Abstract

Men who have sex with men (MSM) and other same-gender-loving men continue to be disproportionately affected by HIV and AIDS, particularly among the Black population. Innovative strategies are needed to support the health of this community; however, public health efforts primarily approach MSM as a monolithic population erasing the diverse identities, practices, and sexualities within and beyond this category. To better understand diversity within MSM in a geographic region with the largest proportion of Black Americans in the U.S. and among the most heavily affected by the epidemic, the Deep South, we conducted four focus groups (n=29) with Black men who reported having sex with other men residing in Jackson, Mississippi. Results suggest multiple overlapping usages of MSM as identity and behavior, reflecting internalization of behavioral categories and co-creation of identities unique to the Black community. These narratives contribute to the literature by documenting the evolving understandings of the category ‘MSM’ among Black men to reflect intersections between race, socioeconomic status, sexual behavior, sexuality, subjectivities, and social context. Findings suggest the current monolithic approach to treating MSM may limit public health efforts in developing effective HIV prevention and promotion programs targeting same-gender-loving Black men in the Deep South.

Keywords: African American, MSM, identities, HIV, United States

Introduction

In the United States, men who have sex with men (MSM) have been disproportionately affected by HIV since the start of the epidemic, and Black MSM (BMSM) are the most affected compared to other racial/ethnic MSM groups (CDC, 2012). The current status of the epidemic, however, cannot be understood solely in terms of racial and gender difference, but rather geographic concentrations highlight that the largest burden of HIV is in the Southern United States (Nunn et al, 2014; Oster et al, 2011). For example, Mississippi ranks second in states with the greatest proportion of Black residents and among the top 10 states in HIV infection rates (Mississippi State Department of Health, 2010). In 2010, close to 80% of all new cases of HIV were among Black Americans in the state (Mississippi State Department of Health, 2010), and new infections increased by 38% from 2004–2005 to 2006–2007 among young BMSM in the Jackson, Mississippi metropolitan area (CDC, 2009). However, the previously understood risk factors and demographic characteristics do not explain existing disparities among BMSM (Millett et al, 2012; Millett et al, 2007). As such, there is an urgent need to assess socio-cultural factors and local realities to better understand key determinants influencing the high HIV rate and maintenance of HIV prevalence among the BMSM community.

To understand risk and vulnerability to HIV for Black men, an acknowledgement of the intersections between race, class, gender, sexuality, and power are necessary to inform their lived reality. A keen starting point is with the category BMSM. Scholars critiquing the term 'MSM' highlight that such a broad term erases diverse identities and decontextualizes same-gender sexual behavior, and the repercussions for culturally relevant prevention and promotion efforts (Young and Meyer, 2005; Boellstorff, 2011). Similarly, Petchesky (2009) critiques the term “sexual minority” for codifying potentially problematic assumptions about what is ‘normal’. These limitations may be particularly salient for Black men and their vulnerability to HIV. As a push beyond MSM, or BMSM, the present paper uses local terms derived from the community, alongside the term same-gender-loving (SGL) in efforts to minimize minoritizing discourse that reinforce the hierarchical division between majority (‘normal’) and minority (‘abnormal’) groups (Young and Meyer, 2005; Petchesky, 2009; Parks, 2001). Adopting an intersectionality perspective furthers attention to category construction by highlighting the complex interactions between race, gender, class, and sexual identities (Dworkin, 2005; Bowleg, 2012). Intersectionality theory posits that identification with more than one social group is qualitatively unique and intersectional, not additive, and that intersecting identities at the micro-level of individual experience reflect interlocking systems of inequality at the macro-level. Thus, membership of different identity groups can lead to differing behavioral health consequences (Bowleg, 2008; Crenshaw, 1995).

Recent discussions of same-gender-loving Black men on the down-low (DL) have problematized the use of DL in relation to Black sexuality suggesting that the term furthers the narrative that Black men are dangerous, sexual predators who have double lives, secretly having sex with other men, while placing their girlfriends or wives at risk for HIV (Ward, 2008; Watkins-Hayes, 2014). Stigma attached to DL may stem from the co-opting of DL by public health in relation to HIV infection and the pressures to adhere to traditional expectations of Black masculinity (McCune, 2014; Fields et al, 2015). In extension, the false notion that DL is unique to same-gender-loving Black men and does not occur in other races, including White men reinforces these stereotypes that serve to further stigmatize DL same-gender-loving Black men (Ward, 2008; Robinson and Vidal-Ortiz, 2013).

Socially constructed identities and subjectivities within the MSM category among Black men can also be viewed as sexual identities and practices that ebb and flow over time, situational contexts, and within power relations. With regard to HIV vulnerability, among young urban same-gender-loving Black men expectations of hypermasculine and anti-feminine behavior, and failure to meet cultural standards of masculinity, influenced feelings of social isolation, low self-esteem, and low awareness of HIV prevention messages (Fields et al, 2015). In extension, some scholars have sought to provide analytic groups to enhance HIV prevention efforts among same-gender-loving Black men, suggesting typologies of HIV testing patterns, characterized by sexual identity and behavior (Hussen et al, 2013). Particularly relevant to same-gender-loving Black men, Weber's (2001) research showed that viewing an individual's lived experiences at the intersections of race, class, gender and sexuality reveals influential relationships of hierarchy and interlocking systems of inequality. Interrelations between variation in identities at the micro-social psychological level and the broader society's multiple interlocking race, gender, class, and sexual orientation systems of oppression may further reveal group differences in HIV vulnerability within the same-gender-loving Black male community (Collins, 1991).

Given the HIV and AIDS burden among same-gender-loving Black men and specifically same-gender-loving Black men in the Deep South, there is a need to better understand the multiple intersecting identities and practices within the Black ‘MSM’ category. Knowledge of diverse and intersecting identities, subjectivities and labeling practices can better inform public health research, HIV/AIDS services and intervention development. Accordingly, this paper explores the diversity of sexual identities and subjectivities within the MSM category and how realities of race, sexuality, and power contribute to HIV sexual risk behaviors for same-gender-loving Black men in the Deep South. The aims of the study were to explore: (1) how same-gender-loving Black men in Jackson, Mississippi socially construct and define identities and labels within the broad category of MSM; and (2) how these identities and labels relate to HIV sexual risk and testing behaviors among this population.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Between July 2014 and August 2014, 29 same-gender-loving Black men participated in four focus group sessions in Jackson, Mississippi. All participants were part of a larger multisite study, the CDC-funded Minority HIV/AIDS Research Initiative (MARI) that examined interpersonal, intrapersonal, and environmental factors associated with HIV/STI infection among same-gender-loving Black men in the Southeastern United States. Full study details are reported elsewhere (Hickson et al, 2015). In brief, eligibility was restricted to participants who self-identified as African American, assigned male sex at birth, identified as a cisgender man, 18 years old or older, reported having had sex with a man in the past six months, and lived in Jackson.

Recruiters contacted active MARI participants who expressed interest in future studies via telephone or text message. All men who indicated interest were scheduled to a session. All sessions were hosted after-hours in a private space at a community-based LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender) health clinic. Prior to study commencement, participants provided informed consent. Prior to group-based discussion, participants completed a demographic survey. Focus group sessions lasted between 60 to 90 minutes and covered four domains: types of identities and labels within the same-gender-loving Black male community in Jackson, Mississippi; dynamics of interaction between identity groups; condom negotiation among identity groups during anal intercourse; and HIV testing behaviors among identity groups. All participants were provided a $35 gift card, condoms and water-based lubricant. The Mississippi State Department of Health, Tougaloo College, and Sterling Institutional Review Boards approved all study procedures.

Analytic Approach and Data Analysis

Focus groups were employed to identify identities within the Jackson same-gender-loving Black community, and to illuminate social norms and patterns regarding identities, and HIV sexual risk behaviors within this community (Hussen et al, 2013; Allen, 2005). This allowed exploration of subjectivities, revealing how same-gender-loving Black men manage their own sexual, gendered, racial, and class memberships through discussions about identities and labels within the 'MSM' category and HIV risk.

Focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Analysis was guided by intersectionality theory (Crenshaw, 1995), and study aims. The analytic framing revolved around social category memberships and power relations between groups and social roles in relation to the identities and labels within the MSM category. Qualitative data were analyzed for saturation of focus group patterns and themes by two independent coders, trained in qualitative data analysis (Weiss, 1995; Stewart, Shamdasani, and Rook, 2007). Coders analyzed the data through: (a) highlighting excerpts from transcripts, (b) developing codes based on excerpts, (c) linking codes to excerpts, and (d) developing and linking memos to coded excerpts. Coders then reviewed each others' codes and coded excerpts. Themes that emerged from the coded excerpts within and across focus group transcripts were identified. All analyses were conducted using an online qualitative research software program, Dedoose (Version 5.2.0) (http://www.dedoose.com).

Results

Among the 29 participants, ages ranged between 19 and 42 years (M=24.8, SD=5.52). The majority grew up in Mississippi (79%) and 79% reported their sexual orientation as gay or homosexual, while 17% self-identified as bisexual and 3% as other. Across focus groups 37 identities and labels associated with the MSM category were identified (See Table 1). When asked about a distinction, if any, between behavior and identity, participants generally felt that behavior and identity frequently overlapped. For instance, performing a sexual role, such as a top, bottom, and versatile, was considered sexual behavior. Nonetheless, for some, sexual behaviors were interwoven with their sexuality, as well as, a key aspect of their sexual identities. When asked about whether there were differences between labels and identities, participants felt that labels were generally identities imposed upon them by others, from within and outside their community, and the majority were described as being negative (e.g., floor punk and punk). Few identities emerged that were considered positive, including beat girl and professional.

Table 1.

Illustrative Quotes from Focus Group Narratives of Terms Associated with ‘MSM’ among same-gender-loving Black men in Jackson, Mississippi

| Identity/Label | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Top/Bottom | "A top penetrates. A bottom takes it." [FG2] |

| Fudge packer | "…a behavior of sex…pack fudge… So the top in which penetrates the bottom when you’re pounding him." [FG4] |

| Verse-top | "…boys are very funny because we may top you and bottom for somebody else." [FG4] |

| Verse-bottom | "Ain’t no more straight tops and straight bottoms." [FG4] |

| Power-bottom | "a person that can take the whole Interstate 55 up their anus. That means they don’t have a hole. They done lost the grip." [FG1] |

| DL | "And DL, or down low is from my understanding a man who’s more conservative, really conscious about…how people are perceiving him and he doesn’t want to be perceived as a part of the homosexual community." [FG2] |

| Trade | "…dudes who are usually willing to do sexual things very discretely for a trade off of something, whether it be money, a place to stay, you know, support in some type of way." [FG2] |

| Homo thug | "So, homothug would be part of this DL/Trade, ultra masculine group." [FG3] |

| Jock | "…the ones that go to the gym all the time, and those people they’re very desirable." [FG1] |

| Professional | "Pretty much everyone that’s career oriented.” [FG1] |

| Floor punk/Floor sissy | "…the gay people that sleep on the floor of somebody else’s house. It’s the closest thing to homeless. Like, they’ll circulate from friend to friend." [FG1] |

| Club head | "You know the people that you see in the club every time you go." [FG1] |

| Masc | "Masc is masculine." [FG2] "More aggressive…Controlling…You can't be dating anyone else, but they can be messing with God knows who else." [FG 3] |

| Femme | "Femme [means]…really gay." [FG2] |

| Daddies/Sugar daddies | "Older men who wanna take care of younger guys…some people are smart enough not to allow the daddies to control their acts, but then some people need the money…like the floor punks." [FG1] |

| Punk | “I think as it relates to Jackson, punk kind of takes every idea of stereotypical of a homosexual in the South or a Black homosexual and puts it under one label… Lazy…very promiscuous, very feminine, bummish, doesn’t work really. At the club every weekend.” [FG2] |

| Sissy | "…more sort of a conservative, but flamboyant guy." [FG4] |

| Beat girl | “…they work/walk the beat…So beat girls and street walkers can kinda go together.” [FG1] “They’re the pretty girls…guys that will come to the club in makeup but will wear regular guy clothing. And it’s no hair or anything; it’s just a pretty face. It's masculine dress.” [FG1] |

| Bitch | "A label or a taunt even. Same way another female will call another female a bitch and mean it in a bad way." [FG4] |

| Drag queen | "Female impersonation… some people just do it for the clubs as a career and some do it in real life." [FG1] |

| Butch queen | "They are like feminine guys, but they’re more masculine. They wear the beard…the regular male hair like a fro or bald head but they have on like full make-up." [F G1] |

| Stunt queen | "It comes from stunt which is slang for trying to be more than what you are…someone who tries to identify something to which they really don’t ascribe." [FG1] |

| Church queen | "When they are at church most of them will not say they are gay or anything, but they are the most flamboyant human beings in the church. Their identity is tied to their religious affiliation… They don’t express their sexuality even though everyone in church knows (through) their actions and gestures… Like the tambourine player, how they stereotype that to be like the only gay male in church." [FG1] |

| Fag/Flaming faggot | "Words from transvestite to flaming faggot those ain’t no positive words at all you gone get to fighting if you say that." [FG4] |

| Homo | "The abbreviation of homosexual is offensive." [FG2] |

| J-setter | "It’s a group of male dancers…within the MSM community. It’s a certain style of dance that is made popular by Jackson State j-setters… a group of girls, who perform certain distinctive moves that are indicative of that group." [FG1] |

| Fish | "…someone who’s extremely feminine probably to the point where they could probably fool you into thinking they are a real woman, but not necessarily a transgender." [FG2] |

| House boy | "…they are guys that have sex just to stay at somebody’s house and clean up and have sex with them just to stay there." [F G1] |

| Porn star | "They make gay porn…and they do it for the money." [FG1] |

| Street walker | "…a prostitute…that dress-up as a woman in drag…" [FG1] |

| Powder head | "Cocaine…They come together and do the same kind of drugs and they party a different kind of way but in the same venue as others." [FG1] |

| Pill popper | "[Guys who are also high on]…codeine, xanax, umm yeah molly. Codeine, molly, crazy stuff. And anti depressants." [FG1] |

| Thirsty/THOT | "…THOT, and thirsty are terms that just very openly sexual individuals who have no boundaries. THOT… An acronym for 'That Hoe Over There'…individuals that basically anything goes." [FG4] |

| Trannies | "…they classify themselves as trannies you know like Carmen Carrera, got up, she don’t like to be labeled as a trannie, but technically she is because she’s transgendered. But trannies just a short term word for it… but to her its offensive." [FG4] |

| Trans | "…trans, transgendered, transgendered men are a part of the MSM lifestyle because technically they have not had a gender reassignment are still men sleeping with men, other enhancements to live their life as a female." [FG4] |

| Transvestite | "…some people consider transvestites as those who haven’t gone through the surgery but they’re still going around as a female. But they’re still men." [F G2] |

FG is an abbreviation for Focus Group

Sexual and social desirability hierarchy

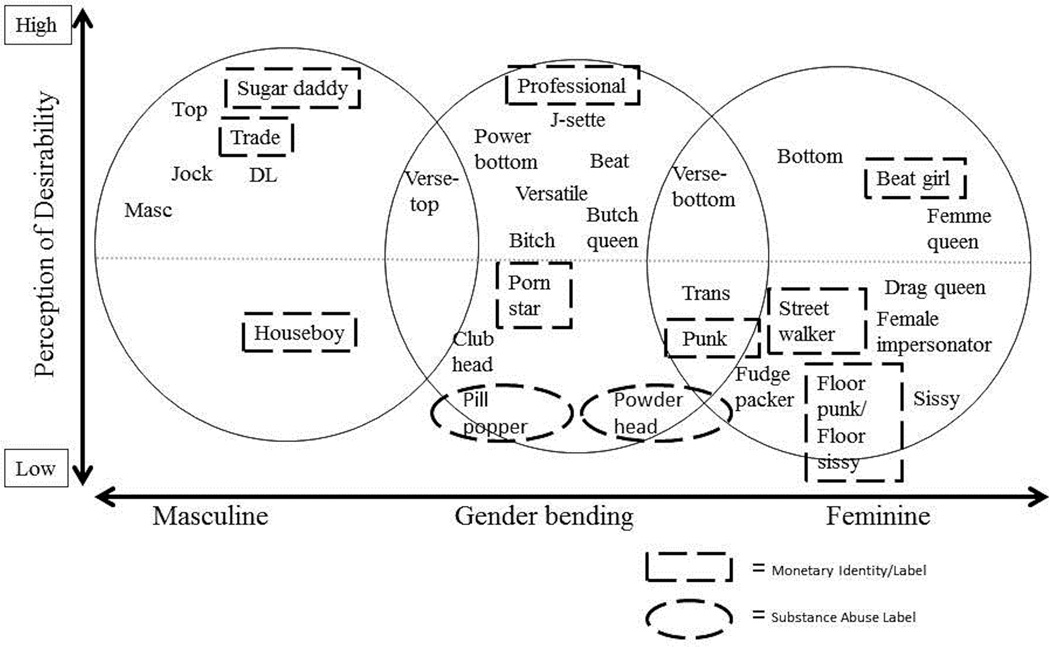

Participants described a hierarchy of sexual and social desirability among sub-labels within the MSM category. The most sexually desirable strata encompassed labels characterized by masculine appearance, mannerisms, and/or talk (e.g., DL, trade, jock), and the most socially desirable strata were labels with high socioeconomic status (e.g., professional). Conversely, the lower strata were typically described as gender bending or feminine characteristics (e.g., floor punk, punk, sissy, trans), lower socioeconomic status (e.g., floor punk, punk, street walker, porn star), and drug use (e.g., powder head, pill popper) (See Figure 1). Across narratives, the intersection of social membership categories (e.g., race, gender, class, sexual behavior) and the power relations between groups were reflected in the hierarchical construction of identities and labels. Labels used within this community were reported as having unique social meanings tied to recognition and respect both within and beyond their immediate community. One participant discussed the intersection between gender, power, and desirability:

"Sometimes we just label each other in order to climb the hierarchy… and then on top of that when you get to the outside world, the world is like (also) labeling (us)… and most times the labels are negative. Like if I'm considered a queen, then I'm disrespected by a top because the top feels like this is a guy that thinks that he is a woman, but that queen might not think he is a woman. He's just feminine, and so the top sees him (the queen) as, you know, nothing, or he (the top) is more powerful in a sense." [FG1]

Figure 1.

Conceptual Mapping of Identities and Labels Associated with Understandings of MSM in Jackson, Mississippi

The above quote highlights the underlying topography of power differentials based on gender that parallel existing social inequities. For example, "sometimes we just label each other in order to climb the hierarchy" suggests intention and that labels are not given passively. Linking to the intersection between gender and power, the section, "He's just feminine, and so the top sees him (the queen) as, you know, nothing, or he (the top) is more powerful in a sense" speaks to the ways in which the already existing ordering of masculinity at the societal level is presented in a different form, where dominant (masculine top) and subordinate (feminine queen) positions are viewed at the intersection of gender and sexual role positions. As such, the majority of participants highlighted that masculine identities were perceived as more sexually desired than feminine identities because they were more controlling, dominant and aggressive.

Perceptions of desirability were particularly relevant to discussions regarding HIV prevention efforts. When discussing narratives of sexual intimacy and condom negotiation, participants reported more masculine associated labels as having the ‘upper hand’ in facilitating the occurrence of the sexual event and negotiating HIV prevention (e.g., condom use). Nonetheless, participants also stated that sex “just happens” and that factors beyond perceived masculinity impact condom use. For example, when discussing sex between two bottoms, participants combined labels such as “professional-bottom” or “j-setter-bottom” to further delineate economic standing [FG4]. Overlapping labels allowed participants to express their intersecting economic status and sexual role position identities and labels, which additionally were described as influencing a partner’s ability to negotiate condom use or non-use.

The descriptions of power dynamics within this perceived hierarchy were also linked to class characteristics. Labels associated with more economic stability were also described as more sought after as a sexual partner and labels associated with economic disparities were intertwined with perceptions of HIV risk. When asked what other factors influence condom use, participants discussed drug use and engagement in a sexual economy, such as, exchanging of sex for money and basic necessities (e.g., food and shelter). The use of sex to obtain money, drugs, etc. was perceived as socially undesirable and in extension sexually undesirable. As described by participants, sexual commodification is prevalent in the lower stratum of the social and sexual hierarchy. Sub-labels used to describe these practices, and in extension identities, included powder heads, pill poppers, beat girls, street walkers, houseboys, floor punks, and porn stars. The accumulation of multiple undesirable characteristics can be additionally evidenced through the intersection of race and sexual identities with (low) economic stability and (high) drug use statuses. Across discussions, economically marginalized same-gender-loving Black male subgroups were perceived to be at higher risk for HIV infection and less likely to be able to negotiate condom use during a sexual encounter. For instance, when participants were asked which groups needed the most immediate public health interventions, they identified street walkers and substance abusers (powder heads and pill poppers).

"I would say the ones who like y'all said earlier that situational sex, those who use sex in exchange for some other service. Those are the ones who probably engage in more impulsive behaviors I would assume, or the ones with impaired judgment…Those that need something." [FG1]

Gendered sexual scripts and hypermasculinity

Several participants mentioned an expectation for gay coupling to mimic heterosexual norms: comprised of a masculine-top/feminine-bottom dyad. Descriptions also detailed expectations regarding appropriate ways to have sex and to display masculine behavior. These gendered sexual scripts highlighted masculine/feminine power dynamics but additionally intersected with culture, race and class. For example, the interrelationships between gender role expectations and Black sexuality, homophobia, living a double life, engaging in unprotected anal intercourse, and not getting tested were reflected in the following quotes from participants across three focus groups:

"…Historically, African American men are seen as hypermasculine and that's a culture that's been bred to be African American masculine men, you have to be hypermasculine…" [FG1]

“… I feel like when homosexuals were like shunned by like society, that forced them into the shadows and into the dark doors, and the undercovers, you know, sneaky, you gotta be in, you gotta be out. So, the whole preparation and the whole thinking about oh we need to be using protection, it kind of goes out of the window if y'all meeting up outta nowhere and randomly doing it because you don't want everybody to know.” [FG2]

"…one of the reasons why they're [referring to DL and trade] so afraid to come in [to a clinic] because they don't want to know because if it is that they have something, the girl's gonna be wanting to know who you've been messing with, and then that's when problems arise." [FG3]

Focus group participants also described bottoms as more promiscuous, a perception also noted to be prevalent in the same-gender-loving Black male community. Combined with the sexually desired and highly sought after masculine tops, bottoms become at high risk for HIV infection.

"But I know for the bottoms, they're typically more promiscuous. And so if I'm the bottom and I'm chasing after you and my top doesn't want to use a condom, I want to have sex with my top so we're not going to use a condom because I still want to have sex." [FG2]

Narratives of hypermasculinity specific to the Black community emerged as a hegemonic masculinity script facilitating the strict policing of feminine behaviors, mannerisms, and talk that occurs both outside and within the same-gender-loving Black male Jackson community.

"To be African American men, you have to be hypermasculine which means you can't be anything remotely gay. If you took a risk, you're seen as feminine. If you talk a certain accent, if you don't talk Black and you don't talk country, if you talk with a certain professional air [of confidence] then they [define] you as feminine. If you wear pants that are at your waist, you're seen as feminine. So being hypermasculine is what's desired and that's very relative and very specific, I think to Black MSMs." [FG1]

Discussions of hypermasculinity and gendered expectations were linked to expected sexual roles. Participants frequently noted that the association with hypermasculinity and role was often a stereotype that did not accurately represent intimate encounters. Participants stated that though stereotypes helped structure the hierarchy of sexual desirability, the reality of sexual role practices that occurred during sex were flexible. Beyond the bedroom, these stereotypes influence access to HIV prevention services for DLs. For example, when asked about which same-gender-loving male sub-groups would be least likely to access medical care, participants stated:

"Trade…DL. Because ain't that how women get STDs, because of DL? You know they don't get checked out…They don't want to be seen there….they not going to go to any clinic until it’s an extreme, and then they going to the hospital. And the reason I say that is because (DL and), trade feel as if they're exempt…because like I said, those that are sleeping with men and women think that they're exempt from anything happening to them.” [FG4]

Across focus groups, participants perceived that DLs were least likely to get tested for HIV and some participants additionally noted that unprotected anal intercourse legitimized DL masculinity. Participants also discussed parallels between DLs and trades getting tested for HIV and heterosexual men getting tested for prostate cancer—noting that they think that they are "too real of a man" and "stubborn" to seek a health professional. Black men are supposed to "be strong all the time" [FG2]. Moreover, when asked why trades and DLs are less likely to use condoms during sex, focus group participants stated:

"And if you’re tryna imitate what an everyday man is as a trade or a DL, you’re probably like it's ok not to have sex with a condom because my cousins do it or my uncles do it and everybody else, all the dudes I know do it. That’s what I’m tryna be like." [FG2]

Paradox of ‘DL’

As highlighted in Theme 2, the term DL is not only a term but also a label, which embodies gendered sexual scripts, hypermasculinity, and practices beyond intercourse. However, DL also emerged as a label of particular prominence when discussing what MSM means and how it influences sex and sexual identities. Participants described a tension between the sexual desirability of DLs and HIV infection and transmission associated with DL and trades in the broader society. Participants describe how DLs are portrayed as the infectors or carriers of HIV due to the secrecy of having unprotected sex with other men and also women, infecting their female partners with HIV. For example, participants described how the majority of Black women who have HIV and STIs were infected by DL same-gender-loving Black men:

“…85% of women get HIV/AIDS from men that are, have HIV, that [are] DL, trade guys...because openly, women are not supposedly going to sleep with a openly gay man.” [FG4]

This quote shows that the perception of secrecy is a central characteristic of DLs and places them at ‘fault’ for HIV transmission. However, viewing the experiences of DLs at the intersection of (Black) race, (masculine) gender, and (same sex attraction) sexuality within larger social structural forces (e.g., homophobia) indicates that both the perception of secrecy and HIV transmission attached to their DL identity feed into each other and serve to simultaneous eroticize and stigmatize DLs. Participants also highlighted that having sex with a DL is particularly erotic because in many cases risky/illicit sex is a secret and intimacy is heightened due to the sharing of an illicit event:

"DL is… very much something that a lot of people look for. Not because it's forbidden. It's kinda like that secrecy." [FG2]

The emphasis of secrecy, seen above as erotic, was also described as needing to be maintained. The pressure to maintain secrecy of who is DL can pose physical danger for those involved in the community. One participant discussed how a DL can act violently towards another same-gender-loving Black man who has knowledge of his same-sex sexual interest:

"Now DL is a guy who's down-low and he don't identify as gay but he still mess with men and if you tell somebody he'll shoot you in the face (laughter)." [FG1]

This juxtaposing between the erotic and the violent was further compounded by the laughter that was present during the conversation. Although the participant laughed following his comment of being shot in the face by a DL, it triggered a conversation among the focus group participants about DLs' engagement in interpersonal violence to maintain secrecy.

The duality of DL, embodying both negative and positive aspects, are reflected in the narratives of men speaking about DLs. This complexity highlights that secrecy occurs at multiple levels; within the community and in the context within which same-gender-loving Black men are nested. Jointly, perception of HIV transmission and secrecy both serve to maintain non-disclosure of same-sex sexual behaviors to sexual partners among DLs, increasing likelihood of DLs' engaging in unprotected intercourse and therefore risk for HIV infection.

Resistance narratives

Counter narratives against the prevailing gender stereotypes were described as influencing sexual roles and sexual identities. These counter narratives described the liminal periods and spaces when condom negotiations between more masculine-aligned labels versus feminine-aligned labels (e.g., tops and bottoms) shift in power, and where gendered sexual scripts are turned on their head. Power dynamics regarding condom use and safer sex practices can shift, dissolve, and/or be reconstructed. As noted by one participant, "strong" bottoms have the "self control" to refuse engaging in anal sex without a condom:

“If you are a strong bottom… when it comes to, 'Hey babe I don’t want to use a condom', then you know you have some bottoms that are like, 'Whoa, then we’re not having sex' and no matter how much they kiss on you and try to put hickies on your neck and all of that, you have to have that kind of self control to where you’re like, 'Well we’re not having sex without condoms'.” [FG2]

Similarly, other focus group participants echoed the notion that feminine stereotyped sexual practices, such as being bottom, can be powerful and dominate condom negotiation. One participant explained how some DL tops want to go "raw," with him but will "get their heads beaten" by someone like him, a dominant bottom [FG3].

Finally, focus group participants discussed fluidity of sexual identities and sexualities, as being mutable and contextual. Role switching was described as common, irrelevant as self-identification as a top or bottom, and can occur in the context of relationships. Participants described how they would change their motives for the man that they care for and love.

"I've seen tops become bottoms…Let's say I'm in a relationship. I'm a top, you're a bottom. But if we get in a relationship where we really care for each other, we love each other, we want to switch it. If you really love (him), you will do that for that person." [FG3]

Moreover, participants commonly described mobility within strata of the social and sexual desirability hierarchy within same-gender-loving Black male sub-labels as associated with economic fluctuations.

"But it does happen, like throughout a lifetime, maybe I'm a floor punk at 21, but I don't want to be a floor punk all my life…So I try to man up or maybe something else at 28 or 31, you know…They can get up and go get a job…" [FG2]

The shift from (younger) floor punk to (older) professional over the participant's life course reflected the intersection of age and class identities and movement through other social structures. The shift to occupying a higher position in the desirability hierarchy indicated agency, a reclaiming of subjectivity, and exploration of alternative possibilities.

Discussion

Our results suggest that the contemporary epistemological configurations of sexual identities, behaviors, and meanings impacting the lives and well-being of same-gender-loving Black men are not readily captured by the category 'MSM'. The diversity of labels and identities highlight a fundamental tension between the needs of the diverse same-gender-loving Black male community and the existing provision of HIV and AIDS-related interventions and services. Importantly, discussions around same-gender-loving Black male subgroups and HIV risk reflect how these individuals manage their racial, gendered, sexual, and class subjectivities. In this context, the use of labels and identities were a process, constantly being reconfigured across social contexts and stages in life, which included identification and dis-identification, and tensions between agency and social structure.

According to these narratives, the prominent social, political, and cultural factors that structured HIV vulnerability were gender, economic disparities, and substance use and abuse. These factors were reflected in descriptions of sub-labels within the term MSM and their ordering in a sexual and social desirability hierarchy. Privileged statuses, meaning those associated with positive attributes and/or power, included labels associated with masculine gender and higher socioeconomic class characteristics. Conversely, non-privileged statuses represented in sub-labels were associated with feminine gender, lower socioeconomic status, and perception of substance use or abuse. Men's intersectional positions were woven into narratives of how these identities can be lived, and how these intersecting identities influenced social and biomedical prevention efforts. For instance, the heterosexual male role (e.g., DL and trade) were described as avoiding HIV care and having limited engagement with HIV prevention strategies, as were those individuals who displayed more feminine characteristics (e.g., floor punk, punk, trans, sissies). Other labels that were perceived as most 'risky' or vulnerable to HIV infection and transmission were those that intersected with other social categories, such as low socioeconomic status (e.g., floor punk, street walker, porn star), and drug use (e.g., powder head and pill popper).

When discussing more masculine same-gender-loving Black male sub-labels, such as DLs and trades, participants noted the challenges with masculine/feminine identities and labels and their prescribed behaviors, the stigma attached to the DL identity and the pressure to maintain the Black heterosexual male role. These findings echo previous literature noting that the construction of the DL top as a reservoir of infection and as a bridge between the Black same-gender-loving male and heterosexual communities creates moral and cultural panic in both communities (McCune, 2014). Moreover the stigma of having same-sex relationships might be increased among masculine same-gender-loving Black men in the Deep South as these individuals are situated in communities that often stigmatize homosexuality, while, simultaneously expected to adhere to cultural norms which fuel notions of Black hypermasculinity and anti-feminine appearance and mannerisms (Fields et al, 2015). Participants described acting masculine as both a gender performance and a form of role flexing, paralleling other literature suggesting that these traits may be adaptive strategies to avoid suspicions from friends, family, and others in the heterosexual community (Butler, 1999; Balaji et al, 2012). Jointly, being subjected to the stigma attached to DL and gender role strain both serve to negatively affect HIV testing behaviors and condom use during anal intercourse. Emergent themes also highlighted the incongruence of masculine/feminine identities and expected sexual behaviors; for instance, a jock who may prefer to be a bottom. These findings indicate a need for HIV prevention strategies that seek to actively dispel gender stereotypes and expectations by promoting an awareness of multiple sexual identities, eroticism, and pleasure as factors influencing sexual behaviors.

Focus group discussions described the DL paradox as the simultaneous stigmatization of DLs from society and the Black community, and eroticization of the secrecy of DL sexual behavior within the same-gender-loving Black community. McCune (2014) discussed the DL paradox around a common descriptor pervasive within the media, "the Down-Low Brotha," whereby DLs are blamed by society and the Black community for Black women's increase in HIV infection rates, which create a moral panic around the Black family. However, McCune’s work disregards psychological processes at play within the same-gender-loving Black community. Understandings of this paradox can best be captured through an intersectional lens that involve both social structural forces (e.g., homophobia and hypermasculinity) and internalized pathways (eroticization of DL). The application of an intersectional analysis exposed the nuance of multiple identities, labels, and subjectivities and the interactions with social structural forces at the community and societal level that influence behaviors and understandings of self.

Echoing Mocombe's (2008) notion of practical consciousness, focus group participants described how feminine bottoms and floor punks chose alternative practices and life choices upon reflecting on behaviors prescribed to their non-privileged identities, thereby showing the ways in which same-gender-loving Black men resist stereotypes. These examples of resistance underscores that terms cannot be presumed or taken for granted since such identities and labels (and the meanings associated with them) are the product of the field of power where the boundaries are constantly being contested. Furthermore, the fluidity of identities and their subjective meanings in the focus groups' narrative accounts suggest that these identities are constantly being re-configured over time and across social contexts (Wetherell, 2008). As an example of these nuanced identity terms, in some of the focus group narratives, feminine bottoms emerged as an identity that can assert power over condom negotiation when engaging in anal intercourse with masculine tops, and role switching can occur in intimate relationships and across time with varying partners. Here, shared narratives of agency in the face of stereotypes regarding HIV infection in their community revealed that negotiations over safer sex are contextual and situational (Weis and Fine, 2004; He and Ross, 2012). Participants also discussed how same-gender-loving Black men in the lower strata of the social and sexual hierarchy (e.g., floor punks) can shift toward becoming members of the higher strata (e.g., professionals) over their life course. This suggests that HIV prevention interventions need to not only adapt to diversity and overlap in identities and labels, but also to ongoing processes of change.

These findings are particularly relevant for informing the implementation and acceptability of HIV prevention strategies among same-gender-loving Black men. Despite advances in biomedical technology, behavioral and community-based approaches continue to be a crucial component to HIV prevention acceptability and sustainability (Aggleton and Parker, 2015). As evidenced in this study, the diverse sexual identities within 'MSM' among same-gender-loving Black men in the Deep South and their associated meanings in relation to HIV and AIDS are locally and culturally distinct from other MSM communities within the United States and worldwide (Meyer et al, 2010). Importantly, understanding how same-gender-loving Black men in the Deep South experience these unique local identities at the intersection of race, class, gender, and sexuality in relation to social structural forces (stigma, discrimination, poverty, low education) is crucial to understanding differential HIV patterning and effective ways to ameliorate the burden of HIV among those most impacted.

There are important limitations to consider when interpreting the impacts of this study. Nuanced identity terms, such as local identities that reflect the diverse practices, sexualities, and subjectivities in these men's everyday lived experiences cannot be captured within labels. Furthermore, the terms, definitions, and/or labels presented here are not static and are amenable to change. The space where the focus groups sessions were held, a clinic that focused on providing health services to the LGBT community, may have influenced the narratives and discussions evoked during the focus groups. In efforts to minimize the potential for social desirability bias, all focus group discussions were held after hours and no clinic staff were present when participants arrived or at any point during study procedures. Despite this potential bias, the clinic provided a comfortable and non-threatening space that was conducive to productive discussions on sensitive topics. We did not explore environment and place as a potential factor to capture HIV risk levels among MSM identities in various situations. For scholars interested in this research, pile sorting and ethnography may be valuable methods to explore how sexual identities within 'MSM' interact with public/private locations where sex occur (e.g., clubs, cars, parks, rest stops, public restrooms, prisons, homes) to produce differential HIV sexual risk behaviors. As an exploratory qualitative study, the results from this study pertained only to those individuals directly engaged in our study and their reflections of the communities within which they live which is Jackson, Mississippi.

Nonetheless, this study furthers existing public health literature by highlighting and describing the diverse range of sexual identities and subjectivities within 'MSM' in a same-gender-loving Black male community located in a region of the United States disproportionately burdened by HIV and AIDS. The use of intersectionality theory to frame how the experiences of same-gender-loving Black men intersect with race, gender, and class to pattern differences between sexual identities within 'MSM' to produce differential HIV vulnerability may be key to future HIV and AIDS research, services and interventions targeting same-gender-loving Black men in the Deep South. These results seek to focus attention on the need to further investigate the multiple identities, labels, and subjectivities circulating within and around the term MSM among Black men to make visible the factors that directly and indirectly fuel HIV vulnerability.

Acknowledgments

The authors give thanks to all study participants for their time and effort. We thank Dr. Leandro Mena for the informal conversations that helped the initial development of the study. We also thank Nikendrick Sturdevant, Gerald Gibson and Reginald Stevenson for the recruitment of focus group participants. Finally, we would like to acknowledge Dr. Simon Obendorf for his theoretical insights on power relations between gender and sexuality in same-gender-loving populations.

References

- Aggleton P, Parker R. Moving beyond biomedicalization in the HIV response: Implications for community involvement and community leadership among men who have sex with men and transgender people. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105(8):1152–1558. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen L. Managing masculinity: Young men’s identity work in focus groups. Qualitative Research. 2005;5(1):35–57. [Google Scholar]

- Balaji AB, Oster AM, Viall AH, Heffelfinger JD, Mena LA, Toledo CA. Role flexing: How community, religion, and family shape the experiences of young Black men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2012;26:730–737. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boellstorff T. But do not identify as gay: A proleptic genealogy of the MSM category. Cultural Anthropology. 2011;26:287–312. [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. When Black + Lesbian + Woman ≠ Black Lesbian Woman: The methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex Roles. 2008;59:312–325. [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality-- an important theoretical framework for public health. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:1267–1273. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler J. Bodily inscriptions, performative subversions. In: Price JJ, Shildrick M, editors. Feminist theory and the body: A reader. New York, NY: Routledge; 1999. pp. 416–422. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV infection among young black men who have sex with men--Jackson, Mississippi, 2006–2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2009;58:77–81. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5804a2.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence among adults and adolescents in the United States, 2007–2010. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report, 2012. 2012;17(4):1–26. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_hssr_vol_17_no_4.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH. Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. New York, NY: Routledge; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. In: Crenshaw K, Gotanda N, Peller G, Thomas K, editors. Critical race theory: The key writings that formed the movement. New York, NY: The New Press; 1995. pp. 357–383. [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin SL. Who is epidemiologically fathomable in the HIV/AIDS epidemic? Gender, sexuality, and intersectionality in public health. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2005;7:615–623. doi: 10.1080/13691050500100385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields EL, Bogart LM, Smith KC, Malebranche DJ, Ellen J, Schuster MA. "I always felt I had to prove my manhood": Homosexuality, masculinity, gender role strain, and HIV risk among young black men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105:122–131. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He MF, Ross S. Narrative of curriculum in the South: Lives in-between contested race, gender, class, and power. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing (Online) 2012;28(3):1–9. Retrieved from http://journal.jctonline.org/index.php/jct/article/download/378/pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Hickson DA, Truong N, Smith-Bankhead N, Sturdevant N, Stanton J, Gipson J, Mena L. Socio-ecological study of sexual behaviors and HIV/STI among African American men who have sex with men in the Southeastern United States (U.S.): Rationale, design and methods. PLOS ONE. 2015 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143823. (accepted) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussen SA, Stephenson R, del Rio C, Wilton L, Wallace J, Wheeler D. HIV testing patterns among Black men who have sex with men: A qualitative typology. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):1–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCune JQ., Jr . Sexual discretion: Black masculinity and the politics of passing. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer W, Costenbader EC, Zule WA, Otiashvili D, Kirtadze I. ‘We are ordinary men’: MSM identity categories in Tbilisi, Georgia. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2010;12:955–971. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2010.516370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett GA, Flores SA, Peterson JL, Bakeman R. Explaining disparities in HIV infection among black and white men who have sex with men: A meta-analysis of HIV risk behaviors. AIDS. 2007;21:2083–2091. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282e9a64b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett GA, Peterson JL, Flores SA, Flores SA, Hart TA, Jeffries WL, 4th, Remis RS. Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: A meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2012;380:341–348. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60899-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mississippi State Department of Health. State of Mississippi 2010 STD/HIV epidemiologic profile. 2010 Retrieved from http://msdh.ms.gov/msdhsite/_static/resources/3591.pdf.

- Mocombe PC. The soul-less souls of Black folk: A sociological reconsideration of Black consciousness as Du Boisian double consciousness. Lanham, MD: University Press of America; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nunn A, Yolken A, Cutler B, Trooskin S, Wilson P, Little S, Mayer K. Geography should not be destiny: Focusing HIV/AIDS implementation research and programs on microepidemics in US neighborhoods. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104:775–780. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oster AM, Pieniazek D, Zhang X, Switzer WM, Ziebell RA, Mena LA, Heffelfinger JD. Demographic but not geographic insularity in HIV transmission among young black MSM. AIDS. 2011;2:2157–2165. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834bfde9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks CW. African-American same-gender-loving youths and families in urban schools. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services. 2001;13:41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Petchesky RP. The language of “sexual minorities” and the politics of identity: a position paper. Reproductive Health Matters. 2009;17:105–110. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(09)33431-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson AR, Vidal-Ortiz S. Displacing the dominant "down low" discourse: Deviance, same-sex desire, and Craigslist.org. Deviant Behavior. 2013;34(3):224–241. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart DW, Shamdasani PN, Rook DW. Focus groups: Theory and practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ward J. Dude-sex: White masculinities and 'authentic' heterosexuality among dudes who have sex with dudes. Sexualities. 2008;11:414–434. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins-Hayes C. Intersectionality and the sociology of HIV/AIDS: past, present, and future research directions. Annual Review of Sociology. 2014;40:431–457. [Google Scholar]

- Weber L. Understanding race, class, gender, and sexuality: A conceptual framework. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Weis L, Fine M. Working method: Research and social justice. New York, NY: Routledge; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RS. Learning from strangers: The art and method of qualitative interview studies. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wetherell M. Subjectivity or psycho-discursive practices? Investigating complex intersectional identities. Subjectivity. 2008;22:73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Young R, Meyer IH. The trouble with "MSM" and "WSW": Erasure of the sexual-minority person in public health discourse. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:1144–1149. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.046714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]