Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is the most commonly performed ‘standalone’ bariatric procedure in India. Staple line gastric leaks occur infrequently but cause significant and prolonged morbidity. The aim of this retrospective study was to analyse the management of patients with a gastric leak after LSG for morbid obesity at our institution.

PATIENTS AND METHODS:

From February 2008 to 2014, 650 patients with different degrees of morbid obesity underwent LSG. Among these, all those diagnosed with a gastric leak were included in the study. Patients referred to our institution with gastric leak after LSG were also included. The time of presentation, site of leak, investigations performed, treatment given and time of closure of all leaks were analysed.

RESULTS:

Among the 650 patients who underwent LSG, 3 (0.46%) developed a gastric leak. Two patients were referred after LSG was performed at another institution. The mean age was 45.60 ± 15.43 years. Mean body mass index (BMI) was 44.79 ± 5.35. Gastric leak was diagnosed 24 h to 7 months after surgery. One was early, two were intermediate and two were late leaks. Two were type I and three were type II gastric leaks. Endoscopic oesophageal stenting was used variably before or after re-surgery. Re-surgery was performed in all and included stapled fistula excision (re-sleeve), suture repair only or with conversion to roux-en-Y gastric bypass or fistula jujenostomy. There was no mortality.

CONCLUSION:

Leakage closure time may be shorter with intervention than expectant management. Sequence and choice of endoscopic oesophageal stenting and/or surgical re-intervention should be individualized according to clinical presentation.

Keywords: Bariatric surgery, gastric leak, morbid obesity, sleeve gastrectomy

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is emerging to be one of the commonly performed bariatric procedures worldwide for patients with different degrees of obesity. This restrictive procedure has several advantages. It is technically simpler to perform without the need of an anastomosis. It induces a reduction in ghrelin causing appetite suppression, which adds to the effect of restriction.[1,2,3,4] It has been reported to have a lower morbidity and mortality rate in comparison to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or biliopancreatic diversion with or without duodenal switch.[5] It can be performed concomitantly with other procedures.[6]

LSG can be associated with three significant complications, which include staple line gastric bleeding, staple line gastric leaks and gastric strictures. Of these, a gastric leak after sleeve gastrectomy is associated with significant and prolonged morbidity, remaining one of the most feared complications. A gastric leak can present as peritonitis, abscesses, cutaneous or other fistulas, sepsis, organ failure and even death. Fortunately it is an infrequent complication of LSG. However, as a consequence, the management of such patients cannot be clearly recommended. Analysing patients with this problem can help define a clinical approach for management and possible preventive measures.

The aim of this retrospective study was to analyse the management of patients with a gastric leak after LSG for morbid obesity at our institution.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study population

From February 2008 to 2014, 650 patients with morbid obesity with a mean body mass index of 44.64 ± 9.01 kg/m2 underwent LSG. Among them, all those diagnosed with a gastric leak were included in the study. Patients referred to our institution with gastric leak after LSG were also included.

Surgical technique of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy

After a closed 16 mmHg pneumoperitoneum with a Veress needle, five trocars were inserted: A 5-mm sub-xiphoid trocar (served as liver retractor); a 12-mm right upper quadrant trocar (served as a working port, served to fire the endo-GIA stapler and served to remove the specimen); a 10-mm supra-umbilical trocar (served as camera port); a 5-mm left upper quadrant trocar (served as another working channel); and a 5-mm left subcostal anterior axillary line trocar (served for counter retraction). LSG was performed by dividing the greater omentum of the greater curvature and the short gastric and fundal attachments using a Harmonic Ace device (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH, USA) or a Ligasure device (Covidien Ltd, Norwalk, Connecticut, USA), beginning 4-5 cm proximal to the pylorus. Once this was completed, a 36-Fr bougie was introduced by the anaesthesiologist into the stomach, and advanced along the lesser curvature into the pyloric channel. An endo-GIA stapler (Echelon: 60-mm stapling; Ethicon End-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH, USA) was introduced through the 12-mm port, which was located at the right quadrant, to begin the gastric tubulisation by division of the antrum 4-5 cm proximal to the pylorus followed by serial firing of linear staplers resulting in a small gastric tubular pouch. Reinforcement was not routinely performed. To determine leakage, flow was transiently blocked into the duodenum with bowel forceps at the pyloric channel after instilling saline in the abdominal cavity and an air test was performed by insufflating air through the ryle's tube inserted in the gastric pouch. The resected specimen was removed through the 12-mm port at the right upper abdominal quadrant. Drains were not routinely placed.

Postoperative radiological screening

In all patients, a radiological evaluation was performed on the first postoperative day using diluted GASTROGRAFIN® Oral Solution (diatrizoate meglumine/diatrizoate sodium). While standing, the patient swallowed 100 mL of solution, and the characteristics of the tubular stomach (i.e., size, emptying and presence or absence of leak or stricture) were evaluated with fluoroscopy.

Classification of gastric leaks

We used the classifications proposed by Csendes et al. and Burgos et al. of gastric leaks based on the time of appearance after surgery, clinical severity and location of leaks.[7,8,9]

Based on clinical presentation, gastric leaks were classified as follows:

Type I (Subclinical): Presence of leakage without early septic complications corresponding to drainage through a fistulous track and/or without generalised dissemination to the pleural or abdominal cavity with or without the appearance of contrast medium in any of the abdominal drains.

Type II (Clinical): Presence of leakage with early septic complications corresponding to drainage by an irregular pathway (no well-formed fistulous tract) and a more generalised dissemination into the pleural or abdominal cavity with or without appearance of contrast medium in any of the abdominal drains.

Based on the time when the leaks presented, they were classified as follows:

Early (leaks appearing 1-3 days after surgery).

Intermediate (leaks appearing 4-7 days after surgery).

Late (leaks appearing ≥8 days after surgery).

Data collection

In all patients with the presence of a gastric leak, the information collected included patient demographics, anthropometrics, details of comorbidities, operative and perioperative data, time of presentation, site of leak, details of methods used to detect and manage the leaks, time of closure, interval between surgery and detection and interval between detection and leak closure.

RESULTS

Individual case summaries

Patient 1 (Type 2, intermediate gastric leak just beyond oesophago-gastric junction treated with laparoscopic drainage, fistula exclusion with a long, fully covered oesophageal stent and laparoscopic suturing of gastric fistula)

Case details: A 52-year-old male, at an outside hospital presented with sepsis on the sixth postoperative day after LSG. Re-laparoscopy revealed a fistula just beyond the oesophago-gastric junction, which was drained. Fistula was stented with a Niti-S™ Mega™ oesophageal stent (Taewoong Medical, Seoul, Korea), complicated by bleeding on the fifth postoperative day from stent erosion into the duodenal mucosa needing removal. He was referred to us at 3 months after LSG with a controlled gastric fistula. Endoscopy revealed a small opening just beyond the oesophago-gastric junction. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the abdomen revealed minimal leak from the oesophago-gastric junction within a walled-off cavity. The patient did not gave consent for re-stenting. Re-laparoscopy with closure of fistulous opening in two layers with feeding jejunostomy was performed. In 72 h, there was a leak again with the same output as before. Drainage gradually decreased and stopped 6 weeks postoperatively with the absence of a leak on imaging. The patient was diagnosed on the sixth postoperative day and the time till the fistula closure was 5.5 months.

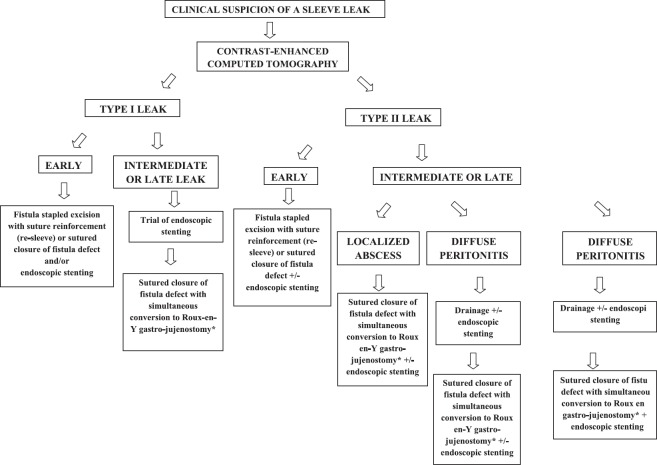

Patient 2 [Type 2, intermediate gastric leak, just beyond oesophago-gastric junction and at mid-sleeve, treated with laparoscopic drainage, fistula jujenostomy and stapled excision of gastric fistula (re-sleeve)]

Case details: A 52-year-old woman, with a body mass index (BMI) of 48 kg/m2 without co-morbidities at an outside hospital presented on the seventh postoperative day with sepsis after LSG. Laparotomy revealed a fistula (details not available) and drainage with feeding jujenostomy was performed. Endoscopy revealed narrowing at the incisura, which was dilated. Postoperatively a gastro-cutaneous fistula developed and was treated conservatively. She was referred to us at 4 months after LSG with a controlled gastro-cutaneous fistula through the middle of a midline laparotomy scar. CECT scan showed a fistula from mid-body stomach leading to the skin through a well-formed fistula tract [Figure 1a]. Endoscopy revealed a large opening over the anterior gastric wall at mid-body with narrowing at the incisura. Re-laparotomy revealed a cutaneous fistulous opening arising from a mid-body gastric fistula [Figure 1b and c]. A side-to-side fistula loop gastro-jujenostomy was performed [Figure 1d]. Postoperatively a small bile leak developed from the laparotomy wound 1 month later. Endoscopy revealed a fistula just beyond the oesophago-gastric junction, probably a missed sealed fistula. After 8 weeks, re-laparotomy with excision of the fistula site with a linear stapler (re-sleeve) and suture reinforcement was performed. Loop gastro-jujenostomy was converted to a Roux-en-Y configuration. The leak settled postoperatively with insignificant drain output and absence of a leak on imaging. The patient had a poor general condition, improved gradually and was discharged from the hospital 1 month later. The patient was diagnosed on the sixth postoperative day and the time from diagnosis to fistula closure was 9 months.

Figure 1.

(a) Cross section of contrast enhanced computed tomography scan scan showing a well-formed fistulous tract leading from the mid-sleeve to the midline laparotomy wound (b and c) Intraoperative photograph showing the gastro-cutaneous fistula opening at midline laparotomy scar with a nasogastric tube threaded across seen to arise from a large mid-body fistula at laparotomy (d) Intraoperative photograph showing the side-to-side fistula loop gastro-jujenostomy

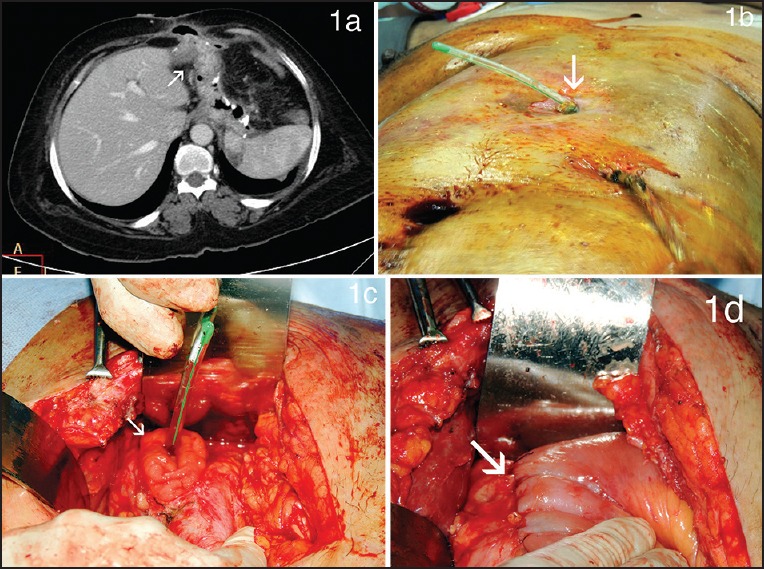

Patient 3 (Type 2, late leak just beyond oesophago-gastric junction, treated with laparoscopic drainage, exclusion with covered, self-expanding metallic stent and laparoscopic suturing of fistula site with conversion to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass)

Case details: An 18-year-old woman with a BMI of 44.68 kg/m2 with hypothyroidism and polycystic ovarian disease underwent LSG at our institution. Routine air leak test and gastrografin study showed no leak. She was readmitted on postoperative day 15 with fever, chills, leucocytosis and abdominal pain. Abdominal ultrasound was normal. A CECT scan performed because of high suspicion showed a 5 × 6.2 cm collection in the left sub-diaphragmatic region with air but no leak of contrast [Figure 2a]. Endoscopy did not reveal any fistula. At diagnostic laparoscopy, the abscess was drained but no obvious fistula was noted and the air leak test was negative. In 48 h, an obvious leak of saliva was noted in the drainage. Repeat imaging revealed a leak just beyond oesophago-gastric junction. At re-laparoscopy, a small fistulous opening was identified at the oesophago-gastric junction closed by suturing of the defect in two layers [Figure 2b]. Concomitant Roux-en-Y bypass was performed to decompress the stomach to aid healing. An ante-colic, 100-cm Roux-en-Y limb was anastomosed end-to-side after dividing across the sleeve to create a gastric pouch [Figure 2c and d]. A Niti-S™ Beta™ oesophageal stent (Taewoong Medical, Seoul, Korea) was also placed at the site of the sutured fistula repair. A feeding jujenostomy was performed. Drainage of the fistula decreased postoperatively to an insignificant drain output and absence of a leak on imaging in 12 days. After 7 weeks, the stent was removed. The patient was diagnosed on the 15th postoperative day and the time from diagnosis to fistula closure was 1 month.

Figure 2.

(a) Cross section of contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan showing a left sub-diaphragmatic collection with air within, with no leak of contrast (b) Intraoperative photograph showing sutured repair of the fistula site (c and d) Intraoperative photograph showing creation of a gastric pouch by dividing the sleeve across and conversion to a Roux-en-Y bypass

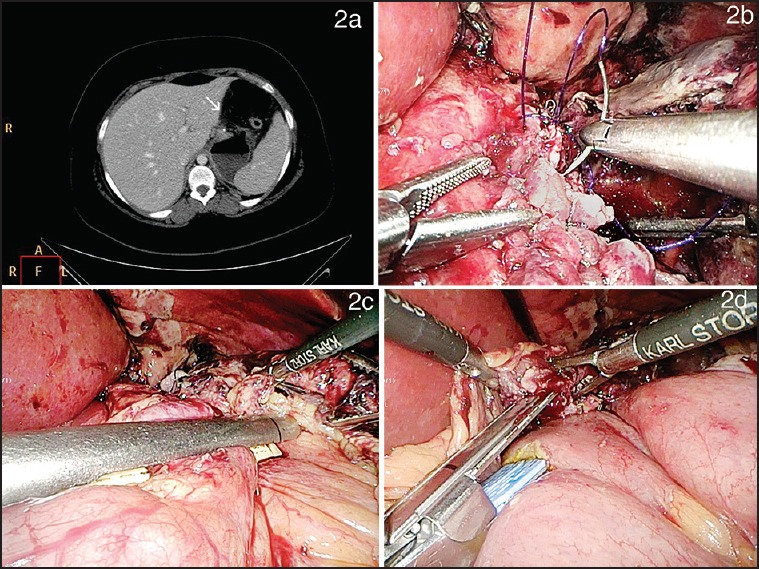

Patient 4 [Type 1, early leak, just beyond oesophago-gastric junction with staple line bleed treated with evacuation of haematoma and stapled excision of the fistula site (re-sleeve)]

Case details: A 53-year-old male with a BMI of 39.5 m2 with type 2 diabetes mellitus, systemic hypertension, dyslipidemia and gout underwent a LSG at our institution, Intraoperative air leak test was negative. Postoperative gastrografin swallow revealed a doubtful leak. The patient had mild persistent tachycardia and low haemoglobin. A CECT scan showed evidence of 10 × 8 cm sub-diaphragmatic collection suggestive of a haematoma with a small leak of contrast from the most proximal end of the staple line within the haematoma [Figure 3a]. The patient was re-explored and the haematoma was evacuated [Figure 3b]. The air leak test did not reveal any obvious site of leak. The stomach just beyond the oesophago-gastric junction was re-sleeved with a linear stapler [Figure 3c]. The site of bleeding was identified and controlled [Figure 3d]. The entire staple line was reinforced with sutures and a drain placed next to the staple line. Drainage amount decreased to a minimum by 5 days and was removed. The patient was diagnosed with a sleeve leak on the first postoperative day and the time from diagnosis to fistula closure was 48 h.

Figure 3.

(a) Cross section of contrast-enhanced CT scan revealed a sub-diaphragmatic collection suggestive of a haematoma with a small leak of contrast within the haematoma (b) Intraoperative view of staple line haematoma (c) Intraoperative photograph showing the stomach just beyond oesophago-gastric junction being re-sleeved with a linear stapler (d) Intraoperative photograph showing site of staple line bleeding managed by suture ligation

Patient 5 (Type 1, late leak just beyond oesophago-gastric junction forming a gastro-bronchial fistula, treated with fistula exclusion with long covered self-expanding metallic oesophageal stent and laparoscopic suturing of the fistula site with conversion to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.)

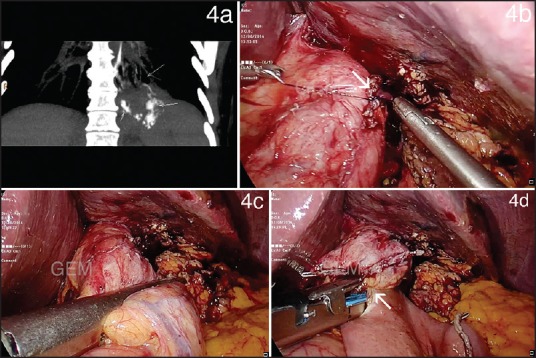

Case details: A 53-year-old woman with a BMI of 50.2 underwent LSG at our institution. She underwent regular follow-up and had no complaints with a 7 months percentage of excess weight loss of 55%. At 7 months, she presented with fever and cough and investigation revealed a left lower lobe consolidation. Ultrasound imaging of the abdomen was normal. She was treated conservatively. The same however, recurred in 1 month. A CECT performed revealed patchy consolidation of the left posterior basal segment with mild left pleural effusion, two small left sub-diaphragmatic collections with air pockets, with leak of oral contrast within the sub-diaphragmatic collections draining to a bronchus in left postero-basal segment [Figure 4a]. Endoscopy performed revealed a fistulous opening just beyond the oesophago-gastric junction. The patient was stented with a Niti-S™ Mega™ oesophageal stent (Taewoong Medical, Seoul, Korea), which did not lead to resolution of the leak after a trial of 6 weeks after which it was removed. She then underwent diagnostic laparoscopy with disconnection of the fistulous tract and suturing of the fistulous opening on the sleeve [Figure 4b]. Simultaneous Roux-en-Y bypass was performed after creating a pouch by dividing the sleeve across for decompression to augment healing [Figures 4c and d]. She had an uneventful postoperative course and was discharged in 5 days. The patient was diagnosed 7 months postoperatively with a gastric sleeve leak and the time from diagnosis to fistula closure was 2 months.

Figure 4.

(a) Coronal section of contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan showing a sub-diaphragmatic collection with leak of oral contrast within draining to a bronchus in the left postero-basal segment on contrast study (b) Intraoperative photograph showing sutured repair of the fistula site (c and d) Intraoperative photograph showing creation of a gastric pouch by dividing the sleeve across and conversion to a Roux-en-Y bypass

Summary of results

To summarise, among 650 patients who underwent LSG from February 2008 to 2014, 3 (0.46%) developed a gastric leak. Two patients were referred with a gastric leak after LSG was performed at another institution. These patients comprised three females and two males, with a mean age of 45.60 ± 15.43 years (range 18 to 53) and mean BMI of 44.79 ± 5.35.

Patients with gastric leak presented with abdominal pain, fever, tachycardia, cough and pneumonia. Gastric leak was diagnosed at variable times ranging within 24 h to 7 months after surgery. One was an early leak (case 4), two were intermediate leaks (cases 1 and 2) and two were late leaks (cases 3 and 5). One patient had a type I gastric leak (case 5) and four patients had a type II gastric leak (cases 1, 2, 3 and 4). Patients with gastric leak were detected early with persistent tachycardia (case 4) or intermediate/late wherein they were well initially and then presented with fever, abdominal pain, cough and/or sepsis and were found to have sub-diaphragmatic collections/leaks (cases 1, 2, 3 and 5). The earliest symptom was tachycardia in patients with early leak, whereas fever was the earliest symptom in patients with intermediate/late leaks. There was no mortality in this series.

Intraoperative air leak tests were negative at the index surgery in the one early and one intermediate leak case (cases 3 and 4) but was useful in detecting the site of leak in the one patient with a late leak (case 5) operated at our institution. Postoperative contrast swallow tests with gastrografin on postoperative day 1 evidenced leak in only one patient with an early leak (case 4). Gastric leak was located at the proximal third of great curvature in all five patients and also in the mid-body in one patient (case 2), probably a complication of endoscopic dilatation of an early stricture at the incisura.

One type I early leak with a staple line bleed was explored within 48 h with evacuation of haematoma and underwent re-sleeve of proximal new greater curve with suture reinforcement (case 4). The other type I leak (late leak/chronic fistula) underwent suturing of the fistula site with conversion to Roux-en-Y bypass after a prior failed attempt of a 6-week stenting.

All type II leaks needed diagnostic lavage and drainage. Pigtail drainage was not considered suitable as an initial management due to the retro-gastric location of the abscess. One intermediate leak (type II leak) underwent fistula closure and simultaneous conversion to Roux-en-Y bypass with a Niti-S™ Beta™ oesophageal stent (Taewoong Medical, Seoul, Korea) over the sutured closure. One case of intermediate leak (type II leak) underwent stenting with a Niti-S™ Mega™ oesophageal stent (Taewoong Medical, Seoul, Korea), which was complicated by bleeding and needed removal. He then underwent surgery with only re-suturing at the fistula site, which failed. He recovered after prolonged conservative treatment. Lastly, one case of intermediate leak (type II leak) fistula underwent fistulo-jejunostomy for a mid-body fistula with distal stricture. She needed re-exploration for a missed proximal leak. At re-laparotomy, the site of leak was mobilised and excised with a linear stapler and the suture was reinforced and the loop fistulo-jejunostomy was also converted to a Roux-en-Y configuration. Nutrition was maintained by parenteral nutrition, feeding jejunostomy and nasojejunal tubes in four patients with early /intermediate leaks. In the patient with a chronic fistula, nutrition was maintained orally.

DISCUSSION

LSG is a popular restrictive bariatric procedure indicated as a standalone operation or as the first stage of the laparoscopic duodenal switch.[1,2,3] In this series, we analysed cases presenting with gastric leak among a consecutive series of 650 LSGs performed as a standalone operation at our institution over a 6-year period from 2008 to 2014. We found the incidence of gastric leak to be 0.46% at our institution (3 out of 650 sleeve gastrectomies). Our findings were consistent with reported incidences of gastric leaks, which have a variance of 0-4.3%.[10,11]

Clinical presentation of gastric leaks after surgery

Clinically the presentation in this series varied from leaks presenting early with sepsis, haemodynamic instability, and multiple organ failure to late presentations as peri-sleeve abscesses and chronic fistulas. This varied time and type of presentation were similar to that reported in the literature.[9,12] A majority of the leaks occurred after patient discharge. Hence, these clinical presentations should lead to a high index of suspicion and to an early workup to rule out leaks. If not recognised early and treated promptly, leaks can be a cause of prolonged morbidity as in the cases referred to us from outside and sometimes even mortality.

Detection of clinically suspected gastric leaks after surgery

A high clinical suspicion for a gastric leak should be immediately followed up with a CECT scan. As was our experience in two cases (cases 3 and 5), ultrasound imaging could not detect abnormalities perhaps because of obesity and the small size of walled-off collections with a sub-diaphragmatic, retro-gastric location. A CECT will differentiate localized leaks from diffuse spread and identify abscesses or fistulous tracts. As noted in this series, a leak of contrast material at CECT may or may not be identified. Absence of leak of contrast commonly occurs in early leaks probably because of temporary sealing off of the leak in the acute setting. This perhaps is the reason why gastrografin swallow tests performed in patients with a clinically suspected leak are commonly false negative.[13,14,15]

Endoscopy if performed early in the postoperative period should be done with minimal insufflation. A fistulous opening may be identified just beyond the oesophago-gastric junction. The site and size of the leak are noted and the suitability for stenting can be assessed if an oesophageal self-expanding metallic stenting is contemplated. A fistulous opening may not always be identified. At surgical re-exploration, an obvious fistulous opening may be identified. However, intraoperative identification and localisation of the site of leak may not be possible in some cases. We have noted that an air leak test, if performed, also could be negative. We do not know if the use of methylene blue might have been a better option as we do not routinely use this method. A methylene blue test may however, stain tissues and surrounding structures thereby making identification and re-suturing difficult. If the fistulous opening is identified endoscopically as suggested by Baltazar et al., a guidewire passed through the fistula tract preoperatively and left in place may help the surgeon find the defect on the gastric wall at re-exploration although we did not have any personal experience in this regard.[16] In some cases even when no fistulous opening is identified, the area along the staple line just beyond the oesophago-gastric junction should be re-sleeved or the suture reinforced (as in case 4) to avoid missed leaks, which in a majority of the cases are present just beyond the oesophago-gastric junction (as in cases 2 and 3).

Management options

The four key principles in managing a patient with a gastric leak are adequate drainage, closure of the fistula, decompression of the stomach and maintenance of nutrition.

Drainage of intra-abdominal collections

Adequate drainage together with broad-spectrum antibiotics is the first priority in the management of gastric leaks. If a drain is placed intra-operatively, it should be retained or if the leak occurred later in the course of management; patients may need immediate reoperation with peritoneal lavage and drainage. Image-guided pigtail drainage may not be a feasible option considering the location of the abscess as described previously.[15] Also, in our opinion as collections are peri-sleeve mostly retro-gastric, sub-diaphragmatic and loculated, surgical drainage may be the best option. Many series have however, reported the successful use of pigtail drainage in these patients considering it a good option in contained leaks.[17]

Surgical closure of the fistula

At re-exploration if contamination is localized, an attempt at closing the site of leak is performed if the local tissues are healthy.[9] If possible, re-sleeve of the fistula site by stapling can be performed with suture reinforcement. If this is not possible, the fistula site is directly sutured close. This is performed in those who have localized collections and in whom the tissues are healthy. Generalized peritonitis with haemodynamic instability is uncommon but if present, an immediate surgical repair of the fistula site may be deferred for later.

Surgical decompression of the stomach

Sleeves constitute areas of high pressure. Mean intra-gastric pressure when filled with saline was 43 ± 8 mmHg in a sleeved stomach versus 34 ± 6 mmHg in a normal stomach.[18] In our opinion, this high intra-gastric pressure is why sleeve leaks tend to be prolonged and sutured closures commonly fail. This is also the quoted as a reason why LSG has a higher leak rate than patients undergoing anastomotic techniques such as gastric bypass.[9] Although controversial, this is the reason why we recommend conversion of the sleeve into a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in addition to fistula repair to aid healing, as was performed in one patient with an acute and another with a chronic fistula (case 3 and 5). It has been suggested that a Roux limb allows better drainage than a sleeve, which can have possible functional disorders or stenotic areas.[16] This may not be advisable in the initial sitting if there is generalised peritonitis. In the patient with acute leak in this series, this was performed after a period of waiting after a laparoscopic drainage.

A fistula Roux may be performed in case of distal strictures wherein the edges of the gastric opening are freshened and widened and a side-to-side anastomosis is performed (case 2). A side-to-side anastomosis is preferred as rotation of the Roux-en-Y loop will be less likely.[16] However, this procedure was originally described as a successful option for any leak and may possibly be used instead of conversion of a sleeve into a Roux-en-Y bypass.[16] We do not recommend a fistula loop jujenostomy as it does not divert the bile flow and can make the fistula complex.

Endoscopic exclusion of the fistula

An oesophageal covered flexible self-expanding metallic stent (Beta stent) designed especially for sleeve leaks can be used to exclude the site of leak if it is small and present just beyond oesophago-gastric junction (case 3). Success rate of stenting is reported to be 50-84% in the treatment of acute leaks and chronic fistulas but with 60% chance of stent migration.[19] These stents can be used complementary to surgical fistula repairs as was done in the same patient in this series (case 3). Few series also report successful secondary closures with complementary use of stenting after surgical repair.[20]

The longer covered self-expanding metallic oesophageal stent also specifically designed for post-sleeve leaks (Mega stent) may also be used (cases 1 and 5). In this stent the upper side of the stent is located near the middle of the oesophagus, and the distal part of the stent is located in the antrum or in the first part of duodenum. As this stent is placed across the pylorus, it may also possibly play a role in decompression of the stomach at the same time. An advantage is that displacement of the stent is uncommon because of its length.[21] Another major advantage is that feeds can be continued orally and need not be interrupted. However, bleeding may be a possibility due to pressure as was seen in one patient in this series (case 2). We removed both types of stents uneventfully at 6-8 weeks.

Nutrition

Maintenance of nutrition is an important aspect that needs to be addressed in patients with sleeve leaks. In case oral feeding is restricted, nutrition is maintained by a feeding jejunostomy or naso-jejunal feeding or parenteral hyper-alimentation. In cases where a fully-covered, long, self-expanding metal stent (Mega stent) is used, oral intake can be continued as the long stent completely diverts entry into the stomach.

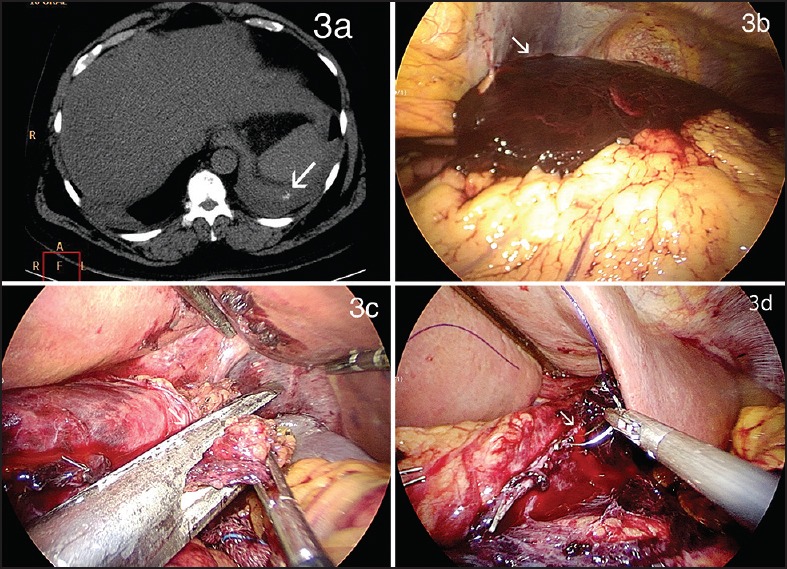

Sequence of procedures

A possible treatment algorithm is suggested in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Clinical algorithm for management of gastric sleeve leaks, *Fistula Roux-en-Y jujenostomy may be used if a distal stricture is suspected or instead of a Roux-en-Y bypass

In this series, use of surgical closure by suturing or stapling with decompression of the stomach and/or exclusion of the fistula by stenting does not completely lead to resolution of the leak but reduces the volume and reduces the time taken for closure of the fistula. The option of expectant management after only wide drainage is also a possibility but in our experience in two patients referred from outside hospitals, this usually leads to a prolonged course with high morbidity with non-healing probably related to the fact that the sleeve is a high pressure zone.

CONCLUSION

To summarise, clinical suspicion and CECT scan constitute the mainstay for the diagnosis of sleeve leaks. Leakage closure time may be shorter with early surgical and/or endoscopic intervention than expectant management. Sequence and choice of endoscopic oesophageal stenting and/or surgical re-intervention should be individualized according to clinical presentation. A combination of methods depending on the situation is often required to achieve success.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Deitel M, Crosby RD, Gagner M. The First International Consensus Summit for Sleeve Gastrectomy (SG), New York City, October 25-27, 2007. Obes Surg. 2008;18:487–96. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9471-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gagner M, Deitel M, Kalberer TL, Erickson AL, Crosby RD. The Second International Consensus Summit for Sleeve Gastrectomy, March 19-21, 2009. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2009;5:476–85. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deitel M, Gagner M, Erickson AL, Crosby RD. Third International Summit: Current status of sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7:749–59. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gagner M, Deitel M, Erickson AL, Crosby RD. Survey on laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) at the Fourth International Consensus Summit on Sleeve Gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2013;23:2013–7. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kehagias I, Karamanakos SN, Argentou M, Kalfarentzos F. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for the management of patients with BMI <50 kg/m 2. Obes Surg. 2011;21:1650–6. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0479-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Praveen Raj P, Senthilnathan P, Kumaravel R, Rajpandian S, Rajan PS, Anand Vijay N, et al. Concomitant laparoscopic ventral hernia mesh repair and bariatric surgery: A retrospective study from a tertiary care center. Obes Surg. 2012;22:685–9. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0614-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Csendes A, Díaz JC, Burdiles P, Braghetto I, Maluenda F, Nava O, et al. Classification and treatment of anastomotic leakage after extended total gastrectomy in gastric carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 1990;37(Suppl 2):174–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Csendes A, Burdiles P, Burgos AM, Maluenda F, Diaz JC. Conservative management of anastomotic leaks after 557 open gastric bypasses. Obes Surg. 2005;15:1252–6. doi: 10.1381/096089205774512410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burgos AM, Braghetto I, Csendes A, Maluenda F, Korn O, Yarmuch J, et al. Gastric leak after laparoscopic-sleeve gastrectomy for obesity. Obes Surg. 2009;19:1672–7. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9884-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bellanger DE, Greenway FL. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, 529 cases without a leak: Short-term results and technical considerations. Obes Surg. 2011;21:146–50. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0320-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daskalakis M, Berdan Y, Theodoridou S, Weigand G, Weiner RA. Impact of surgeon experience and buttress material on postoperative complications after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:88–97. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1136-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Márquez MF, Ayza MF, Lozano RB, Morales Mdel M, Díez JM, Poujoulet RB. Gastric leak after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2010;20:1306–11. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0219-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bekheit M, Katri KM, Nabil W, Sharaan MA, El Kayal ES. Earliest signs and management of leakage after bariatric surgeries: Single institute experience. Alex J Med. 2013;49:29–33. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee S, Carmody B, Wolfe L, Demaria E, Kellum JM, Sugerman H, et al. Effect of location and speed of diagnosis on anastomotic leak outcomes in 3828 gastric bypass cases. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:708–13. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marshall J, Srivastava A, Gupta SK, Rossi TR, DeBord JR. Roux-en-y gastric bypass leak complications. Arch Surg. 2003;138:520–4. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.5.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baltasar A, Serra C, Bengochea M, Bou R, Andreo L. Use of Roux limb as remedial surgery for sleeve gastrectomy fistulas. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:759–63. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casella G, Soricelli E, Rizzello M, Trentino P, Fiocca F, Fantini A, et al. Nonsurgical treatment of staple line leaks after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2009;19:821–6. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9840-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yehoshua RT, Eidelman LA, Stein M, Fichman S, Mazor A, Chen J, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy — volume and pressure assessment. Obes Surg. 2008;18:1083–8. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9576-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eubanks S, Edwards CA, Fearing NM, Ramaswamy A, de la Torre RA, Thaler KJ, et al. Use of endoscopic stents to treat anastomotic complications after bariatric surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:935–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisendrath P, Cremer M, Himpens J, Cadière GB, Le Moine O, Devière J. Endotherapy including temporary stenting of fistulas of the upper gastrointestinal tract after laparoscopic bariatric surgery. Endoscopy. 2007;39:625–30. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galloro G, Magno L, Musella M, Manta R, Zullo A, Forestieri P. A novel dedicated endoscopic stent for staple-line leaks after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: A case series. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:607–11. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2014.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]