Abstract

Novel antimalarial therapies are needed in the face of emerging resistance to artemisinin combination therapies. A previous study found a high cure rate in Mozambican children with uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria 7 days after combination treatment with fosmidomycin-clindamycin. However, 28-day cure rates were low (45.9%), owing to parasite recrudescence. We sought to identify any genetic changes underlying parasite recrudescence. To this end, we used a selective whole-genome amplification method to amplify parasite genomes from blood spot DNA samples. Parasite genomes from pretreatment and postrecrudescence samples were subjected to whole-genome sequencing to identify nucleotide variants. Our data did not support the existence of a genetic change responsible for recrudescence following fosmidomycin-clindamycin treatment. Additionally, we found that previously described resistance alleles for these drugs do not represent biomarkers of recrudescence. Future studies should continue to optimize fosmidomycin combinations for use as antimalarial therapies.

Keywords: Malaria, fosmidomycin, recrudescence, Plasmodium, clindamycin, whole genome amplification

Malaria remains a serious global health concern, with approximately 214 million cases of and 483 000 deaths due to malaria in 2015 [1]. A majority of severe malaria cases occur in pregnant women and children <5 years of age and result from infection with the parasite Plasmodium falciparum [1]. Artemisinin combination therapies (ACTs) represent the current first-line treatment in areas of endemicity. Historically, the development of drug resistance has hindered malaria control. As delayed parasite clearance has emerged for ACTs in Southeast Asia and has continued to spread [1, 2], new antimalarials are urgently needed.

One such potential therapeutic is the phosphonic acid antibiotic fosmidomycin (FSM). FSM is a well-characterized inhibitor of the first committed step of isoprenoid precursor synthesis via the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway [3–5]. Because humans synthesize isoprenoids via an enzymatically distinct metabolic route (the mevalonate pathway), FSM is a highly specific inhibitor of malaria parasite growth [3, 5] and is well tolerated in humans [6, 7].

FSM was originally developed as an antibacterial [8] and is currently under evaluation as a partner agent for combination therapy against uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria (clinical trials registration NCT02198807). Several studies have paired FSM with the antibiotic clindamycin (CLN), a protein translation inhibitor (clinical trials registration NCT02198807, NCT01361269, NCT01002183, NCT00214643, and NCT00217451) [6, 9, 10]. One such phase 2 clinical trial, performed in Mozambique in 2010, evaluated the efficacy of a FSM-CLN combination against uncomplicated malaria in children aged 6–35 months, the youngest cohort tested to date [11, 12]. A high parasite cure rate was observed at day 7 after treatment with FSM-CLN (94.6%). Unfortunately, the cure was not durable, and the posttreatment polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–corrected day 28 cure rate was 45.9% (17 of 39), due to recrudescent infections. Parasite recrudescence is common in clinical studies of FSM efficacy, with an overall day 28 cure rate of approximately 70% in adults [12].

The safety and specificity of MEP pathway–targeting therapeutics such as FSM are highly desirable. However, the failure of FSM treatment to result in lasting cure has led to concern regarding the clinical utility of FSM or related antimalarials. We recently found that FSM resistance is readily achieved in culture owing to mutations in the metabolic regulator PfHAD1 (PlasmoDB ID PF3D7_1033400) [13]. Additionally, CLN resistance, attributed to a mutation in the apicoplast 23S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) [14], has been reported in clinical isolates of P. falciparum.

In this study, we address whether observed recrudescence is produced by selection for mutations in previously identified candidate genes or novel resistance loci. Using selective whole-genome amplification (SWGA) and sequencing, we characterized P. falciparum field isolates obtained from blood spot samples to evaluate the genetic landscape of drug resistance before and after FSM-CLN treatment. Specifically, we evaluated enrichment in genetic changes associated with decreased susceptibility to either FSM or CLN.

METHODS

Study Information

The study criteria have been previously described [11]. The study evaluated 37 children ages 6–35 months with uncomplicated malaria. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are outlined in the original study [11]. Patients were administered a 3-day, twice-daily course of oral FSM-CLN. Blood spots were collected at days 0, 7, 14, and 28 and, if applicable, upon recrudescence.

Clinical Trial Information

The original trial in Mozambique, sponsored by Jomaa Pharma, was conducted in 2010 according to the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use good clinical practice guidelines. The protocol was approved by the National Mozambican Ethics Review Committee and the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona Ethics Review Committee. The study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01464138).

Selective Whole Genome Amplification

Blood spotting and DNA isolation has been previously described [11]. SWGA of P. falciparum genomes was performed as described previously [15], including primer sets (Supplementary Table 2) and reaction conditions. Reactions contained 10 ng of template and 3.5 μM of primer set 6A. Reactions were cleaned using Ampure beads (Beckmann Coulter) at a 1:1 DNA to bead ratio. Samples underwent a second round of SWGA, using primer set 8A and 15–30 ng of DNA.

PCR of SWGA Products

Selective amplification of P. falciparum genomes was verified by PCR, using P. falciparum– or human-specific primers (Supplementary Table 1). Human DNA and human-specific primers were kindly provided by Shiming Chen (Washington University). Reactions contained 2 μM each primer, 25–50 ng of bead-cleaned SWGA product, and BIO-X-ACT Short PCR Mix (Bioline). Vendor-recommended cycling conditions were used, with modifications: annealing at 55°C and 60°C for P. falciparum– and human-specific primers, respectively, and extension at 68°C. Amplicons were visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Whole-Genome Sequencing

Library preparation, Illumina sequencing, read alignments, and variant calling were performed by the Washington University Genome Technology Access Center. Bead-cleaned SWGA product DNA (0.5–1.2 µg) was sheared and subjected to end repair and adapter ligation. PCR-based libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 to generate 101–base pair paired end reads. Reads were aligned to the 3D7 reference (PlasmoDB v24) using Novoalign (V2.08.02) [16]. Duplicate reads were removed. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were called using samtools (mpileup) [17], filtered (quality, ≥20; read depth, ≥5), and annotated using snpEff (3.3c, build 2013-06-28) [18].

P. falciparum reads are available through the National Center for Biotechnology Information BioProject database (PRJNA315887) and Sequence Read Archive (SRP072442).

For some analyses (comparison of SNPs in resistance genes and gene ontology [GO] analysis), only sample pairs with both exomes showing sufficient coverage (≥60% covered at ≥5X, as indicated in Supplementary Table 3) were used. Given a per-base error rate of 0.1%–0.5% for Illumina sequencing [19, 20], 5X coverage equates to >99.9% accuracy. Studies have indicated reasonable sensitivity and accuracy for our variant caller at this cutoff [21].

SNPhylo Plot Generation

Multisample variant call formats were converted to hapmap format. SNPhylo [22] was run with the default settings, with a linkage disequilibrium cutoff of 0.8.

Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) Determination

MOI was determined using the World Health Organization (WHO)–recommended PCR-based genotyping procedures at the MSP1 (PF3D7_0930300), MSP2 (PF3D7_0206800), and GLURP (PF3D7_1035300) loci [23].

Sequencing of the Apicoplast 23S rRNA Locus

The apicoplast 23S rRNA (PlasmoDB ID PCF10_API0010:rRNA) locus was amplified by PCR. Reactions contained 2 µM of each primer 23S_1 and 23S_6 (Supplementary Table 1), 4–5 µL of blood spot DNA, and CloneAmp HiFi PCR Premix (Clontech). Vendor-recommended cycling conditions were used (55°C primer annealing).

Amplicons were Sanger sequenced using primers 23S_1–23S_6 (Supplementary Table 1).

GO Analysis

GO term enrichment of genes containing SNPs unique to posttreatment samples was determined using the PlasmoDB Gene Ontology Enrichment tool [24] (Bonferroni-corrected P<.01).

RESULTS

SWGA of Blood Spot DNA Generates Parasite Templates for Whole-Genome Sequencing

We evaluated blood spot DNA (mixed human and P. falciparum) from 12 patient samples with microscopic recrudescent infection (12 pretreatment and posttreatment pairs, for a total of 24 samples). Pilot unmodified, low-input library preparation methods resulted in <5% reads mapping to the P. falciparum genome. For this reason, we used SWGA to amplify P. falciparum DNA. This method uses the processive Φ29 DNA polymerase and genome-specific primers to selectively amplify a target genome from a mixed sample [25–27] and has been recently used to characterize chimpanzee Plasmodium genomes [15].

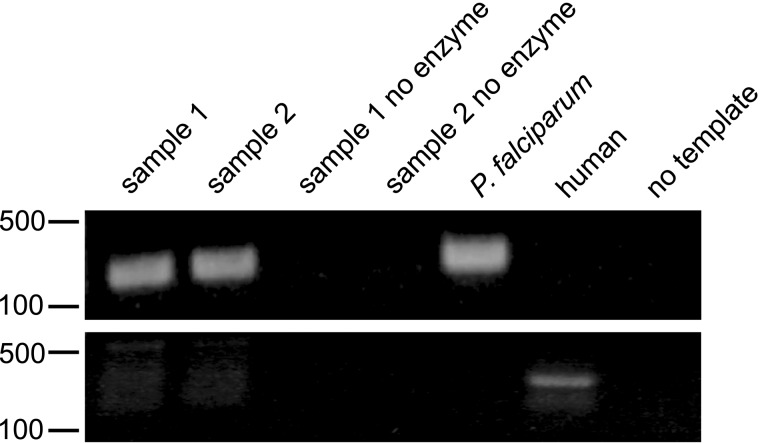

Enrichment of the P. falciparum genome was verified by PCR (Figure 1). We amplified P. falciparum genomes from a broad range of parasite densities (18–315 064 parasites/µL whole blood). Amplified samples were used to prepare libraries for Illumina sequencing.

Figure 1.

Selective whole-genome amplification (SWGA) causes enrichment of Plasmodium falciparum DNA from mixed samples that can be detected by polymerase chain reaction. Shown is an agarose gel of SWGA amplicons obtained using P. falciparum–specific (top) and human-specific (bottom) primers. Samples are numbered by infection and were obtained before or after treatment. Markers indicate DNA size in base pairs.

The samples displayed varying degrees of sequencing success (Supplementary Table 3). An average (±standard error of the mean [SEM]) of 55.1% ± 2.9% of reads mapped to the P. falciparum genome, resulting in 48.1% ± 3.5% of the genome covered at ≥5X. This is comparable to findings of previous studies that used SWGA to sequence microbial genomes [27, 28]. The genome coverage we obtained was consistent with very low proportions (<0.01%) of parasite DNA in the blood spot samples [15]. While more reads will increase genome coverage, including typically low-coverage intragenic regions, coverage is likely to be limited by incomplete genome representation in the sample, as very low proportions of parasite DNA are likely to result in incomplete or inefficient SWGA of some genome regions. Given the low coverage of AT-rich intragenic regions, our analyses focused on protein-coding regions of the P. falciparum genome. We observed an average (±SEM) of 69.0% ± 4.4% of the exome covered ≥5X, with as much as 90% of the exome covered ≥5X (Supplementary Table 3).

We observed an average (±SEM) of 35 451 ± 1220 total genome SNPs in our sequenced samples, consistent with recent studies of African field isolates [29, 30]. Of these, an average (±SEM) of 15 862 ± 534 were exome SNPs. We found an average (±SEM) of 10 755 ± 349 nonsynonymous SNPs in our samples with sufficient exome coverage (≥60% covered at ≥5X).

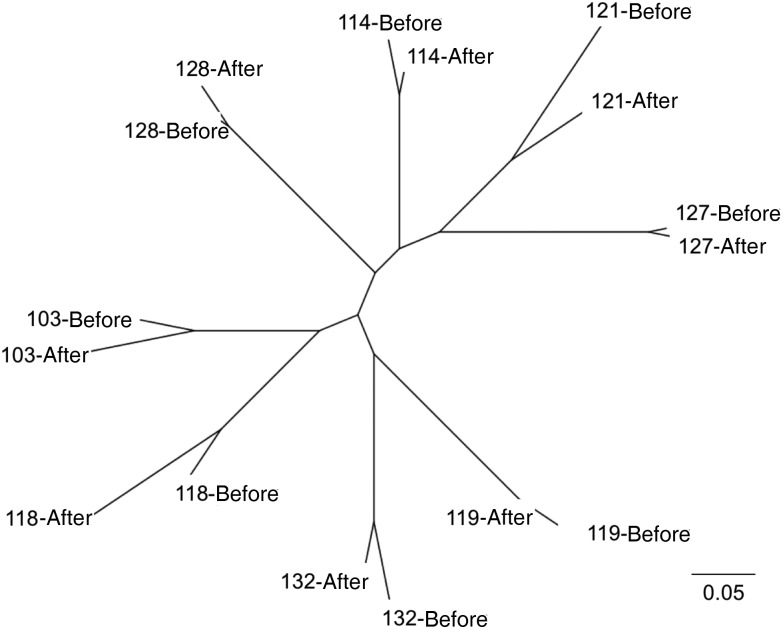

SNP Profiling Confirms Recrudescent Infections

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree construction from our exome SNP profiles from the 12 pretreatment and posttreatment sample pairs demonstrated clustering by patient of origin (Figure 2). These data support the conclusion that all infections analyzed indeed reflected failure to completely clear the original infection (recrudescence), as opposed to novel, independent infections. Pretreatment and posttreatment samples shared a majority (average [±SEM], 66.0% ± 3.4%) of nonsynonymous SNPs, while independent (between-patient) pretreatment infections were less related and shared only 24.6% ± 0.4% of nonsynonymous SNPs (strains with ≥60% of the exome at ≥5X; n = 8). These data confirm the genotyping findings reported in the original study [11], which established recrudescence through WHO-recommended PCR-based genotyping at 3 P. falciparum loci: MSP1, MSP2, and GLURP [23].

Figure 2.

Samples cluster by patient, indicating recrudescent infections. SNPhylo [22] was used to construct a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) profiles from initial (before treatment) and recrudescent (after treatment) infections. Bootstrap values were 100 for all pretreatment and posttreatment branch points. Samples are numbered by infection. Scale bar represents units of substitution.

MOI Before and After Treatment

In high-transmission areas, patients may be simultaneously infected with multiple parasite strains. This genetic variation provides a potential reservoir for the development of resistance to antimalarials, both within a given patient and in the larger P. falciparum population. The MOI has been shown to decrease after recrudescence following chloroquine treatment [31], and, unsurprisingly, an increased MOI is correlated with treatment failure [32]. However, during any individual infection, selective pressures during infection (such as immune evasion) and drug treatment are expected to decrease genetic diversity. We therefore assessed MOI before and after recrudescence.

All infections were polyclonal, with a mean pretreatment MOI (±SEM) of 3.9 ± 0.3. This is slightly higher than MOIs reported in other pediatric studies in Mozambique [33, 34]. MOIs decreased modestly in two thirds of the samples after treatment and recrudescence, with a mean posttreatment MOI (±SEM) of 3.2 ± 0.2 (P = .0065, by the paired t test). This reduction was not a result of lower parasitemia densities in recrudescent infections, as the average posttreatment parasite density was approximately equal to the average (±SEM) pretreatment parasite density (76 225 ± 33 944 vs 70 977 ± 20 498 parasites/µL). Additionally, MOI and parasite density were not correlated (Pearson r = −0.041; P = .849).

Of note, loss-of-function mutations in the FSM-resistance gene PfHAD1 have been infrequently reported in the genomes of field P. falciparum isolates (PlasmoDB; accessed April 2016), suggesting that such alleles are rare [24]. Therefore, if resistance emerges during the course of infection in a given patient, recrudescence due to outgrowth of a rare resistant clone should result in a dramatic decrease in MOI. This was not observed in our population, suggesting that FSM resistance alone is unlikely to account for recrudescence of patients treated with FSM-CLN.

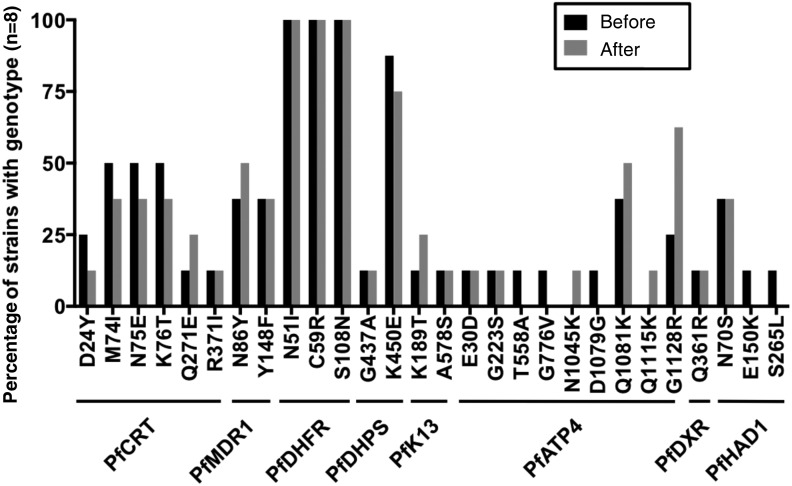

Genotyping of Known Resistance Loci Does Not Reveal a Change in the Resistance Landscape Between Pretreatment and Posttreatment Samples

To evaluate whether FSM-CLN recrudescent parasites have genetic changes associated with drug resistance, we investigated the genomes of paired pretreatment and posttreatment parasites for genetic markers of antimalarial resistance. We evaluated loci previously implicated in resistance to FSM or CLN, as well as loci documented to contribute to resistance to other clinically available antimalarials.

FSM targets the isoprenoid synthesis enzyme 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase (PfDXR, PF3D7_1467300). Following FSM-CLN treatment, recrudescent samples were not enriched in alternative PfDXR alleles (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 4). One sample (114) possessed the Q361R PfDXR allele, previously reported in African isolates [24]. The homologous residue (R276) in FSM-susceptible Escherichia coli DXR (NCBI reference NP_414715.1) is identical to the mutated residue (361R). Therefore, the DXR Q361R variant is unlikely to confer FSM resistance.

Figure 3.

Resistance landscape before and after recrudescence. Only infection pairs with sufficient exome coverage were analyzed (≥60% at ≥5X; n = 8). Shown are the percentages of pretreatment and posttreatment samples with indicated nonreference (3D7) alleles at resistance loci. Any codons not shown match the 3D7 reference in all samples.

We have recently identified a metabolic regulator, PfHAD1, whose loss results in FSM resistance in cultured P. falciparum [13]. No PfHAD1 loss-of-function alleles were identified in our samples (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 4), consistent with a known lack of variation in this gene in field samples [24]. The N70S allele seen in a number of strains has been previously reported as a common wild-type variant [24], which does not confer FSM resistance [13]. Two pretreatment samples (103 and 118) possessed additional polymorphisms in PfHAD1, S265L and E150K, respectively (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 4). These alleles are not predicted to affect PfHAD1 function (PolyPhen-2 scores, <0.005 [benign]) [35] and are not enriched in the recrudescent samples. Altogether, our data indicate that known markers of FSM resistance in PfDXR and PfHAD1 do not emerge during the course of FSM treatment. Thus, known mechanisms of FSM resistance observed in the laboratory are unlikely to represent the underlying mechanism behind FSM-CLN failure. Since recrudescent parasites were not culture adapted, we cannot distinguish whether these parasites were resistant or just failed to be cleared. Therefore, it is possible that resistance-causing mutations in PfDXR, PfHAD1, or other loci might occur if parasites were exposed to drugs for longer periods.

Resistance to the FSM partner agent, CLN, has also been reported in P. falciparum [14]. In this previous study, mutation (A1875C) in the 23S rRNA locus (PFC10_API0010) was associated with an approximately 100-fold increase in the clindamycin half-maximal inhibitory concentration for clinical isolates [14]. Insufficient coverage of the plastid genome was obtained from whole-genome sequencing; we therefore used targeted gene amplification and sequencing to interrogate for polymorphisms in PFC10_API10010. No samples possessed the A1875C variant. All sequenced samples matched the FSM- and CLN-susceptible 3D7 control strain (Supplementary Data 1). Notably, from our sequencing of laboratory 3D7 and HB3 strains, we identified variations not reported in the genome reference (T451A, A454T, and 401insG; Supplementary Data 1) [24]. These changes may have emerged over time during culturing of laboratory isolates.

Finally, we interrogated the prevalence of other drug resistance markers before and after FSM-CLN treatment (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 4). Specifically, we evaluated variation in the locus encoding the multidrug transporter PfMDR1 (PF3D7_0523000), which modulates parasite susceptibility to hydrophobic antimalarials, such as mefloquine and halofantrine [36]. Strains possessing PfMDR1 mutations are susceptible to FSM, and PfMDR1 mutations are not predicted to influence FSM effectiveness [3, 9]. Three PfMDR1 variants (wild type, Y184F, and N86Y) were identified in our analyzed strains, but PfMDR1 haplotype frequencies were not significantly different in pretreatment and posttreatment populations (P > .5).

ACTs, introduced in Mozambique in 2004 [37], may have selected for parasites able to withstand drug treatment, such as FSM-CLN. Alleles of PfK13 (Kelch13, PF3D7_1343700) have been implicated in artemisinin resistance. We identified 2 PfK13 variants in our population (K189T and A578S), neither of which has been implicated in laboratory artemisinin resistance. The K189T variant is common in African isolates [38, 39] and is not believed to cause increased clearance times following ACT. While the A578S variant has been associated with increased clearance times [40], this mutation was only observed in a small fraction of our strains. Additionally, strains possessing known resistance mutations in PfK13 are FSM susceptible (R. L. Edwards et al, unpublished data) suggesting that selection for artemisinin resistance does not result in FSM resistance.

In our small study population, selection with FSM-CLN did not appear to alter the frequency of PfMDR1 alleles or alleles of additional known genetic loci associated with antimalarial resistance, including PfCRT (chloroquine), PfATP4 (multiple drug classes), PfDHFR (antifolates), and PfDHPS (antifolates; Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 4) [41–45].

Our approach permitted an unbiased search for any novel nonsynonymous SNPs that are associated with recrudescence following FSM-CLN treatment. To better understand SNPs that were unique to or enriched in recrudescent samples, we also subtracted pretreatment nonsynonymous SNPs from posttreatment nonsynonymous SNPs. The 8 recrudescent strains analyzed had an average (±SEM) of 3448 ± 604 unique nonsynonymous SNPs (approximately 33% of their total nonsynonymous SNPs).

Sixty-eight SNPs were shared in ≥50% of the samples (Supplementary Table 5). However, no nosynonymous SNPs were shared between all 8 recrudescent samples, demonstrating that, in this small population, a genetic marker of recrudescence was not present.

Selective pressures in vivo are likely to be distinct from those described in vitro. We hypothesized that certain biological processes may be enriched for genetic variation in our posttreatment samples. We therefore performed GO analysis on the genes with SNPs shared in ≥50% of recrudescent samples (Supplementary Table 5) to understand the functions of genes containing SNPs enriched upon recrudescence. Our analysis revealed enrichment for immune evasion and parasitism-related functions (Table 1). This result has been observed in other studies of variation in P. falciparum populations [14, 30]. Because these genes are among the most variable in a population, they are likely to display changes in allele frequency following a population bottleneck, such as recrudescence. Notably, GO analysis did not reveal enrichment in pathways associated with drug resistance or with the mechanism of action of FSM (isoprenoid synthesis) or CLN (protein translation). While a novel genetic route to FSM or CLN resistance is possible, we see no evidence for enrichment of new SNPs or pathways in our unbiased genome analysis.

Table 1.

Gene Ontology (GO) Analysis of Genes Containing Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) Unique to Recrudescent Samples

| GO Term ID | Description | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| GO:0051704 | Multi-organism process | 1.5 × 10−4 |

| GO:0044403 | Symbiosis, encompassing mutualism through parasitism | 1 × 10−3 |

| GO:0044419 | Interspecies interaction between organisms | 1 × 10−3 |

| GO:0016337 | Cell-cell adhesion | 3.6 × 10−3 |

| GO:0009405 | Pathogenesis | 4.6 × 10−3 |

DISCUSSION

FSM is an antimalarial with a novel, parasite-specific mechanism of action; a well-characterized target; and exceptional clinical safety. Despite this promise, FSM combination treatment of uncomplicated P. falciparum infection in children was unsuccessful due to unacceptably high rates of parasite recrudescence [11]. Parasite FSM resistance arises readily in culture and has been attributed to loss-of-function mutations in PfHAD1 [13]. These in vitro studies suggested that selection for FSM resistance alleles during clinical infection and/or FSM treatment may represent a mechanism to explain clinical failures following FSM treatment.

To address this concern, we surveyed the genetic diversity in Mozambican pediatric P. falciparum infections before and after treatment failure with FSM-CLN. Overall, our data indicate that drug resistance does not account for treatment failures following FSM-CLN therapy. Our results confirm that treatment and recrudescence represent a population bottleneck, as the MOI is decreased in recrudescent samples. Since resistance alleles are thought to represent only a miniscule proportion of the pretreatment population, the modest decrease in MOI that we observed is inconsistent with the selection of resistant strains from the population.

Importantly, we did not find evidence of SNPs enriched in parasites following FSM-CLN treatment. Specifically, we did not identify enrichment for alleles already experimentally implicated in FSM or CLN resistance. Our use of whole-genome sequencing permitted an unbiased screen for additional SNPs that may contribute to resistance, regardless of whether these alleles are directly responsible for or otherwise associated with a recrudescent phenotype. While we were limited by the retrospective nature of our study and our inability to phenotype culture-adapted recrudescent parasites, both FSM and CLN have single, well-characterized targets and known SNPs underlying resistance [13, 14]. We therefore conclude that neither FSM nor CLN resistance was responsible for the clinical failure of FSM-CLN.

Our study was designed to evaluate the hypothesis that a simple coding mutation may underlie recrudescence in FSM-CLN–treated parasites. The results of our study cannot exclude other potential routes to resistance, such as noncoding mutations resulting in regulatory variation or nongenetic changes in gene expression or homeostatic responses. Further studies may address whether and how these mechanisms contribute to resistance to FSM, CLN, and other antimalarials.

Our study highlights an important caution in applying the results of forward genetic screening in cultured parasites to clinical populations. As resistance alleles are identified in vitro, it is important to recognize that selective pressures during natural human infection (immune pressure and metabolic requirements) are likely to be distinct. Our data indicate that mutation in PfHAD1 is not readily achieved in clinical populations. Perhaps mutation of PfHAD1 comes at a fitness cost in P. falciparum, similar to what has been found for other resistance loci, such as PfCRT and PfATP4 [46, 47]. However, PfHAD1 mutation appears to reduce fitness during human infection and not during culture, as loss of PfHAD1 is easily achieved in laboratory selections.

Finally, our study illustrates the usefulness of SWGA for the analysis of P. falciparum genomes from blood spot samples. This method has applications for future field studies, as blood spots are easier to acquire than whole blood. Further optimization will facilitate the extraction of more data from these types of samples. Furthermore, our data provide additional validation of PCR-based strategies to determine MOI and recrudescence. We found that the high rate of recrudescence following FSM-CLN treatment in children was not overestimated owing to use of the standard 3-locus PCR genotyping protocol [11]. Eventual use of whole-genome sequencing for genotyping field populations will provide more information regarding variation within a geographic region and within patients.

This work supports the current hypothesis that the disappointing clinical efficacy of FSM combinations is likely due to challenges of partner drug selection and formulation [12]. The short serum half-life of both FSM and CLN (1–3 hours) limits parasite exposure and presumably reduces the selective pressure for resistance [8, 48]. However, this limited serum exposure almost certainly contributes to decreased clinical efficacy. Currently, FSM is being evaluated in combination with the bisquinolone piperaquine in a phase 2 clinical trial in Gabon (clinical trials registration NCT02198807). Piperaquine has a notably long half-life (>20 days) [49], which holds promise to limit recrudescence when paired with FSM. Our findings support the continued development of antimalarials targeting PfDXR and the MEP pathway, as well as the development of alternative FSM combinations.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at http://jid.oxfordjournals.org. Consisting of data provided by the author to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the author, so questions or comments should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank the study participants at the Centro de Investigação em Saúde de Manhiça in Manhiça, Mozambique, for allowing us to analyze their parasite isolates; Philip Ruzycki (laboratory of Dr Shiming Chen, Washington University), for supplying human-specific primers and for helpful discussion regarding the analyses; Andrew Jezewski (Odom laboratory, Washington University), for helpful discussion regarding the analyses; and Wei (Will) Yang at the Genome Technology Access Center in the Department of Genetics at Washington University School of Medicine, for assistance with the analyses.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Children's Discovery Institute of Washington University and St. Louis Children's Hospital (MD-LI-2011-171 to A. R. O.), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health (R01AI103280 and R21AI123808 to A. R. O.; R01AI058715, R01AI091595, and R37AI050529 to B. H. H.; and T32AI007532 to S. A. S.), the March of Dimes (Basil O′Connor Starter Scholar Research Award to A. R. O.), the National Institute of General Medical Sciences at the National Institutes of Health (T32GM007067 to A. M. G.), the Washington University Monsanto Excellence Fund (graduate fellowship to A. M. G.), and the program Miguel Servet of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Plan Nacional de I+D+I 2008–2011; grant CP11/00269 to Q. B.). The Genome Technology Access Center at Washington University is partially supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (P30CA91842), the National Institutes of Health National Center for Research Resources (Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences/Clinical and Translational Science Award grant UL1TR000448), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research.

Potential conflicts of interest. D. H. is employed by Jomaa Pharma, which sponsored the original clinical trial, conducted in 2010 in Mozambique, and which played no role in the subsequent analyses presented in this study. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). World malaria report 2015. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashley EA, Dhorda M, Fairhurst RM et al. Spread of artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:411–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jomaa H, Wiesner J, Sanderbrand S et al. Inhibitors of the nonmevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis as antimalarial drugs. Science 1999; 285:1573–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koppisch AT, Fox DT, Blagg BSJ, Poulter CD. E. coli MEP synthase: steady-state kinetic analysis and substrate binding. Biochemistry 2002; 41:236–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang B, Watts KM, Hodge D et al. A second target of the antimalarial and antibacterial agent fosmidomycin revealed by cellular metabolic profiling. Biochemistry 2011; 50:3570–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lell B, Ruangweerayut R, Wiesner J et al. Fosmidomycin, a novel chemotherapeutic agent for malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2003; 47:735–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuemmerle HP, Murakawa T, Soneoka K, Konishi T. Fosmidomycin: a new phosphonic acid antibiotic. Part I: Phase I tolerance studies. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol 1985; 23:515–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuemmerle HP, Murakawa T, Sakamoto H, Sato N, Konishi T, De Santis F. Fosmidomycin, a new phosphonic acid antibiotic. Part II: 1. Human pharmacokinetics. 2. Preliminary early phase IIa clinical studies. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol 1985; 23:521–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiesner J, Henschker D, Hutchinson DB, Beck E, Jomaa H. In vitro and in vivo synergy of fosmidomycin, a novel antimalarial drug, with clindamycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002; 46:2889–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borrmann S, Issifou S, Esser G et al. Fosmidomycin-clindamycin for the treatment of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. J Infect Dis 2004; 190:1534–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lanaspa M, Moraleda C, Machevo S et al. Inadequate efficacy of a new formulation of fosmidomycin-clindamycin combination in Mozambican children less than three years old with uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56:2923–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandes JF, Lell B, Agnandji ST et al. Fosmidomycin as an antimalarial drug: a meta-analysis of clinical trials. Future Microbiol 2015; 10:1375–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guggisberg AM, Park J, Edwards RL et al. A sugar phosphatase regulates the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway in malaria parasites. Nat Commun 2014; 5:4467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dharia NV, Plouffe D, Bopp SER et al. Genome scanning of Amazonian Plasmodium falciparum shows subtelomeric instability and clindamycin-resistant parasites. Genome Res 2010; 20:1534–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sundararaman SA, Plenderleith LJ, Liu W et al. Genomes of cryptic chimpanzee Plasmodium species reveal key evolutionary events leading to human malaria. Nat Commun 2016; 7:11078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gardner MJ, Hall N, Fung E et al. Genome sequence of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nature 2002; 419:498–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2078–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang LL et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly 2012; 6:80–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wall JD, Tang LF, Zerbe B et al. Estimating genotype error rates from high-coverage next-generation sequence data. Genome Res 2014; 24:1734–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ross MG, Russ C, Costello M et al. Characterizing and measuring bias in sequence data. Genome Biol 2013; 14:R51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng AY, Teo Y-Y, Ong RT-H. Assessing single nucleotide variant detection and genotype calling on whole-genome sequenced individuals. Bioinformatics 2014; 30:1707–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee T-H, Guo H, Wang X, Kim C, Paterson AH. SNPhylo: a pipeline to construct a phylogenetic tree from huge SNP data. BMC Genomics 2014; 15:162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization. Venture M for M. Methods and techniques for clinical trials on antimalarial drug efficacy: genotyping to identify parasite populations. World Health Organization, 2008. Available at: http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/9789241596305/en/. Accessed 15 April 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aurrecoechea C, Brestelli J, Brunk BP et al. PlasmoDB: a functional genomic database for malaria parasites. Nucleic Acids Res 2009; 37:D539–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blanco L, Bernad A, Lázaro JM, Martín G, Garmendia C, Salas M. Highly efficient DNA synthesis by the phage phi 29 DNA polymerase. Symmetrical mode of DNA replication. J Biol Chem 1989; 264:8935–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garmendia C, Bernad A, Esteban JA, Blanco L, Salas M. The bacteriophage phi 29 DNA polymerase, a proofreading enzyme. J Biol Chem 1992; 267:2594–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leichty AR, Brisson D. Selective whole genome amplification for resequencing target microbial species from complex natural samples. Genetics 2014; 198:473–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seth-Smith HMB, Harris SR, Skilton RJ et al. Whole-genome sequences of Chlamydia trachomatis directly from clinical samples without culture. Genome Res 2013; 23:855–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mobegi VA, Duffy CW, Amambua-Ngwa A et al. Genome-wide analysis of selection on the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum in West African populations of differing infection endemicity. Mol Biol Evol 2014; 31:1490–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kidgell C, Volkman SK, Daily J et al. A systematic map of genetic variation in Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Pathog 2006; 2:e57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Happi CT, Gbotosho GO, Sowunmi A et al. Molecular analysis ofPlasmodium falciparum recrudescent malaria infections in children treated with chloroquine in Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2004; 70:20–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kyabayinze DJ, Karamagi C, Kiggundu M et al. Multiplicity of Plasmodium falciparum infection predicts antimalarial treatment outcome in Ugandan children. Afr Health Sci 2008; 8:200–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mayor A, Saute F, Aponte JJ et al. Plasmodium falciparum multiple infections in Mozambique, its relation to other malariological indices and to prospective risk of malaria morbidity. Trop Med Int Heal 2003; 8:3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rovira-Vallbona E, Moncunill G, Bassat Q et al. Low antibodies against Plasmodium falciparum and imbalanced pro-inflammatory cytokines are associated with severe malaria in Mozambican children: a case-control study. Malar J 2012; 11:181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods 2010; 7:248–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duraisingh MT, Cowman AF. Contribution of the pfmdr1 gene to antimalarial drug-resistance. Acta Trop 2005; 94:181–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lobo E, de Sousa B, Rosa S et al. Prevalence of pfmdr1 alleles associated with artemether-lumefantrine tolerance/resistance in Maputo before and after the implementation of artemisinin-based combination therapy. Malar J 2014; 13:300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Conrad MD, Bigira V, Kapisi J et al. Polymorphisms in K13 and falcipain-2 associated with artemisinin resistance are not prevalent in Plasmodium falciparum isolated from Ugandan children. PLoS One 2014; 9:e105690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Torrentino-Madamet M, Fall B, Benoit N et al. Limited polymorphisms in K13 gene in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Dakar, Senegal in 2012–2013. Malar J 2014; 13:472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hawkes M, Conroy AL, Opoka RO et al. Slow clearance of Plasmodium falciparum in severe pediatric malaria, Uganda, 2011–2013. Emerg Infect Dis 2015; 21:1237–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wellems TE, Walker-Jonah A, Panton LJ. Genetic mapping of the chloroquine-resistance locus on Plasmodium falciparum chromosome 7. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1991; 88:3382–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rottmann M, McNamara C, Yeung BKS et al. Spiroindolones, a potent compound class for the treatment of malaria. Science 2010; 329:1175–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Triglia T, Menting JG, Wilson C, Cowman AF. Mutations in dihydropteroate synthase are responsible for sulfone and sulfonamide resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997; 94:13944–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peterson DS, Walliker D, Wellems TE. Evidence that a point mutation in dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase confers resistance to pyrimethamine in falciparum malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1988; 85:9114–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Straimer J, Gnadig NF, Witkowski B et al. K13-propeller mutations confer artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum clinical isolates. Science 2014; 347:428–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jiménez-Díaz MB, Ebert D, Salinas Y et al. (+)-SJ733, a clinical candidate for malaria that acts through ATP4 to induce rapid host-mediated clearance of Plasmodium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014; 111:E5455–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ecker A, Lehane AM, Clain J, Fidock DA. PfCRT and its role in antimalarial drug resistance. Trends Parasitol 2012; 28:504–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DeHaan RM, Metzler CM, Schellenberg D, VandenBosch WD, Masson EL. Pharmacokinetic studies of clindamycin hydrochloride in humans. Int J Clin Pharmacol 1972; 6:105–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tarning J, Lindegårdh N, Annerberg A et al. Pitfalls in estimating piperaquine elimination. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005; 49:5127–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.