Abstract

Background

The testes are responsible for the production of spermatozoa and testosterone in man. Reliable and accurate determination of testicular volume is of great potential benefit in evaluation of patients with a variety of disorders affecting testicular growth, development and function. Ultrasonography (USS) provides a good and reliable tool for determining testicular volume when objective, accurate and reproducible measurements are required. This can be done in an easy and patient friendly manner. USS is readily available, cheap and does not involve the use of ionizing radiation; hence its suitability in neonates.

Aim

To determine the normal value for mean testicular volume in neonates using ultrasonography and to correlate testicular volume with weight, gestational age, and length as well as body mass index, so as to have a baseline reference value which will aid in prompt identification of neonates with testicular abnormalities for further evaluation and timely intervention.

Design of the Study

A multi-centre prospective cohort study

Study Setting

Radiology Departments of the University College Hospital, Adeoyo General Hospital and Eleta Catholic Hospital, Ibadan, Southwestern Nigeria.

Materials & Methods

A total of 411 healthy male neonates had testicular ultrasound performed in the labor wards and post natal wards of the University College Hospital, Adeoyo General Hospital and Eleta Catholic Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria. Testicular mean volume was obtained using the Lambert formula (length x width x height x 0.71). The statistical package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for windows version 17.0 was used to analyze the data obtained

Results

The mean left testicular volume in this study was 0.276cm3± 0.08924 while the mean right testicular volume was 0.278cm3±0.09233. The overall mean testicular volume in neonate was 0.28±0.09cm3 with no significant difference between the right and the left testes (p=0.000). There is a weak but statistically significant positive correlation between testicular volume and the birth weight, height, and body mass index but no correlation between the testicular volume and the gestational age at delivery.

Conclusion

This study showed that the mean testicular volume was 0.28± 0.09ml with no significant difference between the right and the left testes. There was a positive correlation between the birth weight, height and the body mass index and the volume of the right and the left testes but no correlation between the testicular volume and the gestational age of the neonates.

Keywords: Testicular volume, Ultrasonographic estimation, Healthy neonates, Ibadan, Nigeria

Introduction

The assessment of testicular volume has been extensively studied in recent years1. In adult males, testicular volume is measured in relation to spermatogenic activity, whereas in pediatrics, testicular volume measurement is of importance in assessing the onset of puberty or pubertal development1,2. It is also sometimes measured during evaluation of testicular abnormalities such as torsion, cryptorchidism or varicocele and is said to be related to various reproductive endocrine parameters such as serum follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), serum inhibin, inhibin B/FSH ratio and serum testosterone which are directly or indirectly related to spermatogenesis2,3.

Approximately ninety percent (90%) of testicular volume is made up of seminiferous tubules and germ cells, testicular tissue consists mainly of sertoli cells in early infancy4,5. Thus, a reduction in the number of these cells is manifested by reduction in testicular volume6. This was corroborated by Lipshultz et al7 who found that decreased testicular size, whether unilateral or bilateral, correlates with impaired spermatogenesis.

Ultrasonography (USS) provides a good tool for determining testicular volume when objective, accurate and reproducible measurements are required8. This can be done in an easy and patient friendly manner10. USS is readily available, cheap and does not involve the use of ionizing radiation, hence its suitability in neonates8.

A previous study has shown that mean testicular volume increased significantly in the first five months from 0.27 to 0.44cm3 after which the volume decreased to 0.31cm3 at approximately 9 months of age11. However, great discrepancies have been observed in the available reference charts published for testicular volume in neonates as the data were generated from transformed orchidometer measurements10.

The orchidometer was widely used for the clinical assessment of testicular volume in the doctor’s office because it is handy and less time consuming than ultrasound 10. In the use of orchidometer, not only are the testicles estimated but also the skin and the epididymis thus leading to overestimation in the testicular volume especially in small testicles where the epididymis is large10. Ultrasound on the other hand is more precise as it measures only the testicular volume11

Patients & Methods

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Ibadan/University College Hospital and Oyo State Ministry of Health ethical review committees. A total of 411 healthy male neonates had testicular ultrasound performed in the labor wards shortly after delivery and the post natal wards of the University College Hospital and that of Adeoyo General Hospital in Ibadan. Neonates whose testes were not found in the scrotum as well as preterm neonates were excluded from this study. Informed consent was obtained from the neonate’s parents after the procedure had been explained to the mother in the language they understood. Physical examination of the neonate was initially performed which included measurement of the length, weight, gestational age at delivery, and Occipito-frontal circumference (OFC) of the neonates; the data were recorded on the data form. Pregnancy and delivery history were also obtained from the mother. Male neonates recruited from the General Hospital Adeoyo and University College Hospital Ibadan were mostly immediately after the deliveries as well as those brought for circumcision between day seven and fourteen. All the subjects irrespective of center of birth were scanned between day 1 and 28 days after delivery.

Ultrasonography was performed using the Chison Ultrasonic portable machine with 7.5-10MHZ linear array transducer. Each baby was placed in the supine position on the examination table with their legs in the frog lateral position. The room was maintained at room temperature to prevent the testes from retracting. The hands were rubbed together to provide a little warmth and the gel was kept in a gel warmer at 300c.

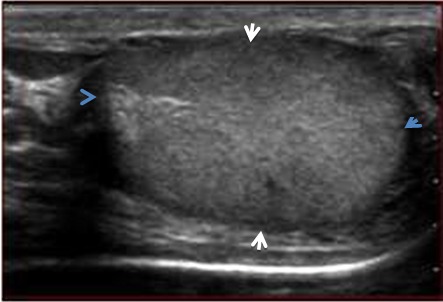

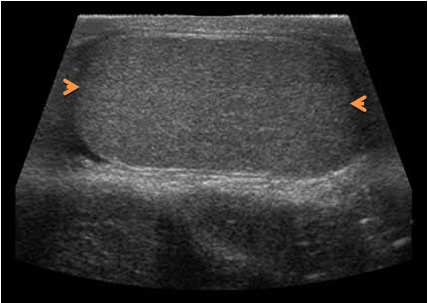

The scrotum was supported by a rolled towel placed below the scrotum to stabilize the testes and coupling gel was applied generously to minimize surrounding air interference. The testes were further stabilized by placing a finger on the median raphe of the scrotal skin before gently scanning to avoid distortion of its shape and dimension. The longitudinal plane of the testis was obtained by placing the probe on the scrotal skin over the testis and rotated until the mediastinum testis was visualized in the same plane. The image was then frozen in this position (figure 1). The transverse diameter is also measured while the testis is in the transverse position (figure 2). Testicular mean volume was obtained using the Lambert formula (length x width x height x 0.71). The statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS) for windows version 17.0 was used to analyze the data obtained.

Figure 1. Longitudinal ultrasound scan of the testis and the points of measurement of the longitudinal diameter (blue arrow heads) and height (white arrow heads).

Figure 2. Transverse ultrasound scan of the testis showing the points of measurement (brown arrow heads) of the transverse diameter.

Results

A total of 411 neonates were studied their age ranged from 1 to 27 days with a mean age of 2.00±3.13 days. The mean gestational age at birth was 39.4±1.23 weeks with a range 37-42 weeks while the mean birth weight was 3.09+0.45kg with a range of 1.9 - 4.5kg. The mean body length was 47.93+2.71 cm with a range of 36 - 56cm.The mean body mass index (BMI) was 13.41+1.80kg/m2 with a range of 9.5 - 20.74kg/m2while the mean Occipito-frontal circumference was 34.44±1.78cmwith a range of 30 - 56cm (Table 1)

Table 1. Biophysical characteristics of the neonate.

| Variable | Mean | Minimum | Maximum | |||

| Mean age of neonates | 2±2.27 Days | 1 day | 16 days | |||

| Mean Weight | 3.09±0.45kg | 1.9kg | 4.5kg | |||

| Mean Height | 47.93±2.71cm | 36cm | 56cm | |||

| Mean BMI | 13.42±1.80kgm-2 | 9.40kgm-2 | 20.74kgm-2 | |||

| Mean Occipito-frontal circumference | 34.44±1.78cm | 30cm | 56cm | |||

| Mean Gestational age | 39.4±1.23 | 37 weeks | 42 weeks | |||

The mean length, height and width of the right testicle were (0.82+0.01cm, range 0.60-1.41cm), (0.63+0.08cm, range 0.45-0.98cm) and (0.70+0.09cm, range 0.56-1.22cm) respectively, while the measurements for the left testicle were (0.80+0.10cm, range 0.54-1.13cm), (0.69+0.08cm, range 0.41-0.98cm) and (0.70+0.08cm, range 0.54-1.13cm) respectively. The mean left testicular volume was 0.2759cm3± 0.089 while the mean right testicular volume was 0.2777cm3±0.092. The overall mean testicular volume was 0.28+0.09cm3 (Table 2). The slightly higher testicular volume of the right testis was not statistically significant at p=0.298 (Table 3). Approximately 50% of the neonates had their right and left testicular volumes ranging between 0.21-0.33cm3 and 0.20-0.33cm3 respectively

Table 2. Testicular measurements of the neonates.

| Variable | Mean + (S.D.) | Range | |

| Minimum | Maximum | ||

| Mean Testicular Length | |||

| Left | 0.80±0.1 cm | 0.54 cm | 1.13 cm |

| Right | 0.82±0.01 cm | 0.60 cm | 1.41 cm |

| Mean Testicular Height | |||

| Left | 0.69±0.08 cm | 0.41 cm | 0.98 cm |

| Right | 0.68±0.08 cm | 0.45 cm | 0.98 cm |

| Mean Testicular Width | |||

| Left | 0.70±0.08cm | 0.54 cm | 1.13 cm |

| Right | 0.70±0.09cm | 0.56 cm | 1.22 cm |

| Mean Testicular Volume | |||

| Left Testis | 0.275±0.09 cm3 | 0.13cm3 | 0.94cm3 |

| Right Testis | 0.278±0.09 cm3 | 0.13cm3 | 0.92cm3 |

Table 3. Correlation of Testicular volume by birth weight, height, BMI and gestational age at delivery.

| BIRTH WEIGHT | HEIGHT | BMI | GESTATIONALAGE AT DELIVERY | |||||

| Pearson correlation | p-value | Pearson correlation | p-value | Pearson correlation | p-value | Pearson correlation | p-value | |

| RIGHT TESTICULAR VOLUME (CM3) | 0.249 | 0.000 | 0.172 | 0.000 | 0.143 | 0.002 | 0.056 | 0.128 |

| LEFT TESTICULAR VOLUME (CM3) | 0.255 | 0.000 | 0.164 | 0.001 | 0.163 | 0.000 | 0.065 | 0.093 |

Bilaterally, there was statistically significant correlation between the testicular volumes and birth weight, body mass index as well as the height of subjects at p=0.000,0.004 and 0.000 respectively on the right and p=0.000, 0.000 and 0.001 on the left respectively. However, the strength of correlation was weak with Pearson correlations of 0.249, 0.143 and 0.172 for the right testis and 0.255, 0.163 and 0.164 for the left testis respectively. There is no statistically significant association between the testicular volumes and gestational age at delivery with p- values of 0.128 and 0.093 for the right and left testes respectively. The mean difference between the right and left testicular volumes is 0.00185 (p =0.770) which implies that there is no significant difference between the right and left testicular mean volume (Table 3).

There is a weak correlation between testicular volumes and height, and the coefficient of determination R2 accounts for 6.2% and 6.5% on the left and right respectively. A positive correlation between birth weight and both right and left testicular volumes was found hence neonates with higher birth weight had high testicular volumes.

Discussion

The increasing public awareness and need for qualitative care as well as the ever increasing role of technology in modern day medical care has placed a huge responsibility on imaging practitioners. Among the many challenges facing the radiologist and/or urologist in fertility care today is early and accurate diagnosis of testicular anomalies as well as prognostication of testicular anomalies which may be difficult12.

Measurement of testicular volume in children is an important tool in assessing the status of the testis in disease states such as undescended testis, orchitis, varicoceles and torsion so that early and appropriate intervention could be instituted. In adults, testicular volume measurement is done in addition to semen analysis and measurement of serum hormones as an integral part of evaluating male infertility because testicular volume directly corresponds to semen profile13. This in effect is a strong reason for the establishment of an acceptable cut-off value for testicular volume, beyond which further evaluation becomes imperative. The non-invasiveness of ultrasonography and the fact that it is devoid of radiation allows for repeated monitoring of these disease entities14.

In this study, the mean testicular volume was found to be 0.28±0.09 (p=0.000). The right testicular volume was 0.278 cm3±0.092 while the left testicular was 0.276 cm3±0.089. The slightly higher testicular volume on the right was not statistically significant at p=0.298.

Kuijper et al used an Aloka SSD-900 ultrasound machine with a 7.5MHZ linear transducer to study the testicular volume in 344 boys from different ethnic groups and found no difference between the left and right testicles and between the various ethnic groups9. In their study, the mean testicular volume was found to be 0.27cm3 at birth which corroborates the finding in this study9. This finding is at variance with findings from Kiridi et al 5 in adult Nigerian males in which there was a significant statistical difference between the volume of the right and left testes (p=0.000). The slight reduction in the testicular volume on the left could be explained by the fact that the pampiniform plexus of veins are more prominent on the left resulting in an increased temperature in the left testis with subsequent reduction in spermatogenesis and testicular volume on that side15. The pampiniform plexus of veins may not yet have developed in the neonate which could explain the similar volume of the right and left testes in neonate in this study.

In this study, the gestational age at delivery did not show any correlation with the volume of the right testis, the left testis and the mean testicular volume. This finding is similar to that of Kiridi et al5, Beres et al20 and Tajima et al21. In their studies on adult male population they established that the testis achieved its maximal size by 18 years and remained so until 80 years after which it decreased in size1,16,17.

There was statistically significant correlation between the body length of the neonates and the volume of the right and left testes and the mean testicular volume. The finding was in keeping with the work of Sobowale et al13 involving twenty adult Nigeria men in whom total testicular volume was estimated using a metric tape and a Vernier caliper. There was good correlation between total testicular volume and height (p<0.001, r= 0.96) of the subjects.

Our study also showed significant correlation between the weight of the neonates, both right and left testicular volumes and the mean testicular volume. This finding was in keeping with findings reported by Sobowale et al13.

We found that the right and left testes were of equal size in 40% of the neonates while in others the right testes were slightly larger. Positive correlation was found between testicular volume , birth weight and height and this corroborated well with the study reported by Wikramanayake who measured testicular size in 200 Sinhalese men aged 21-31years18. The testes were of equal size in 75% and the right testis was larger in 20% of the men. There was also a significant correlation between testicular size and body weight (p<0.05) and a significant correlation between right testis size with arm span (p<0.01)18.

However in this study, there was a weak positive correlation between testicular volumes and body weight, height and body mass index. This substantiated the study reported by Jong et al8 in Korea where testicular volume of 1002 young adult Korean men were measured for length, width and thickness8. Testicular volume was found to have weak direct correlation with body weight, height and body mass index21.This finding was also supported by the work of Aribarg and co-workers who studied 307 Thai male volunteers whose wives were in early pregnancy15. Ninety percent of the subjects had testicular volumes which related to body weight, height and the body mass index as well as to the sperm count15.

The gestational age and BMI showed a persistent and poor linear correlation with the volume of the right and left testes. This is also confirmed by Aribarg et al15. However, the birth weight showed a positive correlation with both the right and the left testicular volumes15. Although this study did not correlate the ultrasound volume with orchidometer, but the orchidometer tended to overestimate the true volume of the testis especially in neonates in whom the epididymis is relatively large10,11. Ultrasound on the other hand is more precise as it measures only the testicular volume10,11,11.

Although other workers have used Prader orchidometer, there is still no consensus on its accuracy and reliability. While some think it is neither accurate nor reliable, Schiff et al19 reported that orchidometer measurement correlated closely and significantly with ultrasound measurement (formula L x W x H x 0.71)19. In their study the mean orchidometer testicular volume in adults was 18.3ml on the right and 16.9ml on the left, and did not differ significantly from the mean ultrasound volume (18.4ml on the right and 17.1ml on the left). Other studies have also showed a strong correlation between orchidometric and ultrasonic measurements, although orchidometer often overestimated the testicular volume relative to ultrasound 8,10,18.

A study performed by Fok et al in China reported a weak albeit statistically significant correlation between gestational age, length, weight and testicular volume20.

Paltiel et al in their work on canine testes reported that the most accurate of the ultrasound formulas was formula 1 (L x W x H x 0.71)21. In their work, formula 2 (L x W x H x 0.52) underestimated by (31%) and formula 3 (L x W2 x 0.52) by (11%) but they noted that formula 3 caused the least mean bias. Hence, formula 1 was used in this study.

Rivkees et al in their earlier work in 1987 when the new formula was not an issue used only formula 2 on 10 calves and 9 dogs with a simulated scrotum22. They found that this formula had an accuracy of 4.6% ± 1.6%. This is however not consistent with any of the studies mentioned earlier. This may be because they worked on scrotum that was simulated by double sheep skin.

Counseling by the nursing staff and health works aided the participation of the neonates in the study. Male neonates were also often brought back to the hospital within 7 days of birth for circumcision which is a common practice in Nigeria irrespective of religious inclination. This afforded us the opportunity to recruit male neonates into the study.

Conclusions

This study showed that the mean testicular volume was 0.28± 0.09ml with no significant difference between the right and the left testes. There was a positive correlation between the birth weight, height and the body mass index and the volume of the right and the left testes but no correlation between the testicular volume and the gestational age of the neonates.

Acknowledgment

We wish to express our profound gratitude to the management of Adeoyo General Hospital and Eleta Catholic Hospital, Ibadan for their cooperation.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Grant support: None

References

- 1.Kiridi EK, Nwankwo NE, Akinola RA, Agi CA, Ahmed A. Testicular volume in adults. J of Asian scientific research. 2012;2:45–52. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guyton AC, Hall J. Reproductive and hormonal functions of the male. In: Guyton AC, Hall JE, editors. Medical physiology. 10th Philadephia: WB Saunders ; 2004. pp. 916–917. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costabile RA, Skoog RM. Testicular volume assessment in adolescents with varicocele. J of Urol. 1992;147:1456–1457. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37561-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Setchell BP, Hertel TSO. Postnatal testicular development, cellular organization and paracrine regulation. Endocr Dev. 2003;6:24–37. doi: 10.1159/000069295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takihara H, Consentino MJ, Sakatoku J, Cockett ATK. The significance of testicular size measurement in andrology: Correlation of testicular size with testicular function. Int J Urol. 1987;137:416–419. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)44053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jong WL, Jong YB, Ski M. Testicular volume in Korean young adult men as measured by ultrasound. Relationship with body mass index. Korean J of Urol. 2009;50:591–595. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lipshultz L, Corriere J. Progressive testicular atrophy in the varicocele patient. J Urol. 1977;117:175–176. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)58387-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dogra VS, Gottlieb RH, Oka M, Rubens DJ. Sonography of the scrotum. . Radiol Society of North Am. 2003;227:18–36. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2271001744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuijper EAM, van Kooten J, Verbeke JI, van Rooijen M, Lambalk CB. Ultrasonographically measured testicular volumes in 0- to 6-year-old boys. Human reproduction. 2008;23(4):792–796. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taskinen S, Taavitsainen M, Wikström S. Measurement of testicular volume, comparison of three different methods. J of Urol. 1996;155:930–933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Behre HM, NaHsan DNE. Objective measurement of testicular volume by ultrasound, evaluation of the technique and comparison with orchidometer estimates. Intl J of Androl. 1989;12:395–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.1989.tb01328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahony BS, Nyberg DA, Hirsch JH, Petty CN, Hendricks SK, Mack LA. Mild idiopathic lateral cerebral ventricular dilatation in-utero, Sonographic evaluation. Radiology. 1988;16:715–721. doi: 10.1148/radiology.169.3.3055035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sobowale OB, Akinwumi O. Testicular volume and seminal fluid profile in fertile and infertile males in Ilorin, Nigeria. Int J of Gynecol and Obstet . 1989;28:155–161. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(89)90476-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rundle AT, Sylvester PE. Measurement of testicular volume. Its application to assessment of maturation, and its use in diagnosis of hypogonadism. Arch Dis Child. 1962;37:514–517. doi: 10.1136/adc.37.195.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aribarg A, Kenkeerati W, Vorapaiboonsak V, Leepipatpaiboon S, Farley TM. Testicular volume, semen profile and serum levels of fertile Thai males. Int J of Androl . 2008;9:170–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.1986.tb00880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beres GY, Czeisel E. Testicular volume variation from 0 to 28 years of age. . Int J of Urol and Neph . 2007;21:159–167. doi: 10.1007/BF02550804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tajima M. Testicular measurement by test size orchidometer. Acta Urological Japonica. . 1988;34:2013–2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wikramanayake E. Testicular size in young adult Sinhalese. Int J of Androl. 2008;18:29–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.1995.tb00635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schiff JD, Li PS, Goldstein M. Correlation of ultrasonographic and orchidometer measurement of testicular volume in adults. British J of Urol Int . 2004;93:1015–1017. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2003.04772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fok TF, Hon KL, So HK, Wong E, Ng PC, Chang A, Lau J, Chow CB, Lee WH. Hong Kong Neonatal Measurements Working Group. Normative data of penile length for term Chinese newborns. Biol Neonate. 2005;87:242–245. doi: 10.1159/000083420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paltiel HJ, Diamond DA, Di Canzio J, Zurakowski D, Borer JG, Atala A. Testicular volume, comparison of orchidometer and US measurements in dogs. Radiol. 2002;222:114–119. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2221001385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karmazyn B. Scrotal Ultrasound. www.ultrasound. the clinics.com 2010;5:61–74. [Google Scholar]