Abstract

Field effect or field cancerization denotes the presence of molecular aberrations in structurally intact cells residing in histologically normal tissues adjacent to solid tumors. Currently, the etiology of prostate field-effect formation is unknown and there is a prominent lack of knowledge of the underlying cellular and molecular pathways. We have previously identified an upregulated expression of several protein factors representative of prostate field effect, i.e., early growth response-1 (EGR-1), platelet-derived growth factor-A (PDGF-A), macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 (MIC-1), and fatty acid synthase (FASN) in tissues at a distance of 1 cm from the visible margin of intracapsule prostate adenocarcinomas. We have hypothesized that the transcription factor EGR-1 could be a key regulator of prostate field-effect formation by controlling the expression of PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN. Taking advantage of our extensive quantitative immunofluorescence data specific for EGR-1, PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN generated in disease-free, tumor-adjacent, and cancerous human prostate tissues, we chose comprehensive correlation as our major approach to test this hypothesis. Despite the static nature and sample heterogeneity of association studies, we show here that sophisticated data generation, such as by spectral image acquisition, linear unmixing, and digital quantitative imaging, can provide meaningful indications of molecular regulations in a physiologically relevant in situ environment. Our data suggest that EGR-1 acts as a key regulator of prostate field effect through induction of pro-proliferative (PDGF-A and FASN), and suppression of pro-apoptotic (MIC-1) factors. These findings were corroborated by computational promoter analyses and cell transfection experiments in non-cancerous prostate epithelial cells with ectopically induced and suppressed EGR-1 expression. Among several clinical applications, a detailed knowledge of pathways of field effect may lead to the development of targeted intervention strategies preventing progression from pre-malignancy to cancer.

Keywords: prostate cancer, field effect, protein factors

Introduction

Several pre-malignant states of prostate tissues have been previously described to indicate the progression to prostate adenocarcinoma (prostate cancer). Perhaps the most prominent histological deviation from normalcy is prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), which can manifest itself as a low- or high-grade form (1). All forms of PIN are characterized by the presence of intraluminal proliferation of the secretory cells of the duct acinar system and abnormal cytological features, including the ratio of nuclear-to-cytoplasmic area, the size of nucleoli, and the chromatin content (2). Another form of pre-malignancy is accepted to be proliferative inflammatory atrophy (PIA), which constitutes a possible link between inflammation and the malignant transformation of prostatic tissues (3). PIA is mainly recognized in low-magnification microscopy by a distinct hyperchromatic appearance of glandular components and variable acinar calibers, and a marked presence of inflammatory cells (4). Of note, both PIN and PIA are histologically evident lesions that are identifiable by trained surgical pathologists. However, it is reasonable to postulate that cell morphological changes leading to histologically abnormal appearances of prostate glands are preceded by molecular alterations that occur in complete absence of any cytological or histological change. This definition is in complete agreement with the concept of ‘field effect’ or ‘field cancerization’, two terms that are used interchangeably in this report to reflect contemporary research efforts. Originally introduced for renegade cancer cells outside the margins of squamous oral cell carcinoma (5), the updated definition excludes cellular and histological changes and focuses on molecular aberrations (6). Thus, ‘field-cancerized’ prostate tissues have been recently characterized by us and others (7–10) by genetic, epigenetic, and biochemical alterations in structurally intact epithelial and stromal cells of histologically normal tissues adjacent to prostate adenocarcinomas.

Along this line, we have recently described four protein factors of prostate field effect. These include the key transcription factor early growth response-1 (EGR-1), the lipogenic enzyme fatty acid synthase (FASN), and the secreted growth factors platelet-derived growth factor-A (PDGF-A) and macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 (MIC-1) (11–13). Our previous reports focused on emphasizing the similarity of the expressions of these factors between tumor tissues and their adjacent tissue areas, thereby supporting the concept of a field effect. Field effect in the prostate has been recognized to be of potential clinical value (7–10), which ideally necessitates an understanding of its underlying causative functional pathways. Towards this goal, the specific purpose of the present study was to explore a possible regulatory association between the transcription factor EGR-1 and the expression of PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN. Our primary focus was the analysis of this potential regulatory network by mining extensive datasets consisting of expression levels of EGR-1, PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN, in human prostate tissues. Findings from these analyses were corroborated by ectopic control of EGR-1 and its effect on PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN expression in the non-cancerous RWPE-1 human prostate epithelial cell model. Accordingly, our data indicate that the key transcription factor EGR-1 positively regulates PDGF-A and FASN, and negatively regulates MIC-1. These associations provide novel insight into the pathways underlying prostate field effect, which may lead to the development of targeted intervention strategies preventing progression from pre-malignancy to cancer.

Materials and methods

Tissues

The tissue cohort utilized in the present study represents a combination of the cohorts reported in our previous studies on prostate field effect (12,13). These tissues were collected in agreement with all Federal, State, and University laws, from consenting patients undergoing prostatectomy and donating ~100–500 mg of remnant tissue for molecular analyses. Individual cases of de-identified disease-free tissue samples were obtained from the Cooperative Human Tissue Network (CHTN) supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH; Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA). All tissues were available as formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections of 5-μm thickness [processed by the Department of Pathology, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center (Albuquerque, NM, USA) or provided by CHTN]. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center specifically approved the present study (#05-417). The combined tissue cohort consisted of 14 adenocarcinomas, 16 tumor-adjacent tissues, and 9 disease-free tissues. Twelve tumor-adjacent and tumor tissues were matched; for the missing unmatched tissues, the quality of data was insufficient for inclusion into the final results. The definition of the term ‘tumor-adjacent’ in our studies refers to tissue resected at a distance of ~1 cm from the visible tumor margin. The definition of the term ‘disease-free’ refers to prostate specimens from autopsy cases from individuals who died due to conditions unrelated to cancer. All tissues had been histologically reviewed previously by the surgical pathologist E.G. Fischer (Department of Pathology, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center), especially to exclude the presence of cryptic cancer cells in the tumor-adjacent prostate tissues (12,13). The mean age of all cases utilized was 56.1 years with a range of 26–79 years. The cancer specimens featured Gleason scores from 6 to 9 and pathological tumor node metastasis (TNM) stages (according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer; https://cancerstaging.org/Pages/default.aspx) from T2c to T3b (Table I).

Table I.

Demographics and clinical parameters of prostate tissues, and number of images analyzed.a

| Prostate tissues | Age (years) | TNMb | Gleason | No. of images analyzedc | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| EGR-1 | MIC-1 | PDGF-A | FASN | ||||||||

| Disease-free (CHTN) | |||||||||||

| 1 | 26 | Not applicable | Not applicable | 3 | 3 | -- | 3 | ||||

| 2 | 43 | Not applicable | Not applicable | 3 | 3 | -- | 3 | ||||

| 3 | 46 | Not applicable | Not applicable | 3 | -- | 3 | 4 | ||||

| 4 | 79 | Not applicable | Not applicable | 3 | 4 | 2 | -- | ||||

| 5 | 43 | Not applicable | Not applicable | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| 6 | 55 | Not applicable | Not applicable | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | ||||

| 7 | 55 | Not applicable | Not applicable | 3 | -- | -- | 4 | ||||

| 8 | 45 | Not applicable | Not applicable | 3 | -- | -- | 3 | ||||

| 9 | n/ad | Not applicable | Not applicable | 3 | -- | -- | -- | ||||

| Total | 27 | 16 | 10 | 25 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Prostate tissues | Age (years) | TNMb | Gleason | Tumor | Adjacent | ||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

| EGR-1 | MIC-1 | PDGF-A | FASN | EGR-1 | MIC-1 | PDGF-A | FASN | ||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Tumor and adjacent (UNMH/CHTN)e | |||||||||||

| 1 | 51 | n/ad | 7 (3+4) | -- | 3 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 2 | 54 | T3a | 7 (3+4) | -- | 3 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 3 (m) | 59 | T3b | 9 (4+5), 6 (3+3) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 4 (m) | 63 | T3a | 6 (4+3) | -- | 5 | 2 | -- | -- | 3 | 3 | -- |

| 5 (m) | 69 | T2c | 7 (4+3) | 3 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 6 (m) | 68 | T3b | 8 (5+3) | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 7 (m) | 55 | T2c | 8 (3+5) | 3 | 6 | 9 | -- | 6 | 6 | -- | -- |

| 8 (m) | 57 | T3a | 7 (4+3) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 9 (m) | 55 | T2c | 8 (3+5) | 3 | -- | 3 | 3 | 6 | -- | 3 | 9 |

| 10 (m) | 54 | T2–T3 | 6 (3+3) | -- | -- | -- | 3 | 6 | -- | 6 | 6 |

| 11 | 54 | T2c | 6 (3+3) | -- | -- | -- | -- | 9 | -- | 5 | 9 |

| 12 (m) | 64 | T3b | 6 (3+3) | 3 | -- | 4 | -- | 9 | -- | 4 | -- |

| 13 | 62 | T2c | 6 (3+3) | -- | -- | -- | -- | 9 | 9 | 9 | 16 |

| 14 (m) | 62 | T3b | 7 (4+3) | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 9 |

| 15 (m) | 44 | T2c | 6 (3+3) | 3 | -- | 3 | 4 | 5 | -- | -- | 6 |

| 16 | 58 | T2c | 9 (4+5) | -- | -- | -- | -- | 9 | -- | -- | 10 |

| 17 | 69 | T2c | 6 (3+3) | -- | -- | -- | -- | 9 | -- | -- | 12 |

| 18 (m) | 68 | T3a | 7 (3+4) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 6 | -- | 4 |

| Total | 30 | 37 | 42 | 30 | 92 | 41 | 45 | 93 | |||

A total of 14 adenocarcinomas (tumor), 16 tumor-adjacent tissues (adjacent), and 9 disease-free tissues were analyzed. In total, 488 images were queried (numbers for each case and marker are indicated). Specimens were collected at the University of New Mexico Hospital (UNMH; Albuquerque, NM, USA) or obtained from the CHTN.

TNM pathological stage was assigned using criteria published by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (https://cancerstaging.org/Pages/default.aspx).

--, indicates no available images of sufficient quality.

n/a, not available.

(m), indicates tumors that were matched with their corresponding adjacent tissues.

CHTN, Cooperative Human Tissue Network; TNM, tumor node metastasis; EGR-1, early growth response-1; MIC-1, macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1; PDGF-A, platelet-derived growth factor-A; FASN, fatty acid synthase.

Quantitative immunofluorescence

The generation of quantitative immunofluorescence data was reported in our previous studies on prostate field effect (12,13). These procedures included deparaffinization, antigen retrieval, and immunostaining using specific primary antibodies and Alexa Fluor 633-conjugated secondary antibodies. For reference purposes, we list here the specific reagents, while the experimental details have been described (12,13). The primary antibodies were: anti-EGR-1 mouse monoclonal antibody ab54966 (at 3 μg/ml); anti-MIC-1 goat polyclonal antibody ab39999 (at 3 μg/ml) (both from Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA); anti-PDGF-A rabbit polyclonal antibody sc-7958 (at 3 μg/ml); and anti-FASN rabbit polyclonal antibody sc20140 (H-300) (at 8 μg/ml) (both from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The corresponding control antibodies to ensure target specificity at the same concentrations were: normal mouse IgG (GC270; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), normal rabbit IgG (10500C), and normal goat IgG (10200) (both from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The corresponding secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor 633-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, Alexa Fluor 633-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG, and Alexa Fluor-conjugated rabbit anti-goat IgG (A21052, A21070, A21086, respectively; all from Invitrogen). Nuclear counterstaining was performed with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI).

Quantitative assessment of fluorescence was by spectral image acquisition and linear unmixing modes of confocal microscopy performed at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, Fluorescence Microscopy Shared Resource Core Facility, as described previously by us (12,13). Of note, control tissue slides with DAPI only, secondary antibody only, as well as unstained tissue were imaged separately to generate specific emission spectra for nuclear staining (DAPI; 405 nm excitation, 433 nm emission), Alexa Fluor (633 nm excitation, 490 nm emission), and background autofluorescence (ditto as per Alexa Fluor), respectively. These spectra were subjected to linear unmixing, a process that was equally applied to all spectral images to ensure the validity of inter-tissue comparisons. Consistent with our previous studies (12,13), quantification was achieved by digital imaging of the spectrally unmixed confocal images using two data acquisition modes. i) Whole-image analysis: the total Alexa Fluor 633 signal was ratio-normalized to the total DAPI signal to account for the number of cells and the cell density per slide, which tends to be different between cancerous and non-cancerous tissues. For EGR-1, the whole-image data acquisition mode was applied in three settings, i.e., whole-cell (no selection), nuclear selection, and cytoplasmic selection, according to its ability to translocate between the two cell compartments (14). ii) Region of interest (ROI) analysis: three representative ROIs (defined as areas with robust immunostaining) per slide were chosen and the cumulative signal specific for Alexa Fluor 633 was determined. The ROI acquisition mode was applied to all factors according to their typical expression, i.e., both nuclear and cytoplasmic for EGR-1, extranuclear for MIC-1 and PDGF-A, and cytoplasmic for FASN. The size of ROI was identical from image to image (~80 μm2 each) and they were chosen by persons blinded to the nature of the tissue (Mrs. Virginia Severns, Ms. Fiona Bisoffi, Ms. Suzanne Jones) to avoid bias (Fig. 1B). All original red signals were converted to yellow for better visibility. In total, 488 images with associated quantitative immunofluorescence data were available for the present analysis (Table I).

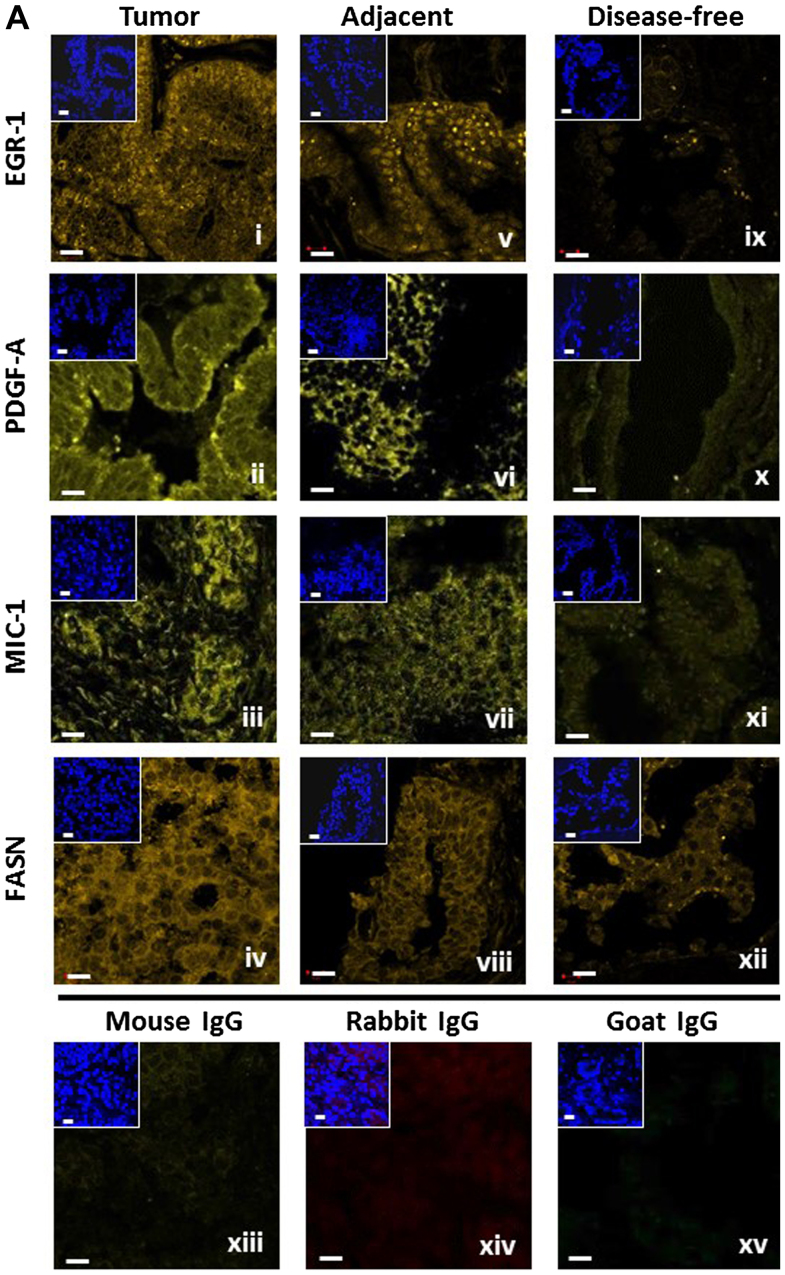

Figure 1.

(A) Representative detection of EGR-1, PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN by immunofluorescence in tumor (panels i–iv), tumor-adjacent (panels v–viii), and disease-free (panels ix–xii) human prostate tissues. Unspecific IgG of mouse, rabbit, and goat origin were tested for absence of staining (panels xiii–xv). Images represent Alexa Fluor 633 immunostaining (yellow signals); the smaller insets represent corresponding nuclear staining by DAPI (blue); white bars, 10 μm. (B) Schematic representation of the whole-image (top) and ROI (bottom) quantitative acquisition modes for EGR-1 fluorescence intensity. Whole-image data acquisition includes three different settings as defined by DAPI staining, whole-cell/no selection (panel i), nuclear (panel ii), and cytoplasmic (panel iii), as indicated by the bright blue shading. ROI data acquisition includes nuclear (panel iv) and extranuclear/cytoplasmic (panel v), as indicated by the areas designated by the randomly placed yellow rectangle frames (~80 μm2); white bars, 10 μm. EGR-1, early growth response-1; PDGF-A, platelet-derived growth factor-A; MIC-1, macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1; FASN, fatty acid synthase; ROI, region of interest.

Computational transcription factor binding site analysis

Computational searches for a potential transcription factor binding site were performed using the Tfsitescan software of the Molecular Informatics Resource for the Analysis of Gene Expression (MIRAGE) provided by the Institute for Transcriptional Informatics (IFTI; http://www.ifti.org/cgi-bin/ifti/Tfsitescan.pl). Genomic sequences for EGR-1, PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN were retrieved from the GRCh38 primary assembly of the gene database available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The specific reference sequences and locations were: NC_000005.10, Homo sapiens chromosome 5, location 138,465,492–138,469,315 for EGR-1; NC_000019.10, Homo sapiens chromosome 19, location 18,386,158–18,389,176 for MIC-1; NC_000007.14, Homo sapiens chromosome 7, location 497,258–520,123 for PDGF-A; and NC_000017.11, Homo sapiens chromosome 17, location 82,078,338–82,098,230 for FASN. The genomic sequences were subjected to searches for the EGR-1 recognition sequence [GCG(G/T)GGCG] (15).

Cell culture and transfections

Non-cancerous RWPE-1 human prostate epithelial cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured in serum-free keratinocyte basal medium containing 4,500 mg/l glucose, 0.05 mg/ml bovine pituitary extract and 5 ng/ml recombinant epidermal growth factor (Invitrogen). Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Trypsin-EDTA at 0.25% was used to detach the cells for splitting and reculturing. pcDNA3.1 control and pcDNA3.1/EGR-1 plasmids were a kind gift of Dr W. Xiao (University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, China). pLKO.1 control and pLKO.1/EGR-1 shRNA plasmids were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Plasmids were propagated in E. coli strain JM109 grown in LB broth containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin and purified using spin column chromatography (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA, USA). Transfections were performed with 1 μg plasmid DNA in 24-well plates containing 150,000 cells/well using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) for 48 h. Our transfection protocol yields reproducible transfection rates of 45±5% for pairs of empty control and cDNA-carrying plasmids (fluorescence-based assay, not shown). Cells were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen to preserve RNA integrity and stored short-term at −80°C.

Quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and western blotting

RNA was isolated using spin column chromatography (Qiagen, Inc.). A total of 1–3 μg of RNA was transcribed to cDNA using random decamers of the Retroscript™ RT Kit (Ambion/Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). mRNA expression was quantitated in a CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA) using the SYBR-Green PCR Master Mix and SYBR-Green RT-PCR Reagents Kit (Applied Biosystems/Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in 25-μl reactions, using 100 ng of template cDNA and a final primer concentration of 900 nM. The cycling parameters were 95°C for 5 min followed by 45 cycles of 94°C for 15 sec, and 51–58°C for 1 min. Primers were designed using Primer Express software (Invitrogen) and synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA, USA). The following primer sequences (5′→3′) were used: EGR-1 forward, GAGCAG CCCTACGAGCAC and reverse, AGCGGCCAGTATAGG TGATG; MIC-1 forward, CTACAATCCCATGGTGCTCAT and reverse, TCATATGCAGTGGCAGTCTTT; PDGF-A forward, CGTAGGGAGTGAGGATTCTTT and reverse, GCTTCCTCGATGCTTCTCTT; FASN forward, AGAACT TGCAGGAGTTCTGGGACA and reverse, TCCGAAGAA GGAGGCATCAAACCT; TATA-binding protein (TBP) forward, CACGAACCACGGCACTGATT and reverse, TTT TCTTGCTGCCAGTCTGGAC. qRT-PCR reactions were performed in triplicate. Relative expression levels were determined by the ΔΔCt method using TBP as normalization control after determining that amplification efficiencies were similar to the ones of the control transcripts.

Protein lysates were generated on ice in lysis buffer: 25 mM Tris, 8 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 15% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). Insoluble cell material was removed by centrifugation of lysates at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay (Sigma) against a bovine serum albumin (BSA) standard. Total protein (80 μg) was size-separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), electro-blotted onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes, blocked with 5% milk powder in Tris-buffered saline, and probed overnight with anti-EGR-1 and anti-β-actin primary antibodies (sc-189 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA and A1978 from Sigma, respectively). Detection and chemiluminescent visualization (Clarity ECL substrate; Bio-Rad) of EGR-1 and β-actin were performed using host-matched secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies (Sigma). The quantitative signal intensity of bands was determined by densitometry using ImageJ software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

Statistics

EGR-1, PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN expression levels were represented by signal intensities (sum pixel count per area) generated by quantitative immunofluorescence analysis (as described above). Straightforward, yet robust statistical methods were applied to the datasets using the Microsoft Excel software package (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). The datasets were inclusive (all available informative images), for matched cases only, or separated by the means. These approaches are indicated in the ‘Results’ section.

Correlations between the expressions of EGR-1 and PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN were analyzed by several statistical methods. To control for small sample size and a distribution with infinite variance due to tissue heterogeneity (expressed as coefficient of variation in %; reported in the text of ‘Results’), the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (as opposed to the Student's t-test) was used for pairs of datasets (reported in the text of ‘Results’). The single factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied for comparisons of multiple datasets with unequal variances. Statistical significance for the change of ratios of PDGF-A, MIC-1, or FASN to EGR-1 in tumor-adjacent and tumor tissues as compared to disease-free tissues was determined by the two-tailed Student's t-test (statistical significance defined as p≤0.05; Fig. 2A and B). The datasets were further mined for potential associations between factors by determining the Pearson's correlation coefficient (r). The significance for these observations was determined by first calculating the t-value of the correlation using the equation t = r/SQRT[(1 − r2)/(n−2)], where r is the correlation coefficient, n is the number of samples, and n−2 is the degree of freedom. The t-value was then used to determine the significance of r by the two-tailed Student's t-distribution (TDIST; statistical significance defined as p≤0.05; reported in the text, but not shown). Statistical significance for the change of ratios of positive to negative Pearson's correlations of PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN to EGR-1 in tumor-adjacent and tumor tissues as compared to disease-free tissues was determined by the F-test with p≤0.05 considered to be significant (Fig. 3B and D).

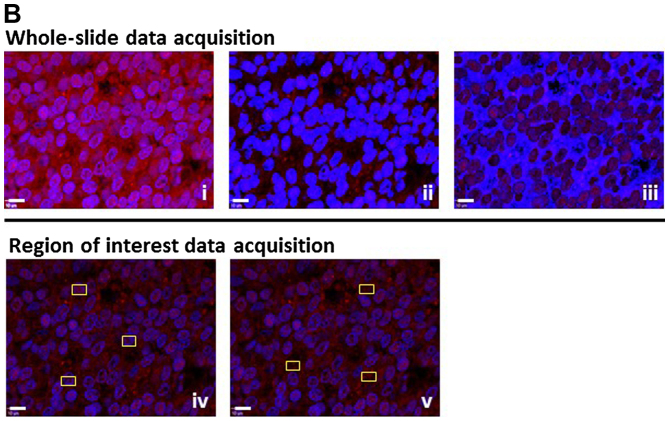

Figure 2.

(A and B) Ratios of PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN to EGR-1 expression (combined whole-cell, nuclear, cytoplasmic) in disease-free (DF), tumor-adjacent (ADJ), and tumor (TUM) tissues using images from all (left three bars) and matched only (right three bars) cases, acquired by the whole-image and the ROI mode, respectively. The bars represent average ratios + standard errors. The numbers by the bars represent the fold change in ADJ and TUM compared to DF tissues. *Statistical significance compared to DF tissues (p≤0.05). PDGF-A, platelet-derived growth factor-A; MIC-1, macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1; FASN, fatty acid synthase; EGR-1, early growth response-1; ROI, region of interest.

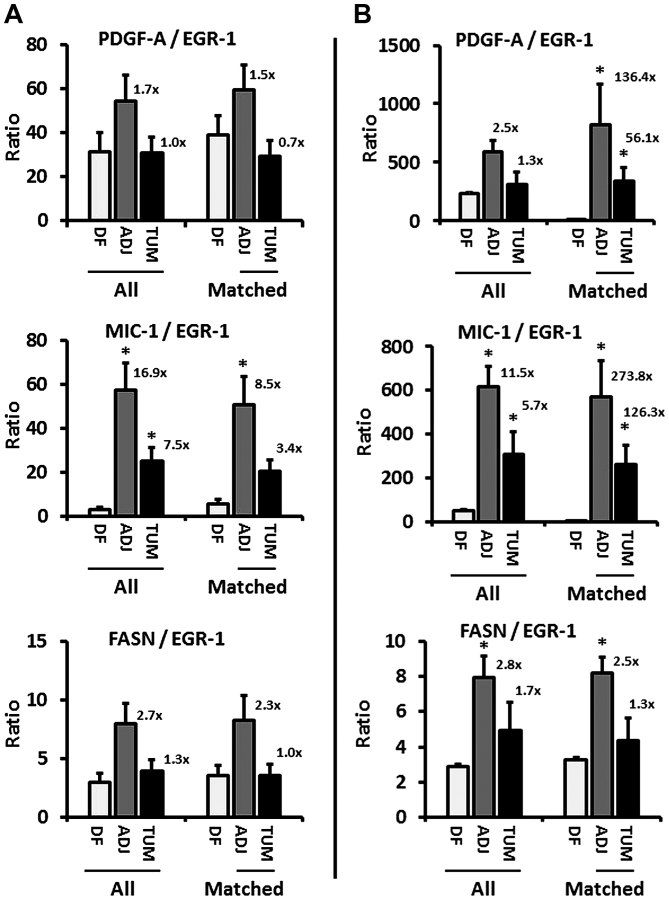

Figure 3.

(A and C) Graphical representation of Pearson's correlation (r) between EGR-1 and PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN using data from digitized images acquired by the whole-image and the ROI mode, respectively. Within each type of tissue, disease-free (DF), tumor-adjacent (ADJ), and tumor (TUM), correlations were determined for all matched, and for EGR-1 above or below the median with the corresponding median-divided datasets of PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN. (A) Datasets consist of whole-cell, nuclear, and cytoplasmic EGR-1 measurements (a total of 15 correlations per factor). (B) Datasets consist of nuclear and cytoplasmic EGR-1 measurements (a total of 12 correlations per factor). Arrows depict the change of regulation by linking the mean Pearson's correlations (black dots) in the different types of tissues. (B and D) Average positive (pos; black bars) and negative (neg; grey bars) Pearson's correlations between EGR-1 and PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN in DF, ADJ, and TUM tissues acquired by the whole-image and the ROI mode, respectively. The bars represent average ratios + standard errors. The numbers represent the fold change in the ratio of positive/negative r in ADJ and TUM compared to DF tissues. *Statistical significance compared to DF tissues (p≤0.05). EGR-1, early growth response-1; PDGF-A, platelet-derived growth factor-A; MIC-1, macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1; FASN, fatty acid synthase; ROI, region of interest.

Results

Immunofluorescence detection of EGR-1, PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN in human prostate tissues

We previously reported on the extent of the individual expression of EGR-1, PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN to support the concept of field effect in histologically normal prostate tissues adjacent to histologically overt adenocarcinomas, as compared to disease-free tissues (12,13). To begin unraveling the functional pathways of field effect in prostate tissues, here we analyzed the potential association between these markers of field effect in human prostate tissues of different histology. For this analysis, a total of 488 digitized images from 39 individual human prostate tissue samples was available for a comprehensive analysis (Table I). The images indicate the specific detection of EGR-1, PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN by immunofluorescence which was quantified computationally (12,13). Representative images are shown in Fig. 1A. In general, the expressions of EGR-1, PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN were highest in tumor and lowest or absent in disease-free tissues (Fig. 1A, panels i–iv and ix–xii, respectively). Furthermore, tumor-adjacent tissues tended to display elevated expression of all factors (Fig. 1A, panels v–viii). The specificity of detection was corroborated by the absent staining with isotype-specific control antibodies (Fig. 1A, panels xiii–xv).

Quantification and association analyses of EGR-1, PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN expressions in human prostate tissues

We have previously developed sensitive quantification methods for signals generated by immunofluorescence in human prostate tissues [(12,13) and the ‘Materials and methods’]. These methods include whole-image and ROI data acquisition modalities for all investigated factors (in the ‘Materials and methods’). Furthermore, in line with the aim of this study to be as comprehensive as possible with respect to associative analyses, EGR-1 expression was measured using three specific settings for cell compartmentalization: whole-cell, as well as nuclear and cytoplasmic separately. This is supported by an elegant study by Mora et al (14) who showed that EGR-1 can shuttle between these locations depending on cellular type and context. These different types of data acquisition are shown in Fig. 1B.

While our previous reports compared the level of expression for EGR-1, PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN in disease-free, tumor-adjacent, and tumor tissues, thereby supporting the concept of field effect (12,13), the primary objective of the present study was to explore a potential relationship between these factors and to determine whether that relationship changes in different types of tissues. As expected, and typical for human tissue studies, both the whole-image and the ROI data acquisition modes resulted in substantial heterogeneity with respect to variation of expression of all factors in disease-free, tumor-adjacent, and tumor tissues. The coefficient of variations ranged from 4.7 to 39.0% in the whole-image and from 3.9 to 31.1% in the ROI measurements.

Quantified expression data were comprehensively analyzed for similarities, discrepancies, and associations using straightforward, yet robust statistical methods. Of note, because of the expected inter- and intra-tissue heterogeneity, the identification of outliers was not meaningful and we adopted an inclusive approach in which we did not exclude any data points. In addition, due to different antibody affinities for their targets, we determined that comparisons of the mean, variance, and distribution of expression data between factors would not be good indicators of a causative regulatory role of EGR-1 for the other factors. In fact, group analysis by ANOVA indicated that all expression patterns in all types of tissues were distinct from each other (p<0.001), and individual comparisons by Wilcoxon rank-sum test were non-informative with respect to the distinction between induction and repression (p≤0.05) or coupled expression (p>0.05). Consequently, we chose to analyze the change of the ratio of either PDGF-A, MIC-1, or FASN to EGR-1 in disease-free compared to tumor-adjacent and tumor tissues. Based on our previous results showing that prostate tissues adjacent to adenocarcinomas feature a field effect compared to disease-free tissues (12,13), such a change in ratio would suggest a potential regulatory role of EGR-1 in agreement with its proven upregulation during tumorigenesis and cancer progression (16). Accordingly, EGR-1 expression determined by both the whole-image and ROI acquisition modes in all available tissues revealed an increase of all factors-to-EGR-1 ratios, up to 2.5-fold for PDGF-A, 16.9-fold for MIC-1, and 2.8-fold for FASN (Fig. 2A and B, left bar graphs). Similarly, when analyzed for matched adjacent and tumor tissues only (derived from the same patients, respectively), the ratio of the other factors to EGR-1 in both acquisition modes markedly increased, up to 136.4-fold for PDGF-A, 273.8-fold for MIC-1, and 2.5-fold for FASN (Fig. 2A and B, right bar graphs). While this analysis does not reveal the direction of regulation (positive or negative), the changes do indicate a regulatory function of EGR-1 for PDGF-A, MIC-1, and to a lesser extent for FASN.

The changes in the expression ratio of PDGF-A, MIC-1, and to some extent FASN, prompted us to refine our determination of a potential regulatory effect of EGR-1 on these factors by using Pearson's correlation analysis, which is independent of differences in antibody affinities for the different factors. By definition, this approach included tissues from matched cases only. To refine our analysis, we also separated all expression data by the median and determined the correlation between expression levels above and below median values. Similar to the ratio analysis presented in Fig. 2, we attempted to corroborate possible regulatory effects of EGR-1 for PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN expressions by comparing Pearson's correlations between different types of tissues, i.e., disease-free, tumor-adjacent, and tumor tissues. Fig. 3A and C shows a graphical representation of all possible correlations between whole-cell, nuclear, and cytoplasmic EGR-1 and PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN expression in disease-free, tumor-adjacent, and tumor tissues as acquired by whole-image and ROI acquisition mode, respectively. In contrast to group analyses by ANOVA or individual comparisons by Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Pearson's correlation analyses are indicators of positive vs. negative regulation. The significance (average p) of the Pearson's correlation coefficients for the whole-image acquisition mode was 0.16, 0.24, and 0.25 (with 40, 7 and 18% of all coefficients being p≤0.05) for PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN, respectively. For the ROI acquisition mode, the significance (average p) for the corresponding factors was 0.21, 0.21, and 0.25 (with 17, 23 and 7% of all coefficients being p≤0.05). Visual inspection of the Pearson's correlation analyses in Fig. 3A and C indicates that EGR-1 positively and negatively regulates PDGF-A and MIC-1, respectively, while the results for FASN regulation were less clear due to the contrasting data between the two data acquisition modes. Similar to the ratio analysis presented in Fig. 2, we attempted to corroborate possible regulatory effects of EGR-1 for PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN expressions by comparing Pearson's correlations between different types of tissues, i.e., disease-free, tumor-adjacent, and tumor tissues. Given the high tissue heterogeneity, we used an inclusive approach and compared the average of all positive and negative correlations (r>0 or <0) for each factor in the three types of tissues. This analysis showed a progressive positive and negative regulation of PDGF-A (up to 64.6-fold) and MIC-1 (up to 10-fold), respectively, in tumor-adjacent and tumor tissues compared to disease-free tissues. Again, results for FASN were less clear with contrasting results depending on the data acquisition mode (Fig. 3B and D). These possible regulations were confirmed by visually linking the means of Pearson's correlations in the different types of tissues (Fig. 3A and B).

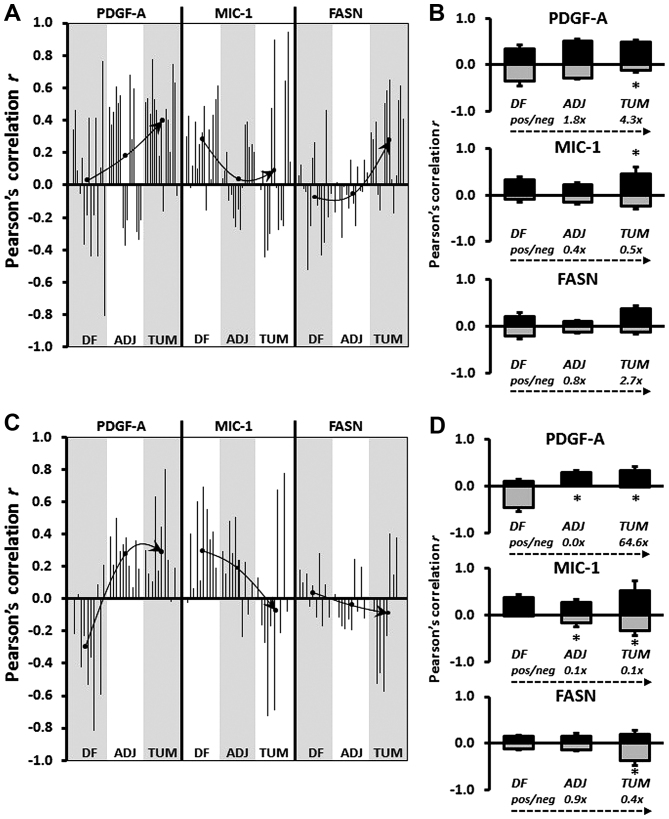

Computational and cell experimental analysis of EGR-1 regulation of PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN

The theoretical potential of the transcription factor EGR-1 to be a regulator of PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN expression was determined computationally using Tfsitescan software applied to 1,500 bp upstream and 500 bp downstream of the transcription initiation site on the genomic sequences of PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN. Thus, a total of 2,000 bp was screened for the presence of the EGR-1 recognition sequence [GCG(G/T)GGCG] (15). This analysis resulted in the identification of two, one, and four recognition sequences for PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN, respectively (Fig. 4A). Regulation of PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN expression by EGR-1 was experimentally tested by overexpression and suppression of EGR-1 in transient transfection experiments using the non-cancerous RWPE-1 human prostate epithelial cell model. The immortalized but non-cancerous RWPE-1 cells were chosen because they best represent the tissues analyzed in this study, which are almost exclusively early-stage malignancy and tumor-adjacent, i.e., best reflective of field effect. Transfections with the pcDNA3.1 and the pLKO.1 plasmids typically resulted in 50–100-fold overexpression and suppression of EGR-1 at the mRNA level (not shown). Modulation of EGR-1 protein expression was verified by western blotting and resulted in ~2-fold overexpression and suppression. Although the regulatory effects on PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN were rather small, transient EGR-1 overexpression upregulated PDGF-A and FASN protein expression (up to 2-fold) and downregulated MIC-1 protein expression (up to 3-fold), while transient EGR-1 suppression corroborated this effect by upregulating MIC-1 protein expression (~1.5-fold), while downregulating PDGF-A and FASN protein expression (up to 2-fold) (Fig. 4B). These results were accompanied by similar changes at the mRNA level, as measured by qRT-PCR. Accordingly, transient EGR-1 overexpression upregulated PDGF-A and FASN (up to 2-fold) and downregulated MIC-1 (up to 2-fold), while transient EGR-1 suppression corroborated this effect by downregulating PDGF-A and FASN (up to 2.5- and 5-fold, respectively) and by upregulating MIC-1 (up to 10-fold) (Fig. 4C). Overall, these results are in good agreement with the observations made in the tissues.

Figure 4.

(A) Computational analysis of the EGR-1 recognition sequence [GCG(G/T)GGCG] in the genomic sequence 1,500 bp upstream and 500 bp downstream of the transcription initiation site of PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN. Black vertical lines and black rectangular boxes denote genomic sequences and exons, respectively; vertical arrow heads indicate EGR-1 recognition sequences. (B) EGR-1, PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN protein expression in RWPE-1 cells transiently transfected with pcDNA3.1/EGR-1 (EGR-1 overexpression) or pLKO.1/EGR-1 shRNA (EGR-1 suppression), and their empty plasmid controls. Double bands in EGR-1 represent post-translational modifications (44). The fold change difference compared to empty plasmid control and determined by densitometry as a ratio with β-actin signal is indicated in the small bar graphs (left bar, EGR-1 overexpression; right bar, EGR-1 suppression). (C) Relative mRNA expression of PDGF-A, MIC-1, and FASN in RWPE-1 cells transiently transfected with pcDNA3.1/EGR-1 (EGR-1 overexpression) or pLKO.1/EGR-1 shRNA (EGR-1 suppression), and their empty plasmid controls. Bars represent averages of triplicates ± standard deviation; *Statistical significance (p≤0.05) from pcDNA3.1 and pLKO.1 plasmid vector control, respectively. EGR-1, early growth response-1; PDGF-A, platelet-derived growth factor-A; MIC-1, macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1; FASN, fatty acid synthase.

Discussion

The importance of field effect, or field cancerization, in the prostate has been well-recognized as worthy of being explored in detail for the benefit of developing clinical applications towards a better clinical management of prostate cancer (8–10,17). For example, we have previously argued that prostate field effect could be used to improve the diagnosis of prostate cancer in false-negative biopsies (10). The latter remains an important and continuous challenge in confirmatory diagnosis of prostate adenocarcinoma that has clinical, psychological, and financial implications (18–21). Accordingly, field-cancerized tissue could increase the clinically informative area that can be analyzed microscopically by a surgical pathologist if histology could be combined with immunological techniques. In this scenario, the pathologist would recognize the presence and location of a lesion even in the absence of its visual confirmation thereby avoiding false-negative cells, even after repeated biopsies (22). This possibility has prompted others to term tissues affected by field-effect tumor-indicating normal tissue (TINT) (8). Even in the case of a positive identification of cancer, the extent (number of positive biopsy cores, % of tissue affected) and the grade (Gleason) may indicate a low risk for progression and thus eligibility for active surveillance with frequent testing for serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA), as opposed to prostatectomy (23). It is conceivable that during active surveillance, a recognized field effect could be monitored and queried as an indicator of potential progression (10,24). This would help mitigate the well-known overtreatment of prostate cancer with surgery, which albeit performed with curative intent, may unnecessarily decrease quality of life due to its severe side-effects (25,26). The latter approach could also be amenable to the assessment of pre-surgical neo-adjuvant therapeutic interventions, for which the efficacy could be monitored during active surveillance by established markers and parameters of field effect (10,27). A further potential application of field effect lies in its inclusion in the definition of surgical margins for focal therapy, which seems to be on the rise as a form of less invasive therapy and as more refined interventions have developed (10,28,29). As such, the presence of a field effect at the margin may be indicative of elevated risk for progression or of the extent of tumor multifocality within the prostate (10,30). Of note, the common assumption underlying the aforementioned potential applications of prostate field effect is that a field exists as a consequence of the presence of a lesion. However, it is also conceivable that field effect precedes tumor formation and represents a truly pre-malignant status evident at the molecular level but in absence of any histological change. In fact, the latter view is widely accepted (8–10,17) and defines field-cancerized prostate tissues as a temporal record of tumorigenesis. As such, it is a source for early biomarkers and potential targets for preventative strategies (8,10).

Pertinent to all applications of field effect is the knowledge of the molecular markers and pathways that are characteristic for it. We and others have previously compiled lists of molecular markers reported in the scientific literature (7–10), but for most of these factors the etiology remains unknown. For markers of field effect to be of best use, either as indicators or as targets, it is important to begin identifying distinct cellular and molecular events and pathways that underlie the formation of a field. Towards this goal, in this report we have established a link between four protein factors of prostate field effect, which were originally identified individually or deduced from the literature. We had identified the key transcription factor EGR-1, the divergent member of the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) MIC-1, and the lipogenic oncogene FASN as being elevated in prostate tissues 1 cm from the visible tumor margin (11). While our original study was microarray-based and thus RNA-specific, we subsequently confirmed EGR-1, MIC-1, FASN, and PDGF-A protein upregulation in field-cancerized human prostate tissues (12,13).

EGR-1 is a central regulator of many molecular pathways and acts divergently according to the cell context (31). While in other types of tissues, it may function primarily as a tumor suppressor, it ultimately assumes, with some ambiguity, a tumor-promoting role in prostate cancer development and progression (16,32,33). The role of the secreted factor PDGF-A in prostate cancer is well-established. It is one of four isoforms that binds as a dimer to the tyrosine kinase receptors PDGFRα and β. PDGF-A stimulates growth, survival, and motility of various cell types and when hyperactivated, promotes prostate cancer development and progression through paracrine and autocrine actions (34,35). Equally established in prostate cancer development and progression is FASN, which has been termed a metabolic oncogene and is the target of ongoing efforts to develop specific inhibitors of its lipogenic activity promoting tumor cell proliferation through lipid biosynthesis and post-translational protein modification (36,37). The role of MIC-1 is less clear and is reported as both a cancer promoter and suppressor (38,39). Originally discovered in macrophages (40), it may promote a pro-tumorigenic environment when secreted by prostate cancer cells by suppressing the anticancer activity of immune cells (41).

It is conceivable that the concerted actions of MIC-1, PDGF-A, and FASN can lead to the formation of molecularly altered fields through autocrine stimulation of hyperproliferative cell foci prone to further genetic and biochemical change towards transformation, which is congruent with the definition of a pre-malignant field effect. However, the possibility of cross-regulatory influences of these actions remain unknown. Since EGR-1 is a pleiotropic transcription factor, we hypothesized that it could regulate MIC-1, PDGF-A, and FASN. The present study aimed at testing this possibility through comprehensive association analyses using quantitative immunofluorescence expression data generated in human prostate tissues. EGR-1 has been previously shown to induce many target genes, including PDGF-A in the LAPC4 cell model of prostate cancer after ectopic overexpression of EGR-1 (42). Similarly, MIC-1 seems to be positively regulated by EGR-1 in the LNCaP prostate cancer cell model (43). In contrast, there is a lack of information for a potential regulatory function of EGR-1 for FASN in prostate cells or tissues, although our computational analysis of genomic DNA up- and downstream of the transcription initiation site indicates multiple EGR-1 recognition sequences. Our own ectopic EGR-1 overexpression and suppression data in RWPE-1 cells confirms a positive regulation of PDGF-A, but resulted in a negative regulation of MIC-1. An obvious reason for this discrepancy is that RWPE-1 represents a non-cancerous pre-malignant, as opposed to an advanced cancer cell model, such as LNCaP (43). At the experimental level, the use of reporter constructs for MIC-1 activity (43) vs. qRT-PCR using specific primers may also have contributed to differences in the result. More importantly however, our in vitro findings are supported by our extensive in situ association studies in human tissues which are based on factor correlations and their changes from disease-free to tumor-adjacent to histologically abnormal tissues, thereby confirming the presence of a field effect. In fact, using two data acquisition modes our data show a positive association between EGR-1 and both PDGF-A and FASN, which in turn support a positive regulation. In contrast, our results suggest a negative regulation of MIC-1 by EGR-1, which seemingly contradicts our observation that both are upregulated in tumor-adjacent and cancerous prostate tissues when compared to disease-free controls (12). While the latter justifies the inclusion of MIC-1 in the present study, this discrepancy indicates a more complex regulatory network and warrants further investigations using functional approaches in systems that reflect the complexity of human tissues.

In summary, three principal conclusions can be drawn from our findings. First, immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence are techniques usually employed towards qualitative assessment of protein expression and localization in cells and tissues in a static manner. However, we show here that using sophisticated quantitation methods, such as spectral image acquisition, linear unmixing, and digital imaging developed in our previous reports (12,13), can deliver meaningful indications of molecular associations in a physiologically relevant in situ environment, even in the presence of high heterogeneity. A related issue is the use of ROIs in quantitation. ROIs are often used to compensate for inequalities of cell composition. Although our data show good congruency between the whole-image and ROI approaches for the most part, it also cautions for care with respect to the number of ROIs and their random and blinded placement. Second, our study prompts for caution when comparing molecular association data generated in cell models with data stemming from tissues. Although it can be argued that tissue studies are static and compromised by sample heterogeneity, they can provide meaningful indications of molecular regulations when coupled with sophisticated data acquisition. Also, tissues are physiologically relevant, reflect better the complexity of cellular and molecular pathways influenced by the environment, and can guide confirmatory studies in cell models. Third, we propose EGR-1 to be a key regulator of prostate field effect through induction of pro-proliferative and pro-metabolic (PDGF-A and FASN, respectively) and suppression of pro-apoptotic (MIC-1) factors. This is supported in particular by our comparative data between disease-free and tumor-adjacent tissues (field effect). Admittedly, while the positive regulation of PDGF-A and FASN by EGR-1 can be easily acknowledged, its regulatory function for MIC-1 seems less clear due to its concomitant upregulation in tumor-adjacent tissues (13). However, it is important to note that these findings are not in disagreement, as MIC-1 regulation has been discussed to be complex (38,39). This may be reflected in a complex in situ environment, such as tissues, where many other factors may also exert their regulatory effect. Future studies are warranted to test the exact mechanisms of direct and/or indirect regulation under physiological conditions, such as in animal models. Because it is widely accepted that field effect represents a pre-malignant state, such knowledge may help develop targeted intervention strategies preventing progression to cancer.

Acknowledgements

We thank the following individuals at the New Mexico Health Sciences Center, Department of Pathology and Hospital: Trisha Fleet for procuring prostate tissues through patient consent; Myra Zucker, Cathy Martinez, and Kari Rigg for skillfully preparing prostate tissue sections; the surgical pathologist Dr E.G. Fischer for the histological review of all prostate tissues utilized in this study. We acknowledge Kerry Wiles from the CHTN-Western Division at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (Nashville, TN, USA) for the successful procurement of prostate tissues and annotated reports. We are grateful to Genevieve Phillips and Dr Rebecca Lee from the University of New Mexico and Cancer Center, Fluorescence Microscopy Shared Resource for excellence assistance and technical input for generating the images by spectral imaging and linear unmixing. We thank Ms. Virginia Severns, Ms. Fiona Bisoffi, and Ms. Suzanne Jones for the unbiased placing of the ROI boxes for signal quantitation in the tissue images. The departmental offices and staff of the University of New Mexico, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Office of Medical Student Affairs, and the Schmid College of Science and Technology, Chapman University are acknowledged for administrative support. This study was supported by NIH grant RR0164880, NIH grant R03CA136030-02, Prostate Cancer Research Program grant W81XWH-15-1-0056 from the Department of Defense (to Dr M. Bisoffi), University of New Mexico Cancer Center Support grant NIH/NCI P30CA118110, grants from the Chapman University Office of Undergraduate Research (to Miss K. Gabriel and Miss E. Frisch), and a generous gift from Melinda and Edward Subia of Orange County, CA, USA.

Abbreviations

- EGR-1

early growth response-1

- FASN

fatty acid synthase

- MIC-1

macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1

- PDGF-A

platelet-derived growth factor-A

References

- 1.Epstein JI. Mimickers of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Int J Surg Pathol. 2010;18(Suppl):142S–148S. doi: 10.1177/1066896910370616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montironi R, Mazzucchelli R, Algaba F, Lopez-Beltran A. Morphological identification of the patterns of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and their importance. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:655–665. doi: 10.1136/jcp.53.9.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Marzo AM, Platz EA, Sutcliffe S, Xu J, Grönberg H, Drake CG, Nakai Y, Isaacs WB, Nelson WG. Inflammation in prostate carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:256–269. doi: 10.1038/nrc2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Marzo AM, Marchi VL, Epstein JI, Nelson WG. Proliferative inflammatory atrophy of the prostate: Implications for prostatic carcinogenesis. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:1985–1992. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65517-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W. Field cancerization in oral stratified squamous epithelium; clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer. 1953;6:963–968. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195309)6:5<963::AID-CNCR2820060515>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braakhuis BJ, Tabor MP, Kummer JA, Leemans CR, Brakenhoff RH. A genetic explanation of Slaughter's concept of field cancerization: Evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1727–1730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dakubo GD, Jakupciak JP, Birch-Machin MA, Parr RL. Clinical implications and utility of field cancerization. Cancer Cell Int. 2007;7:2. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halin S, Hammarsten P, Adamo H, Wikström P, Bergh A. Tumor indicating normal tissue could be a new source of diagnostic and prognostic markers for prostate cancer. Expert Opin Med Diagn. 2011;5:37–47. doi: 10.1517/17530059.2011.540009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nonn L, Ananthanarayanan V, Gann PH. Evidence for field cancerization of the prostate. Prostate. 2009;69:1470–1479. doi: 10.1002/pros.20983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trujillo KA, Jones AC, Griffith JK, Bisoffi M. Markers of field cancerization: Proposed clinical applications in prostate biopsies. Prostate Cancer. 2012;2012:302894. doi: 10.1155/2012/302894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haaland CM, Heaphy CM, Butler KS, Fischer EG, Griffith JK, Bisoffi M. Differential gene expression in tumor adjacent histologically normal prostatic tissue indicates field cancerization. Int J Oncol. 2009;35:537–546. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones AC, Antillon KS, Jenkins SM, Janos SN, Overton HN, Shoshan DS, Fischer EG, Trujillo KA, Bisoffi M. Prostate field cancerization: Deregulated expression of macrophage inhibitory cytokine 1 (MIC-1) and platelet derived growth factor A (PDGF-A) in tumor adjacent tissue. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones AC, Trujillo KA, Phillips GK, Fleet TM, Murton JK, Severns V, Shah SK, Davis MS, Smith AY, Griffith JK, et al. Early growth response 1 and fatty acid synthase expression is altered in tumor adjacent prostate tissue and indicates field cancerization. Prostate. 2012;72:1159–1170. doi: 10.1002/pros.22465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mora GR, Olivier KR, Cheville JC, Mitchell RF, Jr, Lingle WL, Tindall DJ. The cytoskeleton differentially localizes the early growth response gene-1 protein in cancer and benign cells of the prostate. Mol Cancer Res. 2004;2:115–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pagel JI, Deindl E. Disease progression mediated by egr-1 associated signaling in response to oxidative stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:13104–13117. doi: 10.3390/ijms131013104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gitenay D, Baron VT. Is EGR1 a potential target for prostate cancer therapy? Future Oncol. 2009;5:993–1003. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walia G, Pienta KJ, Simons JW, Soule HR. The 19th annual Prostate Cancer Foundation scientific retreat. Cancer Res. 2013;73:4988–4991. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delongchamps NB, Haas GP. Saturation biopsies for prostate cancer: Current uses and future prospects. Nat Rev Urol. 2009;6:645–652. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2009.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eichler K, Hempel S, Wilby J, Myers L, Bachmann LM, Kleijnen J. Diagnostic value of systematic biopsy methods in the investigation of prostate cancer: A systematic review. J Urol. 2006;175:1605–1612. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00957-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Presti JC., Jr Prostate biopsy strategies. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2007;4:505–511. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro0887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rabbani F, Stroumbakis N, Kava BR, Cookson MS, Fair WR. Incidence and clinical significance of false-negative sextant prostate biopsies. J Urol. 1998;159:1247–1250. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)63574-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel AR, Jones JS. Optimal biopsy strategies for the diagnosis and staging of prostate cancer. Curr Opin Urol. 2009;19:232–237. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e328329a33e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pomerantz M. Active surveillance: Pathologic and clinical variables associated with outcome. Surg Pathol Clin. 2015;8:581–585. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mazzucchelli R, Galosi AB, Santoni M, Lopez-Beltran A, Scarpelli M, Cheng L, Montironi R. Role of the pathologist in active surveillance for prostate cancer. Anal Quant Cytopathol Histpathol. 2015;37:65–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bellardita L, Valdagni R, van den Bergh R, Randsdorp H, Repetto C, Venderbos LD, Lane JA, Korfage IJ. How does active surveillance for prostate cancer affect quality of life? A systematic review. Eur Urol. 2015;67:637–645. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwon O, Hong S. Active surveillance and surgery in localized prostate cancer. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 2014;66:175–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lou DY, Fong L. Neoadjuvant therapy for localized prostate cancer: Examining mechanism of action and efficacy within the tumor. Urol Oncol. 2016;34:182–192. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindner U, Lawrentschuk N, Schatloff O, Trachtenberg J, Lindner A. Evolution from active surveillance to focal therapy in the management of prostate cancer. Future Oncol. 2011;7:775–787. doi: 10.2217/fon.11.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marshall S, Taneja S. Focal therapy for prostate cancer: The current status. Prostate Int. 2015;3:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.prnil.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andreoiu M, Cheng L. Multifocal prostate cancer: Biologic, prognostic, and therapeutic implications. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:781–793. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pagel JI, Deindl E. Early growth response 1 - a transcription factor in the crossfire of signal transduction cascades. Indian J Biochem Biophys. 2011;48:226–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adamson E, de Belle I, Mittal S, Wang Y, Hayakawa J, Korkmaz K, O'Hagan D, McClelland M, Mercola D. Egr1 signaling in prostate cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2003;2:617–622. doi: 10.4161/cbt.2.6.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adamson ED, Mercola D. Egr1 transcription factor: Multiple roles in prostate tumor cell growth and survival. Tumour Biol. 2002;23:93–102. doi: 10.1159/000059711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heldin CH. Autocrine PDGF stimulation in malignancies. Ups J Med Sci. 2012;117:83–91. doi: 10.3109/03009734.2012.658119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heldin CH. Targeting the PDGF signaling pathway in tumor treatment. Cell Commun Signal. 2013;11:97. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-11-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baron A, Migita T, Tang D, Loda M. Fatty acid synthase: A metabolic oncogene in prostate cancer? J Cell Biochem. 2004;91:47–53. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zadra G, Photopoulos C, Loda M. The fat side of prostate cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 18312013:1518–1532. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Husaini Y, Qiu MR, Lockwood GP, Luo XW, Shang P, Kuffner T, Tsai VW, Jiang L, Russell PJ, Brown DA, et al. Macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 (MIC-1/GDF15) slows cancer development but increases metastases in TRAMP prostate cancer prone mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vaňhara P, Hampl A, Kozubík A, Souček K. Growth/differentiation factor-15: Prostate cancer suppressor or promoter? Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2012;15:320–328. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2012.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bootcov MR, Bauskin AR, Valenzuela SM, Moore AG, Bansal M, He XY, Zhang HP, Donnellan M, Mahler S, Pryor K, et al. MIC-1, a novel macrophage inhibitory cytokine, is a divergent member of the TGF-beta superfamily. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11514–11519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karan D, Holzbeierlein J, Thrasher JB. Macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1: Possible bridge molecule of inflammation and prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Svaren J, Ehrig T, Abdulkadir SA, Ehrengruber MU, Watson MA, Milbrandt J. EGR1 target genes in prostate carcinoma cells identified by microarray analysis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38524–38531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005220200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shim M, Eling TE. Protein kinase C-dependent regulation of NAG-1/placental bone morphogenic protein/MIC-1 expression in LNCaP prostate carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18636–18642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414613200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mora GR, Olivier KR, Mitchell RF, Jr, Jenkins RB, Tindall DJ. Regulation of expression of the early growth response gene-1 (EGR-1) in malignant and benign cells of the prostate. Prostate. 2005;63:198–207. doi: 10.1002/pros.20153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]