Abstract

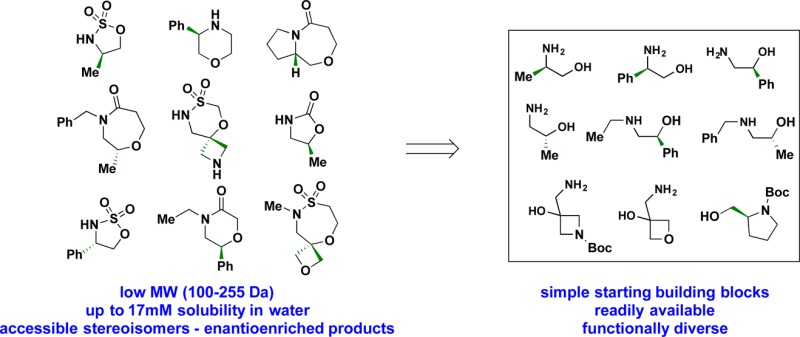

Efficient syntheses of chiral fragments derived from chiral amino alcohols are described. Several unique scaffolds were readily accessed in 1–5 synthetic steps leading to 45 chiral fragments, including oxazolidinones, morpholinones, lactams, and sultams. These fragments have molecular weights ranging from 100 to 255 Da and are soluble in water (0.085 to >15 mM).

Keywords: amino alcohols, fragment-based lead discovery, chiral fragments, drug discovery

Introduction

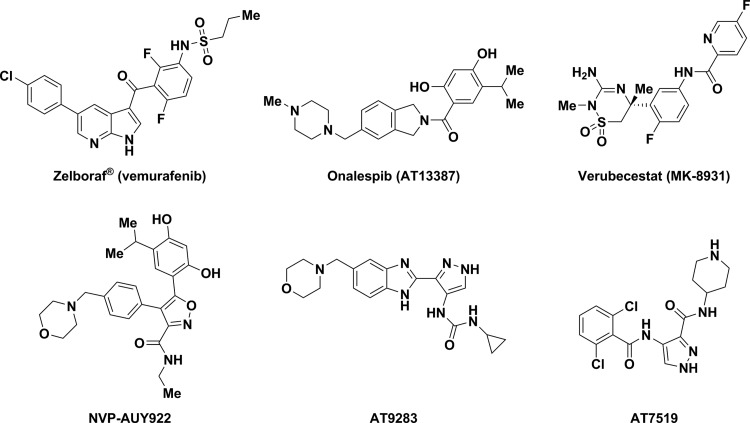

Fragment-based ligand discovery (FBLD) has emerged as a valuable complement to high-throughput screening over the past decade and has produced clinical-stage candidates (Figure 1), as well as the FDA-approved drugs vemurafenib and venetoclax.1−3 The rise of FBLD has been underpinned by methodological advances in the discovery of fragments hits by biophysical screening methods such as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), surface plasmon resonance (SPR), calorimetry, mass-spectrometry (MS) and X-ray crystallography. In contrast, the chemical features and optimal properties of fragments remain an area of debate and unresolved challenges.2 For instance, some fragments available from commercial vendors are limited by their poor solubility in water and lack of appropriate functionality for rapid fragment growth. Many commercial fragment collections are enriched in aromatic and heteroaromatic compounds, therefore expanding existing fragment chemical space by making compounds with a higher proportion of sp3-hybridized atoms may be beneficial.3,4 Here, we describe initial efforts to access sp3-rich chiral fragments from chiral amino alcohols, a class of starting materials advantaged by commercial availability, diversity of additional functional groups, and well-understood reactivity with electrophiles.

Figure 1.

Representative examples of clinical-stage and approved compounds originating from FBLD.

Results and Discussion

We synthesized low molecular weight 5-, 6- and 7-membered cyclic scaffolds from 1,2-amino alcohols and measured their aqueous solubilities to evaluate their potential for use in FBLD. Since thousands of enantioenriched 1,2-amino alcohols are already commercially available or easily obtained through modern asymmetric synthesis,5−9 chemical pathways and solubility data reported in this article will encourage the production of more diverse and larger sub-libraries.

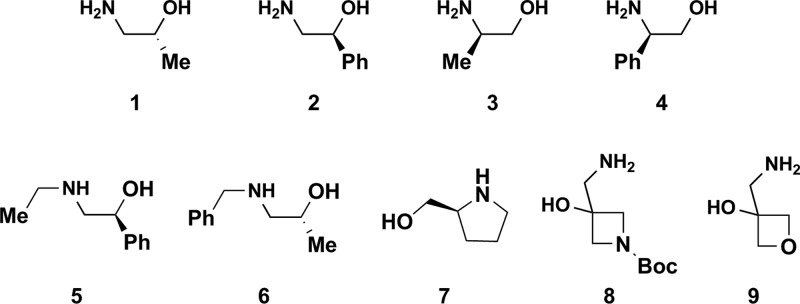

A representative selection of nine amino alcohols (Figure 2) were selected to pilot the synthesis of diverse skeletons. Amino alcohols 1-4 were chosen to explore the effects of both aliphatic and aromatic substituents on the carbon atom alpha to the amine or alcohol across all scaffolds. Amino alcohols 5-710 explore the role of secondary amines while 8 and 9(11) represent simple amino alcohols that can result in polar spirocyclic fragments with additional heteroatoms. The goal of this study was to “de-risk” the chemistry involved in accessing various scaffolds with a limited set of amino alcohols and to evaluate the suitability of the resulting fragments for FBLD by experimentally determining their aqueous solubilities.

Figure 2.

Structures of the representative chiral (or spiro) amino alcohol building blocks.

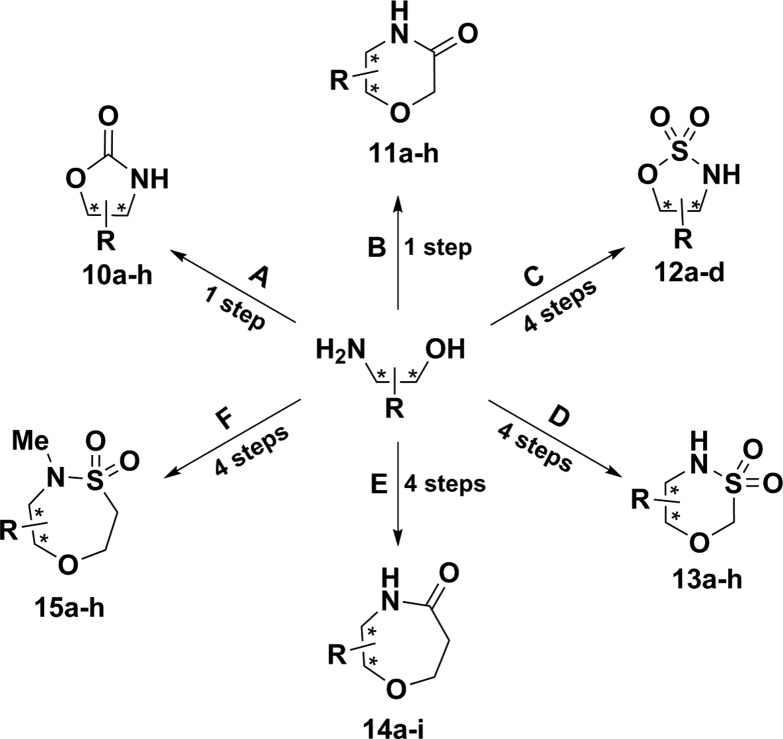

Oxazolidinones 10a–g (Scheme 1) were straightforward to prepare by previously reported approaches or modifications thereof.12−18 In general, amino alcohols could be treated with carbonyldiimidazole and triethylamine (Et3N), followed by heating at 60 °C overnight to afford the desired compounds in low to high yields (28–85%). Alternatively, oxazolidinones 10a and 10b were obtained in high yields (84%) by treatment of the neat amino alcohol with diethylcarbonate and a substoichiometric amount of sodium ethoxide at temperatures between 135 and 150 °C. Morpholinones 11a–f were synthesized by a similarly direct process in which the amino alcohols were treated with sodium hydride and ethyl chloroacetate at room temperature overnight to afford the morpholinone analogs in variable yields (19–82%).19 Morpholinones 11g and 11h were prepared using an alternative methodology in which the amino alcohols were treated with chloroacetyl chloride at room temperature, followed by intramolecular cyclization with sodium hydride at temperatures between 65 and 80 °C (18–22%).20 Conveniently, morpholinones 11c, 11d, 11f, and 11g, were transformed to morpholines 11i–l in low to good yields (23–75%) by direct reduction of the lactam with lithium aluminum hydride at room temperature (those not shown were not attempted or were readily commercially available).21,22

Scheme 1.

Reaction conditions: (A) CDI, Et3N, THF, 60 °C, 24 h, 27–85%; (B) NaH; ethyl chloroacetate, THF, rt, 24 h, 19–82%; (C) (i) Boc2O, Et3N, DCM, 0 °C, rt, 24 h, 83-99%; (ii) SOCl2, imidazole, Et3N, DCM, −40 °C, 2 h; then at rt for 2 h, 55–94%; (iii) RuCl3, NaIO4, MeCN:H2O (1:1), 0 °C to rt, 3 h, 31–95%; (iv) TFA, DCM, rt, 24 h, 66–90%; (D) (i) ClCH2SO2Cl, Et3N, DCM, 0 °C to rt, 6 h, 34-84%; (ii) PMB-Br, K2CO3, DMF, rt, 1 h, 17–89%; (iii) Cs2CO3, DMF, 80 °C, 24 h, 55–78%; (iv) CAN, MeCN:H2O (9:1), rt, 24 h, 24–78%; (E) (i) Boc2O, Et3N, DCM, 0 °C, rt, 24 h, 83–99%; (ii) t-butyl acrylate, Cs2CO3, t-BuOH, 24 h, 75–99%; (iii) 4.0 M HCl in dioxane, 24 h, 97–99%; (iv) T3P, Et3N, dioxane, 24 h, rt, 33–86%; (F) (i) TBS-Cl, Et3N, DCM, 0 °C to rt, 24 h, 71–95%; (ii) chloroethane sulfonyl chloride, Et3N, 0 °C to rt, 2 h, 75–95%; (iii) MeI, K2CO3, MeCN, 72 h, 70–90%; (iv) TBAF, THF, 2 h, 38–91%.

Sulfamidates 12a, 12b, and 12d were obtained by a four step sequence as outlined in Scheme 1.23,24 Protection of the amine as the t-butoxycarbonyl (Boc) carbamate and reaction with thionyl chloride in the presence of imidazole and triethylamine at −40 °C afforded the desired cyclic sulfamidite in modest to high yields (55–94%). The sulfamidite was subsequently oxidized using catalytic ruthenium(III) chloride and an excess of sodium periodate in acetonitrile to afford the protected sulfamidates. Removal of the Boc protecting group with trifluoroacetic acid afforded the desired sulfamidates (12a, 12b, and 12d) in good to high yields (66–90%). The N-benzylated sulfamidate 12c was prepared with an analogous approach in modest yields (40%) by treatment of the N-benzyl amino alcohol with thionyl chloride, imidazole, and triethylamine at –40 °C, followed by oxidation with catalytic ruthenium(III) chloride and sodium periodate in acetonitrile (products derived from amino alcohols 1, 2, 7, 8, and 5 were not investigated).

Our initial efforts to synthesize low molecular weight sultams commenced with the straightforward preparation of the α-chlorosulfonamide by treatment of amino alcohols with chloromethanesulfonyl chloride under basic conditions (20–84%). In accordance with previous observations on analogous systems by Borcard and colleagues,25 we observed that direct cyclization attempts from this intermediate were ineffective and resulted in poor conversion and polymeric products. These synthetic challenges were readily overcome by selective protection of the sulfonamide nitrogen with a p-methoxybenzyl (PMB) group (17–98%) and subsequent cyclization under basic conditions (55–87%). The PMB protecting group was readily removed by ceric ammonium nitrate (CAN) in a 9:1 mixture of acetonitrile and water to produce 13a-g in low to good yields (24–78%); 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-p-benzoquinone (DDQ) was wholly ineffective for this deprotection.

Limited literature precedent exists for the synthesis of 7-membered chiral lactams from amino alcohols.26 Treatment of amino alcohols with acryloyl chloride followed by intramolecular oxa-conjugate addition has been studied for accessing 7-membered lactams but this approach is plagued by ineffective cyclizations and poor yields.27,28 Here, we report an efficient route that furnishes the desired analogues, 14a–f, 14h, and 14i in four-steps. After N-Boc protection of the amino alcohols, treatment with t-butyl acrylate and cesium carbonate (Cs2CO3) in t-butanol (t-BuOH) at 50 °C yielded the desired conjugate addition products in good to high yields (75–99%). Next, a global deprotection was performed using hydrochloric acid (HCl) in dioxane to afford the amine hydrochloride salts in high yields yields (97–100%). The intermediate salts were surveyed for optimal intramolecular amidation conditions which were achieved upon treatment with propylphosphonic anhydride (T3P) in dioxane and stirring at room temperature for 24 h. As such, analogs 14a–f, 14h, and 14i were prepared in modest to high yields (33–83%). Compared to existing methods for accessing these 7-membered rings that require high heat and pressure,29 the T3P-mediated cyclization reported here proceeds at ambient conditions and hence represents an advance. Given the mild conditions, we anticipate broader substrate scope for the T3P-mediated access to 7-membered ring lactams.

The 7-membered sultams (Scheme 1, 15a–h) were synthesized by a modified protocol in accord with the precedent of Zhou and colleagues.30,31 After protection of the alcohol as the t-butyldimethylsilyl (TBS) ether, treatment with 2-chloroethanesulfonyl chloride in the presence of excess Et3N yielded the vinyl sulfonamide intermediates in good to high yields (60–98%). In order to promote intramolecular cyclization, all secondary vinyl sulfonamides were methylated to afford N-Me-sulfonamides (70-90%). Lastly, intramolecular cyclizations were achieved in a one-pot fashion via tetra-n-butylammonium fluoride (TBAF) promoted TBS cleavage, followed by hetero-conjugate addition to afford the desired sultams 15a–h in low to high yields (37–97%). No reaction was observed with secondary sulfonamides. We postulate the favorable s-trans conformation of the secondary sulfonamides hinders the cyclization reaction.

Overall, we prepared a library of 50 (Figure 3, Schemes 1 and 2) chiral amino alcohol-derived fragments using the methodologies described above and amino alcohols chosen from the set shown in Figure 1. All of the prepared compounds were evaluated in an aqueous solubility assay using either LC-MS/MS or UV for quantification.32 As displayed in Figure 3 and Scheme 2, the aqueous solubilities ranged from 0.085 to >15 mM.

Figure 3.

Readily prepared pilot collection of 45 chiral amino alcohol-derived fragments presented with overall yields and solubility data (nd = not determined). Compounds with >0.50 mM solubilities were exposed to an assay with a 0.50 mM upper limit (see Supporting Information). (a) Amino alcohol 7 was explored solely for the 7-membered lactam family of compounds.

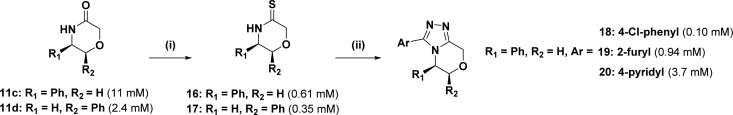

Scheme 2. Synthetic Route to Expanded Product Library Derived from 11c as a Representative Example.

Reaction conditions: (i) Lawesson’s reagent, THF, 55 °C, 3 h, 78%; (ii) RCONHNH2, t-BuOH, 135 °C, 24 h, 39-63%. Aqueous solubility data is show in parentheses.

We then investigated the utility of our chiral fragments as starting points for further diversification. For example, compound 11c was transformed into an array of extended triazole products via thiolactam intermediates (Scheme 2). Following a modified procedure from Wishka and Walker,33 two thiolactams 16 and 17 were obtained in 78 and 48% yield, respectively, upon treatment with Lawesson’s reagent. Conversion of 16 into triazoles 18–20 was accomplished by heating in an excess of the appropriate hydrazide in t-BuOH for 24 h (39-63%).34

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have developed facile and convenient synthetic routes to several families of unique and water-soluble amino alcohol-derived chiral fragments. A total of 45 compounds including chiral morpholines, lactams, sultams, and sulfamidates were synthesized in 1-5 synthetic steps. These chiral fragments are characterized by low molecular weights (100–255 Da) and aqueous solubilities in the range of 0.085 to >15 mM which are important criteria among compounds useful for FBLD.35

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for contributions from Ursula Krenz and her team (Bayer) for solubility measurements; Ursula Ganzer and Jürgen Scholz (Bayer) for solubility assay optimization and measurements; the Broad Institute Compound Management team for curating the synthesized compounds; and Dr. Stephen Johnston (Broad) for solubility measurements and analytical chemistry support.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acscombsci.6b00050.

Information on compound synthesis, characterization, detailed results, experimental procedures, and spectra (PDF)

Author Present Address

∇ S.H.: GlaxoSmithKline, 7333 Mississauga Road, Mississauga, Ontario, L5N 6L4, Canada

Author Present Address

¶ A.J.P.: C4 Therapeutics, Inc., 675 West Kendall Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02142, United States

Author Contributions

S.H. and S.D.N. contributed equally. The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors.

Support of this research was provided by the NIGMS (GM038627), NSERC Canada (postdoctoral fellowship awarded to S.H), and Bayer Pharma AG. S.L.S. is an Investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) and Ž.V.B. is an HHMI Postdoctoral Associate. S.D.N. is funded in part by Harvard University’s Graduate Prize Fellowship. S.F.L., A.G., J.S., and C.B. were funded by the HHMI Exceptional Research Opportunities Program (EXROP). D.C. was funded by Summer Research Opportunities at Harvard (SROH).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Joseph-McCarthy D.; Campbell A. J.; Kern G.; Moustakas D. Fragment-based lead discovery and design. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014, 54, 693–704. 10.1021/ci400731w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Murray C. W.; Rees D. C. The rise of fragment-based drug discover. Nat. Chem. 2009, 1, 187–192. 10.1038/nchem.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Baker M. Fragment-based lead discovery grows up. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2013, 12, 5–7. 10.1038/nrd3926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Souers A. J.; Leverson J. D.; Boghaert E. R.; Ackler S. L.; Catron N. D.; Chen J.; Dayton B. D.; Ding H.; Enschede S. H.; Fairbrother W. J.; Huang D. C. S.; Hymowitz S. G.; Jin S.; Khaw S. L.; Kovar P. J.; Lam L. T.; Lee J.; Maecker H. L.; Marsh K. C.; Mason K. D.; Mitten M. J.; Nimmer P. M.; Oleksijew A.; Park C. H.; Park C.-M.; Phillips D. C.; Roberts A. W.; Sampath D.; Seymour J. F.; Smith M. L.; Sullivan G. M.; Tahir S. K.; Tse C.; Wendt M. D.; Xiao Y.; Xue J. C.; Zhang H.; Humerickhouse R. A.; Rosenberg S. H.; Elmore S. W. ABT-199, a potent and selective BCL-2 inhibitor, achieves antitumor activity while sparing platelets. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 202–208. 10.1038/nm.3048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Hennessy E. J. Selective inhibitors of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL: Balancing antitumor activity with on-target toxicity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 2105–2114. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlanson D. Fragment-based lead discovery: a chemical update. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2006, 17, 643–652. 10.1016/j.copbio.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod M. C.; Singh G.; Plampin J. N. III; Rane D.; Wang J. L.; Day V. W.; Aubé J. Probing chemical space with alkaloid-inspired libraries. Nat. Chem. 2014, 6, 133–140. 10.1038/nchem.1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Larrow J. F.; Schaus S. E.; Jacobsen E. N. Kinetic Resolution of Terminal Epoxides via Highly Regioselective and Enantioselective Ring Opening with TMSN3. An Efficient, Catalytic Route to 1,2-Amino Alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 7420–7421. 10.1021/ja961708+. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Kumar M.; Kureshy R. I.; Saravanan S.; Verma S.; Jakhar A.; Khan N. H.; Abdi S. H. R.; Bajaj H. C. Unravelling a New Class of Chiral Organocatalyst for Asymmetric Ring-Opening Reaction of Meso Epoxides with Anilines. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 2798–2801. 10.1021/ol500699c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trost B. M.; Terrell L. R. A Direct Catalytic Asymmetric Mannich-type Reaction to syn-Amino Alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 338–339. 10.1021/ja028782e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeza A.; Casas J.; Nájera C.; Sansano J. M.; Saá J. M. Enantioselective Synthesis of Cyanohydrin O-Phosphates Mediated by the Bifunctional Catalyst Binolam–AlCl. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 3143–3146. 10.1002/anie.200351552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Fraunhoffer K. J.; White M. C. syn-1,2-Amino Alcohols via Diastereoselective Allylic C-H Amination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 7274–7276. 10.1021/ja071905g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Covell D. J.; White M. C. A Chiral Lewis Acid Strategy for Enantioselective Allyl C-H Oxidation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 6448–6451. 10.1002/anie.200802106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramasastry S. S. V.; Zhang H.; Tanaka F.; Barbas C. F. III. Direct Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of anti-1,2-Amino Alcohols and syn-1,2-Diols through Organocatalytic anti-Mannich and syn-Aldol Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 288–289. 10.1021/ja0677012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuitschik G.; Rogers-Evans M.; Müller K.; Fischer H.; Wagner B.; Schuler F.; Polonchuk L.; Carreira E. M. Oxetanes as Promising Modules in Drug Discovery. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 7736–7739. 10.1002/anie.200602343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mickelson J. W.; Belonga K. L.; Jacobsen E. J. Asymmetric Synthesis of 2,6-Methylated Piperazines. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 4177–4183. 10.1021/jo00118a039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adam W.; Bosio S. G.; Turro N. J. Highly diastereoselective dioxetane formation in the photooxygenation of enecarbamates with an oxazolidinone chiral auxiliary: steric control in the [2 + 2] cycloaddition of singlet oxygen through conformational alignment. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 8814–8815. 10.1021/ja026815k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paz J.; Pérez-Balado C.; Iglesias B.; Muñoz L. Carbon dioxide as a carbonylating agent in the synthesis of 2-oxazolidinones, 2-oxazinones, and cyclic ureas: scope and limitations. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 3037–3046. 10.1021/jo100268n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espino C.G.; Du Bois J. A Rh-catalyzed C-H insertion reaction for the oxidative conversion of carbamates to oxazolidinones. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 598–600. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allali H.; Tabti B.; Alexandre C.; Huet F. An easy route to 4-substituted 2-oxazolidinones from prochiral-1,3-diols. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2004, 15, 1331–1333. 10.1016/j.tetasy.2004.02.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoli G.; Bosco M.; Carlone A.; Locatelli M.; Melchiorre P.; Sambri L. Direct catalytic synthesis of enantiopure 5-substituted oxazolidinones from racemic terminal epoxides. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 1983–1985. 10.1021/ol050675c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka T.; Kondoh A.; Terada M. Kinetic resolution of racemic amino alcohols through intermolecular acetalization catalyzed by a chiral brønsted acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 1048–1051. 10.1021/ja512238n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Delft F.L.; Timmers C. M.; Van der Marel G. A.; van Boom J. H. Preparation of 2-oxazolidinones by intramolecular nucleophilic substitution. Synthesis 1997, 4, 450–454. 10.1055/s-1997-1198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Norman B. H.; Kroin J. S. Alkylation Studies of N-Protected-5-substituted Morpholin-3-ones. A Stereoselective Approach to Novel Methylene Ether Dipeptide Isosteres. J. Org. Chem. 1996, 61, 4990–4998. 10.1021/jo960496w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Brenner E.; Baldwin R. M.; Tamagnan G. Asymmetric Synthesis of (+)-(S,S)-Reboxetine via a New (S)-2-(Hydroxymethyl)morpholine Preparation. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 937–939. 10.1021/ol050059g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Angell R.; Fengler-Veith M.; Finch H.; Harwood L. M.; Tucker T. T. Cycloadditions of 1,3-oxazolium-4-olates (isomünchnones) by rhodium(II)-induced decomposition of α-diazocarbonyl derivatives of (5R)- and (5S)-phenyloxazin-3-one as a chiral template. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 4517–4520. 10.1016/S0040-4039(97)00918-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Alexander R.; Balasundaram A.; Batchelor M.; Brookings D.; Crépy K.; Crabbe T.; Deltent M.-F.; Driessens F.; Gill A.; Harris S.; Hutchinson G.; Kulisa C.; Merriman M.; Mistry P.; Parton T.; Turner J.; Whitcombe I.; Wright S. 4-(1,3-Thiazol-2-yl)morpholine derivatives as inhibitors of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 4316–4320. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.06.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Dugar S.; Sharma A.; Kuila B.; Mahajan D.; Dwivedi S.; Tripathi V. A concise and efficient synthesis of substituted morpholines. Synthesis 2015, 47, 712–720. 10.1055/s-0034-1379641. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bettoni G.; Franchini C.; Tortorella V.; et al. Synthesis and Absolute Configuration of Substituted Morpholines. Tetrahedron 1980, 36, 409–415. 10.1016/0040-4020(80)87009-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kashima C.; Harada K. Synthesis and reaction of optically active morpholinones. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1988, 6, 1521–1526. 10.1039/p19880001521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S.; Han J.; Lee E.S.; Choi E. B.; Lee H. K. Enantioselective synthesis of cyclic sulfamidates by using chiral rhodium-catalyzed asymmetric transfer hydrogenation. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 4184–4187. 10.1021/ol1017905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Mansueto M.; Frey W.; Laschat S. Ionic liquid crystals derived from amino acids. Chem. - Eur. J. 2013, 19, 16058–16065. 10.1002/chem.201302319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kim S. J.; Jung M.-H.; Yoo K. H.; Cho J.-H.; Oh C.-H. Synthesis and antibacterial activities of novel oxazolidinones having cyclic sulfonamide moieties. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 5815–5818. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Zhang L.; Luo S.; Mi X.; Liu S.; Qiao Y.; Xu H.; Cheng J.-P. Combinatorial synthesis of functionalized chiral and doubly chiral ionic liquids and their applications as asymmetric covalent/non-covalent bifunctional organocatalysts. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008, 6, 567–576. 10.1039/B713843A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borcard F.; Baud M.; Bello C.; Dal Bello G.; Grossi F.; Pronzato P.; Cea M.; Nencioni A.; Vogel P. Synthesis of new oxathiazinane dioxides and their in vitro cancer cell growth inhibitory activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 5353–5356. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uesugi S.; Li Z.; Yazaki R.; Ohshima T. Chemoselective catalytic conjugate addition of alcohols over amines. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 1611–1615. 10.1002/anie.201309755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGhee A.M.; Kizirian J. C.; Procter D. J. Synthesis and evaluation of a new polymer-supported pseudoephedrine auxiliary for asymmetric alkylations on solid phase. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007, 5, 1021–1024. 10.1039/b700477j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F.; Yang H.; Fu H.; Pei Z. Efficient copper-catalyzed Michael addition of acrylic derivatives with primary alcohols in the presence of base. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 517–519. 10.1039/C2CC37595H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankaran K.; Donnelly K. L.; Shah S. K.; Caldwell C. G.; Chen P.; Hagmann W. K.; MacCoss M.; Humes J. L.; Pacholok S. G.; Kelly T. M.; Grant S. K.; Wong K. K. Synthesis of analogs of (1,4)-3- and 5-imino oxazepane, thiazepane, and diazepane as inhibitors of nitric oxide synthases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004, 14, 5907–5911. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Tong K.; Tu J.; Qi X.; Wang M.; Fu H.; Pittman C. U. Jr.; Zhou A.; et al. Syntheses of five- and seven-membered ring sultam derivatives by Michael addition and Baylis–Hillman reactions. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 2369–2375. 10.1016/j.tet.2012.12.083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Zhou A.; Rayabarapu D.; Hanson P. R. Click, Click, Cyclize”: A DOS Approach to Sultams Utilizing Vinyl Sulfonamide Linchpins. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 531–534. 10.1021/ol802467f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Zhou A.; Hanson P. R. Synthesis of sultam scaffolds via intramolecular oxa-Michael and diastereoselective Baylis-Hillman reactions. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 2951–2954. 10.1021/ol8009072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M.; Wang Y.; Qi X.; Xia G.; Tong K.; Tu J.; Pittman C. U. Jr.; Zhou A. Selective Synthesis of Seven- and Eight-Membered Ring Sultams via Two Tandem Reaction Protocols from One Starting Material. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 3700–3703. 10.1021/ol301535j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi T. C. K. Phase solubility techniques. Adv. Anal. Chem. Instr. 1965, 4, 117–212. [Google Scholar]

- Wishka D. G.; Walker D. P. Synthesis of (±)-6-oxa-3-azabicyclo[3.1.1]heptan-2-thione: A potential synthon for the preparation of novel heteroaryl-annulated bicyclic morpholines. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 4713–4715. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.07.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shridhar D. R.; Jogibhukta M.; Vishwakarma L. C.; Joshi P. P.; Narayan G. K. A. S. S.; Singh P. P.; Seshagiri Rao C.; Junnarkar A. V. Synthesis and biological activity of some substituted 4H-[1,2,4]triazolo[3,4-c][1,4]benzoxazines and 4H-[1,2,4]triazolo[3,4-c][1,4]benzothiazines. Indian J. Chem. 1984, 23B, 445–448. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer M.; Ichihara O.; Kirchhoff C.; Schade M.; Whittaker M.. Assembling a Fragment Library. In Fragment-Based Drug Discovery: A Practical Approach; Zartler E. R., Shapiro M. J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: West Sussex, U.K., 2008; pp 52–53. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.