Abstract

Objective

To determine whether preoperative psychological depression and/or serotonin transporter gene polymorphism are associated with poor outcomes after the common procedure of laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Design

Patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy were genotyped for the serotonin transporter gene 5-HTTLPR polymorphism and assessed for psychological morbidity before and 6 weeks after surgery. The main outcome was postoperative depression; secondary outcomes included fatigue, perceived pain, quality of life and subjective perception about return to usual.

Results

Full genetic and psychological data were obtained from 273 out of 330 patients consented to the study (82% female). Significantly fewer people with preoperative depression (Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score >5) had returned to employment (57% vs 86%, p<0.001) or made a full recovery (11% vs 44%, p<0.001) 6 weeks after surgery. Independent predictors for subjective return to usual after surgery included preoperative depression, body mass index and postoperative pain scores. Independent predictors of postoperative depression included preoperative antidepressant use and preoperative depression. SS genotype was associated with use of antidepressants preoperatively and higher anxiety levels after surgery. However, it was not associated with other salient postoperative psychosocial outcomes.

Conclusions

Depressive psychological morbidity preoperatively, pain and body mass index appear to be important factors in predicting recovery after this common surgical procedure. There may be a place to include preoperative brief psychological screening to enable targeted support. Our results suggest that the serotonin transporter gene is unlikely to be a useful clinical predictor of outcome in this group.

Trial registration number

ISRCTN40219584.

Keywords: MENTAL HEALTH, GENETICS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

First to explore depression status and serotonin transporter gene polymorphism status together in a population of patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Prospective study.

Reinforces research from other surgical samples suggesting that preoperative psychological morbidity influences postoperative outcomes.

Relatively small sample size (330).

Introduction

Predictors of psychosocial outcome after major surgery include patients' psychological morbidity, past adaptation to stressors, history of compliance with treatment, substance abuse, obesity, level of social support and pain control.1–3 Biological markers have been investigated in relation to some outcomes after major surgery4 but not, to date, for good or poor psychological recovery. One candidate potentially worthy of further research is the serotonin transporter gene. This has been reported to be associated with psychological outcomes after significant life events.5–7 The promoter region contains the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism, which exists as long (L) and short (S) alleles. The S allele has been reported to be associated with reduced serotonin transporter expression,8 and has been suggested to represent a risk allele for anxiety9 and depression,10 particularly in the presence of stressful life events.5 The strength of these claims is under debate11 and as yet unresolved.12 13

Early work suggested that 5-HTTLPR genotype is associated with some clinical outcomes such as survival after major colorectal surgery.14 However, outcomes after less morbid operations, such as laparoscopic cholecystectomy, have not been studied in this context. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is of particular interest as it is a common procedure from which patients' propensity to fully recover varies substantially between individuals, even with uncomplicated surgery. Moreover, this procedure does not carry the psychological overlay of cancer or chronic disease which could potentially confound. Consequently, this study seeks to determine whether this biological marker is associated with poorer mood, as well as other important psychosocial outcomes (postoperative fatigue, quality of life and pain perception) after this surgical procedure.

In this study, we investigated the association between 5-HTTLPR genotype and recovery from laparoscopic cholecystectomy. An association with psychological outcome might lead to further studies of prophylactic prevention of depression in those at high risk, therefore potentially improving postoperative outcomes and costs in a proportion of patients (around 20% of people with European ancestry are homozygous for the S allele).15 This study therefore sought to establish whether there is sufficient evidence to justify a clinical trial.

Methods

Full ethics committee and governance approval was obtained. We followed the STROBE recommendations for observational studies. We recruited participants by obtaining fully informed consent from consecutive patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy at a District Teaching Hospital. Patients under 18 or over 65 years of age were excluded as studies show that the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism is less likely to have an impact in these age ranges.7 Patients were also excluded if they had significant cognitive or psychological impairment, or were unable to read or understand written English. Participation in the study was discontinued if patients underwent conversion to an open operation. Demographic and salient medical information was systematically and prospectively collected.

To assess the ‘participants’ 5-HTTLPR genotype, a sample of the participants DNA (genetic material) was collected using buccal swab (with four replicates). Samples were refrigerated and analysed at the Biology Department of the University of York. Two of the four buccal mucosal swab replicates were processed for PCR analysis using well-established procedures for this material. Oligonucleotide primers designed to specifically prime PCR amplification for the region of the serotonin transporter gene promoter, which includes the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism,5 was synthesised and tested for unique amplification of the correct human sequences by determination of the correct size PCR product and by DNA sequencing. Control samples from non-study individuals were characterised for the polymorphism and used as standards for the analysis of the polymorphism in the experimental group. Analysis of the polymorphism in the PCR products was conducted using a multichannel DNA sequencing machine, which automatically recorded the sizes of the DNA onto a computer for transfer into the database of the experimental group. High-level quality assurance procedures ensured correct matching of DNA results with the individuals in the database. Where the two replicates did not yield any result or were indeterminate, the further two replicates were analysed.

Psychosocial assessments were made at preoperative assessment and during clinic attendance 6 weeks after surgery using the following instruments.

The primary outcome was the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) short form16 routinely used in research. This is a well-established measure of depression. A score above 5 on the BDI was used as this is the established cut-off point indicating mild depression.

Validated secondary outcomes included:

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) Scale,17 a scale used to monitor depression and anxiety levels in general hospital patients that is routinely used in clinical practice. A cut-off of 8–10 indicates borderline and 11–21 abnormal anxiety or depression.

The Chalder Fatigue Scale18 is an ordinal dimensional scale to measure fatigue severity. A score of 4 or above suggesting significant fatigue levels

The 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36)19 is a commonly used generic profile instrument to measure health-related quality of life, which produces eight different subscales including pain and fatigue.

The Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ-R) short form (neuroticism subscale),15 20 a well-validated personality scale.

Unvalidated secondary outcomes included:

A visual analogue scale (0–100) to assess pain, which was given at day 1 and 6 weeks postsurgery.

A questionnaire to assess common postoperative milestones (eg, time to driving and time to work) was given at 6 weeks. This also asked patients to rate their return to usual health on a 0–100% scale.

Statistical methods

Power calculations suggested that 240 patients were needed, given a distribution of the LL allele in a ratio of 3:7 (43%),5 to detect an effect size of d=0.5 on the BDI using linear transformed scales, with 80% power and type I error of 1% (corrected for assessment of multiple scores). We approached 330 patients for entry into the study to allow for those declining to consent and for subsequent attrition.

Descriptive analysis for each genotype was mean (SD) for continuous data, n (%) for categorical data and median (IQR) for ordinal data. Analysis of variance was used to compare genotype for continuous variables, χ2 for categorical variables and Kruskall-Wallis for visual analogue or ordinal data. Logistic regression was used to compare BDI and Chalder fatigue scores between genotype postoperatively, adjusting for preoperative scores, and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to compare SF-36, Pain and EPQ between genotype postoperatively, adjusting for preoperative scores of other variables. Linear regression analysis was used to explore variables associated with patients self-rating (0–100) of their return to usual at 6 weeks postsurgery, and logistic regression for return to work.

All analyses were undertaken on SPSS (V.20). A p value of <0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance. No adjustments were made for multiple testing in line with recommendations by Perneger (1998),21 who stated that simply describing what tests of significance have been performed, and why, is generally the best way of dealing with multiple comparisons.

Results

Preoperative status

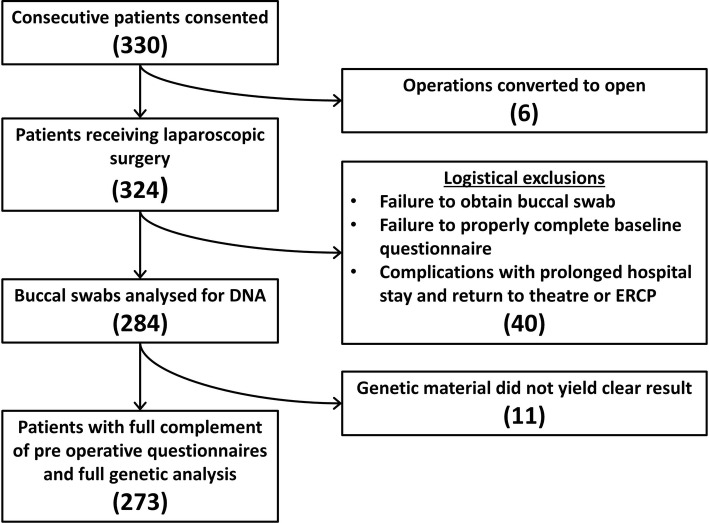

Three hundred and thirty preoperative patients were consented to take part in the study. Ultimately, 46 patients were excluded because of conversion to open surgery, prolonged hospital stay for complications, failure to obtain a buccal swab or failure to complete the baseline questionnaire. A further 11 were also excluded due to an unresolved genotype, either because no material could be detected on the swab or because technical resolution of genotype was not possible, with requests for further swabs being unsuccessful. The postoperative BDI was properly completed by 227 patients (83%; figure 1 summarises these data).

Figure 1.

Flow of patients through the study. ERCP, Endoscopic retrograde Cholangio pancreatography.

Six of the 330 patients required conversion to open cholecystectomy (1.8%) and delayed discharge occurred in 5 (1.5%). Subsequent readmission was necessary in 16 (4.9%), of whom 11 had abnormal liver function tests associated with pain. Three of these patients had a common bile duct stone removed. One further patient required laparotomy for biliary peritonitis due to a leak from the cystic duct. There were no bile duct injuries.

Descriptive summary by genotype

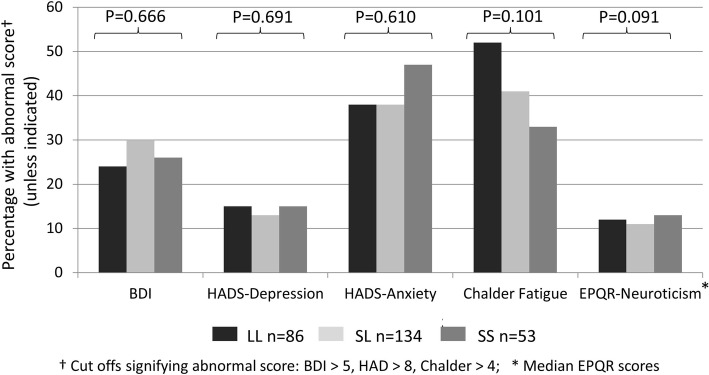

Of the 275 patients, 86 (31%) were homozygous for the L allele (LL), 53 (19%) for the S allele (SS) and 136 (50%) were heterozygous (SL). There was no evidence of differences between 5-HTTLPR genotypes with respect to gender (p=0.522), age (P=0.490), body mass index (BMI; p=0.498), previous operations (p=0.608), number of previous significant life events (p=0.172), employment status (0.344) or socioeconomic status (SES; p=0.141). However, significantly more patients with the SS genotype had a history of antidepressant use (47%) compared with the LL (24%) or the SL (28%) genotypes (p=0.032). This was nearly twice as many for SS compared with LL. None of the preoperative patient-reported outcome measures was associated with 5-HTTLPR genotype (figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Percentage of preoperative abnormal questionnaire scores by serotonin transporter gene polymorphism. BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; EPQ-R, Eysenck Personality Questionnaire; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Figure 3.

Preoperative SF-36 subscale scores by serotonin transporter gene polymorphism. SF-36, 36-item Short Form Health Survey.

Postoperative outcome measures

Primary outcome: BDI

Using the cut-off of 5 or more on the BDI scale, 75/273 (28%) were assessed as depressed preoperatively (figure 2) and 60/227 (26%) were depressed postoperatively (figure 4.) There were no differences between the genotypes for those with an abnormal postoperative BDI score (p=0.935).

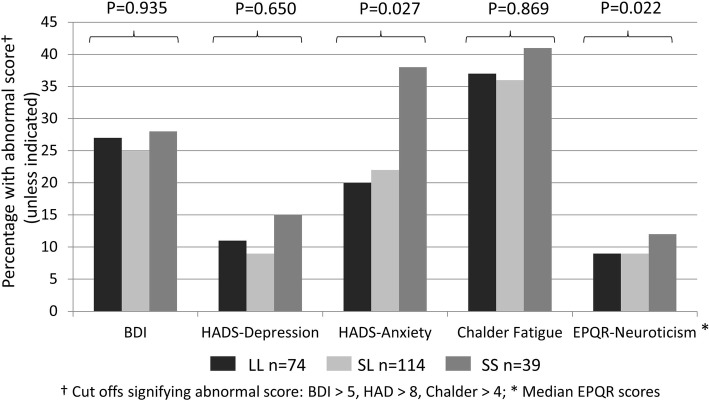

Figure 4.

Percentage of postoperative abnormal questionnaire scores by serotonin transporter gene polymorphism. BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; EPQ-R, Eysenck Personality Questionnaire; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Using logistic regression, postoperative depression was not significantly associated with genotype, when adjusting for a range of factors including preoperative depression, age, gender, previous antidepressant drug use, BMI, number of life events, number of previous operations, SES and employment status (p=0.737). However, previous antidepressant use (p<0.001) and preoperative depression (p<0.001) were predictors of postoperative depression in this model.

Both preoperative and postoperative BDI data were available for 226 patients. Of these, 38 (17%) were depressed preoperatively and postoperatively, 24 (11%) were depressed preoperatively but not after surgery, 22 (10%) were only depressed postoperatively and 142 (63%) were not depressed at either time. None of the above four groups were significantly associated with genotype status (p=0.637).

Secondary validated outcome measures

Postoperative secondary outcomes with genotype status are given in figures 4 and 5. Postoperative HAD anxiety scores were significantly worse in the SS group (38%) compared with the other groups (22% SL; 20% LL). However, none of the other postoperative scales and quality of life scores differed significantly between the three groups on univariate analysis. ANCOVA or logistic regression was used to examine the postoperative outcomes adjusting for the preoperative scores. 5-HTTLPR status was not a significant predictor in any of these analyses.

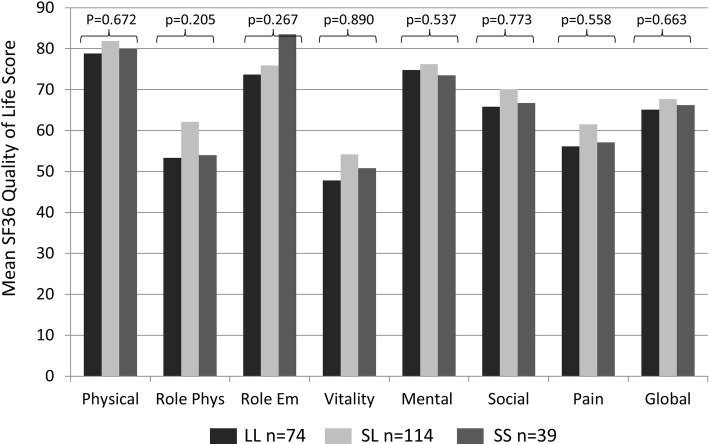

Figure 5.

Postoperative SF-36 subscale scores by serotonin transporter gene polymorphism. SF-36, 36-item Short Form Health Survey.

Patient-reported outcomes

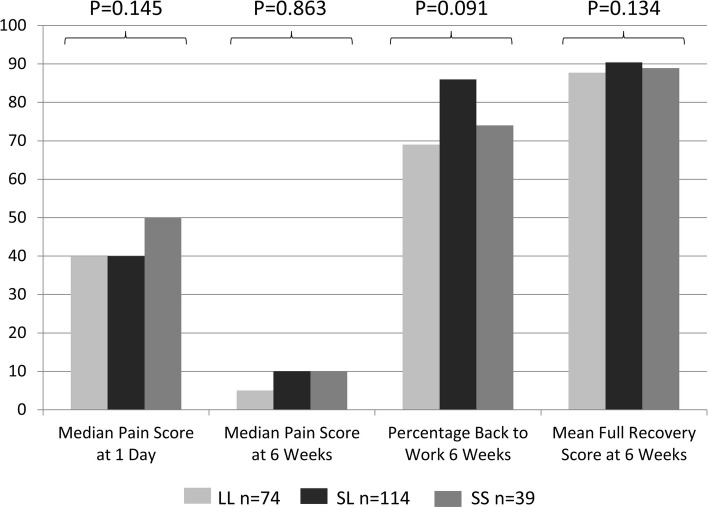

The unvalidated patient-reported outcome measures are shown in figure 6. There was no significant difference in postoperative visual analogue scale pain scores between genotype.

Figure 6.

Postoperative pain and recovery scores by serotonin transporter gene polymorphism.

At 6 weeks postsurgery, 115 of the 148 (77.7%) who were in employment had returned to work. There was no significant difference between genotype (p=0.091) and a non-linear pattern across genotypes with the proportions who had returned to work; LL (69%), SL (86%) and SS (74%). When adjusting for other factors using logistic regression, there was still no significant difference in return to employment with genotype (p=0.099).

Using the self-report scale of return to usual health, only 40% of all patients reported a full recovery (score of 100) by 6 weeks postsurgery. However, the overall mean self-report recovery score was 89% of usual health. There was no significant difference in the mean recovery scores of the three genotypes (LL=87.7, SL=90.4, SS=88.9, p=0.134) or in the proportion of patients fully recovered (LL=34%, SL=44%, SS=38%, p=0.433). When adjusting for other factors using ANCOVA, there was still no significant difference in the recovery score with genotype (p=0.854). However, preoperative depression (p=0.001), BMI (p=0.026) and postoperative pain (<0.001) were significant predictors of recovery in this model.

Significantly fewer people with preoperative depression (BDI score >5) had returned to employment (57% vs 86%, p<0.001) or made a full recovery (11% vs 44%, p<0.001) 6 weeks after surgery.

Surgical outcomes

Most patients were not routinely given postoperative clinic appointments, but 123 (44.7%) patients sought at least one unscheduled medical opinion related to the surgery. This was frequently from their general practitioner (GP) with 114 (41.5%) making at least one visit and 43 (15.6%) making two or more visits for reasons which typically included pain, wound problems, suture removal and sick notes. The SL group was less likely to see their GP (42%) compared with the SS (59%) and LL (61%) groups (p=0.019). The emergency department was attended by 18 (6.5%) patients and the ward was attended by 16 (5.8%). There was no difference between genotype groups for accident and emergency or ward visits.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper exploring psychosocial recovery after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surgeons recognise that some patients do not recover well after surgery either psychologically or in terms of prompt return to work and usual activities, despite the fact that the procedure has apparently gone well without significant complications. Most patients are not routinely followed up after such surgery, and there is a general expectation that most patients will be back to normal by 6 weeks. However, as this study has demonstrated, the proportion of patients recovering fully within 6 weeks may be notably lower than might be expected, with more than one-fifth of patients in employment failing to return to work and less than half of patients reporting that they feel fully recovered. Moreover, poorer recovery is associated with preoperative psychological morbidity, in keeping with the findings of other studies.1–3 22 This highlights a clear need to develop a better understanding of the role of psychosocial factors in patient recovery.

We found no clear evidence that 5-HTTLPR genotype is associated with risk of low mood or poor recovery after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. This may be because this operation is now relatively safe and not perceived as a negative life event. Indeed, the fact that it relieves symptoms will be perceived positively in conjunction with low levels of complications. Alternatively, it could be that psychological support throughout the perioperative period mitigates against postoperative problems (ie, that local surgical teams are already very good at it). It is also possible that the role of 5-HTTLPR in relation to psychological outcomes is minimal11 or that the low numbers of people with SS reduced power. In the candidate gene x environment interaction literature, significant results are reported in 96% of initial studies, but only 27% of replication studies.23 We observed a mixture of negative findings and some interesting positive ones, but given the number of statistical tests conducted, we cannot be confident that any represent true associations. It has been suggested that the S allele of the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism is associated with anxiety-related traits.24 While we found that preoperative antidepressant use, preoperative neuroticism scores and postoperative anxiety scores were significantly elevated in the SS group, we found that neither preoperative anxiety nor preoperative or postoperative depression scores were related to genotype. Given the relatively small sample size and the number of statistical tests conducted, these results should be treated with caution.

Preoperative assessment rarely includes psychological evaluation. With the advent of very simple and effective screening instruments that include either the short form BDI (used here) or the two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) 225 or the nine-item PHQ926 depression screening questionnaire, this is now readily possible. The finding that someone is suffering from low mood or depression may be useful information in exploring how symptoms are perceived22 and how this impacts on postoperative outcomes including coping.27 It may also help in working out what support is necessary for people undergoing operative procedures, both preoperative and particularly postoperative support. Many patients who have laparoscopic cholecystectomy do not receive routine outpatient follow-up, but a minority of vulnerable patients may benefit significantly from the reassurance that this provides, with some needing referral on for psychological therapy. Sound preoperative psychological assessment and selection of patients for appropriate and differentiated postoperative care may be an area worthy of research for improving outcomes postoperatively, psychologically and in terms of quality of life outcomes. Cost-effectiveness research in this area could be productive.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants and staff involved in the study. They also thank Professor John Sparrow and Dr John Pillmore who gave helpful genetic advice in the early stages of this project.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Collaborating members of the York Surgical Outcomes Research Team: Victoria Allgar (Hull York Medical School and Bioscience Technology Facility, York, UK), Tim Wilson (York Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, York, UK), Sophie Bennett (Leeds and York Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, York, UK), Naveed Aziz (Biology Department, York University York, UK), Danielle Collingridge-Moore(Leeds and York Partnership NHS Foundation Trust), Marcus R Munafò(MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit, UK Centre for Tobacco and Alcohol Studies, and School of Experimental Psychology, University of Bristol, York, UK), David Locker(York Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, York, UK), Ian Holbrook(York Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, York, UK), Kevin Anakwe (Leeds and York Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, York, UK), Naomi Hooke (University of York, Leeds and York Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, York, UK), Ben Alderson-Day (Leeds and York Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, York, UK), Conor Davidson (Leeds and York Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, York, UK), Heather Tomlinson (Leeds and York Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, York, UK) and Celina Whalley (Biology Department, University of York).

Contributors: BW conceived the idea with DA and both wrote the protocol, grant applications and ethics applications with support from HT and SB. BW and DA wrote the paper with support from TW and comments from all collaborators. AA and DL gave information to and consented patients, and collected genetic material. SB and DM were trial coordinators. KA and CD collected mental health outcomes. VA carried out statistical analysis. NA and CW carried out genetic analysis. TW gave surgical advice on methodology and assisted with writing up. MRM provided expert genetic advice. IH collected genetic material and kept genetic material databases. BA-D, NH and DM kept trial databases and checked and cleaned data. BW chaired the trial management group.

Funding: Thanks also to BUPA who funded the study (ISRCTN40219584; grant number BUPAF/33a/05).

Competing interests: DA and AA are laparoscopic gastrointestinal surgeons.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Leeds Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Victoria Allgar, Tim Wilson, Sophie Bennett, Naveed Aziz, Danielle Collingridge-Moore, Marcus R Munafò, David Locker, Ian Holbrook, Kevin Anakwe, Naomi Hooke, Ben Alderson-Day, Conor Davidson, Heather Tomlinson, and Celina Whalley

References

- 1.Kulik JA, Mahler HI, Moore PJ. Social comparison and affiliation under threat: effects on recovery from major surgery. J Pers Soc Psychol 1996;71:967–79. 10.1037/0022-3514.71.5.967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jowsey SG, Taylor ML, Schneekloth TD et al. Psychosocial challenges in transplantation. J Psychiatr Pract 2001;7:404–14. 10.1097/00131746-200111000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenberger PH, Jokl P, Ickovics J. Psychosocial factors and surgical outcomes: an evidence-based literature review. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2006;14:397–405. 10.5435/00124635-200607000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graziano F, Cascinu S. Prognostic molecular markers for planning adjuvant chemotherapy trials in Dukes’ B colorectal cancer patients: how much evidence is enough? Ann Oncol 2003;14:1026–38. 10.1093/annonc/mdg284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE et al. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5HTT gene. Science 2003;301:291–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilhelm K, Mitchell PB, Niven H et al. Life events, first depression onset and the serotonin transporter gene. Br J Psychiatry 2006;188:210–15. 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.009522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uher R, McGuffin P. The moderation of serotonin transporter gene of environmental adversity in the aetiology of mental illness: review and methodological analysis. Mol Psychiatry 2008;13:131–46. 10.1038/sj.mp.4002067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crawford AA, Lewis G, Lewis SJ et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of serotonin transporter genotype and discontinuation of antidepressant treatment. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2013;23:1143–50. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munafò MR, Freimer NB, Ng W et al. 5-HTTLPR genotype and anxiety related personality traits: a meta-analysis and new data. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2009;150B:271–81. 10.1002/ajmg.b.30808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clarke H, Flint J, Attwood AS et al. Association of the 5-HTTLPR genotype and unipolar depression: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med 2010;40:1767–78. 10.1017/S0033291710000516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munafò MR. The serotonin transporter gene and depression. Depress Anxiety 2012;29:915–17. 10.1002/da.22009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Risch N, Herrell R, Lehner T et al. Interaction between the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), stressful life events and risk of depression: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2009;301:2462–71. 10.1001/jama.2009.878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karg K, Burmeister M, Shedden K et al. The serotonin transporter promoter variant (5-HTTLPR), stress and depression, meta-analysis revisited: evidence of genetic moderation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011;68:444–54. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Savas S, Hyde A, Stuckless SN et al. Serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4) variations are associated with poor survival in colorectal cancer patients. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e38953 10.1371/journal.pone.0038953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamura M, Ueno S, Sano A et al. The human serotonin transporter gene linked polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) shows ten novel allelic variants. Mol Psychiatry 2000;5:32–8. 10.1038/sj.mp.4000698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev 1988;8:77–100. 10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zigmund A, Snaith P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T et al. Development of a fatigue scale. J Psychosom Res 1993;37:147–53. 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90081-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Wright L. Short form 36 (SF36) health survey questionnaire; normative data for adults of working age. BMJ 1993;306:1437 10.1136/bmj.306.6890.1437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Manual for the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPR-R) Adult. San Diego, CA, USA: Educational Industrial Testing Service, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perneger TV. What's wrong with Bonferroni adjustments. BMJ 1998;316:1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wright B, Gannon J, Greenberg M et al. Psychiatric morbidity following endometrial ablation and its association with genuine menorrhagia. BJOG 2003;110:358–63. 10.1046/j.1471-0528.2003.02199.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duncan LE, Keller MC. A critical review of the first 10 years of candidate gene-by-environment interaction research in psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry 2011;168:1041–9. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lesch KP, Bengel D, Heils A et al. Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science 1996;274:1527–31. 10.1126/science.274.5292.1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernd L, Kroenke K, Gräfe K. Detecting and monitoring depression with a two item questionnaire (PHQ-2). J Psychosom Res 2005;58:163–71. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roesch SC, Adams L, Hines A et al. Coping with prostate cancer; meta-analytic review. J Behav Med 2005;28:281–93. 10.1007/s10865-005-4664-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]