Abstract

Background:

A large proportion of the patients with papillary thyroid microcarcinoma are young women. Therefore, minimally invasive endoscopic thyroidectomy with central neck dissection (CND) emerged and showed well-accepted results with improved cosmetic outcome, accelerated healing, and comforting the patients. This study aimed to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of robotic total thyroidectomy with CND via bilateral axillo-breast approach (BABA), compared with conventional open procedure in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma.

Methods:

One-hundred patients with papillary thyroid microcarcinoma from March 2014 to January 2015 in Jinan Military General Hospital of People's Liberation Army (PLA) were randomly assigned to robotic group or conventional open approach group (n = 50 in each group). The total operative time, estimated intraoperative blood loss, numbers of lymph node removed, visual analog scale (VAS), postoperative hospital stay time, complications, and numerical scoring system (NSS, used to assess cosmetic effect) were analyzed.

Results:

The robotic total thyroidectomy with CND via BABA was successfully performed in robotic group. There were no conversion from the robotic surgeries to open or endoscopic surgery. The subclinical central lymph node metastasis rate was 35%. The mean operative time of the robotic group was longer than that of the conventional open approach group (118.8 ± 16.5 min vs. 90.7 ± 10.3 min, P < 0.05). The study showed significant differences between the two groups in terms of the VASs (2.1 ± 1.0 vs. 3.8 ± 1.2, P < 0.05) and NSS (8.9 ± 0.8 vs. 4.8 ± 1.7, P < 0.05). The differences between the two groups in the estimated intraoperative blood loss, postoperative hospital stay time, numbers of lymph node removed, postoperative thyroglobulin levels, and complications were not statistically significant (all P > 0.05). Neither iatrogenic implantation nor metastasis occurred in punctured porous channel or chest wall in both groups. Postoperative cosmetic results were very satisfactory in the robotic group.

Conclusions:

Robotic total thyroidectomy with CND via BABA is safe and effective for Chinese patients with papillary thyroid microcarcinoma who worry about the neck scars.

Keywords: Bilateral Axillo-breast Approach, da Vinci Si Surgical System, Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma, Robotic Central Lymph Node Dissection, Robotic Total Thyroidectomy

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma is increasing in recent years, and a large proportion of these patients are young women. Therefore, minimally invasive endoscopic thyroidectomy with central neck dissection (CND) emerged and showed well-accepted results with improved cosmetic outcome, accelerated healing, and comforting the patients. Robotic thyroidectomy via a transaxillary approach was first described by Kang et al.[1] in 2009. Thereafter, various operative approaches, including axillary-breast-anterior chest approach, transoral periosteal approach, and retroauricular approach, were introduced by many surgeons.[2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11] The aim of this prospective randomized study was to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of robotic total thyroidectomy with CND via bilateral axillo-breast approach (BABA), compared to the conventional low-collar incision method for the treatment of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma.

METHODS

Patient eligibility and study design

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Jinan Military General Hospital of People's Liberation Army (PLA). The prospective randomized clinical study involved 100 patients with papillary thyroid microcarcinoma (17 males and 83 females), with an average age of 41.2 years (range: 21–63 years), from March 2014 to January 2015, in Jinan Military General Hospital of PLA. Before grouping, we described the operative methods and relative complications between robotic thyroidectomy and open thyroidectomy to the patients. All patients provided written informed consent for this prospective randomized study. Then, the patients were randomly given a number and assigned to the corresponding group: 50 patients received robotic total thyroidectomy with CND via BABA (using da Vinci Si Surgical System, Intuitive Surgical Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA), and 50 were operated with conventional low-collar incision approach.

The inclusion criteria for this prospective randomized study were as follows: (1) intrathyroidal papillary carcinoma smaller than 10 mm in diameter; and (2) no evidence of central or lateral lymph node metastasis. All patients were evaluated preoperatively via sonography, fine-needle aspiration cytology, thyroid function, and/or computed tomography (CT). The exclusion criteria included a history of thyroiditis, Graves’ disease, previous neck or thyroid surgeries, irradiation history, obesity (body mass index >30 kg/m2), enlarged thyroid gland detected by ultrasound examination (one thyroid lobe volume >40 ml), and a possible extrathyroidal extension or abutment on the thyroid capsule, especially when occurrence was near the tracheoesophageal groove detected by preoperative sonography or CT. We evaluated the vocal cord mobility with laryngoscope before the surgery.

All procedures were performed by one surgeon (Dr. Qing-Qing He). We analyzed the medical records and evaluated surgical outcomes including the total operative time, estimated intraoperative blood loss, numbers of lymph node removed, visual analog scale (VAS), postoperative hospital stay time, complications, and numerical scoring system (NSS) in all patients. The cosmetic results were recorded using a scoring system ranging from 1 to 4 levels (1: extremely, 2: fairly, 3: normal, and 4: not at all), and NSS was used for patients’ self-assessment in the outpatient clinic at 1 month and 3 months after the operation to grade the cosmetic outcome between 0 and 10. All patients were followed up in outpatient clinic at 1, 3, and 6 months, and then every 6 months to detect thyroid function and thyroglobulin (Tg) level.

Surgical technique

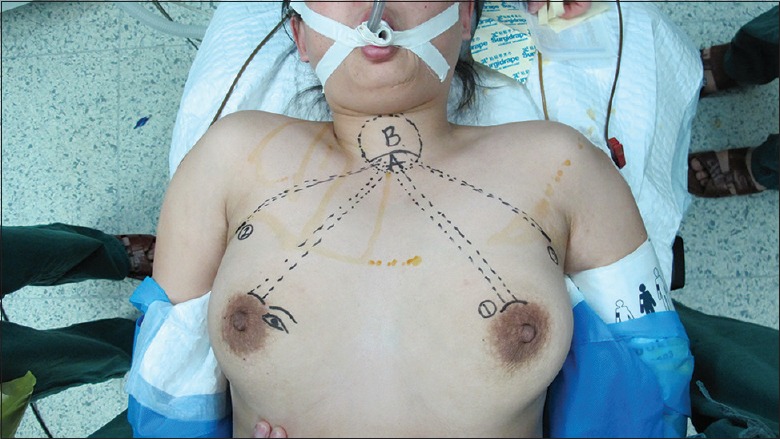

Robotic total thyroidectomy

Under general endotracheal anesthesia, patients were placed on the operating table in the supine position with the neck extended slightly and both arms slightly abducted to allow insertion of the axillary port. After draping, we draw the instrument arm trajectory lines and working area on patient's chest and neck for reference [Figure 1]. Using a 23-gauge spinal needle, we injected diluted epinephrine solutions (1:200,000, 100 ml) and ropivacaine hydrochloride (100 mg) into the subcutaneous areas of both breasts and axilla, as well as the subplatysmal layer of the neck for easy dissection and less bleeding.

Figure 1.

Drawing instrument arm trajectory lines and working area.

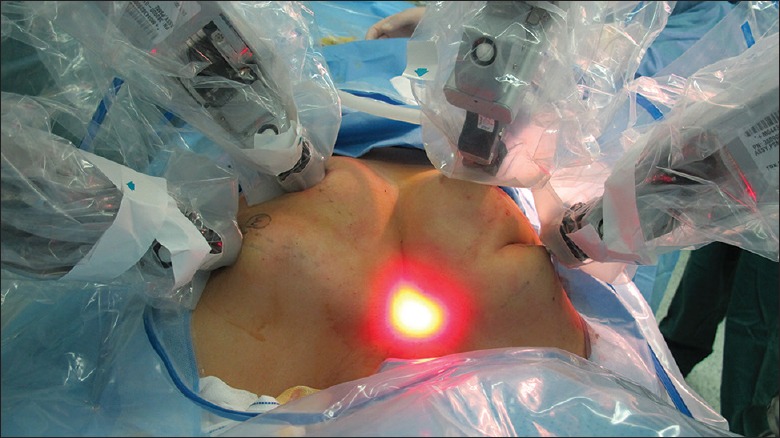

BABA included 5 mm or 8 mm axillary crease incisions and two circumareolar incisions about 8 mm on the left side and 12 mm on the right side, respectively. The 12-mm circumareolar incision was used as a camera port and can be moved to the left breast if the surgeon prefers. Blunt dissection was carefully performed with a vascular tunneler from the incision superiorly to the suprasternal fossa [Figure 1, area A] in trajectory lines and laterally to the medial border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Once the working space was found, the robotic column was placed parallel to the camera port and trocars were inserted into tunnels. Carbon dioxide gas was then insufflated up to 6–7 mmHg (1mmHg=0.133 kPa). Next came to the placement of instrument arms. Place the camera port first (E port) using a disposable 12 mm trocar. Place the instrument arm 1 port on the circumareolar trocar. Place the instrument arm 2 or 3 port in the trocars of the axilla followed by docking the robot cart [Figure 2]. Camera port should be 15 cm away from the thyroid. Following above procedures, the 30° endoscope was placed in the circumareolar area on the side of the lesion through a 12 mm trocar. Then, the Harmonic scalpel was placed on the circumareolar area on the contralateral side through an 8 mm trocar. Furthermore, a 5 mm Maryland dissector was placed in the axillary area (same side as the lesion) and 5 mm ProGrasp Forceps (Intuitive Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) were placed in the axillary area on the contralateral side, as shown in Figure 2. The harmonic scalpel was used for sharp dissection to enlarge the subplatysmal space. The working space was extended superiorly, laterally, and inferiorly to the level of the thyroid cartilage, the medial border of each sternocleidomastoid muscle, and the anterior chest, respectively [Figure 1, areas A and B].

Figure 2.

Each of the four trocars was docked with a robotic arm.

After the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the strap muscle were identified, we cut through the linea alba cervicalis incision with a harmonic scalpel between the strap muscles from the suprasternal notch to thyroid cartilage. The general principle of surgical procedures for robotic total thyroidectomy was the same as conventional open thyroidectomy.

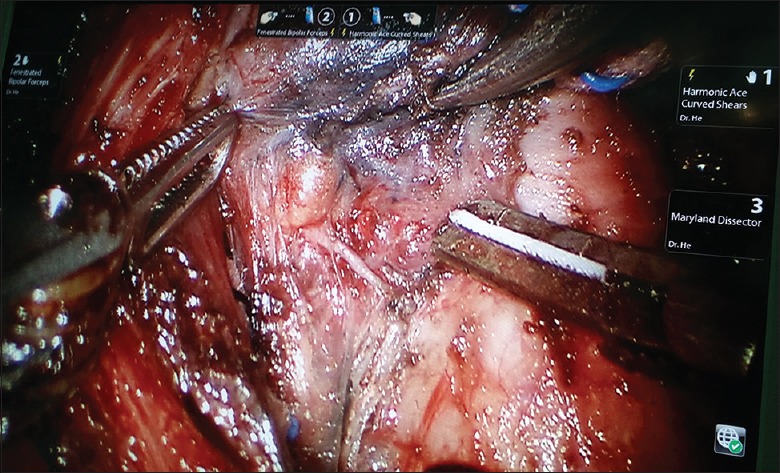

We should identify the tracheal wall, expose it as a midline landmark, and dissect the lower pole of thyroid from the adipose tissue or trachea. During this procedure, we should avoid injuries to the tracheal wall. With delicate blunt dissection, both thyroid lobes were exposed and examined for pathological changes, and with a strictly median orientation, the primary isthmus was removed using the harmonic scalpel. The upper pole of the thyroid was drawn downward, and superior thyroid vessels were identified and individually divided close to the thyroid capsule to avoid injuring the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve. During dissection, the superior parathyroid gland should be identified and left intact in situ [Figures 3 and 4].

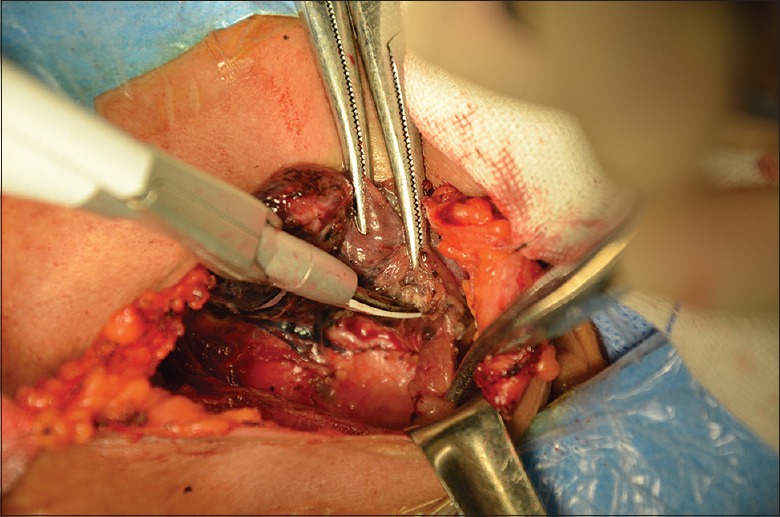

Figure 3.

Identifying and protecting parathyroid glands and the recurrent laryngeal nerve.

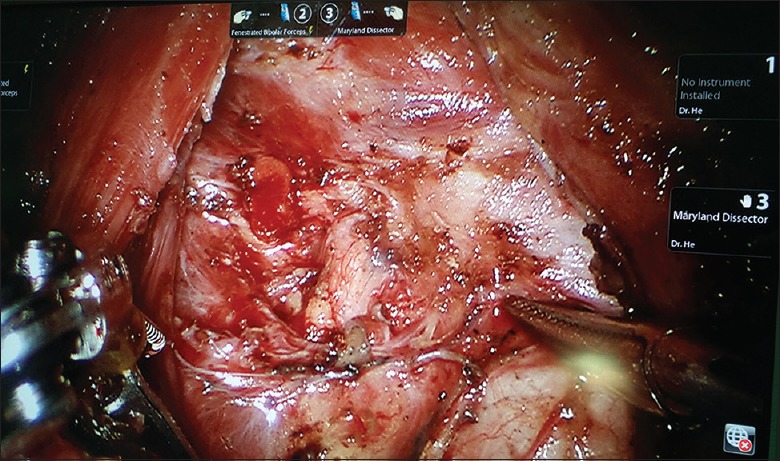

Figure 4.

Robotic total thyroidectomy with central neck dissection showing the course of the ipsilateral (right) recurrent laryngeal nerve and the superior parathyroid gland.

The thyroid was retracted medially, and the middle thyroid vein was identified and coagulated off carefully. Careful dissection was performed to avoid the inferior thyroid artery and the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN). We can easily identify and preserve the RLNs under magnified 10–15 times surgical view [Figures 3 and 4]. The inferior parathyroid gland was identified and left intact in situ as well. After the inferior thyroid vein and thyrothymic ligament had been recognized, the thyroid was retracted upward and medially. Finally, proper application of the harmonic scalpel can successfully remove the thyroid gland from the trachea. Circular resection is recognized as a safe and highly effective method in robotic thyroidectomy via BABA for bilateral thyroid lesions. We did not perform a clip closure. Particular attention should be paid to ensure sufficient distance of the heated harmonic scalpel from the RLN and the visible parathyroids. We dissected the level 4 lymph nodes (delphian/prelaryngeal, pretracheal, and paratracheal lymph nodes) using the robotic system. During ipsilateral or bilateral CND, the lymph nodes of the central compartment were carefully dissected to avoid injuries to the RLN and parathyroids. Application of carbon nanoparticles suspensions injection can stain the lymph nodes of the center compartment while leaving the parathyroid glands unstained (because of the negative development of parathyroid glands to carbon nanoparticles, Chongqing Lummy Pharmaceuticals, China), thus helping to identify and protect parathyroid glands and the RLN [Figures 3 and 4], as well as facilitating the identification and clearance of lymph nodes. We made every effort to perform an en bloc resection. The resected specimen was extracted through enlarging the axillary skin incision by a specimen pouch. The surgical area was douched by 500 ml sterile distilled water (42°C). Vacuum-assisted draining system should be placed in the operative area though the axilla tunnel. The wounds were closed with 5-0 absorbable monofilament sutures using an atraumatic needle, followed by placement of Steri-Strips.

Conventional open approach

Patients in the conventional open approach group underwent conventional open total thyroidectomy with central lymph node dissection in the supine position with neck extension under general endotracheal anesthesia. A 5 cm low-collar incision was made above the sternal notch. The lower layer of the platysma was cut through, and subplatysmal flap dissection was performed from the sternal notch to the level of the thyroid cartilage superiorly. The linea alba cervicalis of the strap muscles was divided vertically, and the thyroid gland was exposed. Dissection of the thyroid and central lymph nodes was performed with harmonic Focus (Ethicon Endo-Surgery Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA).[12] In 50 cases, every effort was made to identify and preserve all parathyroid glands and the RLNs with the negative development of parathyroid glands by carbon nanoparticles [Figure 5]. No knotting tie was left in the surgical areas. Parathyroid glands were transplanted in the sternocleidomastoid muscle once we found that the blood supply to the glands was compromised. Then, the surgical field was douched by 500 ml sterile distilled water (42°C). The drain was placed in the surgical area though the incision. The wounds were closed by an atraumatic needle with 5-0 absorbable sutures.

Figure 5.

Identifying and exposing recurrent laryngeal nerve, the negative development of parathyroid glands by Carbon Nanoparticles.

Postoperative care

There was no difference between the two groups as for the postoperative care. Patients with no complications were usually discharged on day 3 to day 5 after the surgery. All the patients received thyroid hormone replacement therapy for life-long time. All complications were recorded.

Statistical analysis

For descriptive statistics of quantitative variables, mean ± standard deviation (SD) and range were used to describe central tendency and dispersion. For analysis of the differences in proportions, Chi-square test was used. Fisher's exact test was used if the assumptions of Chi-square test were violated. Independent samples t-test was used to compare the level of quantitative variables between the two groups. Data were analyzed using SPSS 15.0 on Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The clinicopathologic characteristics of 100 patients with papillary thyroid microcarcinoma are summarized in Table 1. The robotic total thyroidectomy with CND was completed successfully in fifty patients of robotic group. There were no conversion from the robotic surgeries to open or endoscopic surgeries. Permanent pathological diagnosis showed that all 100 patients had papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. In the robotic group, mean time of creating workspace was 16.0 ± 5.3 min, docking stage time was 10.5 ± 3.2 min, and console stage time was 92.0 ± 11.5 min. The mean total operative time of the robotic group was longer than that of conventional open approach group (118.8 ± 16.5 min vs. 90.7 ± 10.3 min, P < 0.05). This study found the statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of the VASs for pain assessment (2.1 ± 1.0 vs. 3.8 ± 1.2, P < 0.05) and NSS (8.9 ± 0.8 vs. 4.8 ± 1.7, P < 0.05). The differences of the two groups in the estimated intraoperative blood loss, postoperative hospital stay time, numbers of lymph node removed, primary tumor sizes, total drain volumes, mean draining days, and number of patients whose tumors showed multicentricity or multifocality were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). The complications in both groups, such as hypoparathyroidism (temporary), RLN paralysis (temporary), seroma, skin burn, flap necrosis, hematoma, wound infection, chyle leakage, and postoperative Tg levels, were not statistically different (all P > 0.05). Among the 100 patients, 35 (35%) had subclinical central lymph node metastasis. The more patients (19 patients) in robotic group had lymph node metastasis (vs. 16 patients in conventional open approach group), but this did not influence the final results in the staging (according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging, 7th edition) of both groups (P > 0.05).

Table 1.

Clinical data and postoperative outcomes between robotic and conventional open approach groups

| Items | Robotic group (n = 50) | Conventional open approach group (n = 50) | Statistical values | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 40.9 ± 9.8 | 41.5 ± 11.7 | 0.278* | >0.05 |

| Male/female, n | 9/41 | 8/42 | 0.071† | >0.05 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.9 ± 3.5 | 23.8 ± 3.1 | 1.664* | >0.05 |

| Primary tumor size (mm) | 5.07 ± 3.3 | 4.96 ± 3.1 | 0.172* | >0.05 |

| Multicentricity/multifocality, n | 7 | 8 | 0.078† | >0.05 |

| Type of surgery, n | ||||

| Total thyroidectomy with CND | 44 | 43 | 0.088† | >0.05 |

| Total thyroidectomy with bilateral CND | 6 | 7 | 0.120† | >0.05 |

| Parathyroid gland autotransplantation, n | 10 | 16 | 1.871† | >0.05 |

| Total number of removed lymph nodes | 6.7 ± 2.0 | 6.8 ± 2.1 | 0.268* | >0.05 |

| Central lymph node metastasis, n | 19 | 16 | 0.396† | >0.05 |

| Operating time (min) | 118.8 ± 16.5 | 90.7 ± 10.3 | 10.215* | <0.05 |

| Estimated blood loss (ml) | <20 | <20 | ||

| Postoperative hospital stay (days) | 5.1 ± 1.4 | 5.3 ± 1.6 | 0.665* | >0.05 |

| VAS scores (24 h) | 2.1 ± 1.0 | 3.8 ± 1.2 | 7.696* | <0.05 |

| NSS scores | 8.9 ± 0.8 | 4.8 ± 1.7 | 15.108* | <0.05 |

| Total drain volume (ml) | 189.9 ± 48.3 | 195.7 ± 50.4 | 0.588* | >0.05 |

| Mean drain days (days) | 4.4 ± 2.4 | 5.1 ± 3.7 | 1.122* | >0.05 |

| Postoperative complications, n | 2.486† | >0.05 | ||

| Postoperative bleeding | 0 | 0 | ||

| Subcutaneous emphysema | 0 | 0 | ||

| Pneumomediastinum | 0 | 0 | ||

| Temporary hypoparathyroidism | 10 | 17 | ||

| RLN paralysis (temporary) | 1 | 0 | ||

| Seroma | 1 | 0 | ||

| Skin burn | 0 | 0 | ||

| Flap necrosis | 0 | 0 | ||

| Hematoma | 0 | 0 | ||

| Wound infection | 0 | 0 | ||

| Chyle leakage | 0 | 0 | ||

| Postoperative Tg level (ng/ml) | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 1.000* | >0.05 |

| Postoperative cosmetic result, n | 92.165† | <0.05 | ||

| Not at all | 0 | 0 | ||

| Normal | 0 | 3 | ||

| Fairly | 1 | 46 | ||

| Extremely | 49 | 1 |

The data were shown as mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise indicated. *t value; †Chi-square value. BMI: Body mass index; CND: Central neck dissection; RLN: Recurrent laryngeal nerve; VAS: Visual analog scale; NSS: Numerical score system; Tg: Thyroglobulin.

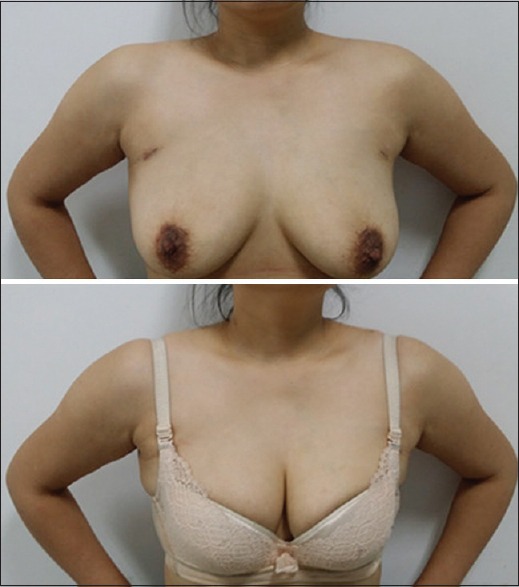

Postoperative cosmetic result was extremely satisfying in robotic group except one patient's suprasternal fossa became shallow with minimal numbness and tingling [Figure 6]. One patient in the robotic group experienced transient vocal cord palsy, but this resolved within 2 months without any treatment. After the hoarseness had disappeared, we observed normal movement of the vocal cords by laryngoscope examination. None of patients had permanent RLN palsy or permanent postoperative hypocalcemia. Neither iatrogenic implantation nor metastasis occurred in punctured porous channel or chest wall was found by inspection or ultrasound during follow-up.

Figure 6.

Scar cosmesis 1 month after robotic total thyroidectomy with central neck dissection, which could be covered by bra.

DISCUSSION

The cervical approach is currently the “gold standard” procedure for thyroidectomy. The conventional surgical approach is to extend the incision into a large transverse incision to complete the required neck dissection. Because the anterior neck is prominent and constantly exposed part of the body, an unsightly neck scars can be distressing for the patients. Furthermore, a majority of patients with papillary thyroid microcarcinoma are young women, who prefer no scar in the neck. Therefore, surgeons have made every effort to resolve the scar problem. In 1997, the first endoscopic thyroidectomy was performed by Hüscher et al.[13] The feasibility of robotic thyroidectomy with the transaxillary approach has been demonstrated by Kang et al.[1] in 2009, which further improved the cosmesis. The obvious advantage of the extracervical approach is the absence of visible scar in the neck or upper chest. According to anatomical access, novel approaches such as postauricular and transoral approaches have been reported.[4,5,6] To the best of our knowledge, some modified approaches have been reported in literature, which could be grouped into small cervical incisions, either the natural body orifice or the surface of the body; the distant approaches such as the chest wall, periareolar, axillary, postauricular, and transoral; and combined approaches. All of the approaches have their own merits and drawbacks, such as the transaxillary approach is limited in arriving at the lymph nodes of the contralateral central compartment.[9,10] However, many reports have described the feasibility of thyroidectomy with robotic system for benign thyroid lesions.[14,15,16]

Concerning the oncological safety, robotic procedures for thyroid cancers are controversial.[17,18,19,20,21] Papillary thyroid microcarcinoma has a very good prognosis. Some studies had reported that total thyroidectomy with prophylactic central lymph node dissection is necessary in patients with papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. For any new emerging technique, careful patient selection is essential.[22] While tailoring the surgical approach to the patients’ concerns and desires is important, adhering to fundamental oncosurgical principles should always be a priority. The oncological safety is more important than the cosmetic demand. In this study, the subclinical central lymph node metastasis rate was 35%, and the rate of multicentricity or multifocality in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma was 15%. This comparative study suggested that there were no significant differences regarding the oncological and the technical safeties between two groups. Robotic procedure uniquely provided a three-dimensional vision, the flexible robotic instruments with seven degree of freedom, and precise simulation-based technology. These enabled surgeons to access deep, narrow spaces for a complete CND and to identify and preserve the RLN and parathyroid glands (parathyroid gland autotransplantation: 10 in robotic group versus 16 in conventional open approach group, P > 0.05). However, robotic procedure is more invasive, more expensive, and more time-consuming than conventional open thyroidectomy.[23,24,25] Other disadvantages for robotic procedure are lack of both tactile sensation and tensile feedback. However, the formation of visual thinking facilitated by robots can make up for the lack of tactile feedback. Robotic surgery could provide surgeons with the best opportunities to transform the thinking mode. In the future, we intend to compare the long-term follow-up results and oncologic safety in a large sample size. According to the results of the study, we are going to broaden our indications.[26]

The BABA permits a full and symmetrical surgical view of important anatomic (structures such as the superior and inferior thyroidal vessels, the RLNs, the parathyroid glands, and the trachea), bilateral thyroid exploration, more workspace for instrument use, and the removal of larger nodules. No brachial plexus injury and axillary skin flap perforations happened in the BABA.[2,3,10] Robotic total thyroidectomy with CND via BABA had similar complication rates as open procedure. In terms of clinical safety and effectiveness, robotic total thyroidectomy with CND was similar to open surgery. The small scars in the bilateral axilla and nipple areola were almost invisible. However, some young women would refuse to receive this surgery since the BABA would involve their breast. Further studies are needed to explore other better approaches to minimize this disadvantage.[4,6,8,27,28,29,30,31]

In conclusion, robotic total thyroidectomy with CND via BABA had same safety and effect as conventional open procedure for patients with papillary thyroid microcarcinoma, but its cosmetic effect was more satisfactory.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by the grants from the Third Batch Special Foundation of China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 201003759), and the President Funding of Jinan Military General Hospital of PLA (No. 2011 M 03 and No. 2013 ZD 05).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by: Xin Chen

REFERENCES

- 1.Kang SW, Jeong JJ, Yun JS, Sung TY, Lee SC, Lee YS, et al. Robot-assisted endoscopic surgery for thyroid cancer: Experience with the first 100 patients. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2399–406. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0366-x. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0366-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bae DS, Suh BJ, Park JK, Koo do H. Technical, oncological, and functional safety of bilateral axillo-breast approach (BABA) robotic total thyroidectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2016;26:253–8. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000262. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim WW, Jung JH, Park HY. A single surgeon's experience and surgical outcomes of 300 robotic thyroid surgeries using a bilateral axillo-breast approach. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111:135–40. doi: 10.1002/jso.23793. doi: 10.1002/jso.23793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sung ES, Ji YB, Song CM, Yun BR, Chung WS, Tae K. Robotic Thyroidectomy: Comparison of a postauricular facelift approach with a gasless unilateral axillary approach. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;154:997–1004. doi: 10.1177/0194599816636366. doi: 10.1177/0194599816636366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakkar S, Frustaci G, Papini P, Fregoli L, Matteucci V, Materazzi G, et al. Track recurrence after robotic transaxillary thyroidectomy: A case report highlighting the importance of controlled surgical indications and addressing unprecedented complications. Thyroid. 2016;26:559–61. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0561. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee HY, Richmon JD, Walvekar RR, Holsinger C, Kim HY. Robotic transoral periosteal thyroidectomy (TOPOT): Experience in two cadavers. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2015;25:139–42. doi: 10.1089/lap.2014.0543. doi: 10.1089/lap.2014.0543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He Q, Zhu J, Zhuang D, Fan Z. Robotic total parathyroidectomy by the axillo-bilateral-breast approach for secondary hyperparathyroidism: A feasibility study. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2015;25:311–3. doi: 10.1089/lap.2014.0234. doi: 10.1089/lap.2014.0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berber E, Bernet V, Fahey TJ, 3rd, Kebebew E, Shaha A, Stack BC, Jr, et al. American Thyroid Association Statement on remote-access thyroid surgery. Thyroid. 2016;26:331–7. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0407. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caruso G, Spinosi MC, Cambi J, Passali FM, Bellussi L, Passali D. Open versus robotic thyroidectomy: Is it really a controversial choice? Kulak Burun Bogaz Ihtis Derg. 2015;25:375–6. doi: 10.5606/kbbihtisas.2015.49035. doi: 10.5606/kbbihtisas.2015.49035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perrier ND. Why I have abandoned robot-assisted transaxillary thyroid surgery. Surgery. 2012;152:1025–6. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.08.060. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arora A, Garas G, Sharma S, Muthuswamy K, Budge J, Palazzo F, et al. Comparing transaxillary robotic thyroidectomy with conventional surgery in a UK population: A case control study. Int J Surg. 2016;27:110–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.01.071. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He Q, Zhuang D, Zheng L, Zhou P, Chai J, Lv Z. Harmonic focus in total thyroidectomy plus level III-IV and VI dissection: A prospective randomized study. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:141. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-9-141. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-9- [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hüscher CS, Chiodini S, Napolitano C, Recher A. Endoscopic right thyroid lobectomy. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:877. doi: 10.1007/s004649900476. doi:10.1007/s004649900477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwon H, Yi JW, Song RY, Chai YJ, Kim SJ, Choi JY, et al. Comparison of bilateral axillo-breast approach robotic thyroidectomy with open thyroidectomy for Graves’ disease. World J Surg. 2016;40:498–504. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3403-7. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3403-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giannopoulos G, Kang SW, Jeong JJ, Nam KH, Chung WY. Robotic thyroidectomy for benign thyroid diseases: A stepwise strategy to the adoption of robotic thyroidectomy (gasless, transaxillary approach) Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2013;23:312–5. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31828b8b20. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31828b8b20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo P, Tang Z, Ding Z, Chu G, Yao H, Pan T, et al. Transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy with central neck dissection: Experimental studies on human cadavers. Chin Med J. 2014;127:1067–70. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.20133200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu SY, Lang BH. Revisiting robotic approaches to endocrine neoplasia: Do the data support their continued use? Curr Opin Oncol. 2016;28:26–36. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000245. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu SY, Ng EK. Robotic versus open thyroidectomy for differentiated thyroid cancer: An evidence-based review. Int J Endocrinol 2016. 2016:4309087. doi: 10.1155/2016/4309087. doi: 10.1155/2016/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stang MT, Perrier ND. Robotic thyroidectomy: Do it well or don’t do it. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:806–8. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.2253. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taskin HE, Arslan NC, Aliyev S, Berber E. Robotic endocrine surgery: State of the art. World J Surg. 2013;37:2731–9. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2154-y. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2154-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Terris DJ, Duke WS. Robotic and remote access thyroidectomy: A time to pause. World J Surg. 2013;37:1582–3. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2099-1. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levi Sandri GB, Coluzzi M, Caporilli D, de Luca A, Guerra F. Robotic thyroidectomy: Is it a futile surgical approach? Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2015;25:268. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000160. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inabnet WB., 3rd Robotic thyroidectomy: Must we drive a luxury sedan to arrive at our destination safely? Thyroid. 2012;22:988–90. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.2210.com2. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.2210.com2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Son H, Park S, Lee CR, Lee S, Kim JW, Kang SW, et al. Factors contributing to surgical outcomes of transaxillary robotic thyroidectomy for papillary thyroid carcinoma. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:3134–42. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3567-x. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3567-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma A, Albergotti WG, Duvvuri U. Applications of evolving robotic technology for head and neck surgery. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2016;125:207–12. doi: 10.1177/0003489415606448. doi: 10.1177/0003489415606448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Byeon HK, Holsinger FC, Tufano RP, Chung HJ, Kim WS, Koh YW, et al. Robotic total thyroidectomy with modified radical neck dissection via unilateral retroauricular approach. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:3872–5. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3896-y. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3896-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hinson AM, Kandil E, O’Brien S, Spencer HJ, Bodenner DL, Hohmann SF, et al. Trends in robotic thyroid surgery in the United States from 2009 through 2013. Thyroid. 2015;25:919–26. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0066. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee HY, Yang IS, Hwang SB, Lee JB, Bae JW, Kim HY. Robotic thyroid surgery for papillary thyroid carcinoma: Lessons learned from 100 consecutive surgeries. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2015;25:27–32. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3182a2b0ae. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3182a2b0ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang YC, Liu K, Xiong JJ, Zhu JQ. Robotic thyroidectomy versus conventional open thyroidectomy for differentiated thyroid cancer: Meta-analysis. J Laryngol Otol. 2015;129:558–67. doi: 10.1017/S002221511500122X. doi: 10.1017/S002221511500122X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He Q, Zhu J, Fan Z, Zhuang D, Zheng L, Zhou P, et al. Robotic thyroidectomy with central neck dissection using axillo-bilateral-breast approach: A comparison to open conventional approach (in Chinese) Chin J Surg. 2016;54:51–5. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-5815.2016.01.013. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-5815.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kandil E, Saeed A, Mohamed SE, Alsaleh N, Aslam R, Moulthrop T. Modified robotic-assisted thyroidectomy: An initial experience with the retroauricular approach. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:767–71. doi: 10.1002/lary.24786. doi: 10.1002/lary.24786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]