Abstract

Dementia patients exhibit considerable heterogeneity in individual trajectories of cognitive decline, with some patients showing rapid decline following diagnoses while others exhibiting slower decline or remaining stable for several years. Dementia studies often collect longitudinal measures of multiple neuropsychological tests aimed to measure patients’ decline across a number of cognitive domains. We propose a multivariate finite mixture latent trajectory model to identify distinct longitudinal patterns of cognitive decline simultaneously in multiple cognitive domains, each of which is measured by multiple neuropsychological tests. EM algorithm is used for parameter estimation and posterior probabilities are used to predict latent class membership. We present results of a simulation study demonstrating adequate performance of our proposed approach and apply our model to the Uniform Data Set (UDS) from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) to identify cognitive decline patterns among dementia patients.

Keywords: Multivariate finite mixture latent trajectory, cognitive decline, dementia

1. Introduction

Dementia is common in the elderly population, with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) the leading cause. [1]. It is characterized by the progressive decline of cognitive function, leading to impairment in the individual’s ability to perform daily activities and the consequent loss of independence. There is considerable heterogeneity in the individual trajectories of cognitive decline among dementia patients, with some patients showing rapid decline while others exhibiting a slower decline or remaining stable [2]. The heterogeneity of the cognitive decline also varies across cognitive domains such as memory and language. Prior research has shown that typical patients with AD have primarily memory deficits often accompanied by deficits in language [3–5], whereas patients with frontotemporal dementia (FTD) had greater impairment in language and less impairment in the memory domain [6–10].

Research on the identification of distinct longitudinal trajectories of cognitive decline has focused on univariate cognitive outcomes, measured by a single neuropsychological test using group-based trajectory models (GBTM) [11–13] and growth mixture models (GMM) [14–16]. GBTM is also known as latent class growth analysis (LCGA) [15] and was proposed by Nagin and colleagues [11–13] while GMM was developed by Muthén et al [14–16]. Both models assume that subjects belong to one of several subpopulations/groups/latent classes, each characterized by a unique longitudinal trajectory. A key difference between GBTM and GMM is that GBTM assumes conditional independence, i.e. longitudinal measures across time for a given subject are independent, whereas the GMM includes a random effect allowing correlation of longitudinal outcomes for a subject [15]. Therefore, GBTM can be considered a special case of GMM [15].

Despite the successful application of the GBTM and GMM models in many research studies [12, 15], these models are not well-suited for the longitudinal analyses of dementia due to the fact that each latent construct can only be from one test. Many studies of cognitive decline in dementia patients have collected data across several cognitive domains with multiple neuropsychological tests in each domain. Tests within each domain are measures of same underline latent construct from different prospective. Proust-Lima and colleagues extended the GBTM and GMM models to multivariate longitudinal data by treating the multiple tests as reflecting a single unobserved quantity following a latent process that exhibits distinct longitudinal patterns across groups [17, 18]. Although this approach has the flexibility to handle multivariate cognitive outcomes, it allows only exploration of the longitudinal patterns of a single underlying quantity and does not make use of the full capability of the models. In dementia studies where many neuropsychological tests are used to measure different aspects of cognitive function including memory, language, and executive function, it is more realistic to assume multiple latent quantities and identify longitudinal patterns associated with these various cognitive domains.

In this paper, we extend the model proposed by Proust-Lima et al by allowing more than one latent quantity, each of which can be measured by multiple tests, and identifying subpopulations of patients who exhibit distinct longitudinal patterns in these latent quantities. Our work was directly motivated by studies of cognitive decline among dementia patients. Our proposed approach is aimed at identifying longitudinal patterns of cognitive decline defined in multiple cognitive domains. The identified sub-populations share the similar cognitive decline patterns therefore may share the same disease etiology; thus, it can help us to find better patient care and treatment. In addition, these phenotypically homogeneous sub groups can be used to improve the ability of searching dementia genes in genetic studies.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we introduce the multivariate finite mixture latent trajectory model. We discuss parameter estimation using the EM algorithm Section 3. We present results from simulation studies in Section 4. Section 5 includes results from the application of our model to the Uniform Data Set (UDS) from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) [19]. We present a discussion and conclude the paper in section 6.

2. The Multivariate Finite Mixture Latent Trajectory Model

Assume that the population consists of G subpopulations represented by G latent classes. For individual i, i = 1, …, N, we define a G-dimentional vector ωi denoting the latent class membership, with ωig = 1 if individual i belongs to class g and 0 otherwise. Suppose there are K neuropsychological tests with continuous outcomes representing cognitive function in D cognitive domains. Let be the vector of all measurements for individual i. yik is then a vector of length nik, which denotes the number of longitudinal measurements on individual i for test k (k = 1, …, K); hence the length of yi is . Let X1i(t) and Zi(t) be the matrices of covariates collected for individual i. Zi(t) can have partial or all columns of X1i(t) but contains at least one time variable. Then a measurement model if individual i is in latent class g is:

| (1) |

Where the latent trajectory is defined as:

| (2) |

The length of latent process Λi|ωig = 1(t) is also . Note that tests in the same domain share the same latent process by having the same values in Λi|ωig = 1(t). βg is the vector of class-specific fixed effects from all cognitive domains in latent class g. Its length is P × D, where P is the number of covariates. big is the class-specific random effects for all domains in latent class g. Similar to βg, big has length q × D, where q is the number of random effects. We assume that big has a multivariate normal distribution with and B is the covariance matrix of the first latent class, similarly defined as in Proust et al [17]. ci in (1) is the K-vector of test-specific random intercept. It introduces correlation among scores of the same test from the same individual. Here we assume ci is distributed as N(0, Σc), where Σc is a diagonal matrix with in its diagonal. Design matrix Vi in (1) is a block matrix with the following structure:

where 1 is a column vector of 1s. In the kth column, the column vector of 1s has length nik. εi in (1) is a vector of random errors with distribution N(0, Σε), where Σε is a block matrix with on the diagonal and all other entries are 0.

Accordingly, covariate matrix X1i(t) has the following structure:

Each X1id has all covariates for all the tests comprising domain d, d = 1, …, D with dimension nik × P. Similarly the design matrix Zi(t) has the following structure:

where Zid is a matrix of time polynomials of degree q − 1 with dimension nik × q. For example, if nik = 3, for a quadratic model, each Zid has structure as follows:

Note that, although individuals typically have the same measurement times, this is not required for our proposed model. Based on the definition of X1i(t) and Zi(t), individuals can have tests measured at different time points.

We assume that big, ci and εi are mutually independent.

For individual i, i = 1, …, N, the probability that this individual belongs to a latent class g, g = 1, …, G, is πig, with . This can be modeled through a multinomial logistic regression as:

| (3) |

where γg is the vector of the class-specific regression coefficients. For identifiability purposes, γG are set to 0. Covariates used here can be the same or different from X1i(t) in equation (2).

3. Parameter Estimation

Since the latent class memberships are unobserved and there are also multiple random effects, the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm can be used for obtaining parameter estimates [20–23]. Let be the parameters to be estimated, and fig(yi) be the density function of yi in latent class g; then the observed-data likelihood is:

| (4) |

fig(yi) has distribution N(X1i(t)βg, Σig), where .

Augmenting the observed data yi with unobserved variables (ωi, bi1 …, big, …, biG, ci), the complete-data likelihood function is:

The log-likelihood for the complete data is

| (5) |

where l is the dimension of square matrix B.

3.1. The EM algorithm

The EM algorithm involves taking the conditional expectation of the complete-data log-likelihood and updating the parameters by maximizing the conditional expectation. Based on (5), we can see that the E step at oth iteration involves evaluating the following conditional expectations for each subject:

Calculation of the first conditional expectation is straightforward:

| (6) |

which is the posterior probability of subject i belonging to latent class g at the current parameter estimate.

In addition,

Therefore, similarly, we only need to calculate:

The joint distribution of is a multivariate normal distribution with mean:

and variance matrix:

Let and ; therefore the joint distribution of big, ci conditional on yi is a multivariate normal distribution with mean

| (7) |

And variance-covariance matrix

| (8) |

From (8) above:

| (9) |

Thus, all conditional expectations can be obtained from (9).

Implementing the M-step is relatively trivial since there exists a closed-form solution to the maximization of the conditional expectation of the complete-data log-likelihood for the majority of the parameters except for in the model for , which has to be updated numerically. For all other parameters, closed-form solutions are available and are given below:

The E-step and M-step will be repeated until the difference of observed likelihood becomes smaller than a pre-specified threshold. For model fitting and parameter estimation we used SAS PROC IML. Initial parameter estimates used in the iterative program were obtained using SAS PROC NLMIXED without any random effects. To avoid local maxima, different initial parameter values around the estimates from PROC NLMIXED were used. Variance covariance matrix was calculated using the negative inversion of Hessian matrix by using the SAS function NLPFDD through the finite-differences method.

3.2 Posterior classification and model selection

Assignment of each subject into a latent class can be achieved using the posterior probability defined in (6) and estimated based on the maximum likelihood estimates of the parameters. As can be seen from (6), group membership is jointly determined by both probabilities in each group and group specific latent trajectories [12]. A subject is classified in the latent class for which he or she has the highest posterior probability [12]. While this class assignment appears subjective, it was shown to be an optimal choice under the normal distribution assumption in terms of minimizing the probability of error, i.e., assigning the subject to the wrong class [24]. If the normal distribution assumption is violated, this method of assignment may not retain its optimal property. Other classification approaches may be explored including the K-nearest neighbor classification method and random assignment [25, 26]. These posterior probabilities are then used to evaluate the degree to which the latent classes can be distinguished by the data [27]. Specifically, we will calculate a G × G classification table, with each row representing the average posterior probabilities for each latent class among subjects assigned to a given latent class [27]. High diagonal values close to 1 and low off-diagonal values close to 0 indicate good classification quality.

The number of latent classes for each data set is unknown and needs to be pre-specified before each model estimation procedure. Many model selection procedures can be used to select the ‘best’ model when varying numbers of latent classes are used. In this study, Bayesian information criterion (BIC) [28] will be used to select the number of latent classes. Although there has been conflicting conclusions about its performance [12, 20, 29–31], BIC has been found to have superior performances in several studies [12, 29]. With its ease to implement, BIC has been recommended by many researchers to select the number of latent class [12, 13, 15].

4. Simulation Studies

For the simulation study, we focused on parameter estimation and latent class classification, i.e., whether we can identify the true trajectories and assign individuals into the correct latent classes. Data were simulated under two cognitive domains with two tests in each domain. For each domain, linear trajectory was assumed. In addition to a time variable, a binary variable and a continuous variable were simulated as covariates for the domain specific fixed effects. For class specific random effects, both intercept and slope were assumed. To determine the latent class membership, one continuous variable was simulated. We designed the simulation studies to mimic longitudinal data arising from medical research, which usually contain missing data. Each sample was first simulated to have measurements at three time points and test scores at one to two time points were then randomly set to be missing for some randomly chosen samples.

Five scenarios with 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 latent classes were simulated. For each scenario, we generated 500 replications with each replication consisting 1500 subjects. Under each scenario we fitted a latent trajectory model with the true number of latent classes, e.g., for data that consist of 4 latent classes, only the 4-class model was fitted.

Table 1 shows the resulting parameter estimates for the two-class model. It appears that our proposed method yields adequate parameter and standard error estimates for all model parameters. Similar results were obtained for the 3 to 6-class models (Appendix). Table 2 includes average coverage probabilities of 95% confidence intervals for all model parameters and misclassification rates. Coverage estimates are defined as the percentage of times that the 95% confidence interval of a parameter estimate contains the true parameter across all replications. Misclassification rate is calculated as the percentage of samples that are assigned to the wrong latent class according to the posterior probability. In our simulations, misclassification rates ranged from near 0 to 13.97%, with misclassification rates tending to increase with the number of latent classes. This is expected since there is more opportunities for classification error when there are more latent classes. In addition, for a fixed sample size, as the number of latent classes increases, the number of samples within each latent class decreases, leading to increased standard error estimates of class-specific parameters. Classification error thus increases with less well- separated classes.

Table 1.

Mean parameter estimates, asymptotic standard error (SE) and empirical standard error from 500 replications in simulations for a two-class model

| Parameter | True Value |

Mean estimates |

Asymptotic SE |

Empirical SE |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ11 | 6.00 | 6.02 | 0.32 | 0.32 | |

| γ12 | −12.00 | −12.05 | 0.61 | 0.62 | |

| β11 | 5.60 | 5.58 | 0.13 | 0.13 | |

| β12 | 1.60 | 1.57 | 0.04 | 0.05 | |

| β13 | 1.60 | 1.60 | 0.12 | 0.12 | |

| β14 | 1.60 | 1.60 | 0.19 | 0.20 | |

| β15 | 1.20 | 1.18 | 0.13 | 0.14 | |

| β16 | 1.20 | 1.16 | 0.04 | 0.06 | |

| β17 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 0.13 | 0.13 | |

| β18 | 1.20 | 1.19 | 0.20 | 0.22 | |

| β21 | −5.60 | −5.58 | 0.13 | 0.13 | |

| β22 | −1.60 | −1.56 | 0.04 | 0.05 | |

| β23 | −1.60 | −1.60 | 0.12 | 0.12 | |

| β24 | −1.60 | −1.60 | 0.20 | 0.20 | |

| β25 | −1.20 | −1.18 | 0.13 | 0.13 | |

| β26 | −1.20 | −1.17 | 0.04 | 0.05 | |

| β27 | −1.20 | −1.20 | 0.12 | 0.12 | |

| β28 | −1.20 | −1.18 | 0.21 | 0.21 | |

| σε1 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| σε2 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| σε3 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| σε4 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| σc1 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| σc2 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| σc3 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| σc4 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |

| B1 | 1.20 | 1.19 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| B2 | 1.40 | 1.40 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| B3 | 1.30 | 1.29 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| B4 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| B12 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.04 | 0.03 | |

| B13 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| B14 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| B23 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| B24 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| B34 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

Note: Asymptotic standard error is the average of SE from 500 replicates. Empirical SE is standard error of estimates from 500 replications. γ, σε, σc, β, W2, B are as defined in section 2. B1 to B4 are the square roots of the diagonal elements of matrix B, and all other B parameters are correlation coefficients of the corresponding terms as indicated by numbers in the subscripts.

Table 2.

Average coverage probabilities of 95% confidence intervals for all parameters in a given model, and misclassification rates of simulation results.

| Number of classes | Average coverage (range) | Misclassification rate |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 94.89% (92.60%–98.80%) | 0.001% |

| 3 | 95.16% (92.80%–99.00%) | 2.29% |

| 4 | 95.61% (91.40%–99.80%) | 8.60% |

| 5 | 95.73% (93.00%–100.00%) | 12.29% |

| 6 | 96.15% (92.60%–100.00%) | 13.97% |

5. Application to the UDS data

The proposed multivariate finite mixture latent trajectory model was applied to examine longitudinal patterns of cognitive decline among dementia patients using data from the UDS in the NACC data repository. The UDS is an ongoing data collection that was implemented in 2005 at 34 past and present NIA-founded Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (ADC) around the country [19]. Patients were recruited into the ADCs and followed annually to collect information relevant to aging and dementia, including performance measures on neuropsychological tests in multiple cognitive domains such as memory and language [32, 33].

We used UDS Jan. 2014 data freeze. The sample in the analysis included Caucasian patients with any type of dementia who had at least four annual cognitive evaluations. We also restricted our analyses to those whose cognitive decline began after 60 years of age in order to exclude patients with early onset dementia. Tests from two cognitive domains were used: logical memory immediate and delayed recalls tests for the memory domain; Animal Fluency Test and the Boston Naming Test for the language domain. As indicated by Weintraub et al, age of onset, gender and education had significant effects on test scores and were included in both the class membership model and the latent trajectory model [33]. Final analysis data set included 30,004 observations from 1517 patients, of whom 52.74% were male with 15.07 mean years of education and 73.33 as mean age of onset. Since these four test scores have different ranges, all outcomes were rescaled to be between 0 and 10 to achieve computational efficiency. In addition, education (in number of years) and age of onset (in years) were rescaled to be between 0 and 1. The time variable, age, was measured by decades and centered on the mean age. We tested linear and quadratic trajectories with the assumed number of latent classes ranging from 2 to 6. We present the estimated log likelihood and BIC for all models in table 3.

Table 3.

Estimated log likelihoods and BICs in the UDS data for various models assuming different numbers of latent classes.

| Linear Trajectory | Quadratic Trajectory | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number of classes |

number of parameters |

Log Likelihood |

BIC | number of parameters |

Log Likelihood |

BIC |

| 2 | 43 | −47711.57 | 95738.10 | 47 | −47675.48 | 95695.22 |

| 3 | 58 | −47394.82 | 95214.45 | 64 | −47329.63 | 95128.02 |

| 4 | 73 | −46992.81 | 94520.31 | 81 | −46971.34 | 94535.97 |

| 5 | 88 | −46871.30 | 94387.15 | 98 | −46832.84 | 94383.48 |

| 6 | 103 | −46791.45 | 94337.31 | 115 | −46713.23 | 94268.78 |

Note: For the linear trajectory model with 2 classes, there are 4 parameters for Σε; 4 parameters for Σc; 10 parameters for covariance matrix of the first latent class B; 1 parameter for ; 4 parameters for γ2; 10 parameters for β1 and β2 respectively, leading to a total of 43 parameters. With each increasing number of classes, 1 parameter for ; 4 parameters for γg; 10 parameters for βg are added. For quadratic modesl, 2 quadratic parameters for memory and language domain are added for each βg.

It can be seen that the differences between linear and quadratic models are small relative to the complexity of the models. Therefore, we chose the linear model for its ease of interpretation. The decrease in BIC was more pronounced when the number of latent classes increased from 2 to 4, but the BIC values became relatively flat with 4 or more latent classes; thus, we chose the model with 4 latent classes as the final model following the recommended practice by several authors [12, 13, 15]. Parameters estimates in the multinomial model for latent class memberships and for the fixed effects in the latent trajectory models are presented in table 4.

Table 4.

Parameter estimates for the latent class memebership model and for the fixed effects in the latent trajactory model.

| Class 1 | Class 2 | Class 3 | Class 4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Models | Parameter | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE |

| Multinomial | |||||||||

| Intercept | 3.08 | 0.63 | 4.71 | 0.63 | 5.53 | 0.61 | 0 | Ref | |

| Sex | −0.20 | 0.28 | −0.63 | 0.28 | −0.20 | 0.32 | 0 | Ref | |

| Education | −1.65 | 0.99 | −3.99 | 0.97 | −5.98 | 0.80 | 0 | Ref | |

| Age of onset | −4.16 | 1.16 | −1.98 | 1.19 | −1.52 | 1.72 | 0 | Ref | |

| Trajectory | |||||||||

| Memory domain |

Intercept | −2.28 | 0.26 | −0.37 | 0.36 | −0.14 | 0.10 | −9.19 | 1.58 |

| Linear slope | −2.18 | 0.12 | −1.90 | 0.16 | −0.50 | 0.04 | −8.42 | 0.39 | |

| Sex | −0.08 | 0.08 | −0.29 | 0.17 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.39 | 0.85 | |

| Education | 0.19 | 0.34 | 1.40 | 0.40 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.34 | 1.93 | |

| Age of onset | 8.50 | 0.54 | 6.30 | 0.89 | 1.92 | 0.21 | 34.32 | 2.01 | |

| Language domain |

Intercept | −6.98 | 1.51 | 1.49 | 0.53 | 0.22 | 0.41 | −0.73 | 0.37 |

| Linear slope | −8.17 | 0.17 | −2.35 | 0.14 | −2.92 | 0.11 | −4.91 | 0.30 | |

| Sex | −0.26 | 0.33 | −0.38 | 0.16 | −0.35 | 0.14 | −0.40 | 0.54 | |

| Education | 0.31 | 1.87 | 2.28 | 0.66 | 2.25 | 0.57 | −1.47 | 1.02 | |

| Age of onset | 31.10 | 0.97 | 7.41 | 0.70 | 9.67 | 0.65 | 19.03 | 1.63 | |

Note: male is the reference for gender.

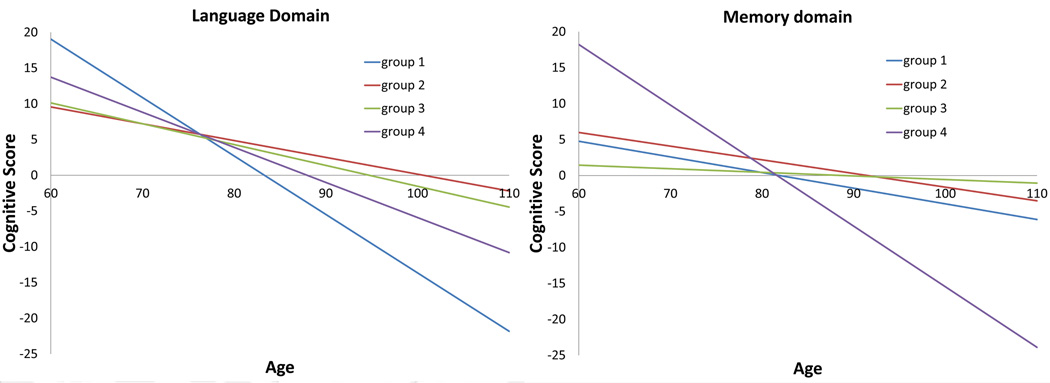

In figure 1, we present the predicted trajectories of male patients with 15 years of education and age of onset at 73 (chosen as the sample means) in four latent classes. Latent class 1 has the steepest decline in language but is relatively flat in memory decline; latent class 4 has the fastest decline in memory and also the second fastest decline in language; patients in latent classes 2 and 3 have less decline in both language and memory domains than those in latent classes 1 and 4.

Firgure 1.

Estimated trajectories of language (left) and memory (right) decline for male dementia patients with education and age of onset at the sample means in four latent classes.

We further examined the association between patient characteristics and the four identified latent classes and present the results in Table 5. Since APOE e4 allele is an important risk factor for AD and about 60% of AD patients carrys this allele [19, 34–37], we also included percentages of samples having it in each latent class. Latent classes 3 and 2 captured the majority of patients followed by latent class 1 and 4. More than 70% of the patients in latent classes 1 and 3 were clinically diagnosed as probable AD only as defined by NINCDS-ADRDA criteria [38, 39] and no any other form of dementia, while class 2 had the lowest percentage of probable AD only (41.37%) and the highest percentage of other demenitas. Patients in latent class 1 also had the highest percentage of being an APOE e4 carrier compared to patients in the other classes. For latent classes 2 and 4, about half of samples have other types of dementia and not surprisingly, less than half of samples have APOE e4 allele. However, just as there were differences between latent classes 1 and 3, latent classes 2 and 4 also differ in gender composition, years of education, and age of onset pointing to potentially different etiologies.

Table 5.

Patients characteristics by the four identified latent classes.

| class | number of patients |

male % |

Average years of Education (SD) |

Average age of onset (SD) |

APOE e4 carrier (%) |

Probable AD only (%) |

Other Dementia (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 300 | 54.00 | 15.91(2.89) | 70.66(6.56) | 72.69 | 76.00 | 22.67 |

| 2 | 510 | 59.80 | 15.18(3.30) | 73.35(7.21) | 44.57 | 41.37 | 55.88 |

| 3 | 560 | 46.96 | 14.16(3.24) | 74.03(6.88) | 57.79 | 71.96 | 27.14 |

| 4 | 147 | 47.62 | 16.38(2.10) | 76.06(9.00) | 47.06 | 51.02 | 42.86 |

To evaluate model fit, the average posterior probabilities for the linear model with 4 latent classes are presented in table 6. The diagonal values are all greater than 0.84, indicating a good separation of the four latent classes.

Table 6.

Average posterior probabilities of 4 latent classes identified

| Classified class |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.87 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.02 |

| 2 | 0.02 | 0.88 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| 3 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.84 | 0.00 |

| 4 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.89 |

6. Discussion

In this paper, we proposed a multivariate finite mixture latent trajectory model targeted to data that are often encountered in dementia studies. In these studies, there are multiple domains of cognitive performance, each of which may be measured by multiple neuropsychological tests. Our model is an extension of GBTM, GMM and the non-linear latent class model proposed by Proust-Lima et al, and can be used in studies where more than one test for the same underlying variable has been measured. We applied our method to the UDS data and identified four latent cognitive decline patterns.

Given that multiple cognitive measures are routinely collected in dementia and aging studies, appropriate statistical models with realistic assumptions for multiple tests in more than one domain are extremely important. The naïve method of analyzing data with multiple tests by modeling each test with a separate latent trajectory and without combining the information across different cognitive domains can lead to the spurious identification of many latent classes. There are some existing methods that attempt to reduce dimensionality by combining tests within the same domain using summed or weighted average test scores. However, as indicated by Gray and Brookmeyer, data reduction may cause loss of information and the results may be difficult to interpret [40]. In our method, by jointly modeling tests within the same domain, the number of model parameters is greatly reduced. By adding random test-specific effects, the differences and correlations among tests are accounted for. Furthermore, since these tests are often measurements of the same underlying latent construct, joint modeling can improve our ability to identify this construct.

The identified latent classes can be used for therapeutic and research purpose. Since patients in the same latent classes share similar cognitive decline patterns, this can help care providers and clinicians for better patients care and treatment. In addition, patients in each latent class may share the same disease etiology and may be caused by same genes; therefore the power in genetic studies that look for genes related dementia can be improved. For example, based on recent summary at ALzGene database, 695 genes related AD are found from 1395 studies, however, only a few of them are confirmed by multiple studies [34, 35]. The reason for this is, although patients are all clinically diagnosed as AD, their cognitive decline patterns differ dramatically and this heterogeneity makes results from a given study hard to replicate thus the ability to find true genes is greatly reduced. Our method can be used to find samples that have similar cognitive decline patterns and genetics studies from these phenotypically homogenous sub groups will be more comparable.

In our model, we assumed a normal distribution due to its tractability and ease of implementation. In our application, the distributions of logical memory immediate recall, Animal Fluency Test and the Boson Naming Test were approximately normal while logical memory delayed recall showed skewness to the right. However, the normal distribution assumption may not apply for tests that have categorical or binary responses. In the future, we will extend our work to model non-normal variables and/or mixed types of variables. Another limitation of using the normal assumption lies in selecting the number of classes using information-based criterion like BIC. It has been observed in this and many other studies that BIC always decreases as more classes are added [12, 20]. This problem is more pronounced when the sample size is large and sample sizes in each class are unbalanced. In these cases, the latent classes with larger sample sizes can be split into two or more latent classes [12] and currently the best way to address this problem is using external information to aid in model selection.

A common problem encountered in many dementia studies is floor or ceiling effects associated with some of the test scores. Proust et al proposed a transformation for the test scores using the cumulative beta distribution and demonstrated that the transformation fits the data well under these circumstances [17]. Jacqmin-Gadda et al have proposed a semi-parametric latent process model to address the particular problem of differential sensitivity of tests at different dementia stages [41]. In situations where a test consists of multiple items, an alternative approach is to model the distribution of individual item scores instead of the aggregated test score using the item response theory (IRT) [42–44]. This approach has the advantage of handling the floor and ceiling effect. However, it was designed to allow a single latent trajectory and additional research is needed to extend it to include multiple latent trajectories from more than one cognitive domain. Future research will be needed to generalize our models to increase their robustness given these additional challenges.

Acknowledgments

The work is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Grants R01 AG019181, and P30 AG10133.

The NACC database is funded by NIA/NIH Grant U01 AG016976. NACC data are contributed by the NIA-funded ADCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Steven Ferris, PhD), P30 AG013854 (PI M. Marsel Mesulam, MD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P50 AG016570 (PI David Teplow, PhD), P50 AG005131 (PI Douglas Galasko, MD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Montine, MD, PhD), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), and P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD).

Appendix

Mean parameter estimates, asymptotic standard error (SE) and empirical standard error from 500 replications in simulations for 2 to 6-class model

| A: 2-class model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | True Value |

Mean estimates |

Asymptotic SE |

Empirical SE |

|

| γ11 | 6.00 | 6.02 | 0.32 | 0.32 | |

| γ12 | −12.00 | −12.05 | 0.61 | 0.62 | |

| β11 | 5.60 | 5.58 | 0.13 | 0.13 | |

| β12 | 1.60 | 1.57 | 0.04 | 0.05 | |

| β13 | 1.60 | 1.60 | 0.12 | 0.12 | |

| β14 | 1.60 | 1.60 | 0.19 | 0.20 | |

| β15 | 1.20 | 1.18 | 0.13 | 0.14 | |

| β16 | 1.20 | 1.16 | 0.04 | 0.06 | |

| β17 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 0.13 | 0.13 | |

| β18 | 1.20 | 1.19 | 0.20 | 0.22 | |

| β21 | −5.60 | −5.58 | 0.13 | 0.13 | |

| β22 | −1.60 | −1.56 | 0.04 | 0.05 | |

| β23 | −1.60 | −1.60 | 0.12 | 0.12 | |

| β24 | −1.60 | −1.60 | 0.20 | 0.20 | |

| β25 | −1.20 | −1.18 | 0.13 | 0.13 | |

| β26 | −1.20 | −1.17 | 0.04 | 0.05 | |

| β27 | −1.20 | −1.20 | 0.12 | 0.12 | |

| β28 | −1.20 | −1.18 | 0.21 | 0.21 | |

| σε1 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| σε2 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| σε3 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| σε4 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| σc1 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| σc2 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| σc3 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| σc4 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |

| B1 | 1.20 | 1.19 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| B2 | 1.40 | 1.40 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| B3 | 1.30 | 1.29 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| B4 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| B12 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.04 | 0.03 | |

| B13 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| B14 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| B23 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| B24 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| B34 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.05 | 0.05 | ||

| B: 3-class model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | True Value |

Mean estimates |

Asymptotic SE |

Empirical SE |

|

| γ11 | 11.00 | 11.05 | 0.68 | 0.69 | |

| γ12 | −14.00 | −14.13 | 0.74 | 0.72 | |

| γ21 | 7.00 | 6.99 | 0.69 | 0.70 | |

| γ22 | −7.00 | −6.99 | 0.63 | 0.63 | |

| β11 | 5.60 | 5.57 | 0.13 | 0.14 | |

| β12 | 1.60 | 1.57 | 0.04 | 0.06 | |

| β13 | 1.60 | 1.60 | 0.13 | 0.13 | |

| β14 | 1.60 | 1.60 | 0.22 | 0.22 | |

| β15 | 1.20 | 1.17 | 0.15 | 0.15 | |

| β16 | 1.20 | 1.16 | 0.04 | 0.07 | |

| β17 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 0.13 | 0.14 | |

| β18 | 1.20 | 1.22 | 0.24 | 0.24 | |

| β21 | −5.60 | −5.57 | 0.14 | 0.15 | |

| β22 | −1.60 | −1.57 | 0.05 | 0.06 | |

| β23 | −1.60 | −1.60 | 0.14 | 0.14 | |

| β24 | −1.60 | −1.62 | 0.23 | 0.24 | |

| β25 | −1.20 | −1.17 | 0.16 | 0.16 | |

| β26 | −1.20 | −1.17 | 0.05 | 0.07 | |

| β27 | −1.20 | −1.20 | 0.14 | 0.15 | |

| β28 | −1.20 | −1.19 | 0.26 | 0.25 | |

| β31 | 6.00 | 5.98 | 0.15 | 0.15 | |

| β32 | 2.00 | 1.97 | 0.05 | 0.06 | |

| β33 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.14 | 0.13 | |

| β34 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.25 | 0.23 | |

| β35 | 1.60 | 1.58 | 0.15 | 0.15 | |

| β36 | 1.60 | 1.57 | 0.05 | 0.06 | |

| β37 | 1.60 | 1.59 | 0.15 | 0.14 | |

| β38 | 1.60 | 1.61 | 0.24 | 0.24 | |

| σε1 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |

| σε2 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| σε3 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.02 | 0.01 | |

| σε4 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| σc1 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| σc2 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| σc3 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| σc4 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| B1 | 1.20 | 1.19 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| B2 | 1.40 | 1.40 | 0.03 | 0.04 | |

| B3 | 1.30 | 1.29 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| B4 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| B12 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| B13 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| B14 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| B23 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| B24 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.03 | |

| B34 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.05 | 0.05 | ||

| 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.05 | 0.05 | ||

| C: 4-class model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | True Value |

Mean estimates |

Asymptotic SE |

Empirical SE |

|

| γ11 | 15.00 | 15.16 | 1.48 | 1.60 | |

| γ12 | −14.00 | −14.17 | 1.10 | 1.19 | |

| γ21 | 12.00 | 12.15 | 1.46 | 1.58 | |

| γ22 | −9.00 | −9.13 | 1.03 | 1.12 | |

| γ31 | 8.00 | 8.04 | 1.24 | 1.36 | |

| γ32 | −6.00 | −6.03 | 0.79 | 0.88 | |

| β11 | 5.60 | 5.60 | 0.16 | 0.17 | |

| β12 | 1.60 | 1.60 | 0.04 | 0.07 | |

| β13 | 1.60 | 1.60 | 0.15 | 0.15 | |

| β14 | 1.60 | 1.60 | 0.26 | 0.26 | |

| β15 | 1.50 | 1.49 | 0.17 | 0.18 | |

| β16 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 0.04 | 0.08 | |

| β17 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 0.16 | 0.16 | |

| β18 | 1.50 | 1.51 | 0.27 | 0.28 | |

| β21 | 7.60 | 7.60 | 0.16 | 0.17 | |

| β22 | −1.60 | −1.60 | 0.04 | 0.07 | |

| β23 | −1.60 | −1.60 | 0.15 | 0.15 | |

| β24 | −1.60 | −1.60 | 0.24 | 0.26 | |

| β25 | −1.50 | −1.51 | 0.17 | 0.18 | |

| β26 | −1.50 | −1.50 | 0.04 | 0.08 | |

| β27 | −1.50 | −1.50 | 0.17 | 0.16 | |

| β28 | −1.50 | −1.49 | 0.28 | 0.28 | |

| β31 | 4.00 | 3.99 | 0.27 | 0.27 | |

| β32 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 0.06 | 0.11 | |

| β33 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 0.23 | 0.24 | |

| β34 | 1.20 | 1.22 | 0.42 | 0.42 | |

| β35 | 1.10 | 1.11 | 0.28 | 0.29 | |

| β36 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 0.06 | 0.12 | |

| β37 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 0.27 | 0.26 | |

| β38 | 1.10 | 1.09 | 0.45 | 0.46 | |

| β41 | 6.00 | 6.00 | 0.16 | 0.16 | |

| β42 | −1.20 | −1.20 | 0.04 | 0.06 | |

| β43 | −1.20 | −1.19 | 0.15 | 0.15 | |

| β44 | −1.20 | −1.20 | 0.25 | 0.25 | |

| β45 | −1.10 | −1.10 | 0.17 | 0.17 | |

| β46 | −1.10 | −1.10 | 0.04 | 0.06 | |

| β47 | −1.10 | −1.10 | 0.15 | 0.16 | |

| β48 | −1.10 | −1.12 | 0.27 | 0.27 | |

| σε1 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |

| σε2 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| σε3 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |

| σε4 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| σc1 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| σc2 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| σc3 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| σc4 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| B1 | 1.20 | 1.19 | 0.05 | 0.06 | |

| B2 | 1.40 | 1.40 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| B3 | 1.30 | 1.29 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |

| B4 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 0.05 | 0.04 | |

| B12 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| B13 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| B14 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |

| B23 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| B24 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| B34 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.07 | 0.06 | ||

| 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.08 | 0.08 | ||

| 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.05 | 0.04 | ||

| D: 5-class model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | True Value |

Mean estimates |

Asymptotic SE |

Empirical SE |

|

| γ11 | 20.00 | 20.38 | 1.67 | 1.77 | |

| γ12 | −15.00 | −15.28 | 1.23 | 1.31 | |

| γ21 | 17.00 | 17.35 | 1.62 | 1.73 | |

| γ22 | −11.00 | −11.23 | 1.12 | 1.19 | |

| γ31 | 14.00 | 14.26 | 1.35 | 1.42 | |

| γ32 | −8.00 | −8.15 | 0.74 | 0.77 | |

| γ41 | 10.00 | 10.14 | 1.10 | 1.18 | |

| γ42 | −5.00 | −5.07 | 0.54 | 0.58 | |

| β11 | 5.60 | 5.61 | 0.18 | 0.19 | |

| β12 | 1.60 | 1.60 | 0.05 | 0.08 | |

| β13 | 1.60 | 1.60 | 0.17 | 0.17 | |

| β14 | 1.60 | 1.60 | 0.28 | 0.28 | |

| β15 | 1.50 | 1.51 | 0.18 | 0.19 | |

| β16 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 0.05 | 0.08 | |

| β17 | 1.50 | 1.51 | 0.18 | 0.18 | |

| β18 | 1.50 | 1.48 | 0.31 | 0.30 | |

| β21 | 7.60 | 7.60 | 0.26 | 0.26 | |

| β22 | −1.60 | −1.60 | 0.06 | 0.11 | |

| β23 | −1.60 | −1.61 | 0.25 | 0.23 | |

| β24 | −1.60 | −1.60 | 0.39 | 0.41 | |

| β25 | −1.50 | −1.51 | 0.27 | 0.27 | |

| β26 | −1.50 | −1.50 | 0.06 | 0.12 | |

| β27 | −1.50 | −1.49 | 0.25 | 0.25 | |

| β28 | −1.50 | −1.49 | 0.45 | 0.44 | |

| β31 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 0.23 | 0.25 | |

| β32 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 0.06 | 0.10 | |

| β33 | 1.20 | 1.21 | 0.22 | 0.22 | |

| β34 | 1.20 | 1.18 | 0.37 | 0.38 | |

| β35 | 1.10 | 1.09 | 0.26 | 0.27 | |

| β36 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 0.06 | 0.11 | |

| β37 | 1.10 | 1.09 | 0.25 | 0.24 | |

| β38 | 1.10 | 1.13 | 0.40 | 0.42 | |

| β41 | 6.00 | 6.02 | 0.19 | 0.20 | |

| β42 | −1.20 | −1.20 | 0.05 | 0.08 | |

| β43 | −1.20 | −1.19 | 0.18 | 0.18 | |

| β44 | −1.20 | −1.23 | 0.30 | 0.30 | |

| β45 | −1.10 | −1.09 | 0.19 | 0.20 | |

| β46 | −1.10 | −1.10 | 0.05 | 0.08 | |

| β47 | −1.10 | −1.10 | 0.19 | 0.19 | |

| β48 | −1.10 | −1.12 | 0.32 | 0.32 | |

| β51 | 3.00 | 3.01 | 0.21 | 0.22 | |

| β52 | 1.40 | 1.40 | 0.05 | 0.11 | |

| β53 | 1.40 | 1.40 | 0.20 | 0.20 | |

| β54 | 1.40 | 1.39 | 0.34 | 0.34 | |

| β55 | −1.30 | −1.29 | 0.22 | 0.23 | |

| β56 | −1.30 | −1.30 | 0.05 | 0.10 | |

| β57 | −1.30 | −1.31 | 0.22 | 0.21 | |

| β58 | −1.30 | −1.30 | 0.37 | 0.36 | |

| σε1 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |

| σε2 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| σε3 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |

| σε4 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| σc1 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| σc2 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| σc3 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| σc4 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| B1 | 1.20 | 1.19 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |

| B2 | 1.40 | 1.40 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| B3 | 1.30 | 1.29 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |

| B4 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| B12 | 0.65 | 0.66 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| B13 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| B14 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |

| B23 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| B24 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| B34 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.08 | 0.08 | ||

| 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.08 | 0.08 | ||

| 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.05 | 0.05 | ||

| 1.10 | 1.10 | 0.09 | 0.09 | ||

| E: 6-class model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | True Value |

Mean estimates |

Asymptotic SE |

Empirical SE |

|

| γ11 | 21.00 | 21.31 | 1.60 | 1.85 | |

| γ12 | −14.00 | −14.26 | 1.04 | 1.12 | |

| γ21 | 20.00 | 20.28 | 1.56 | 1.83 | |

| γ22 | −10.00 | −10.18 | 0.81 | 0.93 | |

| γ31 | 17.00 | 17.21 | 1.47 | 1.72 | |

| γ32 | −8.00 | −8.11 | 0.67 | 0.78 | |

| γ41 | 14.00 | 14.17 | 1.43 | 1.63 | |

| γ42 | −6.00 | −6.07 | 0.59 | 0.68 | |

| γ51 | 10.00 | 10.11 | 1.31 | 1.37 | |

| γ52 | −4.00 | −4.04 | 0.51 | 0.53 | |

| β11 | 5.60 | 5.61 | 0.31 | 0.32 | |

| β12 | 1.60 | 1.60 | 0.07 | 0.13 | |

| β13 | 1.60 | 1.58 | 0.29 | 0.28 | |

| β14 | 1.60 | 1.60 | 0.49 | 0.50 | |

| β15 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 0.31 | 0.34 | |

| β16 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 0.08 | 0.14 | |

| β17 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 0.30 | 0.30 | |

| β18 | 1.50 | 1.49 | 0.51 | 0.55 | |

| β21 | 7.60 | 7.60 | 0.17 | 0.18 | |

| β22 | −1.60 | −1.61 | 0.05 | 0.07 | |

| β23 | −1.60 | −1.60 | 0.15 | 0.16 | |

| β24 | −1.60 | −1.59 | 0.26 | 0.27 | |

| β25 | −1.50 | −1.51 | 0.17 | 0.18 | |

| β26 | −1.50 | −1.50 | 0.05 | 0.08 | |

| β27 | −1.50 | −1.50 | 0.18 | 0.17 | |

| β28 | −1.50 | −1.49 | 0.28 | 0.29 | |

| β31 | 4.00 | 3.99 | 0.26 | 0.30 | |

| β32 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 0.06 | 0.12 | |

| β33 | 1.20 | 1.19 | 0.24 | 0.25 | |

| β34 | 1.20 | 1.21 | 0.42 | 0.46 | |

| β35 | 1.10 | 1.09 | 0.29 | 0.33 | |

| β36 | 1.10 | 1.09 | 0.07 | 0.13 | |

| β37 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 0.27 | 0.27 | |

| β38 | 1.10 | 1.11 | 0.48 | 0.52 | |

| β41 | 6.00 | 6.03 | 0.29 | 0.32 | |

| β42 | −1.20 | −1.20 | 0.07 | 0.12 | |

| β43 | −1.20 | −1.20 | 0.26 | 0.27 | |

| β44 | −1.20 | −1.23 | 0.45 | 0.49 | |

| β45 | −1.10 | −1.08 | 0.28 | 0.32 | |

| β46 | −1.10 | −1.10 | 0.06 | 0.12 | |

| β47 | −1.10 | −1.10 | 0.28 | 0.29 | |

| β48 | −1.10 | −1.13 | 0.46 | 0.54 | |

| β51 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 0.24 | 0.25 | |

| β52 | 1.40 | 1.40 | 0.06 | 0.13 | |

| β53 | 1.40 | 1.41 | 0.22 | 0.23 | |

| β54 | 1.40 | 1.39 | 0.39 | 0.40 | |

| β55 | −1.30 | −1.31 | 0.25 | 0.28 | |

| β56 | −1.30 | −1.30 | 0.07 | 0.12 | |

| β57 | −1.30 | −1.30 | 0.25 | 0.25 | |

| β58 | −1.30 | −1.30 | 0.42 | 0.45 | |

| β61 | 6.00 | 6.01 | 0.24 | 0.24 | |

| β62 | −1.40 | −1.40 | 0.06 | 0.11 | |

| β63 | −1.40 | −1.40 | 0.22 | 0.22 | |

| β64 | −1.40 | −1.41 | 0.37 | 0.38 | |

| β65 | 1.30 | 1.29 | 0.25 | 0.27 | |

| β66 | 1.30 | 1.30 | 0.06 | 0.12 | |

| β67 | 1.30 | 1.31 | 0.24 | 0.24 | |

| β68 | 1.30 | 1.30 | 0.42 | 0.42 | |

| σε1 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |

| σε2 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| σε3 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |

| σε4 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| σc1 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| σc2 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| σc3 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| σc4 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.06 | 0.05 | |

| B1 | 1.20 | 1.18 | 0.07 | 0.07 | |

| B2 | 1.40 | 1.39 | 0.07 | 0.07 | |

| B3 | 1.30 | 1.28 | 0.08 | 0.08 | |

| B4 | 1.50 | 1.49 | 0.07 | 0.07 | |

| B12 | 0.65 | 0.66 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| B13 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| B14 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |

| B23 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| B24 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| B34 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.10 | 0.10 | ||

| 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.11 | 0.11 | ||

| 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.09 | 0.09 | ||

| 1.10 | 1.12 | 0.12 | 0.13 | ||

| 1.05 | 1.06 | 0.12 | 0.12 | ||

Note: Asymptotic standard error is the average of SE from 500 replications; Empirical SE is standard error of estimates from 500 replications; γ, σε, σc, β, W2, B are defined in section 2; B1 to B4 are the square roots of the diagonal elements of matrix B, and all other B parameters are correlation coefficients of the corresponding terms as indicated by numbers in the subscripts.

References

- 1.Salmon DP, Bondi MW. Neuropsychological assessment of dementia. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:257–282. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayden KM, et al. Cognitive decline in the elderly: an analysis of population heterogeneity. Age Ageing. 2011;40(6):684–689. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afr101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galton CJ, et al. Atypical and typical presentations of Alzheimer's disease: a clinical, neuropsychological, neuroimaging and pathological study of 13 cases. Brain. 2000;123(Pt 3):484–498. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.3.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin A, et al. Towards a behavioral typology of Alzheimer's patients. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1986;8(5):594–610. doi: 10.1080/01688638608405178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neary D, et al. Neuropsychological syndromes in presenile dementia due to cerebral atrophy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1986;49(2):163–174. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.49.2.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller BL, et al. Frontal lobe degeneration: clinical, neuropsychological, and SPECT characteristics. Neurology. 1991;41(9):1374–1382. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.9.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neary D, Snowden J, Mann D. Frontotemporal dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4(11):771–780. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neary D, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51(6):1546–1554. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neary D, et al. Dementia of frontal lobe type. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1988;51(3):353–361. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.51.3.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perry RJ, Hodges JR. Differentiating frontal and temporal variant frontotemporal dementia from Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 2000;54(12):2277–2284. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.12.2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagin DS. Analyzing developmental trajectories: A semiparametric, group-based approach. Psychol Methods. 1999;4:139–157. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagin DS. Group-based modeling of development. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagin DS, Odgers CL. Group-based trajectory modeling in clinical research. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:109–138. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muthen B. Beyond SEM: General latent variable modeling. Behaviormetrika. 2002;29:81–117. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muthen B. Latent variable analysis: growth mixture modeling and related techniques for longitudinal data. In: Kaplan D, editor. The Sage Handbook of Quantitative Methodology for the Social Sciences. Newbury Park, CA: 2004. pp. 345–368. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muthen B, Shedden K. Finite mixture modeling with mixture outcomes using the EM algorithm. Biometrics. 1999;55:463–469. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Proust C, et al. A nonlinear model with latent process for cognitive evolution using multivariate longitudinal data. Biometrics. 2006;62(4):1014–1024. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2006.00573.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Proust-Lima C, Letenneur L, Jacqmin-Gadda H. A nonlinear latent class model for joint analysis of multivariate longitudinal data and a binary outcome. Statistics in Medicine. 2007;26:2229–2245. doi: 10.1002/sim.2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center. Available from: https://www.alz.washington.edu/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.McLachlan GJ, Peel D. Finite Mixture Models. New York: Wiley-Intersci; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McLachlan GJ, Krishnan T. The EM Algorithm and Extensions. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ng SK, et al. A mixture model with random-effects components for clustering correlated gene-expression profiles. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(14):1745–1752. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB. Maximum Likelihood from Incomplete Data via the EM Algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1977;39(1):1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Figueiredo MA. Lecture notes on bayesian estimation and classification. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altman NS. An Introduction to Kernel and Nearest-Neighbor Nonparametric Regression. American Statistician. 1992;46(3):175–185. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodman LA. On the Assignment of Individuals to Latent Classes. Sociological Methodology. 2007;37:1–22. 2007. 37. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muthen B, et al. General growth mixture modeling for randomized preventive interventions. Biostatistics. 2002;3(4):459–475. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/3.4.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwartz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann. Stat. 1978;(6):461–464. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthen BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct. Equ. Model. 2007;14:535–569. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tofighi D, Enders CK. Identifying the correct number of classes in growth mixture models. Advances in Latent Variable Mixture Models. 2008:317–341. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang C-C. Evaluating latent class analysis models in qualitative phenotype identification. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis. 2006;50(4):1090–1104. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morris JC, et al. The Uniform Data Set (UDS): clinical and cognitive variables and descriptive data from Alzheimer Disease Centers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20(4):210–216. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000213865.09806.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weintraub S, et al. The Alzheimer's Disease Centers' Uniform Data Set (UDS): the neuropsychologic test battery. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23(2):91–101. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318191c7dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alzheimer's Disease Genetics Consortium. Available from: https://alois.med.upenn.edu/adgc/about/overview.html. [Google Scholar]

- 35.The AlzGene database. Available from: http://www.alzgene.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 36.Corder EH, et al. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer's disease in late onset families. Science. 1993;261(5123):921–923. doi: 10.1126/science.8346443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strittmatter WJ, et al. Apolipoprotein E high-avidity binding to beta-amyloid and increased frequency of type 4 allele in late-onset familial Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(5):1977–1981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McKhann G, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McKhann GM, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gray SM, Brookmeyer R. Estimating a treatment effect from multidimensional longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1998;54(3):976–988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jacqmin-Gadda H, Proust-Lima C, Amieva H. Semi-parametric latent process model for longitudinal ordinal data: Application to cognitive decline. Statistics in Medicine. 2010;29(26):2723–2731. doi: 10.1002/sim.4035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fox JP. Bayesian Item Response Modeling: Theory and Applications. Bayesian Item Response Modeling: Theory and Applications. 2010:1–313. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klein Entink RH, Fox JP, van den Hout A. A mixture model for the joint analysis of latent developmental trajectories and survival. Stat Med. 2011;30(18):2310–2325. doi: 10.1002/sim.4266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van den Hout A, Fox JP, Muniz-Terrera G. Longitudinal mixed-effects models for latent cognitive function. Statistical Modelling. 2015;15(4):366–387. [Google Scholar]