Abstract

Background

Hospitalizations in patients with metastatic cancer occur commonly at the end of life but have not been well-described in individuals with metastatic breast cancer.

Aim

To describe the reasons for admission and frequency of palliative care and hospice utilization in hospitalized patients with metastatic breast cancer.

Design

This was a retrospective chart review of patients who had their first hospitalization with a diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer between 1/1/2009 and 12/31/2010. To standardize follow-up time, we collected data for three years post the index hospitalization.

Setting/participants

We identified 123 consecutive patients who were hospitalized for the first time with a diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer at a single, tertiary care center.

Results

Uncontrolled symptoms accounted for half (50%, 62/123) of index admissions. The majority of patients died during the follow-up period (76%, 94/123), and the median time from index admission to death was six months (range, 0 to 34). Approximately half (53%, 50/94) died in the hospital or within 14 days of last hospital discharge, and less than one-third (29%, 27/94) were referred to hospice after their last hospitalization. The inpatient palliative care team evaluated 57% (54/94) of those who died at least once during an admission, but only 17% (16/94) of patients attended an outpatient palliative care appointment.

Conclusions

Hospitalized patients with metastatic breast cancer are commonly admitted for uncontrolled symptoms and have a poor prognosis. However, only a minority receive outpatient palliative care or are referred to hospice during their last hospitalization prior to death.

Keywords: Breast neoplasms, neoplasm metastasis, hospitalization, palliative care, hospices

Introduction

Patients with advanced cancer often receive intensive medical care at the end of life (EOL) (1-3). Data from the Dartmouth Atlas highlight that the majority of advanced cancer patients are hospitalized in the last month of life, and there have been rising rates of intensive care unit (ICU) admissions over the last decade (1). Although the majority of patients with cancer prefer to die at home (4-6), about 25% of patients die during one of these hospital admissions (1). Additionally, almost 40% of patients with advanced cancer do not enroll in hospice in the last month of life (1). Even in those patients who do enroll in hospice, the average patient only spends approximately nine days on hospice (1). These high rates of hospitalization and relatively low rates of hospice utilization are two markers of high-intensity EOL care in patients with an incurable cancer diagnosis.

This intensity of medical care at the EOL impacts the quality of life and the experience of patients and their caregivers. Studies have shown that patients with cancer who die in the hospital or the ICU experience more physical and emotional distress and lower quality of life at the EOL compared to patients who die at home with hospice services (7). Moreover, bereaved caregivers experience high rates of posttraumatic stress disorder and prolonged grief disorder when their loved ones die in the hospital or ICU (7). Conversely, patients with longer admissions to hospice report better quality of life, and their bereaved family members have lower rates of depression (8-10). Therefore, the intensity of medical care at the EOL impacts patients’ quality of life, physical and psychological distress, as well as caregivers’ bereavement and psychological outcomes.

Patients with metastatic breast cancer (MBC) are a key population to examine in terms of the intensity of medical care at the EOL since breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality in women in the United States (11). However, studies examining the intensity of medical care at the EOL for patients with MBC are limited. One prior study suggested that patients with MBC were more likely to receive intensive care compared to those with other advanced solid malignancies (12). Specifically, they were more likely to be treated with chemotherapy within two weeks of death and were less likely to receive hospice services (12). In a retrospective database review of patients who died from breast cancer, one-third of patients with MBC died without a hospice referral (13). These patients were more likely to die in a hospital setting, when compared to patients with MBC who were referred to hospice (13). This data underscores the need for more information about medical care at the EOL in patients with MBC, with a specific focus on identifying a subset of patients who are at a high risk for further morbidity and mortality.

The goal of this study was to describe the frequency and reason for hospitalization and hospice and palliative care utilization in patients hospitalized for the first time with a diagnosis of MBC. Though the median survival of MBC is approximately 18-24 months (14-18) the course of MBC can be difficult to predict with approximately one-quarter of women surviving five or more years (19). We chose to focus on hospitalized patients with MBC as we felt they represent a high-risk cohort of MBC patients with a shorter prognosis. This data will provide essential information about the morbidity, mortality, and utilization of palliative care and hospice services in hospitalized patients with MBC and will identify potential targets for interventions to improve the quality of their EOL care.

Methods

Study population

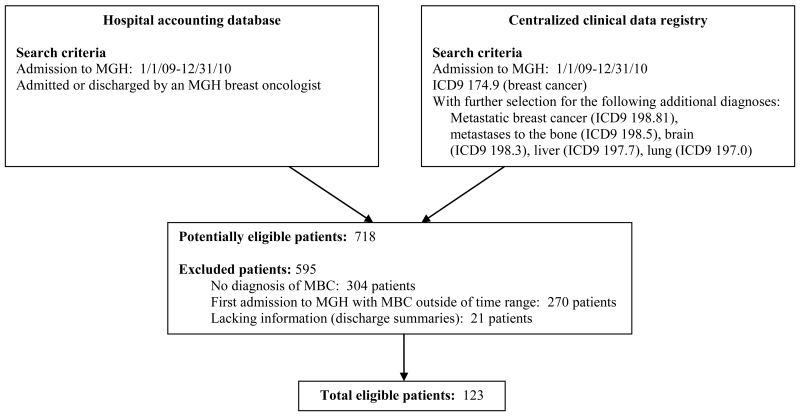

Our study cohort included consecutive patients with MBC who were hospitalized for the first time (index hospitalization) with a diagnosis of metastatic disease. Patients were admitted through the emergency department, from clinic, or electively. To standardize the follow-up time of our study population, we collected data for three years post the index hospitalization. The median survival of MBC is 18-24 months (14-18) and patients who are admitted to the hospital likely represent a more ill cohort of the population; thus a three-year window should provide adequate time to collect data on EOL outcomes. Patients were eligible for inclusion in this retrospective chart review if they had their first oncology hospital admission to Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) with MBC between 1/1/2009 and 12/31/2010. We utilized the hospital billing database and a centralized clinical data registry to accurately identify this cohort. First, we searched the hospital accounting database for patients who had an admission between 1/1/2009 and 12/31/2010 and who were admitted or discharged by an MGH breast oncologist since individual oncologists admitted their own patients during this time period. We then conducted a centralized clinical data registry to create a list of patients who had inpatient encounters at MGH between 1/1/09 and 12/31/10 with a diagnosis of breast cancer (ICD9 174.9). From this list, we selected those patients who also had a diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer (ICD9 198.81) or metastases to the bone (ICD9 198.5), brain (ICD9 198.3), liver (ICD9 197.7), or lung (ICD9 197.0) linked to their medical record. To select patients who received the majority of their cancer care at MGH, we limited our study population to patients with an MGH outpatient medical oncologist, with a minimum of three visits in the ambulatory care setting during the study period. From this list, we manually reviewed each record to confirm that patients met the inclusion criteria for the study.

Study Design

This study was a retrospective cross-sectional study and conformed to the guidelines in the STROBE statement. After approval by the Partners Institutional Review Board (Protocol #2012P000977) for all study procedures, two physicians performed a retrospective chart review of all patients who had their first admission to MGH with MBC between 1/1/2009 and 12/31/2010.

Data Collection

We collected demographic data, including date of birth, gender, race, ethnicity, education level, and marital status, at the time of index hospital admission, through a billing database. We completed a review of the electronic medical record (EMR) to identify the dates of initial and MBC diagnosis, along with basic information about breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. The oncology team usually makes a referral to palliative care, and the EMR includes documentation of all inpatient palliative care consultations and outpatient palliative care visits. We searched the EMR for documentation of hospice utilization. We captured date of death using both the social security index and the chart review. We censored admissions and deaths after this three-year study period to standardize the follow-up time.

A physician reviewer determined the primary reason for index admission by reading the discharge summary and compared this to the principal diagnosis retrieved through the billing database. A second physician reviewed any discrepancies between the primary reason for admission as determined by the physician reviewer and the billing database, and both reviewers came to a consensus on which reason to list as the primary reason for admission. We also collected data on discharge disposition, sites of metastases, and lines of therapy administered prior to or during the hospitalization. We collected this data at index admission and at all subsequent admissions.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to describe demographic data, breast cancer-specific information, admission diagnoses, utilization of palliative care and hospice services, discharge status, and death outcomes. We used SAS software, version 9.3 for all analyses.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

We identified 123 patients hospitalized for the first time with a diagnosis of MBC (Figure 1, Table 1). The median number of hospital admissions during the three-year follow-up period was two (range, 1 to 17). All 123 patients were female with a mean age of 58 years old (SD=14) at the time of index admission. Most patients were white (80%, 99/123), married (62%, 76/123), insured, (95%, 117/123), and had at least some college education (61%, 75/123). The majority of MBC tumors were hormone receptor-positive (70%, 86/123) and HER2-negative (82%, 101/123). Twenty-eight patients (23%) had triple-negative (hormone receptor-negative, HER2-negative) tumors.

Figure 1. Screening for eligible patients.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics (n=123).

| DEMOGRAPHIC VARIABLE | |

|---|---|

| Age at index admission, mean (SD) | 58 (14) |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | |

| White | 99 (8.5) |

| Black | 6 (4.9) |

| Asian | 5 (4.1) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 3 (2.4) |

| Unavailable | 10 (8.1) |

| Partner status, No. (%) | |

| Married | 76 (61.8) |

| Single | 24 (19.5) |

| Divorced or separated | 13 (10.6) |

| Widowed | 10 (8.1) |

| Education, No. (%) | |

| ≤ High school degree | 42 (34.1) |

| Some college | 16 (13.0) |

| College or post-graduate degree | 59 (48.0) |

| Unavailable | 6 (4.9) |

| Insurance status, No. (%) | |

| Private | 72 (58.5) |

| *Medicare | 35 (28.5) |

| *Medicaid | 10 (8.1) |

| Uninsured | 6 (4.9) |

| CLINICAL VARIABLE | |

|---|---|

| Hormone receptor (HR) status of MBC, No. (%) | |

| HR-positive | 86 (69.9) |

| HR-negative | 37 (30.1) |

| HER2 receptor status of MBC, No. (%) | |

| HER2-positive | 22 (17.9) |

| HER2-negative | 101 (82.1) |

| Triple-negative MBC, No. (%) | 28 (22.8) |

| Time from initial diagnosis to MBC diagnosis, No. (%) | |

| De novo MBC (< 3 months) | 35 (28.5) |

| ≥ 3 months - 5 years | 46 (37.4) |

| > 5 years | 42 (34.1) |

| MBC diagnosis relative to index admission, No. (%) | |

| Diagnosed prior to admission | 88 (71.5) |

| Diagnosed during admission | 35 (28.5) |

| Hospital admissions, median (range) | 2 (1 to 17) |

| Index admission length of stay, median (range) | 4 (1 to 35) |

| Sites of metastases at index admission, No. (%) | |

| Bone/soft tissue | 97 (78.9) |

| Viscera | 94 (76.4) |

| Central nervous system | 32 (26.0) |

| Lines of endocrine therapy at index admission for HR+ MBC (n=86), No. (%) | |

| 0 | 43 (50.0) |

| 1 | 26 (30.2) |

| 2 | 11 (12.8) |

| ≥ 3 | 6 (7.0) |

| Lines of chemotherapy at index admission, No. (%) | |

| 0 | 57 (46.3) |

| 1 | 32 (26.0) |

| 2 | 17 (13.8) |

| ≥ 3 | 17 (13.8) |

| Treatment in the month prior to index admission, No. (%) | |

| None | 49 (39.8) |

| Chemotherapy | 45 (36.6) |

| Endocrine therapy | 18 (14.6) |

| HER2-directed therapy without chemotherapy | 7 (5.7) |

| Clinical trial | 4 (3.3) |

Medicaid and Medicare are federal health care programs. Medicaid covers low-income people who cannot afford healthcare; while Medicare applies to people who have paid into the system and reached the point of eligibility or qualify based on disability.

The time from initial breast cancer diagnosis to MBC diagnosis was less than three months in 29% (35/123), three months to five years in 37% (46/123), and more than five years in 34% (42/123) of patients. Most patients were diagnosed with MBC prior to index admission (72%, 88/123), though 28% (35/123) of patients were diagnosed with MBC during index admission. At the time of index hospitalization, 79% (97/123) of patients had bone metastases and 76% (94/123) had visceral metastases, while a minority had central nervous system (CNS) metastases (26%, 32/123).

Reasons for Index Hospitalization

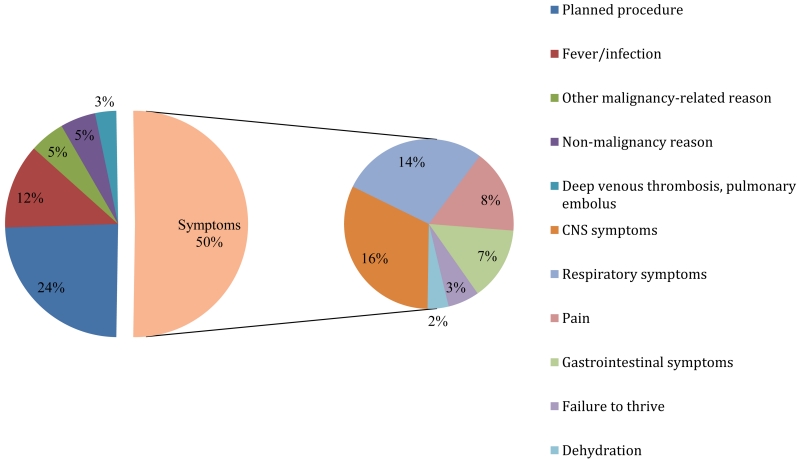

Figure 2 depicts the reasons for index hospitalization in our cohort. Uncontrolled symptoms accounted for half (50%, 62/123) of the index admissions (16% CNS symptoms, 14% respiratory symptoms, 8% pain, 7% gastrointestinal symptoms, 3% failure to thrive, and 2% dehydration). Almost a quarter of index admissions were attributable to a planned procedure (24%, 30/123), and an additional 12% (15/123) of admissions were due to fever/infection.

Figure 2. Reason for index admission (n=123).

End-of-Life Outcomes

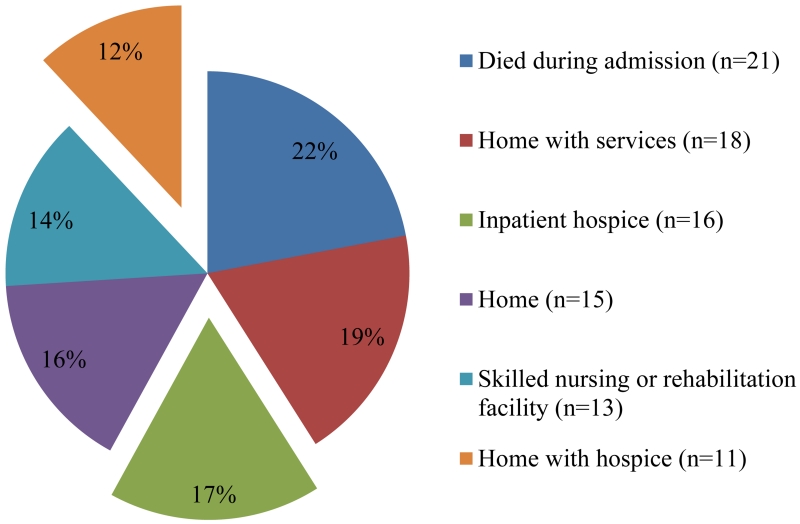

The majority of patients (76%, 94/123) died during the three year follow-up period. The median time from index admission to death was six months (range, 0 to 34 months) for all those who died during the study period and was only three months (range, 0 to 33 months) for patients admitted with uncontrolled symptoms. Among all patients who died in the study period, the median time from last hospital admission to death was nine days (range, 0 to 35 months). Approximately half (53%, 50/94) died in the hospital or within 14 days of hospital discharge. 22% (21/94) of patients died during an admission, and 17% (16/94) died while enrolled in inpatient hospice either at MGH or an inpatient facility. For the remaining patients who died during the study period, only 12% (11/94) of patients were discharged home with hospice services from their final admission (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Discharge status on last admission of those who died during the three-year study period (n= 94).

Palliative Care and Hospice Utilization

In the deceased cohort (n=94), the inpatient palliative care team evaluated 57% (54/94) of patients at least once during a hospital admission, but only 17% (16/94) of patients attended an outpatient palliative care clinic appointment throughout the study period. Additionally in this cohort, 29% (27/94) of patients were referred to hospice upon their last discharge (16/94 to inpatient hospice, 11/94 to home hospice), whereas 35% (33/94) were referred to hospice from the outpatient setting. Most of the outpatient-initiated referrals to hospice occurred after the last admission before death (85%, 28/33). The minority of patients received outpatient-initiated referrals to hospice prior to the last admission (15%, 5/33), and all of these patients died in the hospital or with inpatient hospice.

Discussion

Patients with breast cancer who are admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of metastatic disease represent a high-risk group of patients with respect to symptom burden and death. Half of patients were admitted with uncontrolled symptoms, including CNS symptoms, respiratory symptoms, pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, failure to thrive, and dehydration. Moreover, the majority of patients died during the three-year study period, with a median time from index admission to death of six months. Approximately half of these patients died in the hospital or within two weeks of discharge, which underscores the poor prognosis of patients with MBC who require hospital level care.

The medical community is well aware of the high rate in which patients with advanced cancer are admitted to the hospital during the last month of life (1). The Institute of Medicine (IOM) released the report “Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life” that draws attention to the multiple transitions between health care settings, including high rates of often preventable hospitalizations, faced by patients near the EOL (20). The IOM report also emphasizes the fact that most patients will receive acute hospital care from physicians who they have never met, underscoring the need for advance care planning to ensure that patients receive care that reflects their personal values, goals, and preferences. In order for this to occur, the IOM recommends frequent clinician-patient conversations over time. Our data points to hospitalizations as an important trigger for these conversations in patients with MBC.

In this group of patients with MBC at a high risk of death, we assessed the utilization of inpatient and outpatient palliative care and hospice services. Among those who died during the study period, the inpatient palliative care team evaluated 57% of patients at least once during an admission, but only 17% of patients attended an outpatient palliative care clinic appointment at any time during the study period. Importantly, many patients were admitted with uncontrolled symptoms and thus represent a group of patients that would likely benefit from longitudinal outpatient palliative care involvement. With the strong evidence demonstrating the benefit of palliative care in patients with metastatic cancer, many professional organizations have published guidelines to support the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care (21-23). However, timely referrals are still not commonplace for patients with MBC (24, 25), and our data reflect the lack of integration of outpatient palliative care services into the oncology care of this patient population, even at an institution with an established outpatient palliative care program.

We also found that among the subset of patients who died during the study period, less than one-third (29%) were referred to hospice upon their last discharge. Outpatient oncology clinicians referred an additional third of patients to hospice, though most of these referrals occurred after the patient’s last admission during the follow-up period. With a median survival from index hospitalization of six months, hospitalized patients with MBC are a relevant population to consider whether a hospice referral may be appropriate at discharge. Additionally, among those who died during the follow-up period, 22% of patients died during a hospital admission. Previous research demonstrates that patients with cancer who die in the hospital or ICU experience more physical and emotional distress and worse quality of life at the EOL than those who die at home with hospice (7). Though the inpatient teams may have wished to defer a hospice referral to a patient’s oncologist, a discharge without hospice services may represent a delayed or missed opportunity for earlier hospice discussions and referrals. Our data suggests that hospitalization should serve as a signal to consider whether a patient and family may benefit from a palliative care referral or hospice services and to recommend and make these referrals.

Our study adds to the published literature by describing the reasons for admission and the use of palliative care and hospice services in hospitalized patients with MBC. In one study of unplanned hospitalizations to a solid tumor oncology service at an academic hospital, the majority of patients were admitted with uncontrolled symptoms (66% of 149 admissions of 119 unique patients), with pain as the most common complaint (28%) (24). With a median survival of 3.4 months, the patients in this study had an even shorter prognosis than those in our study. This difference in median survival may be due to the inclusion of all solid malignancies in this study, many of which have a shorter prognosis than MBC. Despite the high symptom burden and poor prognosis of patients in this study, palliative care was consulted in only 6.8% of admissions, and 18% of patients enrolled in hospice upon discharge. Another study described 83 patients with MBC who were admitted to a medical oncology inpatient unit in Australia and demonstrated that only approximately 15% of admissions in 2006 received a palliative care consult (25). Our study confirms the low rates of palliative care and hospice utilization in this population. By focusing on patients hospitalized for the first time with MBC, we have identified a distinct event in these patients’ course of illness for clinicians to consider which patients may benefit from palliative care and hospice services.

There are several important limitations to our study. The study sample was comprised of a small, relatively homogeneous sample of patients, performed at a single, tertiary care center. Therefore, the findings may not be generalizable to patients with lower education and minority groups and other care settings. Second, we followed all patients for three years after their index admission and censored any data that occurred after this three-year follow-up period in order to standardize follow-up time. Although we did not collect data regarding admissions, death, palliative care, and hospice referrals that occurred outside of this study window, these data would have pertained to those patients who lived three years beyond their index admission and who had a more favorable prognosis than most of the patients in this study population. It is also important to note that there is significant variability in the roles that the oncologist, inpatient palliative care clinician, and outpatient palliative care clinician may play in a patient’s care. For example, an oncologist might consult inpatient or outpatient palliative care to address pain alone or may ask for assistance with goals of care discussions. Inpatient palliative care clinicians may find themselves speaking to patients who they have just met about EOL wishes, while an outpatient palliative care clinician may have had several visits with a patient before discussing such issues. Finally, this was a retrospective review of medical records, with all of the limitations of a chart review. It is possible that we may have missed patients who did not have an ICD9 diagnosis for breast cancer or metastatic breast cancer. We may have also missed data regarding hospice utilization if it was not documented in the EMR or a discharge summary. Additionally, patients may have been referred to outpatient palliative care but may have not attended their appointment due to sickness, admission, or death.

Hospitalized patients with MBC are commonly admitted for uncontrolled symptoms and have a poor prognosis. However, only a minority receive outpatient palliative care or are referred to hospice services from the inpatient setting. Clinicians should recognize hospitalization as a trigger to discuss values, goals, and preferences with their patients and a signal to consider whether a patient and family may benefit from a palliative care referral or hospice services. These findings highlight the need to develop interventions to improve EOL care for patients with MBC who are hospitalized.

Key statements.

What is already known about this topic

Hospitalizations in patients with metastatic cancer occur commonly at the end of life but have not been well-described in individuals with metastatic breast cancer.

Patients with metastatic breast cancer are less likely to receive hospice services when compared to those with other advanced solid malignancies.

What this paper adds

Hospitalized patients with metastatic breast cancer are commonly admitted for uncontrolled symptoms and have a poor prognosis.

Only a minority receive outpatient palliative care or are referred to hospice during their last hospitalization prior to death.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

Clinicians should recognize hospitalization as a trigger to discuss end-of-life care goals and preferences with their patients and a signal to consider whether a patient and family may benefit from a palliative care referral or hospice services.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Shin was supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health [R25CA092203].

Dr. Temel is supported by a National Cancer Institute Career Development Award [K24CA181253].

References

- 1.Goodman DC, M N, Chang C, Fisher ES, Wennberg JE. Trends in cancer care near the end of life. The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Pratice; 2013. 9/4/13. Report No. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morden NE, Chang CH, Jacobson JO, Berke EM, Bynum JP, Murray KM, et al. End-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer is highly intensive overall and varies widely. Health affairs. 2012 Apr;31(4):786–96. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0650. PubMed PMID: 22492896. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3338099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Obermeyer Z, Makar M, Abujaber S, Dominici F, Block S, Cutler DM. Association between the Medicare hospice benefit and health care utilization and costs for patients with poor-prognosis cancer. Jama. 2014 Nov 12;312(18):1888–96. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.14950. PubMed PMID: 25387186. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4274169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruera E, Russell N, Sweeney C, Fisch M, Palmer JL. Place of death and its predictors for local patients registered at a comprehensive cancer center. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2002 Apr 15;20(8):2127–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.138. PubMed PMID: 11956274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beccaro M, Costantini M, Giorgi Rossi P, Miccinesi G, Grimaldi M, Bruzzi P, et al. Actual and preferred place of death of cancer patients. Results from the Italian survey of the dying of cancer (ISDOC) Journal of epidemiology and community health. 2006 May;60(5):412–6. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.043646. PubMed PMID: 16614331. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2563975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Townsend J, Frank AO, Fermont D, Dyer S, Karran O, Walgrove A, et al. Terminal cancer care and patients’ preference for place of death: a prospective study. Bmj. 1990 Sep 1;301(6749):415–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6749.415. PubMed PMID: 1967134. Pubmed Central PMCID: 1663663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright AA, Keating NL, Balboni TA, Matulonis UA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. Place of death: correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers’ mental health. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010 Oct 10;28(29):4457–64. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3863. PubMed PMID: 20837950. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2988637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, Mack JW, Trice E, Balboni T, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. Jama. 2008 Oct 8;300(14):1665–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. PubMed PMID: 18840840. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2853806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradley EH, Prigerson H, Carlson MD, Cherlin E, Johnson-Hurzeler R, Kasl SV. Depression among surviving caregivers: does length of hospice enrollment matter? The American journal of psychiatry. 2004 Dec;161(12):2257–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2257. PubMed PMID: 15569897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kris AE, Cherlin EJ, Prigerson H, Carlson MD, Johnson-Hurzeler R, Kasl SV, et al. Length of hospice enrollment and subsequent depression in family caregivers: 13-month follow-up study. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry : official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006 Mar;14(3):264–9. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000194642.86116.ce. PubMed PMID: 16505131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cancer Facts & Figures 2015. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Earle CC, Landrum MB, Souza JM, Neville BA, Weeks JC, Ayanian JZ. Aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life: is it a quality-of-care issue? Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008 Aug 10;26(23):3860–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8253. PubMed PMID: 18688053. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2654813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Connor TL, Ngamphaiboon N, Groman A, Luczkiewicz DL, Kuszczak SM, Grant PC, et al. Hospice utilization and end-of-life care in metastatic breast cancer patients at a comprehensive cancer center. Journal of palliative medicine. 2015 Jan;18(1):50–5. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0238. PubMed PMID: 25353618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cardoso F, Di LA, Lohrisch C, Bernard C, Ferreira F, Piccart MJ. Second and subsequent lines of chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer: what did we learn in the last two decades? Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2002 Feb;13(2):197–207. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf101. PubMed PMID: 11885995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dafni U, Grimani I, Xyrafas A, Eleftheraki AG, Fountzilas G. Fifteen-year trends in metastatic breast cancer survival in Greece. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2010 Feb;119(3):621–31. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0630-8. PubMed PMID: 19915976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gennari A, Conte P, Rosso R, Orlandini C, Bruzzi P. Survival of metastatic breast carcinoma patients over a 20-year period: a retrospective analysis based on individual patient data from six consecutive studies. Cancer. 2005 Oct 15;104(8):1742–50. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21359. PubMed PMID: 16149088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiely BE, Soon YY, Tattersall MH, Stockler MR. How long have I got? Estimating typical, best-case, and worst-case scenarios for patients starting first-line chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer: a systematic review of recent randomized trials. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011 Feb 1;29(4):456–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.2174. PubMed PMID: 21189397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chia SK, Speers CH, D’Yachkova Y, Kang A, Malfair-Taylor S, Barnett J, et al. The impact of new chemotherapeutic and hormone agents on survival in a population-based cohort of women with metastatic breast cancer. Cancer. 2007 Sep 1;110(5):973–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22867. PubMed PMID: 17647245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breast Cancer Survival Rates by Stage. American Cancer Society; 2015. [updated 2/26/2015; cited 2015 March 23]. Available from: http://www.cancer.org/cancer/breastcancer/detailedguide/breast-cancer-survival-by-stage. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pizzo PA, et al. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Institute of Medicine; Washington, DC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, Abernethy AP, Balboni TA, Basch EM, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012 Mar 10;30(8):880–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161. PubMed PMID: 22312101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peters S, Adjei AA, Gridelli C, Reck M, Kerr K, Felip E, et al. Metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2012 Oct;23(Suppl 7):vii56–64. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds226. PubMed PMID: 22997455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palliative Care Version 1.2016. 2016 doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0009. Available from: www.nccn.org. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Rocque GB, Barnett AE, Illig LC, Eickhoff JC, Bailey HH, Campbell TC, et al. Inpatient hospitalization of oncology patients: are we missing an opportunity for end-of-life care? Journal of oncology practice / American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013 Jan;9(1):51–4. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2012.000698. PubMed PMID: 23633971. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3545663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Day FL, Bull JM, Lombard JM, Stewart JF. Changes in medical oncology admissions for the management of breast cancer complications: an Australian institution’s experience. Asia-Pacific journal of clinical oncology. 2011 Jun;7(2):146–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-7563.2011.01391.x. PubMed PMID: 21585694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]