Abstract

Background

In men with prostate cancer (PCa) large variations of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) after radical prostatectomy (RP) or high-dose radiotherapy (RAD) may be related to between-country differences of pre-treatment medical and socio-demographic variables, as well as to differences in pre-treatment PROs in the sexual and urinary domain.

METHODS

In 1908 patients with localized PCa from Norway, USA or Spain the relation was investigated between pre-treatment data on medical (PSA, Gleason score, cT-category ) and socio-demographic variables (age, education, marital status). Using the EPIC questionnaire pre-treatment PROs within the sexual and urinary domain were also considered.

RESULTS

Compared to the European patients American patients were younger, fewer had co-morbid conditions and more had a high education level. Fifty-three % of the US-men eligible for RP had low-risk tumors compared to 42% and 31% among respectively the Norwegian and the Spanish patients. Among the Spanish RAD patients 54% had had low- risk tumors compared to respectively 34% of the American and 21% of the Norwegian men planned for RAD. Compared to the European patients significantly fewer US patients reported moderate or severe sexual dysfunction and related problems. In most subgroups the number of patients with sexual or urinary dysfunctions exceeded that of patients with bother related to the reported dysfunction.

CONCLUSIONS

Statistically significant between-country differences were observed in pre-treatment medical and socio-demographic variables, as well as in pre-treatment PROs within the sexual and urinary domain. Large differences between reported dysfunction and related problems within the sexual and urinary domain indicate that dysfunction and bother should be reported separately in addition to calculation of summary scores. The documented differences, not at least regarding PROs, may in part explain the large variation of post-treatment side effects evident in the medical literature.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, pre-treatment variables, between-country variables, curative treatment

INTRODUCTION

Standard curative treatment of prostate cancer (PCa) patients comprises radical prostatectomy (RP) and high-dose radiotherapy (RAD) with or without adjuvant androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). After adjustment for risk group allocation prostate cancer specific survival appears to be similar after both treatment modalities. [1–3]. However, the patterns of “typical adverse effects (AEs)” (dysfunction within the urinary, sexual, bowel and hormonal domains and related problems) differ substantially. [4,5]. Further, even though comparisons are restricted either to RP or RAD, large and generally unexplained variations of the frequency and severity of typical AEs are reported across studies and countries [6–10]. Such differences in post-treatment patient-related outcomes (PROs) may impact on the individual patient’s choice of RP versus RAD.

Except for different treatment techniques, variations of post-treatment AEs may be related to differences in pre-treatment medical factors (tumor risk group allocation, co-morbidity, general health condition) and socio-demographic factors (age, educational level, civil status). Some groups have documented some impact of pre-treatment PROs on AEs after PR or RAD [11, 12]. However, the knowledge on between-country differences of PROs within urinary and sexual domain is limited. Only Namiki et al have reported on pre-treatment differences of sexual function and bother in Japanese and American men [13].

Our group has initiated a cohort study with research groups in the United States and Spain aiming to perform between-country comparisons of pre- and post-treatment variables and patient-reported typical AEs among patients treated with curative RP or RAD for PCa. The present paper describes for each country, and separately for RP and RAD, pre-treatment medical, socio-demographic factors as well as PROs within the sexual, urinary, bowel and hormonal domain. We also evaluate the correlation between patient-reported dysfunctions and related problems. Finally, for each country we assess the associations between the above mentioned pre-treatment factors and RP or RAD. We anticipate considerable between-country differences in the distribution of pre-treatment variables and the strength of their associations with the selected treatment. We also expect between-country differences when comparing patient-reported pre-treatment dysfunctions and problems within the sexual and urinary domain.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study design and study sites

This study represents a collaboration between Oslo University Hospital, Norway, the PROSTAQA Study Group in Boston, USA, and The Spanish Group of Localized Prostate Cancer, Barcelona, Spain. Each group has published results regarding PROs before and after RP and RAD. [14–18]. However, as the present study only includes patients with clinically categorized T1 or T2 tumors 28 RP and 80 RAD patients with T3/T4 tumors were excluded from the original Norwegian sample In the Spanish sample 10 RP and 65 RAD patients were excluded due to hormonal treatment prior to inclusion.

Patient sampling

Eligible patients for the present study fulfilled the following criteria:

Histologically confirmed PCa

Clinical stage T1 or T2 tumor

Known pre-treatment level of PSA and Gleason score

Planned RP or RAD

No ADT prior to completion of the pre-treatment questionnaire

Treatment techniques

RP was performed by retropubic, laparoscopic or robot-assisted techniques with or without nerve-sparing procedures. RAD (≥ 65 Gy) was delivered as intensity modulated-radiotherapy, 3D- conformal technique or a combination of high-dose rate brachytherapy and external beam radiotherapy. Patients receiving low dose rate brachytherapy as mono-therapy were excluded because this option was not available in Norway [19].

Clinical variables

Risk groups

Three risk groups were defined [20]. Low-risk: cT1-T2a and Gleason score 6 and PSA <10ng/mL. Intermediate- risk: cT2b–T2c or Gleason score 7 or PSA 10–20ng/mL. High- risk; Gleason score 8–10 and/or PSA >20ng/mL.

Other pre-treatment variables assessed by patients’ reports

The Level of education separated “less than high school from “high school or more”. “Single” versus “paired relation” described the relationship status. Co-morbidity was defined as the presence of at least one of five adverse health conditions: 1: diabetes, 2: heart failure and/or myocardial infarction and/or angina, 3; stroke 4; ulcus and/or Irritable Bowel Disease 5; asthma and/or bronchitis and/or breathing problems.

Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC)

Before treatment the patients completed a questionnaire containing a version of the EPIC instrument. EPIC assesses patient-reported sexual, urinary and bowel dysfunctions and problems (“bother”) [21] as well as hormone treatment related AEs [21,22]. The original questionnaire includes 50 items (EPIC-50) but was later abbreviated to 26 items (EPIC-26) [22]. All questions in EPIC-26, completed by the American patients, are included in EPIC-50, used by the Norwegian and Spanish men. The present report is based upon responses to items of EPIC-26.

By 4- or 5- point Likert scales the patient scores his function and related problems within each of the four above domains. The individual scores are then transformed into scales ranging from 0 to 100, with 0 representing maximum dysfunction/maximum problem and 100 indicating no dysfunction/no problem [23]. The scores within each domain are finally averaged. The resulting summary scores reflect both functional aspects and problem experience within the sexual, urinary irritation/obstruction, urinary incontinence, bowel or hormonal domain. Our patients’ answers to each of the 26 EPIC items were also dichotomized according to Sanda et al [16], enabling separation patients with no/very small/small dysfunctions/problems (“absent dysfunction/problems”) from those with moderate / big dysfunctions /problems (“present dysfunction/problems”). In addition, we calculated mean scores for items which content address dysfunction as opposed to problem experience.

Data management and statistics

After approval by the local ethical committees, a combined project data file was established, which for each patient contained medical and socio-demographic data (treatment type, risk group, age, education) and EPIC-assessed PROs. The current study covers only pre-treatment variables.

Using PASW for PC, version 18.0 and separately for the RP and RAD group, variables were described with means and standard deviations or as proportions. Between-country differences were analyzed using one-way ANOVA for continuous variables. Crude associations between pairs of categorical variables were assessed with chi-square tests.

Separately for each country associations between type of treatment (RAD or RP, RP given as a reference) were assessed with univariate and multiple logistic regressions. The strength of associations was expressed by odds ratios (ORs) by 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). P-values <0.01 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 1908 patients (1353 planned for RP; 555 planned for RAD) were eligible for the current study based on their pre-treatment status. There were 753 men from Norway (RP: 627; RAD: 126), 896 from USA (RP: 603: RAD: 293) and 249 from Spain (RP: 123; RAD: 126). More than 95 % of the patients from Norway and Spain were Caucasian whereas 9% of the American patients were black.

Socio-demographics and medical variables

RP patients

In the RP group, significantly more American patients were aged less than 65 years (76%) than those from Norwey (61%) or Spain (52%) (Table 1). Further, among the US patients we also observed the highest prevalence of men without co-morbidities and the highest proportion of patients with at least high school education. More than half of the American operated men had low-risk tumors compared to 31% and 42 % of the Norwegian and Spanish men, respectively. In the Norwegian RP group significantly more patients had high-risk disease (13%) compared to the US (6%) and Spanish (3%) samples.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and disease characteristics of the patients at pre-treatment.

| Radical prostatectomy | Radiotherapy | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Variable, n (%) | Norway | USA | Spain | p-value | Total | Norway | USA | Spain | p-value | Total |

| (n=627) | (n=603) | (n=123) | (n=1353) | (n=126) | (n=293) | (n=126) | (n=555) | |||

| Age, median (range) | 64 (44–78) | 60 (39–80) | 65 (45–75) | <0.00113 | 62 (39–80) | 67 (51–78) | 69 (46–85) | 70 (55–83) | ≤0.00812 | 69 (46–85) |

| <65yrs | 382 (61) | 460 (76) | 64 (52) | <0.00113 | 906 (67) | 41 (33) | 86 (29) | 25 (19) | 0.0092 | 152 (27) |

| No comorbid condition | 450 (72) | 513 (85) | 77 (63) | <0.00113 | 1040 (77) | 64 (51) | 200 (67) | 77 (57) | <0.0011 | 341 (62) |

| Paired relationship | 584 (93) | 523 (87) | 109 (87) | <0.0011 | 1216 (90) | 102 (83) | 227 (78) | 118 (87) | 0.0183 | 447 (81) |

| Education above high school level, | 322 (52) | 511 (85) | 8 (7) | <0.001123 | 841 (62) | 57 (46) | 211 (72) | 16 (12) | <0.001123 | 284 (52) |

| PSA (ng/ml), | ||||||||||

| Median (Range) | 8.2 (1.6–75) | 5.5 (0.5–72) | 7.4 (4–23) | ≤0.002123 | 6.9 (0.5–75) | 9.8 (3–87) | 6.3 (0.5–99) | 7.6 (1.2–38) | ≤0.009123 | 7.6 (0.5–99) |

| PSA group | <0.0011 | <0.00112 | ||||||||

| ≤10.0 | 434 (69) | 525 (87) | 99 (81) | 1058 (78) | 66 (52) | 226 (77) | 114 (84) | 406 (73) | ||

| >10–20 | 162 (26) | 65 (11) | 45 (15) | 250 (18) | 38 (30) | 45 (15) | 15 (11) | 98 (18) | ||

| >20 | 31 (5) | 13 (2) | 1 (1) | 45 (3) | 22 (18) | 22 (8) | 7 (5) | 51 (9) | ||

| cT category | <0.0011 | 0.00512 | ||||||||

| T1 | 393 (63) | 437 (73) | 82 (67) | 912 (67) | 53 (42) | 203 (69) | 82 (67) | 353 (60) | ||

| T2a | 142 (23) | 130 (22) | 33 (27) | 305 (23) | 39.0 (31) | 56 (19) | 33 (27) | 133 (24) | ||

| T2b | 53 (9) | 23 (4) | 8 (7) | 84 (6) | 15 (12) | 24 (8) | 8 (7) | 56 (10) | ||

| T2c | 39 (6) | 13 (2) | 0 (0) | 52 (4) | 18 (14) | 10 (3) | 0 (0) | 32 (6) | ||

| Gleason score | 0.0112 | <0.00123 | ||||||||

| ≤6 | 290 (46) | 370 (61) | 71 (58) | 731 (54) | 42 (34) | 130 (44) | 99 (73) | 271 (50) | ||

| 7 | 280 (45) | 207 (34) | 48 (39) | 535 (40) | 61 (49) | 122 (42) | 32 (24) | 215 (39) | ||

| ≥8 | 57 (9) | 26 (4) | 3 (3) | 86 (6) | 22 (18) | 42 (14) | 3 (8) | 67 (12) | ||

| Risk group | 0.01123 | <0.00112 | ||||||||

| Low | 191 (31) | 322 (53) | 51 (42) | 564 (42) | 26 (21) | 100 (34) | 73 (54) | 199 (36) | ||

| Intermediate | 354 (57) | 246 (41) | 68 (55) | 668 (49) | 65 (52) | 139 (47) | 52 (38) | 256 (46) | ||

| High | 82 (13) | 35 (6) | 4 (3) | 121 (9) | 35 (28) | 54 (18) | 11 (8) | 100 (18) | ||

Norway vs USA

Norway vs Spain

USA vs Spain

RAD patients

Within the RAD group, more Norwegian patients were less than 65 years old than observed among the Spanish patients (Table 1). Among the American patients 72 % had completed high school, the comparable proportions being 46% and 12% in the Norwegian and Spanish group, respectively. More than half of the Spanish patients in the RAD group (54%) had low- risk tumors compared to 21% in the Norwegian and 34% in the US group. The highest proportion of patients with high-risk tumors was observed in the Norwegian sample (28%).

Responses to the EPIC-26

Urinary domain

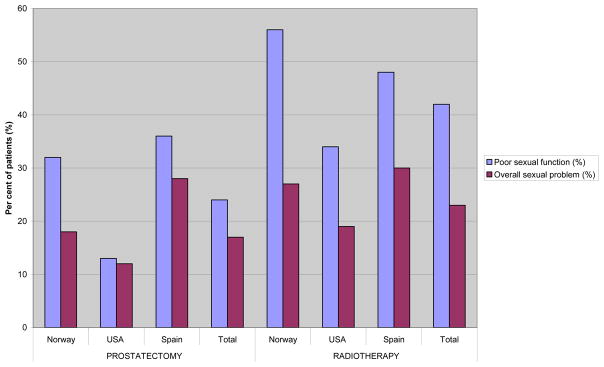

Independent of country and treatment type mean pre-treatment scores were generally high within the urinary domain, the mean urinary incontinence score being >90 for all groups, corresponding to >98% of the patients not using pads (Table 2 and 3). Thus summary scores principally reflected the irritative/obstructive urinary dysfunction/ bother, with significant between-country differences. Further, only about half of Norwegian and US patients in respectively the RP and RAD group who reported moderate or big dysfunction within the urinary domain also reported problems (Figure 1). Among the Spanish patients the proportion of men with obstructive/irritative symptoms and those reporting related problems were more similar.

TABLE 2.

Mean EPIC sum scores for the four domains for each treatment group in Norway, USA and Spain and total at pre-treatment.

| Radical prostatectomy | Radiotherapy | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Variable, mean score (SD) | Norway | USA | Spain | p-value | Total | Norway | USA | Spain | p-value | Total |

| Urinary | ||||||||||

| Incontinence score (1,2,3, 4a)* | 94 (12) | 94 (13) | 94 (15) | 0.99 | 94 (13) | 93 (11) | 92 (14) | 96 (11) | 0.0133 | 93 (13) |

| Irritative/obstructive score (4b,c,d,e)* | 83 (15) | 87 (15) | 94 (12) | <0.001123 | 86 (15) | 83 (15) | 87 (14) | 96 (10) | <0.00123 | 88 (14) |

| Overall problem (5)* | 75 (28) | 80 (27) | 87 (28) | 0.01323 | 78 (28) | 75 (26) | 78 (26) | 93 (21) | <0.00123 | 81 (26) |

| Sexual | ||||||||||

| Sexual score (8a,b,9,10,11,12)* | 67 (25) | 78 (23) | 62 (25) | <0.00113 | 72 (25) | 50 (27) | 59 (29) | 57 (27) | 0.011 | 57 (28) |

| Bowel | ||||||||||

| Bowel score (6a–e,7)* | 95 (9) | 97 (8) | 99 (3) | 0.002123 | 96 (8) | 94 (10) | 95 (10) | 99 (6) | <0.00123 | 96 (9) |

| Hormonal | ||||||||||

| Hormonal score (13a–e)* | 91 (11) | 92 (11) | 96 (10) | <0.00123 | 92 (11) | 88 (13) | 92 (12) | 96 (11) | 0.00123 | 92 (12) |

Norway vs USA

Norway vs Spain

USA vs Spain

EPIC questions used to calculate the mean score.

TABLE 3.

Percent of patients reporting specific levels of distress or dysfunction for each question in EPIC 26.¶

| Radical prostatectomy | Radiotherapy | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Variable | Norway | USA | Spain | p-value | Total | Norway | USA | Spain | p-value | Total |

|

| ||||||||||

| N=627 % | N=603 % | N=123 % | N=1353 % | N=126 % | N=293 % | N=126 % | N=555 % | |||

| Urinary domain | ||||||||||

| Incontinence | ||||||||||

| Leaking >1time per day (1)° | 3 | 4 | 6 | 0.25 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 0.04 | 4 |

| Frequent dribbling (2)° | <1 | 2 | 3 | 0.06 | 2 | <1 | 2 | <1 | 0.32 | 2 |

| Any pad use (3)° | 2 | 1 | <1 | 0.66 | 1 | 0 | <1 | <1 | 0.64 | <1 |

| Leaking problem* (4a)° | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0.23 | 2 | <1 | 2 | 4 | 0.22 | 2 |

| Irritation or obstruction* | ||||||||||

| Dysuria (4b)° | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.28 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0.61 | 1 |

| Hematuria (4c)° | 0 | <1 | <1 | 0.18 | <1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.26 | <1 |

| Weak stream (4d)° | 16 | 12 | 7 | 0.0062 | 13 | 15 | 13 | 5 | ≤0.00523 | 12 |

| Frequency (4e)° | 20 | 17 | 11 | 0.012 | 18 | 21 | 15 | 2 | <0.00123 | 14 |

| Overall urinary problem* (5) ° | 13 | 11 | 13 | 0.59 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 6 | 0.21 | 10 |

| Sexual domain | ||||||||||

| Poor erection (8a)° | 24 | 14 | 23 | <0.0011 | 20 | 46 | 37 | 27 | 0.0032 | 37 |

| Difficulty with orgasm (8b)° | 17 | 12 | 15 | 0.071 | 15 | 39 | 32 | 26 | 0.08 | 32 |

| Erection not firm for intercourse† (9)° | 27 | 17 | 43 | <0.001123 | 24 | 57 | 48 | 52 | 0.263 | 49 |

| Erection not reliable‡ (10)° | 27 | 20 | 42 | ≤0.004123 | 25 | 52 | 44 | 45 | 0.10 | 46 |

| Poor sexual function* (11)° | 32 | 13 | 36 | <0.00113 | 24 | 56 | 34 | 48 | ≤0.00613 | 43 |

| Overall sexual problem* (12)° | 18 | 12 | 28 | ≤0.00413 | 17 | 27 | 18 | 28 | 0.013 | 24 |

The percent of survey respondents reporting the indicated level of dysfunction in the three countries in each treatment group and in total in each treatment group

Moderate or big problem

Erection not firm included all answers except ”firm enough for intercourse”,

erection about half of the times or less was categoriszed as ”erection not reliable”

Norway vs USA

Norway vs Spain

USA vs Spain

The number of EPIC question used

Figure 1.

Per cent of patients reporting moderate or big problem with frequency and/or weak stream and overall urinary function

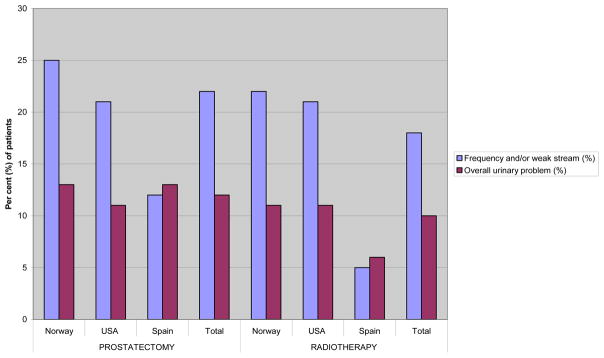

Sexual domain

Both in the RP and the RAD groups the lowest mean scores and the highest percentage of patients with moderate/big dysfunction were observed within the sexual domain, with the highest mean scores among the American patients (Table 2, Table 3 ). Accordingly, the percentages of patients reporting sexual problems were lowest among the US men (RP: 12%, RAD: 18%), and highest among the Spanish men (RP: 28%; RAD: 28%.

In the RAD group about half of the patients reporting sexual dysfunction also experienced sexual problems with similar patterns across the three countries (Figure 2). In the RP group only for the Spanish and the Norwegian patients larger differences were observed between sexually dysfunctioning men and those reporting related problems. Almost all of the relatively few US patients with sexual dysfunction also reported sexual problems.

Figure 2.

Per cent of patients reporting poor or very poor ability to function sexually and % of patients reporting overall moderate or big problems in the sexual domain.

Bowel and Hormonal domains

High summary scores in the bowel and hormonal domains were paralleled by low proportions of men reporting problems in these domains (Table 2). Further analyses of these pre-treatment minimally affected domains were therefore not pursued.

Multivariate analyses

In each of the three countries age ≥65 years was significantly associated with being planned for RAD with considerable numerical differences as to the respective odds ratios (Table 4): Norwegian patients aged ≥65 years were 2.7 times more likely to be planned for RAD than for RP, whereas the comparable likelihood was reflected by an OR of 7 among US men and 4.5 among Spanish patients. Among the American and Norwegian patients, but not among the patients from Spain co-morbidity and presenting with a high-risk tumor were independently associated with RAD. US patients with less than high school education were twice as likely to get RAD compared to those with higher education, with no such association among the Norwegian and Spanish patients. Pre-treatment sexual dysfunction doubled the likelihood to receive RAD for Norwegian and US patients.

TABLE 4.

Uni and multivariate regression analysis, RAD being dependent variable, RP being reference.

| NORWAY | USA | SPAIN | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis |

| OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | |

|

| ||||||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Living together | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Not living together | 2.9 (1.7–5.2) 1 | 2.7 (1.4–5.0) 2 | 1.9 (1.3–2.7) 1 | 2.4 (1.5–3.7) 1 | 1.1 (0.6–2.2) 3 | — |

| Co morbidity | ||||||

| No co morbide condition | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| One or more co morbide condition | 2.5 (1.7–3.7) 1 | 2.1 (1.4–3.2) 1 | 2.6 (1.9–3.7) 1 | 1.7 (1.2–2.6) 2 | 1.4 (0.9–2.3) 3 | — |

| Age | ||||||

| <65yrs | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| ≥65 | 3.2 (2.1–4.9) 1 | 2.7 (1.7–4.1) 1 | 7.7 (5.7–10.6) 1 | 7.0 (5.0–10.0) 1 | 4.5 (2.8–7.4) 1 | 4.8 (2.9–8.2) 1 |

| Education | ||||||

| ≥High school | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| <High school | 1.3 (0.9–1.8) 3 | — | 2.2 (1.5–3.0) 1 | 1.9 (1.2–2.9) 2 | 0.5 (0.2–1.2) 3 | — |

| Risk group | ||||||

| Low | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Intermediate | 1.3 (0.8–2.2) 3 | 1.1 (0.7–2.0) 3 | 1.8 (1.3–2.5) 1 | 1.5 (1.0–2.1) 2 | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) 3 | — |

| High | 3.1 (1.8–5.5) 1 | 2.9 (1.6–5.4) 1 | 5.0 (3.1–8.0) 1 | 3.4 (1.9–6.1) 1 | 4.2 (1.4–12.9) 2 | 6.9 (2.1–22.2) 1 |

| EPIC | ||||||

| Sexual function (11) | ||||||

| Small or less problem | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Moderate or big problem | 2.6 (1.8–3.9) 1 | 1.8 (1.0–2.9) 2 | 3.6 (2.5–5.0) 1 | 1.9 (1.2–2.9) 2 | 2.2 (1.4–3.4) 1 | 2.0 (1.2–3.3) 2 |

| Sexual problem (12) | ||||||

| Small or less problem | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Moderate or big problem | 1.7 (1.0–2.6) 2 | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) 3 | 1.6 (1.1–2.4) 2 | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) 3 | 1.3 (0.8–2.1) 3 | — |

p≤0.001,

p>0.001≤0.05,

p>0.05

DISCUSSION

Confirming our hypothesis significant between-country differences emerged of pre-treatment variables among Norwegian, American and Spanish patients planned for either RP or RAD, the socio-demographic and medical variables differing more in the RP than in the RAD group. American men planned for RP were younger than the European patients. They had less often co-morbidity and more had a high education level. Fewer US patients than patients from the two European countries had an aggressive PCa and fewer of the American men reported sexual dysfunction. Age ≥65years increased the likelihood to receive RAD for patients from all three countries though with considerable between-country variation of the strength of the associations. In general, but with between-country differences the proportion of patients with obstructive/irritative urinary dysfunction or impaired sexual function exceeded the percentage of men who experienced problems related to their dysfunction.

Differences in pre-treatment medical characteristics (tumor risk group, co-morbidity) between patients planned for RP and RAD are well-known from previous studies [4, 24]. However, few studies have in depth dealt with between-country variability of the distribution of these pre-treatment parameters within either the RP or RAD group and of the strength of the association with the final treatment. For each treatment modality (RP or RAD) we observed substantial between-country differences regarding pre-treatment socio-demographics, disease characteristics and dysfunctions within the urinary and sexual domains. Our observations thus add to Namiki et al’s study, which shows that the American patients were younger, healthier and had less disease burden than men from Japan [25]. We also show considerable between-country differences of the associations between the elected treatment modality and the medical an socio-demographic variables. Whether these latter observations reflect different views of the responsible doctors or mirror variability of patients’ preferences can not be decided based on our data. However, the international literature on post-treatment typical AEs has so far only limitedly considered these pre-treatment between-country differences as a possible explanation for the considerable variations in typical AEs after either RP or RAD reported in the medical literature.

Assessment of the patient’s typical post-treatment AEs after curative treatment of PCa usually relies on PROs assessed by questionnaires which often combine dysfunctions and problems as summary scores, which may unjustifiably disregard important differences between dysfunction and bother. In agreement with Gore et al [26] and Reeve et al [27] our data thus indicate that dysfunction should be separated from problem evaluation, in addition to reporting summary scores: Within the urinary domain the proportions of US and Norwegian patients with bother was lower than the percentage of men reporting dysfunction. They were apparently less bothered than indicated by their impaired function. We do not have data to explain why many Norwegian and US patients did not regard their impaired urinary function as a problem. Increased voiding frequency and weak stream may, however, may be considered as normality among men in that age group. On the other hand, the number of men reporting both dysfunction and problem was about equal among the Spanish patients. They also represented the group with least urinary dysfunction (urinary frequency or weak stream). We speculate whether elderly Spanish men, more often than the American or Norwegian ones, view impaired voiding as “normal” and therefore report only the most disturbing experiences. Also in the sexual domain the proportions of patients with dysfunction exceeded those being bothered, except for the US men planned for RP. Many older PCa patients probably accept impaired sexual function as a common consequence of ageing and comorbidity. On the other hand, among the younger and healthier US patients in the RP group impaired sexual function is more often experienced as a bothersome loss.

In the multivariate analyses and similar for the US and Norwegian patients we observed that pre-treatment erectile dysfunction doubled the likelihood to receive RAD. We have no good explanation for this finding and tend to view this observation as a “finding by chance”.

Our findings of the between-country differences of the mean scores of self-reported sexual and erectile function and overall sexual problems within both the RP and RAD groups are new. We speculate whether such between-country differences, at least in part can explain the variability of post-treatment erectile dysfunction as reported in review articles including studies from multiple countries [9]. Several previous analyses have documented that good pre-treatment erectile and urinary function predicts satisfactory post-treatment outcome within these domains, together with young age [11, 12, 28]. Planned analyses of our patients’ post-treatment PROs will deal with these issues.

Strength and limitations

Selection bias can not be overseen in our study: RP was planned in more than half of our patients, in particular in those from American and Norwegian cohort. This observation requires an explanation: For patients with T1 or T2 tumors the most common treatment in America and in Norway is RP, especially in the younger ones[29,30]. However, this tendency was not observed in the Spanish cohort. Most probably the country-related differences in our study as to RP vs RAD mirror different treatment strategies as well as different patient views. Secondly, well-educated, sexually active American men may have selected recognized institutions for their treatment, whereas the Spanish and Norwegian men probably had this opportunity to a lesser degree and were probably more likely to represent the average patient with localized prostate cancer diagnosed in the respective country. Thirdly, our study covers the last decade, when also other treatment modalities were available such as low dose grade radiotherapy or active surveillance. For our patients we lack detailed information on all selection criteria for the choice of RP or RAD. Neither do we know to what degree the final treatment election was based on patient’s or doctor’s preferences, or whether the patients have been informed about the different treatment options and their AEs. In this mainly descriptive study we have therefore refrained from discussing the analyzed variables as selection criteria. Sufficient information on the pre-treatment use of erectile aids, important for evaluation of erectile function, was not available. Finally, the limited number of non-Caucasians prevented us to analyze our data stratified for race.

The main strengths of our study are the large sample size and the use of the same questions to evaluate function and problems within the domains expected to be affected by curative treatment of PCa. The fact all patients were hormone-naïve prior to questionnaire completion. is regarded as an advantage.

Conclusion and Clinical Practice Points

In PCa patients from Norway, USA or Spain planned for RP or RAD considerable pre-treatment between-country differences were confirmed regarding age and risk group. Our results as to considerable between differences of dysfunction and bother within the sexual and urinary domain are new. As the above pre-treatment factors may be related to post-treatment outcomes, they should not be overseen when discussing published differences of post-treatment outcomes across countries. The finding of considerable discrepancies between dysfunction and problem experience within the urinary and sexual domain is also a new observation and should be taken into account in pre-treatment counseling a patient with PCa before final choice of treatment modality.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Kibel AS, Ciezki JP, Klein EA, Reddy CA, Lubahn JD, Haslag-Minoff J, et al. Survival Among Men With Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer Treated With Radical Prostatectomy or Radiation Therapy in the Prostate Specific Antigen Era. J Urol. 2012;187:1259–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.11.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendenhall WM, Nichols RC, Henderson R, Mendenhall NP. Is radical prostatectomy the “gold standard” for localized prostate cancer? Am J Clin Oncol. 2010;33:511–515. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181b4af05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilt TJ, MacDonald R, Rutks I, Shamliyan TA, Taylor BC, Kane RL. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness and harms of treatments for clinically localized prostate cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:435–448. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-6-200803180-00209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Resnick MJ, Koyama T, Fan KH, Albertsen PC, Goodman M, Hamilton AS, et al. Long-Term Functional Outcomes after Treatment for Localized Prostate Cancer. New Engl J Med. 2013;368:436–445. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Potosky AL, Davis WW, Hoffman RM, Stanford JL, Stephenson RA, Penson DF, et al. Five-year outcomes after prostatectomy or radiotherapy for prostate cancer: The prostate cancer outcomes study. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1358–1367. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Namiki S, Kwan L, Kagawa-Singer M, Terai A, Arai Y, Litwin MS. Urinary quality of life after prostatectomy or radiation for localized prostate cancer: a prospective longitudinal cross-cultural study between Japanese and U.S. men. Urology. 2008;71:1103–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hugosson J, Stranne J, Carlsson SV. Radical retropubic prostatectomy: a review of outcomes and side-effects. Acta Oncol. 2011;50(Suppl 1):92–97. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.535848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alivizatos G, Skolarikos A. Incontinence and erectile dysfunction following radical prostatectomy: a review. Scient World J. 2005;5:747–758. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2005.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tal R, Alphs HH, Krebs P, Nelson CJ, Mulhall JP. Erectile function recovery rate after radical prostatectomy: a meta-analysis. J Sex Med. 2009;6:2538–2546. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01351.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burnett AL, Aus G, Canby-Hagino ED, Cookson MS, D’Amico AV, Dmochowski RR, et al. Erectile function outcome reporting after clinically localized prostate cancer treatment. J Urol. 2007;178:597–601. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinkawa M, Gagel B, Piroth MD, Fischedick K, Asadpour B, Kehl M, et al. Erectile dysfunction after external beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2009;55:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wille S, Heidenreich A, Hofmann R, Engelmann U. Preoperative erectile function is one predictor for post prostatectomy incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2007;26:140–143. doi: 10.1002/nau.20314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Namiki S, Kwan L, Kagawa-Singer M, Saito S, Terai A, Satoh T, et al. Sexual function reported by Japanese and American men. J Urol. 2008;179:245–249. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrer M, Suarez JF, Guedea F, Fernandez P, Macias V, Marino A, et al. Health-related quality of life 2 years after treatment with radical prostatectomy, prostate brachytherapy, or external beam radiotherapy in patients with clinically localized prostate cancer. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:421–432. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pardo Y, Guedea F, Aguilo F, Fernandez P, Macias V, Marino A, et al. Quality-of-Life Impact of Primary Treatments for Localized Prostate Cancer in Patients Without Hormonal Treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4687–4696. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, Sandler HM, Northouse L, Hembroff L, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. New Engl J Med. 2008;358:1250–1261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steinsvik EA, Axcrona K, Angelsen A, Beisland C, Dahl A, Eri LM, et al. Does a surgeon’s annual radical prostatectomy volume predict the risk of positive surgical margins and urinary incontinence at one-year follow-up? - Findings from a prospective national study. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2012 doi: 10.3109/00365599.2012.707684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinsvik EA, Axcrona K, Dahl AA, Eri LM, Stensvold A, Fossa SD. Can sexual bother after radical prostatectomy be predicted preoperatively? Findings from a prospective national study of the relation between sexual function, activity and bother. Br J Int. 2012;109:1366–1374. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lilleby W, Tafjord G, Raabe NK. Implementation of High-Dose-Rate Brachytherapy and Androgen Deprivation in Patients With Prostate Cancer. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:933–939. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, Sandler HM, Sanda MG. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2000;56:899–905. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00858-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szymanski KM, Wei JT, Dunn RL, Sanda MG. Development and Validation of an Abbreviated Version of the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite Instrument for Measuring Health-related Quality of Life Among Prostate Cancer Survivors. Urology. 2010;76:1245–1250. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanda MG, Wei JT, Litwin MS. Scoring Instructions for the Expanded Prostate cancer Index Composite Short Form (EPIC-26) 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang GJ, Sadetsky N, Penson DF. Health Related Quality of Life for Men Treated for Localized Prostate Cancer With Long-Term Followup. J Urol. 2010;183:2206–2212. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Namiki S, Kwan L, Kagawa-Singer M, Tochigi T, Ioritani N, Terai A, et al. Sexual function following radical prostatectomy: a prospective longitudinal study of cultural differences between Japanese and American men. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2008;11:298–302. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4501013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gore JL, Gollapudi K, Bergman J, Kwan L, Krupski TL, Litwin MS. Correlates of Bother Following Treatment for Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer. J Urol. 2010;184:1309–1314. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reeve BB, Potosky AL, Willis GB. Should function and bother be measured and reported separately for prostate cancer quality-of-life domains? Urology. 2006;68:599–603. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alemozaffar M, Regan MM, Cooperberg MR, Wei JT, Michalski JM, Sandler HM, et al. Prediction of erectile function following treatment for prostate cancer. JAMA. 2011;306:1205–1214. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]