Abstract

Objective

Given the lack of clarity on the expression status of SRC1 protein in breast cancer, we attempted to ascertain the clinical implications of the expression of this protein in breast cancer.

Methods

Samples from 312 breast cancer patients who were followed up for 5 years were analyzed in this study. The associations of SRC1 expression and clinicopathological factors with the prognosis of breast cancer were determined.

Results

The 312 breast cancer patients underwent radical resection, and 155 (49.68%) of them demonstrated high expression of SRC1 protein. No significant differences were found for tumor size, estrogen receptor expression, or progesterone receptor expression (P=0.191, 0.888, or 0.163, respectively). It is noteworthy that SRC1 expression was found to be related to HER-2 and Ki-67 expression (P=0.044 and P=0.001, respectively). According to logistic regression analysis, SRC1 expression was also significantly correlated with Ki-67 and HER-2 expression (P=0.032 and P=0.001, respectively). Survival analysis showed that patients with a high expression of SRC1 and NANOG and those with SRC1 and NANOG coexpression had significantly poorer postoperative disease-specific survival than those with no expression in the HER-2-positive group (P=0.032, 0.01, and P=0.01, respectively).

Conclusion

High SRC1 protein expression was related to the prognosis of HER-2-overexpressing breast cancers.

Keywords: breast cancer, prognosis, molecular classification, SRC1, NANOG

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most frequently diagnosed cancers and the leading cause of cancer-related death in women worldwide.1,2 Although some pathological factors, including estrogen receptors (ERs), progesterone receptors (PRs), HER-2, and Ki-67, are used as references in diagnosis and treatment, the recurrence and metastasis of breast cancer remain the biggest obstacles affecting the survival of patients with breast cancer.3,4 Therefore, screening biomarkers and potential targets continues to be of great significance in the management of breast cancer.

At present, the mechanisms underlying recurrence and metastasis in relation to SRC1 in breast cancer are not clearly understood.5,6 Furthermore, the correlation of SRC1 and NANOG in human breast cancer and the relevance of their coexpression with respect to clinical parameters remain to be elucidated. The SRC family includes SRC1, SRC2, and SRC3. These SRC transcriptional coactivators robustly enhance gene expression by interacting with nuclear hormone receptors such as ERs, PRs, and glucocorticoid receptors, as well as other transcription factors.7 Normal viability, somatic growth, and reproductive function have been found to be exhibited in SRC1 knockout mice and to display a delay in mammary gland growth and Purkinje cell differentiation.8 NANOG is a transcription factor that plays a key role in maintaining the self-renewal capacity and pluripotency of embryonic stem cells, and it is a biomarker of cancer stem cells.9–11 Previous studies have shown that NANOG regulates cancer progression and that its expression levels are associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer patients.12,13 Some studies have also found that SRC1 plays an important role in the proliferation, invasion, and metastasis of some types of cancer cells via certain pathways.5–7 A study in mice showed that SRC1 and NANOG expression contributed to the modulation of the transcriptional activity of the core transcription factors of the pluripotent network and could be implicated in cell fate decisions upon the onset of differentiation in embryonic stem cells.14

In this study, we characterized the levels of SRC1 and NANOG expression in samples from 312 breast cancer patients and analyzed their association with the clinicopathological characteristics and prognoses of these patients.

Materials and methods

Clinical samples

A total of 312 breast cancer samples were obtained from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Jilin University and Liaoning Cancer Hospital and Institute between January 2005 and December 2008. The patients had been diagnosed by histological examination of surgical tissue samples and had undergone radical surgical resection. The inclusion criteria for the study were 1) patients undergoing curative surgery, 2) pathological examination of the resected tumor specimens, 3) pathological examination of >15 lymph nodes after the surgery, and 4) the availability of a complete medical record. The demographic and clinical data of individual patients were obtained from medical records.15 Individuals with breast cancer but not fulfilling the inclusion criteria were excluded. Written informed consent was obtained from all of the patients, and this study and the experimental protocol were approved by the ethics committee of Jilin University.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Individual breast cancer tissue samples were fixed in 10% formaldehyde solution (pH 7.0) and embedded in paraffin. The paraffin-embedded tissue sections (4 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and examined by light microscopy by pathologists blinded to patient details. SRC1 and NANOG expression levels were characterized by immunohistochemistry. Briefly, the paraffin-embedded breast tumor tissue sections were dewaxed, rehydrated, and treated with 3% H2O2 in methanol, followed by overnight incubation with primary antibodies against SRC1 and NANOG (Abcam, Boston, MA, USA). Subsequently, the sections were incubated with biotinylated Multilink swine anti-goat/mouse/rabbit IgG (Dako Denmark A/S, Glostrup, Denmark). The sections were washed, and the bound antibodies were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated avidin–biotin complex (1:1,000 dilution; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and visualized using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine. The sections were then counterstained with Gill’s hematoxylin.16

The intensity of anti-SRC1 and anti-NANOG staining was semiquantitatively analyzed. Individual cells with yellow-to-brown staining in the nucleus and/or cytoplasm of the cells were considered positive cells. SRC1 and NANOG expression levels were scored semiquantitatively according to the following criteria: −, <1% of neoplastic cells expressing SRC1 and NANOG; +, ≥1% of morphologically unequivocal neoplastic cells expressing SRC1 and NANOG.16

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. The difference among groups was determined by χ2 and Fisher’s least significant difference using SPSS software, Version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

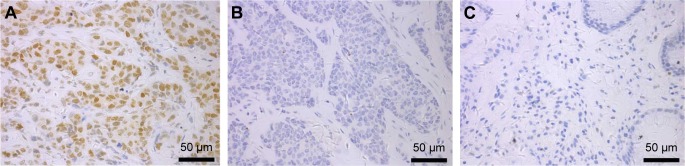

Expression status of SRC1 and NANOG in breast cancer specimens

The protein expression levels of SRC1 and NANOG were examined by immunohistochemical staining. We found 155 (49.68%) of 312 samples to have high SRC1 expression and 91 (29.17%) to have high NANOG expression (Table 1 and Figure 1). After univariate analysis, SRC1 was observed to be significantly correlated with HER-2 and Ki-67 expression (P=0.044 and 0.001), while age, tumor size, and ER and PR expression were not (P=0.651, 0.191, 0.888, and 0.163, respectively). It is noteworthy that SRC1 was found to be related to lymph node metastasis (P=0.005), which was in accordance with the survival analysis described later in the text.

Table 1.

Relationship between clinicopathological variables and SRC1 or NANOG expression

| Variables | Total patients (n) | SRC1

|

NANOG

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| − (n) | + (n) | P-value | − (n) | + (n) | P-value | ||

| Age (years) | 0.651 | 0.709 | |||||

| <50 | 169 | 83 | 86 | 118 | 51 | ||

| ≥50 | 143 | 74 | 69 | 103 | 40 | ||

| Tumor size | 0.191 | 0.001 | |||||

| T1 | 145 | 60 | 85 | 137 | 28 | ||

| T2 | 155 | 89 | 66 | 99 | 56 | ||

| T3 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 7 | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.005 | 0.001 | |||||

| N0 | 111 | 67 | 44 | 102 | 9 | ||

| N1 | 87 | 47 | 40 | 66 | 21 | ||

| N2 | 80 | 32 | 48 | 42 | 38 | ||

| N3 | 34 | 11 | 23 | 11 | 23 | ||

| ER | 0.888 | 0.440 | |||||

| − | 63 | 31 | 32 | 42 | 21 | ||

| + | 249 | 126 | 123 | 179 | 70 | ||

| PR | 0.163 | 0.321 | |||||

| − | 49 | 20 | 29 | 28 | 21 | ||

| + | 203 | 137 | 126 | 133 | 70 | ||

| HER-2 | 0.044 | 0.002 | |||||

| − | 271 | 130 | 141 | 201 | 70 | ||

| + | 41 | 27 | 14 | 20 | 21 | ||

| Ki-67 | 0.001 | 0.002 | |||||

| − | 62 | 48 | 14 | 54 | 8 | ||

| + | 250 | 109 | 141 | 167 | 82 | ||

Abbreviations: −, negative; +, positive; ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor.

Figure 1.

SRC1 expression in breast cancer was characterized by immunohistochemistry.

Notes: (A) Positive anti-SRC1 staining in the lymph node-positive cases (magnification ×400). (B) Negative anti-SRC1 staining in the lymph node-negative tumors (magnification ×400). (C) Negative anti-SRC1 staining in the paracancerous tissues (magnification ×400).

We also tested the expression status of the cancer stem cell-related factor NANOG in the same 312 cases. NANOG was significantly related to tumor size and lymph node metastasis (P=0.001 and 0.001, respectively), while age and ER and PR expression were not (P=0.709, 0.440, and 0.321, respectively). Interestingly, NANOG was also found to be related to HER-2 and Ki-67 expression (P=0.002 and 0.002, respectively) (Table 1).

Screening for SRC1-related factors in breast cancer specimens

We performed logistic regression analysis to select the factors related to SRC1 expression. HER-2, Ki-67, and lymph node metastasis were found to be correlated with SRC1 expression (P=0.001, 0.032, and 0.001, respectively) (Table 2). NANOG was also found to be correlated with SRC1 expression; however, the underlying mechanism was not clear.

Table 2.

Logistic regression analysis of the factors related to SRC1 expression in breast cancer

| Characteristic | OR | 95% CI for OR | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.936 | 0.582–1.438 | 0.853 |

| Tumor size | 1.351 | 0.791–1.926 | 0.625 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 2.052 | 1.571–3.402 | 0.001 |

| Ki-67 | 1.833 | 1.247–2.948 | 0.032 |

| ER | 1.215 | 0.649–1.704 | 0.371 |

| PR | 0.927 | 0.483–1.816 | 0.256 |

| HER-2 | 2.167 | 1.742–3.604 | 0.001 |

| NANOG | 1.997 | 1.353–3.628 | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor.

Survival analysis

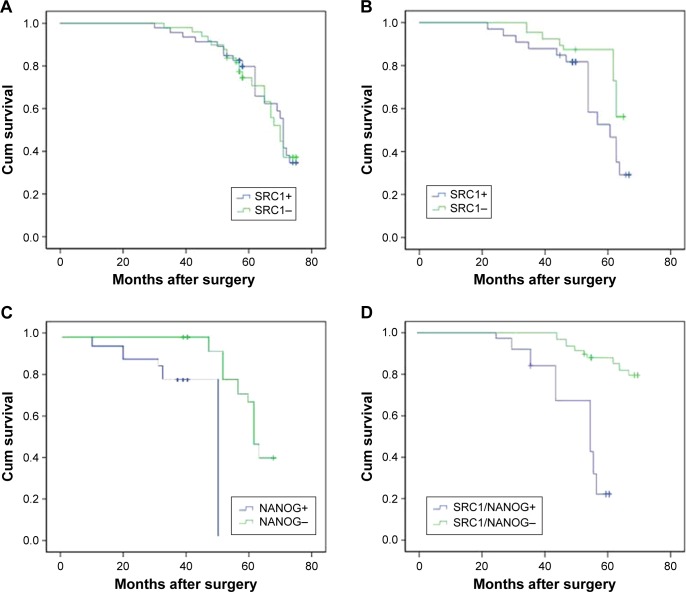

There was no difference with regard to local and distant metastases between patients with or without SRC1 protein expression (30.97% vs 28.67%). However, local and distant metastases were significantly higher in patients expressing SRC1 compared with SRC1-negative patients in the HER-2-positive group (42.86% vs 25.93%). Moreover, the coexpression of SRC1 and NANOG predicted a higher recurrence rate compared to the other HER-2-positive patients (25.00% vs 60.00%).

Survival analysis showed that the patients with a high expression of SRC1, as well as those with SRC1 and NANOG coexpression, had significantly poorer postoperative disease-specific survival than those with no expression in the HER-2-positive group (P=0.032 and 0.01) (Figure 2). According to Cox regression, the following were identified as prognostic factors (Table 3): tumor number (P=0.010); lymph node metastasis (P=0.001); expression of Ki-67 (P=0.024), ER (P=0.036), HER-2 (P=0.010), SRC1 (P=0.001), and NANOG (P=0.001); and coexpression of SRC1 and NANOG (P=0.001).

Figure 2.

Survival analysis of SRC1 and NANOG expression in breast cancer.

Notes: Kaplan–Meier curves of overall survival showed that there was no prognosis difference in the SRC1-positive or -negative groups in all enrolled cases (P=0.450; A). Survival analysis showed that the patients with a high expression of SRC1 and NANOG, as well as those with SRC1 and NANOG coexpression, had significantly poorer postoperative disease-specific survival than those with no expression in the HER-2-positive group (P=0.032, P=0.01, and P=0.01, respectively; B–D).

Table 3.

Cox regression analysis in predicting the overall survival of breast cancer patients

| Variables | Univariate analysis

|

Multivariate analysis

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P-value | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Age | 0.945 | 0.773–1.425 | 0.372 | 0.918 | 0.618–1.501 | 0.451 |

| Tumor size | 1.671 | 1.332–1.946 | 0.010 | 1.628 | 1.427–2.154 | 0.010 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 2.773 | 1.684–3.943 | 0.001 | 2.462 | 1.580–3.736 | 0.001 |

| Ki-67 | 1.592 | 1.146–2.034 | 0.020 | 1.539 | 1.147–2.045 | 0.024 |

| ER | 0.763 | 0.522–0.951 | 0.045 | 0.710 | 0.437–0.901 | 0.036 |

| PR | 0.914 | 0.643–1.437 | 0.083 | 0.942 | 0.705–1.535 | 0.142 |

| HER-2 | 1.971 | 1.467–3.118 | 0.001 | 1.840 | 1.325–3.028 | 0.001 |

| SRC1 | 1.573 | 1.294–2.327 | 0.035 | 1.630 | 1.328–2.742 | 0.010 |

| NANOG | 2.274 | 1.689–3.771 | 0.001 | 2.113 | 1.626–3.810 | 0.001 |

| SRC1+/NANOG+ | 3.035 | 2.112–4.642 | 0.001 | 3.104 | 2.432–4.381 | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: ER, estrogen receptor; CI, confidence interval; PR, progesterone receptor.

Discussion

In a recent study, Redmond et al17 investigated the role of p160 coactivators (the SRC gene family) and their interactions with ERs in the development of resistance to endocrine treatment. They showed SRC1 to be a strong independent predictor of reduced disease-free survival, whereas the interactions of the p160 proteins with ERα could predict the response of patients to endocrine treatment. In another study, both SRC1 and Twist1 were reported to be associated with tumor invasion, metastasis, and poor prognosis in breast cancer.5,6 Xu et al18 found that SRC1 upregulates Twist1 expression and promotes breast cancer cell migration and invasion. In our study, SRC1 was not found to be related to the tumor size but the lymph node metastasis. Wang et al7 also reported that SRC1 specifically promotes metastasis without affecting primary tumor growth through mediating Ets-2-mediated HER-2 expression and activating CSF-1 expression for macrophage recruitment.

NANOG expression has been suggested to be a valuable biomarker to predict the outcome of patients with breast cancer. NANOG expression levels are also associated with the poor prognosis of colorectal cancer patients and enhanced lung cancer malignancy.19,20 However, there is no information on the association of SRC1 and NANOG expression with the survival of breast cancer patients. Furthermore, the role of SRC1 regulation in NANOG expression and the relevance of their coexpression in clinicopathological features in human breast cancer have not been described thus far.

Herein, we studied the expression status of SRC1 and NANOG, as well as their coexpression in breast cancer. Previous studies have demonstrated that SRC1 and NANOG significantly increase in 34% and 37.30% of breast tumors, respectively. In this study, we found that 49.68% cases were SRC1 positive and 29.17% cases were NANOG positive. According to the univariate analysis, SRC1 was significantly correlated with HER-2 and Ki-67 expression. Xu et al18 also found SRC1 to be related to HER-2 expression, but they did not test the correlation between SRC1 and Ki-67, which indicated that SRC1 was related not only to the HER-2 expression status but also to the proliferation of breast cancer cells. However, we have not found a proper interpretation for the observation that SRC1 was related to Ki-67 expression but did not increase the primary cancer growth. Double staining of SRC1 and NANOG in breast cancer cell lines should be done and the potential mechanism of them regulating the metastasis of breast cancer should be found out in the future study. The former study reported that SRC1 knockdown inhibited Ets-2-mediated HER-2 expression and Akt activation in the mammary tumors.7

Interestingly, NANOG was also significantly related to HER-2 and Ki-67 expression in this study, and NANOG was found to be correlated with SRC1 expression. In the survival analysis, SRC1 protein expression, and in particular, the coexpression of SRC1 and NANOG, was found to be a likely prognosis predictor for HER-2-positive patients.

There were some limitations in the study. The expression status of SRC1 and NANOG was analyzed only by immunohistochemistry, although it would have been better to perform other methods (quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction or expression arrays) to test the expression of the factors at different levels.

Conclusion

In summary, our data indicated that the relative levels of SRC1 expression were inversely associated with the proliferation and aggressiveness of HER-2-overexpressing breast cancers. There might be a correlation between SRC1 and NANOG in regulating the proliferation and migration of breast cancer cells. Our data provide new insights into the regulation of the proliferation and migration of breast cancer cells. These novel findings might aid in the design of new therapeutic strategies for breast cancer intervention.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the grant from the China National Natural Science Foundation (No 812272472).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Weigelt B, Mackay A, A’Hern R, et al. Breast cancer molecular profiling with single sample predictors: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(4):339–349. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gelmon K, Dent R, Mackey JR, Laing K, McLeod D, Verma S. Targeting triple-negative breast cancer: optimising therapeutic outcomes. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(9):2223–2234. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reeder-Hayes KE, Carey LA, Sikov WM. Clinical trials in triple negative breast cancer. Breast Dis. 2010;32(1–2):123–136. doi: 10.3233/BD-2010-0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaspers JE, Rottenberg S, Jonkers J. Therapeutic options for triple-negative breast cancers with defective homologous recombination. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1796(2):266–280. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu J, Wu RC, O’Malley BW. Normal and cancer-related functions of the p160 steroid receptor co-activator (SRC) family. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(9):615–630. doi: 10.1038/nrc2695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu J, Qiu Y, DeMayo FJ, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O’Malley BW. Partial hormone resistance in mice with disruption of the steroid receptor coactivator-1 (SRC-1) gene. Science. 1998;279(5358):1922–1925. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5358.1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang S, Yuan Y, Liao L, et al. Disruption of the SRC-1 gene in mice suppresses breast cancer metastasis without affecting primary tumor formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(1):151–156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808703105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishihara E, Yoshida-Komiya H, Chan CS, et al. SRC-1 null mice exhibit moderate motor dysfunction and delayed development of cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Neurosci. 2003;23(1):213–222. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-01-00213.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qin L, Liu Z, Chen H, Xu J. The steroid receptor coactivator-1 regulates twist expression and promotes breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 2009;69(9):3819–3827. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Apostolou P, Toloudi M, Papasotiriou I. Identification of genes involved in breast cancer and breast cancer stem cells. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press) 2015;7:183–191. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S85202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li N, Deng W, Ma J, et al. Prognostic evaluation of NANOG, Oct4, Sox2, PCNA, Ki67 and E-cadherin expression in gastric cancer. Med Oncol. 2015;32(1):433. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0433-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang D, Lu P, Zhang H, et al. Oct-4 and NANOG promote the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of breast cancer stem cells and are associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2014;5(21):10803–10815. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu C, Xu L, Liang S, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Zhang F. Lentivirus-mediated shRNA targeting Nanog inhibits cell proliferation and attenuates cancer stem cell activities in breast cancer. J Drug Target. 2016;24(5):422–432. doi: 10.3109/1061186X.2015.1082567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hogan MS, Parfitt DE, Zepeda-Mendoza CJ, Shen MM, Spector DL. Transient pairing of homologous Oct4 alleles accompanies the onset of embryonic stem cell differentiation. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16(3):275–288. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu D, Xu H, Ren Y, et al. Cancer stem cell-related gene periostin: a novel prognostic marker for breast cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e46670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu C, Chen B, Zhu J, et al. Clinical implications for nestin protein expression in breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 2010;101(3):815–819. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01422.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Redmond AM, Bane FT, Stafford AT, et al. Coassociation of estrogen receptor and p160 proteins predicts resistance to endocrine treatment; SRC-1 is an independent predictor of breast cancer recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(6):2098–2106. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu Y, Hu B, Qin L, et al. SRC-1 and Twist1 expression positively correlates with a poor prognosis in human breast cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2014;10(4):396–403. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.8193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mattoo AR, Zhang J, Espinoza LA, Jessup JM. Inhibition of NANOG/NANOGP8 downregulates MCL-1 in colorectal cancer cells and enhances the therapeutic efficacy of BH3 mimetics. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(21):5446–5455. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du Y, Ma C, Wang Z, Liu Z, Liu H, Wang T. NANOG, a novel prognostic marker for lung cancer. Surg Oncol. 2013;22(4):224–229. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]