Abstract

Rationale: The World Trade Center (WTC) collapse generated caustic airborne particulates that caused chronic rhinosinusitis in exposed Fire Department of New York firefighters. Surgery was performed when symptoms remained uncontrolled despite medical management.

Objectives: To identify predictors of surgical intervention for chronic rhinosinusitis in firefighters exposed to airborne irritants at the WTC collapse site.

Methods: We assessed in 8,227 firefighters with WTC exposure between September 11, 2001 (9/11), and September 25, 2001, including WTC-site arrival time, months of rescue and recovery work, and eosinophil concentration measured between 9/11 and March 10, 2003. We assessed the association of serum cytokines and immunoglobulins with eosinophil concentration and surgery for rhinosinusitis in 112 surgical cases and 376 control subjects with serum available from the first 6 months after exposure to the WTC collapse site.

Measurements and Main Results: Between 9/11 and March 10, 2015, the surgery rate was 0.47 cases per 100 person-years. In the first 18 months post-9/11, surgical patients had higher mean blood eosinophil levels than study cohort patients (219 ± 155 vs. 191 ± 134; P < 0.0001). Increased surgery risk was associated with increasing blood eosinophil counts (hazard ratio [HR], 1.12 per 100 cells/μl; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.07–1.17; P < 0.001); arriving at the WTC site on 9/11 or September 12, 2001 (HR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.04–1.99; P = 0.03); and working 6 months or longer at the WTC site (HR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.14–1.93; P < 0.01). Median blood eosinophil levels for surgical patients were above levels for the cohort in all 18-month intervals March 11, 2000, through March 10, 2015, using 51,163 measurements representing 97,733 person-years of observation. Increasing age, increasing IL-17A, and low IgA in serum from 2001 to 2002 predicted blood eosinophil concentration in surgical patients but not in control subjects (R2 = 0.26, P < 0.0001; vs. R2 = 0.008, P = 0.56).

Conclusions: Increasing blood eosinophil concentration predicts surgical intervention for chronic rhinosinusitis, particularly in those with intense acute and prolonged exposure to airborne irritants. WTC-exposed Fire Department of New York firefighters who underwent irritant-associated sinus surgery are immunologically different from the cohort. Surgical patients have a higher blood eosinophil levels that is associated with mediators of mucosal immunity.

Keywords: sinusitis, otolaryngology surgery, eosinophils, particulate matter, cohort studies

Rhinosinusitis is a syndrome producing obstruction to nasal airflow, drip, anosmia, and facial pain. Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is defined as this constellation of symptoms lasting 3 or more months. The prevalence of CRS is between 13% and 17%, with 600,000 sinus surgeries performed in the United States during 2006 (1–3). In an analysis of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision–coded electronic medical records (EMRs) from a large private health system, researchers estimated a CRS incidence of 1.1 cases per 100 person-years (4).

The current European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps, published in 2012, recommended that sinus inflammation should be objectively confirmed by computed tomography (CT) and/or endoscopy and argued for separation of it into two distinct entities: CRS without nasal polyps and CRS with nasal polyps (5). In spite of high disease burden and associated morbidity, few longitudinal studies have provided data on risk factors for CRS, limiting approaches to model disease outcomes and institute effective prevention (4, 6–8).

Environmental particulate matter exposure is a risk factor for upper and lower airway disease (9, 10). The collapse of the World Trade Center (WTC) on September 11, 2001 (9/11), produced a dust cloud containing alkaline pulverized concrete and other building materials that irritated mucosal surfaces of the aerodigestive system. All individuals present at the WTC site before September 13, 2001, sustained intense particulate exposure, which produced upper airway symptoms, including nasal congestion and drip, in most survivors (11).

Rainfall 3 days after 9/11 reduced dust levels and may have played a role in lower levels of persistent aerodigestive symptoms in later-arriving Fire Department of New York (FDNY) firefighters (12). Digging activities to recover human remains continued through July 2002, producing chronic particulate reexposures. Upper airway filtration of larger particles protects the lower airway but can produce inflammation of the nose and paranasal sinuses, leading to CRS, which has, over time, become a major health concern in WTC-exposed populations (13–16). We have previously shown that chronic particulate exposure, defined by months of firefighter work at the WTC site, predicted health care use, including sinus surgery (12).

CRS has multiple inflammatory endotypes (17). Innate as well as Th2- and Th17-driven eosinophilic responses are observed in specimens from surgically treated patients with CRS (18–21), suggesting that separate eosinophilic inflammatory pathways produce CRS. IL-17A is an inflammatory mediator of sinus disease. Eosinophilia is present in WTC-exposed area residents and children with upper and lower respiratory complaints (14, 22).

In a small cross-sectional study, high blood eosinophil concentration soon after WTC exposure increased the odds of visualizing sinus polyps on CT scans, a risk factor for sinus surgery (23). This preliminary study led to the hypothesis that blood eosinophil concentration early after 9/11 may predict subsequent sinus surgery, a clearly defined disease with high morbidity and health care use (12). We therefore tested if increased blood eosinophil levels and associated inflammatory mediators, combined with WTC exposure, are risk factors for surgical-CRS in FDNY firefighters.

Methods

Study Population

This study included male firefighters who were employed by the FDNY on 9/11; first arrived at the WTC site between 9/11 and September 24, 2001; had an available eosinophil concentration from an FDNY medical monitoring examination between 9/11 and March 10, 2003; and consented to be research subjects. The Montefiore Medical Center and New York University institutional review boards approved this study.

Identification and Characterization of Patients with Chronic Rhinosinusitis

We obtained surgical-CRS occurrence data and dates from multiple sources, including the FDNY-WTC Health Program (FDNY-WTCHP) EMR, FDNY-WTCHP claims data, and the records of a WTC center of excellence otolaryngologist (M.R.S.). When the FDNY-EMR was the only identifier of surgical-CRS, a WTC treatment physician (M.D.W.) reviewed the FDNY-EMR notes to confirm the date and indication for surgical-CRS.

Otolaryngologists caring for patients with CRS were not provided patients’ WTC exposure specifics, job tasks, or FDNY-WTCHP eosinophil concentrations. CT reports were reviewed by a WTC treatment physician (D.J.P.), noting the symptoms as well as the presence of upper airway polyps or inflammation. CRS was defined by having sinus symptoms and sinus surgery or sinus CT and findings of inflammation or polyps.

Eosinophil, Exposure, and Demographic Data

Eosinophil concentrations were obtained from cell blood counts (CBCs) drawn at each WTCHP monitoring examination, scheduled at 12- to 18-month intervals, and sent to a single commercial laboratory. The first eosinophil concentration during each 18-month interval was used in the analysis. We did not use eosinophil measurements from physician encounters for symptom evaluation or treatment. Information documented during FDNY-WTCHP examinations included responses from self-administered questionnaires with questions about smoking, self-reported race and/or ethnicity, WTC arrival time, and months of work.

A never smoker was defined as consistently denying smoking on longitudinal questionnaires. High-intensity acute exposure was defined as arrival between the morning of 9/11 and the end of September 12, 2001; lower-intensity acute exposure was defined as arrival on or after September 13, 2001. High-intensity chronic exposure was defined as 6 or more months of rescue and/or recovery work, intermediate intensity was defined as 2–5 months, and lower intensity was defined as 1 month.

Serum Biomarker Cases and Control Subjects

Serum was obtained from the same venipuncture as blood drawn at the first post-9/11 medical monitoring examination and was stored at −80°C. Exclusions for the control population were any physician diagnosis of sinus disease or firefighters who had presented for evaluation of respiratory symptoms before March 2008 (24). To exclude chronic sinus disease, CRS diagnoses and dates were identified by searching the EMRs for International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, codes for chronic sinusitis (code 473.x), chronic rhinitis or nasopharyngitis (code 472.0/472.2), or polyps of the nose or sinus (code 471.x). Chronic disease was defined as at least two FDNY physician visits with one of these diagnoses at least 4 weeks apart. Serum IL-17A, IL-6, and IgA were evaluated by using multiplex assays (HSTCMAG28SPMX21 for IL-17A and IL-6, HGAMMAG-301K for IgA; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA), and IgE was assessed with a single-plex assay (HGAMMAG-303E; EMD Millipore). To avoid batch bias, equal proportions of cases and controls were included in each batch.

Statistical Analysis

All reported P values are two sided. Characteristics between the cohort and the surgical-CRS group were assessed using score tests for continuous variables and log-rank tests for categorical variables. Follow-up time for CBC was calculated from the first to the last medical monitoring CBC for each study participant. Follow-up time for surgical-CRS began on 9/11 and ended on the date of surgical-CRS. For active FDNY members without surgical-CRS, follow-up time ended on March 10, 2015. For retirees without surgical-CRS, follow-up ended at the last FDNY-WTCHP monitoring examination or treatment date. Rates for surgical-CRS included cases occurring after 9/11.

Cox proportional hazards models for multivariable analysis of rates, adjusted for race, were used to assess the effect of WTC exposure (initial arrival time, and work duration at the site), smoking, and eosinophil levels, and stratification by smoking status was used to assess the effect modification by smoking. Kaplan–Meier curves for single-variable assessment of eosinophils in the top quartile, initial arrival time, and work duration at the site on surgical-CRS were produced by setting all other covariates on the Cox model at their mean.

In the biomarkers substudy, stratified multivariable linear models analyzed predictors of eosinophil concentration in surgical-CRS patients and control subjects. All data analyses were performed with SPSS version 22 software (IBM, Armonk, NY) and replicated using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Characteristics of the Study Cohort, Surgical-CRS and Medical-CRS Patients

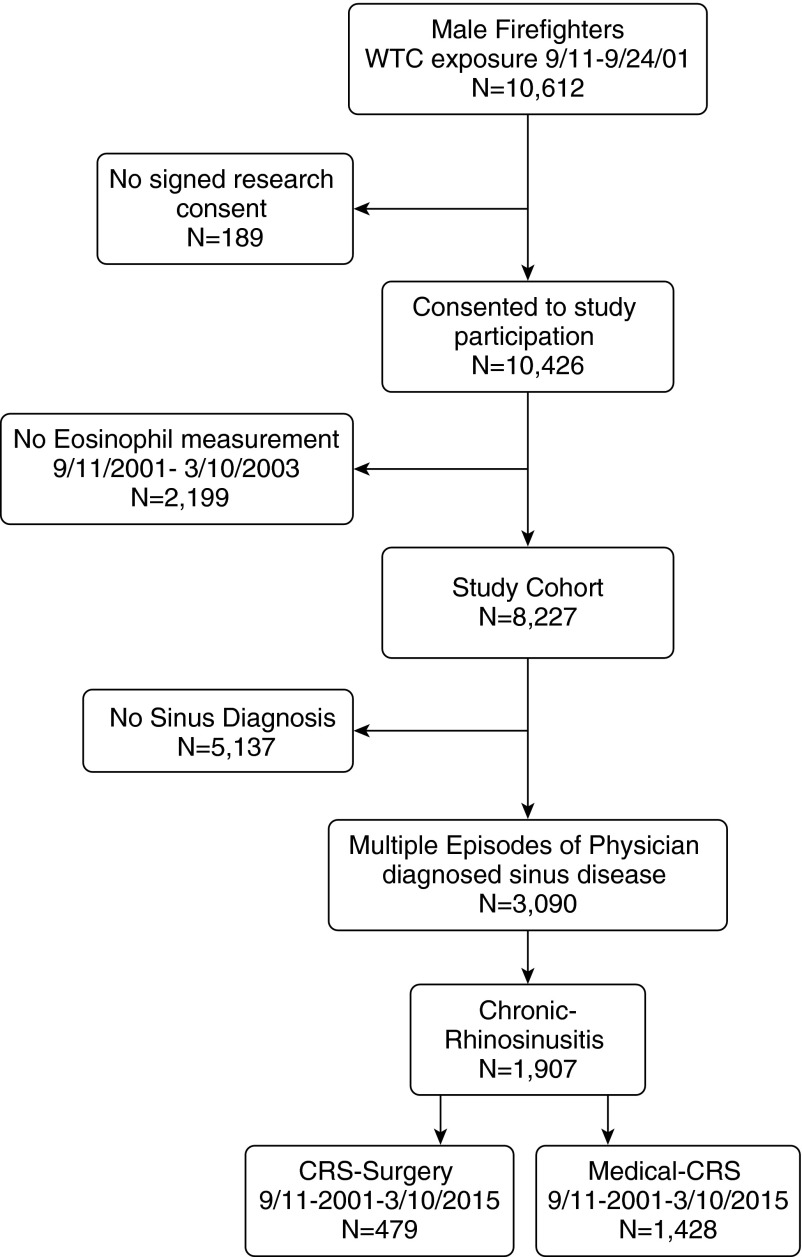

Figure 1 shows the parent population of 10,612 FDNY male firefighters who were first present at the WTC site between 9/11 and September 24, 2001. The final consented study cohort consisted of 8,227 firefighters, the 1,907 with objectively confirmed CRS, the 479 who were treated with surgery within 13.5 years of 9/11 (surgical-CRS), and the 1,428 who were medically managed (medical CRS) up to March 10, 2015.

Figure 1.

Study population of firefighters who participated in the World Trade Center (WTC) study. Shown are the number of male firefighters who were employed by the Fire Department of New York City on September 11, 2001, who were present at the WTC between September 11 and September 24, 2001 and are included in the study group; the number who had physician-diagnosed chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS); and the number who underwent sinus surgery between September 11, 2001, and March 10, 2015.

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of all exposed firefighters who consented to research, the study cohort, those with confirmed CRS, enumerating medical CRS and surgical-CRS subgroups, and the biomarker substudy subjects without a sinus diagnosis (control subjects) and surgical-CRS patients. The study cohort was similar to all exposed male firefighters: mostly white, never smokers, and usually arrived at the WTC site on 9/11 or September 12, 2001. Compared with the study cohort, surgical-CRS patients had higher blood eosinophil concentrations, were younger, had a lower percentage of ever smokers, arrived at the WTC site earlier, and had a longer duration of work at the WTC site and earlier diagnosis of sinus disease.

Table 1.

Study group demographics

| WTC-exposed Firefighters (n = 10,426) | Study Cohort (n = 8,227) | CRS (n = 1,907) | Medical-CRS (n = 1,428) | Surgical-CRS (n = 479) | Biomarker Substudy |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Subjects (n = 376) | Surgical-CRS (n = 112) | ||||||

| Age on 9/11, mean ± SD | 40.3 ± 7.4 | 40.0 ± 7.4* | 38.9 ± 6.6 | 39.1 ± 6.7† | 38.3 ± 6.2 | 40.5 ± 8.0 | 39.1 ± 5.5 |

| Race, n (%) | |||||||

| White | 9,788 (93.9) | 7,721 (93.9) | 1,816 (95.2) | 1,355 (94.9) | 461 (96.2) | 351 (93.4) | 107 (95.5) |

| African American | 264 (2.5) | 204 (2.5) | 26 (1.4) | 22 (1.5) | 4 (0.8) | 8 (2.1) | 0 |

| Hispanic | 344 (3.3) | 279 (3.4) | 59 (3.1) | 46 (3.2) | 13 (2.7) | 16 (4.3) | 5 (4.5) |

| Other | 30 (0.3) | 23 (0.3) | 6 (0.3) | 5 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Ever smokers, n (%) | 3,932 (37.7) | 3,028 (36.8) | 635 (33.3) | 488 (34.2) | 147 (30.7) | 0 | 0 |

| WTC arrival time, n (%) | |||||||

| 9/11–9/12 | 9,137 (87.6) | 7,190 (87.4) | 1,742 (91.4) | 1,303 (91.3) | 439 (91.6) | 348 (92.5) | 104 (92.9) |

| After 9/12 | 1,289 (12.4) | 1,037 (12.6) | 165 (8.6) | 125 (8.7) | 40 (8.4) | 28 (7.5) | 8 (7.1) |

| WTC work duration, n (%)‡ | |||||||

| 1 mo | 2,963 (28.4) | 2,407 (29.3) | 431 (22.6) | 332 (23.3) | 99 (20.7) | 129 (34.3) | 31 (27.7) |

| 2-5 mo | 4,939 (47.4) | 3,860 (46.9) | 887 (46.5) | 664 (46.5) | 223 (46.6) | 149 (39.6) | 44 (39.3) |

| ≥6 mo | 2,524 (24.2) | 1,960 (23.8) | 589 (30.9) | 432 (30.2) | 157 (32.8) | 98 (26.1) | 37 (33.0) |

| Eosinophils/ml 18 mo post-9/11 | N/A | 191 ± 134* | 200 ± 135 | 194 ± 128§ | 219 ± 155 | 174 ± 108 | 218 ± 159 |

| Years to first sinus diagnosis | 7.6 ± 3.6 | 7.6 ± 3.6 | 7.8 ± 3.6 | 8.1 ± 3.6§ | 6.7 ± 3.3 | N/A | 6.9 ± 3.4 |

| Years to CRS surgery | 8.7 ± 2.8 | 8.7 ± 2.9 | 8.7 ± 2.9 | N/A | 8.7 ± 2.9 | N/A | 8.7 ± 2.9 |

Definition of abbreviations: CRS = chronic rhinosinusitis; WTC = World Trade Center.

P < 0.0001 score test between study cohort and surgical-CRS.

P < 0.05 between medical CRS and surgical-CRS by t test.

P < 0.001 by log-rank test.

P < 0.001 between medical-CRS and surgical-CRS by t test.

Compared with the study cohort, medical-CRS patients were similar in age, eosinophil concentration, and time to diagnosis of sinus disease, but they had arrived at the WTC site earlier and had a longer duration of work at the WTC site. The biomarker substudy contained only never smokers; substudy surgical-CRS patients were similar to all surgical-CRS patients.

Risk Factors for Surgical-CRS

We used the longitudinal database of the FDNY-WTCHP to identify external exposures and patient intrinsic characteristics that altered sinus surgery rates when compared with the cohort. Table 2 shows multiple-predictor Cox regression models predicting surgery adjusted for age, race, and smoking history. Increasing eosinophil concentration (100 cells/μl) (hazard ratio [HR], 1.12; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.07–1.17; P < 0.001), earlier WTC arrival time (HR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.04–1.99; P = 0.03), and longer work duration at the WTC site (HR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.14–1.93; P < 0.01) were all associated with higher incidence of surgery. To better understand the impact of smoking, we tested for interaction between smoking and other risk factors and found none.

Table 2.

Cox proportional hazards predicting chronic rhinosinusitis surgery

| Full Cohort (n = 8,227) |

Smoking Stratified Model |

Biomarker Substudy (n = 488) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P Value | Never Smoker (n = 5,199) |

Ever Smoker (n = 3,028) |

HR | 95% CI | P Value | |||||

| HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value | |||||||

| Increasing Eos/100 cells/μl | 1.12 | 1.07–1.17 | <0.001 | 1.12 | 1.06–1.19 | <0.001 | 1.13 | 1.05–1.22 | 0.001 | 1.23 | 1.08–1.41 | 0.003 |

| Early WTC-site arrival | 1.43 | 1.04–1.99 | 0.03 | 1.22 | 0.84–1.77 | 0.29 | 2.18 | 1.11–4.29 | 0.023 | 0.88 | 0.42–1.82 | 0.73 |

| WTC-site work duration | ||||||||||||

| 1 mo | Reference |

Reference |

Reference |

Reference |

||||||||

| 2–5 mo | 1.09 | 0.85–1.40 | 0.49 | 0.94 | 0.70–1.27 | 0.69 | 1.49 | 0.94–2.36 | 0.088 | 0.89 | 0.53–1.48 | 0.65 |

| ≥6 mo | 1.48 | 1.14–1.93 | 0.003 | 1.42 | 1.05–1.94 | 0.024 | 1.58 | 0.95–2.61 | 0.077 | 1.18 | 0.70–1.98 | 0.54 |

| Age, yr | 0.98 | 0.97–0.99 | 0.003 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.00 | 0.12 | 0.97 | 0.95–0.99 | 0.007 | 0.98 | 0.95–1.01 | 0.16 |

| Ever smoker | 0.80 | 0.65–0.97 | 0.022 | |

|

|

||||||

| Increasing IL-6, pg/ml | |

|

|

0.84 | 0.72–0.97 | 0.02 | ||||||

| Increasing IgE, ng/ml | 1.01 | 0.99–1.03 | 0.23 | |||||||||

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; WTC = World Trade Center.

We then stratified subjects by smoking status and found that increasing eosinophil concentration remained a significant risk factor for surgical-CRS in both never smokers (HR, 1.12; P < 0.001) and ever smokers (HR, 1.13; P = 0.001). Early arrival remained significant only in ever smokers (HR, 2.18; 95% CI, 1.11–4.29; P = 0.023; vs. HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 0.84–1.77; P = 0.29). Further, ever smokers had higher eosinophils in than never smokers (213 ± 139 vs. 194 ± 133; P = 0.003 for CRS; 240 ± 166 vs. 209 ± 148; P = 0.046 for surgical-CRS). Since smoking confounds the association between surgical-CRS hazard and eosinophils, ever smokers were excluded from subsequent models to eliminate this confounding.

We performed a biomarker substudy of 488 individuals with serum drawn within 6 months after WTC exposure, comparing risk factors for sinus surgery in 112 surgical patients and 376 control subjects using IgE concentration as a biomarker for atopic disease. The control group excluded those with upper and lower respiratory diagnoses that could be associated with atopy. While eosinophil concentration and age remained significant risk factors for surgical-CRS, IgE was not associated with surgical-CRS (HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.99–1.03; P = 0.23). Consistent with our prior study with different cases and controls (23), IL-6 reduced hazard of surgical-CRS (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.72–0.97; P = 0.021).

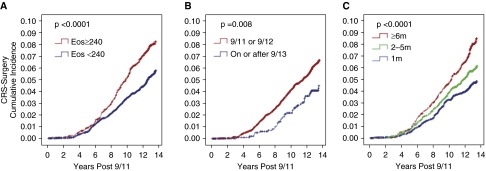

With the cohort as the reference, we used Kaplan–Meier analysis to illustrate the effect of risk factors on surgical-CRS. As opposed to the Cox models that used eosinophils as a continuous variable, the Kaplan–Meier analysis used the top quartile of eosinophils (240 cells/μl) in the cohort to demonstrate the effect of higher eosinophils.

Figure 2 shows cumulative incidence plots for surgical-CRS as a function of blood eosinophil concentration, WTC arrival time, and WTC-site work duration. Higher levels of eosinophils were associated with higher rates of surgical-CRS (P < 0.001), as were earlier arrival times (P < 0.01) and WTC-site work duration (P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of surgical chronic rhinosinusitis (surgical-CRS) cases from September 11, 2001, to March 10, 2015, in firefighters who worked at the World Trade Center (WTC) site during the first 2 weeks after 9/11 by blood eosinophil (Eos) concentration (A), WTC-site arrival time (B) and WTC-site work duration (C). (A) The cumulative incidence of surgical-CRS cases after the cohort was stratified by blood eosinophil concentration above and below 240 cells per microliter, the top quartile in the 18 months post-9/11. (B) The cumulative incidence of surgical-CRS cases after the cohort was stratified by initial WTC-site arrival time, either within the first 2 days of 9/11 or after September 12, 2001. (C) The cumulative incidence of surgical-CRS cases after the cohort was stratified by months of WTC rescue and recovery work: 1 month, 2–5 months, and 6 or more months.

Predictors of Eosinophil Concentration

Biological differences between the surgical-CRS patients and the study cohort could explain the impact of eosinophil concentration on surgery rates. To gain insight into immunological pathways associated with elevated eosinophil concentration in surgical-CRS patients, we performed multivariable linear regression with eosinophil concentration 1.6–6.3 months post-9/11 as the outcome and inflammatory biomarkers measured in serum from the same venipuncture as the eosinophil concentration as the predictor.

Table 3 shows two multivariable linear regressions with post-9/11 eosinophil concentration as the outcome. IL-17A is strongly correlated with eosinophil concentration in surgical-CRS patients but not in controls (standardized β, 0.428; P < 0.0001; vs. standardized β, −0.06; P = 0.23). Similarly, age and low serum IgA positively correlated with eosinophil concentration only in surgical-CRS patients. Alternately, surgical-CRS patients had a trend for higher eosinophil concentration soon after exposure, with decline over time (28.6 ± 16.7 cells/mo decline; P = 0.093).

Table 3.

Linear models predicting eosinophils cells per microliter in post-9/11 blood*

| CRS Surgery (n = 112)† |

No Sinus Disease (n = 376)‡ |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Value | SE | Standardized β-Value | P Value | β-Value | SE | Standardized β-Value | P Value | |

| Age, yr | 6.67 | 2.42 | 0.23 | 0.007 | −0.18 | 0.71 | −0.01 | 0.80 |

| IL-17A, pg/ml | 1.15 | 0.22 | 0.43 | <0.001 | −0.27 | 0.23 | −0.06 | 0.23 |

| IgA ≤300 ng/ml | −108.45 | 40.28 | −0.23 | 0.008 | 3.85 | 16.28 | 0.01 | 0.81 |

| Months to examination | −28.60 | 16.72 | −0.15 | 0.09 | 5.42 | 5.48 | 0.05 | 0.32 |

Definition of abbreviations: CRS = chronic rhinosinusitis.

From 1.5 to 6 months post-9/11.

Model R2 = 0.26; P < 0.0001. P value after Bonferroni correction.

Model R2 = 0.008; P = 0.56.

In the control group, there was no impact of time postexposure on eosinophil concentration (5 ± 5 cells/mo increase; P = 0.32). Age, IL-17A, low IgA, and time postexposure explained 26% of the observed variance in surgical-CRS patients’ eosinophil concentration (R2 = 0.26; P < 0.0001). These four variables had no association with eosinophils in control subjects (R2 = 0.008; P = 0.56).

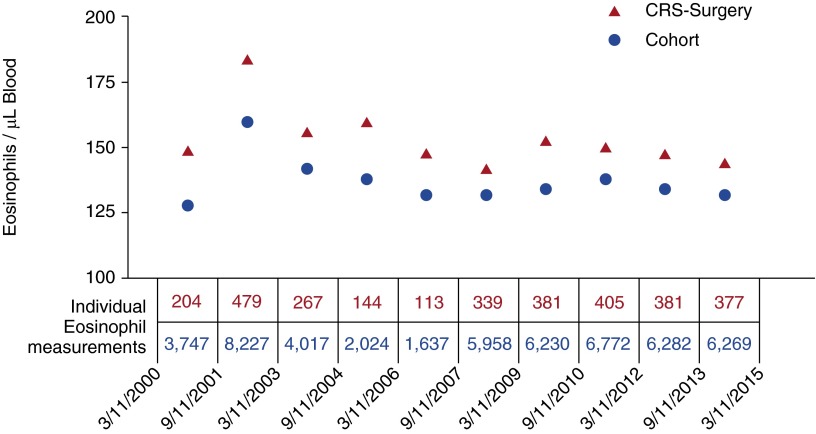

Longitudinal Eosinophil Concentration in the Study Cohort and Surgical-CRS

Examination of eosinophil concentration and biomarkers obtained soon after WTC exposure suggests biological differences between surgical-CRS patients and other subgroups in the study cohort. The FDNY-WTCHP has preexposure data as well as compressive longitudinal data on eosinophil concentration. We therefore explored if differences in surgical-CRS patients’ concentrations existed before exposure or extended beyond the initial insult.

Figure 3 shows median eosinophil concentrations from March 10, 2000, to March 10, 2015, representing 97,733 person-years of follow-up in 18-month intervals. The surgical-CRS patients had higher eosinophils than the study cohort at every time interval, including pre-9/11. Analyzing results from a subset of 2,444 who had blood drawn 18 months pre-9/11, in the first 18 months post-9/11, and during the 36 months between March 11, 2003, and March 10, 2006, we found that the pre-9/11 eosinophils were 126 cells per microliter (interquartile range [IQR], 78–198), increased to 160 cells per microliter (IQR, 108–244) in the first 18 months post-9/11, and then declined to 144 cells per microliter (IQR, 90–216) in the following 36 months (P < 0.001 for both comparisons). In the 158 surgical patients with values in all time intervals, the pre-9/11 eosinophils were 149 cells per microliter (IQR, 84–238), increased to 179 cells per microliter (IQR, 120–251) in the first 18 months post-9/11, and then declined to 162 cells per microliter (IQR, 96–243) in the following 36 months (P < 0.001 and P = 0.001, respectively).

Figure 3.

Blood eosinophil concentration in firefighters who worked at the World Trade Center site during the first 2 weeks after 9/11 according to surgical chronic rhinosinusitis (surgical-CRS) status. Shown are the median eosinophil concentrations from March 10, 2000, to March 10, 2015, in 18-month intervals. The blue dots show data for Fire Department of New York City firefighters who worked at the World Trade Center site during the first 2 weeks after the attack of September 11, 2001, and who had eosinophil measurements between September 11, 2001, and March 10, 2003. The red triangles show data from the group that had surgical-CRS by the end of the study. The number of measurements contributing to the values in each interval are shown below each data point. The top row of values show in red represents the number of eosinophil measurements in the surgical-CRS group. The bottom row of values show in blue represents the number of eosinophil measurements in the study cohort.

Discussion

We present 13.5 years of post-9/11 longitudinal follow-up for 8,227 firefighters who sustained intense, caustic dust exposure from the WTC towers collapse and participated in subsequent rescue and/or recovery operations. Those who proceeded to sinus surgery had elevated blood eosinophil concentrations before exposure. Further, only those who underwent sinus surgery had an association between IL-17A or low IgA and eosinophil concentration after exposure.

These data are consistent with immunological differences between those who proceeded to sinus surgery and the rest of the cohort that were evident years before disease presentation. Since both acute and chronic exposure to the WTC site were significant risk factors for surgical-CRS, there is a need for usable and effective respiratory protection during long-term rescue or recovery work at future disaster sites. As this is often difficult to achieve, blood eosinophils obtained before or immediately after exposure could identify those who might benefit the most from early monitoring and targeted treatment. Blood eosinophil concentration is a widely available, well-studied biomarker of upper and lower respiratory disease that is inexpensive, externally valid, and currently collected in many longitudinal cohorts (13, 22, 25).

Those firefighters who underwent sinus surgery had higher blood eosinophil levels than the study cohort throughout the study period, including pre-9/11, suggesting that an elevated eosinophil set point is intrinsic to this vulnerable group. Surprisingly, those with medical-CRS had eosinophil concentrations similar to those of the cohort and significantly below the surgical-CRS patients.

Eosinophil blood levels increased after 9/11. The acute increase likely reflects the systemic response to acute innate inflammation. However, blood eosinophil concentration declined after the first postexposure 18-month interval and trended to the preexposure equilibrium after several years.

Exposed firefighters with elevated blood eosinophil concentrations had an 8.4% cumulative incidence of sinus surgery over 13.5 years, compared with 5.9% for those with eosinophil levels in the bottom three-fourths of the distribution, This resulted in a 45% increased risk of surgical-CRS in the multivariable Cox regression model using data from the whole study cohort. Only 20 (4%) of 479 of the surgical-CRS cases had eosinophil concentrations above 500 cells per microliter in the first 18 months after exposure, indicating that a vast majority of those who proceeded to nonresolving upper airway inflammation had normal early eosinophil concentrations.

The biomarker component of this investigation did not identify an association between IgE and surgical-CRS. This is different from exposed FDNY firefighters with a lower airway diagnosis, where IgE is a significant risk factor (26). The biomarker data suggest that atopy was not a large contributor to surgical-CRS in this cohort.

Consistent with our prior observations and recent reports, increasing IL-6 reduced surgical-CRS hazard (23, 27). Importantly, increasing IL-17A and age, along with low IgA concentration, were associated with eosinophils only in surgical-CRS patients and not in controls. IL-17A is expressed by excised nasal polyp tissue and correlates with tissue eosinophil (19, 28, 29). Low IgA concentration is a known risk factor for sinus disease (30). Further research is needed to define the underlying mechanism of the differences in mucosal immunity between surgical-CRS patients and those who do not proceed to surgery.

Increasing acute and chronic particulate exposure are strong risk factors for surgical-CRS, demonstrating a link between surgical-CRS and work at the WTC site. The upper airway protects the lungs by adsorbing “large” particles from inhaled air. This filtering role renders the upper airway vulnerable to caustic dust exposure.

Compared with arrival at the WTC site on or after September 13, 2001, those who arrived on 9/11 or September 12 had a 45% increased risk of surgical-CRS. This results in a 6.6% cumulative incidence of surgical-CRS over 13.5 years in the early-arrival group compared with 4.6% in the late-arrival group. Compared with working at the site for 1 month, those who engaged in WTC rescue or recovery work for 6 or more months had a 48% increased risk of surgical-CRS. This results in an 8.7% cumulative incidence of surgical-CRS over 13.5 years in the prolonged exposure group compared with 4.9% in the briefer exposure group.

The combined effect of early acute injury followed by chronic, persistent exposure predisposes these workers to nonresolving inflammation and surgical-CRS years later. The impact of early arrival is most pronounced in smokers, a subgroup with preexisting upper airway inflammation.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. FDNY firefighters may not be representative of the larger population of non-FDNY WTC-exposed individuals. First, the FDNY study cohort is overwhelmingly male and previously healthy and experienced a massive particulate exposure. This analysis identified risk factors for the most common pathways to surgical-CRS and likely missed risk factors for less common pathways to disease in this population.

It is likely that atopy is an underrepresented pathway to sinus disease in this population. Asthma precludes work as a firefighter, and most of the WTC-exposed patients had irritant-induced symptoms with no biomarker evidence of atopy within 18 months of exposure and little clinical evidence of an allergic component at presentation. Low levels of atopy are especially likely in the biomarker control population that excluded both upper and lower airway diseases to increase the likelihood of identifying atopy in the surgical-CRS patients. Nevertheless, a wide range of findings in the FDNY cohort has been replicated in other WTC-exposed cohorts.

Second, this study was designed to assess early predictors of surgical-CRS risk, so subsequent events, such as repeated irritant exposures or treatment before surgery, were not studied. Third, the data represent risk factors obtained before disease, reducing the potential for “reverse causation,” but none of the eosinophil or other biomarker data imply a causal relationship to disease. The longitudinal eosinophil analysis and biomarker data suggest that surgical-CRS patients are biologically different in one or more of the innumerable pathways impacting blood eosinophil concentration when compared with the cohort or biomarker controls. Association of increased IL-17A and reduced IgA levels with eosinophils could be a result of the early immune response in those predisposed to nonresolving inflammation or could cause nonresolving inflammation resulting in surgical-CRS. In spite of these limitations, the FDNY-WTCHP is a valuable resource for understanding irritant-induced diseases such as CRS in the occupational setting, where there is little available data (31, 32).

Conclusions

Acute and chronic WTC exposure were risks for nonresolving upper airway inflammation, with recurrent CRS responding poorly to medical management that ultimately was treated with surgery years later. Increasing eosinophils served as a biomarker for a population that had increased vulnerability to upper airway injury after WTC exposure. The finding that increasing eosinophils was associated with increased rates of surgical-CRS supports earlier observations linking eosinophilia with sinusitis in WTC-exposed children (13). Finally, surgical-CRS patients are likely predisposed to exaggerated inflammation and/or poor counterregulatory responses to inflammation (18–21).

In future disasters, improved respiratory protection during the rescue and/or recovery phase may be effective in reducing the hazard of difficult-to-treat CRS. Pathways to nonresolving inflammation are induced and/or sustained by repeated irritant exposures over months. Targeting these inflammatory pathways for intervention early in the disease evolution may yield more effective therapies. Further research is required to identify additional biomarkers of disease associated with above-average blood eosinophil concentration and develop more effective treatments for patients with CRS with persistent symptoms, despite currently available medical management.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) contracts 200-2011-39383 and 200-2011-39378, NIOSH grants U01 OH010726 (M.D.W.) and U01 OH010711, and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant R01 HL119326.

Author Contributions: Conception and design: A.N., D.J.P., M.D.W. Acquisition of data: M.H., D.M., M.R.S., A.N., K.J.K., D.J.P., M.D.W. Analysis and interpretation of data: S.K., B.P., J.W., C.B.H., R.Z.-O., T.S., B.O., A.S., M.P.W., H.W.C., T.K.A., A.N., D.J.P., M.D.W. Drafting or revising of article: S.K., B.P., J.W., C.B.H., M.P.W., H.W.C., T.K.A., A.N., D.J.P. Final approval of the manuscript: D.J.P., C.B.H., M.P.W., M.D.W.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Bhattacharyya N. Contemporary assessment of the disease burden of sinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2009;23:392–395. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhattacharyya N. Ambulatory sinus and nasal surgery in the United States: demographics and perioperative outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:635–638. doi: 10.1002/lary.20777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pleis JR, Lucas JW, Ward BW. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2008. Vital Health Stat 10. 2009;(242):1–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan BK, Chandra RK, Pollak J, Kato A, Conley DB, Peters AT, Grammer LC, Avila PC, Kern RC, Stewart WF, et al. Incidence and associated premorbid diagnoses of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:1350–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Mullol J, Bachert C, Alobid I, Baroody F, Cohen N, Cervin A, Douglas R, Gevaert P, et al. EPOS 2012: European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2012. A summary for otorhinolaryngologists. Rhinology. 2012;50:1–12. doi: 10.4193/Rhino12.000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jarvis D, Newson R, Lotvall J, Hastan D, Tomassen P, Keil T, Gjomarkaj M, Forsberg B, Gunnbjornsdottir M, Minov J, et al. Asthma in adults and its association with chronic rhinosinusitis: the GA2LEN survey in Europe. Allergy. 2012;67:91–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim YS, Kim NH, Seong SY, Kim KR, Lee GB, Kim KS. Prevalence and risk factors of chronic rhinosinusitis in Korea. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2011;25:117–121. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2011.25.3630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan BK, Kern RC, Schleimer RP, Schwartz BS. Chronic rhinosinusitis: the unrecognized epidemic. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:1275–1277. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201308-1500ED. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Künzli N, Kaiser R, Medina S, Studnicka M, Chanel O, Filliger P, Herry M, Horak F, Jr, Puybonnieux-Texier V, Quénel P, et al. Public-health impact of outdoor and traffic-related air pollution: a European assessment. Lancet. 2000;356:795–801. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02653-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nachman KE, Parker JD. Exposures to fine particulate air pollution and respiratory outcomes in adults using two national datasets: a cross-sectional study. Environ Health. 2012;11:25. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-11-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prezant DJ, Weiden M, Banauch GI, McGuinness G, Rom WN, Aldrich TK, Kelly KJ. Cough and bronchial responsiveness in firefighters at the World Trade Center site. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:806–815. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niles JK, Webber MP, Liu X, Zeig-Owens R, Hall CB, Cohen HW, Glaser MS, Weakley J, Schwartz TM, Weiden MD, et al. The upper respiratory pyramid: early factors and later treatment utilization in World Trade Center exposed firefighters. Am J Ind Med. 2014;57:857–865. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin S, Reibman J, Bowers JA, Hwang SA, Hoerning A, Gomez MI, Fitzgerald EF. Upper respiratory symptoms and other health effects among residents living near the World Trade Center site after September 11, 2001. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:499–507. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trasande L, Fiorino EK, Attina T, Berger K, Goldring R, Chemtob C, Levy-Carrick N, Shao Y, Liu M, Urbina E, et al. Associations of World Trade Center exposures with pulmonary and cardiometabolic outcomes among children seeking care for health concerns. Sci Total Environ. 2013;444:320–326. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.11.097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weakley J, Webber MP, Gustave J, Kelly K, Cohen HW, Hall CB, Prezant DJ. Trends in respiratory diagnoses and symptoms of firefighters exposed to the World Trade Center disaster: 2005–2010. Prev Med. 2011;53:364–369. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wisnivesky JP, Teitelbaum SL, Todd AC, Boffetta P, Crane M, Crowley L, de la Hoz RE, Dellenbaugh C, Harrison D, Herbert R, et al. Persistence of multiple illnesses in World Trade Center rescue and recovery workers: a cohort study. Lancet. 2011;378:888–897. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61180-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akdis CA, Bachert C, Cingi C, Dykewicz MS, Hellings PW, Naclerio RM, Schleimer RP, Ledford D. Endotypes and phenotypes of chronic rhinosinusitis: a PRACTALL document of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:1479–1490. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaw JL, Fakhri S, Citardi MJ, Porter PC, Corry DB, Kheradmand F, Liu YJ, Luong A. IL-33-responsive innate lymphoid cells are an important source of IL-13 in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:432–439. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201212-2227OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi LL, Song J, Xiong P, Cao PP, Liao B, Ma J, Zhang YN, Zeng M, Liu Y, Wang H, et al. Disease-specific T-helper cell polarizing function of lesional dendritic cells in different types of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:628–638. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201402-0234OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang XH, Zhang YN, Li HB, Hu CY, Wang N, Cao PP, Liao B, Lu X, Cui YH, Liu Z. Overexpression of miR-125b, a novel regulator of innate immunity, in eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:140–151. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0456OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stevens WW, Ocampo CJ, Berdnikovs S, Sakashita M, Mahdavinia M, Suh L, Takabayashi T, Norton JE, Hulse KE, Conley DB, et al. Cytokines in chronic rhinosinusitis: role in eosinophilia and aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:682–694. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201412-2278OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kazeros A, Maa MT, Patrawalla P, Liu M, Shao Y, Qian M, Turetz M, Parsia S, Caplan-Shaw C, Berger KI, et al. Elevated peripheral eosinophils are associated with new-onset and persistent wheeze and airflow obstruction in World Trade Center-exposed individuals. J Asthma. 2013;50:25–32. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2012.743149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho SJ, Echevarria GC, Kwon S, Naveed B, Schenck EJ, Tsukiji J, Rom WN, Prezant DJ, Nolan A, Weiden MD. One airway: biomarkers of protection from upper and lower airway injury after World Trade Center exposure. Respir Med. 2014;108:162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiden MD, Ferrier N, Nolan A, Rom WN, Comfort A, Gustave J, Zeig-Owens R, Zheng S, Goldring RM, Berger KI, et al. Obstructive airways disease with air trapping among firefighters exposed to World Trade Center dust. Chest. 2010;137:566–574. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malinovschi A, Fonseca JA, Jacinto T, Alving K, Janson C. Exhaled nitric oxide levels and blood eosinophil counts independently associate with wheeze and asthma events in National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:821–827.e1–e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cho SJ, Nolan A, Echevarria GC, Kwon S, Naveed B, Schenck E, Tsukiji J, Prezant DJ, Rom WN, Weiden MD. Chitotriosidase is a biomarker for the resistance to World Trade Center lung injury in New York City firefighters. J Clin Immunol. 2013;33:1134–1142. doi: 10.1007/s10875-013-9913-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho SH, Kim DW, Lee SH, Kolliputi N, Hong SJ, Suh L, Norton J, Hulse KE, Seshadri S, Conley DB, et al. Age-related increased prevalence of asthma and nasal polyps in chronic rhinosinusitis and its association with altered IL-6 trans-signaling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2015;53:601–606. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0207RC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Makihara S, Okano M, Fujiwara T, Kariya S, Noda Y, Higaki T, Nishizaki K. Regulation and characterization of IL-17A expression in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis and its relationship with eosinophilic inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:397–400.e1–e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saitoh T, Kusunoki T, Yao T, Kawano K, Kojima Y, Miyahara K, Onoda J, Yokoi H, Ikeda K. Role of interleukin-17A in the eosinophil accumulation and mucosal remodeling in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps associated with asthma. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2010;151:8–16. doi: 10.1159/000232566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vanlerberghe L, Joniau S, Jorissen M. The prevalence of humoral immunodeficiency in refractory rhinosinusitis: a retrospective analysis. B-ENT. 2006;2:161–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sundaresan AS, Hirsch AG, Storm M, Tan BK, Kennedy TL, Greene JS, Kern RC, Schwartz BS. Occupational and environmental risk factors for chronic rhinosinusitis: a systematic review. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015;5:996–1003. doi: 10.1002/alr.21573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Min JY, Tan BK. Risk factors for chronic rhinosinusitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;15:1–13. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]