Abstract

Objectives

With the developments of near-cures for hepatitis C virus (HCV), who to screen has become a high-priority policy issue in many western countries. Cost-effectiveness of screening programmes should be one consideration when developing policy. The objective of this work is to synthesise the cost-effectiveness of HCV screening programmes.

Setting

A systematic review was completed. 5 databases were searched until May 2016 (NHSEED, MEDLINE, the HTA Health Technology Assessment Database, EMBASE, EconLit).

Participants

Any study reporting an economic evaluation (any type) of screening compared with opportunistic or no screening for HCV was included. Exclusion criteria were: (1) abstracts or commentaries, (2) economic evaluations of other interventions for HCV, including blood donors screening, diagnosis tests for HCV, screening for concurrent disease or medications for treatment.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Data extraction included type of model, target population, perspective, comparators, time horizon, discount rate, clinical inputs, cost inputs and outcome. Quality was evaluated using the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards checklist. Data are summarised using narrative synthesis by population.

Results

2305 abstracts were identified with 52 undergoing full-text review. 30 papers met inclusion criteria addressing 7 populations: drug users (n=6), high risk (n=5), pregnant (n=4), prison (n=3), birth cohort (n=8), general population (n=5) and other (n=6). The majority (77%) of the studies were high quality. Drug users, birth cohort and high-risk populations were associated with cost-effectiveness ratios of under £30 000 per quality-adjusted-life-year (QALY). The remaining populations were associated with cost-effectiveness ratios that exceeded £30 000 per QALY.

Conclusions

Economic evidence for screening populations is robust. If a cost per QALY of £30 000 is considered reasonable value for money, then screening birth cohorts, drug users and high-risk populations are policy options that should be considered.

Keywords: Hepatitis C Virus, Screening Program

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This research determines the breadth and range of cost-effectiveness estimates, as well as the gaps in knowledge, for hepatitis C virus screening programmes.

This research provides knowledge to support evidence-informed policy that includes consideration of value for money.

Cost analyses would likely not account for all currently available drugs such as simeprevir and sofosibvir.

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV)1 is transmitted through exposure to infected blood. Owing to the asymptomatic nature of HCV, infected individuals often remain undiagnosed until they test positive for HCV through opportunistic screening (eg, screening blood donors), or when high alanine aminotransferase levels are detected during routine blood work.2 3 The development of direct acting antivirals (DAAs) has changed the treatment landscape. In comparison to PEG-INF or RBV-based treatments, DAAs have been found to have higher cure rates (90–100% viral clearance rates at 12 weeks) and virtually no side effects.4

Within this new paradigm, many countries are reassessing their approach to HCV identification and management. In addition, with the emergence of new treatments with greater success rates and less side effects, identifying HCV earlier has become a focus of public health programmes. The clinical effectiveness of HCV screening programmes has been synthesised by agencies such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Public Health Agency of Canada. As a result, the WHO5 and the Center for Disease Control6 have recommended and promoted the implementation of HCV screening programmes. In addition, these new drugs are currently priced at ∼$C1000 per pill, equating to £35 000 per 12-week course of treatment. The cost-effectiveness of any screening programme within this new treatment paradigm will need to be carefully considered. Thus, the objective of this study was to synthesise the economic evaluations of HCV screening programmes. This research will determine the breadth and range of cost-effectiveness estimates, as well as the gaps in knowledge, for HCV screening programmes. This is required knowledge to support evidence-informed policy that includes consideration of value for money.

Materials and methods

A systematic review was performed to identify economic evaluations that assess HCV screening. Five databases were searched from inception until 19 May 2016: NHSEED, MEDLINE, the HTA Health Technology Assessment Database, EMBASE, EconLit. Variations of the terms ‘Hepatitis C’, ‘Screening’ and ‘Economic Evaluation’ were combined. Details of the search strategy are available in online supplementary appendix A. Studies were limited to humans, and those available in the English language. Abstracts were screened in duplicate and any selected by either reviewer proceeded to full-text review. The inclusion criteria were: economic evaluation (cost minimisation, cost-effectiveness, cost utility and cost benefit), population or risk subgroup screening for HCV, or comparison to opportunistic screening (ie, an individual is accessing healthcare for an alternate reason), high-risk group or no formal programme. Studies were excluded if they were abstracts or commentaries, or if they were economic evaluations of blood donor testing, tests for diagnosing HCV (ie, PCR vs antibody), screening for HCV coinfection (ie, HCV and HIV) versus HCV alone, or medications for treating HCV. The full-text review was also performed in duplicate and any studies that met the inclusion or failed to meet the exclusion criteria then proceeded to data extraction. Any discrepancies during duplicate review were addressed with consultation until consensus was reached. The bibliographies of the included studies and related prior systematic reviews were hand-searched to ensure that all relevant papers were captured in the literature search.

bmjopen-2016-011821supp_appendixes.pdf (422.8KB, pdf)

Studies were stratified into seven categories based on the target population of the screening intervention: Intravenous Drug Users (IVDU), High Risk (as defined by the author), Prisoners, Pregnant Women, Birth Cohort, General Population, other populations (do not fall into any of the aforementioned categories). Studies that assessed more than one type of screening intervention were stratified and included in all appropriate categories. For example, a cost-utility model comparing general screening and birth-cohort screening interventions with no screening intervention was included in the general population and birth cohort screening interventions. Any population screening that did not coincide with the first six categories was included in the ‘other’ category.

The following data were extracted in duplicate: year of publication; country; populations who were screened; type of model; perspective; comparators; model details such as time horizon and discount rate; outcome(s) assessed and currency. Discrepancies between reviewers during data extraction were resolved through consensus. All costs were converted to Great British Pounds (£) using the exchange rate for each initial currency. The quality of the study was assessed with the Consensus Health Economic Criteria (CHEC) list.7 The checklist includes 24 recommended items (eg, title, choice of health outcomes, measurement of effectiveness), and a point was allocated if the study included that item (see online supplementary appendix B). The studies were then deemed high quality if they score >20 points, average quality if 17–20 and poor quality if <11.

Patient involvement

No patients were directly involved in this systematic review. However, cost-utility studies use preference-based measures (ie, utilities) which incorporate the patient perspective and enable it to be considered in the value-proposition of the decision-making process.

Results

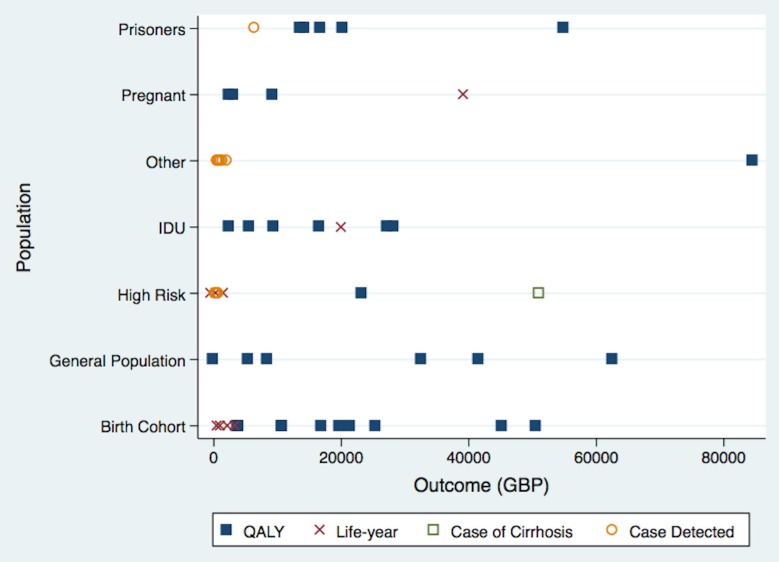

The literature search identified 2305 abstracts, and 52 proceeded to full-text review. After full-text review, a further 22 articles were excluded: 12 were not economic evaluations, 5 did not assess HCV screening programmes and 5 evaluated HCV tests and not screening programmes. Two systematic reviews, one that evaluated interventions for high-risk groups and the other screening for HCV and hepatitis B, were hand-searched and resulted in no additional publications.8 9 A final 30 papers underwent data extraction; summarised characteristics of studies are presented in table 1, figure 1 and online supplementary appendices C and D. Studies were categorised by target population: drug users (n=6), high risk (n=5), pregnant (n=4), prison (n=3), birth cohort (n=8), general population (n=5) and other (n=6).

Table 1.

Summary of included studies

| Population | n | Dates | Countries | Perspective | Quality | Range of findings | Source of variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug users | 6 | 1999–2012 | UK, USA | 4 payer; 1 societal; 1 not reported | High | £2333 to £28 120 per QALY gained £20 084 per LY gained |

Prevalence, acceptance of treatment |

| High risk | 5 | 1998–2014 | UK,USA | 3 payer; 1 societal; 1 not reported | High/low | £245 to £50 947 per case detected −£514 to £1576 per LY gained |

Prevalence, acceptance of treatment |

| Pregnant women | 4 | 2004–2015 | UK, USA, NETH | All payer | High | £2400 to £802 984 per QALY gained £35 140 to £39 138 per LY gained |

Target population |

| Prisoners | 3 | 2004–2016 | UK, USA | 2 payer; 1 societal | High | £6388 per case found £13 599 to £54 852 per QALY gained |

Acceptance of screening and treatment |

| Birth cohort | 8 | 2008–2013 | USA, ITA, JPN, CAN | 5 payer; 3 societal | High | £3706 to £45 123 per QALY gained £582 to £3311 per LY gained |

Prevalence, uptake |

| General Pop'n | 5 | 2001–2013 | USA, NETH | 2 payer; 3 societal | High | −£66.5 to £62 452 per QALY gained | Prevalence |

| Other | 4 | STD clinic history of gastroscopy, contact with an infected person, history of invasive procedure, history of colonoscopy or history of surgery presenting to emergency department and having blood drawn attending genito-urinary clinic recently deployed military personnel Individuals who had minor or major surgery |

|||||

Figure 1.

Summary of the cost per each outcome type by population. 3 data-points removed as extreme outliers >£600 000 per outcome gained (one study from pregnant population and another from the other population) or reported total cost. *Studies could be captured more than once in figure, if more than one comparator was reported.

Drug users

All of the studies were cost-utility analyses (CUA); all reported a cost per quality-adjusted-life-year (QALY) gained10–15 (table 1, figure 1 and online supplementary appendix C). One study added a cost-effectiveness analysis, which reported life years gained.10 They all used similar analysis, time horizons, comparators and clinical pathways (table 1 and online supplementary appendix C). The six included studies found incremental costs per QALY gained ranging from £233315 to £28 12014 when comparing HCV screening programmes with no screening programme (table 1 and figure 1); with the one additional cost-effectiveness analysis showing £20 084 per life year.10 The six studies were of high quality when evaluated with the CHEC list,7 and none had major flaws10–15 (see online supplementary appendix D). There were no common sources of uncertainty, around the inputs, for these studies, as it covered the range of inputs regarding acceptability of testing and treatment, to the utilities used within the models (see online supplementary appendix C).

High-risk individuals

High risk was as defined by each author, and did not necessarily fall into the ‘drug user’ screening programme category, but could include individuals who had prior blood transfusions. Three of these studies were cost-effectiveness analyses (CEA),16–18 and two were CUA19 20 (table 1, figure 1 and online supplementary appendix C). Overall, these studies were methodologically different as they used varying economic evaluations, outcome measures and time horizons (table 1 and online supplementary appendix C). The two studies that reported cost per case had a range of costs from £24517 to £50 94716 per case found (table 1 and figure 1). One CUA did not report a final cost per QALY gained; however, the authors concluded that screening was not good value for money.19 The other CUA reported ₤23 200 per QALY.20 The remaining studies evaluated four separate high-risk groups and found a range of cost per life year gained from −£514 to £1576 (table 1 and figure 1). Three of the five studies were high quality when evaluated with the CHEC list,7 18–20 one was of average quality16 and the other was poor17 (see online supplementary appendix D). There were fewer areas of uncertainty within this cohort, mainly aimed at the initial prevalence, and screening for HCV (see online supplementary appendix C).

Pregnant woman

One of these studies evaluated screening in two separate pregnant populations (a general pregnant population and a first-generation non-western pregnant population); we have reported the results of this study separately.21 One of the CUAs assessed the lifetime of the pregnant woman and infant,22 the other CUA assessed only the mother23 and the remaining study was a CEA only assessing pregnant women21 (table 1, figure 1 and online supplementary appendix C). The CUA, which assessed a general pregnant population and the lifetime of the infant, found that HCV screening compared with no screening cost £802 984 per QALY gained; specifically for the infant screening and treatment had an ICER of ₤7039 per QALY and the addition of a Caesarean section to every woman had an ICER of ₤2125 per QALY22 (table 1 and figure 1). The other CUA, evaluating only pregnant women, identified three separate scenarios and found ₤2400 per QALY for RBV only, ₤9139 per QALY for Sofosbuvir only and ₤3105 per QALY for RBV then Sofosbuvir.23 The CEA, which also assessed a general pregnant population, found that HCV screening compared with no screening cost £39 138 per life year gained21 (table 1 and figure 1). In comparison, this same study found that for a population of first-generation non-western pregnant women, HCV screening compared with no screening cost £35 140 per life-year gained (table 1 and figure 1). All studies were high quality when evaluated with the CHEC list,7 and had no major flaws (see online supplementary appendix D). The only areas of uncertainty surrounded the discount rates, and utilities (see online supplementary appendix C).

Prisoners

Three of the included studies evaluated HCV screening of prisoners compared with no screening;24–26 one was a CEA,24 and the other two were CUA25 26 (table 1, figure 1 and online supplementary appendix C). The CEA was only case finding, while the CUAs included treatment; they all evaluated prisoners on reception into prison, but one of the CUAs assessed screening all individuals already in prison (table 1 and online supplementary appendix C). The study that did not include treatment costs (only looked at screening methods) found a cost of £6388 per case found24 (table 1 and figure 1). The study that evaluated screening prisoners on reception into prison, and then subsequent treatment, found that HCV screening, compared with no screening cost £54 852 per QALY gained25 (table 1 and figure 1). While the inclusion of screening the population already in prison, aside from those already incarcerated, had a range from £14 178 per QALY gained for 1 year to £20 240 per QALY gained for a 10-year program.26 All studies were assessed as being high quality when evaluated with the CHEC list7 and none had major flaws24 25 (see online supplementary appendix D). These studies noted uncertainty around uptake of testing, progression, discounting and utilities (see online supplementary appendix C).

Birth cohorts

Eight studies evaluated HCV screening compared with no screening for a birth cohort population.18 19 27–32 Six of these studies were CUA,19 27 28 30–32 one was a CEA18 and one study performed a CUA and a CEA29 (table 1, figure 1 and online supplementary appendix C). The seven cost-utility studies18 19 27–32 found that HCV screening ranged from £3706 incremental cost per QALY gained27 to £45 123 incremental cost per QALY gained19 when compared with no screening programme (table 1 and figure 1). The cost-effectiveness study reported a range of £582 per life year gained to £3311 per life year gained18 (table 1 and figure 1). The study which found a cost of £45 123 per QALY gained used universal triple therapy as treatment, which increased cost of treatment19 (table 1 and figure 1). In addition to this, Rein et al30 used multiple treatment arms; when DAAs were added to their base CUA, £50 462 cost per QALY gained was reported (table 1 and figure 1). These two studies demonstrate that the biggest cost driver, and a variable which can change the conclusions of a model, is the treatment choice19 30 (see online supplementary appendix C). When evaluated with the CHEC7 list, all eight studies were of high quality18 19 27–33 (see online supplementary appendix D).

General population

All five studies are CUA, and all reported results using a cost per QALY gained11 27 34–36 (table 1, figure 1 and online supplementary appendix C). One study performed two separate analysis of screening procedures with the same population,11 and another evaluated two separate testing strategies (ELISA then PCR, and only PCR)35 (table 1 and online supplementary appendix C). The results attained by these five studies ranged from −£66.5 per QALY gained36 to £62 452 per QALY gained35 (table 1 and figure 1). One of these studies performed an additional analysis evaluating a general campaign to screen people, and did not find it to be more effective than no screening11 (table 1). The study evaluating ELISA then PCR and only PCR testing versus no screening, and both strategies resulted in costs per QALY gained higher than the WTP threshold; ELISA then PCR £41 520 per QALY gained, and PCR £62 452 per QALY gained35 (table 1, figure 1 and online supplementary appendix C). All of the studies were of high quality when evaluated with the CHEC list7 11 27 34–36 (see online supplementary appendix D).

Other populations

Six of the included studies did not fit into any of the above screening categories.13 15 37–40 One looked at individuals presenting to a sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinic37 (table 1 and online supplementary appendix C). Another evaluated those who had a history of gastroscopy, contact with an infected person, history of invasive procedure, history of colonoscopy or history of surgery38 (table 1 and online supplementary appendix C). The remaining assessed those who presented at a genito-urinary clinic,13 recently deployed military personnel,39 patients who presented to the emergency room and had blood drawn40 and individuals who had minor or major surgery15 (table 1 and online supplementary appendix C). Three of the six studies used the outcome of cost per positive test,37 38 40 two used a cost per QALY gained13 15 and the remaining study calculated total costs39 (table 1, figure 1 and online supplementary appendix C). The results for the studies that evaluated the costs per positive test ranged from £37 per positive test to £2045 per positive test, these came from the same study and were from the intravenous drug users and women over 40, respectively37 (table 1 and figure 1). The two studies that evaluated the cost per QALY gained and ranged from £84 570 per QALY gained40 to £685 754 cost per QALY gained;15 these two studies used a WTP threshold of £30 000 per QALY gained (table 1 and figure 1). Two of the six studies were high quality when evaluated with the CHEC list,7 13 15 one was of average quality,39 the remaining three were poor quality37 38 40 (online supplementary appendix D).

Discussion

The studies performed regarding screening for HCV are generally of good quality and a robust body of evidence has developed. Generally, screening drug users, birth cohorts, high-risk populations and the general population appear to be good value for money if a cost per QALY of £30 000 is used as the threshold for reasonable value. The current evidence suggests screening programmes may not be good value for money in high-risk groups and pregnant women, although the evidence is heterogeneous focusing on a variety of populations and economic outcomes. Surprisingly, screening programmes for prisoners appears not to be good value for money. A variety of other screening programmes have been assessed in the literature targeting genito-urinary clinics, individuals who had minor or major surgery, patients presenting to the emergency room, recently deployed military, those with the history of gastroscopy and visitors to public STD clinics. None of these programmes appear to be good value for money.

Recently, a study evaluating economic evaluations of hepatitis B and HCV evaluating screening and testing strategies was performed.41 The focus of our study was to assess the cost-effectiveness of only screening programmes. Further, our study was able to attain the most recent studies and also divided the studies based on population studied; this allows stakeholders to better evaluate the applicable studies based on population. Each of these populations is a unique group that have different challenges for screening programmes. Therefore, through summarising the studies by screened population, we are able to gain a better summary of the cost-effectiveness of these screening programmes and the variation seen within each group.

Several variables affected the findings of the reported economic evaluations, in particular, the prevalence of asymptomatic HCV, the acceptability of screening and the acceptability of treatment. Of these, prevalence has the largest impact on the outcomes of the economic evaluations. In general, one would expect the cost-effectiveness of screening to be inversely correlated to prevalence; the higher the prevalence in the targeted group, the lower the cost per QALY as more cases would be identified per person screened. Our synthesis supports this finding with data that demonstrates screening populations with higher prevalence of HCV (ie, drug users) generally resulting in better value for money.

However, there is little information about how prevalence, the acceptability of screening and the acceptability of treatment may drive the required implementation plans.

The expected budget impact remains unknown and would be substantially impacted by the proposed implementation plan. A thorough budget impact analysis, particularly for the large birth cohort and general population screening programmes where the overall cost may be large, must be completed.

Limitations

While this systematic review includes robust studies with good quality, several limitations should be considered. The systematic review is limited by the available data in the literature. The results may not be generalisable to all jurisdictions; for example, only one cost-utility analysis has been conducted in Canada and this study only evaluated a birth cohort. Cost analyses differed by time periods that would not have accounted for all currently available drugs such as simeprevir and sofosibvir. Further, none of the studies addressed the implementation of a screening programme and the costs associated with it, which is paramount in choosing the appropriate screening programme.

Conclusion

Screening birth cohorts, drug users and high-risk populations would be good value for money, and should be evaluated as a possibility for implementation. Further evaluations need to be performed regarding the best methods for implementation, with subsequent budget impact analysis.

Footnotes

Contributors: SC contributes to part of design of the work, analysis (retrieve data from papers) and interpretation of data (summarised the final findings); drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version published; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. LL contributes to part of design of the work, the acquisition (run searches), analysis (retrieve data from papers); revising the work critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version published; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. GGK contributes to part of design of the work, and interpretation of data (assessed overall findings of the multiple studies, provided clinical opinion); revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version published; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. FC contributes to part of design of the work, and interpretation of data (assessed overall findings of the multiple studies, provided policy opinion); revising the work critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version published; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: FC is supported by a Harkness/Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement Fellowship in Healthcare Policy and Practice. SC is supported by an Eyes High Doctoral Recruitment Scholarship.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data are from published literature. No unpublished data are contained in this study. Search strategies are included in online supplementary appendix.

References

- 1.Health. Public health notifiable disease management guidelines: hepatitis C (acute case) 2013. http://www.health.alberta.ca/documents/Guidelines-Hepatitis-C-Acute-Case-2013.pdf

- 2.Prevention CfDCa. Hepatitis C FAQS for health professionals 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/hcvfaq.htm—b7

- 3.Canada PHAo. A renewed public health response to address hepatitis C 2009. http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2010/aspc-phac/HP40-44-2009-eng.pdf

- 4.Asselah T, Marcellin P. Interferon free therapy with direct acting antivirals for HCV. Liver Int 2013;33:93–104. 10.1111/liv.12076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caballeria L, Pera G, Bernad J et al. Strategies for the detection of hepatitis C viral infection in the general population. Rev Clin Esp (Barc) 2014;214:242–6. 10.1016/j.rce.2014.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Testing recommendations for hepatitis C virus infection 2014. (cited 10 September 2014). http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/guidelinesc.htm

- 7.Evers S, Goossens M, de Vet H et al. Criteria list for assessment of methodological quality of economic evaluations: consensus on Health Economic Criteria. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2005;21:240–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hahne SJ, Veldhuijzen IK, Wiessing L et al. Infection with hepatitis B and C virus in Europe: a systematic review of prevalence and cost-effectiveness of screening. BMC Infect Dis 2013;13:181 10.1186/1471-2334-13-181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.John-Baptiste A, Yeung MW, Leung V et al. Cost effectiveness of hepatitis C-related interventions targeting substance users and other high-risk groups: a systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics 2012;30:1015–34. 10.2165/11597660-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castelnuovo E, Thompson-Coon J, Pitt M et al. The cost-effectiveness of testing for hepatitis C in former injecting drug users. Health Technol Assess 2006;10:iii–iv, ix–xii, 1–93 10.3310/hta10320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helsper CW, Borkent-Raven BA, de Wit NJ et al. Cost-effectiveness of targeted screening for hepatitis C in The Netherlands. Epidemiol Infect 2012;140:58–69. 10.1017/S0950268811000112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leal P, Stein K, Rosenberg W. What is the cost utility of screening for hepatitis C virus (HCV) in intravenous drug users? J Med Screen 1999;6:124–31. 10.1136/jms.6.3.124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stein K, Dalziel K, Walker A et al. Screening for hepatitis C in genito-urinary medicine clinics: a cost utility analysis. J Hepatol 2003;39:814–25. 10.1016/S0168-8278(03)00392-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stein K, Dalziel K, Walker A et al. Screening for Hepatitis C in injecting drug users: a cost utility analysis. J Public Health (Oxf) 2004;26:61–71. 10.1093/pubmed/fdh109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tramarin A, Gennaro N, Compostella FA et al. HCV screening to enable early treatment of hepatitis C: a mathematical model to analyse costs and outcomes in two populations. Curr Pharm Des 2008;14:1655–60. 10.2174/138161208784746833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Batra N. Hepatitis C screening and treatment versus liver transplantation: a financial option appraisal and commissioning model for purchasers. Disease Management and Health Outcomes 2001;9:371–84. 10.2165/00115677-200109070-00003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lapane KL, Jakiche AF, Sugano D et al. Hepatitis C infection risk analysis: who should be screened? Comparison of multiple screening strategies based on the National Hepatitis Surveillance Program. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:591–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakamura J, Terajima K, Aoyagi Y et al. Cost-effectiveness of the national screening program for hepatitis C virus in the general population and the high-risk groups. Tohoku J Exp Med 2008;215:33–42. 10.1620/tjem.215.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu S, Cipriano LE, Holodniy M et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of risk-factor guided and birth-cohort screening for chronic hepatitis C infection in the United States. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e58975 10.1371/journal.pone.0058975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miners AH, Martin NK, Ghosh A et al. Assessing the cost-effectiveness of finding cases of hepatitis C infection in UK migrant populations and the value of further research. J Viral Hepat 2014;21:616–23. 10.1111/jvh.12190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Urbanus AT, van Keep M, Matser AA et al. Is adding HCV screening to the antenatal national screening program in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, cost-effective? PLoS ONE 2013;8:e70319 10.1371/journal.pone.0070319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plunkett BA, Grobman WA. Routine hepatitis C virus screening in pregnancy: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;192:1153–61. 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.10.600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Selvapatt N, Ward T, Bailey H et al. Is antenatal screening for hepatitis C virus cost-effective? A decade's experience at a London centre. J Hepatol 2015;63:797–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sutton AJ, Edmunds WJ, Gill ON. Estimating the cost-effectiveness of detecting cases of chronic hepatitis C infection on reception into prison. BMC Public Health 2006;6:170 10.1186/1471-2458-6-170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sutton AJ, Edmunds WJ, Sweeting MJ et al. The cost-effectiveness of screening and treatment for hepatitis C in prisons in England and Wales: a cost-utility analysis. J Viral Hepat 2008;15:797–808. 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2008.01008.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He T, Li K, Roberts MS et al. Prevention of hepatitis C by screening and treatment in U.S. Prisons. Ann Intern Med 2016; 164:84–92. 10.7326/M15-0617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coffin PO, Scott JD, Golden MR et al. Cost-effectiveness and population outcomes of general population screening for hepatitis C. Clin Infect Dis 2012;54:1259–71. 10.1093/cid/cis011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McEwan P, Ward T, Yuan Y et al. The impact of timing and prioritization on the cost-effectiveness of birth cohort testing and treatment for hepatitis C virus in the United States. Hepatology 2013;58:54–64. 10.1002/hep.26304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGarry LJ, Pawar VS, Panchmatia HR et al. Economic model of a birth cohort screening program for hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2012;55:1344–55. 10.1002/hep.25510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rein DB, Smith BD, Wittenborn JS et al. The cost-effectiveness of birth-cohort screening for hepatitis C antibody in U.S. primary care settings. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:263–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruggeri M, Coretti S, Gasbarrini A et al. Economic assessment of an anti-HCV screening program in Italy. Value Health 2013;16:965–72. 10.1016/j.jval.2013.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong WW, Tu HA, Feld JJ et al. Cost-effectiveness of screening for hepatitis C in Canada. CMAJ 2015;187:E110–21. 10.1503/cmaj.140711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. BMC Med 2013;11:80 10.1186/1741-7015-11-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eckman MH, Talal AH, Gordon SC et al. Cost-effectiveness of screening for chronic hepatitis C infection in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2013;56:1382–93. 10.1093/cid/cit069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singer ME, Younossi ZM. Cost effectiveness of screening for hepatitis C virus in asymptomatic, average-risk adults. Am J Med 2001;111:614–21. 10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00951-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim DD, Hutton DW, Raouf AA et al. Cost-effectiveness model for hepatitis C screening and treatment: implications for Egypt and other countries with high prevalence. Glob Public Health 2015;10:296–317. 10.1080/17441692.2014.984742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Honeycutt AA, Harris JL, Khavjou O et al. The costs and impacts of testing for hepatitis C virus antibody in public STD clinics. Public Health Rep 2007;122(Suppl. 2):55–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Josset V, Torre JP, Tavolacci MP et al. Efficiency of hepatitis C virus screening strategies in general practice. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2004;28:351–7. 10.1016/S0399-8320(04)94935-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brett-Major DM, Frick KD, Malia JA et al. Costs and consequences: hepatitis C seroprevalence in the military and its impact on potential screening strategies. Hepatology 2016;63:398–407. 10.1002/hep.28303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Orkin C, Flanagan S, Wallis E et al. Incorporating HIV/hepatitis B virus/hepatitis C virus combined testing into routine blood tests in nine UK Emergency Departments: the ‘Going Viral’ campaign. HIV Med 2016;17:222–30. 10.1111/hiv.12364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Geue C, Wu O, Xin Y et al. Cost-effectiveness of HBV and HCV screening strategies—a systematic review of existing modelling techniques. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0145022 10.1371/journal.pone.0145022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-011821supp_appendixes.pdf (422.8KB, pdf)