Abstract

Objectives

To identify the risk factors for and adverse newborn outcomes associated with maternal deaths from direct and indirect causes in the UK.

Design

Unmatched case–control analysis.

Setting

All hospitals caring for pregnant women in the UK.

Population

Comprised 383 women who died (cases) from direct or indirect causes from 2009 to 2013 (Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths in the UK) and 1516 women who did not have any life‐threatening complications during pregnancy and childbirth (controls) obtained from UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS).

Methods

Multivariable regression analyses were undertaken to examine potential risk factors, their incremental effects, and adverse newborn outcomes associated with maternal deaths.

Outcomes

Odds ratios associated for risk factors for maternal death and newborn outcomes (stillbirth, admission to neonatal intensive care unit [NICU], early neonatal death) and incremental risk.

Results

Seven factors, of 13 examined, were independently associated with increased odds of maternal death: pre‐existing medical comorbidities (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 8.65; 95% CI 6.29–11.90), anaemia during pregnancy (aOR 3.58; 95% CI 1.14–11.21), previous pregnancy problems (aOR 1.85; 95% CI 1.33–2.57), inadequate use of antenatal care (aOR 46.85; 95% CI 19.61–111.94), substance misuse (aOR 12.21; 95% CI 2.33–63.98), unemployment (aOR 1.81; 95% CI 1.08–3.04) and maternal age (aOR 1.06; 95% CI 1.04–1.09). There was a four‐fold increase in the odds of death per unit increase in the number of risk factors. Odds of stillbirth, admission to NICU and early neonatal death were higher among women who died.

Conclusion

This study reiterates the need for optimal care for women with medical comorbidities and older age, and the importance of adequate antenatal care. It demonstrates the existence of socio‐economic inequalities in maternal death in the UK.

Tweetable abstract

Medical comorbidities and socio‐economic inequalities are important risk factors for maternal death in the UK.

Keywords: Early neonatal death, maternal death, risk factors, stillbirth, UK

Tweetable abstract

Medical comorbidities and socio‐economic inequalities are important risk factors for maternal death in the UK.

Introduction

Previous studies have shown that medical comorbidities, inadequate use of antenatal care, hypertensive disorders during current pregnancy, previous pregnancy problems, obesity and sociodemographic factors such as older maternal age (>35 years), belonging to unemployed or manual socio‐economic groups, substance misuse and being from minority ethnic groups were independently associated with increased risk of progression from severe pregnancy complications to death among pregnant women in the UK.1, 2 However, women who suffer severe complications may be different from the majority of women, who have an uncomplicated pregnancy and childbirth, and it is therefore important to examine whether women who die during pregnancy or childbirth differ from the normal pregnant population. Identifying these differences could help to update the existing pregnancy care pathways recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)3 to improve management of the risk factors to prevent complications and death during pregnancy and childbirth in the UK.

Furthermore, the health of the mother and care during pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period are strong determinants of fetal and neonatal wellbeing. Studies mainly from low‐ and middle‐income countries show that maternal death is associated with increased risk of stillbirth and infant death.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 In the UK, 3286 babies were stillborn9 and a total of 2966 infants died10, 11, 12 in 2013. However, the association of stillbirth and newborn death with maternal mortality in the UK is not clearly understood from the available published literature. The objectives of our study were to identify the risk factors for and any adverse fetal and newborn outcomes associated with maternal deaths from direct and indirect causes in the UK in 2009–13.

Methods

We conducted an unmatched case–control analysis using data from two sources. Cases were 383 women who died from direct (obstetric causes) or indirect (pre‐existing medical conditions aggravated by the physiological effects of pregnancy) causes during pregnancy or within 42 days of the end of pregnancy regardless of how the pregnancy ended (miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, termination or birth) from 2009 to 2013 in the UK. Information on maternal deaths was extracted from the surveillance database of the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths.13, 14 Population controls were obtained from the UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS)15 from three studies conducted between 2010 and 2012. These were 1516 women who did not have any severe life‐threatening complications during pregnancy and childbirth (referred to henceforth as women who had an uncomplicated pregnancy).

Details of the MBRRACE‐UK13, 14 and UKOSS15, 16 methodologies have been described elsewhere. The MBRRACE‐UK collaboration conducts surveillance of maternal deaths in the UK. Deaths of women during or after pregnancy are notified to the MBRRACE‐UK office directly from the hospital in which the death occurred. Deaths are also identified from a number of other sources including Coroners/Procurators Fiscal, pathologists, Local Supervising Authority Midwifery Officers, and inquest reports from the media. Case‐ascertainment is also verified with routine birth and death vital statistics records from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) for England and Wales, National Records of Scotland (NRS)14 and Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA).17 UKOSS is a research platform that was established in 2005 to conduct population‐based studies of the aetiology, management and outcomes of uncommon disorders of pregnancy.15 This rolling programme is maintained through case notification cards sent to all consultant‐led obstetric units in the UK every month with an approach of ‘nil‐reporting’. For every case reported, details are collected for the case and one or more controls (women who delivered immediately before the cases in the same hospital) on data collection forms by the clinician responsible for managing the case.15, 16 Over a period of 10 years UKOSS has accrued detailed national data on women with severe complications during pregnancy and childbirth as well as detailed information on women who had an uncomplicated pregnancy and childbirth (control groups).

We examined the association with maternal death of 13 potential risk factors for maternal mortality and morbidity18, 19, 20, 21, 22 for which comparable information was available from the two sources (MBRRACE‐UK and UKOSS): gestational diabetes, anaemia during current pregnancy, multiple pregnancy, inadequate use of antenatal care services, smoking, substance misuse, previous pregnancy problems, pre‐existing medical conditions, parity, body mass index (BMI), employment status, maternal age and ethnicity. Women were categorised into different ethnic groups according to the UK national census classification.23 Women who concealed pregnancy, were booked late for antenatal care (after 12 completed weeks of gestation) or did not receive minimal antenatal care were categorised as women who did not receive adequate antenatal care and these factors were used to generate a binary variable ‘inadequate use of antenatal care services’.21 We did not categorise women who died in early pregnancy as having ‘inadequate antenatal care’. Based on the number of pregnancies beyond 24 weeks, women were grouped as nulliparous, multiparous (one to four pregnancies) and grand‐multiparous (five or more pregnancies). Data on employment status of the women or their partners (where information about employment status of the women was not available) was used to generate a binary variable of employed or unemployed as a proxy for socio‐economic status. Women who were reported to have suffered from any pregnancy‐related problems in a previous pregnancy such as thrombotic events, placental problems, haemorrhage, pre‐eclampsia, eclampsia, puerperal psychosis were grouped as having suffered a previous pregnancy problem.

We tested the continuous variables, maternal age and BMI, for deviations from linearity by fitting functional polynomials in the univariable logistic regression models with multiple transformations of the continuous variable.24 Results showed that maternal age had a linear association with the outcome, but BMI did not, hence BMI was categorised into four groups—normal (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2) and obese (≥30 kg/m2).25 As was done in a previous study,2 medical comorbidities were grouped initially as a single variable, and subsequently into 16 clinically meaningful subgroups to explore any specific drivers of any association: asthma, autoimmune diseases, inflammatory disorders and allergic/atopic conditions (excluding asthma, example eczema and ulcerative colitis), cardiac disease (congenital or acquired), diabetes mellitus, endocrine disorders (other than diabetes mellitus), epilepsy, haematological disorders, essential hypertension, blood‐borne viruses, infection (other than blood‐borne viruses, example sexually transmitted infections, tuberculosis, and group B streptococcus infection), neurological disorders, musculoskeletal disorders, mental health problems, renal problems and thrombotic event.

In addition, we examined the association of maternal death with three adverse newborn outcomes—stillbirth, admission to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and early neonatal death based on clinician‐reported information on the data collection form for UKOSS and surveillance form for maternal deaths.

Study power

The fixed sample size of 383 cases (women who died) and 1516 controls (women with normal pregnancy) included in this analysis provided 80% power to detect an odds ratio of 1.34 or greater associated with maternal death at P < 0.05 (two‐tailed) for the risk factor that had the highest prevalence among the controls (55% for multiparity) and an odds ratio of 8.6 or greater for substance misuse, which had the lowest prevalence (0.1%).

Statistical analysis

We conducted an initial descriptive analysis of the cases and controls to examine the crude associations between each of the 13 independent variables and the outcome. A core logistic regression model (model‐1) was built including 12 variables (except parity) that were identified from previous literature to be associated with maternal death. Tests for correlation between the independent variables showed that parity and previous pregnancy problems were moderately correlated (r = 0.40, P < 0.001); hence, parity was not included in the multivariable model. We did not find any other significant moderate to strong correlations among the variables. We included maternal age as a continuous variable in the multivariable regression analysis and also tested an ordered categorical variable in a separate model to understand whether the risk of dying was higher in certain age groups. This did not materially change the adjusted odds ratios for other variables included in the analysis.

We analysed the odds of three adverse newborn outcomes (stillbirth, admission to NICU and early neonatal death) among women who died compared with the comparison pregnant women by conducting exact logistic regression analyses for each of these adverse events separately in models 2, 3 and 4. All pre‐existing medical conditions were found to be significantly associated with maternal death at P < 0.05 using univariable analyses, hence all 16 variables were included in a multivariable model (model‐5).

We tested for plausible interactions by fitting interaction terms into the multivariable model‐1 followed by likelihood ratio testing (LR‐test). No significant interactions were identified. Missing information was <1% for seven variables, but higher for BMI, employment status, smoking, previous pregnancy problems, and anaemia and gestational diabetes during current pregnancy. Data were not assumed to be missing at random based on the findings of previous studies21, 26 and a proxy variable was generated by categorising the missing data as a separate group for each variable. Sensitivity analysis was conducted for variables with >1% missing information by redistributing the missing observations into the different categories of the variables.

Employing the method used in a previous study,2 we generated a risk factor score by assigning a score of one to each factor found to be significantly associated with increased odds of maternal death in the multivariable logistic regression analysis. This was used to estimate the incremental odds of maternal mortality in the UK associated with the presence of one or more risk factors. We calculated the population attributable fraction for the ‘risk factors’ score and the individual factors using standard methods for calculating population attributable fraction in case–control studies.27 All analyses were performed using stata version 13.1, SE (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Multivariable logistic regression analysis (model 1) identified seven factors that were independently associated with increased odds of maternal death in the UK (Table 1), and that explained 36% of the variance in the outcome. The odds of maternal death (from direct or indirect causes) in the UK was almost nine‐fold higher among women who had a pre‐existing medical condition compared with women who did not (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 8.65; 95% CI 6.29–11.90) and was more than three and a half times higher among women who had anaemia during their current pregnancy (aOR 3.58; 95% CI 1.14–11.21). Inadequate use of antenatal care (aOR 46.85; 95% CI 19.61–111.94) and previous pregnancy problems (aOR 1.85; 95% CI 1.33–2.57) were significantly associated with higher odds of maternal death. Women who were known substance misusers had more than 12 times the odds of death (aOR 12.21; 95% CI 2.33–63.98) and being unemployed was associated with almost twice the odds of death (aOR 1.81; 95% CI 1.08–3.04). The odds of maternal death increased linearly by 6% per year increase in maternal age (Table 1) after adjusting for the other risk factors for maternal death.

Table 1.

Factors associated with direct and indirect maternal deaths in the UK in 2009–13 (Model‐1a)

| Risk factors | No. of cases (%) n = 383 | No. of controls (%) n = 1516 | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy related factors | ||||

| Parity | ||||

| Nulliparous | 132 (34.4) | 652 (43.0) | 1 (Ref) | g |

| Multiparous | 222 (58.0) | 839 (55.3) | 1.31 (1.03–1.66) | |

| Grand‐multiparous | 21 (5.5) | 25 (1.7) | 4.15 (2.26–7.63) | |

| Missing | 8 (2.1) | 0 (0) | ||

| Multiple pregnancy during current pregnancy | ||||

| No | 365 (95.3) | 1495 (98.6) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Yes | 10 (2.6) | 21 (1.4) | 1.95 (0.91–4.18) | 1.96 (0.71–5.38) |

| Missing | 8 (2.1) | 0 (0) | Omitted | Omitted |

| Gestational diabetes during current pregnancy | ||||

| No | 327 (85.4) | 1471 (97.0) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Yes | 20 (5.2) | 39 (2.6) | 2.31 (1.33–4.01) | 1.30 (0.62–2.73) |

| Missing | 36 (9.4) | 6 (0.4) | 27.0 (11.28–64.59) | Omitted |

| Anaemia during current pregnancy | ||||

| No | 336 (87.7) | 1498 (98.8) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Yes | 11 (2.9) | 12 (0.8) | 4.09 (1.79–9.34) | 3.58 (1.14–11.21) |

| Missing | 36 (9.4) | 6 (0.4) | 26.75 (11.18–64.00) | Omitted |

| Inadequate use of antenatal carec | ||||

| No | 276 (72.1) | 1503 (99.1) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Yes | 106 (27.7) | 7 (0.5) | 82.46 (37.97–179.09) | 46.85 (19.61–111.94) |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) | 6 (0.4) | 0.91 (0.11–7.57) | Omitted |

| Previous pregnancy problemse | ||||

| No | 213 (55.6) | 1244 (82.1) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Yes | 150 (39.2) | 268 (17.7) | 3.27 (2.55–4.19) | 1.85 (1.33–2.57) |

| Missing | 20 (5.2) | 4 (0.3) | 29.20 (9.88–86.27) | 0.91 (0.09–9.76) |

| Pre‐existing medical problemsf | ||||

| No | 91 (23.8) | 1189 (78.4) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Yes | 278 (72.6) | 324 (21.4) | 11.21 (8.59–14.64) | 8.65 (6.29–11.90) |

| Missing | 14 (3.6) | 3 (0.2) | 60.97 (17.21–216.05) | 12.51 (1.80–86.85) |

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) | ||||

| <18.5 | 9 (2.4) | 27 (1.8) | 1.63 (0.75–3.54) | 2.08 (0.80–5.44) |

| 18.5–24 | 147 (38.4) | 719 (47.4) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| 25–29 | 83 (21.7) | 403 (26.6) | 1.01 (0.75–1.35) | 0.83 (0.56–1.22) |

| ≥30 | 107 (27.9) | 323 (21.3) | 1.62 (1.22–2.15) | 1.14 (0.78–1.68) |

| Missing | 37 (9.7) | 44 (2.9) | 4.11 (2.57–6.59) | 1.33 (0.62–2.86) |

| Sociodemographic factors | ||||

| Maternal age (years) | ||||

| Median age (interquartile range) | 29 (25–33) | 31 (26–36) | 1.06 (1.04–1.08) | 1.06 (1.04–1.09) |

| Five‐year age bandsb | ||||

| <20 | 17 (4.4) | 101 (6.7) | 0.94 (.52–1.72) | 0.84 (0.36–1.99) |

| 20–24 | 49 (12.8) | 275 (18.1) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| 25–29 | 86 (22.5) | 433 (28.6) | 1.11 (0.76–1.63) | 1.23 (0.72–2.12) |

| 30–34 | 105 (27.4) | 429 (28.3) | 1.37 (0.95–1.99) | 1.86 (1.10–3.15) |

| 35–39 | 93 (24.3) | 205 (13.5) | 2.55 (1.72–3.76) | 2.83 (1.62–4.95) |

| ≥40 | 33 (8.6) | 70 (4.6) | 2.65 (1.58–4.42) | 2.53 (1.25–5.15) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 3 (0.2) | Omitted | Omitted |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Non‐smoker | 238 (62.1) | 1181 (77.9) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Smoker | 95 (24.8) | 324 (21.4) | 1.45 (1.11–1.90) | 0.91 (0.61–1.36) |

| Missing | 50 (13.1) | 11 (0.7) | 22.56 (11.57–43.96) | 11.65 (4.50–30.17) |

| Substance misused | ||||

| No | 347 (90.6) | 1508 (99.5) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Yes | 30 (7.8) | 2 (0.1) | 65.02 (16.37–564.08) | 12.21 (2.33–63.98) |

| Missing | 6 (1.6) | 6 (0.4) | 4.34 (1.15–16.34) | Omitted |

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed | 236 (61.6) | 1118 (73.7) | 1 (Ref) | 1 |

| Unemployed | 60 (15.7) | 101 (6.7) | 2.81 (1.99–3.99) | 1.81 (1.08–3.04) |

| Missing | 87 (22.7) | 297 (19.6) | 1.39 (1.05–1.83) | 0.63 (0.40–0.97) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White European | 277 (72.3) | 1216 (80.2) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Indian | 17 (4.4) | 59 (3.9) | 1.26 (0.73–2.20) | 1.56 (0.77–3.19) |

| Pakistani | 19 (4.9) | 61 (4.0) | 1.37 (0.80–2.33) | 1.90 (0.96–3.76) |

| Bangladeshi | 6 (1.6) | 19 (1.3) | 1.39 (0.55–3.50) | 1.75 (0.51–6.03) |

| Other Asian | 7 (1.8) | 40 (2.6) | 0.77 (0.34–1.73) | 0.55 (0.19–1.57) |

| Black Caribbean | 6 (1.6) | 19 (1.3) | 1.39 (0.55–3.50) | 2.08 (0.58–7.48) |

| Black African | 33 (8.6) | 57 (3.8) | 2.54 (1.62–3.98) | 1.71 (0.89–3.25) |

| Others/Mixed | 18 (4.7) | 45 (2.9) | 1.76 (1.00–3.08) | 1.11 (0.51–2.41) |

Model 1 includes all variables specified in the table except parity, which was significantly correlated with previous pregnancy problems.

The ordered categorical variable for maternal age was analysed in a separate model.

Inadequate use of antenatal care: women who concealed pregnancy, were late bookers (>12 weeks) or did not receive minimal antenatal care.

For substance misuse, Fishers Exact test for univariable analysis was conducted;

Previous pregnancy problems: women who were reported to have suffered from any pregnancy‐related problem in a previous pregnancy, the major categories of which included thrombotic events, placental problems, haemorrhage, pre‐eclampsia, eclampsia, puerperal psychosis.

Pre‐existing medical problems: women who were reported to have any medical comorbidity during current pregnancy including the 16 specific conditions; Women were categorised as having gestational diabetes and anaemia during current pregnancy based on clinician recorded information in the medical records.

Excluded from the final model due to collinearity with previous pregnancy problems.

Obesity, gestational diabetes during current pregnancy, smoking and belonging to minority ethnic backgrounds were significantly associated with increased odds of death during univariable analysis, but their effects were attenuated after adjusting for other risk factors. Pre‐existing medical problems explained the apparent adverse effects of obesity and gestational diabetes during the current pregnancy. The observed higher odds of death among women who smoked decreased after adjusting for substance misuse, suggesting that it is the substance misusers among the smokers who are at an increased risk of dying. Univariable analysis showed that compared with white European women, the odds of dying was two and a half times higher among women from black African ethnic backgrounds (Table 1). However, on adding the variables gestational diabetes during current pregnancy, medical comorbidities, previous pregnancy problems and inadequate use of antenatal care, the adjusted odds ratio decreased towards null and was not significant at the 5% level, suggesting that these factors explained a substantial proportion of the increased odds of death among the black African women. Although not statistically significant, the odds ratios were raised for all ethnic minority groups.

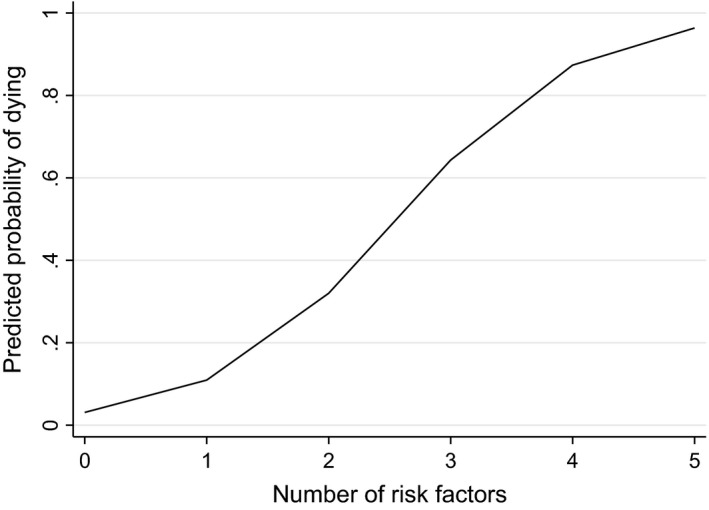

Analysis of the risk factor score showed that 5% (n = 19) of the cases had none of the seven identified risk factors compared with 33% (n = 506) of the controls. Among the cases 21% (n = 79), 34% (n = 131), 26% (n = 101) and 11% (n = 43) had one, two, three and four of these risk factors, respectively compared with 44% (n = 671), 18% (n = 273), 4% (n = 63) and 0.2% (n = 3) for the controls. Ten cases (3%) had five risk factors, but none of the controls had more than four risk factors. The probability of death increased linearly with increase in the number of risk factors (Figure 1). There was an almost four‐fold increase in the odds of death per unit increase in the number of risk factors (aOR 3.82; 95% CI 3.28–4.45; P < 0.001 for trend) after adjusting for other variables not included in the risk factor score. At a population level, 87% of the increased risk of maternal death in the UK could be attributed to the seven identified risk factors, the most important ones being medical comorbidities, maternal age ≥30 years and inadequate use of antenatal care services (Table 2). The calculated population attributable fractions for individual risk factors add up to more than 100% (Table 2) because several women had more than one risk factor.28 In addition, multivariable regression model 5 showed that after adjusting for the other associated factors, 13 of the 16 specific medical comorbidities examined were associated with increased odds of maternal death (see Supplementary material, Table S1).

Figure 1.

Incremental risk of death associated with an increase in the number of independent risk factors.

Table 2.

Population attributable fractions (PAF) for factors associated with increased risk of death

| Risk factors | PAF (%) | 95% CI (%) |

|---|---|---|

| All seven risk factors combined | 87 | 85–89 |

| Specific factors | ||

| Medical comorbidities | 66 | 63–68 |

| Age ≥30 years | 29 | 19–38 |

| Inadequate use of antenatal care | 24 | 23–25 |

| Previous pregnancy problems | 19 | 8–28 |

| Substance misuse | 7 | 5–8 |

| Anaemia during current pregnancy | 2 | 1–3 |

| Being unemployed | 1 | 0.8–9 |

Investigation of the association of newborn outcomes with maternal death in models 2, 3 and 4 showed that after adjusting for known risk factors, the odds of stillbirth, admission to NICU and death during the early neonatal period were higher among women who died compared with women who did not (Table 3). Among the women who died, 54 (14%) had a peri‐mortem caesarean section giving birth to 55 babies of which 26 (47%) were stillborn. Repeating the multivariable logistic regression analysis after removing the cases who had a peri‐mortem caesarean section still showed a significant association between maternal death and stillbirth (aOR 43.1; 99% CI 9.2–201.9, P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Fetal and infant outcomes for women who died compared with women with normal pregnancy

| Fetal outcomes | Mother died, n (%) | Mother alive, n (%) | Unadjusted OR (99% CI) | Adjusted ORa (99% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stillbirth (model 2) b | n = 383 | n = 1516 | ||

| No | 285 (74.4) | 1507 (99.4) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Yes | 54 (14.1) | 5 (0.3) | 34.0 (10.1–172.9) | 43.1 (9.2–201.9) |

| Missing | 44 (11.5) | 4 (0.3) | ||

| Admission to NICU (model 3) c | n = 329 | n = 1511 | ||

| No | 185 (56.2) | 1399 (92.6) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Yes | 100 (30.4) | 107 (7.1) | 7.1 (4.6–10.8) | 7.0 (3.9–12.6) |

| Missing | 44 (13.4) | 5 (0.3) | ||

| Death during infancy (model 4) c | n = 329 | n = 511 | ||

| No | 263 (79.9) | 1503 (99.5) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Yes | 14 (4.3) | 3 (0.2) | 26.6 (5.4–268.6) | 38.8 (5.1–297.3) |

| Missing | 52 (15.8) | 5 (0.3) |

Each outcome was tested in a separate multivariable analysis that controlled for all factors included in Table 1 as well as parity and hypertensive disorders during current pregnancy, all associations were significant at P < 0.001.

Analysis of stillbirth was restricted to women who did not have a perimortem caesarean section.

Analyses for admission to NICU and death during infancy were restricted to women who did not have a stillbirth.

Results of the sensitivity analysis for missing data were not different from the outputs of the multivariable model 1 for smoking, BMI, gestational diabetes during current pregnancy and anaemia during current pregnancy. However, re‐grouping the pregnant women with missing information about employment status as ‘employed’ significantly increased the odds of death among the unemployed (adjusted OR 2.04, 95% CI 1.23–3.38), whereas re‐grouping them as ‘unemployed’ reduced the odds (aOR 0.91, 95% CI 0.63–1.31), but this was not statistically significant at P < 0.05. Sensitivity analyses for missing information on stillbirth, NICU admission and early neonatal death did not change the observed associations between maternal death and these outcomes.

Discussion

Main findings

We found seven factors to be associated with direct and indirect maternal deaths in the UK in 2009–13: medical comorbidities, anaemia during current pregnancy, inadequate use of antenatal care services, previous pregnancy problems, substance misuse, being unemployed and increasing maternal age. These factors together contributed to 87% of the increased risk of maternal death from direct and indirect causes at the population level. Almost two‐thirds of the risk of maternal death from direct and indirect causes could be attributed to medical comorbidities and 13 specific conditions were found to be associated with these deaths although these were not necessarily the actual causes of death. The risk of stillbirth, admission to NICU and deaths during the early neonatal period was higher among the babies of women who died compared with women who did not.

Strengths and limitations

We were able to use 5 years of national data on maternal deaths from the MBRRACE‐UK and compare these with data from women who had an uncomplicated pregnancy and childbirth during 2009–13 to identify the factors that increase the risk of maternal deaths. The cases and controls were from the same source population, which makes this comparison valid and the findings are generalisable to all direct and indirect maternal deaths within 42 days of the end of pregnancy in the UK. However, we acknowledge that hospital controls are a higher risk group, so we are likely to have underestimated the true risks from maternal comorbidities, inadequate antenatal care and the other factors found to be significantly associated with maternal deaths in the UK.

Although the variables included in this study were comparable for the cases and controls, we cannot rule out bias due to the different data sources. We demonstrated an association between maternal death and stillbirth, NICU admission and early neonatal death, but there is a high degree of uncertainty around the estimated odds ratios due to the low number of these adverse outcomes among women who had an uncomplicated pregnancy and childbirth. Medical comorbidities and anaemia during current pregnancy are based on clinician‐reported general history, which does not define the severity and nature of these conditions, therefore additional studies are required for an in‐depth investigation.

Interpretation (in light of other evidence)

The findings of this study are comparable to two previous studies that examined the risk factors associated with progression from severe maternal morbidity to death in the UK;1, 2 however, this study includes all maternal deaths in the UK that resulted from direct or indirect causes during a period of 5 years (2009–13) and investigates the factors associated with maternal death compared with a general population of pregnant women. Similar to the study by Kayem et al.1 we found that increasing maternal age and being unemployed increased the odds of dying during pregnancy and childbirth, but we did not find obesity to be associated with mortality per se. As was observed in a previous study, the effect of obesity was mainly mediated by medical comorbidities.2 Belonging to minority ethnic backgrounds has been demonstrated to be associated with progression from severe morbidity to death in the UK;1, 2 although we observed an increased odds of death among women from all minority ethnic groups compared with white European women, these associations were not statistically significant. Other findings such as increased odds of medical comorbidities, inadequate use of antenatal care, previous pregnancy problems and substance misuse among women who died have been shown to be important risk factors for maternal death in the UK2, 29 and in other studies conducted in different countries.21, 30, 31, 32, 33

Although we found a significant association between anaemia during current pregnancy and maternal deaths from direct and indirect causes in the UK, the previous study that examined the factors associated with progression from severe morbidity to death did not find a significant association, although the adjusted odds ratio was 2.39 (95% CI 0.60–9.47).2 The quality of the available evidence about the specific clinical outcomes of maternal anaemia is low to moderate, but studies have shown iron deficiency anaemia to be associated with increased risk of maternal sepsis34 and postpartum haemorrhage,35, 36 which are direct causes of maternal death in the UK. Compared with the suggested high prevalence of iron deficiency anaemia (24%) among pregnant women in the UK,37 we found a smaller proportion of our study population to be diagnosed as having anaemia. Therefore, if anaemia is under‐diagnosed, it could actually be associated with a higher population‐attributable fraction than observed.

As shown by studies from the UK and other countries, individual medical comorbidities such as pre‐existing asthma, autoimmune diseases, inflammatory disorders and allergic/atopic conditions, cardiac disease, diabetes mellitus, epilepsy, haematological disorders, essential hypertension, infection, musculoskeletal disorders, mental health problems, renal problems and thrombotic events were associated with maternal mortality20, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44 and 66% of the risk of death from direct and indirect causes could be attributed to these conditions.

A study from Ethiopia that examined survival among neonates whose mothers died immediately or shortly after the end of pregnancy, found that children whose mothers die were 57 times more likely to die compared with those whose mothers survived after adjusting for socio‐economic and maternal demographic factors.4 The high risk of neonatal death was observed for maternal deaths within 42 days of the end of pregnancy as well as late deaths (after 42 days and before 1 year of end of pregnancy).4 Other studies from a number of low‐ and middle‐income countries have also shown similar higher risk of death among infants and children whose mothers die.5, 6 McClure et al.7 used data from 188 countries to examine the relationship between maternal deaths and stillbirths. The study showed a significant strong correlation (r = 0.72; P < 0.001) between maternal death and stillbirth with an overall 4.6 stillbirths for every maternal death along with a clear disparity in this correlation between high‐income and low‐ and middle‐income countries (high‐income countries 16.7 stillbirths per maternal death; low‐ and middle‐income countries 4.8 stillbirths per maternal death).7 Although this study showed a correlation, we were also able to conduct a multivariable logistic regression analysis using national data, which demonstrated a 43 times higher odds of stillbirth among women who died compared with women who were alive.

Conclusion

This national study demonstrates that seven factors, namely, medical comorbidities, increasing maternal age, inadequate use of antenatal care services, previous pregnancy problems, anaemia during current pregnancy, substance misuse and being unemployed, are associated with 87% of the increased risk of maternal deaths from direct and indirect causes at a population level in the UK. Reported high prevalence of iron deficiency anaemia among pregnant women in the UK suggests the need for further research to examine how different types of anaemia and their grade of severity are associated with maternal morbidity and mortality to develop clinical and policy guidance. Although statistically we were able to explain the higher odds of maternal death among ethnic minority groups (particularly among women from black African backgrounds) as being mediated by factors such as gestational diabetes, medical comorbidities, previous pregnancy problems and inadequate use of antenatal care, these women should still be considered a high‐risk group. The study reiterates the need for optimal care for women with medical comorbidities and increasing maternal age across the entire pregnancy care pathway, and the importance of adequate use of antenatal care services, but it also demonstrates the continuing existence of socio‐economic inequalities in maternal death in the UK.

Disclosure of interest

None declared. Completed disclosure of interests form available to view online as supporting information.

Contribution to authorship

MN coded the data, planned and carried out the analysis, and wrote the first draft of the article. MK designed the study, supervised the data collection, contributed to the analysis plan, and contributed to writing the article. JJK conceived and designed the study, contributed to the analysis plan and to the writing of the article.

Details of ethics approval

The London Multi‐centre Research Ethics Committee approved the UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS) general methodology (04/MRE02/45).

Funding

MK is funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Research Professorship. The Maternal, Newborn and Infant Clinical Outcome Review Programme, delivered by MBRRACE‐UK, is commissioned by the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP) on behalf of NHS England, NHS Wales, the Health and Social Care Division of the Scottish government, The Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety (DHSSPS), Northern Ireland, the States of Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man. The funding sources had no role in the study, and the researchers were independent from the funders. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, HQIP, the NIHR or the Department of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Supporting information

Table S1. Medical co‐morbidities associated with direct and indirect maternal deaths (Model‐5*).

Nair M, Knight M, Kurinczuk JJ. Risk factors and newborn outcomes associated with maternal deaths in the UK from 2009 to 2013: a national case–control study. BJOG 2016;123: 1654–1662.

Linked article This article is commented on by J Drife p. 1663 in this issue. To view this mini commentary visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14024.

References

- 1. Kayem G, Kurinczuk J, Lewis G, Golightly S, Brocklehurst P, Knight M. Risk factors for progression from severe maternal morbidity to death: a national cohort study. PLoS One 2011;6:e29077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nair M, Kurinczuk JJ, Brocklehurst P, Sellers S, Lewis G, Knight M. Factors associated with maternal death from direct pregnancy complications: a UK national case–control study. BJOG 2015;122:653–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Antenatal Care [CG62]. London: NICE, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moucheraud C, Worku A, Molla M, Finlay JE, Leaning J, Yamin AE. Consequences of maternal mortality on infant and child survival: a 25‐year longitudinal analysis in Butajira Ethiopia (1987‐2011). Reprod Health 2015;12 (Suppl 1):S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clark SJ, Kahn K, Houle B, Arteche A, Collinson MA, Tollman SM, et al. Young children's probability of dying before and after their mother's death: a rural South African population‐based surveillance study. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Houle B, Clark SJ, Kahn K, Tollman S, Yamin A. The impacts of maternal mortality and cause of death on children's risk of dying in rural South Africa: evidence from a population based surveillance study (1992–2013). Reprod Health 2015;12 (Suppl 1):S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McClure EM, Goldenberg RL, Bann CM. Maternal mortality, stillbirth and measures of obstetric care in developing and developed countries. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2007;96:139–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vogel JP, Souza JP, Mori R, Morisaki N, Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M, et al. Maternal complications and perinatal mortality: findings of the World Health Organization Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health. BJOG 2014;121 (Suppl 1):76–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Manktelow BM, Smith LK, Evans TA, Hyman‐Taylor P, Kurinczuk JJ, Field DJ, et al. Perinatal Mortality Surveillance Report UK Perinatal Deaths for Births from January to December 2013. Leicester: The Infant Mortality and Morbidity Group, Department of Health Sciences, University of Leicester, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10. National Records of Scotland . Vital events reference tables 2013. Section 4: stillbirths and infant deaths. 2013. [www.nrscotland.gov.uk/statistics-and-data/statistics/statistics-by-theme/vital-events/general-publications/vital-events-reference-tables/2013/section-4-stillbirths-and-infant-deaths]. Accessed 22 July 2015.

- 11. Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency . Stillbirths and infant deaths. 2013. [www.nisra.gov.uk/demography/default.asp9.htm]. Accessed 22 July 2015.

- 12. Office for National Statistics . Death registrations summary tables, England and Wales, 2013. 2014. [www.ons.gov.uk/ons/publications/re-reference-tables.html?edition=tcm%3A77-317522] Accessed 22 July 2015.

- 13. Kurinczuk JJ, Draper ES, Field DJ, Bevan C, Brocklehurst P, Gray R, et al. Experiences with maternal and perinatal death reviews in the UK – the MBRRACE‐UK programme. BJOG 2014;121:41–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Knight M, Kenyon S, Brocklehurst P, Neilson J, Shakespeare J, Kurinczuk JJ. (eds), et al. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care – Lessons Learned to Inform Future Maternity Care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2009–12. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Knight M, Kurinczuk JJ, Tuffnell D, Brocklehurst P. The UK obstetric surveillance system for rare disorders of pregnancy. BJOG 2005;112:263–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Knight M, Lindquist A. The UK obstetric surveillance system: impact on patient safety. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2013;27:621–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency . Registrar general annual reports. [www.nisra.gov.uk/demography/default.asp22.htm]. Accessed 17 July 2013.

- 18. Goffman D, Madden RC, Harrison EA, Merkatz IR, Chazotte C. Predictors of maternal mortality and near‐miss maternal morbidity. J Perinatol 2007;27:597–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Souza JP, Cecatti JG, Faundes A, Morais SS, Villar J, Carroli G, et al. Maternal near miss and maternal death in the World Health Organization's 2005 global survey on maternal and perinatal health. Bull World Health Organ 2010;88:113–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mhyre JM, Bateman BT, Leffert LR. Influence of patient comorbidities on the risk of near‐miss maternal morbidity or mortality. Anesthesiology 2011;115:963–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nair M, Kurinczuk JJ, Knight M. Ethnic variations in severe maternal morbidity in the UK – a case–control study. PLoS One 2014;9:e95086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Knight M, Tuffnell D, Brocklehurst P, Spark P, Kurinczuk JJ, on behalf of UKOSS . Incidence and risk factors for amniotic‐fluid embolism. Obstet Gynecol 2010;115:910–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Office for National Statistics . Ethnic Group Statistics: A Guide for the Collection and Classification of Ethnicity Data. Newport: Office for National Statistics, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Royston P, Ambler G, Sauerbrei W. The use of fractional polynomials to model continuous risk variables in epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol 1999;28:964–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. World Health Organization . Global strategy on diet, physical activity and health. 2015. [www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/childhood_what/en/]. Accessed 2 July 2015.

- 26. Lindquist A, Knight M, Kurinczuk JJ. Variation in severe maternal morbidity according to socioeconomic position: a UK national case–control study. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Greenland S, Drescher K. Maximum likelihood estimation of the attributable fraction from logistic models. Biometrics 1993;49:865–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rowe AK, Powell KE, Flanders WD. Why population attributable fractions can sum to more than one. Am J Prevent Med 2004;26:243–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Waterstone M, Bewley S, Wolfe C. Incidence and predictors of severe obstetric morbidity: case‐control study. BMJ 2001;322:1089–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Oladapo OT, Sule‐Odu AO, Olatunji AO, Daniel OJ. “Near‐miss” obstetric events and maternal deaths in Sagamu, Nigeria: a retrospective study. Reprod Health 2005;2:9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sachs BP, Brown D, Driscoll SG, Schulman E, Acker D, Ransil BJ, et al. Maternal mortality in Massachusetts. Trends and prevention. N Engl J Med 1987;316:667–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shen FR, Liu M, Zhang X, Yang W, Chen YG. Factors associated with maternal near‐miss morbidity and mortality in Kowloon Hospital, Suzhou, China. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2013;123:64–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Danel I, Berg C, Johnson CH, Atrash H. Magnitude of maternal morbidity during labor and delivery: United States, 1993–1997. Am J Public Health 2003;93:631–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Acosta CD, Bhattacharya S, Tuffnell D, Kurinczuk JJ, Knight M. Maternal sepsis: a Scottish population‐based case–control study. BJOG 2012;119:474–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Arnold DL, Williams MA, Miller RS, Qiu C, Sorensen TK. Iron deficiency anemia, cigarette smoking and risk of abruptio placentae. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2009;35:446–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kavle JA, Stoltzfus RJ, Witter F, Tielsch JM, Khalfan SS, Caulfield LE. Association between anaemia during pregnancy and blood loss at and after delivery among women with vaginal births in Pemba Island, Zanzibar, Tanzania. J Health Popul Nutr 2008;26:232–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Barroso F, Allard S, Kahan BC, Connolly C, Smethurst H, Choo L, et al. Prevalence of maternal anaemia and its predictors: a multi‐centre study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2011;159:99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wen SW, Huang L, Liston R, Heaman M, Baskett T, Rusen ID, et al. Severe maternal morbidity in Canada, 1991–2001. Can Med Assoc J 2005;173:759–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Clowse ME, Jamison M, Myers E, James AH. A national study of the complications of lupus in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;199:127.e1–e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. James AH, Bushnell CD, Jamison MG, Myers ER. Incidence and risk factors for stroke in pregnancy and the puerperium. Obstet Gynecol 2005;106:509–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kadir RA, Lee CA, Sabin CA, Pollard D, Economides DL. Pregnancy in women with von Willebrand's disease or factor XI deficiency. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1998;105:314–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jeng J‐S, Tang S‐C, Yip P‐K. Incidence and etiologies of stroke during pregnancy and puerperium as evidenced in Taiwanese women. Cerebrovasc Dis 2004;18:290–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Villers MS, Jamison MG, De Castro LM, James AH. Morbidity associated with sickle cell disease in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;199:125.e1–e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Adeoye IA, Onayade AA, Fatusi AO. Incidence, determinants and perinatal outcomes of near miss maternal morbidity in Ile‐Ife Nigeria: a prospective case–control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013;13:93–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Medical co‐morbidities associated with direct and indirect maternal deaths (Model‐5*).