Abstract

Background

Patient diaries and pain scales can capture the course and complications of pain managed at home in children. The Faces Pain Scale-Revised (FPS-R) is a validated scale showing reliability in children, but it has not been validated in children with sickle cell disease (SCD).

Objective

The purpose of this study was to evaluate comprehension and usability of an electronic modified version of the FPS-R among pediatric patients with SCD.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional, qualitative study involving in-person interviews with children/adolescents from the USA and their parents/legal guardians. Interviews involved cognitive debriefing and usability testing of the FPS-R.

Results

In total, 22 children with SCD aged 4–17 years participated. Children aged 4–6 were generally unable to demonstrate clear understanding of the FPS-R and its response scale. Overall, children aged ≥7 years understood the instrument and could complete it on the electronic device, although children aged 7–8 often needed assistance from the parent. Children aged 9–17 years were able to read and complete the instrument independently. Most participants considered the electronic device easy to use.

Conclusions

The FPS-R was shown to be a comprehensible and usable pain measure for children aged 7–17 with SCD and to be beneficial for future clinical studies.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| This is the first study to examine the Faces Pain Scale-Revised (FPS-R) to assess pain intensity in children with sickle cell disease (SCD), and the scale was shown to be a comprehensible and usable pain measure for children aged 7–17 with SCD. |

| The FPS-R will facilitate clinical research to further understanding of pain in children with SCD and will help evaluate new therapeutic options to treat pain. |

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an inherited blood disorder characterized by painful vaso-occlusive crises (VOC) that has limited treatment options, particularly for children. Prevalence estimates from a US 2008 Census ranged from 72,000 to 98,000 people in the USA alone [1].

Pain, associated with VOC, is the most common symptom in patients with SCD [2, 3] and is also the most common cause for hospitalization [4]. Painful episodes can occur without warning, and have been described as sharp, intense, stabbing, or throbbing. They often occur in the lower back, legs, arms, abdomen, and chest, and can be brought on by illness, temperature changes, stress, dehydration, and high altitudes [5].

Much of the information available on the severity and frequency of SCD pain has been collected from emergency department and inpatient admissions medical records [6]. However, since SCD pain is often managed at home [7, 8], medical records can underestimate the prevalence of SCD pain in both children [9, 10] and adults.

Patient diaries with assessment scales to measure pain can describe the course and complications of SCD pain managed at home in children and adults. Pain diaries provide a number of advantages over both retrospective interviews and reliance on medical records. In patients with SCD, recall of pain intensity experiences has been shown to be less reliable than data collected from prospective measures evaluating pain intensity [11]. Pain diaries have been used effectively by children aged 6–21 years who have SCD pain [7–10, 12], and these patients can distinguish sickle cell pain from non-sickle cell pain, such as headaches and pharyngitis [12]. Though scales can be used to collect additional information such as pain location and effects on daily living, pain diaries can capture other important information, such as the impact of SCD-related pain on a patient’s school attendance [8], ability to play sports or socialize with friends [13], and use of pain medication [14].

The validity and reliability of three pain scales has been assessed in a study of African-American children with SCD, aged 3–18 years [15]. The three scales were the African-American Oucher, Wong–Baker Scale, and Visual Analog Scale. The results of the study showed that the Wong–Baker and Oucher scales were the most valid and reliable tools for measuring pain, with the Wong–Baker scale the most preferred. However, none of these scales performed well in children aged 3–7 years. Many studies in children with SCD have utilized other pain-intensity scales, particularly components of the Adolescent Pediatric Pain Tool [16]. However, this scale was not developed and validated specifically for use in young children with SCD.

The Faces Pain Scale-Revised (FPS-R) has demonstrated acceptable measurement properties when used with children, but has not been evaluated in children with SCD [17]. The FPS-R is a single-item, patient-reported outcome (PRO) measure that was developed and tested in children aged 4–12 years to assess acute pain intensity using a paper–pencil format. Respondents select from among six faces depicting different levels of pain intensity. The PedIMMPACT (Pediatric Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials) recommended the FPS-R for assessment of acute/chronic pain in clinical trials targeting children aged 4–12 years [18]. The FPS-R was also recommended by experts in a consensus paper outlining pediatric analgesic clinical trial designs [19]. A recent systematic review of faces scales [20] has recommended the FPS-R for research use in children on the basis of utility and psychometric features. The validity and acceptability of the FPS-R has also recently been demonstrated in research conducted in East Africa [21]. This evidence suggests the FPS-R may be valuable for assessing pain in children with SCD.

The FPS-R may also be suitable for use in an electronic pain diary. A study using the Faces Pain Scale—the precursor to the FPS-R—in children with chronic pain from headaches or juvenile idiopathic arthritis showed e-diaries provided significantly greater compliance and accuracy than paper diaries over a 7-day period [22]. Other studies using different pain scales have shown support for the use of hand-held e-diaries to capture characteristics of daily pain in children with SCD [23, 24]. Thus, an electronic pain diary utilizing the FPS-R may be particularly useful to assess daily pain in children with SCD.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate comprehension and usability of a modified electronic version of the FPS-R for pediatric patients aged 4–17 years enrolled in a phase III SCD study. Modifications included revised instructions and item content, which asks the patient to consider their amount of sickle cell pain today and rate their worst pain today. Qualitative interviews were conducted with patients and their respective parent/legal guardian.

Methods

Study Design

This was a cross-sectional, qualitative study involving one-time face-to-face interviews with children/adolescents from the USA and their parent/legal guardian. Interviews involved both cognitive debriefing and usability testing of an electronic version of the FPS-R. The sample was stratified according to age: patients aged 4–5, 6–11, and 12–17 years. The lower end of the age range was oversampled, given the greater uncertainty about the ability of younger children to understand and complete the scale.

Eligibility Requirements and Recruitment

Participants were required to meet all the following criteria to be eligible for the study: aged ≥4 to <18 years and diagnosed with SCD (laboratory-determined HbSS or HbS beta zero thalassemia), experienced SCD-related pain within the past 12 months, and those aged ≥12 willing and able to sign a study assent form. Additionally, eligibility was based on the parent/legal guardian being aged ≥18 years, willing and able to complete a study questionnaire and to be present at and/or participate in a face-to-face interview with the child.

Participants were excluded if they were unable to cooperate with interview procedures; if the parent/legal guardian had a psychiatric, cognitive, or other impairment that would interfere with the ability to provide written informed consent and/or participate in the study procedures or interfere with the interpretation of the study results.

Eligible participants were identified by reviewing existing market research participant panels comprising individuals who have agreed to be contacted about participating in research studies. Participants were also recruited through referrals from physicians and patient advocacy groups. For all recruitment strategies, the parents/legal guardians of potentially eligible participants were contacted by phone, mail, email, or in-person and were provided with a brief description of the study. Interested individuals were screened via telephone or in-person to confirm eligibility and interest in study participation, and to also collect sociodemographic and clinical information, such as age and sex of the child, in an effort to recruit a diverse sample.

Modifications to the Faces Pain Scale-Revised (FPS-R)

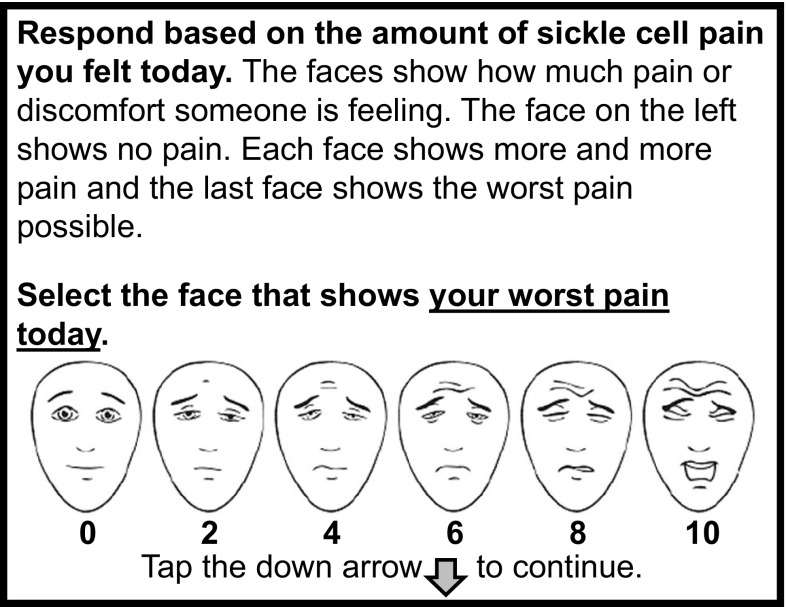

In this study, a modified version of the FPS-R (Fig. 1) was used. Respondents selected from among the six faces depicting increasing levels of pain intensity (from left to right) as used in the original FPS-R, with the score options 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 shown below each face. As in the original measure, intermediate score response options (e.g., 1, 3, 5, 7, 9) were not possible. The scale was modified to be appropriate for use in patients with SCD in a clinical trial setting. This included modifying the instructions slightly to reflect the meaning of the response scale anchors continuum as “worst pain possible,” which may be more reliable in a clinical trial setting to assess chronic pain [25] than the original description, “shows very much pain.” Additionally, given that SCD pain is not consistent throughout the day and can vary from time to time [26], the original FPS-R item construct and recall period was modified from “shows how much hurt you are having right now” to “shows your worst pain today.” Lastly, the scale was modified to ask participants to report on pain related to SCD.

Fig. 1.

Modified Faces Pain-Scale Revised (FPS-R). http://www.iasp-pain.org/FPSR. Copyright ©2001, International Association for the Study of Pain®, reproduced with permission

Study Procedures

An electronic hand-held device with a touch screen and stylus (the Pidion BM-170: eResearch Technology, Inc., Philadelphia, PA, USA) that allows subjects to answer questionnaires in a format similar to paper was utilized. After patients were given instructions on how to use the device, they were asked to complete an electronic version of the FPS-R. Children who were unable to read or needed guidance on how to complete the FPS-R received assistance from the parent/legal guardian. The parent/legal guardian could read the instructions on the screen (Fig. 1) to help the child understand the meaning of the item and scale, but they were instructed not to help their child decide on or select a response.

In instances where the child participant was unable to complete the FPS-R, or if their understanding of the item or response scale was uncertain, an alternative instruction set was provided to the parent/legal guardian (Table 1). These alternative instructions provided a standardized, simplified guide for parents to aid in instructing their children on use of the tool without helping their child decide which answer to choose.

Table 1.

Alternative instructions—revised

| Please read the following information to your child or have your child read it: |

| ● These faces (point to faces on screen) show how much pain or hurting someone is feeling because of their [sickle cell disease or other term you use with your child to refer to his/her disease] |

| ● This face here (point to far left face) shows a person who doesn’t have any pain or hurting |

| ● Each face shows more and more pain or hurting (point to second, third, fourth and fifth face) |

| ● (Point to far right face) This face here shows a person who has the worst pain or hurting |

| ● Now think about today and how much pain or hurting you’ve been having today because of [sickle cell disease or other term you use with your child to refer to his/her disease] |

| ● Sometimes pain and hurting can get better or worse during the day. Think about today and when your pain or hurting was at its worst today |

| ● Now show me the face that shows how much pain or hurting you had today when it was at its worst |

After completing the FPS-R, cognitive debriefing interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide. Selections from the interview guide are presented in Table 2. Participants answered a series of questions about the FPS-R instructions, item stem and response options to assess their understanding of the item (what the respondent believed the item was asking), the meaning of terms (what specific words and phrases meant to the respondent), and fit and adequacy of the response scale [27]. Parents were asked questions pertaining to the original and alternate instructions for the scale. Children were asked about their pain experience, and parents were asked to describe observations regarding their child’s pain experience. Patients and their parents also provided their impressions regarding completion of the instrument on the electronic device.

Table 2.

Selections from the Interview Guide

| 1. Cognitive debriefing questions |

| ● Have you had any pain or hurting today? |

| ● When you answered this question, you chose this face [point to face by child]. How do you think this person is feeling? How much pain is this person having?—REPEAT THIS FOR ALL FACES |

| ● When is the last time you had pain or hurting? Can you tell me about that time? Now can you point to the face that shows how much pain or hurting you were having that time? |

| ● Have you heard the word “discomfort” before? If yes, what does “discomfort” mean? |

| 2. Usability testing questions for parent and child |

| ● Could you see all the faces clearly on the screen? |

| ● Would you be willing to use the small computer again to answer questions about your pain? |

| 3. Questions for the parent/legal guardian relating to the original instructions |

| ● How well did your child understand the instructions you gave him/her? |

| ● How confident are you that your child understood the response scale? |

| ● If your child had to complete this each night, do you think your child would be able to think back over the course of the day and indicate his/her worst pain using this scale? |

| 4. Questions for the parent/legal guardian relating to the alternate instructions (if applicable) |

| ● Did the alternative instructions help instruct your child on what to do? |

| ● How confident are you that your child understood the question? |

| ● If your child had to complete this each night, do you think your child would be able to think back over the course of the day and indicate his/her worst pain using this scale? |

| 5. Indicators of pain |

| ● Can you tell me about your child’s pain related to sickle cell disease? |

| ● Can you tell when your child is experiencing pain related to sickle cell disease? How can you tell? What do you observe? |

The first interview of this study occurred on 25 November 2013, and the last interview occurred on 18 October 2014. Local institutional review board approval was obtained from all participating sites. All study sites were located in the USA, with interviews conducted in Philadelphia, Atlanta, Dallas, Los Angeles, and Chicago.

Data Analyses

All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were reviewed and de-identified to ensure confidentiality. Data from the transcripts were organized using a qualitative software tool, MAXQDA 11. Codes were developed based on the questions asked, and responses from the participants were organized by applying the codes to the responses. Data were reviewed to assess how well participants understood the FPS-R and whether any issues related to usability were identified. Sociodemographic data were collected and summarized using descriptive statistics. Frequencies and percentages were calculated for the categorical variables.

Results

Demographics and Pain Characteristics

In total, 22 children/adolescents aged 4–17 years participated, which included seven children aged 4–5 years, 12 aged 6–11 years, and three adolescents aged 12–17 years. One was White, two were Hispanic, and the remaining were African American. The sample included 13 females and nine males. Current educational grade level ranged from pre-kindergarten to kindergarten in the group aged 4–5 years, from grades 1 to 6 in the group aged 6–11 years, and from grades 7 to 12 in the group aged 12–17 years. Most of the children (n = 18) were very familiar with touchscreen devices such as smart phones and tablets, and most parents (n = 16) reported they were very confident in their children’s ability to use these devices.

In the group aged 4–5 years, three children were able to provide descriptions of their last experience of pain. Eight children aged 6–11 years provided some description of their experiences with pain, although some had difficulty remembering past experiences of pain or trouble articulating the feeling of pain for each of the six faces. Three children in this age group reported that, as their pain increased they become less mobile and might need medicine or require hospitalization. In the oldest age group, all patients were able to give detailed descriptions of pain and reported that increasing pain was associated with decreased physical function and may require medication.

In all age groups, leg pain was most commonly reported (77 % of patients), with a decreased ability to walk when in pain. Children/adolescents in the two older age groups also reported pain in their arms and back. Parents of all age groups reported their children becoming lethargic and less active when experiencing pain, and verbalizing their pain through crying/screaming. Some children aged 4–5 years were able to provide descriptions of their last experience of pain. One child described feeling “horrible” (4 years), another as feeling “angry” (5 years), and a third as feeling “hurting … and it was hot” (4 years). Other quotes, as told by the children’s parent/caregiver, included statements that pain feels “like somebody hit him with something” or “like a crushing feeling” (4 years), and a 5 year old not liking to talk about her pain “cause she doesn’t like to go to the hospital.” In the two older age groups, patient-reported descriptions at varying levels of pain were obtained and are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Patient-reported descriptions of pain (ages 6–11 years)

| Descriptions of pain | Patient quotes |

|---|---|

| Mild pain experience Pain level 0–2 |

“[For prior experience of a little pain] a 2 or a 4 … I didn’t have to go to the hospital.” [age 7] “[2 felt like] My leg was hurtin’ like right here but it wasn’t hurtin’ that bad.” [age 10] “[Mild pain is] like, it don’t hurt that much and I can still move around.” [age 10] “[Mild pain is like] someone pushed me into a wall.” [age 11] “[Prior experience of a little pain (2) was] like I have fallen onto a rock.” [age 11] |

| Moderate pain experience Pain level 4–6 |

“[Prior experience of pain (4)] wasn’t really, like, pleasant.” [age 9] “[Prior experience of a little pain (4)] wasn’t that bad. I could still do things and I could get up and do some stuff instead of just laying around all day.” [age 9] “[Moderate pain is] when I need to take medicine and it’s hurtin’ a little bit.” [age 10] “[Moderate pain is like] When someone kicks me real hard.” [age 11] |

| Severe pain experience Pain level 8–10 |

“[Last experience of pain was like] I couldn’t crawl. I couldn’t crawl or walk and I wasn’t feeling good. My legs were hurting six. Stomach hurting six. Back hurting really large [pointed to 10].” [age 6] “It’s like somebody’s in my stomach kicking me and hitting me.” [age 7] “[Last experience of pain (10)] I was feeling bad and it felt … and I didn’t want anybody to touch me and … and it … and, uh, I … I … I couldn’t move my arms ‘cause they were swole’” [age 7] “[Regarding last experience of pain (10)] I don’t really wanna talk about it … [Face 10] wants his Mommy.” [age 7] “[Prior experience of pain 10 was] A pain crisis … I was screaming.” [age 8] “[Worst experience of pain (10) was like] It was hurting a lot and it didn’t feel right in my body because of how much it hurted.” [age 9] “[Severe pain is] when I have to go to the hospital.” [age 10] “[Severe pain is like] I drop to the floor really hard.” [age 11] “[Worst experience of pain (10)was like] I was getting stabbed in the back” [age 11] |

Table 4.

Patient-reported descriptions of pain (ages 12–17 years)

| Descriptions of pain | Patient quotes |

|---|---|

| Mild pain experience Pain level 0–2 |

“Yes, um, when I have a little pain (2) it just feels like … I probably … I will get hot sometimes or … and my heart starts beating fast like if I was playing football or basketball, I’ll start to get hot or … and my heart will start beating fast.” [age 12] “Well, um, when you have a little pain [2], it’s little. Just like it’s … it’s little. Um, you can still function. You can still talk. You can still do things. You know, you know it’s there but it’s not affecting you, you know, physically. It’s not affecting you mentally. You’re still able to function. Um, so that’s the way I … I think a little pain, you know, you’re … you know it’s there. It’s hurting a little bit but you’re still able to go on with your life and still do what you like to do.” [age 15] “[2 feels like] for instance like on a regular school day, maybe I’ll experience pain and fatigue, um, pain about twice a day and it’s not that bad.” [age 17] |

| Moderate pain experience Pain level 4–6 |

“[Regarding prior experience with pain at 4] Um, it hurted a lot but it didn’t hurt as much as like his face [10] … Well, it hurted sometimes, and then sometimes it won’t, and then it will come back again, and I’ll feel better. Then it will hurt and then I’ll just feel better.” [age 12] “When it’s above a five, to me, it makes a lot of things go down for you. Like when I’m in school and I have pain and it’s above a five then it becomes hard for me to function and hard for me to pay attention in class because it’s just … constant and … it’s pretty often. When I have pain, I have to go home.” [age 15] “Mmm, I’d say a six is like you can … well, at least for me, I can still bear it but it’s … it’s like you don’t really want to … you don’t have that much drive to do as much as you usually would because, you know, the pain is kind of dragging you down a little bit at that point.” [age 17] |

| Severe pain experience Pain level 8–10 |

“[Severe pain] will hurt a lot.” [age 12] “[Worst pain possible means] Like if it’s a ten, it’s … it can’t go any higher than a ten. It’s just you can’t take it anymore. It’s very painful. It’s excruciating and it’s … it’s, you know, it’s nothing else that you can do about it. It’s just the worst pain like you can’t do anything about it.” [age 15] “And about 20 min later, it went from a four to a ten. And both of my legs were hurting and my back and I couldn’t walk. I was screaming and hollering. I thought I needed an ambulance. It just increased like it can just go up like instantly.” [age 15] “[Regarding prior experience with pain at 10] Well, to me, once it gets higher than a five and it keeps escalating, m … medicine doesn’t really help me. I have to go to the emergency room. Now when I get to the emergency room, yes, medicine helps. But it’s fluids and morphine and things like that. It’s more medicine, you know, it’s more powerful medicines or stronger medicines that help the pain go down but even sometimes when you get the medicine, it doesn’t really cut the pain.” [age 15] “[Worst pain possible means] It’s constant and it’s at a ten. Like pretty much the whole day and over several days.” [age 17] “[Regarding experience with pain at 10] I guess I’m kind of used to it like I usually go to the hospital about once a year so that’s that … um, I guess you could say once a year kind of pain. You … when you have to go to the hospital and get pain medicine so definitely not a happy or fun time at all.” [age 17] |

Children Aged 4–5 Years

Children in the group aged 4–5 years generally did not have a clear understanding of the FPS-R and how to use the response scale. Most children in this age group were not familiar with the term “discomfort,” and many did not know the meaning of the term “pain.” It was unclear whether these children were able to consider their worst pain over the course of the day and respond accordingly. From the interviewer impression, it was generally difficult to ascertain the children’s level of understanding because of their limited language, limited attention span, or the influence of the parent. Nevertheless, one parent reported that the scale enabled her child to better explain and show his pain.

Understanding the FPS-R and Instructions

Of the seven participants in this age group, four did not understand the word “pain” and five did not understand the word “discomfort,”; however, all understood the term “hurt.” The children were often unable to articulate the level of pain intensity shown by each face on the scale. For example, when asked how much pain the face labeled “2” has, one 4 year old responded “2 feelings,” and for the face labeled 4, she responded “4 feelings.” In some cases, the children were unable to articulate the differences in pain represented by each face. For example, one 5 year old appeared to understand the general ordering of the scale but was unable to describe the differences between several of the faces, reporting the faces labeled 2, 4, and 6 each represented “a little pain” and faces labeled 8 and 10 each represented “a lot of pain.” Children were asked which response they would choose if they had no pain, little pain, lot of pain, and the worst pain; the results are presented in Table 5. Six of the seven children gave at least one response that was incorrectly ordered and not reflective of the intended level of pain. Additionally, one child initially selected the face labeled “2” for “worst pain face,” but changed their selection to the face labeled “10” after coaching by their parent, and one child did not select a face for either “a lot of pain” or “worst pain.”

Table 5.

Children’s pain face number responses if they had “no pain,” “a little pain,” a lot of pain,” and “worst pain” (ages 4–5 years)

| Patient ID | Age | Pain faces | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No pain | A little pain | A lot of pain | Worst pain | ||

| 101 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 2a,b |

| 102 | 4 | 4b | 2 | No response | No response |

| 301 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 0b |

| 306 | 4 | 10b | 0b | 6 | 10 |

| 302 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 10 |

| 305 | 5 | 10b | 2 | 8 | 10 |

| 403 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 10b | 6b |

aPatient selected face 10 after being coached by parent

bReflects incorrect order of responses

All children required assistance from the parent/legal guardian to complete the FPS-R. Rather than reading the instruction to their child verbatim, parents generally paraphrased the instruction using terms they believed their child would understand. In many cases, the parent omitted important elements of the instruction, such as that pain was supposed to be rated at its “worst” or that the item was specific to SCD pain. Four of the parents also “coached” their child into what they considered an appropriate response. Thus, in all cases, children in this group were able to provide an answer, but the degree to which they truly understood the question and the response scale was difficult to ascertain.

Feedback on the Instructions and Device

Most parents thought it was easy to instruct their child using the original instructions; however, a few reported some difficulty. One parent reported difficulty explaining the meaning of the response options in terms that their child would comprehend. Two parents pointed out that some of the face depictions were quite similar, which made it challenging to explain the differences to their child.

All parents reported that the alternate instructions were easy to understand and more explanatory than the original instruction, although one parent reported a preference for the original instructions, noting that the alternate instructions were wordy. In general, parents thought the alternative instructions were more helpful because they provided a more detailed explanation of the response scale.

Both parents and children thought the device was easy to use. All parents and all but one child reported being able to see the faces clearly on the screen.

Children Aged 6–11 Years

Most children in this age group were able to demonstrate an understanding of the FPS-R and how to use the response scale. Two of the three 6-year-old participants did not show a clear understanding of the scale. All children aged 7–11 years understood and could use the scale.

Understanding the FPS-R and Instructions

One 6 year old and one 7 year old did not understand the term “pain” and instead used “hurting” to describe this symptom. None of the 6 year olds knew the term “discomfort” and only one of four 7 year olds and one of two 8 year olds understood the term. Two of the 6-year-old children did not seem to understand the concept of “worst pain.”

Children in this group generally understood the ordering and direction of response categories and were able to discern between them. For instance, when asked to compare faces, children were generally able to accurately indicate which face demonstrated more pain along the continuum. Some had difficulty finding the words to articulate the level of pain represented by each face. For instance, a 6 year old reported that the face labeled “2” was “sleepy” and that the face labeled “4” was “tired.” Some participants tried to find meaning in the numbers below the faces. For example, when asked how much pain “Face 6” was having, one 7 year old responded “6 percent pain.” When asked which response they would choose if they had no pain, a little pain, a lot of pain, and the worst pain, one 6 year old selected a lower face (face labeled 4) for “worst pain” than they did for “a lot of pain” (face labeled 6), and four children in the age group chose the face labeled “4” for “lot of pain” (Table 6).

Table 6.

Children’s pain face number responses if they had “no pain,” “a little pain,” a lot of pain,” and “worst pain” (ages 6–11 years)

| Patient ID | Age | Pain faces | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No pain | A little pain | A lot of pain | Worst pain | ||

| 502 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 10 |

| 601 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 4a |

| 604 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 10 |

| 602 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 10 |

| 603 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 10 |

| 605 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 10 |

| 606 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 10 |

| 401 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 10 |

| 402 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 6 | 10 |

| 304 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 10 |

| 105 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 10 |

| 104 | 11 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 10 |

aReflects incorrect order of responses

All children aged 6–8 years required at least some level of assistance from the parent/legal guardian to complete the FPS-R, with the exception of one 7 year old who was able to complete it independently. In general, assistance was provided because the child needed some level of help reading the item. As with parents of younger children, parents of those needing assistance sometimes paraphrased the instruction using terms that they believed their child would understand. However, in such cases, the parent often omitted important elements of the instruction or misinterpreted the question themselves and therefore did not ask the correct question.

All children aged 9–11 years (n = 3) and one 7 year old understood the instructions and were able to complete the question on their own without assistance.

Eight children between the ages of 6 and 8 were given the alternative instructions for completion of the FPS-R, and five of the children gave a different and more accurate response than the one they gave using the original instructions, which included the one patient who initially selected the wrong face for “worst pain.” The alternative instructions generally improved participants’ comprehension of the scale and the distinction among faces.

Feedback on the Instructions and Device

All but one parent who provided assistance thought it was easy to instruct their child using the original instructions. Parents reported that the alternate instructions were easy to understand and more explanatory than the original instruction. However, one parent of an 8 year old thought the alternate instructions were leading and that the children should interpret the faces on their own.

In general, both parents and children thought the device was easy to use. All participants reported being able to see the faces clearly on the screen.

Children Aged 12–17 Years

All three adolescents interviewed in the group aged 12–17 years demonstrated a clear understanding of and ability to use the FPS-R.

Understanding the FPS-R and Instructions

Adolescents in the group aged 12–17 years had no difficulty understanding words in the instructions or the meaning of the item and response scale. They were able to complete the FPS-R independently.

All adolescents in this age group understood the ordering and direction of the response categories and were able to distinguish between the faces. They were able to demonstrate a clear understanding of the level of pain represented by each face, and were able to use the response option continuum appropriately to show their worst pain for that day. When asked which response they would choose if they had no pain, little pain, lot of pain, and the worst pain (Table 7), they all demonstrated an ability to use the scale appropriately.

Table 7.

Children’s pain face number responses if they had “no pain,” “a little pain,” a lot of pain,” and “worst pain” (ages 12–17 years)

| Patient ID | Age | Pain faces | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No pain | A little pain | A lot of pain | Worst pain | ||

| 303 | 12 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 10 |

| 201 | 15 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 10 |

| 202 | 17 | 0 | 6 or 8 | 8 | 10 |

All patients interpreted the instructions as intended, and alternate instructions were not required.

Feedback on the Instructions and Device

All participants reported that the instructions were clear and easy to understand, but suggested the color of the arrow in the electronic device should be stated in the instructions.

Discussion

This study evaluated the ability of children aged 4–17 years with SCD to understand and complete the FPS-R to assess pain intensity. This study also examined use of the FPS-R on an electronic device in children, similar to other studies, including the original Faces Pain Scale [22, 28, 29]. Cognitive interviews were conducted to assess participant understanding of instructions, response option content, the ordering and direction of response categories, and participant ability to select a response using the electronic device, and to explore participants’ experience of SCD pain.

Most children aged 4–6 years were unable to demonstrate a clear understanding of and ability to use the scale, suggesting that children in this age range with SCD may be unable to provide valid and reliable responses to this item. These findings are generally consistent with the findings of von Baeyer and colleagues [30, 31], as well as with those reported in the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Task Force Report on pediatric PRO assessment [32], which suggests that children aged >8 years may not be able to reliably self-report. Additionally, parents of children in this age range tended to paraphrase the question for their child and provided substantial assistance to elicit a response, often correcting the child and coaching them into what they considered a correct response.

By the age of 7–8 years, children with SCD in this sample appeared to have a clear understanding of the question, the response option continuum, and the ordering of responses. However, parents of children aged 7–8 years typically needed to provide some assistance reading or rephrasing the item, particularly because some terms (e.g., discomfort) were not always understood. All children aged 7–8 years understood the term “worst pain.” Since some children had not experienced pain on the day of the interview, it was difficult to determine their ability to rate the worst pain that they had in a single day. Also, parents who provided assistance by paraphrasing the question often left out the instruction to provide a rating based on worst pain associated with SCD.

All children aged ≥9 years in this study were able to read the instructions and item content independently and respond to the item independently.

Given the numerous versions of the FPS-R available, the authors chose a scale that employed a 0–10 numbering system, in line with the “common metric” as indicated by Hicks et al. [17]. Most participants understood the response option directionality, and, notably, some of the younger children tried to assign meaning to the numbers under the faces. For example, one child described that the “2” represented “2 feelings”, while another described that the “6” represented “6 percent pain.”

A more detailed set of standardized instructions was developed for parents of children who needed assistance reading or understanding the item. In general, parents considered this alternative set of instructions helpful in explaining the item and response scale to their child. Parents generally felt that the alternative instructions would better allow them to elicit an accurate response from their child. This was particularly helpful to children as young as 7–8 years old.

The device itself was generally considered easy to use, with no major usability issues. Given the simplicity of the scale, the short length of time needed to complete it, and its suitability to capture “worst” pain over the course of a day, it is an acceptable tool to employ in an ongoing clinical trial of an investigational agent to reduce SCD pain frequency.

There were a number of limitations to this study. The sample size was modest and limited to a subset of certain types of SCD (HbSS or HbS beta zero thalassemia). The study sample was largely drawn from African-American English-speaking individuals living in large US metropolitan areas, thereby making it difficult to generalize these findings to other populations. The inclusion criteria for occurrence of SCD pain was very broad, since limiting the sample to those children with very recent pain to improve recall reliability (e.g., in the previous week) would have made it logistically very difficult to schedule interviews. Further, some children might still have been receiving analgesics. A design requiring very recent pain also would have excluded the youngest SCD children who were the focus of this study, as these young children typically do not have frequent pain. The inclusion of parents in the interviews could have influenced some of the children’s responses. Lastly, while comprehension and usability of the FPS-R was ongoing, the scale was also being utilized as part of a phase III SCD study. As a result, during the cognitive testing process of this study, if a term was not understood, revisions to the instrument were not made (e.g., revising some of the terms such as “discomfort”), but rather the alternate set of instructions was used.

Practical considerations limited our ability to test revised instructions and item content in this particular cognitive testing study. Future research should evaluate a single set of simplified instructions based on the alternate instructions tested in this study and test terms that may be better understood across age groups (e.g., “hurt” vs. “pain” or “discomfort”). Also, for those children who cannot read well but are able to understand and select a response option on their own, instructions that are read to children verbatim (i.e., in the form of an interviewer-administered survey versus paraphrased instructions) are important for ensuring standardization of instrument administration.

Conclusion

The FPS-R, when used with the alternative instructions where parental assistance is needed, is appropriate for children aged ≥7 years with SCD, will facilitate clinical research to further understanding of pain in children with SCD, and will help evaluate new therapeutic options to treat pain. For the future of psychometric evaluation, a continued focus on demonstrating validity, reliability, and ability to detect meaningful change in pain scales would be recommended.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Jean Paty for his advisement on the conduct of this research study, Dr. Anindita Sen for her interpretation of the results from a regulatory perspective, and all patients who participated in the study.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

This study and the writing of this paper were funded by Daiichi Sankyo Company, Ltd. and Eli Lilly and Company. N. Gupta, A. N. Naegeli, and L. E. Heath are employees of Eli Lilly and Company; D. M. Turner-Bowker was an employee of ERT at the time the study was conducted, and received funding to conduct the study; E. M. Flood is an employee of ICON and received funding to conduct the study; S. M. Mays and C. Dampier are employees of Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta and both received funding to conduct the study.

Ethical Standards

The study was approved by the New England Institutional Review Board (IRB# 13-372: 2535-0019) and the Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta IRB (IRB# 14-154) and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent

All parents/legal guardians were required to provide written informed consent for their/their child’s participation in the study. Children provided assent per local IRB guidelines.

Contribution of Each Author

N. Gupta contributed to the study data analysis, interpretation of results, and writing of the manuscript. A. N. Naegeli and L. E. Heath contributed to study design, study data analysis, interpretation of results, and writing of the manuscript. D. M. Turner-Bowker, E. M. Flood, and S. M. Mays contributed to the study design and conduct, study data analysis, interpretation of results, and writing of the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hassell KL. Population estimates of sickle cell disease in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:S512–S521. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sickle Cell Disease: Complications and Treatments. Centers for Disease Control. 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/sicklecell/treatments.html. Accessed 3 Aug 2015.

- 3.Platt OS, Thorington BD, Brambilla DJ, Milner PF, Rosse WF, Vichinsky E, et al. Pain in sickle cell disease. N Eng J Med. 1991;325:11–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199107043250103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ballas SK, Lusardi M. Hospital readmission for adult acute sickle cell painful episodes: frequency, etiology, and prognostic significance. Am J Hem. 2005;79:17–25. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NIH. What are the signs and symptoms of sickle cell disease? National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. 2015. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/sca/signs. Accessed 7 Feb 2016.

- 6.Smith WR, Bovbjerg V, Penberthy L, McClish D, Levenson J, Roberts J, et al. Understanding pain and improving management of sickle cell disease: the PiSCES Study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97:183–193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuggle P, Shand PAX, Gill LJ, Davies SC. Pain quality of life, and coping in sickle cell disease. Arch Dis Child. 1996;75:199–203. doi: 10.1136/adc.75.3.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shapiro BS, Dinges DF, Orne EC, Bauer N, Reilly LB, Whitehouse WG, et al. Home management of sickle cell-related pain in children and adolescents: natural history and impact on school attendance. Pain. 1995;61:139–144. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00164-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dampier C, Ely B, Brodecki D, O’Neal P. Characteristics of pain managed at home in children and adolescents with sickle cell disease by using diary self-reports. J Pain. 2002;3:461–470. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2002.128064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dampier C, Ely EB, Brodecki D, O’Neal P. Home management of pain in sickle cell disease: a daily diary study in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2002;24:643–647. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200211000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith WB, Safer MA. Effects of present pain level on recall of chronic pain and medication use. Pain. 1993;55:355–361. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90011-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dampier C, Ely EB, Eggleston B, Brodecki D, O’Neal P. Physical and cognitive-behavioral activities used in the home management of sickle pain: a daily diary study in children and adolescents. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2004;43:674–678. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McClish DK, Smith WR, Dahman BA, et al. Pain site frequency and location in sickle cell disease: the PiSCES Project. Pain. 2009;145:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maikler VE, Broome ME, Bailey P, Lea G. Childrens’ and adolescents’ use of dairies for sickle cell pain. JSPN. 2001;6:161–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2001.tb00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luffy R, Grove SK. Examining the validity, reliability, and preference of three pediatric pain measurement tools in African-American children. Pediatr Nurs. 2003;29:54–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernandes AM, De Campos C, Batalha L, Perdigão A, Jacob E. Pain assessment using the adolescent pediatric pain tool: a systematic review. Pain Res Manag. 2014;19:212–218. doi: 10.1155/2014/979416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford PA, van Korlaar I, Goodenough B. The Faces Pain Scale revised: toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain. 2001;93:173–183. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGrath PJ, Walco GA, Turk DC, Dworkin RH, Brown MT, Davidson K, et al. Core outcome domains and measures for pediatric acute and chronic/recurrent pain clinical trials: PedIMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008;9:771–783. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berde CB, Walco GA, Krane EJ, Anand KJ, Aranda JV, Craig KD, et al. Pediatric analgesis clinical trial designs, measures, and extrapolation: report of an FDA scientific workshop. Pediatrics. 2012;129:354–364. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomlinson D, von Baeyer CL, Stinson JN, Sung L. A systematic review of Faces scales for the self-report of pain intensity in children. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1168. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang KTL, Owino C, Vreeman RC, Hagembe M, Nijuguna F, Strother RM, et al. Assessment of the face validity of two pain scales in Kenya: a validation study using cognitive interviewing. BMC Palliat Care. 2012;11:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-11-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palermo TM, Valenzuela D, Stork PP. A randomized trial of electronic versus paper pain diaries in children: impact on compliance, accuracy, and acceptability. Pain. 2004;107:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacob E, Stinson J, Duran J, Gupta A, Gerla M, Ann Lewis M, et al. Usability testing of a smartphone for accessing a web-based e-diary for self-monitoring of pain and symptoms of sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34:326–335. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318257a13c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McClellan CB, Schatz JC, Puffer E, Sanchez CE, Stancil MT, Roberts CW. Use of handheld wireless technology for a home-based sickle cell pain management protocol. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34:567–573. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atkinson TM, Mendoza TR, Sit L, Passik S, Scher HI, Cleeland C, et al. The Brief Pain Inventory and its “Pain At Its Worst in the Last 24 Hours” item: clinical trial endpoint consideration. Pain Med. 2010;11:337–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00774.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith WR, Scherer M. Sickle-cell pain: advances in epidemiology and etiology. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2010;2010:409–415. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2010.1.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tourangeau R. Cognitive sciences and survey methods. In: Jabine T, Straf M, Tanur J, Tourangeau R, editors. Cognitive aspects of survey methodology: building a bridge between disciplines. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1984. pp. 73–100. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wood C, von Baeyer CL, Falinower S, Moyse D, Annequin D, Legout V. Electronic and paper versions of a faces pain intensity scale: concordance and preference in hospitalized children. BMC Pediatr. 2011;12:87. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-11-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun T, West N, Ansermino JM, Montgomery CJ, Myers D, Dunsmuir D, et al. A smartphone version of the Faces Pain Scale-Revised and the Color Analog Scale for postoperative pain assessment in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2015;25:1264–1273. doi: 10.1111/pan.12790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.von Baeyer CL, Forsyth SJ, Stanford EA, Watson M, Chambers CT. Response biases in preschool children’s ratings of pain in hypothetical situations. Eur J Pain. 2009;13:209–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.von Baeyer CL, Uman LS, Chambers CT, Gouthro A. Can we screen young children for their ability to provide accurate self-reports of pain? Pain. 2011;152:1327–1333. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matza LS, Patrick DL, Riley AW, Alexander JJ, Rajmil L, Pleil AM, et al. Pediatric patient-reported outcome instruments for research to support medical product labeling: report of the ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices for the Assessment of Children and Adolescents Task Force. Value Health. 2013;16:461–479. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]