., Stangoulis J., Lombi E., et al. (2011). Constitutive over expression of the OsNAS gene family reveals single-gene strategies for effective iron-and zinc-biofortification of rice endosperm. PLoS ONE 6:e24476 10.1371/journal.pone.0024476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. A., Guerinot M. L. (2007). Mining iron: iron uptake and transport in plants. FEBS Lett. 581 2273–2280. 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. A., Punshon T., Lanzirotti A., Li L., Alonso J. M., Ecker J. R., et al. (2006). Localization of iron in Arabidopsis seed requires the vacuolar membrane transporter VIT1. Science 314 1295–1298. 10.1126/science.1132563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T., Nishizawa N. K. (2012). Iron uptake, translocation, and regulation in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 63 131–152. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanquar V., Lelievre F., Bolte S., Hames C., Alcon C., Neumann D., et al. (2005). Mobilization of vacuolar iron by AtNRAMP3 and AtNRAMP4 is essential for seed germination on low iron. EMBO J. 24 4041–4051. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanquar V., Ramos M. S., Lelievre F., Barbier-Brygoo H., Krieger-Liszkay A., Kramer U., et al. (2010). Export of vacuolar manganese by AtNRAMP3 and AtNRAMP4 is required for optimal photosynthesis and growth under manganese deficiency. Plant Physiol. 152 1986–1999. 10.1104/pp.109.150946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Song J. B., Zhao W. T., Yang Z. M. (2013). AtHO1 is involved in iron homeostasis in a no-dependent manner. Plant Cell Physiol. 54 1105–1117. 10.1093/pcp/pct063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Liu Y., Yang X., Tong C., Edwards D., Parkin I. A., et al. (2014). The Brassica oleracea genome reveals the asymmetrical evolution of polyploid genomes. Nat. Commun. 5 3930–3930. 10.1038/ncomms4930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutts S., Lefèvre I. (2015). How can we take advantage of halophyte properties to cope with heavy metal toxicity in salt-affected areas? Ann. Bot. 115 509–528. 10.1093/aob/mcu264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Cózatl D. G., Jobe T. O., Hauser F., Schroeder J. I. (2011). Long-distance transport, vacuolar sequestration, tolerance, and transcriptional responses induced by cadmium and arsenic. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 14 554–562. 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momonoi K., Yoshida K., Mano S., Takahashi H., Nakamori C., Shoji K., et al. (2009). A vacuolar iron transporter in tulip, TgVIT1, is responsible for blue coloration in petal cells through iron accumulation. Plant J. 59 437–447. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03879.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey J., Baxter I. R., Lee J., Li L., Lahner B., Grotz N., et al. (2009). The ferroportin metal efflux proteins function in iron and cobalt homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21 3326–3338. 10.1105/tpc.109.069401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan N., Beyenea G., Chauhana R. D., Solisa E. G., Grusakb M. A., Taylora N., et al. (2015). Over-expression of Arabidopsis VIT1 increases accumulation of iron in cassava roots and stems. Plant Sci. 240 170–181. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J. S., Gong J. M. (2014). Vacuolar sequestration capacity and long-distance metal transport in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 5:19 10.3389/fpls.2014.00019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaldi D., Ciccarelli F. D. (2009). FancyGene: dynamic visualization of gene structures and protein domain architectures on genomic loci. Bioinformatics 25 2281–2282. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravet K., Touraine B., Boucherez J., Briat J. F., Gaymard F., Cellier F. (2009). Ferritins control interaction between iron homeostasis and oxidative stress in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 57 400–412. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03698.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson N. J., Procter C. M., Connolly E. L., Guerinot M. L. (1999). A ferric-chelate reductase for iron uptake from soils. Nature 397 694–697. 10.1038/17800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S. S., Dietz K., Mimura T. (2016). Vacuolar compartmentalization as indispensable component of heavy metal detoxification in plants. Plant Cell Environ. 39 1112–1126. 10.1111/pce.12706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S., Parihar P., Singh R., Singh V. P., Prasad S. M. (2016). Heavy metal tolerance in plants: role of transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and ionomics. Front. Plant Sci. 6:1143 10.3389/fpls.2015.01143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavic K., Krishna S., Lahree A., Bouyer G., Hanson K. K., Vera I., et al. (2016). A vacuolar iron-transporter homologue acts as a detoxifier in Plasmodium. Nat. commun. 7 10403 10.1038/ncomms10403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry N., Abadía J. (1986). Function of iron in chloroplasts. J. Plant Nutr. 9 609–646. 10.1080/01904168609363470 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tewari R. K., Hadacek F., Sassmann S., Lang I. (2013). Iron deprivation-induced reactive oxygen species generation leads to non-autolytic PCD in Brassica napus, leaves. Environ. Exp. Bot. 91 74–83. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2013.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J. (1994). CLUSTALW: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22 4673–4680. 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong C., Wang X., Yu J., Jian W., Li W., Huang J., et al. (2013). Comprehensive analysis of RNA-seq data reveals the complexity of the transcriptome in Brassica rapa. BMC Genomics 14:689 10.1186/1471-2164-14-689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vert G., Grotz N., Dédaldéchamp F., Gaymard F., Guerinot M. L., Briat J. F., et al. (2002). IRT1, an Arabidopsis transporter essential for iron uptake from the soil and for plant growth. Plant Cell 14 1223–1233. 10.1105/tpc.001388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H., Ji Y., Du J., Kong D., Liang H., Ling H. Q. (2010). Clpc1, an ATP-dependent Clp protease in plastids, is involved in iron homeostasis in Arabidopsis leaves. Ann. Bot. 105 823–833. 10.1093/aob/mcq051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie K., Chen J., Wang Q., Yang Y. (2014). Direct phosphorylation and activation of a mitogen-activated protein kinase by a calcium-dependent protein kinase in rice. Plant Cell 26 3077–3089. 10.1105/tpc.114.126441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K., Nagano A. J., Nishina M., Hara-Nishimura I., Nishimura M. (2013). Identification of two novel endoplasmic reticulum body-specific integral membrane proteins. Plant Physiol. 161 108–120. 10.1104/pp.112.207654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokosho K., Yamaji N., Ueno D., Mitani N., Ma J. F. (2009). OsFRDL1 is a citrate transporter required for efficient translocation of iron in rice. Plant Physiol. 149 297–305. 10.1104/pp.108.128132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo S. D., Cho Y. H., Sheen J. (2007). Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts: a versatile cell system for transient gene expression analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2 1565–1572. 10.1038/nprot.2007.199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K., Negishi T. (2013). The identification of a vacuolar iron transporter involved in the blue coloration of cornflower petals. Phytochemistry 94 60–67. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2013.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanella L., Fattorini L., Brunetti P., Roccotiello E., Cornara L., Angeli S., et al. (2016). Over-expression of AtPCS1 in tobacco increases arsenic and arsenic plus cadmium accumulation and detoxification. Planta 243 605–622. 10.1007/s00425-015-2428-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Xu Y. H., Yi H. Y., Gong J. M. (2012). Vacuolar membrane transporters OsVIT1 and OsVIT2 modulate iron translocation between flag leaves and seeds in rice. Plant J. 72 400–410. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05088.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R. F., Yuan W. Z., Tong C. B., Huang J. Y., Cheng X. H., Yu J. Y., et al. (2014). Identification and evolution of VIT gene family between A and C genomes in Brassica. Chin. J. Oil Crop Sci. 36 551–556. 10.7505/j.issn.1007-9084.2014.05.00 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The diagram of pUC19-35Spro::GFP vector (A) and 35Spro::BnMEB2::GFP vector (B) which showed detailed information.

Comparison analysis of 3D structure model of VIT domain in AtVIT1, AtMEB2 and BnMEB2. The green, red and blue bands indicate AtVIT1, AtMEB2 and BnMEB2, respectively. (A) BnMEB2 versus AtVIT1; (B) BnMEB2 versus AtMEB2.