ABSTRACT

The latent infection of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is associated with 1% of human cancer incidence. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation (PARylation) is a posttranslational modification catalyzed by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs) that mediate EBV replication during latency. In this study, we detail the mechanisms that drive cellular PARylation during latent EBV infection and the effects of PARylation on host gene expression and cellular function. EBV-infected B cells had higher PAR levels than EBV-negative B cells. Moreover, cellular PAR levels were up to 2-fold greater in type III than type I latently infected EBV B cells. We identified a positive association between expression of the EBV genome-encoded latency membrane protein 1 (LMP1) and PAR levels that was dependent upon PARP1. PARP1 regulates gene expression by numerous mechanisms, including modifying chromatin structure and altering the function of chromatin-modifying enzymes. Since LMP1 is essential in establishing EBV latency and promoting tumorigenesis, we explored the model that disruption in cellular PARylation, driven by LMP1 expression, subsequently promotes epigenetic alterations to elicit changes in host gene expression. PARP1 inhibition resulted in the accumulation of the repressive histone mark H3K27me3 at a subset of LMP1-regulated genes. Inhibition of PARP1, or abrogation of PARP1 expression, also suppressed the expression of LMP1-activated genes and LMP1-mediated cellular transformation, demonstrating an essential role for PARP1 activity in LMP1-induced gene expression and cellular transformation associated with LMP1. In summary, we identified a novel mechanism by which LMP1 drives expression of host tumor-promoting genes by blocking generation of the inhibitory histone modification H3K27me3 through PARP1 activation.

IMPORTANCE EBV is causally linked to several malignancies and is responsible for 1% of cancer incidence worldwide. The EBV-encoded protein LMP1 is essential for promoting viral tumorigenesis by aberrant activation of several well-known intracellular signaling pathways. We have identified and defined an additional novel molecular mechanism by which LMP1 regulates the expression of tumor-promoting host genes. We found that LMP1 activates the cellular protein PARP1, leading to a decrease in a repressive histone modification, accompanied by induction in expression of multiple cancer-related genes. PARP1 inhibition or depletion led to a decrease in LMP1-induced cellular transformation. Therefore, targeting PARP1 activity may be an effective treatment for EBV-associated malignancies.

INTRODUCTION

The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a human gammaherpesvirus that latently infects approximately 95% of the population worldwide (1). Latent EBV infection contributes to 1% of human cancers, including Burkitt's lymphoma and nasopharyngeal carcinoma (2, 3). To establish a latent infection in a naive B cell, EBV first adopts a type III latent gene expression program in which all latency genes are expressed to provide intracellular signals to the infected B cell that mimic antigenic stimulation, driving proliferation and differentiation (4, 5). Because expression of this large set of EBV genes is highly immunogenic, the virus eventually adopts a more restricted gene expression profile, referred to as a type I latent gene expression program (3, 6). In type I latency, EBNA1 is the only protein expressed, allowing the EBV-infected host cell to evade detection by the immune system (7). Different latency types correlate with specific EBV-associated malignancies (3, 6). Thus, understanding EBV gene regulation during latency and the molecular mechanisms that control EBV latency switching will provide crucial new insights into the development of EBV-associated malignancies and will promote the development of novel treatments for a leading cause of cancer on a global scale.

The host cell regulates EBV gene expression during latency through several epigenetic mechanisms, including histone modifications, DNA methylation, and long-range chromatin interactions (8, 9). However, alterations in epigenetic regulation during EBV latency may also be attributed to disruptions induced directly by the virus. Since EBV does not integrate into the host genome, the virus may hijack the host epigenetic machinery as the primary means to differentially regulate its own gene expression profile during latency. If so, the disruptions in epigenetic regulation that control latent viral infection may also have significant secondary effects on host gene expression.

Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation (PARylation) is a posttranslational modification mediated by a group of enzymes called poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs) (10). The reaction generates long, negatively charged ADP-ribose polymers that are covalently bound to target proteins, including histones (11, 12). PARylation of histones reduces their affinity for DNA due to electrostatic repulsion (13), creating a more relaxed, or decondensed, chromatin structure which makes the DNA more accessible to DNA repair or transcriptional machineries (13–15). Additionally, the PARP1 protein plays an important regulatory role in gene expression, mainly promoting transcriptional activation through epigenetic mechanisms (13, 16–18). The host also uses PARylation, specifically through the PARP1 protein, to regulate both the lytic and latent infection of EBV (19, 20).

While the host uses PARylation to regulate the virus, it is unknown if the opposite is true, whether the viral gene products can influence PARylation, and if disruption of PARP regulation is sufficient to alter host gene expression. In the present study, we explored the relationship between EBV latency type and PARylation and determined that type III cells latently infected with EBV have significantly higher PAR levels than type I latently infected EBV cells. Expression of the type III latency-associated EBV protein LMP1 alone was sufficient to promote PARP1-mediated PARylation. The inhibition of PARylation contributed to alterations in the host epigenome, which resulted in a reduction of the repressive histone mark H3K27me3 and induced the expression of two established LMP1 target proto-oncogenes, c-Fos and EGR1. Moreover, PARP1 contributed to LMP1-mediated cellular transformation. Taken together, we have identified a novel mechanism for LMP1 in driving the expression of tumor-promoting genes in the host by blocking the incorporation of an inhibitory epigenetic modification through the activation of PARP1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and drug treatment.

All cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere in medium containing antibiotics. B cell lines were cultured in suspension in RPMI 1640 supplemented with fetal bovine serum at a concentration of 10% (Akata lines, Mutu I, Kem I, and Daudi) or 15% (DG75, lymphoblastoid cell lines [LCLs], Kem III, Raji, GM12878, and GM13605). Murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (wild type [WT] and PARP1−/−), kind gifts from Zhao-Qi Wang (21), and Rat1 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum. Olaparib (Selleck Chemical) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and cells were treated for 72 h upon dilution in the appropriate media. Cell viability was assessed using the CellTiter Glo luminescent cell viability assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Determination of total cellular PAR.

Cellular poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) levels were quantified using a PARP in vivo pharmacodynamic assay 2nd generation (PDA II) kit (Trevigen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 2 × 106 cells were lysed in the supplied buffer, and protein concentration was determined with a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay (Pierce). Cell extracts were added to a precoated capture antibody plate, incubated overnight at 4°C, and washed four times with phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST). A polyclonal antibody for the detection of PAR was added, and the plate was incubated at room temperature for 2 h. After washing four times with PBST, goat anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was added, and the plate was incubated for 1 h. The wells were washed four times with PBST. The PARP PeroxyGlow reagent was added, and luminescence was measured using a POLARstar Optima microplate reader (BMG Labtech).

Western blot analysis.

Cell lysates were prepared in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.25% deoxycholic acid, 1% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific). Soluble extracts were recovered by centrifugation at 21,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and protein concentration was determined with the BCA protein assay (Pierce). Lysates were boiled in 2× SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing 2.5% β-mercaptoethanol, resolved on a 4 to 20% polyacrylamide gradient Mini-Protean TGX precast gel (Bio-Rad), and transferred to an Immobilon-P membrane. Membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature and incubated overnight with primary antibodies recognizing EBNA1 (Millipore), EBNA2 (Abcam), LMP1 (Abcam), PARP1 (Active Motif), PARP2 (Abcam), Actin (Sigma), H3K27me3 (Active Motif), and H3 (Abcam), as recommended the manufacturer. Membranes were washed, incubated for 1 h with the appropriate secondary antibody, either goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (Santa Cruz) or rabbit anti-mouse IgG-HRP (Thermo Scientific), washed, and detected by enhanced chemiluminescence.

Plasmids and transfections.

The plasmid vector pLXSN and the LMP1 expression construct pLXSN-LMP1 were provided by Rona Scott (LSU, Shreveport, LA). The Flag and Flag-EBNA1 vectors were kind gifts from Paul M. Lieberman (The Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, PA). The full-length cDNA plasmid constructs encoding human PARP1 WT and catalytically inactive PARP1 (E998A) were provided by John Pascal (Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA) and described previously (22, 23).

Nucleofection of DG75 cells.

Cells were transfected using an SF cell line 4D-Nucleofector kit (Lonza). Briefly, 5 × 106 cells were spun down at 100 × g for 10 min, the supernatant was removed, and the cell pellet was resuspended in 100 μl nucleofection solution containing 4 μg of pLXSN or pLXSN-LMP1. The solution was transferred to a Nucleocuvette, transfected using the EN-150 program on a Lonza 4D-Nucleofector, and the reaction mixture was incubated for 10 min at room temperature. Fresh, prewarmed medium (400 μl) was added to the Nucleocuvette, and the Nucleocuvette was incubated at 37°C for 90 min before transferring the solution to a single well in a 12-well plate. The 12-well plate was incubated at 37°C for 72 h before collection.

Transfection of Rat1, MEF, or MEF PARP1−/− cells with Lipofectamine.

A total of 2.5 × 105 cells/well were seeded in six-well dishes 1 day prior to transfection. Transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) with 2.5 μg DNA and 12 μl of Lipofectamine according to the manufacturer's instructions and incubated for 72 h at 37°C.

shRNA-mediated knockdown.

Plasmids carrying short hairpin RNA (shRNA) specific for PARP1 (shPARP1) or LMP1 (shLMP1) were generated by PCR and cloned into the pLKO.1-TCR cloning vector (24). pLKO.1-TRC was a gift from David Root (plasmid number 10878; Addgene). The pLKO.1-shPARP1 and pLKO.1-shLMP1 lentivirus expression vectors were generated according to the protocol provided by Addgene. Scrambled shRNA was a gift from David Sabatini (plasmid number 1864; Addgene) (25). shPARP1 and sh-non-effective scrambled for Rat1 cells were bought from Origene (TL709663 and TR30021). Lentiviral particles were generated by transfecting 293T cells with pLKO.1-shPARP1, shLMP1, or scrambled shRNA, the psPAX2 (plasmid number 12260; Addgene) packaging plasmid, and the pMD2.G envelope plasmid (plasmid number 12259; Addgene) according to the Addgene protocol. psPAX2 and pMD2.G plasmids were a gift from Didier Trono (plasmid numbers 12260 and 12259; Addgene). LCL, GM13605, Raji, or Rat1 cells were infected with lentivirus expressing a pool of four pLKO.1-LMP1 constructs, pLKO.1-PARP1, or the pLKO control vector freshly generated from 293T cells. Infected cells were then selected with 1 μg/ml puromycin for 3 days. The selected cells were pooled and used for further analysis. Oligodeoxynucleotide sequences are available upon request.

Retroviral transduction.

Plasmid constructs hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged full-length LMP1, pBABE, pVSV-G, and pGag/Pol were kindly provided by Nancy Raab-Traub (UNC, Chapel Hill, NC) and were described previously (26). Retroviral particles were generated using the Fugene 6 reagent (Promega) to simultaneously transfect subconfluent monolayers of 293T cells with 1 μg pBABE (vector) or HA-LMP1, 250 ng pVSV-G, and 750 ng pGal/Pol according to the manufacturer's instructions. After overnight incubation at 37°C the transfection medium was replaced with fresh medium, and cells were incubated at 37°C overnight. The medium containing retrovirus was harvested, filtered through a 0.45-μm filter, and stored at 4°C. Fresh medium was added to 293T cells, incubated overnight at 37°C, and collected and filtered as described above. The viral medium stocks collected at the two posttransfection time points were pooled and used for retroviral transduction. Rat1, MEF, or MEF PARP1−/− cells were transduced by seeding 5 × 105 cells in 6-well plates in 500 μl medium and adding 500 μl of medium containing retroviral particles. The transduced cells were harvested after 72 h and selected in 100-mm cell plates for 14 days in medium containing 5 μg/ml puromycin.

Extraction of histones.

Histones were extracted using a histone purification minikit (Active Motif) by following the manufacturer's recommendations. Briefly, cell pellets were resuspended in ice-cold histone extraction buffer and incubated overnight at 4°C. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 21,000 × g and 4°C for 5 min. The supernatant containing crude histones was neutralized with 5× neutralization buffer and transferred to the spin column supplied to the kit to bind histones. The column was washed three times, and histones were eluted. Purified histones were quantified using a Pierce BCA protein assay kit.

Quantitation of H3K27me3 by ELISA.

H3K27me3 levels were quantified using a histone H3 methylated Lys27 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Active Motif) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, histone extracts were added to the histone H3 antibody-coated plate, and the plate was incubated for 1 h at room temperature with agitation on a platform rocker. The wells were washed three times with wash buffer, the H3K27me3-specific primary antibody was added, and the plate was incubated at room temperature for 1 h with agitation. The wells were washed and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with an HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody. Following three washes, the developing solution was added for 2 min and the reaction was terminated with stop solution. The plate was read at 450 nm using a VERSAmax tunable microplate reader (Molecular Devices).

ChIP assay.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed according to the protocol provided by Upstate Biotechnology, Inc., with minor modifications as previously described (27, 28) and as follows. Cells were fixed in 1% formaldehyde for 15 min, and DNA was sonicated using a sonic dismembrator (Fisher Scientific) to generate 200- to 300-bp DNA fragments. Real-time PCR was performed with SYBR green on an ABI StepOnePlus PCR system using 1/100 of the ChIP DNA. Chromatin was immunoprecipitated with a polyclonal antibody to H3K27me3 (Active Motif). The primer sequences are available upon request.

RNA extraction and reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

RNA was extracted from 5 × 106 cells using a Qiagen RNA extraction kit according to the manufacturer's protocol. Super Script II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) was used to generate randomly primed cDNA from 2 μg of total RNA. A 50-ng sample of cDNA was analyzed by real-time PCR, using the ΔΔCT method on an ABI StepOnePlus machine. Primer sequences are available upon request.

Focus formation assay.

Rat1 cells transduced with pBABE or HA-LMP1 retrovirus expression vectors as described above were used for focus formation assays. Two weeks after transfection, 1 × 104 cells were seeded in 6-well plates and incubated with medium containing 5 μg/ml puromycin and 1.25 μM olaparib, 2.5 μM olaparib, or DMSO (1:1,000). After 72 h the olaparib or DMSO-containing medium was replaced with fresh medium containing 5 μg/ml puromycin, and the cells were grown for 14 days to allow focus formation. The cells were washed with PBS, fixed in methanol for 10 min, and stained with 1% crystal violet in 50% ethanol for 5 min to visualize foci. The plates were scanned and analyzed by the ImageJ plugin ColonyArea to quantify focus formation.

Microscopy.

Photomicrographs were taken of phase contrast and green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence of Rat-1 cells stably expressing LMP1 transduced with shControl or shPARP1 lentiviral particles. Images were acquired with an Envos FL cell imaging system using a 20× objective.

Statistical analysis.

All experiments presented were conducted at least in triplicate to ensure reproducibility of results. The Prism statistical software package (GraphPad) was used to identify statistically significant differences between experimental conditions and control samples using Student's t test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni's post hoc comparison test, as indicated in the figure legends.

RESULTS

Type III latency correlates with increased PAR levels.

To assess the relationship between EBV latency and the posttranslational modification PARylation, PAR levels were measured by ELISA in a panel of EBV-positive and EBV-negative B cell lines. The levels of cellular PAR in all of the EBV-positive cells exceed those in the EBV-negative cell lines Akata and DG75 (Fig. 1A). Moreover, there was a clear relationship between PAR levels and latency type in the EBV-positive cell lines. The type III latency cells LCL, Kem III, GM12878, and GM13605 had 3- to 4-fold higher PAR levels than type I latency cells Mutu I, Kem I, Akata, and the Wp-restricted latency Daudi cells (Fig. 1A). The increased PAR levels were not attributable to differences in the expression of PARP1 (Fig. 1B), consistent with the lack of correlation between PARP1 expression and activity previously reported in cell lines (29). Additionally, the latency type of each cell line was confirmed by EBNA1 and LMP1 expression (Fig. 1B). The Kem I (type I) and Kem III (type III) cell lines are fully isogenic with respect to both the host and EBV genomes; thus, the distinct PAR levels in different EBV latency types were not due to inherent genetic differences in the host cells or EBV strains. Likewise, LCL (type III) cells have higher levels of cellular PAR than the Mutu I (type I) cells despite being isogenic with respect to the EBV genome. Therefore, not only does latent EBV infection promote PARylation but the level of PAR induction is also directly related to viral latency type, with EBV-infected cell lines in type III latency possessing the highest levels of PAR.

FIG 1.

Latent EBV infection correlates with increased PAR levels. (A) PAR levels in EBV-negative B cells and type I and type III latently infected EBV-positive B cells. Stars indicate corresponding isogenic cell lines. Results show averages ± standard deviations (SD) and are representative of those from three experiments. (B) Western blot of EBV-positive cells shown in panel A probed for the EBV proteins EBNA1, EBNA2, and LMP1 or the host protein PARP1. Actin served as a loading control. Western blots are representative of those from three independent experiments.

LMP1 activates PARylation.

The differences in PAR levels in fully isogenic Kem I and Kem III cell lines suggest that an EBV protein expressed exclusively during type III latency contributes to the increased PAR levels. Among the proteins expressed during type III latency, LMP1 plays a critical role in cellular transformation (3). LMP1 is an integral membrane protein that promotes B cell differentiation and proliferation by mimicking CD40, resulting in the activation of many cellular signaling pathways, and regulates the expression of epigenetic modifiers (30–32). Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that LMP1 alone is sufficient to increase PAR levels by ectopic expression in the EBV-negative B cell line DG75 and the fibroblast cell line Rat1, in which LMP1 induces cellular transformation (33). Ectopic expression of LMP1 in both DG75 and Rat1 cells elicited increased PAR levels, consistent with LMP1 activating PARylation (Fig. 2A and B) without affecting cell viability (see Fig. S1 in supplemental material). In contrast, ectopic expression of EBNA1, which is present during both type I and type III latency, did not affect PAR levels in Rat1 cells (Fig. 2C). To establish that expression of LMP1 alone is sufficient to elicit increases in PAR levels during latent EBV infection, we knocked down LMP1 levels in the EBV-positive B cell lines LCL, GM13605, and Raji using lentiviral shRNA constructs (Fig. 2D). Knockdown of LMP1 by ∼50% resulted in at least 60% reduction of PAR levels in all three cell lines (Fig. 2E). Additionally, LMP1 knockdown had no effect on cell viability or induction of lytic replication (data not shown). Taken together, these data show that the EBV protein LMP1 alone is sufficient to promote the increased PAR levels found in type III latency.

FIG 2.

LMP1 expression increases PAR levels. DG75 (A) and Rat1 (B) cells were transfected with an LMP1 expression construct or plasmid vector, and PAR levels were measured by ELISA. Results are averages ± SD and are representative of three experiments. LMP1 expression was confirmed by Western blotting, and actin served as a loading control. (C) Rat1 cells were transfected with EBNA1 or an empty vector, and PAR levels were measured by ELISA. Results show averages ± SD and are representative of three experiments. Western blot for EBNA1 confirms expression. Actin served as a loading control. (D) LCL, GM13605, and Raji cells were transduced with shLMP1 or a scrambled lentiviral construct (shCtr) for 96 h, and protein extracts were analyzed by Western blotting for LMP1 and actin (loading control). IB, immunoblot. (E) PAR levels were measured by ELISA in cells treated as described for panel D. Results are averages ± SD and are representative of three experiments.

LMP1 activates PARylation through PARP1.

There are five members of the PARP family that are capable of PARylating (34); of these, PARP1 is the most abundant and well-characterized. Additionally, LMP1 activates the mitogen-activated protein kinase-extracellular signal-related kinase (MAPK-ERK) pathway, which is known to contribute to PARP1 activation (35). Therefore, we specifically tested the hypothesis that LMP1 activates PARP1 to promote PARylation by expressing LMP1 in PARP1-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF PARP1−/−) (Fig. 3A). We used MEFs since LMP1 induces the proliferation of MEFs, demonstrating that these cells are responsive to LMP1 expression (36). Ectopic expression of LMP1 in MEF PARP1−/− cells did not alter PAR levels relative to the control (Fig. 3B), while expression of LMP1 in WT MEFs resulted in a 25% increase in PAR levels (Fig. 3C). To establish that the induction of cellular PAR levels by LMP1 was strictly dependent upon PARP1, MEF PARP1−/− cells stably transduced with an HA-LMP1 expression construct or the pBABE vector were subsequently reconstituted with WT PARP1 or catalytically inactive PARP1 (PARP1 E998A) by transient transfection (Fig. 3D). As expected, restoring PARP1 expression in MEF PARP1−/− resulted in increased PAR levels. Expressing both LMP1 and WT PARP1 induced significantly higher PAR levels compared to expression of PARP1 alone (Fig. 3E), and expression of catalytically inactive PARP1 failed to increase PAR levels (Fig. 3E). Thus, the increase in cellular PARylation induced by LMP1 is strictly dependent upon the catalytic activity of PARP1 (Fig. 3E). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that the EBV oncoprotein LMP1 promotes PARylation through a PARP1-dependent mechanism.

FIG 3.

LMP1 increases PAR through PARP1. (A) Western blot for PARP1 in WT MEF and MEF PARP1−/− cells confirms PARP1 deficiency. Actin served as a loading control. MEF PARP1−/− (B) and WT MEF (C) were transfected with an empty plasmid vector or LMP1 expression construct, and PAR levels were measured by ELISA. Results show averages ± SD and are representative of three experiments. Western blot for LMP1 confirms expression. Actin served as a loading control. (D) MEF PARP1−/− cells stably expressing pBabe (empty vector) or HA-LMP1 via retroviral transduction were transfected with an empty vector, WT PARP1, or a catalytically inactive PARP1 construct (PARP1 E998A). LMP1 and PARP1 expression were confirmed by Western blotting, and actin served as a loading control. The asterisk indicates the PARP1 band. (E) PAR levels in MEF PARP1−/− cells shown in panel D were measured by ELISA and are graphed as percent PARP1 activity, with PARP1 activity in MEF PARP1−/− cells stably expressing pBabe and transfected with the empty vector set at 100%. Results are averages ± SD and are representative of those from three experiments. Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks (*, P < 0.1).

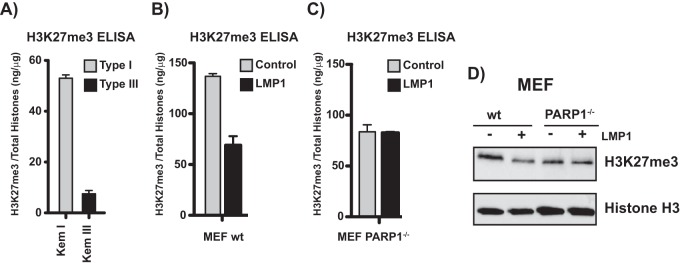

LMP1 decreases H3K27me3 through PARP1.

The activation of PARP1 by LMP1 may have important consequences for the expression of host genes and associated cell functions. PARP1 regulates global gene expression by altering chromatin (37, 38), and we recently reported a reciprocal relationship between PARP1 activity and the expression and function of EZH2 (18). EZH2 is the catalytic subunit of the polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) that mediates trimethylation of lysine 27 of histone H3 (H3K27me3), a repressive histone mark that is associated with gene silencing (39). PARP1 activity suppresses the expression of EZH2, which blocks accumulation of H3K27me3 at EZH2 target genes and prevents gene silencing (18). Thus, the activation of PARP1 by LMP1 should decrease global H3K27me3 levels in type III compared to type I cells. The levels of H3K27me3 were measured by ELISA in histones isolated from the isogenic Kem I (type I) and Kem III (type III) cell lines. Kem III cells had approximately 5-fold lower global H3K27me3 levels than Kem I cells (Fig. 4A). This is consistent with expression of LMP1 and higher levels of PAR in Kem III cells (Fig. 1A). We next measured H3K27me3 levels by ELISA in MEFs transfected with LMP1. LMP1 expression yielded a more than 50% decrease in global H3K27me3 levels (Fig. 4B). To determine if LMP1 regulates H3K27me3 through PARP1, we expressed LMP1 in MEF PARP1−/− cells and measured H3K27me3 levels. LMP1 expression did not change H3K27me3 levels in the absence of PARP1 (Fig. 4C). Similar results were obtained in Western blots of histone extracts isolated from MEF and MEF PARP1−/− in the absence or presence of LMP1 (Fig. 4D). Taken together, these results suggest that LMP1 expression decreases H3K27me3 levels through a PARP1-dependent mechanism.

FIG 4.

LMP1 decreases global H3K27me3 levels through PARP1. (A) H3K27me3 levels measured by ELISA from histone extracts from the isogenic Kem I and Kem III cell lines. Bars represent the mean level (±SD) of H3K27me3 normalized to total histones. Results are representative of three experiments. WT MEF (B) and MEF PARP1−/− (C) cells were transfected with a plasmid vector or an LMP1 expression construct, and H3K27me3 levels in isolated histone extracts were measured by ELISA. Bars represent the mean level of H3K27me3 normalized to total histones ± SD. Results are representative of three experiments. (D) Western blot of histone extracts from WT MEF or MEF PARP1−/− transfected with an empty vector or LMP1 and probed for H3K27me3. Histone H3 serves as a loading control. The image is representative of three experiments.

LMP1 regulates a subset of its target gene expression through PARP1.

Since LMP1 reduced global cellular H3K27me3 levels, we explored whether LMP1 induced host gene expression through the PARP1/EZH2 axis by examining the PARP1 dependence of c-Fos and EGR1 expression, two LMP1 target genes that play a critical role in LMP1-induced tumorigenesis (40, 41). Using the well-established PARP inhibitor olaparib, PARP activity was inhibited in the type III latently infected lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs), and H3K27me3 deposition was measured near the transcription start site (TSS) of c-Fos and EGR1 by ChIP. PARP inhibition promoted the accumulation of H3K27me3 near the transcription start site of both c-Fos and EGR1, consistent with the positive effect of LMP1 on gene expression through PARP1 (Fig. 5A). Treatment of LCLs with olaparib also significantly decreased the expression of c-Fos and EGR1, measured by RT-quantitative PCR (qPCR) (Fig. 5B), suggesting that the accumulation of H3K27me3 upon PARP inhibition was sufficient to abrogate the expression of c-Fos and EGR1. Additionally, PARP inhibition in two other type III latently infected B cell lines was sufficient to decrease the expression of c-Fos and EGR1 (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). To determine that the inhibitory effect of olaparib on the transcription of LMP1 targets was specifically through PARP1, we depleted PARP1 in LCLs and assessed c-Fos and EGR1 transcript levels by RT-qPCR (see Fig. S3). We observed that PARP1 depletion phenocopied the effects of olaparib. Thus, PARP1 activity is important for LMP1-induced activation of two target genes associated with tumorigenesis.

FIG 5.

PARP inhibition offsets LMP1-induced activation of its target genes, c-Fos and EGR1. (A) Quantitative chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay for H3K27me3 occupancy at the c-Fos (left) or EGR1 (right) transcription start site (TSS) in control cells or LCLs treated with 2.5 μM olaparib for 72 h. Results are expressed as the percentage of input chromatin material ± SD and are representative of two independent experiments. (B) c-Fos (left) and EGR1 (right) mRNA transcripts were measured by RT-qPCR in LCLs left untreated or treated with 2.5 μM olaparib for 72 h. c-Fos and EGR1 mRNA levels in untreated cells were normalized to 1, and results are expressed relative to the untreated cells. Bars represent the mean level of expression ± SD and are representative of three independent experiments.

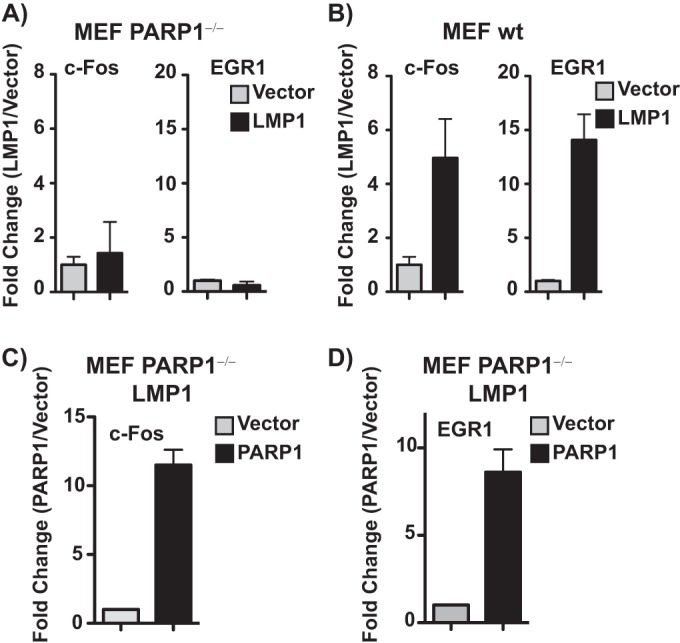

The specific requirement for PARP1 in LMP1-mediated activation of c-Fos and EGR1 gene expression was further directly tested using PARP1−/− MEFs ectopically expressing LMP1. LMP1 failed to induce the expression of c-Fos and EGR1 in PARP1−/− MEFs (Fig. 6A) but induced robust transcription of both c-Fos and EGR1 in WT MEFs (Fig. 6B). Restoration of PARP1 expression in PARP1−/− MEFs stably expressing LMP1 restored c-Fos and EGR1 expression (Fig. 6C and D). The requirement for PARP1 to induce c-Fos and EGR1 expression in both type III latently infected EBV cells and MEFs supports an important role for the PARP1/EZH2 axis in activation of host gene expression by LMP1 and suggests a crucial role for this pathway in EBV-associated oncogenesis.

FIG 6.

LMP1 regulates the expression of c-Fos and EGR1 through PARP1. MEF PARP1−/− (A) and WT MEF (B) cells were transfected with an empty plasmid vector or an LMP1 expression construct. Bars represent the mean level of c-Fos or EGR1 mRNA expression normalized to the empty vector ± standard errors of the means (SEM) as measured by RT-qPCR. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and results are representative of three independent experiments. (C and D) MEF PARP1−/− cells stably expressing HA-LMP1 were transfected with an empty plasmid vector or a WT PARP1 expression construct. Bars represent the mean level of c-Fos or EGR1 mRNA expression normalized to the empty vector ± SD as measured by RT-qPCR. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and results are representative of three independent experiments.

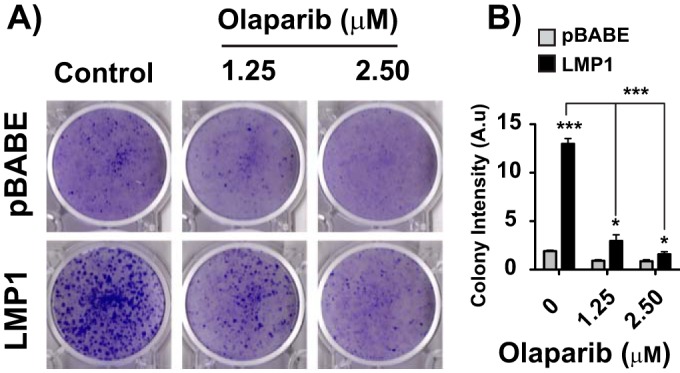

PARP1 activity contributes to LMP1-induced cellular transformation.

Since LMP1 promotes the expression of host genes associated with tumorigenesis and cell growth (42) through the epigenetic effects of PARP1, we assessed whether LMP1-mediated changes in gene expression through PARP1 contribute to cellular transformation. The induction of focus formation in the Rat1 cell line is a well-established assay to measure LMP1-mediated transformation (43). If PARP1 contributes to LMP1-induced transformation, then the PARP inhibitor olaparib should reduce or eliminate focus formation. To test this, Rat1 cells were retrovirally transduced with an empty vector (pBABE) or HA-LMP1, and focus formation was measured in the presence or absence of olaparib (Fig. 7). LMP1 expression increased Rat1 focus formation relative to pBABE (Fig. 7A), consistent with previous observations (43). Additionally, PARP inhibition with 1.25 or 2.5 μM olaparib reduced LMP1-mediated focus formation (Fig. 7A). Focus formation was quantified by the ColonyArea plugin function of the ImageJ software analysis program to determine the fractional cellular surface area per plate as a percentage of area occupied by all cell colonies detected using crystal violet staining and efficiency of focus formation as measured by the staining intensity of individual colonies (44). The induction of Rat1 cell focus formation by LMP1 was readily inhibited by olaparib (Fig. 7B). Rat1 cell focus formation was more significantly (P ≤ 0.001 by ANOVA) impaired in LMP1-transduced cells compared to the vector-transduced control cells (Fig. 7B). Taken together, these findings imply that PARP1 activity contributes to LMP1-induced cellular transformation and can be repressed by inhibition of PARP1. Olaparib is a pan-PARP inhibitor that affects multiple PARP family members. As such, both PARP1 and PARP2 are sensitive to olaparib at the concentrations used in the Rat1 cellular transformation assay. To establish the relative contributions of PARP1 to LMP1-mediated cellular transformation, we used lentiviral shRNA constructs to abrogate PARP1 expression in LMP1-transduced Rat1 cells (Fig. 8A). The shRNA construct reduced PARP1 levels without affecting the expression of PARP2 or LMP1 (Fig. 8A). PARP1 knockdown significantly decreased focus formation and colony density, as measured by ImageJ in cells expressing LMP1 (Fig. 8B to D). Rat1 cells expressing LMP1 also had an elongated or spindle-shaped cellular morphology that was clearly distinct from the vector-transduced controls and was reverted upon knockdown of PARP1 (see Fig. S4 in supplemental material). Assessment of colony size by fluorescence microscopy using ectopic GFP reporter expression, introduced as part of the lentiviral shRNA construct, also revealed that knockdown of PARP1 decreased colony density relative to the nontargeted control (Fig. 8E), confirming that PARP1 plays an important role in LMP1-mediated cellular transformation. Thus, these results establish the importance of PARP1 activity in LMP1-mediated cellular transformation.

FIG 7.

PARP inhibition reduces LMP1-mediated cellular transformation. (A) Rat1 cells were retrovirally transduced with the pBABE vector or HA-LMP1. Stably transduced pBABE- or HA-LMP1-expressing cells were treated with 1.25 μM olaparib, 2.5 μM olaparib, or DMSO for 3 days. Medium was then replaced with fresh medium and focus formation was analyzed after 14 days. The image is representative of six independent experiments. (B) Colony intensity for each condition in panel A was determined by the ImageJ plugin ColonyArea (n = 6; means ± SEM). A.u, arbitrary units. Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks (***, P ≤ 0.001).

FIG 8.

PARP1 knockdown reduces LMP1-mediated cellular transformation. (A) Rat1 cells stably expressing HA-LMP1 were transduced with shPARP1 or a scrambled lentiviral construct (shCtr) for 72 h, and protein extracts were analyzed by Western blotting for PARP1, PARP2, LMP1, and actin (loading control). The Western blots are representative of those from three independent experiments. (B) Focus formation analysis of Rat1 cells stably expressing LMP1 following PARP1 depletion by an shPARP1 lentiviral construct. Puromycin was added 24 h after PARP1 depletion for selection. Cells were stained 7 days postlentiviral transduction. The image is representative of three independent experiments. (C) Number of colonies for each condition shown in panel B determined by counting. Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks (**, P < 0.05). (D) Quantification of colony intensity using ImageJ software analysis. Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks (*, P < 0.1). (E) Photomicrographs of phase contrast and GFP fluorescence of Rat1 cells stably expressing LMP1 transduced with shControl or shPARP1 GFP lentiviral particles. Images were acquired with an Envos FL cell imaging system using a 20× objective; the white bar represents 400 μm.

Overall, these results show that EBV latency elicits PARylation and further identifies a novel mechanism by which the EBV oncoprotein LMP1 regulates host gene expression through the activity of PARP1. By activating PARP1, LMP1 hampers the function of the chromatin-modifying enzyme EZH2, which subsequently suppresses the accumulation of the repressive histone mark H3K27me3. This leads to aberrant transcription of host genes that play an important role in LMP1-mediated tumorigenesis.

DISCUSSION

This study establishes a novel, functional link between EBV latent infection and the posttranslational modification termed PARylation. The type III latent gene expression program is specifically associated with a significant increase in cellular PARylation compared to type I and is dependent upon the expression of the EBV oncoprotein LMP1. LMP1 hijacks the host epigenetic machinery to alter the expression of host genes by activating the chromatin-modifying enzyme PARP1. The induction of PARylation mediated by LMP1 is also crucial for EBV-driven oncogenesis. PARP inhibition and PARP1 depletion attenuated the capacity of LMP1 to transform rodent fibroblasts, indicating that targeting PARP1 activity can antagonize LMP1-driven cellular transformation. Thus, the epigenetic alterations induced by LMP1 via PARP1 activation and PARylation contribute to oncogenic transformation associated with EBV infection.

Expression of LMP1 alone is sufficient to activate PARP1 and promote a series of PARP1-dependent alterations in chromatin structure. We have previously shown that PARP1 activity regulates the expression and function of EZH2, preventing gene silencing mediated by the repressive histone mark H3K27me3 (18). In this study, we report for the first time the induction of two tumor-promoting genes, c-Fos and EGR1 (45, 46), as key targets of LMP1 through the PARP1/EZH2 axis. Since LMP1-expressing cells have lower global levels of H3K27me3, the disruption of host gene regulation likely extends beyond c-Fos and EGR1. These data suggest that the PARP1/EZH2 axis is a major regulatory pathway utilized by LMP1, which promotes the expression of cellular genes involved in proliferation and transformation, contributing to LMP1-induced oncogenesis. The investigation of host gene expression driven by LMP1 through PARP1/EZH2 on a genome-wide scale is ongoing.

This work establishes that LMP1 utilizes PARP1 to target EZH2 and reduce H3K27me3; however, LMP1 also promotes H3K27me3 demethylation through activation of KDM6B (47). Thus, EBV uses at least two nonredundant mechanisms to regulate this repressive histone mark, highlighting the importance of H3K27me3 as a key regulator of LMP1-induced alterations in host gene expression and, in general, supporting an important role for EBV effects on the host epigenome. Our observations are consistent with previous work showing that LMP1 expression decreases global H3K27me3 levels (48) and is further supported by the fact that LMP1 induces expression of the oncoprotein ΔNp73α by preventing EZH2 binding and H3K27me3 at the promoter (49). Our work extends these previous findings by providing a mechanism demonstrating that LMP1, through PARP1, affects EZH2 and H3K27me3. Since EZH2 also promotes gene expression by mechanisms that are independent of its catalytic activity (50, 51), EBV may exploit multiple regulatory functions of EZH2, some of which directly alter host transcription without associated epigenetic modifications. Therefore, this work defines a mechanism for LMP1-mediated host gene expression regulation via PARP1-dependent inhibition of H3K27me3 production and possibly suppression of EZH2 transactivation.

PARP1 regulates chromatin structure through the PARylation of histones and chromatin-modifying enzymes (16, 52). For example, PARP1 maintains the active histone mark H3K4me3 by PARylating the histone demethylase KDM5B, repressing its activity (16). Thus, by activating PARP1, LMP1 and EBV may affect a broad network of PARP1-regulated epigenetic modifications, not just EZH2, that act in concert to alter gene expression.

Because PARP1 plays important roles in many cellular processes, other viruses may have also evolved mechanisms that target PARP1 activity to support viral infection. Herpesviruses encode proteins capable of transforming cells similar to LMP1, including the K1 protein of KSHV (53), suggesting that viral targeting of PARP1 is a common mechanism of induction of cellular transformation. If so, PARP inhibition may be a widely applicable strategy to minimize the impact of virus-mediated disruptions in host gene regulation. Considering that EBV and KSHV contribute to cancer incidence on a global scale (2), PARP inhibition may be an effective treatment against some of the most prevalent virus-associated malignancies.

Our recent work indicates that PARP1 regulates B cell receptor stimulation and the immune response (18). This link between PARP activity and B cell function is supported by the observation that transcription factors that participate in the immune response, such as interleukin-2 (IL-2) and gamma interferon (IFN-γ), likely contribute to PARP-mediated gene regulation (18, 54). In addition, PARP1 is an important activator of NF-κB (55). Therefore, PARP1 may be an important target for EBV as a major regulator of gene expression through chromatin modifications and as an essential factor for proper B cell function to promote cell and, therefore, virus survival.

The distinct levels of cellular PARylation observed in type I and type III cell lines strongly suggest that the LMP1/PARP1/EZH2 axis regulates EBV latency. Since the latent EBV genome does not usually integrate into the host genome but is maintained as a chromatin-associated episome (56, 57), alterations in the epigenome likely represent the primary means for the virus to regulate gene expression during latency. LMP1 may maintain the expression of type III-associated genes by reducing H3K27me3 levels to prevent epigenetic silencing of latent EBV genes, sustaining viral transcription and ensuring persistence.

While the mechanisms utilized by LMP1 to activate PARP1 have yet to be elucidated, one potential model that is supported by the literature is via the MAPK-ERK pathway. LMP1 activates MAPK-ERK (35), and PARP1 is activated by interaction with phosphorylated ERK2 (58). Future studies are needed to ascertain the relative contribution of this signaling pathway and others to LMP1-mediated activation of PARP1.

This work clearly establishes that LMP1 activates PARP1 and further defines that EBNA1, expressed in all EBV latency types, does not increase PAR levels. However, further studies are necessary to establish whether other EBV proteins, such as EBNA2 or EBNA3s, contribute to PARP1 activation in type III latently infected cells.

Epigenetic factors are targetable by drugs. Therefore, by identifying the epigenetic regulator PARP1 as an important target of LMP1-mediated alteration in host gene expression and LMP1-induced cellular transformation, this dissertation suggests a new strategy for the treatment of EBV-associated malignancies. The PARP inhibitor olaparib is already approved for use by the FDA; the concentrations used are approximately half the level attained in peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from ovarian cancer patients enrolled in clinical trials, making it clinically relevant (59). The profile of side effects from these ongoing clinical trials suggests that inhibiting PARP in B cells is safe and effective. Because current efforts designed to target individual LMP1-activated signaling pathways are insufficient to completely abrogate LMP1-driven oncogenesis, combining olaparib with these inhibitors may be an effective strategy to potentiate targeting of EBV-associated malignancies.

Taken together, we define a new regulatory mechanism by which EBV uses LMP1 to hijack the host epigenetic machinery through the induction of PARylation. LMP1 alters the expression of host genes through the PARP1/EZH2 axis, which contributes to LMP1-induced cell transformation. Since LMP1 drives cellular transformation, playing an important role in EBV-associated oncogenesis, using PARP1 inhibitors to target this pathway may be an effective strategy to reduce the carcinogenic risk associated with EBV infection.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Rona Scott and Nancy Raab-Traub for LMP1 expression constructs, Zhao-Qi Wang for WT MEF and MEF PARP1−/− cells, John Pascal for the PARP1 expression constructs, and Michael Denny for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R00AI099153 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to I.T.

The study design, data collection and interpretation, and the decision to publish this work were not influenced by funding sources.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01180-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Luzuriaga K, Sullivan JL. 2010. Infectious mononucleosis. N Engl J Med 362:1993–2000. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1001116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkin DM. 2006. The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002. Int J Cancer 118:3030–3044. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young LS, Rickinson AB. 2004. Epstein-Barr virus: 40 years on. Nat Rev Cancer 4:757–768. doi: 10.1038/nrc1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang M-S, Kieff E. 2015. Epstein-Barr virus latent genes. Exp Mol Med 47:e131. doi: 10.1038/emm.2014.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arvin A, Campadelli-Fiume G, Mocarski E, Moore PS, Roizman B, Whitley R, Yamanishi K, Young LS, Arrand JR, Murray PG. 2007. EBV gene expression and regulation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babcock GJ, Hochberg D, Thorley-Lawson AD. 2000. The expression pattern of Epstein-Barr virus latent genes in vivo is dependent upon the differentiation stage of the infected B cell. Immunity 13:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)00049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levitskaya J, Sharipo A, Leonchiks A, Ciechanover A, Masucci MG. 1997. Inhibition of ubiquitin/proteasome-dependent protein degradation by the Gly-Ala repeat domain of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94:12616–12621. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammerschmidt W. 2015. The epigenetic life cycle of Epstein-Barr virus. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 390:103–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lieberman PM. 2015. Chromatin structure of Epstein-Barr virus latent episomes. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 390:71–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D'Amours D, Desnoyers S, D'Silva I, Poirier GG. 1999. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation reactions in the regulation of nuclear functions. Biochem J 342(Part 2):249–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huletsky A, de Murcia G, Muller S, Hengartner M, Ménard L, Lamarre D, Poirier GG. 1989. The effect of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation on native and H1-depleted chromatin. A role of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation on core nucleosome structure. J Biol Chem 264:8878–8886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kraus WL, Lis JT. 2003. PARP goes transcription. Cell 113:677–683. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00433-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathis G, Althaus FR. 1987. Release of core DNA from nucleosomal core particles following (ADP-ribose)n-modification in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 143:1049–1054. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(87)90358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poirier GG, de Murcia G, Jongstra-Bilen J, Niedergang C, Mandel P. 1982. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of polynucleosomes causes relaxation of chromatin structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 79:3423–3427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.11.3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tulin A, Spradling A. 2003. Chromatin loosening by poly(ADP)-ribose polymerase (PARP) at Drosophila puff loci. Science 299:560–562. doi: 10.1126/science.1078764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishnakumar R, Kraus WL. 2010. PARP-1 regulates chromatin structure and transcription through a KDM5B-dependent pathway. Mol Cell 39:736–749. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zampieri M, Passananti C, Calabrese R, Perilli M, Corbi N, De Cave F, Guastafierro T, Bacalini MG, Reale A, Amicosante G, Calabrese L, Zlatanova J, Caiafa P. 2009. Parp1 localizes within the Dnmt1 promoter and protects its unmethylated state by its enzymatic activity. PLoS One 4:e4717–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin KA, Cesaroni M, Denny MF, Lupey LN, Tempera I. 2015. Global transcriptome analysis reveals that poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerase 1 regulates gene expression through EZH2. Mol Cell Biol 35:3934–3944. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00635-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mattiussi S, Tempera I, Matusali G, Mearini G, Lenti L, Fratarcangeli S, Mosca L, D'Erme M, Mattia E. 2007. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase impairs Epstein Barr virus lytic cycle progression. Infect Agents Cancer 2:18. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tempera I, Deng Z, Atanasiu C, Chen C-J, D'Erme M, Lieberman PM. 2010. Regulation of Epstein-Barr virus OriP replication by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1. J Virol 84:4988–4997. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02333-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang ZQ, Stingl L, Morrison C, Jantsch M, Los M, Schulze-Osthoff K, Wagner EF. 1997. PARP is important for genomic stability but dispensable in apoptosis. Genes Dev 11:2347–2358. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.18.2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langelier M-F, Planck JL, Roy S, Pascal JM. 2011. Crystal structures of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) zinc fingers bound to DNA: structural and functional insights into DNA-dependent PARP-1 activity. J Biol Chem 286:10690–10701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.202507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steffen JD, Tholey RM, Langelier M-F, Planck JL, Schiewer MJ, Lal S, Bildzukewicz NA, Yeo CJ, Knudsen KE, Brody JR, Pascal JM. 2014. Targeting PARP-1 allosteric regulation offers therapeutic potential against cancer. Cancer Res 74:31–37. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moffat J, Grueneberg DA, Yang X, Kim SY, Kloepfer AM, Hinkle G, Piqani B, Eisenhaure TM, Luo B, Grenier JK, Carpenter AE, Foo SY, Stewart SA, Stockwell BR, Hacohen N, Hahn WC, Lander ES, Sabatini DM, Root DE. 2006. A lentiviral RNAi library for human and mouse genes applied to an arrayed viral high-content screen. Cell 124:1283–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. 2005. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science 307:1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Everly DN, Mainou BA, Raab-Traub N. 2004. Induction of Id1 and Id3 by latent membrane protein 1 of Epstein-Barr virus and regulation of p27/Kip and cyclin-dependent kinase 2 in rodent fibroblast transformation. J Virol 78:13470–13478. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.24.13470-13478.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tempera I, Wiedmer A, Dheekollu J, Lieberman PM. 2010. CTCF prevents the epigenetic drift of EBV latency promoter Qp. PLoS Pathog 6:e1001048. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tempera I, Klichinsky M, Lieberman PM. 2011. EBV latency types adopt alternative chromatin conformations. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002180. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zaremba T, Ketzer P, Cole M, Coulthard S, Plummer ER, Curtin NJ. 2009. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 polymorphisms, expression and activity in selected human tumour cell lines. Br J Cancer 101:256–262. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dawson CW, Port RJ, Young LS. 2012. The role of the EBV-encoded latent membrane proteins LMP1 and LMP2 in the pathogenesis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC). Semin Cancer Biol 22:144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graham JP, Arcipowski KM, Bishop GA. 2010. Differential B-lymphocyte regulation by CD40 and its viral mimic, latent membrane protein 1. Immunol Rev 237:226–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soni V, Cahir-McFarland E, Kieff E. 2007. LMP1 TRAFficking activates growth and survival pathways, p 173–187. In Wu H. (ed), TNF receptor associated factors (TRAFs). Springer New York, New York, NY. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang D, Liebowitz D, Kieff E. 1985. An EBV membrane protein expressed in immortalized lymphocytes transforms established rodent cells. Cell 43:831–840. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daugherty MD, Young JM, Kerns JA, Malik HS. 2014. Rapid evolution of PARP genes suggests a broad role for ADP-ribosylation in host-virus conflicts. PLoS Genet 10:e1004403. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu L-T, Peng J-P, Chang H-C, Hung W-C. 2003. RECK is a target of Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1. Oncogene 22:8263–8270. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang X, Sham JS, Ng MH, Tsao SW, Zhang D, Lowe SW, Cao L. 2000. LMP1 of Epstein-Barr virus induces proliferation of primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts and cooperatively transforms the cells with a p16-insensitive CDK4 oncogene. J Virol 74:883–891. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.2.883-891.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krishnakumar R, Gamble MJ, Frizzell KM, Berrocal JG, Kininis M, Kraus WL, Lee W. 2008. Reciprocal binding of PARP-1 and histone H1 at promoters specifies transcriptional outcomes. Science 319:819–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1149250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frizzell KM, Gamble MJ, Berrocal JG, Zhang T, Krishnakumar R, Cen Y, Sauve AA, Kraus WL. 2009. Global analysis of transcriptional regulation by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 and poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem 284:33926–33938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.023879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cao R, Wang L, Wang H, Xia L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Jones RS, Zhang Y. 2002. Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in Polycomb-group silencing. Science 298:1039–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1076997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vaysberg M, Hatton O, Lambert SL, Snow AL, Wong B, Krams SM, Martinez OM. 2008. Tumor-derived variants of Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 induce sustained Erk activation and c-Fos. J Biol Chem 283:36573–36585. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802968200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim JH, Kim WS, Kang JH, Lim H-Y, Ko Y-H, Park C. 2007. Egr-1, a new downstream molecule of Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1. FEBS Lett 581:623–628. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kieser A, Sterz KR. 2015. The latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1). Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 391:119–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moorthy RK, Thorley-Lawson DA. 1993. All three domains of the Epstein-Barr virus-encoded latent membrane protein LMP-1 are required for transformation of rat-1 fibroblasts. J Virol 67:1638–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guzmán C, Bagga M, Kaur A, Westermarck J, Abankwa D. 2014. ColonyArea: an ImageJ plugin to automatically quantify colony formation in clonogenic assays. PLoS One 9:e92444. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Angel P, Karin M. 1991. The role of Jun, Fos and the AP-1 complex in cell-proliferation and transformation. Biochim Biophys Acta 1072:129–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adamson ED, Mercola D. 2002. Egr1 transcription factor: multiple roles in prostate tumor cell growth and survival. Tumour Biol 23:93–102. doi: 10.1159/000059711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anderton JA, Bose S, Vockerodt M, Vrzalikova K, Wei W, Kuo M, Helin K, Christensen J, Rowe M, Murray PG, Woodman CB. 2011. The H3K27me3 demethylase, KDM6B, is induced by Epstein-Barr virus and over-expressed in Hodgkin's Lymphoma. Oncogene 30:2037–2043. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hernando H, Islam AB, Rodríguez-Ubreva J, Forné I, Ciudad L, Imhof A, Shannon-Lowe C, Ballestar E. 2014. Epstein-Barr virus-mediated transformation of B cells induces global chromatin changes independent to the acquisition of proliferation. Nucleic Acids Res 42:249–263. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Accardi R, Fathallah I, Gruffat H, Mariggiò G, Le Calvez-Kelm F, Voegele C, Bartosch B, Hernandez-Vargas H, McKay J, Sylla BS, Manet E, Tommasino M. 2013. Epstein-Barr virus transforming protein LMP-1 alters B cells gene expression by promoting accumulation of the oncoprotein ΔNp73α. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003186. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shi B, Liang J, Yang X, Wang Y, Zhao Y, Wu H, Sun L, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Li R, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Hong M, Shang Y. 2007. Integration of estrogen and Wnt signaling circuits by the polycomb group protein EZH2 in breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol 27:5105–5119. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00162-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nuytten M, Beke L, Van Eynde A, Ceulemans H, Beullens M, Van Hummelen P, Fuks F, Bollen M. 2008. The transcriptional repressor NIPP1 is an essential player in EZH2-mediated gene silencing. Oncogene 27:1449–1460. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim MY, Zhang T, Kraus WL. 2005. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation by PARP-1: “PAR-laying” NADM. Genes Dev 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee H, Veazey R, Williams K, Li M, Guo J, Neipel F, Fleckenstein B, Lackner A, Desrosiers RC, Jung JU. 1998. Deregulation of cell growth by the K1 gene of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Nat Med 4:435–440. doi: 10.1038/nm0498-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ghonim MA, Pyakurel K, Ibba SV, Al-Khami AA, Wang J, Rodriguez P, Rady HF, El-Bahrawy AH, Lammi MR, Mansy MS, Al-Ghareeb K, Ramsay A, Ochoa A, Naura AS, Boulares AH. 2015. PARP inhibition by olaparib or gene knockout blocks asthma-like manifestation in mice by modulating CD4(+) T cell function. J Transl Med 13:225. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0583-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hassa PO, Hottiger MO. 1999. A role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in NF-kappaB transcriptional activation. Biol Chem 380:953–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nonoyama M, Pagano JS. 1972. Separation of Epstein-Barr virus DNA from large chromosomal DNA in non-virus-producing cells. Nat New Biol 238:169–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lindahl T, Adams A, Bjursell G, Bornkamm GW, Kaschka-Dierich C, Jehn U. 1976. Covalently closed circular duplex DNA of Epstein-Barr virus in a human lymphoid cell line. J Mol Biol 102:511–530. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90331-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cohen-Armon M, Visochek L, Rozensal D, Kalal A, Geistrikh I, Klein R, Bendetz-Nezer S, Yao Z, Seger R. 2007. DNA-independent PARP-1 activation by phosphorylated ERK2 increases Elk1 activity: a link to histone acetylation. Mol Cell 25:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bundred N, Gardovskis J, Jaskiewicz J, Eglitis J, Paramonov V, McCormack P, Swaisland H, Cavallin M, Parry T, Carmichael J, Dixon JM. 2013. Evaluation of the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of the PARP inhibitor olaparib: a phase I multicentre trial in patients scheduled for elective breast cancer surgery. Investig New Drugs 31:949–958. doi: 10.1007/s10637-012-9922-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.