Abstract

Objectives

Many countries are facing provider shortages and imbalances in primary care or are projecting shortfalls for the future, triggered by the rise in chronic diseases and multimorbidity. In order to assess the potential of nurse practitioners (NPs) in expanding access, we analysed the size, annual growth (2005–2015) and the extent of advanced practice of NPs in 6 Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries.

Design

Cross-country data analysis of national nursing registries, regulatory bodies, statistical offices data as well as OECD health workforce and population data, plus literature scoping review.

Setting/participants

NP and physician workforces in 6 OECD countries (Australia, Canada, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand and USA).

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The main outcomes were the absolute and relative number of NPs per 100 000 population compared with the nursing and physician workforces, the compound annual growth rates, annual and median percentage changes from 2005 to 2015 and a synthesis of the literature on the extent of advanced clinical practice measured by physician substitution effect.

Results

The USA showed the highest absolute number of NPs and rate per population (40.5 per 100 000 population), followed by the Netherlands (12.6), Canada (9.8), Australia (4.4), and Ireland and New Zealand (3.1, respectively). Annual growth rates were high in all countries, ranging from annual compound rates of 6.1% in the USA to 27.8% in the Netherlands. Growth rates were between three and nine times higher compared with physicians. Finally, the empirical studies emanating from the literature scoping review suggested that NPs are able to provide 67–93% of all primary care services, yet, based on limited evidence.

Conclusions

NPs are a rapidly growing workforce with high levels of advanced practice potential in primary care. Workforce monitoring based on accurate data is critical to inform educational capacity and workforce planning.

Keywords: nursing, health workforce, physicians, PRIMARY CARE, nurse practitioner

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study determines the total and relative size of nurse practitioners (NPs) per 100 000 population and growth rates in comparison to physicians in six Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries.

A strength of this study is the analysis of comprehensive and largely unexplored data from authoritative sources in the six countries.

Annual growth rates were calculated for 2005–2015 using compound annual growth rates, annual; and median percentage change to account for excessive yearly changes found.

The study faces limitations as to accuracy of data and data variability of the activity levels of NPs and physicians, yet, for within-country comparisons, we used consistently the same activity levels for NPs and physicians.

The few empirical studies on the substitution effect of NPs for physicians show that NPs can work at high levels of advanced practice; however, future research is necessary to validate the findings.

Background

Health workforce shortages and geographical imbalances exist in many countries worldwide.1 The need for primary care providers is increasing in response to the intensifying healthcare needs of their populations, triggered by the increasing rates of patients with chronic conditions and multimorbidity.2 3 While educating more physicians is one workforce strategy, countries are also investing increasingly in a highly qualified nursing workforce, such as nurse practitioners and other advanced practice nurses (NPs/APNs), with usually Master's level education.4 Expanding the roles of nurses combined with task shifting from physicians to nurses as suggested by the WHO, has received policy attention to respond to shortages, long waiting times and high care needs of patients with chronic conditions.5 6

There is a consistent body of evidence showing that nurses with advanced education can provide high-quality care that is comparable to physicians for a range of acute and chronic illnesses.7–10 The USA was the first country to introduce NPs in 1965 (in Colorado), followed by Canada in 1967 (in Nova Scotia).11 12 NP practice regulations have since been instituted and managed at the subnational level in these countries. Other countries have recently introduced NPs, including the UK, Ireland, the Netherlands, Australia and New Zealand.13–17

The extent to which NPs are effective in addressing shortages and the intensifying care needs of patients with chronic conditions depends on the scale of this workforce, and its integration and implementation in healthcare.18 Scale in this context refers to two factors, sufficient numbers of NPs and their extent of advanced practice. Both elements are critical to assess the contribution of the workforce.

Existing international research on the size of the NP workforce is limited. The international literature has compared primarily NP education, governance and regulation of titles.19–23 In an overview of the primary care workforce in six countries, the total number of NPs was found to be low in most countries.24 However, the study only provided the total number of providers, and no further information on its relative size compared with other professions or time trends. A 2010 Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) report found the NP workforce to be the largest in the USA in absolute and relative size compared with the total nursing workforce, followed by Canada, Australia and Ireland.20 Yet, the report did not differentiate between activity levels and dates back to 2010. It did not provide data on time trends. At the individual country levels, many studies exist, particularly in the USA that aim to quantify the total number of NPs, by employment, specialty and clinical practice area.25–28 They found that the various data sources provide a patchy overview in the USA, particularly when focusing on the clinically active NPs and specific specialty areas.25 The comparatively fewer studies analysing the size of NPs in Canada, Australia and New Zealand found that the workforce is small, but provided limited information beyond the number of providers.29 30

While NPs perform a substantially expanded range of clinical services, there is limited knowledge on the detailed level of advanced practice. The 2010 OECD report provides information on the typical tasks and activities provided by NPs in Australia, Canada, Ireland, the UK and the USA suggesting that NPs provide a large range of services at the interface with the medical profession.20 Conceptually, the substitution effect of physicians by NPs refers to the quantification of how many patients or services in a particular care setting can be performed by NPs that are usually provided by physicians.31 32 In a systematic review, 30–70% of clinical activities of physicians were found could be taken over by NPs or other non-physician providers; however, most of the included studies were conducted in the 1970s and 1980s and included a wide range of non-physician providers, including NPs, other nursing roles and physician assistants.31 NPs' roles have expanded internationally, hence a review focused on NPs only, providing an update of the literature, is relevant to synthesise the evidence on the extent of advanced practice and variations across countries.

This study pursued the following three research objectives: (1) to analyse the absolute and relative size of the NP workforce in six OECD countries (Australia, Canada, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand and the USA), focusing on practising NPs, their proportion of the total nursing workforce and rates per 100 000 population relative to the physician workforce; (2) to examine time trends from 2005 to 2015 in the NP compared with the physician workforces; and (3) to synthesise the evidence on the extent of advanced practice in primary care referred to as physician ‘substitution effect’.

The three objectives are separate, but inter-related: all three parameters (size, growth, per cent of physician substitution) are critical for workforce planning and projections.33 Data on the three parameters provide the numerical basis in order to forecast the current and future potential of NPs in addressing the expected growing demand and intensifying healthcare needs.

Methods

Definitions and outcome measures

In order to assess the absolute and relative size of the NP workforce, we followed the OECD definition of activity levels of health professions: (1) practising professionals (providing direct patient care), (2) professionally active (providing direct patient care, plus working in related administration, management or research as part of the profession) and (3) registered/licensed to practice (authorised to practice, including practising, professionally active and non-practising providers).34 For this study, the activity status practising NPs was preferred over professionally active and registered/licensed, following the OECD.34 In countries with no available information on the number of practising NPs, data on professionally active or registered providers were used.

To analyse time trends, we compared the yearly growth rates of NPs to physicians from 2005 to 2015 where available. We chose the physician profession as a comparator for two reasons. First, to compare the growth rates to estimate the potential in alleviating shortages and expanding capacity and second, since OECD time series data on physicians are of better quality and comparability than those of the registered nursing profession.

To analyse the research objective on NPs levels of advanced practice, we performed a literature scoping review,35 focusing on a concept referred to as ‘substitution effect’, which estimates the potential of a new, extended professional role in taking up activities of an established profession.31

First phase: identification of countries and data availability—the TaskShift2Nurses Study

We identified countries with NP/APNs based on an expert survey in 39 industrialised countries (TaskShift2Nurses Study, 2015). Information on the survey itself, its sampling strategy, data collection and analysis is provided elsewhere.22 36 A total of 93 country experts participated (response rate 85.3%). The survey included questions on scope of practice and education, data availability, existence of nursing registries and mandatory versus voluntary registration policies, among others. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained at the University of Pennsylvania.

The TaskShift2Nurses Study identified 11 countries with NP/APNs: Australia, Canada, Finland, Ireland, the Netherlands, England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales, New Zealand and the USA.22 36 Definitions used were existence of NP/APNs, education at NP/APN level and advanced practice focusing on primary care, measured by seven clinical activities: authority to prescribe medications, order medical tests, decide on medical treatment, diagnose/perform advanced health assessment, referrals, responsibility for a panel of patients and first point of contact.4 The survey was integral to this study insofar, as it helped identify countries with data on NP/APN and the respective authoritative sources.

For the purpose of this study, in a subsequent step, we contacted country experts individually to obtain further information on data sources and holders. Finland and the four nations within the UK were excluded from this study, because no registry data or other national/federal or subnational data sources on NP/APNs were identified.

Second phase: country-specific secondary data collection

In a subsequent step, we retrieved secondary data on NPs for the remaining six countries from authorised sources as advised by country experts. All six countries had NP or similar roles working in advanced practice, of which the titles were regulated and registration was mandatory. The secondary data collection phase took place between August 2015 and January 2016. These sources included nursing boards or councils (Australia, Ireland and New Zealand), an institute on health information (Canada) and a nurse specialist registry (Registratiecommissie Specialismen Verpleegkunde, RSV) in the Netherlands. In the Netherlands, nurse specialists (Verpleegkundig Specialisten) are sometimes referred to as NPs in the English literature;14 however, we decided to keep the translation closest to its original title, since this title is regulated.

In the USA, several data sources were reviewed, including data from the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF),37 American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP)38 and the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.39–41 Challenges of the US data include the coexistence of multiple sources which calculate the workforce differently. The KFF provided data on professionally active NPs based on active state NP licences; however, no data on time trends were available. The AANP data cover NPs licensed to practice; however, these data are estimated and actual numbers not available to the public. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates the professionally active NP workforce, but NP-specific data are only available since 2012 and exclude self-employed NPs.39–41 To analyse the first research objective, we chose the data source based on the year of data availability (2015), the completeness of the data as to the total size of the workforce and the activity status (data covering ‘practising’ NPs, followed by professionally active and registered/licensed). For the second research objective, we prioritised on data sources with time series (ideally from 2005 to 2015 or the longest period covered).

Time series data were limited in four countries, the USA, the Netherlands, Ireland and Australia. Canada and New Zealand were the only two countries with continuous data on time series available since 2005, whereas the Netherlands had data since 2009, the year of introduction of the specialist registry, Ireland since 2010 and Australia since 2012.

Third phase: literature scoping review on the extent of advanced practice

In addition to the secondary data analysis, we conducted a comprehensive literature scoping review,35 covering MEDLINE, CINAHL, Google Scholar and grey literature, to identify studies on substitution effect/extent of advanced practice. Literature scoping reviews have evolved over the past 20 years as a method for synthesising the evidence on a specific topic or research question.35 42 Compared with systematic literature reviews, research questions in scoping reviews are broader and typically defined per PCC (Population, Concept, Context) instead of PICO (Participants, Interventions, Comparisons, Outcomes) elements,35 hence, suitable to a broader research question (see online supplementary material). Moreover, scoping reviews are designed to provide a synthesis of a wider and broader type of evidence beyond peer-reviewed journal articles, and include various, heterogeneous sources instead of focusing on the best evidence only.43 We followed the methodology by the Joanna Briggs Institute35 (see online supplementary material). Studies were included if they quantified the extent of advanced practice, also referred to as physician ‘substitution effect’. We included all evidence that measured either the percentage of typical physician-provided activities that can be performed by NPs in primary care or the percentage of all services that can be provided by NPs.31 33 Search terms included various combinations of the terms substitution, NP, primary care, among others (see online supplementary material). The search was conducted in English, plus we contacted country experts for additional grey literature.

bmjopen-2016-011901supp.pdf (508.6KB, pdf)

Data analysis

Regarding research objective 1, we calculated NP rates per 100 000 population using the population sizes provided by the OECD 2015 population statistics online database.44 To compare the density of NPs with physicians, we retrieved the physician ratios per 1000 from the OECD database, which we subsequently multiplied by 100 to obtain rates per 100 000 population.45 Data on the nursing workforce were retrieved from the same data holders from which the data on NPs were obtained, except for the Netherlands where nurse specialists are registered in a separate registry.46

As for research objective 2 on time trends, we calculated the yearly percentage change of NPs and physicians (eg, 2005–2006, 2006–2007), covering 2005–2015 or years available, to assess the relative growth of the NP profession compared with the physician profession. Percentage change is a common arithmetic method, used in many disciplines including demographics.47 It is based on the calculation of the absolute difference at two points in time and divided by the original group size, multiplied by 100. This method allows to quantify the increase or decrease over time periods irrespective of groups' differences in size. In addition to yearly percentage changes, we calculated the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) which is commonly used in comparison of time trends,48–50 since it smoothes yearly growth rates over time. In addition, we calculated the average and median percentage change across the entire time period for each country and profession covered.34

Regarding research objective 3, all studies identified from the literature scoping review were reviewed according to inclusion and exclusion criteria (see online supplementary material). Studies were included if they quantified the extent of substitution effect in primary care, provided the study was implemented in one of the six countries. We subsequently extracted the numerical results of the percentage of all services that NPs were able to provide, and information on the study design, participants, country and service delivery contexts.

Results

Total and relative size of the NP workforce

The USA showed the largest number of professionally active NPs (N=174 943) compared with the other five OECD countries, which represented 5.6% of its total active US nursing workforce in 201537 (figure 1). In the Netherlands and Canada, both the total and relative sizes were lower, the percentages were 1.5% and 1.3%, respectively, based on data on registered NPs in the Netherlands and practising NPs in Canada. In Australia, New Zealand and Ireland, the relative sizes were very small, 0.5% and less.

Figure 1.

Total number of NPs and per cent of professional nursing workforces, 2015*. Sources: Authors' calculations, based on the TaskShift2Nurses Survey 2015 and the following data sources (Dutch Nurse Specialist Registry. Unpublished data on Nurse Specialists (Verpleegkundig Specialisten), 2009 to 2015, received upon request. 2015).37 46 51–54 Notes: *2015: except for Canada, Ireland: 2014; Data on RNs include NPs. Caveats: the Netherlands (nurse specialists): an estimated 12 test accounts are in the database (0.4%) that cannot be filtered out (personal communication, with registry advisor at Verpleegkundig Specialisten Register, 29 January 2016). N, total number; NP, nurse practitioner; P, practising; PA, professionally active; R, registered/licensed to practice; RNs, registered nurses.

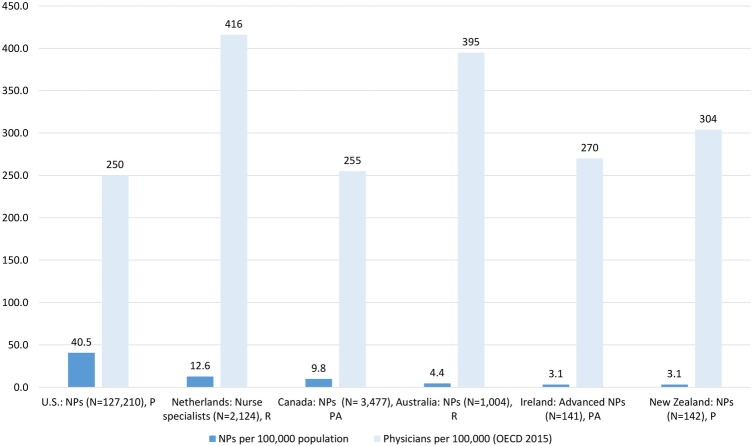

Results regarding the workforce density per population showed similar patterns across the six countries (figure 2). The rate of NPs in the USA was highest, at 40.5 practising NPs per 100 000 population44 55 based on 2012 data to allow for comparisons with physicians. NPs were less than one-fifth of the US physician workforce.44 45

Figure 2.

NP density compared with physicians per 100 000 population, 2013*. Sources: Authors' calculations, based on the following data sources (Dutch Nurse Specialist Registry. Unpublished data on Nurse Specialists (Verpleegkundig Specialisten), 2009 to 2015, received upon request. 2015).37 51–55 Data on physicians based on the OECD 2015 database,45 drawn from the following primary data sources: USA: AMA; Canada: CIHI; the Netherlands: The BIG register, Australia: AIHW, New Zealand: Medical Council Medical Register.56 57 Notes: *year 2013; except for Ireland (2014), USA (2012) depending on years covered by OECD physician data. Caveats: the Netherlands (nurse specialists): an estimated 12 test accounts are in the database that cannot be filtered out (personal communication, with registry advisor at Verpleegkundig Specialisten Register, 29 January 2016). AIHW, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; AMA, American Medical Association; CIHI, Canadian Institute for Health Information; N, total number; NPs, nurse practitioner; OECD, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development; P, practising; PA, professionally active; R, registered/licensed to practice.

In the Netherlands and Canada, the rates were considerably lower compared with the USA at 12.6 and 9.8 per 100 000 population, respectively. Compared with physicians, Australia, Ireland and New Zealand showed very low rates.

Growth of the NP workforce from 2005 to 2015

All countries showed a continuous growth of their NP workforce from 2005 to 2015 or for those years available (table 1). However, the growth rates varied considerably across countries and within countries between NPs and physicians.

Table 1.

Total number of NPs and physicians, six countries, 2005–2015 (or years available)

| USA |

Canada |

The Netherlands |

Australia |

New Zealand |

Ireland |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP | NP | MD | NP | MD | NS | MD | NP | MD | NP | MD | NP | MD | |

| Year | PA | R | R | PA | PA | R | R | R | R | R | R | PA | PA |

| 2005 | – | 106 000*† | 902 053 | 943 | 69 619 | – | 55 673 | – | 67 890 | 14 | 11 555 | – | – |

| 2006 | – | – | 921 904 | 1129 | 70 870 | – | 57 098 | – | 71 740 | 21 | 11 889 | – | 11 617 |

| 2007 | – | 120 000* | 941 304 | 1344 | 72 903 | – | 58 661 | – | 77 193 | 30 | 12 318 | – | 12 311 |

| 2008 | – | – | 954 224 | 1626 | 75 155 | – | 60 300 | – | 78 909 | 46 | 12 746 | – | 13 022 |

| 2009 | – | 130 000* | 972 376 | 1990 | 78 623 | 140 | 62 057 | – | 82 895 | 50 | 13 176 | – | 13 663 |

| 2010 | – | 140 000* | 985 375 | 2486 | 80 895 | 807 | 63 585 | – | – | 72 | 13 398 | 38 | 14 029 |

| 2011 | – | 148 000* | 1 004 635 | 2777 | 84 313 | 1272 | 65 568 | – | 87 790 | 91 | 14 021 | 97 | 14 814 |

| 2012 | 105 780‡ | 157 000* | 1 026 788 | 3157 | 87 306 | 1847 | 68 119 | 788 | 91 504 | 103 | 14 280 | 109 | 14 498 |

| 2013 | 113 370‡ | 171 000* | 1 045 910 | 3477 | 90 205 | 2124 | 69 942 | 1004 | 91 467 | 117 | 14 596 | 123 | 14 054 |

| 2014 | 122 050‡ | 192 000* | – | 3786 | – | 2480 | – | 1165 | – | 138 | 14 787 | 141 | 14 016 |

| 2015 | – | – | – | – | – | 2749 | – | 1214 | – | 157 | – | – | – |

Sources: authors' calculations, based on the following data sources (Dutch Nurse Specialist Registry. Unpublished data on Nurse Specialists (Verpleegkundig Specialisten), 2009 to 2015, received upon request. 2015),38–41 45 51–54 58–67 The OECD statistics on physicians are based on the following primary data sources: USA: AMA; Canada: CIHI; the Netherlands: The BIG register, Australia: AIHW, New Zealand: Medical Council Medical Register.56 57

Caveats: USA: ‡data on professionally active NPs do not include self-employed, hence underestimate totals,39 †year 2004 (in lieu of 2005 data availability) *data on registered NPs are estimates, exact numbers are not publicly available,38 the Netherlands: data on NS (NS, R) include ∼10 invalid cases per year used as test accounts (range 8–12) in the database that cannot be filtered out (estimated 8 cases yearly in 2009/2010/2011/2012 and 12 in 2013/2014/2015) (personal communication, with registry advisor at Verpleegkundig Specialisten Register, 29 January 2016), Canada: OECD data on MDs, based on two combined data sources, which may overstate the number of physicians, since interns and residents may be registered twice, Australia: break in OECD time series data on MDs in 2010, due to change of data holders.56 57

–, not available; AIHW, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; AMA, American Medical Association; CIHI, Canadian Institute for Health Information; MD, medical doctors/physicians; NP, nurse practitioners; NS, nurse specialists; OECD, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development; P, practising; PA, professionally active; R, registered.

In the USA, NPs licenced to practice increased from an estimated 106 000 in 2004 to 192 000 in 2014.38 The rates per 100 000 population increased from 35.87 to 60.22 NPs per 100 000 population. Data on professionally active NPs showed an increase from 105 780 to 122 050 NPs, yet were only available from 2012 to 2014.39–41

In the Netherlands, the numbers of nurse specialists registered increased rapidly, from 140 in 2009 to 2749 in 2015. The rate of nurse specialists per 100 000 population in the Netherlands showed the most rapid increase among all countries studied, more than 14-fold, from 0.85 nurse specialists in 2009 to 14.74 nurse specialists per 100 000 in 2014.

In Canada, the rate of NPs per 100 000 increased from 2.9 in 2005 to 10.7 in 2014, more than threefold. In Australia, the NP rate grew from 3.5 in 2012 to 5 per 100 000 population in 2014. Although a rapid increase took place in New Zealand from 0.3 in 2005 to 3.1 in 2014 and in Ireland from 0.8 in 2010 to 3.1 in 2014, the total numbers remained at low levels.

NP compared with physician growth rates

We present CAGRs and the median percentage changes over the 2005–2015 period to show differences in the calculation methods (table 2). In order to account for the extremely high growth rates in the first year in the Netherlands and Ireland due to the small numbers (the Netherlands 2009–2010, Ireland 2010–2011), we calculated the CAGR for the full period and the CAGR without the first year for the two countries.

Table 2.

Annual growth of the NP and physician workforces, measured by yearly percentage change, median percentage change and CAGR (%), in six countries, 2005–2015 (or years available)

| Year | USA |

Canada |

The Netherlands |

Australia |

New Zealand |

Ireland |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP | NP | MD | NP | MD | NS | MD | NP | MD | NP | MD | NP | MD | |

| PA (%)* | R† (%) | R (%) | PA (%) | PA (%) | R (%) | R (%) | R (%) | R (%) | R (%) | R (%) | PA (%) | PA (%) | |

| 2005–2006 | – | – | 2.2 | 19.7 | 1.8 | – | 2.6 | – | 5.7 | 50.0 | 2.9 | – | – |

| 2006–2007 | – | – | 2.1 | 19.0 | 2.9 | – | 2.7 | – | 7.6 | 42.9 | 3.6 | – | 6.0 |

| 2007–2008 | – | – | 1.4 | 21.0 | 3.1 | – | 2.8 | – | 2.2 | 53.3 | 3.5 | – | 5.8 |

| 2008–2009 | – | – | 1.9 | 22.4 | 4.6 | – | 2.9 | – | 5.1 | 8.7 | 3.4 | – | 4.9 |

| 2009–2010 | – | 7.7 | 1.3 | 24.9 | 2.9 | 476.4 | 2.5 | – | – | 44.0 | 1.7 | – | 2.7 |

| 2010–2011 | – | 5.7 | 2.0 | 11.7 | 4.2 | 57.6 | 3.1 | – | – | 26.4 | 4.6 | 155.3 | 5.6 |

| 2011–2012 | – | 6.1 | 2.2 | 13.7 | 3.5 | 45.2 | 3.9 | – | 4.2 | 13.2 | 1.8 | 12.4 | −2.1 |

| 2012–2013 | 7.2 | 8.9 | 1.9 | 10.1 | 3.3 | 15.0 | 2.7 | 27.4 | 0 | 13.6 | 2.2 | 12.8 | −3.1 |

| 2013–2014 | 7.7 | 12.3 | – | 8.9 | – | 16.8 | – | 16.0 | – | 17.9 | 1.3 | 14.6 | −0.3 |

| 2014–2015 | – | – | – | – | – | 10.9 | – | 4.2 | – | 13.8 | – | – | – |

| Median PC | 7.5 | 7.7 | 2 | 19.0 | 3.2 | 30.1 | 2.8 | 16.0 | 4.6 | 22.2 | 2.9 | 13.7 | 3.8 |

| CAGR | 7.4 | 6.1 (1) | 1.9 | 16.7 | 3.3 | 27.8 (2) | 2.9 | 15.5 | 3.8 | 27.3 | 2.8 | 13.3 (3) | 2.4 |

Sources: authors’ calculations, based on the following data sources (Dutch Nurse Specialist Registry. Unpublished data on Nurse Specialists (Verpleegkundig Specialisten), 2009 to 2015, received upon request. 2015).38–41 45 51–54 58–67 The OECD statistics on physicians are based on the following primary data sources: USA: AMA; Canada: CIHI; the Netherlands: The BIG register, Australia: AIHW, New Zealand: Medical Council Medical Register.56 57

Caveats: USA: *data on professionally active NPs do not include self-employed.39 †Data on registered NPs are estimates, exact numbers are not publicly available,38 the Netherlands: data on NS (NS, R) include ∼10 invalid cases per year used as test accounts (range 8–12) in the database that cannot be filtered out (estimated 8 cases yearly in 2009/2010/2011/2012 and 12 in 2013/2014/2015) (personal communication, with registry advisor at Verpleegkundig Specialisten Register, 29 January 2016), Canada: OECD data on MDs, based on two combined data sources, which may overstate the number of physicians, since interns and residents may be registered twice, Australia: break in OECD time series data on MDs in 2010, due to change of data holders.56 57

–, not available; AIHW, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; AMA, American Medical Association; CAGR, compound annual growth rate, (1)=CAGR (2004/2014) calculated based on 2004–2014 data (2004 data used in lieu of missing 2005 data) (2)=CAGR (2010–2015), 2009–2010 was excluded due to excessive growth rate caused by small numbers (CAGR 2009–2015: 64.3%, not shown), (3)=CAGR (2011–2014), 2010–2011 data excluded (CAGR 2010–2014: 38.8%, not shown); CIHI, Canadian Institute for Health Information; MD, medical doctors/physicians; NP, nurse practitioners; NS, nurse specialists; OECD, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development; P, practising; PA, professionally active; PC, percentage change; R, registered.

Growth among NPs was high in all countries, and consistently and considerably higher than among physicians. The compound growth rate among nurse specialists in the Netherlands was 27.8% (CAGR 2010–2015), the highest among all six countries. The yearly growth was higher than that of its medical workforce at 2.9%, the overall yearly growth was more than nine times higher. In New Zealand and Canada, the compound annual growth of NPs was 27.3% and 16.7%, respectively, approximately nine and five times higher than that of their medical workforces (2.8% and 3.3%). Ireland showed a comparatively lower yearly increase of its NP workforce, yet, still it was more than five times growth compared with its physician workforce. Of the six countries, the USA had the lowest annual compound growth of 6.1% or 7.4% annually depending on the data sources, yet, was still more than three times higher than that of physicians.38–41 44 45

Extent of advanced clinical practice

The scoping review yielded a total of 1022 results. After removal of 31 duplicates, the titles of 991 records were screened and the full text of 46 studies analysed according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria (see online supplementary material for additional information). The review resulted in five papers, together reporting the findings from three empirical studies, quantifying the extent of clinical practice of NPs compared with physicians in primary care. These were conducted in the USA, Canada and the Netherlands (table 3). No studies conducted in the three other countries were identified. The studies found that NPs were able to provide between 67% and 93% of primary care services, emanating from one randomised controlled trial (RCT) conducted in Canada,68 one quasi-experimental study in the Netherlands,69–71 and one survey of physicians and NPs in the USA28 (see online supplementary material). The findings were based on small sample sizes, did not differentiate between specialty areas of NPs and covered different practice areas within primary care, such as rural areas in the USA28 or out-of-hours services in the Netherlands. Moreover, the RCT in Canada was conducted more than 40 years ago.68

Table 3.

Level of advanced clinical practice, measured by physician ‘substitution effect’ of NPs

| Country | Study design (years) | Setting | Participants | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | RCT to assess the effects of substituting NPs for physicians in primary care (1971–1972) | 2 suburban Ontario family practices | Total patient N=1598 families (4325 individuals) of which 529 families (1398 individuals) were randomised to each physician; 270 families (765 individuals) were randomised to each NP | 67% of all primary care patient visits can be provided by NPs. Care delivery was similar between physicians and NPs. There were no statistically significant differences between patients seen by NPs compared with patients seen by physicians in patient functional capacity, indexes of social and emotional function, mortality or satisfaction with care. |

68 |

| The Netherlands | Quasi-experimental study to compare the number of patients and caseloads between nurse specialists and GPs in out-of-hours services (2011–2012) | Out-of-hours primary care | Intervention: 1 NP and 4 GPs, control: 5 GPs working in out-of-hours services. Total patient N=12 092 from 1 GP cooperative extracted from medical records | More than 77% of patients fit the scope of practice of (Verpleegkundig Specialist) in out-of-hours care. On average 16.3% of all patients were treated by nurse specialists, whereas 20.9% of patients were treated by GPs. 75–83% of clinical activities in out-of-hours primary care settings (weekend shifts in GP practices) could be taken over by nurse specialists. |

69–71 |

| USA | Self-report, mailed survey to a random sample of 4000 physicians and 3000 NPs with rural addresses (all specialties) | Rural primary care in 13 states with at least 2 from each US Census Region (4 regions) | Final sample included 788 primary care physicians (response rate: 25%); and 918 primary care NPs (40%) | 75–93% of weekly primary care outpatient visits can be provided by NPs.* In the outpatient setting, primary care clinical activities† were comparable between physicians and NPs in the outpatient setting. |

28 |

Source: See directly in the table, see online supplementary material for more details.

*In an unadjusted regression model, NP average weekly number of outpatient visits was 75% of physician volume. In an adjusted model (age, sex, geographic location, and practice setting), NP average weekly number of outpatient visits was 93% of physician volume.

†On average, physicians conducted more well-child visits than NPs (12.6 vs 7.4, p<0.001). Differences for prenatal visits and minor procedures were non-significant.

GP, general practitioner; NP, nurse practitioners; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Discussion

The size of the NP workforce in the six countries studied is variable, but growing rapidly. The workforce shows high levels of practice in primary care, yet based on limited evidence. The USA is the only country where the NP workforce has reached a considerable density of ∼40.5 practising NPs per 100 000 population, in other countries the workforce is smaller, ranging from 12.6 per 100 000 population in the Netherlands to low levels in New Zealand and Ireland. Yet, the NP workforce has rapidly and consistently grown since 2005 in all countries, at much higher rates than the physician workforce. Moreover, the few existing empirical studies show the potentially large and wide range of advanced clinical activities that NPs can provide. The studies suggest that between 67% and 93% of primary care visits and services can be safely provided by NPs. Taken together, the findings indicate that the NP workforce holds future promise in filling unmet care needs in primary care.

The study faces several limitations. First, data sources varied in the activity levels covered, for example, practising, professionally active or registered NPs and physicians across countries. This limitation is faced by all international data on health workforces, including the OECD and WHO, since countries use different registration policies and data collection methodologies. However, for within-country comparisons, we consistently compared the same activity levels of NPs and physicians. Second, we took the OECD data on physicians at face value; however, among the underlying primary data sources, differences may exist in terms of accuracy and validity. Future research could compare the accuracy of the OECD data with individual national/subnational primary data sources. Third, due to the US decentralised approach of licensing NPs, several different data sources and holders were identified. Large differences exist across data sources in terms of size, and activity levels, limiting the overall quality of data. Additionally, state-level authority over NP licensing may lead to double counting of NPs who hold licences in multiple states. Moreover, data on time trends of 10 years were based on estimates and covered the licensed workforce. Hence, the US data can at best be approximations of the actual number of practising NPs over the 10-year period and therefore need to be interpreted in light of the limitations.

Our results are largely in line with previous international research showing the relatively small scale of the NP workforce.20 24 Reasons for the differences between the scale of the NP workforce in the USA and other countries have not been empirically analysed. It is assumed they may be multifactorial. The years of existence may play a role, as the USA was the first country to implement NPs in 1965 (in the earliest adopting state); other factors may also influence their size and growth. Canada (Nova Scotia) introduced the first NPs only 2 years later, but relies on a much lower total number and density of NPs than the USA. Reasons for a small NP base in Canada have been discussed, and include limited role clarity, differences across provinces and territories in education and uptake, and challenges in creating positions for NPs.12 29 72 Moreover, large variations in the NP density exist across provinces and territories, rural versus urban areas and by employer, suggesting a more granular analysis of potentially influencing policies and other factors may be needed.51 The low numbers in the Netherlands, Australia, and particularly in New Zealand and Ireland are at least partly influenced by the fact that NPs were introduced much later in these countries (1990s and 2000s) than in the USA and Canada.13 24 60 73–75

Time series data showed a considerable increase of NPs in all countries studied, much higher yearly growth than found in the medical workforces. This trend may partially but not entirely be related to the fact that increases in very small numbers result in large growth rates. We took account of this by excluding extreme values from the CAGR calculations for Ireland and the Netherlands, and calculated median percentage changes which were comparable to CAGR.

The continuous and higher growth rates point to an emerging NP workforce that may not have reached its full numerical potential, as compared with professions with a longer tradition, such as the physician workforce. Many countries in our study have removed or eased regulatory barriers to expanded NP scope of practice, such as Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the Netherlands and the USA.76–80 Canada and New Zealand expanded prescriptive authority for NPs in 2012 and 2014, respectively.77 81 In Australia, NPs got access to the Medical and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme in 2010, easing their practice, the Netherlands has regulated the nurse specialist profession in 2009 and expanded scope of practice in 2011, entering into effect in 2012.78 82 In the USA, an increasing number of states have removed regulatory barriers by revising scope of practice laws over the last decade.79 83 Future research is warranted to identify systemic facilitators and barriers that may cause variations in the implementation of NP roles in different country contexts.

Moreover, medical student intake or residency places are restricted by some sort of quota system or numerus clausus in all countries, to avoid an excessive medical workforce and at the same time, physician shortages.84 These regulatory measures may explain the moderate annual increase among the medical workforce. To which extent countries' workforce planning take account of NPs or other APNs to project student intake, has received little attention in research and practice. Future research on workforce planning should include NPs in relation to physician growth and the potential for substitution, such as estimating the number of ‘physician-equivalent NPs’ as a strategy to ease future projected workforce shortages. In the Netherlands, for instance, nurse specialists have been added to its physician workforce projection as one scenario to account for substitution.33 Yet, reasons for cross-country variations in health workforce supply, skill-mix changes across high-income countries and access to care is one area of research that warrant further high-quality evaluations.

The findings from our literature scoping review show that NPs could cover a range of ∼67–93% of all primary care services. Findings are largely in line with a report by the American College of Physicians, suggesting that 60–90% of primary care can be provided by NPs.85 A previous review showed a lower range of 30–70% of physician-provided activities that could be taken over by NPs, yet comparability is limited, since the review covered NPs and other non-physician providers.31 Yet, the number of empirical studies we identified is small, does not take into account variations in specialty areas, is based on small sample sizes and was conducted in different provider contexts. Hence, the findings require cautious interpretation of the data and call for more research in the field.

This study shows a rapid yearly increase of the NP workforce, which suggests that more attention should be paid to the monitoring of this workforce in the future to expand capacity and access to healthcare services. To date, data on the NP workforce are not covered in international health workforce databases, such as the WHO, OECD or international nursing bodies and associations. Most data are publicly available or available on request from the respective nursing regulatory bodies' websites or other data holders. In the USA with the numerically largest workforce, data availability is limited, a barrier for the monitoring of the workforce. Integrating NPs in health workforce data and intelligence systems at national and international level is therefore critical for their development, education and monitoring.

Conclusions

NPs are a rapidly growing workforce internationally, growing faster than the medical profession in the six countries studied. Data on the size and growth of NPs are available in all six countries, however, with variations in quality and completeness, particularly on time trends. Information on the extent of potential physician substitution effect is limited, yet, relevant for workforce planning. As this workforce grows, improving data availability and monitoring as part of the overall health workforce is critical to inform educational capacity, uptake in practice and workforce planning.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Dutch Registration Commission for Nurse Specialists in the Netherlands (Registratiecommissie Specialismen Verpleegkunde, RSV) for their support in providing time series data and important additional contextual information. Moreover, the authors also thank the 93 country experts who participated in the survey. In particular, they thank the following country experts for providing additional information on data sources: Julianne Bryce, Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation; Miranda Laurant, HAN University of Applied Sciences, Faculty of Health and Social Studies, the Netherlands; Marieke Kroezen, Catholic University Leuven, Belgium; Jenny Carryer, Massey University and College of Nurses, New Zealand; Anne-Marie Brady, Trinity College Dublin, Republic of Ireland; Barbara Todd, Hospital University of Pennsylvania; Kenneth Miller, American Association of Nurse Practitioners.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Claudia Maier at @clamaier and Hilary Barnes at @HbarnesPhD

Contributors: CBM had the main role in the study design, data collection and analysis, and wrote the manuscript. HB contributed to the identification of US data and the literature review, and was involved in the revisions of the manuscript. LHA and RB gave overall guidance on the study, the methodology and reviewed the paper. All authors read, commented on and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by The Commonwealth Fund and the B. Braun Foundation, through the Harkness Fellowship (Maier), and the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research (grant number T32NR007104, LHA, principal investigator).

Disclaimer: The views presented here are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the funders who had no role in the study.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: CBM had financial support for the TaskShift2Nurses Study from the Commonwealth Fund and B. Braun Foundation, through the Harkness Fellowship, LHA received funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Institute of Nursing Research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data on the total number of nurse practitioners are available in the manuscript. All other data (eg, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) data) are publicly available.

References

- 1.Cometto G, Boerma T, Campbell J et al. The Third Global Forum: framing the health workforce agenda for universal health coverage. Lancet Glob Health 2013;1:e324–5. 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70082-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. A universal truth: no health without a workforce. Third Global Forum on Human Resources for Health Report. Report No.: Forum Report, Third Global Forum on Human Resources for Health Global Health Workforce Alliance and World Health Organization, November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.OECD. Health workforce policies in OECD countries: right jobs, right skills, right places. Paris, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Council of Nurses. International Council of Nurses: definition and characteristics for nurse practitioner/advanced practice nursing roles. Geneva, 2002. (updated October 2014; cited April 2016). https://acnp.org.au/sites/default/files/33/definition_of_apn-np.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Task shifting to tackle health worker shortages. WHO/HSS/200703, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Task shifting: rational redistribution of tasks among health workforce teams: global recommendations and guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stanik-Hutt J, Newhouse RP, White KM et al. The quality and effectiveness of care provided by nurse practitioners. J Nurse Pract 2013;9:492–500.e13. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinez-Gonzalez NA, Tandjung R, Djalali S et al. Effects of physician-nurse substitution on clinical parameters: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e89181 10.1371/journal.pone.0089181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez-Gonzalez NA, Djalali S, Tandjung R et al. Substitution of physicians by nurses in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:214 10.1186/1472-6963-14-214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinez-Gonzalez NA, Rosemann T, Tandjung R et al. The effect of physician-nurse substitution in primary care in chronic diseases: a systematic review. Swiss Med Wkly 2015;145:w14031 10.4414/smw.2015.14031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mundinger MO. Advanced-practice nursing—good medicine for physicians? N Engl J Med 1994;330:211–14. 10.1056/NEJM199401203300314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin-Misener R, Bryant-Lukosius D, Harbman P et al. Education of advanced practice nurses in Canada. Nurs Leadersh (Tor Ont) 2010;23 Spec No:61–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gagan MJ, Boyd M, Wysocki K et al. The first decade of nurse practitioners in New Zealand: a survey of an evolving practice. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2014;26:612–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ter Maten-Speksnijder A, Grypdonck M, Pool A et al. A literature review of the Dutch debate on the nurse practitioner role: efficiency vs. professional development. Int Nurs Rev 2014;61:44–54. 10.1111/inr.12071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacLellan L, Higgins I, Levett-Jones T. Medical acceptance of the nurse practitioner role in Australia: a decade on. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2015;27:152–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Begley C, Elliott N, Lalor J et al. Differences between clinical specialist and advanced practitioner clinical practice, leadership, and research roles, responsibilities, and perceived outcomes (the SCAPE study). J Adv Nurs 2013;69:1323–37. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06124.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.NHS Education for Scotland. Advanced Nursing Practice Toolkit. Current issues in regulation 2012. September 2015. http://www.advancedpractice.scot.nhs.uk/regulatory-guidance/current-issues-in-regulation.aspx

- 18.Chamberlain P, Brown CH, Saldana L. Observational measure of implementation progress in community based settings: the Stages of Implementation Completion (SIC). Implement Sci 2011;6:116 10.1186/1748-5908-6-116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pulcini J, Jelic M, Gul R et al. An international survey on advanced practice nursing education, practice, and regulation. J Nurs Scholarsh 2010;42:31–9. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01322.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delamaire ML, Lafortune G. Nurses in advanced roles: A description and evaluation of experiences in 12 developed countries. OECD Health Working Paper 2010;54 (DELSA/HEA/WD/HWP (2010)5). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heale R, Rieck Buckley C. An international perspective of advanced practice nursing regulation. Int Nurs Rev 2015;62:421–9. 10.1111/inr.12193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maier CB. The role of governance in implementing task-shifting from physicians to nurses in advanced roles in Europe, U.S., Canada, New Zealand and Australia. Health Policy 2015;119:1627–35. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carney M. Regulation of advanced nurse practice: its existence and regulatory dimensions from an international perspective. J Nurs Manag 2016;24:105–14. 10.1111/jonm.12278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freund T, Everett C, Griffiths P et al. Skill mix, roles and remuneration in the primary care workforce: who are the healthcare professionals in the primary care teams across the world? Int J Nurs Stud 2015;52:727–43. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spetz J, Fraher E, Li Y et al. How many nurse practitioners provide primary care? It depends on how you count them. Med Care Res Rev 2015;72:359–75. 10.1177/1077558715579868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hooker RS, Brock DM, Cook ML. Characteristics of nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the United States. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2016;28:39–46. 10.1002/2327-6924.12293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kleinpell R, Goolsby MJ. American Academy of Nurse Practitioners National Nurse Practitioner Sample Survey: focus on acute care. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2012;24:690–4. 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2012.00777.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doescher MP, Andrilla CHA, Skillman SM et al. The contribution of physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners toward rural primary care findings from a 13-state survey. Med Care 2014;52:549–56. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sangster-Gormley E, Martin-Misener R, Downe-Wamboldt B et al. Factors affecting nurse practitioner role implementation in Canadian practice settings: an integrative review. J Adv Nurs 2011;67:1178–90. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05571.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lowe G, Plummer V, Boyd L. Nurse practitioner roles in Australian healthcare settings. Nurs Manag (Harrow) 2013;20: 28–35. 10.7748/nm2013.05.20.2.28.e1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richardson G, Maynard A. Fewer doctors? More nurses? A review of the knowledge base of doctor-nurse substitution. York: Centre for Health Economics, York Health Economics Consortium, University of York, 1995. Contract No.: 135. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laurant M, Reeves D, Hermens R et al. Substitution of doctors by nurses in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(2):CD001271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Advisory Committee on Medical Manpower Planning (Capaciteitsorgaan). The 2013 Recommendations for Medical Specialist Training. In the medical, dental, clinical, technological and mental health areas of training. Utrecht, 2013. (cited September 2015). http://www.capaciteitsorgaan.nl/Portals/0/capaciteitsorgaan/publicaties/Capaciteitsplan%202013/DEFINITIEF%20hoofdrapport%20engels%20compl.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 34.OECD Health Statistics. OECD Health Statistics 2015. Definitions, sources and methods. Metadata. OECD, November 2015. Report No. [Google Scholar]

- 35.The Joanna Briggs Institute. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2015. Methodology for JBI scoping reviews. The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI), 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maier CB, Aiken LH. Task-shifting from physicians to nurses in primary care in 39 countries: a cross-country comparative study. Eur J Public Health 2016. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaiser Family Foundation. Total number of nurse practitioners, by gender. State Health Facts: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2015. (cited August 2015). http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-number-of-nurse-practitioners-by-gender/ [Google Scholar]

- 38.American Association of Nurse Practitioners. AANP—about us—historical timeline. American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP), 2015. (cited December 2015). https://www.aanp.org/about-aanp/historical-timeline [Google Scholar]

- 39.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Employment and Wages, May 2014. 29-1171 Nurse Practitioners. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), 2014. (cited December 2015). http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291171.htm.

- 40.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Employment and Wages, May 2012. 29-1171 Nurse Practitioners. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), 2012. (cited December 2015). http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291171.htm.

- 41.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Employment and Wages, May 2013. 29-1171 Nurse Practitioners. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), 2013. (cited December 2015). http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291171.htm.

- 42.Armstrong R, Hall BJ, Doyle J et al. Cochrane update. ‘Scoping the scope’ of a Cochrane review. J Public Health (Oxf) 2011;33:147–50. 10.1093/pubmed/fdr015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cacchione PZ. The evolving methodology of scoping reviews. Clin Nurs Res 2016;25:115–19. 10.1177/1054773816637493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.OECD. Population Statistics. OECD.Stat 2015. (cited December 2015). http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DatasetCode=POP_FIVE_HIST

- 45.OECD. Healthcare Resources: Physicians. OECD.Stat 2015. (cited December 2015). http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?DataSetCode=HEALTH_STAT

- 46.Dutch health professional register (BIG register). Numbers [Cijfers] of health professionals. Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports, 2015. (cited December 2015). https://www.bigregister.nl/overbigregister/cijfers/ [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rowland D. Demographic methods and concepts. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reinhardt UE, Hussey PS, Anderson GF. Cross-national comparisons of health systems using OECD data, 1999. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:169–81. 10.1377/hlthaff.21.3.169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brownson RC, Boehmer TK, Luke DA. Declining rates of physical activity in the United States: what are the contributors? Annu Rev Public Health 2005;26:421–43. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anderson GF, Reinhardt UE, Hussey PS et al. It's the prices, stupid: why the United States is so different from other countries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2003;22:89–105. 10.1377/hlthaff.22.3.89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Regulated Nurses, 2014. Health workforce database. Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2015. (cited November 2015). https://secure.cihi.ca/estore/productFamily.htm?locale=en&pf=PFC2898&lang=en [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nursing and Midwifery Board of Ireland. Statistics. Register statistics 2014 2015. (cited November 2015). http://www.nursingboard.ie/en/statistics.aspx

- 53.Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia. Statistics. 2015 June 2015. Report No (cited December 2015). http://www.nursingmidwiferyboard.gov.au/About/Statistics.aspx.

- 54.Nursing Council of New Zealand. Annual report 2015. Wellington, New Zealand: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 55.U.S. HRSA National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. Highlights from the 2012 National Sample Survey of Nurse Practitioners. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 56.OECD. OECD Health Statistics 2015. Definitions, sources and methods. Physicians licensed to practice OECD. OECD Health Statistics, July 2015 (cited November 2015). http://www.oecd.org/health/health-data.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 57.OECD. OECD Health Statistics 2015. Definitions, sources and methods. Professionally active physicians. OECD, OECD Health Statistics, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nursing Council of New Zealand. Report of the Nursing Council of New Zealand for the year ended 31 March 2005. Presented to the Minister of Health pursuant to Section 134 of the Health Practitioners Competence Assurance Act 2003 Wellington, New Zealand, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nursing Council of New Zealand. Report of the Nursing Council of New Zealand for the year ended 31 March 2006. Presented to the Minister of Health pursuant to Section 134 of the Health Practitioners Competence Assurance Act 2003 Wellington, New Zealand, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nursing Council of New Zealand. Report of the Nursing Council of New Zealand for the year ended 31 March 2007. Presented to the Minister of Health pursuant to Section 134 of the Health Practitioners Competence Assurance Act 2003 Wellington, New Zealand, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nursing Council of New Zealand. Annual report 2009. Wellington, New Zealand, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nursing Council of New Zealand. Annual report 2010. Wellington, New Zealand, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nursing Council of New Zealand. Annual report 2011. Wellington, New Zealand, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nursing Council of New Zealand. Annual report 2012. Wellington, New Zealand, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nursing Council of New Zealand. Annual report 2013. Wellington, New Zealand, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nursing Council of New Zealand. Annual report 2014. Wellington, New Zealand, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nursing Council of New Zealand. Report of the Nursing Council of New Zealand for the year ended 31 March 2008. Presented to the Minister of Health pursuant to Section 134 of the Health Practitioners Competence Assurance Act 2003 Wellington, New Zealand, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Spitzer WO, Sackett DL, Sibley JC et al. The Burlington randomized trial of the nurse practitioner. N Engl J Med 1974;290:251–6. 10.1056/NEJM197401312900506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van der Biezen M, Schoonhoven L, Wijers N et al. Substitution of general practitioners by nurse practitioners in out-of-hours primary care: a quasi-experimental study. J Adv Nurs 2016;72:1813–24. 10.1111/jan.12954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wijers N, van der Burgt R, Laurant M. Verpleegkundig Specialist biedt kansen. Onderzoeksrapport naar de inzet van de verpleegkundig specialist op de spoedpost in Eindhoven. [Specialist Nursing offers opportunities. Research report into the use of the specialist nurse at the emergency station in Eindhoven]. Nijmegen: IQ healthcare, UMC St Radboud; Eindhoven: KOH Foundation, 2013. https://www.stichtingkoh.nl/cms_file.php?fromDB=834&forceDownload. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Laurant M. Out of hours primary care. International Innovation, 2013. (cited December 2015). http://rcpsc.medical.org/publicpolicy/imwc/out_of_hours_primary_care_interview_miranda_laurant.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 72.DiCenso A, Bryant-Lukosius D, Martin-Misener R et al. Factors enabling advanced practice nursing role integration in Canada. Nurs Leadersh (Tor Ont) 2010;23 Spec No:211–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Minto R. Barriers on nurse practitioner journey. Nurs N Z 2008;14:4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Begley C, Murphy K, Higgins A et al. Policy-makers’ views on impact of specialist and advanced practitioner roles in Ireland: the SCAPE study. J Nurs Manag 2014;22:410–22. 10.1111/jonm.12018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Scanlon A, Cashin A, Bryce J et al. The complexities of defining nurse practitioner scope of practice in the Australian context. Collegian 2016;23:129–42. 10.1016/j.colegn.2014.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cashin A. Collaborative arrangements for Australian nurse practitioners: a policy analysis. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2014;26:550–4. 10.1002/2327-6924.12164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Parliament of New Zealand. Misuse of Drugs Amendment Regulations 2014. 2014/199 2014. (cited December 2015). http://www.legislation.govt.nz/regulation/public/2014/0199/latest/DLM6156029.html?search=qs_regulation%40deemedreg_Misuse+of+drugs+act_resel_25_h&p=1.

- 78.van Meersbergen D. Task-shifting in the Netherlands. World Med J 2011;57:126–30. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Phillips SJ. 28th annual APRN legislative update: advancements continue for APRN practice. Nurse Pract 2016;41:21–48. 10.1097/01.NPR.0000475369.78429.54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kroezen M, van Dijk L, Groenewegen PP et al. Nurse prescribing of medicines in Western European and Anglo-Saxon countries: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Government of Canada. Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. New Classes of Practitioners Regulations. Canada Gazette 2012;146 (cited December 2015). http://www.gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p1/2012/2012-05-05/html/reg1-eng.html. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Australian Government. Health Legislation Amendment (Midwives and Nurse Practitioners) Act 2010. No. 29, 2010. C2010A00029 2010. (cited December 2015). https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2010A00029.

- 83.Phillips SJ. 27th Annual APRN legislative update: advancements continue for APRN practice. Nurse Pract 2015;40:16–42. 10.1097/01.NPR.0000457433.04789.ec [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ono T, Lafortune G, Schoenstein M. Health workforce planning in OECD countries: a review of 26 projection models from 18 countries. OECD Health Working Papers. 2013 October 2015 (cited October 2015); No. 62 10.1787/5k44t787zcwb-en [DOI]

- 85.American College of Physicians. Nurse practitioners in primary care. Philadelphia: American College of Physicians, 2009. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-011901supp.pdf (508.6KB, pdf)