Abstract

Background: Atopic dermatitis has a significant impact on quality of life of children and families. Objective: It is important to assess gender differences in health-related quality of life in children with atopic dermatitis in order to effectively use health-related quality of life results. Methods: Children 5- to 16-years of age with atopic dermatitis from Italy, Singapore, Czech Republic, and Ukraine were divided into two groups (boys and girls). Each child in the group of boys was matched to a corresponding child in the group of girls from the same country whose age and scoring atopic dermatitis value were almost identical. Self-assessed health-related quality of life was measured by the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index. Results: The difference in overall Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index between boys and girls was not significant (P=0.33). Girls with atopic dermatitis assessed Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index item on embarrassment significantly higher (0.78±0.93 for boys and 1.14±0.93 for girls, P<0.05). Lowest scored items were the same and overall Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index results significantly correlated with scoring atopic dermatitis values in both groups. Two separate Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index items in boys and five items in girls significantly correlated with atopic dermatitis severity. The Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index item on affected sleep significantly correlated with the age of boys (r=0.38, P=0.02) and another Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index item on school work/holiday with the age of girls (r=0.59, P<0.01). Conclusion: Despite that the authors did not find differences in overall health-related quality of life results, girls were more embarrassed, self-conscious, upset, and sad because of atopic dermatitis. The authors’ results may influence the educational part of consultations of children with atopic dermatitis.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) has a significant impact on the quality of life (QoL) of affected children and their families.1-3 As in adults, childhood health-related (HR) QoL is commonly assessed by means of generic and/or specific instruments, including dermatology-specific and disease-specific measures.4 Measurement of HRQoL in pediatric dermatology helps to assess the impact of a single skin disease on a child’s life, to register the patient’s view on the efficacy of different treatment methods, educational programs, and consultations. It makes it possible to compare the impact of skin diseases and results of the treatment in children from different age groups on local, regional, national, and international levels.5 The vast majority of publications concerning HRQoL assessment in children with skin conditions is dedicated to AD.4 For the effective use of HRQoL results, it is important to know about existing gender differences in HRQoL assessment.

Contradictory results concerning gender differences in HRQoL of children with AD under four years measured by the Infant’s Dermatitis Quality of Life Index (IDQoL) questionnaire were previously reported. Park et al6 found more severe impact of AD on boys in 48 non-matched boys and 53 girls. Meanwhile, Alzolibani7 did not find gender differences in non-matched AD children. Chernyshov8 also had not found a significant gender difference of the overall IDQoL scores in 102 non-matched AD children, but found significant gender differences when each child in the group of boys was matched to a corresponding child in the group of girls whose age in months and scoring atopic dermatitis (SCORAD) value were almost identical.8

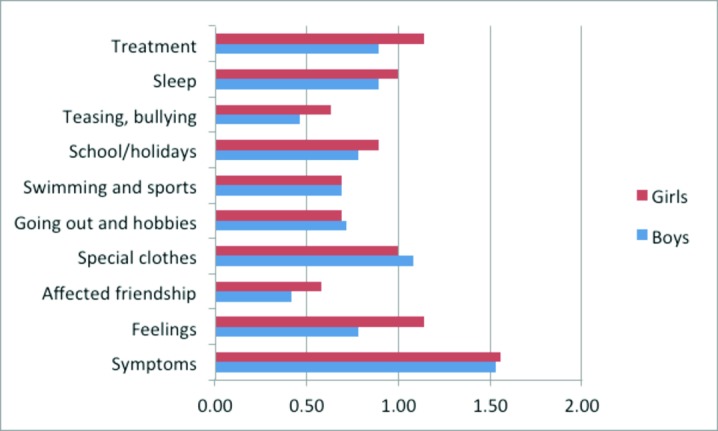

Figure 1.

CDLQI results in boys and girls with atopic dermatitis

Kiebert et al9 found a significant gender difference in self-assessed HRQoL of older children with AD. The Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) scores were significantly higher in girls in that study. Hon et al10 and Ang et al11 reported that girls had more problems with issues of clothes and shoes than did boys10 and had higher scores on the swimming and other sports item.11 Recently, the authors did not find significant gender differences in self-assessed HRQoL of non-matched children from Ukraine, Italy, Czech Republic, and Singapore.12

In this study, the authors decided to analyze gender differences in self-assessed HRQoL of children with AD matched by country, age, and disease severity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

For the study, data on children with AD from 5 to 16 years of age who had no other manifest diseases from four countries (Ukraine, Czech Republic, Singapore, and Italy) were used.

One hundred sixty-seven children with AD from Ukraine, Singapore, Italy, and Czech Republic were divided into two groups based on their sex and matched according to age and SCORAD13 values. Each child in the group of boys was matched to a corresponding child in the group of girls from the same country whose age and SCORAD value were almost identical. Age difference in pairs did not exceed one year. Difference in SCORAD in pairs did not exceed 3.0 (but both children in pairs were with the same severity grade: severe, moderate, or mild). AD with a SCORAD higher than 40 was regarded as severe, whereas AD with a SCORAD below 20 was regarded as mild.14

Thus, 36 girls and 36 boys (16 from Italy, 10 from Singapore, 20 from Czech Republic, and 26 from Ukraine) with AD were selected for further investigation. Diagnosis of AD was made using Hanifin and Rajka or Williams criteria.15,16 Disease severity was estimated using the SCORAD—a clinical disease severity instrument that combines information on the involved area of skin, as well as objective and subjective symptoms in patients with AD.13 Self-assessed HRQoL was assessed by means of the CDLQI.17 The CDLQI HRQoL questionnaire is designed for use in children with skin conditions who are 5 to 16 years of age. The CDLQI questionnaire is self-explanatory and can be simply handed to the patient who is asked to fill it in with the help of the child’s parent or guardian. The 10 questions of the CDLQI cover six areas of daily activities including symptoms and feelings, leisure, school or holidays, personal relationships, sleep, and treatment. Each question is answered on a 4-point Likert scale scored from 0 to 3. These are added to give a minimum score of 0 and maximum score of 30. Higher scores indicate a poorer quality of life. In order to help the clinical interpretation of the CDLQI scores, a banding system (consisting of 5 bands) has been proposed.18 According to this system, a CDLQI score of 0-1 = no effect on child’s life, 2-6 = small effect on child’s life, 7-12 = moderate effect on child’s life, 13-18 = very large effect on child’s life, and 19-30 = extremely large effect on child’s life. Original (English), Ukrainian, Czech, and Italian versions of the CDLQI questionnaire were used. Data on validation of original (English) and Ukrainian versions of the CDLQI were previously published.17,19 Permission to use the CDLQI questionnaire was granted by its authors and copyright owners Professor Andrew Y. Finlay and Dr. M.S. Lewis-Jones. Ethical permission for the study was granted by the local ethic research committees.

Data was presented as mean ± standard deviation of the mean. Paired t-test (two-sided), Fisher’s exact test (two-sided) and non-parametric correlation (Spearman’s r) were used. The results were considered significant if P<0.05.

RESULTS

Mean age, SCORAD, and overall CDLQI scores of selected boys and girls with AD are presented in Table 1. The difference in overall CDLQI between boys and girls was not statistically significant (P=0.33). No differences were found in distribution of the overall CDLQI scores of boys and girls with AD according to the CDLQI banding (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Mean age, SCORAD and overall CDLQI scores of boys and girls with atopic dermatitis

| BOYS (n=36) | GIRLS (n=36) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 9.69±3.21 | 9.83±3.27 |

| SCORAD | 28.14±19.55 | 28.19±20.70 |

| CDLQI | 8.31 ±6.33 | 9.25±6.73 |

TABLE 2.

Distribution of the overall CDLQI scores of boys and girls with AD according to the CDLQI banding

| CDLQI BANDING | BOYS (n=36) | GIRLS (n=36) |

|---|---|---|

| No effect | 2 | 1 |

| Small effect | 14 | 12 |

| Moderate effect | 13 | 14 |

| Very large effect | 3 | 5 |

| Extremely large effect | 4 | 4 |

Subscale on “symptoms and feelings” was assessed significantly higher by girls with AD (P<0.05). However, there was no gender difference in assessment of the CDLQI item on symptoms (1.53±0.77 for boys and 1.56±0.77 for girls, P=0.42). A gender difference was found for the item on feelings. Girls with AD assessed the CDLQI item on, “How embarrassed or self conscious, upset or sad have you been because of your skin?” significantly higher than boys (0.78±0.93 for boys and 1.14±0.93 for girls, P<0.05).

Lowest scored items were the same for boys and girls: “How much has your skin affected your friendships?”, “How much trouble have you had because of your skin with other people calling you names, teasing, bullying, asking questions, or avoiding you?” and “How much have you avoided swimming or other sports because of your skin trouble?” The highest scored CDLQI item was “How itchy, scratchy, sore, or painful has your skin been?” Meanwhile, the second highly scored item in boys was: “How much have you changed or worn different or special clothes or shoes because of your skin?” and in girls: “How embarrassed or self conscious, upset, or sad have you been because of your skin?”

Overall, CDLQI results significantly correlated with SCORAD and not significantly with the age of boys and girls (Table 3). Correlations between SCORAD and age was extremely poor (r=0.01, P=0.95 for boys and r=0.03, P=0.84 for girls).

TABLE 3.

Correlations of the overall CDLQI scores with SCORAD and age of boys and girls with AD

| CDLQI SCORES | ||

|---|---|---|

| BOYS (n=36) | GIRLS (n=36) | |

| SCORAD | r=0.33, P<0.05 | r=0.47, P<0.01 |

| Age | r=0.24, P=0.16 | r=0.29, P=0.08 |

Two separate CDLQI items in boys and five items in girls significantly correlated with AD severity (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Correlations of separate CDLQI items scores with SCORAD in boys and girls with AD

| CDLQI ITEMS | SCORAD | |

|---|---|---|

| BOYS (n=36) | GIRLS (n=36) | |

| How itchy, “scratchy”, sore, or painful has your skin been? | r=0.60, P<0.01 | r=0.59, P<0.01 |

| How embarrassed or self-conscious, upset or sad have you been because of your skin? | r=0.41, P=0.01 | r=0.39, P=0.02 |

| How much has your skin affected your friendships? | r=0.25, P=0.14 | r=0.45, P<0.01 |

| How much have you changed or worn different or special clothes or shoes because of your skin? | r=0.24, P=0.16 | r=0.20, P=0.24 |

| How much has your skin trouble affected going out, playing, or doing hobbies? | r=0.25, P=0.14 | r=0.45, P<0.01 |

| How much have you avoided swimming or other sports because of your skin trouble? | r=0.27, P=0.12 | r=0.43, P<0.01 |

| How much did your skin problem affect your school work/interfered with your enjoyment of the holiday? | r=0.25, P=0.15 | r=0.31, P=0.06 |

| How much trouble have you had because of your skin with other people calling you names, teasing, bullying, asking questions, or avoiding you? | r=0.18, P=0.30 | r=-0.01, P=0.99 |

| How much has your sleep been affected by your skin problem? | r=0.10, P=0.54 | r=0.31, P=0.06 |

| How much of a problem has the treatment for your skin been? | r=0.10, P=0.56 | r=0.14, P=0.42 |

A single CDLQI item on “How much has your sleep been affected by your skin problem?” significantly correlated with the age of boys (r=0.38, P=0.02) and another single item “How much did your skin problem affect your school work/interfered with your enjoyment of the holiday?” significantly correlated with the age of girls (r=0.59, P<0.01).

DISCUSSION

In contrast with Kiebert et al,9 in the authors’ study, overall CDLQI results of girls with AD were not significantly higher than boys’ results. Baici et al20 reported no statistically significant differences in the CDLQI subscales scores according to the gender they reported significant difference in “symptoms and feeling” subscale. However, symptoms were assessed almost identically by both genders in the authors’ study.

Despite the fact that the authors did not find differences in overall HRQoL results, girls were more embarrassed, self-conscious, upset, and sad because of AD. These problems together with subjective complaints on itching, scratching and pain correlated with disease severity in both sexes. Meanwhile, effect on friendship, going out, playing, or doing hobbies and avoidance of swimming or other sports correlated with SCORAD exclusively in girls and were scored lowest by both sexes.

The fact that the item on name calling, teasing, bullying, asking questions, or avoiding was one of the lowest scored items and had extremely poor correlation with AD severity in girls indicates that AD impact on friendship, going out, playing, or doing hobbies and avoiding swimming or other sports correlates with AD severity not because of other people’s reactions, but mostly because girls are more embarrassed, self-conscious, upset, and sad. It may also be related to having problems at school and age. We can speculate that older school girls are more concentrated on social aspects of school life including romantic relations and it is more difficult for them to appear in class with manifestations of AD. Meanwhile, in a recent study by Halvorsen et al,21 18- to 19-year-old men with current eczema were less likely to have had romantic relationships. It was previously reported that avoidance strategies are typical for AD patients, resulting in marked behavioral avoidance of intimate situations.22 Problems in AD patients in that study were mediated more by appearance and texture of non-genital skin than by involvement of genital skin. However, in asthma, another atopic disease, female subjects reported significantly greater missed days of school compared to males despite no difference in asthma severity.23 Thus, this gender difference may be present even without skin involvement. Jirakova et al24 previously reported that 14- to 18-year-old children with AD had more problems during school or holidays than 7- to 13-year-old children. We can speculate that the girls’ answers caused this difference.

Meanwhile, correlation of the CDLQI item “How much has your sleep been affected by your skin problem?” exclusively with the age of boys’ may be explained by the results of other published studies. Thus, the findings of Sadeh et al25 reflected significant age differences, indicating that older children have more delayed sleep onset times and increased reported daytime sleepiness. Girls were found to spend more time in sleep and to have an increased percentage of motionless sleep. Gaina et al26 also found that boys’ sleep was less efficient and more fragmented during the entire week in comparison to that of the girls. Finally, Krishnan and Collop27 found that gender differences in sleep become apparent after the onset of puberty. In the authors’ study, sleep problems in boys correlated with age and did not correlate with disease severity. Thus, these problems may be more related to physiologic peculiarities of puberty.

Despite the authors’ expectations, they did not find gender difference in problems with issues of clothes and shoes, as reported by Hon et al.10

In the study by Ang et al,11 the CDLQI item on problems with swimming and other sports was the second highly scored item in girls and had a significantly higher impact on HRQoL of girls. In the authors’ study, this CDLQI item was assessed as one of the lowest scored items by both sexes. This may be explained by poorer involvement of the authors’ study population in sport activities and swimming.

Gender differences in self-assessed HRQoL of 5- to 16-year-old children with AD in the authors’ study appeared to be less prominent than in younger AD children assessed by disease-specific proxy questionnaire.8 The same principals of matching of AD patients were used in both studies. Use of questionnaire in a single center with a particular language version could be thought to restrict the generalizability of the findings of the study. However, recent international studies reported that parents of AD children from different countries assess their children’s HRQoL in a quite similar manner.28,29

The author’s present international study confirmed the tendency for AD to have more of a severe impact on girls’ lives. These results may influence the educational part of consultations with children who have AD. Meanwhile, psychological problems increase with AD disease severity in both sexes, and girls in general need more attention to their AD-related psychological problems. In particular, specialists’ advice should focus on the prevention of avoidance behavior formation in girls who have more severe AD and older adolescent girls in cases of absence of teasing and bullying. Otherwise, progression of such avoidance behavior may affect friendships, hobbies, sports, and even school studies in older girls and may lead to more serious consequences in their future life.

Older boys with AD should receive general recommendations on improving their sleep. According to the United States National Sleep Foundation recommendations, children of all ages should fall asleep independently, go to bed before 9:00 pm, have an established bedtime routine, include reading as part of their bedtime routine, refrain from caffeine, and sleep in bedrooms without televisions.30 Those who exercize vigorously in the morning also have favorable sleep outcomes, including greater likelihood of reporting good sleep quality and lower likelihood of waking unrefreshed. Evening exercise is not associated with worse sleep31 and may increase objectively assessed sleep efficiency.32

The main limitation of this study is the different number of patients per country, which may cause speculation on cross-cultural inequivalence. However, a recent study revealed that highest and lowest scored CDLQI items in these countries are quite common.12 The relatively low number of patients in this study is the result of the scrupulous matching process.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study on gender differences of self-assessed HRQoL in children with AD when patients were well-matched. The results of this study may influence the educational portion of consultations with children who have AD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Professor A.Y. Finlay and Dr. M.S. Lewis-Jones for permission to use the CDLQI and the DFI questionnaires.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE:The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Beattie PE, Lewis-Jones MS. An audit of the impact of a consultation with a pediatric dermatology team on quality of life in infants with atopic eczema and their families: further validation of the Infants’ Dermatitis Quality of Life Index and Dermatitis Family Impact score. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:1249–1255. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monti F, Agostini F, Gobbi F, et al. Quality of life measures in Italian children with atopic dermatitis and their families. Ital J Pediatr. 2011:37–59. doi: 10.1186/1824-7288-37-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chernyshov PV, Kaliuzhna LD, Reznikova AA, Basra MK. Comparison of the impairment of family quality of life assessed by disease-specific and dermatology-specific instruments in children with atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;29(6):1221–1224. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chernyshov P, de Korte J, Tomas-Aragones L, Lewis-Jones S. EADV Taskforce’s recommendations on measurement of health-related quality of life in paediatric dermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2306–2316. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chernyshov P. Dermatological quality of life instruments in children. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013;148:277–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park CK, Park CW, Lee CH. Quality of life and the family impact of atopic dermatitis in children. Korean J Dermatol. 2007;45:429–438. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alzolibani A. Impact of atopic dermatitis on the quality of life of Saudi children. Saudi Med J. 2014;35:391–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chernyshov PV. Gender differences in health-related and family quality of life in young children with atopic dermatitis. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:290–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.04997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiebert G, Sorensen SV, Revicki D, et al. Atopic dermatitis is associated with a decrement in health-related quality of life. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:151–158. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hon KL, Leung TF, Wong KY, et al. Does age or gender influence quality of life in children with atopic dermatitis? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:705–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.02853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ang SB, Teng CWC, Monika TP, Wee H. Impact of atopic dermatitis on health-related quality of life among infants and children in Singapore: a pilot cross-sectional study. Proceedings of Singapore Healthcare. 2014;23:100–107. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chernyshov PV, Ho RC, Monti F, et al. An international multi-center study on self-assessed and family quality of life in children with atopic dermatitis. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2015;23:247–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: the SCORAD index. Consensus Report of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatology. 1993;186:23–31. doi: 10.1159/000247298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ring J, Alomar A, Bieber T, et al. Guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis). Part I. J European Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1045–1060. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanifin GM, Rajka G. Diagnostic feature of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1980;92(Suppl):44–47. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams HC, Burney PG, Pembroke AC, Hay RJ. The U.K. Working Party’s Diagnostic Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis. III. Independent hospital validation. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:406–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb08532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis-Jones MS, Finlay AY. The Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI): initial validation and practical use. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:942–949. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb16953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waters A, Sandhu D, Beattie P, et al. Severity stratification of Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) scores. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(Suppl 1):121. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chernyshov PV. Creation and cross-cultural adaptation of Ukrainian versions of questionnaires for assessment of quality of life of children with atopic dermatitis and their families. Lik Sprava. 2008;1-2:124–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balci D, Sangün Ö, Inandi T. Cross validation of the Turkish version of Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index. J Turk Acad Dermatol. 2007;1:71402a. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halvorsen JA, Lien L, Dalgard F, et al. Suicidal ideation, mental health problems, and social function in adolescents with eczema: a population-based study. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1847–1854. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magín Ρ, Heading G, Adams J, Pond D. Sex and the skin: a qualitative study of patients with acne, psoriasis and atopic eczema. Psychol Health Med. 2010;15:454–462. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2010.484463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee JH, Haselkorn T, Chipps BE, Miller DP, Wenzel SE. Tenor Study Group. Gender differences in IgE-mediated allergic asthma in the epidemiology and natural history of asthma: Outcomes and Treatment Regimens (TENOR) study. J Asthma. 2006;43:179–184. doi: 10.1080/02770900600566405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiráková A, Vojácková Ν, Göpfertová D, Hercogová J. A comparative study of the impairment of quality of life in Czech children with atopic dermatitis of different age groups and their families. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:688–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sadeh A, Raviv A, Gruber R. Sleep patterns and sleep disruptions in school-age children. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:291–301. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.36.3.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaina A, Sekine M, Hamanishi S, et al. Gender and temporal differences in sleep-wake patterns in Japanese schoolchildren. Sleep. 2005;28:337–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krishnan V, Collop NA. Gender differences in sleep disorders. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12:383–389. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000245705.69440.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chernyshov P, Jiráková A, Hercogová J. Comparative study of the quality of life of children with atopic dermatitis from Ukraine and the Czech Republic. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1483–1484. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chernyshov PV, Jirakova A, Ho RC, et al. An international multicenter study on quality of life and family quality of life in children with atopic dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Lepra. 2013;79:52–58. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.104669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mindell JA, Meltzer LJ, Carskadon MA, Chervin RD. Developmental aspects of sleep hygiene: findings from the 2004 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Poll. Sleep Med. 2009;10:771–779. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buman MP, Phillips BA, Youngstedt SD, et al. Does nighttime exercise really disturb sleep? Results from the 2013 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Poll. Sleep Med. 2014;15:755–761. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brand S, Kalak N, Gerber M, et al. High self-perceived exercise exertion before bedtime is associated with greater objectively assessed sleep efficiency. Sleep Med. 2014;15:1031–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]