Abstract

The vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) is the main nerve of the parasympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system. Vagal paragangliomas (VPGLs) are a prime example of an endocrine tumor associated with the vagus nerve. This rare, neural-crest tumor constitutes the second most common site of hereditary head and neck paragangliomas (HNPGLs), most often in relation to mutations in the succinate dehydrogenase subunit D (SDHD) gene. The treatment paradigm for VPGL has progressively shifted from surgery to abstention or therapeutic radiation with curative-like outcomes. Parathyroid tissue and parathyroid adenoma can also be found in close association with the vagus nerve in intra or paravagal situations. Vagal parathyroid adenoma can be identified with preoperative imaging or suspected intraoperatively by experienced surgeons. Vagal parathyroid adenomas located in the neck or superior mediastinum can be removed via initial cervicotomy, while those located in the aorto-pulmonary window require a thoracic approach. This review particularly emphasizes the embryology, molecular genetics, and modern imaging of these tumors.

Key Terms: vagus nerve, paragangliomas, hyperparathyroidism, diagnostic imaging

Vagusnerve

The vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) is the main nerve of the parasympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system. It originates from the medulla oblongata and exits the skull-base via the jugular foramen (pars vascularis). The vagus nerve descends vertically through the neck within the the carotid sheath (Figure 1) and into the mediastinum with different paths on the left and right sides. Among the different branches that innervate the laryngeal and pharyngeal muscles, the recurrent laryngeal nerves (RLNs) are of major clinical importance.

Figure 1. Usual head and neck course of vagus nerve drawn on a cross sectional CT scanner with contrast injection.

Vagus nerve (red spot) enters the lateral skull base in pars vascularis of jugular foramen (a) and the descends in the neck in the anterior angle formed by the posterolateral common carotid artery (CCA, white arrow) and posteromedial internal jugular vein (IJV, *) walls (b–e). In the upper thorax (f), vagal nerve is located anteriorly to sub-clavian artery (arrow heads).

The vagus nerve contains sensory (80–90%) and motor fibers and serves as the communication pathway between the central nervous system (CNS) (hypothalamus and its connections) and the viscera. The parasympathetic system regulates “rest and digestive” functions. Afferent signaling via the vagus nerve transmits visceral stimuli (taste buds, heart, lungs, and other visceral organs) to the nucleus of the solitary tract. The cell bodies of these fibers are located in the inferior ganglion (nodose ganglion) of the vagus nerve. Somatic sensory fibers arising from the external ear have their cell bodies in the superior (jugular) ganglion and then project to the trigeminal nucleus (Baker 2005). Vagus motor fibers arising from the dorsal motor nucleus innervate visceral organs (heart, digestive system), and those from the nucleus ambiguous are involved in speech and swallowing.

From an embryology standpoint, preganglionic motor and somatic sensory neurons, as well as supporting cells of the cranial ganglia, arise from neural crest cells. By contrast, the visceral sensory innervation from the vagus nerve arises from the third epibranchial placode (nodose placode) (Baker 2005).

Vagalp aragangliomas

Tumor origin and molecular genetics

Vagus nerve paraganglia belong to the family of parasympathetic paraganglia. Members act as chemoreceptors and are involved in the visceral reflex circuits. Vagus paraganglia derived from the neural crest are constituted by 6 to 7 small collections of paraganglionic tissue mainly located at or just below the nodose ganglion (inferior ganglion vagus nerve). It can also be found at the level of the carotid bifurcation or along the vagus nerve in the mediastinum. Vagus paraganglia is morphologically identical to the carotid body with glomus cells (type I) and located within the nerve or adjacent to the nerve (juxta-vagus). Although the role of vagus paraganglia is currently largely unknown, it may acts as an immunosensory receptor and participate in a neural reflex mechanism during sepsis or injury.

Paragangliomas (PGLs) can arise from all parasympathetic paraganglia sites. They can occur as sporadic or hereditary tumors, with the latter accounting for at least 40% of cases. Of all known genetic mutations, those in the succinate dehydrogenase (SDHx) subunit D (SDHD) gene are currently the leading cause of hereditary head and neck PGLs (HNPGLs) (>50%), followed by SDHB (20%) and SDHC mutations (Baysal, et al. 2002; Neumann, et al. 2009; Piccini, et al. 2012). The inheritance pattern of the SDHB and SDHC genes is autosomal dominant, whereas for SDHD, the disease almost always occurs when the mutations are inherited from the father, a mode of inheritance consistent with maternal imprinting (Baysal 2013). Other pheochromocytoma/PGL predisposing genes are rarely involved in the development of HNPGLs. The vagus PGL (VPGL) arises from paraganglionic tissue associated with the vagus nerve. They represent 13% of sporadic HNPGLs (Erickson, et al. 2001) and represent the second most common site (31%) of hereditary HNPGLs after jugular PGL (Gimenez-Roqueplo, et al. 2013). VPGLs can be confined to the upper cervical region in the retrostyloid parapharyngeal space, abutting against the jugular foramen and the skull base with either anterior displacement and/or encasement of the internal carotid artery and extend into the jugular foramen, often with intracranial extension.

Genetic and clinical characteristics of non-syndromic PPGL associated with mutations in the SDH genes (PGL syndromes 1–5) are detailed in Table 1 (Benn, et al. 2015).

Table 1.

Clinical features of PGL syndromes 1–5

| Gene | Syndrome | Inherance | HNPGL | Thoracic or retroperitoneal PGL | PHEO | Multifocality | Malignancy risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDHA | PGL5 | Autosomal dominant | Rare | Rare | Rare | Rare | Rare |

| SDHB | PGL4 | Autosomal dominant | 20–30% | 50% | 20–25% | 30% | 30–40% |

| SDHC | PGL3 | Autosomal dominant | 90% | 10% (mediastinum) | Rare | 20% | Very rare |

| SDHD | PGL1 | Autosomal dominant (paternal transmission) | 85% | 20–25% | 10–25% | 50–60% | 3–10% |

| SDHAF2 | PGL2 | Autosomal dominant (paternal transmission) | 100% | 0% | 0% | 90% | None reported |

Adapted from Benn, et al.

Diagnosis and imaging

VPGLs can be associated with subtle signs like pharyngeal discomfort or foreign body sensation, but in many cases, tumors are incidentally discovered and diagnosed in SDHx-mutation carriers. Otologic symptoms may also occur in cases of eustachian tube orifice obstruction. Patients with a suspected VPGL require measurement of plasma metanephrines, methoxytyramine, and plasma chromogranin A, but these markers are often normal. VPGLs are typically found in the parapharyngeal retrostyloid (post-styloid or carotid artery) space. There are many potential differential diagnoses of VPGL: neurogenic tumors (schwannoma, neurofibroma), lymph node metastasis (nasopharynx/oropharynx, thyroid cancer, melanoma); lymphoma; other primary tumors (meningioma, ganglioneuroma, haemangiopericytoma, cavernous hemangioma, sarcoma), and a variety of uncommon lesions (i.e., abcess, internal carotid artery aneurysm, internal jugular vein thrombosis, vascular malposition, or hematoma). Specific data about the relative frequency for various causes of parapharyngeal retrostyloid masses are lacking. Based on our longstanding experience in otolaryngology imaging and case report series, the four main causes of parapharyngeal retrostyloid masses are lymph nodes (approximately 80%), schwannoma (5%), paraganglioma (5%) and neurofibroma (3%) (Kuet, et al. 2015; Pang, et al. 2002). Other causes account for the remaining 7%.

The role of imaging is multiple: diagnosis of PGL, staging according to Netterville’s classification, detection of multifocality, and assessment for potential metastases (2). Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the cornerstones of initial evaluation. VPGLs, like other HNPGLs, usually demonstrate marked enhancement of intra-tumoral vessels following contrast administration on CT. On MRI, VPGLs appear as a non-specific intermediate signal lesion on T1-weighted images, and as a non-specific intermediate-to-high signal on T2-weighted MRI images. Intense enhancement after gadolinium injection is common. Flow signal voids in the tumor is typical of PGLs, with a “salt and pepper” appearance on spin-echo sequences. These flow-voids correspond to intra-tumoral arterial vessels on MR angiography (Arnold, et al. 2003; Johnson 1998; Neves, et al. 2008; van den Berg 2005; van den Berg, et al. 2004). These arterial feeders can be imaged with MR angiography sequences either with (time resolved gadolinium MRA) or without gadolinium injection on TOF sequences (time-of-flight MRA) (Figure 2). These sequences have been shown to be highly informative, with sensitivities and specificities of 90% and 94% (van den Berg et al. 2004) and 100% and 94% (Neves et al. 2008), respectively. Three dimensional MRA sequences (3D TOF MR and 3D time resolved angiography) are more sensitive than conventional 2D sequences, especially in detecting smaller PGLs that can be observed in SDHx mutation carriers (Arnold et al. 2003). Fusion images between 3D co-registrated 3D MR angiography to anatomical data (3D gradient-echo T1-weighted VIBE fat-saturated sequence) are particularly informative. Perfusion MR and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), which depend on capillary membrane permeability and tissue cellularity, respectively, are still under evaluation in this indication (Dong and Liu 2012).

Figure 2. Typical appearance of a VPGL on MRI.

A: SE T1wi, B: SE T2wi, C: 3D Vibe T1wi with gadolinium and fat suppression, D: early arterial phase of a 2D T1 DCE) and 18F-FDOPA (E: PET/CT, F: PET). The VPGL is located in the left post-styloïd para-pharyngeal space (carotid space), splaying ICA (arrow head) and IJV (arrow).

A head-to-head comparison between somatostatin analogs (SSA) labelled with gallium-68 (68Ga-DOTA-SSA) and 18F-fluorodopa (18F-FDOPA) PET has been performed in only 5 studies: one retrospective study from Innsbruck Medical University (68Ga-DOTATOC in 20 patients with unknown genetic background) (Kroiss, et al. 2013), 3 prospective studies from the National Institutes of Health (SDHB, HNPGL, and sporadic, metastatic) (68Ga-DOTATATE in 17 and 20 patients) (Janssen, et al. 2015; Janssen, et al. 2016a; Janssen, et al. 2016b), and one prospective study from La Timone University Hospital (68Ga-DOTATATE in 30 patients). In these studies, 68Ga-DOTA-SSA PET/CT detected more primary HNPGLs, as well as SDHx-associated-PGLs than 18F-FDOPA PET/CT (Archier, et al. 2016) (Figure 3). This radiopharmaceutical should be considered as the first-line imaging modality for HNPGLs. A distinction between VPGL, carotid body PGL (CBP), and exceptional cases of sympathetic PGL could be difficult. At the level of the carotid bifurcation, the distinction between VP and CBP is based on the displacement of the internal and external carotid artery. VPs tend to displace both vessels together rather than splaying them as in CBP (“Lyre sign”). This distinction is difficult to ascertain on an unenhanced PET/CT. A thin nipple at the top of the VP, which corresponds to a protrusion of paraganglionic cells within the nerve, can be observed in large tumors.

Figure 3. Multifocal SDHD-related VPGL.

Comparative cross sectional imaging centered on bilateral VPGL: 68Ga-DOTATATE (A, B), SE T2 wi (C), 3D gradient echo T1 wi with fat saturation (VIBE) after injection of gadolinium (D), Time of flight (TOF) MRA without gadolinium injection (E), early arterial phase of a 4D MRA with gadolinium injection. This case shows that VPGL (white arrows) were easily detected on 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT On MR, VPGL were not detected on conventional 2D T2, and hardly distinguishable on 3D T1 with gadolinium injection. AngioMR sequences confirm hyper-vascular pattern demonstrating high velocity arterial feeders on TOF (E) and early enhancement on 4D MRA with gadolinium injection. Note that on morphological data, these 2 mm VPGL were more easily detected on TOF sequence without injection. (Vessels are marked by a colour arrow, red: internal carotid artery, blue: internal jugular vein).

Proper diagnosis (Figure 4), staging and early detection of metastatic disease is a key point for choosing the optimal treatment and follow-up plan, as well as insuring the best patient outcome. CT, whole-body MRI, and PET imaging provide the most useful complementary information. 68Ga-DOTA-SSA PET/CT seems to have an excellent sensitivity, regardless of genetic background (Janssen et al. 2015; Janssen et al. 2016a). If 68Ga-DOTA-SSA is not available, 18F-FDOPA PET may be the imaging modality of choice in the absence of a SDHB mutation, or even when the genetic status is unknown (Figure 5). By contrast, 18F-FDG PET should be considered as the first alternative imaging for SDHx-related cases.

Figure 4. Sporadic VPGL.

68Ga-DOTATATE (A, B), curved planar reconstructions of a 3D-GRE T1 Vibe with gadolinium and fat suppression (C) and 3D-SE (Space) T2 wi. An avid 68Ga-DOTATATE VPGL (*) is located at the level of mandibular angle. Adjacent to the VGPL 3D MRI demonstrates in this case the vagus nerve involvement due to its abnormal thickening. Abnormal thickening of the nerve is seen from lesion to the skull base (pars vascularis of jugular foramen) and may be due to vasa nervorum arterial feeders and edema more than peri-neural spread.

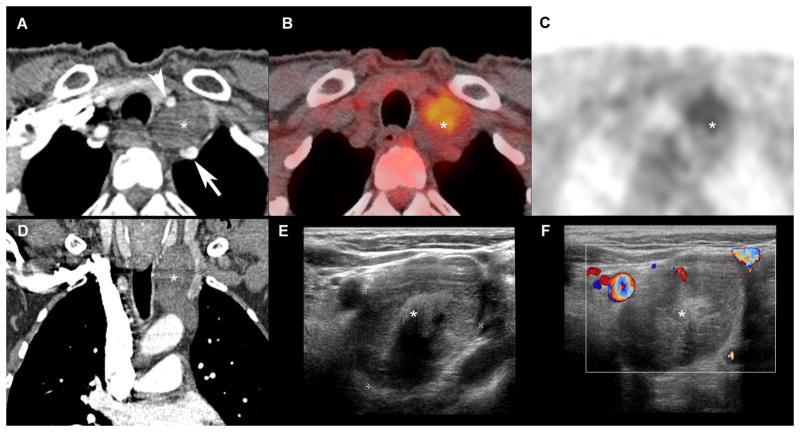

Figure 5. Schwannoma of the vagus nerve.

Comparative cross sectional imaging: CT-scanner, arterial phase (A, D), 18FDG-PET (B, C), 2D ultrasound (E), 2D US with doppler (F). Multimodal assessment demonstrates a well-defined margin lesion (*) in cervico-thoracic region, located in the vagus nerve pathway, splaying right primitive carotid artery (arrow head) and right sub-clavian artery (arrow). This lesion does not enhance at the arterial phase CT (A, D), nor demonstrates hyper-vascularity at Doppler.

Treatment

Treatment of VPGLs is challenging for a number of reasons. Although these tumors are generally benign, there may be a mass effect or invasion of surrounding critical and delicate structures, invasion of the skull base, and extension intracranially. VPGLs have an intimate relationship to the other cranial nerves at the skull base and thus, may present in some patients as cranial nerve palsy. Additionally, VPGLs have a high propensity to be multicentric and bilateral, especially in hereditary forms (Table 1). The reported malignancy risks of HNPGLs usually ranges from 3 to 7%. VPGL have a lower malignancy risk compared with their carotid counterparts. Tumors with gross tumor infiltration into surrounding structures and/or related to SDHx (B>D) mutations should be considered at a higher risk for malignancy, although properly designed studies have not been done (Boedeker, et al. 2007; Ellis, et al. 2013; van Hulsteijn, et al. 2012; Zheng, et al. 2012).

VPGLs can be resected via a transcervical approach. The risk for major vascular injury is smaller than in patients with carotid body PGLs. However, surgical resection of VPGLs almost always leads to the sacrifice of the vagus nerve, and sometimes palsy of other adjacent cranial nerves (Suarez, et al. 2013). Surgery of VPGLs should be performed in rapidly enlarging tumors and large tumors that are compressing vital structures (such as the trachea). In other cases, therapeutic radiation (radiotherapy, radiosurgery) is recommended as a first-line therapeutic approach. Observation may be considered in asymptomatic cases with a low risk of malignancy. An individual treatment is absolutely necessary in patients with HNPGLs. In patients with multiple HNPGLs, combination of different approaches may be required with a step-by-step approach. Before any treatment is started, these patients have to be extensively discussed at an interdisciplinary tumor board that is familiar with HNPGLs, and all the treatment options have to be discussed with the patient as well (Taieb, et al. 2014).

Vagal parathyroid tumors

Tumor origin and molecular genetics

Vagal parathyroid adenomas can be found within the vagus nerve (intravagal) in the neck or most often in close contact with the vagus nerve along its course within the carotid sheath or in the mediastinum.

In an autopsy study, microscopic collections of parathyroid chief cells were detected in about 6% of vagus nerves (Lack, et al. 1988). The origin of vagal parathyroid tissue is still controversial. In humans, the parathyroid glands develop from the 3rd and 4th pharyngeal pouches. The 3rd pouches differentiate into the thymus and inferior parathyroid glands (or parathyroid III), whereas the fourth pouches yield the superior parathyroid glands (or parathyroid IV) and the ultimobranchial body. The 3rd pouches lie between arches 3 and 4, and the 4th pouches between arches 4 and 6. Pharyngeal glands are thought to follow blood vessel networks to reach their final positions. Since arches 4 and 6 are innervated by the vagus nerve, it is therefore possible that a close association might occur between parathyroid tissue and the vagus nerve during morphogenetic movements. This association has led to the introduction of the concept of paravagal complex (Henry and Iacobone 2012).

Although substantial advances have been made, the mechanisms underlying parathyroid cell tumorigenesis are largely unknown. Germline mutations in MEN1 (Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia I), RET (Ret Proto-Oncogene), CDC73 (Cell Division Cycle 73, previously known as HRPT2), and CASR (calcium-Sensing Receptor) cause inherited primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT), which accounts for 5–10% of all cases. These mutations are commonly found in young patients with clinically non-familial PHPT (Starker, et al. 2012). Other parathyroid tumors may be due to activation of the WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway (Westin 2016). Inactivating mutations of the CDC73 tumor suppressor gene have been reported in hyperparathyroidism–jaw tumor (HPT–JT) syndrome-related adenomas and parathyroid carcinomas, in association with the loss of nuclear expression of the encoded protein, parafibromin.

The most frequent case of PHPT is a single parathyroid adenoma located in an eutopic position, followed by multiglandular disease (sporadic or hereditary) in 15–20% of cases, and ectopic glands found in 5–7% of cases. Ectopic positions can be a consequence of abnormal migration during embryogenesis (congenital) or secondary to acquired migration by gravity (due to gland weight). At la Timone university hospital based on a previous 2720 parathyroidectomies for PHPT, ectopic parathyroid glands were observed in 94 cases. The causes of ectopia were attributed to incomplete (5%) or excessive (34%) migration of the parathymic complex (PIII-derived), incomplete migration of PIV (7%), acquired ectopia (13%), subcapsular/intrathyroid (PIII-PIV) (27%), and the remaining cases were associated with the vagus nerve (14%) (Henry, et al. 2000). The lowest vagal parathyroid adenomas corresponded to sites where the inferior laryngeal nerves recur (i.e. around subclavian artery on right and aortic arch on left). Parathyroid hyperplastic glands associated with the vagus nerve can also be observed in the setting of MEN1and renal hyperparathyroidism.

Diagnosis and imaging

PHPT is the third most common endocrine disorder after diabetes and hyperthyroidism (al Zahrani and Levine 1997). Diagnosis relies on elevated ionized or total serum calcium with inappropriate normal or elevated serum PTH levels, and normal or elevated urinary calcium. Imaging is necessary when selecting candidates for a focused surgical approach. Neck ultrasound (US) imaging and parathyroid scintigraphy are commonly used. On neck US, parathyroid tumors usually appear as homogeneous hypoechoic well demarcated masses, which contrasts the hyperechoic appearance of thyroid tissue. In contrast to normal cervical nodes, no hyper-echoic hilum is seen. Calcification within the lesion is more common in parathyroid carcinoma or large parathyroid glands. Multiple small cysts can be seen. The use of color and power Doppler sonography usually shows marked intraparenchymal vascularity and in some cases, can identify the vascular pedicle. At the level of the thyroid gland (infra-hyoid neck), US with a modern high-frequency probe (5–14 MHz) can identify the vagus nerve (Ha, et al. 2011). Neck US can describe up to 20% of anterior anatomical variations of the vagus nerve course at the level of the infra-hyoid neck.

On parathyroid scintigraphy, vagal parathyroid adenomas often appear as sestamibi-avid lesions, with lateral cervical elongated nodules. There is a clear advantage of parathyroid scintigraphy with SPECT/CT over neck US in the localization of mediastinal parathyroid adenoma. MRI and 4-dimensional computed tomography (4D-CT) are usually performed in the presence of a mediastinal ectopic gland on scintigraphy or as the primary imaging modalities in some centers. 4D-CT consists in a multiphasic acquisition (non-enhanced, arterial and delayed phases) with a multi-detector CT scan (Hoang, et al. 2014). In contrast with normal lymph nodes or thyroid gland, parathyroid adenoma demonstrates avid contrast agent uptake in arterial phase and wash-out in delayed phase (figure 7). For ectopic parathyroid adenoma localization, accuracy of 4D-CT is high (>85%) (Hunter, et al. 2012). In the past, preoperative imaging has failed to detect ectopic parathyroid tumors, especially in old case series, which led to unsuccessful cervical exploration (Arnault, et al. 2010). Today, this in an extremely rare situation, especially with the use of 123I/sestamibi planar pinhole and SPECT/CT acquisition (Hindie, et al. 2015).

Figure 7. Vagal parathyroid adenoma located in the aortopulmonary window.

4D-CT with non-enhanced (A), arterial (B) and delayed (C) phases, volume rendering of 4D-CT (arterial phase, D), Sestamibi SPECT acquisition (F). Parathyroid adenoma is located in the aortopulmonary window (arrow), under aortic arch (*) and above pulmonary artery (**). As for cervical localizations, this supernumerary ectopic parathyroid adenoma demonstrates avid enhancement (B, E) and rapid wash-out (C) compared to mediastinal lymph nodes (arrow heads). This adenoma was detected by sestamibi SPECT (F).

Due to the very low frequency of ectopia not accessible via a cervical incision (<2%), 4D-CT (or MRI) are usually performed after surgical failure (Henry 2010). In case of a cervical image of uncertain origin, an image-guided fine needle aspiration for PTH assay may be performed (Bergenfelz, et al. 2009). Interesting results have been reported with 11C-methionine and 11C-choline PET in patients with persistent/recurrent hyperparathyroidism (Hessman, et al. 2008; Schalin-Jantti, et al. 2013). However, 11C-based PET imaging is difficult to implement in routine clinical practice due to low availability and very short half-life. Excellent results with 18F-fluorocholine have also been reported (Lezaic, et al. 2014; Michaud, et al. 2014; Orevi, et al. 2014) and this imaging modality may become an alternative to parathyroid scintigraphy at initial diagnosis. The use of selective venous sampling with assessment of PTH can be used in selected cases prior to reoperative surgery when other investigations are negative, equivocal, or discordant. A two-fold gradient of PTH level is required for confirmation of a parathyroid tumor and regionalization.

Treatment

Surgery is the only curative treatment for PHPT. Conventional surgery for PHPT relies on the inspection of the four parathyroid gland sites or indentification of at least four parathyroid glands through bilateral cervical exploration (Russell and Edis 1982). Today, bilateral neck exploration is not necessary for all patients if preoperative imaging studies show single-gland disease with the use of intraoperative PTH assay to confirm biochemical cure. A focused parathyroidectomy can be performed (e.g, mini-open surgery, endoscopy) when preoperative imaging is consistent with a single gland abnormality. If available, the assessment of serum intraoperative PTH monitoring can confirm complete removal of hypersecreting tissue. Ectopic glands can be a source of surgical failure. Positive localization of an ectopic gland is highly accurate and can facilitate a more focused surgical approach (Roy, et al. 2013).

Enucleation of a genuine intravagal adenoma can be performed without sacrificing the vagus nerve. Identification of an aortopulmonary adenoma by imaging can avoid useless cervical incisions with the potential risk of extensive dissections and morbidity.

In absence of preoperative parathyroid imaging or in situations with negative results, the surgeon will suspect an ectopic gland when a parathyroid gland is missing from its normal location or in the presence of four normal glands. The latter situation is observed in presence of a vagal parathyroid adenoma since they are almost always derived from a supernumerary gland. The surgeon will first search for an ectopic PIII or PIV gland depending on the missing gland. In presence of 4 normal glands, a supernumerary gland must be suspected. Most often, the adenoma is located in close contact with the thymus due to a fragmentation of PIII during the migration of the thyrothymic complex. The adenoma can be found in close contact with the vagus nerve or sometimes within the vagus nerve. Vagal parathyroid adenomas can be found in a high cervical intravagal position (Figure 6) or in the mediastinum. In the mediastinum, they may be located in the superior mediastinum or in the middle mediastinum in the aortopulmonary window (Figure 7). In the latter location, the adenoma cannot be removed through cervicotomy and require a thoracic approach. In cases of unsuccessful cervical exploration and subsequent, persistent disease, reoperation should be carefully decided, as the complication rate is higher than after intial surgery, even in experienced teams (Karakas, et al. 2013). Accurate localization is essential to increase success rate and reduce the risk of complications (Hessman et al. 2008).

Figure 6. Cervical intravagal parathyroid adenoma.

Axial CT with contrast injection (A) centered on the parathyroid adenoma (arrow) located in the vagus nerve path. Note the typical marked enhancement at arterial phase of injection of the parathyroid adenoma. Intraoperative view (B) showing the adenoma (arrow). In the present case, enucleation of the lesion, was not possible. Pathological analysis (C) revealed the presence of parathyroid tissue within the vagus nerve (*).

Table 2.

Differential diagnosis of post-styloid retropharyngeal masses: imaging features on MRI and molecular imaging

| Paraganglioma | Nodal Metastasis | Schwannoma | Neurofibroma | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRI | Numerous arterial feeders: Spin echo: Flow voids (“salt and pepper” appearance on T1 and T2-weighted images) TOF: hyperintense vessels (corresponding to flow voids) 3D (or 4D) Gadolinium angiograms: avid enhancement |

Variable appearance Well defined margins Moderate signal in T2 Restricted diffusion Heterogeneous enhancement usual |

Well defined margins Moderate-to-high signal intensity on T2 No restriction of diffusion Heterogeneous enhancement seen in large tumors with degenerative changes (cystic, pseudocystic) |

idem Schwannoma Central low signal on T2 may be seen (“target sign”) |

| PET/CT –18F-FDG | Moderate to high uptake (highly elevated in SDHx mutation carriers) | Low-to-high uptake depending on the primary tumor | Low-to-high uptake (even in benign cases) | Low uptake (high uptake values in malignant forms) |

| PET/CT –18F-FDOPA | High uptake | No significant uptake | No significant uptake | No significant uptake |

| PET/CT–68Ga-SSA | High uptake | No significant uptake (possible high uptake in nodal metastases from thyroid cancers or nasopharyngeal cancers) | No significant uptake | No significant uptake |

Learning points.

On successful completion of this activity, participants should be able to:

Better understand the embryological origin of vagal endocrine tumors and their molecular biology

Describe clinical, biological and imaging features of vagal endocrine tumors at presentation and their differential diagnosis

Understand contemporary management of vagal endocrine tumors

Key messages.

Understanding vagal endocrine tumors needs to establish a bridge between embryology and anatomy

Localization and characterization of vagal endocrine tumors require combination of anatomic and functional imaging techniques

Management of vagal parathyroid adenoma may require thoracic surgery

Vagal paraganglioma should be managed conservatively with either observation or radiation

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

References

- al Zahrani A, Levine MA. Primary hyperparathyroidism. Lancet. 1997;349:1233–1238. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)06176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archier A, Varoquaux A, Garrigue P, Montava M, Guerin C, Gabriel S, Beschmout E, Morange I, Fakhry N, Castinetti F, et al. Prospective comparison of (68)Ga-DOTATATE and (18)F-FDOPA PET/CT in patients with various pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas with emphasis on sporadic cases. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2016;43:1248–1257. doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3268-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnault V, Beaulieu A, Lifante JC, Sitges Serra A, Sebag F, Mathonnet M, Hamy A, Meurisse M, Carnaille B, Kraimps JL. Multicenter study of 19 aortopulmonary window parathyroid tumors: the challenge of embryologic origin. World journal of surgery. 2010;34:2211–2216. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0622-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold SM, Strecker R, Scheffler K, Spreer J, Schipper J, Neumann HP, Klisch J. Dynamic contrast enhancement of paragangliomas of the head and neck: evaluation with time-resolved 2D MR projection angiography. European radiology. 2003;13:1608–1611. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1717-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker CVH. The Embryology of Vagal Sensory Neurons. In: Undem BJ, Weinreich D, editors. Advances in Vagal Afferent Neurobiology. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2005. pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Baysal BE. Mitochondrial complex II and genomic imprinting in inheritance of paraganglioma tumors. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2013;1827:573–577. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baysal BE, Willett-Brozick JE, Lawrence EC, Drovdlic CM, Savul SA, McLeod DR, Yee HA, Brackmann DE, Slattery WH, 3rd, Myers EN, et al. Prevalence of SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD germline mutations in clinic patients with head and neck paragangliomas. Journal of medical genetics. 2002;39:178–183. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.3.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benn DE, Robinson BG, Clifton-Bligh RJ. 15 YEARS OF PARAGANGLIOMA: Clinical manifestations of paraganglioma syndromes types 1–5. Endocrine-related cancer. 2015;22:T91–103. doi: 10.1530/ERC-15-0268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergenfelz AO, Hellman P, Harrison B, Sitges-Serra A, Dralle H. Positional statement of the European Society of Endocrine Surgeons (ESES) on modern techniques in pHPT surgery. Langenbeck’s archives of surgery/Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Chirurgie. 2009;394:761–764. doi: 10.1007/s00423-009-0533-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boedeker CC, Neumann HP, Maier W, Bausch B, Schipper J, Ridder GJ. Malignant head and neck paragangliomas in SDHB mutation carriers. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery: official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2007;137:126–129. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Liu Q. Differentiation of malignant from benign pheochromocytomas with diffusion-weighted and dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance at 3.0 T. Journal of computer assisted tomography. 2012;36:361–366. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e31825975f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RJ, Patel D, Prodanov T, Nilubol N, Pacak K, Kebebew E. The Presence of SDHB Mutations Should Modify Surgical Indications for Carotid Body Paragangliomas. Annals of surgery. 2013 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson D, Kudva YC, Ebersold MJ, Thompson GB, Grant CS, van Heerden JA, Young WF., Jr Benign paragangliomas: clinical presentation and treatment outcomes in 236 patients. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2001;86:5210–5216. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.11.8034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Caumont-Prim A, Houzard C, Hignette C, Hernigou A, Halimi P, Niccoli P, Leboulleux S, Amar L, Borson-Chazot F, et al. Imaging work-up for screening of paraganglioma and pheochromocytoma in SDHx mutation carriers: a multicenter prospective study from the PGL.EVA Investigators. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2013;98:E162–173. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha EJ, Baek JH, Lee JH, Kim JK, Shong YK. Clinical significance of vagus nerve variation in radiofrequency ablation of thyroid nodules. European radiology. 2011;21:2151–2157. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry JF. Reoperation for primary hyperparathyroidism: tips and tricks. Langenbeck’s archives of surgery/Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Chirurgie. 2010;395:103–109. doi: 10.1007/s00423-009-0560-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry JF, Defechereux T, Raffaelli M, Lubrano D, Iacobone M. Supernumerary ectopic hyperfunctioning parathyroid gland: a potential pitfall in surgery for sporadic primary hyperthyroidism. Annales de chirurgie. 2000;125:247–252. doi: 10.1016/s0003-3944(00)00247-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry JF, Iacobone M. Ectopic Parathyroid Glands. Springer; Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hessman O, Stalberg P, Sundin A, Garske U, Rudberg C, Eriksson LG, Hellman P, Akerstrom G. High success rate of parathyroid reoperation may be achieved with improved localization diagnosis. World journal of surgery. 2008;32:774–781. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9537-5. discussion 782–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindie E, Zanotti-Fregonara P, Tabarin A, Rubello D, Morelec I, Wagner T, Henry JF, Taieb D. The role of radionuclide imaging in the surgical management of primary hyperparathyroidism. Journal of nuclear medicine: official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2015;56:737–744. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.156018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang JK, Sung WK, Bahl M, Phillips CD. How to perform parathyroid 4D CT: tips and traps for technique and interpretation. Radiology. 2014;270:15–24. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13122661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter GJ, Schellingerhout D, Vu TH, Perrier ND, Hamberg LM. Accuracy of four-dimensional CT for the localization of abnormal parathyroid glands in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. Radiology. 2012;264:789–795. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12110852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen I, Blanchet EM, Adams K, Chen CC, Millo CM, Herscovitch P, Taieb D, Kebebew E, Lehnert H, Fojo AT, et al. Superiority of [68Ga]-DOTATATE PET/CT to Other Functional Imaging Modalities in the Localization of SDHB-Associated Metastatic Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2015;21:3888–3895. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen I, Chen CC, Millo CM, Ling A, Taieb D, Lin FI, Adams KT, Wolf KI, Herscovitch P, Fojo AT, et al. PET/CT comparing Ga-DOTATATE and other radiopharmaceuticals and in comparison with CT/MRI for the localization of sporadic metastatic pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2016a doi: 10.1007/s00259-016-3357-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen I, Chen CC, Taieb D, Patronas NJ, Millo CM, Adams KT, Nambuba J, Herscovitch P, Sadowski SM, Fojo AT, et al. 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT in the Localization of Head and Neck Paragangliomas Compared with Other Functional Imaging Modalities and CT/MRI. Journal of nuclear medicine: official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2016b;57:186–191. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.161018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MH. Head and neck vascular anatomy. Neuroimaging clinics of North America. 1998;8:119–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakas E, Muller HH, Schlosshauer T, Rothmund M, Bartsch DK. Reoperations for primary hyperparathyroidism--improvement of outcome over two decades. Langenbeck’s archives of surgery/Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Chirurgie. 2013;398:99–106. doi: 10.1007/s00423-012-1004-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroiss A, Putzer D, Frech A, Decristoforo C, Uprimny C, Gasser RW, Shulkin BL, Url C, Widmann G, Prommegger R, et al. A retrospective comparison between (68)Ga-DOTA-TOC PET/CT and (18)F-DOPA PET/CT in patients with extra-adrenal paraganglioma. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2013;40:1800–1808. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2548-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuet ML, Kasbekar AV, Masterson L, Jani P. Management of tumors arising from the parapharyngeal space: A systematic review of 1,293 cases reported over 25 years. The Laryngoscope. 2015;125:1372–1381. doi: 10.1002/lary.25077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lack EE, Delay S, Linnoila RI. Ectopic parathyroid tissue within the vagus nerve. Incidence and possible clinical significance. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 1988;112:304–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezaic L, Rep S, Sever MJ, Kocjan T, Hocevar M, Fettich J. (1)(8)F-Fluorocholine PET/CT for localization of hyperfunctioning parathyroid tissue in primary hyperparathyroidism: a pilot study. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. 2014;41:2083–2089. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2837-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud L, Burgess A, Huchet V, Lefevre M, Tassart M, Ohnona J, Kerrou K, Balogova S, Talbot JN, Perie S. Is F-fluorocholine-PET/CT a new imaging tool for detecting hyperfunctioning parathyroid glands in primary or secondary hyperparathyroidism? The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2014:jc20142821. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann HP, Erlic Z, Boedeker CC, Rybicki LA, Robledo M, Hermsen M, Schiavi F, Falcioni M, Kwok P, Bauters C, et al. Clinical predictors for germline mutations in head and neck paraganglioma patients: cost reduction strategy in genetic diagnostic process as fallout. Cancer research. 2009;69:3650–3656. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves F, Huwart L, Jourdan G, Reizine D, Herman P, Vicaut E, Guichard JP. Head and neck paragangliomas: value of contrast-enhanced 3D MR angiography. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2008;29:883–889. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orevi M, Freedman N, Mishani E, Bocher M, Jacobson O, Krausz Y. Localization of Parathyroid Adenoma by 11C-Choline PET/CT: Preliminary Results. Clinical nuclear medicine. 2014;39:1033–1038. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000000607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang KP, Goh CH, Tan HM. Parapharyngeal space tumours: an 18 year review. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2002;116:170–175. doi: 10.1258/0022215021910447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccini V, Rapizzi E, Bacca A, Di Trapani G, Pulli R, Giache V, Zampetti B, Lucci-Cordisco E, Canu L, Corsini E, et al. Head and neck paragangliomas: genetic spectrum and clinical variability in 79 consecutive patients. Endocrine-related cancer. 2012;19:149–155. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy M, Mazeh H, Chen H, Sippel RS. Incidence and localization of ectopic parathyroid adenomas in previously unexplored patients. World journal of surgery. 2013;37:102–106. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1773-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell CF, Edis AJ. Surgery for primary hyperparathyroidism: experience with 500 consecutive cases and evaluation of the role of surgery in the asymptomatic patient. The British journal of surgery. 1982;69:244–247. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800690503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schalin-Jantti C, Ryhanen E, Heiskanen I, Seppanen M, Arola J, Schildt J, Vaisanen M, Nelimarkka L, Lisinen I, Aalto V, et al. Planar scintigraphy with 123I/99mTc-sestamibi, 99mTc-sestamibi SPECT/CT, 11C-methionine PET/CT, or selective venous sampling before reoperation of primary hyperparathyroidism? Journal of nuclear medicine: official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2013;54:739–747. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.109561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starker LF, Akerstrom T, Long WD, Delgado-Verdugo A, Donovan P, Udelsman R, Lifton RP, Carling T. Frequent germ-line mutations of the MEN1, CASR, and HRPT2/CDC73 genes in young patients with clinically non-familial primary hyperparathyroidism. Hormones & cancer. 2012;3:44–51. doi: 10.1007/s12672-011-0100-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez C, Rodrigo JP, Bodeker CC, Llorente JL, Silver CE, Jansen JC, Takes RP, Strojan P, Pellitteri PK, Rinaldo A, et al. Jugular and vagal paragangliomas: Systematic study of management with surgery and radiotherapy. Head & neck. 2013;35:1195–1204. doi: 10.1002/hed.22976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taieb D, Kaliski A, Boedeker CC, Martucci V, Fojo T, Adler JR, Jr, Pacak K. Current approaches and recent developments in the management of head and neck paragangliomas. Endocrine reviews. 2014;35:795–819. doi: 10.1210/er.2014-1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg R. Imaging and management of head and neck paragangliomas. European radiology. 2005;15:1310–1318. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-2743-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg R, Schepers A, de Bruine FT, Liauw L, Mertens BJ, van der Mey AG, van Buchem MA. The value of MR angiography techniques in the detection of head and neck paragangliomas. European journal of radiology. 2004;52:240–245. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hulsteijn LT, Dekkers OM, Hes FJ, Smit JW, Corssmit EP. Risk of malignant paraganglioma in SDHB-mutation and SDHD-mutation carriers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of medical genetics. 2012;49:768–776. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westin G. Molecular genetics and epigenetics of nonfamilial (sporadic) parathyroid tumours. Journal of internal medicine. 2016 doi: 10.1111/joim.12458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X, Wei S, Yu Y, Xia T, Zhao J, Gao S, Li Y, Gao M. Genetic and clinical characteristics of head and neck paragangliomas in a Chinese population. The Laryngoscope. 2012;122:1761–1766. doi: 10.1002/lary.23360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]