Abstract

Background

This is a retrospective prognostic study on soft tissue injury following isolated greater tuberosity (GT) fractures of the proximal humerus with respect to the relationship between rotator cuff tears and GT displacement.

Methods

Forty-three patients with isolated GT fractures were recruited and evaluated with a standardized interview and physical examination, quality of life and shoulder function questionnaires (Western Ontario Rotator Cuff Index, SF-12 Version 2, Constant, Quick-Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand, Visual Analogue Scale), standard shoulder radiographs and an ultrasound. The main outcome measurements were: incidence of rotator cuff tears and atrophy, biceps pathology and sub-acromial impingement; superior displacement of the GT fragment; and questionnaire scores.

Results

Mean age was 57 years (31 years to 90 years) with a follow-up of 2.4 years (0.8 years to 6.8 years). In total, 16% had a full rotator cuff tear and 57% showed subacromial impingement on ultrasound. Full rotator cuff tears and supraspinatus fatty atrophy significantly correlated with decreased function and abduction strength. Significant atrophy (>50%) of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus, without a rotator cuff tear, was correlated with the worst function in the presence of a residual displacement of the greater tuberosity at the last-follow-up (7 mm).

Conclusions

Residual displacement, full rotator cuff tear and muscle atrophy are associated with the worst outcomes. Soft tissue imaging could benefit patients with an unfavourable outcome after a GT fracture to treat soft tissue injury.

Keywords: greater tuberosity fracture, muscles atrophy, residual displacement of GT, rotator cuff tears, soft tissue imaging, soft tissue pathology

Introduction

Proximal humerus fractures are common, affecting 73 per 100, 000 individuals in North America.1 Twenty percent of these injuries are isolated fractures of the greater tuberosity (GT).2 The GT is the insertion site for three rotator cuff tendons (supraspinatus, infraspinatus and teres minor) and even minor amounts of displacement can significantly impact function and range-of-motion of the affected joint.3–8 Additionally, because of the proximity of the biceps tendon to the GT, partial or full tears and tendinopathy may occur following GT fracture.

Functional outcomes following proximal humerus fractures are highly variable, with reported Constant scores of between 34 and 100.9 It has been suggested that undetected rotator cuff tears may be a significant cause of poor outcome and up to 40% of individuals will have a full-thickness rotator cuff tear following proximal humerus fracture.10 Fatty muscle atrophy of the rotator cuff following rotator cuff tear has also been correlated with worse functional outcome.11 However, the impact of rotator cuff pathology or atrophy on functional outcome following isolated GT fracture has not yet been described.

The purpose of the present study was to describe the incidence of rotator cuff and biceps pathology following isolated GT fracture and to assess their impact on objective and subjective functional outcomes.

Materials and Methods

A prospective trauma database at a level 1 trauma centre was retrospectively queried to identify all cases of isolated GT fractures that presented between July 2007 and April 2011. Specific inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1. All eligible patients were invited by phone to participate in the study, which consisted of a follow-up visit at the orthopaedic clinic, the completion of quality of life questionnaires, a physical examination, shoulder radiographs, and a shoulder ultrasound. Local ethics review board approval was obtained prior to the commencement of this study.

Table 1.

List of inclusion and exclusion criteria for patients enrolled in the present study.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Isolated fractures of the greater tuberosity Conservative treatment Skeletal maturity Minimum 1 year of follow-up Good quality radiographs of the acute fracture with minimum anteroposterior and lateral views | Local tumour, infection or significant glenohumeral arthritis Previous injury of the same upper limb Presence of prior neurological deficit of either upper limb Patient unable or unwilling to collaborate as a result of psychiatric illness or language barrier |

During the follow-up visit, all patients were interviewed and examined by a single senior resident (JM). The visits consisted of demographic data collection (including age, sex, tobacco use and employment status) and the completion of quality of life and shoulder function questionnaires: Western Ontario Rotator Cuff Index (WORC),12 SF-12® Health Survey version 2.0 (SF-12 v2),13 Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand Outcome Measure – Shortened version (Quick-DASH),14 and a visual analogue pain scale (0 to 10). The range of motion of both shoulders and elbows was evaluated by a single physiotherapist and the shoulder abduction force was tested with a Lafayette 01163 Manual Muscle Tester (Lafayette Instrument Co., Lafayette, IN, USA) using the Constant score method.15 Finally, the results were compared between the injured and uninjured shoulders.

The financial compensation received by the patients during their convalescence was also noted because this has been shown to have a significant impact on final outcome.16,17 In our region, patients may receive salary insurance coverage either from private insurance or public worker’s compensation insurance. Direct treatment costs are covered by a universal public healthcare system for all patients.

Shoulder radiographs from the initial, follow-up and study visits were reviewed and the initial and subsequent GT displacement was measured. The GT fractures were classified according to the Neer and AO Classifications, which were developed for proximal humerus fractures. The Neer Classification defines GT fractures as displaced if the GT fragment is translated by ≥1 cm or angulated by ≥45° with respect to the humeral shaft. However, Neer observed that isolated GT fractures tended towards a poorer outcome with even minimal displacement.18 The AO Classification divides isolated GT fractures into three types: nondisplaced (<5 mm), displaced (≥5 mm) or associated with glenohumeral dislocation. The 5-mm cut-off for displacement was chosen for this classification in recognition of the poor outcome following GT fractures with even minimal displacement.19 All of the GT fractures were also classified according to the morphological classification.20 This classification divides GT fractures into ‘avulsion’, ‘split’ or ‘depression’ types depending on GT fragment shape, location and size.20

The modality and duration of treatment for each patient was retrieved from the medical record and the presence or absence of glenohumeral dislocation at the time of fracture was also recorded.

Finally, all patients underwent shoulder ultrasound examination by a single experienced musculoskeletal radiologist. Ultrasound was chosen for this study because it allowed for the dynamic evaluation of sub-acromial impingement, which is a significant concern in GT fractures.3,7 Additionally, ultrasound is comparable to (and for spatial resolution and blood flow, better than) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for rotator cuff imaging.21–23 Ultrasound is relatively inexpensive, readily available, and both reliable and accurate in the evaluation of fatty atrophy in the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles.24

A standardized checklist was used to guide the ultrasound examination and to record pathological findings. The supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis and biceps tendons were examined for evidence of tendinosis and for partial or complete tears. Atrophy of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles was measured using the occupation ratio validated by Khoury et al.25 and compared with the contralateral shoulder. Fatty infiltration was assessed based on muscle echogenicity and pennate pattern and graded as: none, less than 50, or more than 50%. The ipsilateral trapezius muscle was used as the normal control. The location of the biceps tendon, with respect to its tunnel, was also noted and a dynamic evaluation for subacromial impingement was performed.

Statistical analysis

A power analysis using a two-tailed t-test (α = 0.05, β = 0.8) determined that the minimum number of patients required for the study was 42. This was based on a minimum clinically relevant difference of 15 points on the WORC questionnaire (SD 16.8) between patients with and without rotator cuff tears and an estimated 40% prevalence of full rotator cuff tears. This estimate was taken from the literature on proximal humerus fractures.4

The impact of demographic data, fracture characteristics, financial compensation and the presence of rotator cuff pathology on functional outcome following isolated GT fracture was then analyzed. Student’s t-test was used for continuous data and the chi-squared test was used for categorical data. Associations at a level of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

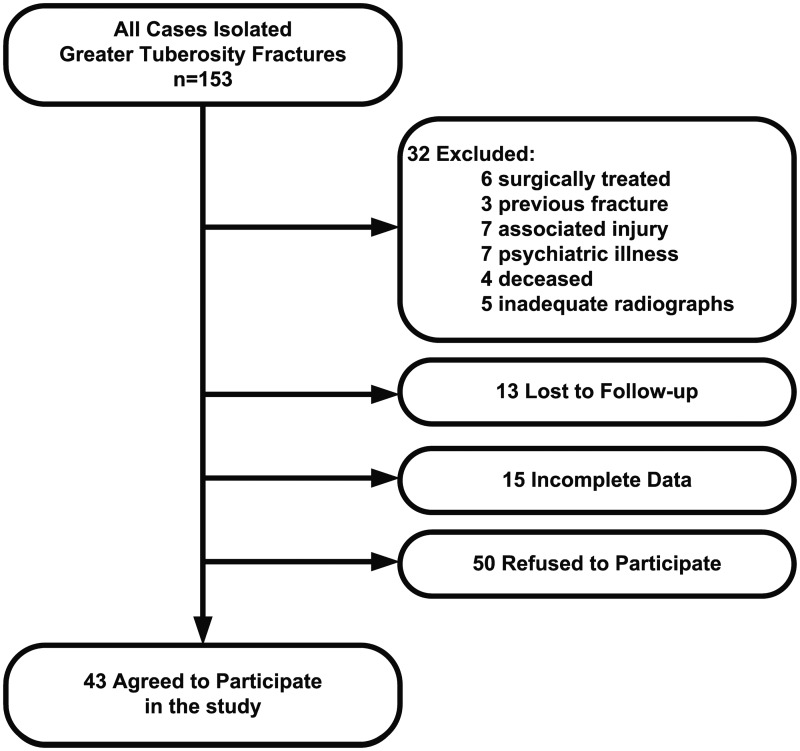

A total of 153 cases of isolated greater tuberosity fractures were identified and 93 patients met the inclusion criteria. Forty-three of these patients agreed to participate in the clinical study (Fig. 1). The demographic profile, as well as follow-up time, fracture characteristics and treatment modality, were compared between patients who agreed to participate and those who refused (Table 2). There were no statistically significant differences between the patients who agreed to participate in the clinical study and those who did not.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of all patients meeting inclusion criteria and reasons for exclusion from the present study.

Table 2.

Demographic information, fracture characteristics, and treatment method for the entire study population.

| Demographics | Participants (n = 43) | Eligible patients who refused (n = 50) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 57 SD 13.5; range 31 to 90 | 58 years SD 15; range 23 to 84 | 0.76 |

| Sex | Male: 19 (44%) Female: 24 (56%) | Male: 16 (32%) Female: 34 (68%) | 0.23 |

| Fracture side | Left: 23 (53%) Right: 20 (47%) | Left: 20 (40%) Right: 30 (60%) | 0.19 |

| Treatment | Surgery: 0 (0%) Nonsurgical: 43 (100%) | Surgery: 4 (8%) Nonsurgical: 46 (92%) | 0.06 |

| Glenohumeral dislocation | Yes: 13 (31%) No: 29 (69%) | Yes: 17 (34%) No: 33 (66%) | 0.76 |

Patients who agreed to participate in the clinical study are compared with those who refused. Values are expressed as absolute number (n), percentage (%), or mean (SD) and range, where appropriate

The average age of the study population was 57 years (SD 13.5 years), fifty-six percent of patients were female and the average follow-up was 2.4 years (range 1 year to 7 years). Thirty-one percent of patients had concurrent glenohumeral dislocation at the time of injury. All patients underwent non-operative management for their GT fracture.

The mean initial displacement of the GT fragment was only 2.2 mm, although this varied greatly (from 9 mm inferior to 22 mm superior). Inferior or superior GT displacement was defined relative to the normal anatomic position of the GT. Only five patients had more than 5 mm of displacement. The GT fracture morphology was distributed as: seven patients with depression type, 20 with avulsion type and 16 with split fracture type.

Sonographic findings

The supraspinatus tendon had the greatest number of full 10.3% (n = 4/39) and partial tears 61.5% (n = 15/39). The infraspinatus had 2.6% (n = 1/39) full and 17.9% (n = 7/38) partial tears; the subscapularis had 2.6% (n = 1/39) full and 7.7% (n = 7/39) partial tears; and the biceps had 0% (n = 0/38) full and 5.3% (n = 1/38) partial tears. Despite having fewer tears, the infraspinatus muscle demonstrated more atrophy and fatty infiltration [49% (n = 19/39) and 62% (n = 24/39), respectively] compared to the supraspinatus muscle [11% (n = 4/37) and 13% (n = 5/39), respectively]. The long head of the biceps showed signs of acute tenosynovitis in 5.3% (n = 2/38) of patients and biceps tendon subluxation occurred in 29% (n = 11/37). Sub-acromial impingement was also present in more than half of patients 56% (n = 22/39). The total number of patients in these analyses varied from 37 to 43 because some ultrasounds were incomplete as a result of technical difficulties, body habitus, patient discomfort or stiffness.

Functional results

The demographic variables studied (age, sex, side of injury, smoking, employment status) were not significantly related to functional outcome, except for work status and financial compensation. Unemployed patients had significantly higher Constant score improvements compared to employed patients (13 versus 5). Patients with private insurance had decreased Quick-Dash Main scores compared to uninsured or publicly insured (workers compensation or auto insurance) patients (14 versus 26, p = 0.05). However, none of the other functional scores varied significantly according to insurance status (Table 3).

Table 3.

Table of functional outcome measure scores compared between types of financial compensation [private, public (worker’s compensation)].

| Outcome measure | Private insurance | Public insurance or Medicare | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WORC (%) | 83 (23) | 62 (34) | 0.14 | |

| Quick-Dash Main | 14 (18) | 36 (27) | 0.05 | |

| SF-12 | Physical | 51 (9) | 46 (9) | 0.25 |

| Mental | 53 (7) | 47 (10) | 0.17 | |

| Pain score | 1.6 (2.3) | 2.8 (3) | 0.36 | |

| Constant score difference | 1 (10) | 11 (15) | 0.13 | |

| Strength loss (kg) | 2 (5) | 5 (7) | 0.48 | |

| ROM injured side (°) | Flexion | 170 (12) | 172 (19) | 0.81 |

| Abduction | 167 (18) | 156 (39) | 0.43 | |

| External rotation | 76 (8) | 74 (17) | 0.60 | |

Values are expressed as the mean (SD). Significance is set at p < 0.05 and significant values are shown in bold with the corresponding p value. WORC, Western Ontario Rotator Cuff Index, expressed as a percentage of total possible score. SF-12, Short-Form Health Survey version 2; scores are provided for the physical and mental components separately and are out of a maximum score of 100. The Constant score difference is the absolute difference in constant score between the injured and uninjured shoulders. Strength loss is the absolute difference in abduction force (kg) between the injured and uninjured shoulders. ROM, range of motion; expressed in degrees (°).

GT fractures in this cohort were relatively stable and did not displace significantly between the initial and final radiographs (3.6 mm versus 1.1 mm; p = 0.09). Of the GT fractures that were minimally displaced at initial presentation (<5 mm), only two of 36 (6%) migrated to >5 mm superior displacement at final follow-up. Concomitant glenohumeral dislocation was not predictive of greater GT displacement, nor of a higher incidence of rotator cuff tears. However, GT displacement at final follow-up was significantly higher in patients with supraspinatus atrophy than in those without supraspinatus atrophy (12.8 mm versus 1.1 mm; p = 0.001). This was not necessarily associated with a concomitant rotator cuff tear.

The presence of abnormalities found on ultrasound examination had a negative impact on functional outcome. The presence of supraspinatus fatty infiltration was associated with greater loss of abduction strength (8 kg with versus 2 kg without fatty infiltration; p = 0.01) and lower SF-12 Physical scores (35 with versus 48 without fatty infiltration; p = 0.01). Infraspinatus fatty infiltration was also associated with greater loss of abduction strength (4 kg with versus 0.3 kg without fatty infiltration; p = 0.01). A detailed breakdown of the functional outcomes associated with abnormalities found on ultrasound examination can be found in Table 4 (for rotator cuff tears and atrophy) and Table 5 (for biceps pathology and subacromial impingement).

Table 4.

The impact of rotator cuff tears and rotator cuff atrophy on functional outcome measures.

|

|

Tears in the rotator cuff (any) |

Full tears in the rotator cuff |

Supraspinatus atrophy (any) |

Supraspinatus fatty infiltration (any) |

Infraspinatus atrophy (any) |

Infraspinatus fatty infiltration (any) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without (n = 13) | With (n = 26) | Without (n = 33) | With (n = 6) | Without (n = 33) | With (n = 4) | Without (n = 34) | With (n = 5) | Without (n = 20) | With (n = 19) | Without (n = 15) | With (n = 23) | ||

| WORC (%) | 80 (20) | 74 (28) | 76 (25) | 74 (31) | 75 (26) | 87 (20) | 78 (24) | 63 (36) | 75 (23) | 77 (28) | 79 (19) | 74 (29) | |

| Quick-Dash Main | 18 (18) | 18 (19) | 16 (18) | 25 (24) | 19 (19) | 6 (6)* | 16 (17)γ | 27 (30) | 20 (20) | 15 (17) | 14 (15) | 21 (21) | |

| SF-12 | Physical | 46 (12) | 47 (10) | 47 (10) | 44 (11) | 47 (11) | 42 (11) | 48 (10) | 35 (4)* | 48 (9) | 44 (11) | 49 (7) | 45 (12) |

| Mental | 52 (8) | 51 (9) | 52 (8) | 48 (13) | 51 (9) | 60 (4) | 51 (8) | 54 (13) | 51 (8) | 52 (10) | 52 (7) | 50 (10) | |

| Pain score | 1.3 (1) | 2.2 (3) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 2 (2) | |

| Constant score difference | 9 (12) | 6 (11) | 6 (11) | 13 (16) | 7 (12) | 7 (8) | 6 (11) | 15 (11) | 5 (13) | 9 (10) | 8 (2) | 8 (3) | |

| Strength loss (kg) | 3 (5) | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | 4 (7) | 3 (6) | 2 (3) | 2 (4) | 8 (8) | 2 (6) | 3 (4) | 0.3 (2) | 4 (6)* | |

| ROM injured side (°) | Flexion Abduction External rotation | 166 (23) | 166 (19) | 166 (18) | 165 (32) | 167 (19) | 159 (27) | 167 (20) | 159 (23) | 169 (15) | 163 (25) | 166 (17) | 166 (22) |

| 161 (29) | 155 (29) | 155 (29) | 167 (28) | 159 (26) | 154 (35) | 157 (29) | 154 (31) | 158 (28) | 156 (30) | 153 (34) | 160 (26) | ||

| 74 (13) | 73 (14) | 72 (14) | 76 (10) | 76 (9) | 55 (25) | 75 (10) | 57 (23) | 72 (13) | 74 (15) | 75 (12) | 72 (15) | ||

*Values are expressed as the mean (SD). Abbreviations and values are as described for Table 3. p = 0.01. The total number of patients varied from 43 because each tendon could not always be rated in all types of measurement for all patients as a result of the technical limitations of the ultrasound.

Table 5.

The impact of biceps pathology and subacromial impingement on functional outcome measures.

|

|

Biceps pathology (any) |

Biceps tendon subluxation |

Subacromial impingement |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without (n = 12) | With (n = 27) | Without (n = 26) | With (n = 11) | Without (n = 17) | With (n = 22) | ||

| WORC (%) | 79 (21) | 74 (28) | 71 (28) | 85 (16) | 74 (21) | 77 (29) | |

| Quick-Dash Main | 17 (17) | 18 (20) | 20 (20) | 12 (14) | 20 (17) | 16 (20) | |

| SF-12 | Physical | 49 (7) | 45 (12) | 47 (10) | 46 (12) | 44 (11) | 48 (10) |

| Mental | 56 (7) | 50 (9)* | 51 (10) | 52 (6) | 52 (9) | 51 (9) | |

| Pain score | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 2 (3) | |

| Constant score difference | 6 (9) | 8 (13) | 6 (11) | 7 (9) | 10 (8) | 5 (13) | |

| Strength loss (kg) | 1 (3) | 3 (6) | 3 (6) | 2 (5) | 3 (4) | 2 (6) | |

| ROM injured side (°) | Flexion Abduction External rotation | 166 (18) | 166 (21) | 167 (17) | 166 (19) | 164 (18) | 167 (22) |

| 151 (32) | 160 (27) | 157 (27) | 159 (31) | 147 (31) | 164 (25) | ||

| 78 (13) | 71 (13) | 75 (12) | 69 (17) | 71 (17) | 75 (11) | ||

*Values are expressed as the mean (SD). Abbreviations and values are as described for Table 3. p < 0.05.

Discussion

The present study describes the prevalence of soft-tissue injury following GT fractures, as well as their functional impact at an average follow-up of 2.4 years. It is likely that some of the pathologies found on ultrasound were present pre-injury because Girish et al. found an incidence of up to 10% full supraspinatus tears in asymptomatic men aged 40 years to 70 years.26 It has also been suggested that rotator cuff tears represent a normal degenerative process (increased incidence with increasing age).27 However, whether it was pre-existing or caused by the fracture, the present study described the negative functional impact of rotator cuff pathology on patients recovering from isolated GT fractures.

Loss of abduction strength in asymptomatic patients with rotator cuff tears has been described previously.28 In the present study, patients lost an average of 3 kg of abduction strength with respect to their unaffected limb in the presence of supraspinatus muscle atrophy, with or without a concomitant tear. This atrophy was also associated with greater residual GT displacement (7.3 mm versus 0.7 mm, p = 0.001), which suggests that atrophy of the rotator cuff may occur following shortening of the effective muscle length of the rotator cuff in the absence of tendon tear. This has never before been described in the rotator cuff following GT fractures and may help explain, in part, the poor outcomes historically associated with displaced GT fractures.

Indeed, tears of any muscle of the rotator cuff and supraspinatus fatty atrophy were associated with a poorer functional outcome in this study. As already noted, these abnormalities may have occurred pre-injury, during the trauma, or over time as a result of the altered mechanics and/or subacromial impingement. The functional impact of this rotator cuff tear and/or supraspinatus fatty atrophy, however, may warrant advanced imaging (such as ultrasound or MRI) and consideration of further treatment in the patient evolving poorly following a GT fracture.

Biceps abnormalities were present in 27 patients and included partial or full-thickness tears and tendon subluxation. The presence of biceps pathology was associated with a statistically significant lower SF-12 Mental score (50 with pathology versus 56 without pathology; p < 0.05), although this may not be clinically significant.

Another element that was clearly associated with functional outcome in patients following GT fracture was the financial salary compensation or insurance received during the convalescent period. Patients who received worker’s compensation performed significantly worse on WORC, SF-12 v2, Constant and abduction amplitude than patients with private insurance. In the case of worker’s compensation, this negative relationship is considered to be the result of a higher rate of noncompliance and secondary gain in this population, and is consistent with outcomes following other injuries to the shoulder.19,29,30

A major weakness of the present study is the 46.2% rate of participation among candidates meeting the inclusion criteria. This was likely a result of the time commitment required (two appointments; one for the orthopaedic clinic and one for the shoulder ultrasound), which was unacceptable for many patients. However, we pulled the charts and radiographs on the nonparticipants, and determined that the group of patients who accepted to participate and the group of those who refused were radiologically and demographically comparable.

In conclusion, our assessment of the incidence of rotator cuff and biceps pathology in isolated GT fractures showed that they are common and can have a significant functional impact. Rotator cuff tears and supraspinatus atrophy may occur following GT fractures and are associated with a poorer outcome. Advanced imaging (ultrasound or MRI) may be helpful to evaluate the poorly evolving patient with a GT fracture because soft tissue pathology could be the cause and may be amenable to surgical treatment.

Acknowledgements

This work was part of a scientific presentation at the Orthopaedic and Trauma association in October 2012.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The institution of one or more of the authors has received funding from: Arthrex, Conmed, Depuy, Smith and Nephew, Linvatec, Synthes, Stryker, Zimmer and Tornier. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical Review and Patient Consent

Research Ethics committee approval was granted by the HSCM: CER 211-638.

References

- 1.Warner J, Costouros J, Gerber C. Fractures of the proximal humerus. In: Bucholz RW, Heckman JD, Court-Brown C, eds. Rockwood & Green’s fractures in adults. Sixth edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2006:1162–209.

- 2.Gruson KI, Ruchelsman DE, Tejwani NC. Isolated tuberosity fractures of the proximal humerus: current concepts. Injury 2008; 39: 284–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bono CM, Renard R, Levine RG, et al. Effect of displacement of fractures of the greater tuberosity on the mechanics of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg 2001; 83B: 1056–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.George MS. Fractures of the greater tuberosity of the humerus. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2007; 15: 607–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green A, Izzi J., Jr Isolated fractures of the greater tuberosity of the proximal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2003; 12: 641–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawkins RJ, Angelo RL. Displaced proximal humeral fractures. Selecting treatment, avoiding pitfalls. Orthop Clin North Am 1987; 18: 421–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park TS, Choi IY, Kim YH, et al. A new suggestion for the treatment of minimally displaced fractures of the greater tuberosity of the proximal humerus. Bull Hosp Jt Dis 1997; 56: 171–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Platzer P, Kutscha-Lissberg F, Lehr S, et al. The influence of displacement on shoulder function in patients with minimally displaced fractures of the greater tuberosity. Injury 2005; 36: 1185–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bahrs C, Rolauffs B, Dietz K, et al. Clinical and radiological evaluation of minimally displaced proximal humeral fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2010; 130: 673–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallo RA, Sciulli R, Daffner RH, et al. Defining the relationship between rotator cuff injury and proximal humerus fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2007; 458: 70–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moosmayer S, Tariq R, Stiris MG, et al. MRI of symptomatic and asymptomatic full-thickness rotator cuff tears. A comparison of findings in 100 subjects. Acta Orthop 2010; 81: 361–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirkley A, Alvarez C, Griffin S. The development and evaluation of a disease-specific quality-of-life questionnaire for disorders of the rotator cuff: The Western Ontario Rotator Cuff Index. Clin J Sport Med 2003; 13: 84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996; 34: 220–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hudak PL, Amadio PC, Bombardier C. Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: the DASH (Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand) [corrected]. The Upper Extremity Collaborative Group (UECG). Am J Int Med 1996; 29: 602–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Constant CR, Murley AH. A clinical method of functional assessment of the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1987; 214: 160–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuff DJ, Pupello DR. Prospective evaluation of postoperative compliance and outcomes after rotator cuff repair in patients with and without worker’s compensation claims. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2012; 21: 1728–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Denard PJ, Ladermann A, Burkhart SS. Long-term outcome after arthroscopic repair of type II SLAP lesions: results according to age and workers’ compensation status. Arthroscopy 2012; 28: 451–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neer CS., II Displaced proximal humeral fractures I: classification and evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1970; 52: 1077–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Müller ME, Nazarian S, Koch P, et al. The comprehensive classification of fractures of long bones, First edition New York, NY: Springer, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mutch J, Laflamme GY, Hagemeister N, et al. A new morphological classification for greater tuberosity fractures of the proximal humerus: validation and clinical implications. Bone Joint J 2014; 96B: 646–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lenza M, Buchbinder R, Takwoingi Y, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging, magnetic resonance arthrography and ultrasonography for assessing rotator cuff tears in people with shoulder pain for whom surgery is being considered. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 9: CD009020–CD009020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peetrons P. Ultrasound of muscles. Eur Radiol 2002; 12: 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woodhouse JB, McNally EG. Ultrasound of skeletal muscle injury: an update. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2011; 32: 91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wall LB, Teefey SA, Middleton WD, et al. Diagnostic performance and reliability of ultrasonography for fatty degeneration of the rotator cuff muscles. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94: e83–e83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khoury V, Cardinal E, Brassard P. atrophy and fatty infiltration of the supraspinatus muscle: sonography versus MRI. Am J Roentgenol 2008; 190: 1105–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Girish G, Lobo LG, Jacobson JA, et al. Ultrasound of the shoulder: asymptomatic findings in men. Am J Roentgenol 2011; 197: W713–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tempelhof S, Rupp S, Seil T. Age-related prevalence of rotator cuff tears in asymptomatic shoulders. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1999; 8: 296–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schibany N, Zehetgruber H, Kainberger F, et al. Rotator cuff tears in asymptomatic individuals: a clinical and ultrasonographic screening study. Eur J Radiol 2004; 51: 263–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kemp KA, Sheps DM, Luciak-Corea C, et al. Systematic review of rotator cuff tears in workers’ compensation patients. Occup Med 2011; 61: 556–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pedowitz RA, Yamaguchi K, Ahmad CS, et al. Optimizing the management of rotator cuff problems. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2011; 19: 368–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]