Abstract

AIM:

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is considered the ‘gold standard’ intervention for gall bladder (GB) diseases. However, to avoid serious biliovascular injury, conversion is advocated for distorted anatomy at the Calot's triangle. The aim is to find out whether our technique of laparoscopic modified subtotal cholecystectomy (LMSC) is suitable, with an acceptable morbidity and outcome.

PATIENTS AND METHODS:

A retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data of 993 consecutive patients who underwent cholecystectomy was done at a large District General Hospital (DGH) between August 2007 and January 2015. The data are as follows: Patient's demographics, operative details including intra- and postoperative complications, postoperative stay including follow-up that was recorded and analysed.

RESULTS:

A total of 993 patients (263 males and 730 female) were included. The median age was 52*(18-89) years. Out of the 993 patients, 979 (98.5%) and 14 (1.5%) were listed for laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy, respectively. Of the 979 patients, 902 (92%) and 64 (6.5%) patients underwent LC ± on-table cholangiography (OTC) and LMSC ± OTC, respectively, with a median stay of 1* (0-15) days. Of the 64 patients, 55 (86%) had dense adhesions, 22 (34%) had acute inflammation, 19 (30%) had severe contraction, 12 (19%) had empyema, 7 (11%) had Mirizzi's syndrome and 2 (3%) had gangrenous GB. The mean operative time was 120 × (50-180) min [Table 1]. Six (12%) patients required endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) postoperatively, and there were four (6%) readmissions in a follow-up of 30 × (8-76) months. The remaining 13 (1.3%) patients underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy converted to an open cholecystectomy. The median stay for open/laparoscopic cholecystectomy converted to open cholecystectomy was 5 × (1-12) days.

CONCLUSION:

Our technique of LMSC avoided conversion in 6.5% patients and believe that it is feasible and safe for difficult GBs with a positive outcome.

Keywords: Cholecystectomy, laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC), laparoscopic retrograde cholecystectomy (LRC)

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) was introduced into the field of general surgical practice in the late 1980s and is universally accepted as the ‘gold standard’ treatment for symptomatic gall bladder (GB) diseases.[1,2] However, conversion that minimises the risk of biliary and vascular injury, is required in 5-20% of cases,[3,4,5] especially in patients with dense omental adhesions at the Calot's triangle, fibrosed and shrunken GBs, empyema and gangrene of the GB.[6]

The identification and safe dissection of Calot's triangle is essential to minimise or avoid vascular or biliary damage, and conversion is the adopted norm when the biliary anatomy is unidentifiable.[7] The available evidence still shows an increased incidence of biliary and vascular injury even with an open approach, and the conversion does not necessarily improve the exposure of biliary anatomy but definitely increases postoperative morbidity that includes pain, wound infection, delayed mobility, increased incidence of adhesion and incisional herniae.[8]

Retrograde (‘fundus first’) cholecystectomy is a safe and an accepted option for difficult GBs with the open approach. Laparoscopic retrograde cholecystectomy (LRC), although technically feasible, is a much more complex procedure, hence, is not widely practised but may be considered an alternative to conversion in cases where there is distorted biliary anatomy.[9,10]

We present here a single-institution experience of our technique of laparoscopic modified subtotal cholecystectomy (LMSC) that avoided conversion for difficult GBs with a positive long-term outcome.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This is a retrospective study of prospectively collected data of 993 consecutive patients who underwent cholecystectomy in the upper gastrointestinal unit of William Harvey Hospital, Ashford, Kent, a large district general hospital between August 2007 and January 2015. Study included both elective and emergency cholecystectomies on adult patients. Patient demographics, operative details (reason for modified subtotal cholecystectomy), duration of the procedure, length of stay, immediate and long-term complications were recorded. This was a retrospective observational study, and this study was deemed to be a service evaluation and no further ethics approval was required.

The patients were counselled and consented prior to the surgery, and routine preoperative investigations included haematological, biochemical analysis and ultrasonography. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), computed tomography (CT) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) were performed when indicated.

The decision to adopt our technique of LMSC was made on the basis of intraoperative findings where it was felt unsafe to approach the Calot's triangle due to severe inflammatory changes/distorted anatomy/‘frozen’ triangle to avoid vascular or biliary damage.

Our operative technique

The patients are placed in the reverse Trendelenburg position with 15°-20° left-sided rotation, and the surgeon stands on the left to operate. Two 12-mm and two 5-mm ports are placed in their standard positions for LC. The assessment of the right upper quadrant is followed by a careful dissection of omentum, colon, stomach and/or duodenal adhesions to expose the GB; the failure to achieve exposure of the GB results in conversion.

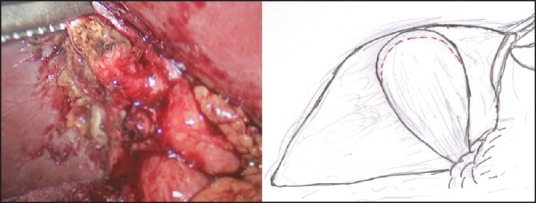

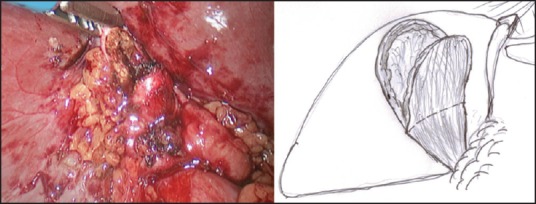

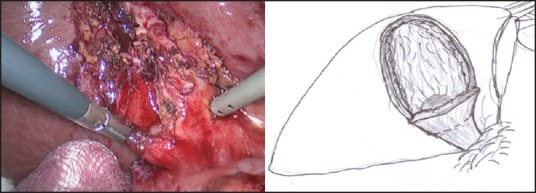

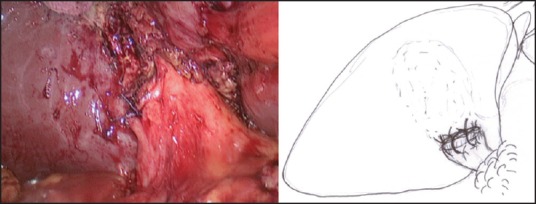

In those patients where the ‘critical view of safety’ (ability to identify or exposure the structures at the Calot's triangle) cannot be achieved, LMSC is undertaken to avoid a conversion. In our ‘fundus first approach’ [Figure 1], the fundus is opened using a monopolar diathermy to allow drainage of pus/infected bile/stones, which are either aspirated or collected in a bag. This is followed by diathermy splitting of the GB into two halves [Figure 2]. The GB posterior wall attachment to the liver provides traction, while the anterior wall is dissected down to the Hartmann's pouch and is transected. The liver is then retracted against a tonsil swab to avoid damage and the posterior GB wall is freed from the liver bed with the help of the diathermy. If the posterior wall is difficult to separate from the liver bed (i.e., in cases with fibrosed or intrahepatic GBs), it is cauterised. In our opinion, the ‘inside view of the gallbladder’ [Figure 3] allows safe dissection and avoids or minimises the risk of damage to the portal structures and also allows on-table cholangiography (OTC) to be performed in selected cases. This is followed by an intracorporeal stitch or endoloop closure of the cystic duct/small GB remnant [Figure 4]. A thorough wash out is performed and a sub-hepatic drain is inserted prior to port site wound closure using the standard technique.

Figure 1.

‘Fundus first approach’—fundus of the gallbladder opened using monopolar diathermy

Figure 2.

Diathermy splitting of the gall bladder

Figure 3.

‘Inside view of gallbladder’—to visualise the Hartmann's pouch and the cystic duct

Figure 4.

Intracorporeal suturing of the gall bladder stump

All patients who undergo LMSC receive 72 h of 1.2 gm of co-amoxiclav or 750 mg of Cefuroxime (if allergic to penicillin) three times daily and three days of single dose of Gentamicin (3-5 mg/kg of bodyweight) and all patients received low-molecular weight heparin 40 mcg sub cutaneous 6 h after surgery.

Drains are removed in 24/48 h on observation of minimal serous/serosanguineous drainage (<50 mL) and are only left longer in patients with drainage of bile requiring ERCP and stenting after the surgery.

In this study, all patients who underwent LMSC were contacted over telephone and were reviewed in a clinic if indicated.

RESULTS

A total of 993 patients [263(26%) males and 730(74%) females] with a median age of 52*(18-89) years were included. Of the 993 patients, 979 (98.5%) and 14 (1.5%) patients were listed for laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy [patients with multiple laparotomies (≥3 upper abdomen) and/or having right-sided stomas], respectively.

Of the 979 patients, 902 (92%) had LC with or without OTC, 64 (6.5%) underwent LMSC with or without OTC and the remaining 13 patients (1.3%) were converted to an open procedure for their severely distorted biliary anatomy.

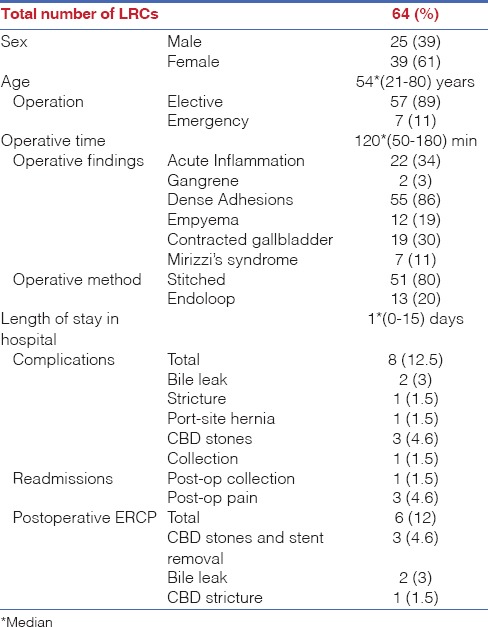

Of the 64 patients undergoing LMSC, 25 (39%) were males and 39 (61%) were females [median age 54*(21-80) years]. Fifty-seven (91%) patients were elective and seven (11%) underwent emergency operations [Table 1]. None from this group needed conversion to an open procedure.

Table 1.

Patient demographics, indications and outcomes

The patients who underwent LMSC often had multiple pathological findings that prompted the procedure: 55 (86%) had dense adhesions, 22 (34%) had acute inflammation, 19 (30%) had severely contracted GB, 12 (19%) had empyema of the GB, 7 (11%) had Mirizzi's syndrome and 2 (3%) had gangrenous GB. The median operating time for LMSC was 120*(50-180) min [Table 1].

The median length of stay for laparoscopic and open cholecystectomies (laparoscopic converted to open and all open procedures) were 1*(0-15) day and 5*(1-12) days, respectively.

The median follow-up for patients undergoing LMSC was 30 (8-76) months: Six (9%) patients required postoperative ERCP [three (4.6%) for common bile duct (CBD) stones and stent removal, two (3%) for bile leak and one (1.5%) for CBD stricture]; there were four (6%) re-admissions [three (4.6%) for pain and one (1.5%) for a collection] [Table 1].

DISCUSSION

‘Critical view of safety’ (positive identification of biliary anatomy) prior to transection of the cystic duct and artery can be challenging in the face of distorted or obscured biliary anatomy. In the prelaparoscopic era, ‘fundus first approach’ ending in subtotal cholecystectomy for difficult GBs was well accepted as a safe and definitive procedure.[11] LC is currently accepted as the ‘gold standard’ treatment for GB diseases, it may still be considered unsafe and dangerous by some when faced with difficult biliary anatomy, thus, resorting to an open procedure.

However, there are concerns that the newer generation of surgeons may have little or no experience with the open procedure and conversion would not necessarily provide a better anatomical view, especially for the patients with a higher BMI, potentially posing an even higher risk of complications.[12] Bilio-vascular injury for LC is less than 1% with bile duct and vascular injury recorded individually being 0.6% and 0.25%, respectively.[13,14] The evidence has already shown open procedure to be associated with increased postoperative morbidity due to the higher incidence of wound infection, postoperative pain, slow recovery and a prolonged hospital stay.

Common reasons for conversion include dense fibrotic adhesions at the Calot's triangle, fibrosed GB, empyema and gangrene of the GB, which lead to unclear anatomy and difficulties in dissecting the Calot's triangle.[15]

The surgical strategy may be changed to LRC when there are dense fibrotic adhesions at the Calot's triangle, a fibrosed GB, Mirizzi's syndrome, empyema or gangrene of the GB or unclear biliary anatomy.[16] In our series, majority of the patients had dense adhesions at the Calot's triangle leading to unidentifiable biliary anatomy. In addition, 30% had a contracted GB, 19% had empyema of the GB, 11% had Mirizzi's syndrome and 3% had gangrenous GB.

Several operative techniques have been described to address difficult biliary anatomy.[17] They include excision of the anterior wall of the GB and leaving the posterior wall attached to the liver,[7] excision of both the anterior and posterior GB walls following dissection and the GB divided at Hartmann's pouch.[16,18] Irrespective of the technique, the GB stump are either left open[19,20] or closed using endoloop,[21] an intracorporeal stitch[16] or stapled.[16,22] The mucosa of the posterior wall of the remnant GB is diathermised[23] or left alone[16,24] with or without a drain in situ.

Our technique of LMSC in bisecting the GB and carried down to the Hartmann's pouch have distinct advantages:

Posterior wall of the GB attached to the liver allows safe traction for better exposure and dissection and avoids risk of liver damage,

‘Inside view of the gall bladder’ allows clear identification of the GB mucosa and junction between the Hartmann's pouch and the cystic duct for safe dissection and subsequent transection or suture application.

This approach allows dissection to be performed well away from the vital portal structures and thus avoids any biliovascular injuries.

LRC has been demonstrated to be safe and effective for avoiding a major bile duct injury.[25] A common complication after LRC is bile leak, which has been reported in up to 16% of cases,[7,23] either from the open cystic duct stump or from the remnant posterior wall. We advocate routine closure of the cystic duct stump/GB remnant through the application of either an endoloop or an intracorporeal absorbable suture and have recorded a 4.6% incidence of bile leak that is favourable compared to the published literature.

The other concerns raised about LRC include the neo-formation of gallstones or retained gallstones in the remnant GB and slippage of gallstones into the CBD.[7] Literature has reported recurrent symptomatic GB disease to occur in up to 5% of patients.[17] In our series with a median follow-up of 30 months, no neo-formation of gallstones have been recorded and as described above the ‘inside view of the gallbladder’ and selective use of an on table cholangiogram avoided the complication of retained gallstones in the remnant GB. Three (6%) patients who had CBD stones identified during the on table cholangiogram were successfully treated through ERCP in the immediate postoperative period. Other known complication recorded includes CBD stricture, with an overall reported incidence of 2-4%. Here, only one (1.5%) patient had developed a CBD stricture, which was treated successfully endoscopically.

LMSC, although shown to be safe and effective for avoiding major bile duct injury, is definitely technically more challenging than a simple LC and should be approached with caution. There still remains a controversy as to whether conversion to an open procedure or closure with referral to a specialist upper GI/HPB unit is most suitable in difficult cases: A multicentric randomised controlled study would possibly prove the benefits of LMSC to the wider community for a universal acceptance.

Although a retrospective and a single centre study that is considered a weakness, this study demonstrates LMSC: A feasible and a safe alternative to conversion for difficult GBs with a positive outcome.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Begos DG, Modlin IM. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: From gimmick to gold standard. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1994;19:325–30. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199412000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blum CA, Adams DB. Who did the first laparoscopic cholecystectomy? J Minim Access Surg. 2011;7:165–8. doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.83506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey RW, Zucker KA, Flowers JL, Scovill WA, Graham SM, Imbembo AL. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Experience with 375 consecutive patients. Ann Surg. 1991;214:531–41. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199110000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Comitalo JB. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy and newer techniques of gallbladder removal. JSLS. 2012;16:406–12. doi: 10.4293/108680812X13427982377184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gurusamy KS, Davidson C, Gluud C, Davidson BR. Early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for people with acute cholecystitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6:CD005440. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005440.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kama NA, Doganay M, Dolapci M, Reis E, Atli M, Kologlu M. Risk factors resulting in conversion of laparoscopic cholecystectomy to open surgery. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:965–8. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-0008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Philips JA, Lawes DA, Cook AJ, Arulampalam TH, Zaborsky A, Menzies D, et al. The use of laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy for complicated cholelithiasis. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1697–700. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9699-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanabria JR, Clavien PA, Cywes R, Strasberg SM. Laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy: A matched study. Can J Surg. 1993;36:330–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis B, Castaneda G, Lopez J. Subtotal cholecystectomy versus total cholecystectomy in complicated cholecystitis. Am Surg. 2012;78:814–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamura A, Ishii J, Katagiri T, Maeda T, Kubota Y, Kaneko H. Effectiveness of laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy: Perioperative and long-term postoperative results. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60:1280–3. doi: 10.5754/hge13094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katsohis C, Prousalidis J, Tzardinoglou E, Michalopoulos A, Fahandidis E, Apostolidis S, et al. Subtotal cholecystectomy. HPB Surg. 1996;9:133–6. doi: 10.1155/1996/14515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolf AS, Nijsse BA, Sokal SM, Chang Y, Berger DL. Surgical outcomes of open cholecystectomy in the laparoscopic era. Am J Surg. 2009;197:781–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deziel DJ, Millikan KW, Economou SG, Doolas A, Ko ST, Airan MC. Complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A national survey of 4,292 hospitals and an analysis of 77,604 cases. Am J Surg. 1993;165:9–14. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80397-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strasberg SM. Error traps and vasculo-biliary injury in laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2008;15:284–92. doi: 10.1007/s00534-007-1267-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bingener-Casey J, Richards ML, Strodel WE, Schwesinger WH, Sirinek KR. Reasons for conversion from laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy: A 10-year review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2002;6:800–5. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(02)00064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chowbey PK, Sharma A, Khullar R, Mann V, Baijal M, Vashistha A. Laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy: A review of 56 procedures. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2000;10:31–4. doi: 10.1089/lap.2000.10.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henneman D, da Costa DW, Vrouenraets BC, van Wagensveld BA, Lagarde SM. Laparoscopic partial cholecystectomy for the difficult gallbladder: A systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:315–58. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2458-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakajima J, Sasaki A, Obuchi T, Baba S, Nitta H, Wakabayashi G. Laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy for severe cholecystitis. Surg Today. 2009;39:870–5. doi: 10.1007/s00595-008-3975-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clemente G. Laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy without cystic duct ligation (Br J Surg 2007; 94: 1527-1529) Br J Surg. 2008;95:534. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinha I, Smith ML, Safranek P, Dehn T, Booth M. Laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy without cystic duct ligation. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1527–9. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michalowski K, Bornman PC, Krige JE, Gallagher PJ, Terblanche J. Laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy in patients with complicated acute cholecystitis or fibrosis. Br J Surg. 1998;85:904–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee MR, Chun HT, Roh YH, Kim SH, Kim YH, Cho SH, et al. Application of an endo-GIA for ligation of the cystic duct during difficult laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:285–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horiuchi A, Watanabe Y, Doi T, Sato K, Yukumi S, Yoshida M, et al. Delayed laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis with severe fibrotic adhesions. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2720–3. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9879-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ransom KJ. Laparoscopic management of acute cholecystitis with subtotal cholecystectomy. Am Surg. 1998;64:955–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hussain A. Difficult laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Current evidence and strategies of management. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21:211–7. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e318220f1b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]