Abstract

Giant bullae often mimic pneumothorax on radiographic appearance. We present the case of a 55-year-old man admitted to a referring hospital with dyspnea, cough, and increasing sputum production; he refused thoracotomy for tension pneumothorax and presented to our hospital for a second opinion. A computed tomography (CT) scan at our hospital revealed a giant bulla, which was managed conservatively as an exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thoracic surgery was consulted but advised against bullectomy. Giant bullae can easily be misdiagnosed as a pneumothorax, but the management of the two conditions is vastly different. Distinguishing between the two may require CT scan. Symptomatic giant bullae are managed surgically. We highlight the etiology, presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of bullous lung disease, especially in comparison to pneumothorax.

CASE DISCUSSION

A 55-year-old man presented to a referring hospital with shortness of breath, cough, and increased sputum production for 3 days without fever or chills. His past medical history was significant for coronary artery disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). He was not on home oxygen, and his baseline New York Heart Association functional class was I. He had smoked for many years and currently smoked half a pack per day. The patient had no occupational exposures or family history of lung disease. His initial chest x-ray suggested a tension pneumothorax, for which he was offered thoracotomy tube placement. However, he declined it and came to our hospital for a second opinion.

On presentation to our hospital, he was not in respiratory distress and was not cyanotic. His heart rate was 104 beats/minute and his blood pressure was 117/82 mm Hg, and he required 3 L/min oxygen via nasal cannula to achieve a peripheral capillary oxygen saturation of 93%. Chest examination revealed diminished breath sounds on the right with faint wheezing at the apex. He had moderate air movement without wheezing or rales on his left lung. Arterial gas analysis was not done. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest demonstrated a giant bulla occupying approximately 90% of the right hemithorax, mildly displacing his upper mediastinum to the left. There was compression atelectasis on the remainder of the right lung as well as advanced emphysema (Figures 1 and 2). His alpha-1-antitrypsin level was 181 mg/dL (normal range, 90–200 mg/dL).

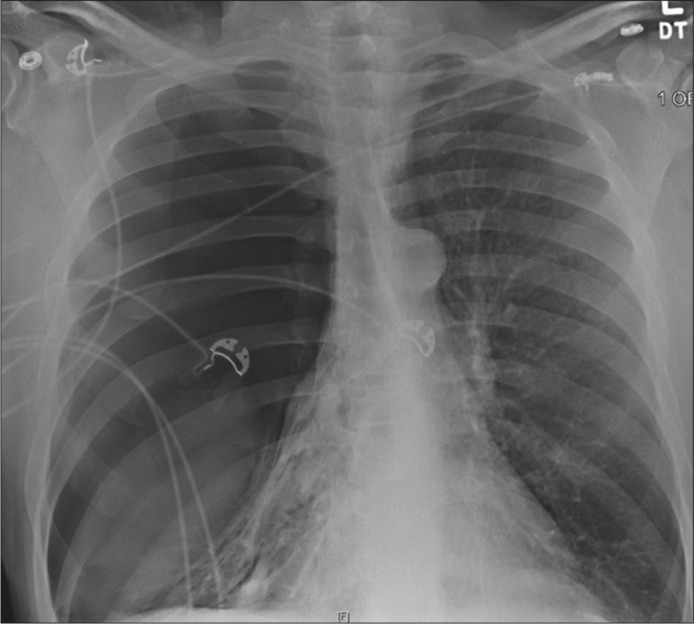

Figure 1.

Chest x-ray showing a large bulla occupying the majority of the right hemithorax.

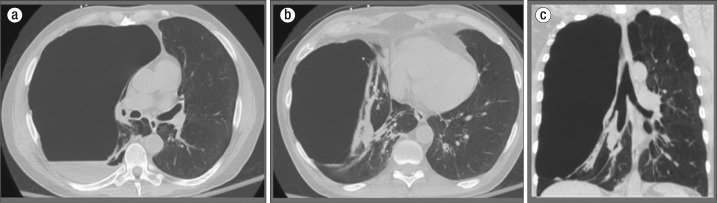

Figure 2.

CT of the chest showing a giant bulla occupying most of the space in the right hemithorax, with (a) mild displacement of the mediastinal structure to the left and (b, c) compressive atelectasis of the right lung and emphysematous change of the left lung.

Thoracic surgery was consulted and recommended against surgical management, as the patient had minimal residual lung and would be at high risk for developing a bronchopulmonary fistula. He was treated for a COPD exacerbation with systemic steroids, antibiotics, and nebulized bronchodilators with symptomatic improvement and was discharged home with oxygen. He was scheduled for pulmonary clinic follow-up at 1 week but was lost to follow up.

DISCUSSION

COPD affects >15 million Americans and is the third leading cause of death, with a mortality rate of 36.4 to 47.6 per 100,000 in the United States (1). COPD is a group of diseases characterized by persistent airflow limitations such as emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and in some cases asthma. Emphysema refers to structural changes associated with COPD, with permanent enlargement of the alveoli and destruction of alveoli walls without overt evidence of fibrosis (2). Most patients with emphysema have moderate to severe airflow obstruction, although some patients have none (3).

Bullous emphysema refers to emphysematous lung with bullae, which are air-filled spaces within the parenchyma that are 1 cm or larger in diameter and consist of a thin wall of visceral pleura with remnants of alveolar and interlobular septa inside (4). Bullae are formed by destruction of interalveolar walls by chronic or less commonly acute stretch injury with increased intraalveolar pressure (5). The natural history of bullous lung disease is usually progressive enlargement as the bullae fill with air and loss of lung function because the irregular, fibrous membranes result in poor gas exchange. If bullae occupy >30% of a hemithorax, they are termed giant bullae. These typically form slowly by gradual filling with air, but rapid enlargement and spontaneous deflation are also possible. As giant bullae occupy spaces in the thorax, they can compress other lung parenchyma and affect gas exchange (4). Distribution of giant bullae is usually unilateral and asymmetric; however, bullous emphysema has bilateral involvement. There are no known factors that determine whether formation is unilateral or bilateral (6).

The major cause of giant bullae formation is cigarette smoking, but they are also associated with intravenous use of methadone, methylphenidate, or talc-containing drugs. Patients with Marfan's syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos type IV, polyangiitis with granulomatosis, Sjogren's syndrome, and sarcoidosis can develop bullae but not typically giant bullae.

Giant bullae can present asymptomatically, with dyspnea, or rarely with hemoptysis (7, 8). Diagnosis is made radiographically by plain chest x-ray demonstrating a bulla occupying more than 30% of a hemithorax. CT scan of the chest is sometimes needed to distinguish giant bullae from a pneumothorax.

In contrast to bullae, a pneumothorax is defined as the presence of air in the pleural space and is classified clinically by whether it developed spontaneously or traumatically. Furthermore, a spontaneous pneumothorax is classified as a primary spontaneous pneumothorax (PSP) if there is no known lung disease or as secondary in the background of chronic lung disease. It is referred to as a tension pneumothorax when associated with varying degrees of hypotension, hypoxia, chest pain, and dyspnea (9).

After bullous lung disease is diagnosed, it is recommended that the team check antitrypsin levels and order pulmonary function tests to guide therapy. Stapled bullectomy, excision, ligation, and endocavitary drainage are different operative techniques to treat bullae or giant bullae (10). Indications for bullectomy include severe dyspnea, pneumothorax, pain, infection, or hemoptysis (11). Contraindications include significant comorbid disease, pulmonary hypertension, and poorly defined bullae. Based primarily on data regarding lung volume reduction surgery (12, 13), relative contraindications for bullectomy include poor forced expiratory volume in 1 second (<30%), hypercapnia, cor pulmonale, and severe hypoxemia.

A few longitudinal studies have reported on outcomes with surgical management. Cooper et al (14) followed patients after resection of giant emphysematous bullae and found significant improvements in pulmonary function, lung volume, and 6-minute walk distance, but most of these improvements began diminishing at 3-year follow-up. Giuntini et al (15) completed a 5-year follow-up of patients who underwent surgery for giant emphysematous bullae and also found improvement in pulmonary function, lung volume, and dyspnea score. They also noted increasing improvement for the first few years with a tapering of this effect beginning around 3 years. Both found surgical management to be fairly safe with low operative mortality, and most postoperative complications involved prolonged air leak (10).

Although surgery is the preferred approach for dealing with symptomatic giant bullae, one case report discussed treating a giant emphysematous bulla with bronchoscopic placement of one-way endobronchial valves (16). These valves are currently being investigated as a way to perform lung volume reduction without an operation in select emphysema patients.

References

- 1.Hoyert DL, Xu JQ. Deaths: preliminary data for 2011. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012;61(6):1–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rennard SI. COPD: overview of definitions, epidemiology, and factors influencing its development. Chest. 1998;113(4 Suppl):235S–241S. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.4_supplement.235s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDonough JE, Yuan R, Suzuki M, Seyednejad N, Elliott WM, Sanchez PG, Wright AC, Gefter WB, Litzky L, Coxson HO, Paré PD, Sin DD, Pierce RA, Woods JC, McWilliams AM, Mayo JR, Lam SC, Cooper JD, Hogg JC. Small-airway obstruction and emphysema in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(17):1567–1575. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deslauriers J, Leblanc P. Management of bullous disease. Chest Surg Clin North Am. 1994;4(3):539–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klingman RR, Angelillo VA, DeMeester TR. Cystic and bullous lung disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 1991;52(3):576–580. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(91)90939-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma N, Justaniah AM, Kanne JP, Gurney JW, Mohammed TH. Vanishing lung syndrome (giant bullous emphysema): CT findings in 7 patients and a literature review. J Thorac Imaging. 2009;24(3):227–230. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e31819b9f2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyers BF, Patterson GA. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 10: Bullectomy, lung volume reduction surgery, and transplantation for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2003;58(7):634–638. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.7.634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagashima O, Suzuki Y, Iwase A, Takahashi K. Acute hemorrhage in a giant bulla. Intern Med. 2012;51(18):2673. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.8335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noppen M, De Keukeleire T. Pneumothorax. Respiration. 2008;76(2):121–127. doi: 10.1159/000135932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Berkel V, Kuo E, Meyers BF. Pneumothorax, bullous disease and emphysema. Surg Clin North Am. 2010;90(5):935–953. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehran RJ, Deslauriers J. Indications for surgery and patient work-up for bullectomy. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 1995;5(4):717–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fishman A, Martinez F, Naunheim K, Piantadosi S, Wise R, Ries A, Winmann G, Wood DE. National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research Group A randomized trial comparing lung-volume-reduction surgery with medical therapy for severe emphysema. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(21):2059–2073. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinez FJ, Chang A. Surgical therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;26(2):167–191. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-869537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schipper PH, Meyers BF, Battafarano RJ, Guthrie TJ, Patterson GA, Cooper JD. Outcomes after resection of giant emphysematous bullae. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78(3):976–982. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palla A, Desideri M, Rossi G, Bardi G, Mazzantini D, Mussi A, Giuntini C. Elective surgery for giant bullous emphysema: a 5-year clinical and functional follow-up. Chest. 2005;128(4):2043–2050. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noppen M, Tellings J, Dekeukeleire T, Dieriks B, Hanon S, D'Haese J, Meysman M, Vincken W. Successful treatment of a giant emphysematous bulla by bronchoscopic placement of endobronchial valves. Chest. 2006;130(5):1563–1565. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.5.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]