Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells have revolutionized the field of cancer immunotherapy. Genetically redirected killer CD19-CAR T cells have achieved lasting therapeutic effects in patients with B-cell leukemias.1,2 In a brilliant new twist on this system, Ellebrecht et al., as recently reported in Science,3 have conceived of chimeric autoantigen receptor (CAAR) T cells to specifically eliminate autoreactive B cells. Their strategy is reminiscent of that of angler fish. In the dark depths of the sea, the angler fish has developed a clever way to lure its prey by dangling a luminous appendix in front of its powerful mouth. Any unfortunate fish trying to eat this bait is quickly eaten in return. For their part, CAAR T cells lure and kill autoreactive B cells by baiting them with their autoantigen. The CAAR T-cell strategy was used to eliminate desmoglein 3 (Dsg3)-specific autoreactive B cells responsible for the blistering autoimmune disease pemphigus vulgaris (PV) (Figure 1). The approach was found to be specific and efficient in animal models of PV. Although ultimate proof of concept awaits testing in humans, this new approach opens up vast perspectives for T cell–mediated immunotherapy of B-cell autoimmune diseases and possibly beyond.

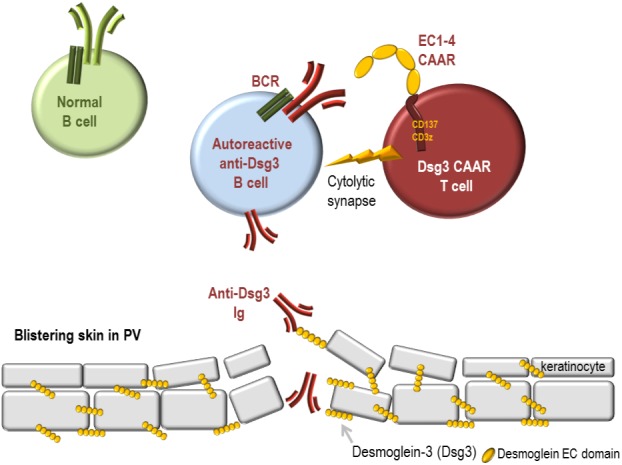

Figure 1.

How desmoglein 3–chimeric autoantigen receptor (Dsg3-CAAR) T cells lure and specifically eliminate autoreactive anti-Dsg3 B cells responsible for skin blistering in pemphigus vulgaris (PV) while sparing normal B cells. PV is a severe autoimmune disease caused by pathogenic autoreactive B cells expressing B-cell receptors (BCR) with immunoglobulins (Ig) specific for desmoglein-3 (Dsg3). These autoantibodies perturb the adhesion of keratinocytes and cause skin blistering. Dsg3-autoreactive B cells can be lured to their own demise when they engage their BCR onto genetically engineered T cells expressing a Dsg3-CAAR (Dsg3-CAAR T cells). The BCR recognizes the ectodomain of the CAAR, exposing four cadherin domains of Dsg3 as epitopes. This extracellular portion of the CAAR is linked to a CD137/CD3zeta chain that permits intracellular signaling and cytolytic activation of the T cell. A synapse forms between the Dsg3-CAAR T cell and Dsg3-specific B cells, cytokines are produced, and B-cell lysis occurs. By contrast, B cells with other BCRs (green) are not recognized and are not killed by Dsg3-CAAR T cells.

The technology used to produce Dsg3-CAAR T cells is based on second-generation CD19-CAR T-cell constructs tested in the most recent B-cell leukemia trials. A lentiviral vector was used to express in T cells a chimeric transmembrane protein comprising an intracellular CD137/CD3zeta signaling chain linked to a dimerization-competent CD8a transmembrane domain fused to an ectodomain. In contrast to conventional CARs, which display single-chain immunoglobulin (Ig) fragments to recognize their targets, the ectodomain of Dsg3-CAAR displays conformational epitopes of the Dsg3 antigen. These epitopes are specifically recognized by pathogenic autoreactive B cells in PV. Much like the angler fish appendix, this extracellular portion of the CAAR must be of optimal length to function as effective bait so as to permit a productive “bite” by the killer T cell. Ellebrecht et al. tested different lengths for the extracellular portion of the Dsg3-CAAR, aiming to include as many B-cell epitopes as possible without rendering it so long as to compromise T-cell activation, which depends on the intermembrane distance of the immunologic synapse. The first four extracellular cadherin domains of Dsg3 (EC1–4) recognized by all PV sera worked well as an ectodomain and allowed the formation of an effective synapse as well as a specific and strong cytolytic activity against anti-Dsg3 B-cell hybridomas in vitro.

Importantly this EC1–4 CAAR could function even in the presence of secreted anti-Dsg3 antibodies found in PV patients. These secreted autoantibodies can also bind to the CAAR and mediate complex effects. Depending on their affinity, they can either reduce CAAR T-cell activation (but without preventing a cytolytic effect) or promote CAAR-T efficacy and persistence due to receptor-mediated costimulation. A preclinical proof of efficacy of Dsg3 CAAR T cells was shown in an in vivo murine model of PV in which immunodeficient NSG mice were injected with a polyclonal mixture of anti-Dsg3 hybridomas and CAAR T cells.3 In this short-term model, Dsg3 CAAR T cells specifically and efficiently controlled the growth of hybridomas even in the presence of soluble Ig, reduced serum autoantibody titers, and prevented Ig deposit in the mucosa and the formation of mucosal blisters. When CD19+ anti-Dsg3 hybridomas were implanted in mice, Dsg3 CAAR T cells were found to be as efficient as CD19 CAR T cells at eliminating target B cells in vivo.

The specificity of the approach and lack of off-target effects were verified in particular with keratinocytes, which express the physiological ligands of Dsg3 desmocollins and desmogleins found in cell-to-cell adhesion desmosomes of the skin. Dsg3-CAAR T cells did not kill human keratinocytes; nor did they infiltrate the skin of human skin-grafted immunodeficient mice in vivo or exhibit off-target effects on murine skin, which bears functional moieties similar to that of human skin. Keratinocytes were not resistant to T-cell killing because as positive controls, PX44 CAR T cells specific for Dsg3-1 killed keratinocytes efficiently and infiltrated skin when administered in vivo. Presumably, Dsg3-CAAR T cells are unable to be activated by keratinocyte proteins because their EC1-4 ectodomain may have insufficient affinity for the natural ligands of Dsg3 in these cells, or perhaps cannot reach the ligands of Dsg3 in the skin. Thus, only B cells bearing Ig specific for Dsg3 seem to have sufficient affinity to activate Dsg3-CAAR T cells to kill.

Taking these findings together, the Dsg3-CAAR T cell strategy reported by Ellenbrecht et al. has strong potential to become a new therapy for PV despite some potential caveats. PV patients are currently treated via anti-CD20 antibody depletion. This indiscriminate removal of B cells places patients at risk of infection and provides a benefit that is often temporary as patients relapse owing to outgrowth of CD20-negative autoantibody–secreting plasmablasts. By contrast, CAAR T cells could induce long-lasting remission by eliminating pathogenic Dsg3-reactive sIg+ memory B cells as well as Dsg3-reactive CD20 negative sIg+ short-lived plasmablasts, while preserving other B cells and patient immunity. However, several key issues should be examined. Trials with adoptive T-cell transfer or CAR T cells in cancer applications have revealed issues including biodistribution problems, variable composition of the T-cell product, lack of cell persistence, and target-cell escape and toxicity.4 It is not yet known what phenotype of CAAR T cell will be obtained in PV, what dose will be required, or whether the CAAR T cells will be able to reach all target B cells in the skin, secondary lymphoid organs, and bone marrow. Ellebrecht et al. have only tested CAAR T cells in vivo against hybridoma cells introduced into NSG mice. These hybridoma cells are unlikely to be distributed in a manner identical to that of a patient's autoreactive B cells.

Compared with cancer, the use of genetically engineered T cells in autoimmune diseases has advantages and inconveniences. Mechanisms of escape from CAAR T cells—which is predicted to occur based on preclinical results and as occurs with any molecular-targeted therapy, including CD19 CAR T cells1—should have lesser consequences in autoimmune diseases than in cancer. Surviving autoimmune B cells are unlikely to mutate or expand, and the unaffected sIg-negative B cells should not compromise therapeutic efficacy because they do not contribute to autoantibody production. A sustained effect of CAAR T cells may be needed to remove all target cells, including those that escape. Presumably, this should be easier in an autoimmune disease than in cancer owing to the smaller number of target cells present in the patient. Dsg3-CAAR T cells can persist for at least 3 weeks in NSG mice, but it is not clear how long they will persist in patients. Adoptive T-cell therapy shows that most cells rapidly disappear from the circulation. Perhaps the persistence of CAAR T cells will be triggered by low-affinity anti-Dsg3 soluble antibodies, which will prevent their exhaustion through anti-CD137 stimulation. If this occurs, this could represent an advantage of CAAR T cells.

An important concern with the use of CAAR T cells in autoimmune diseases is toxicity. Indeed, the risk–benefit situation is not as favorable in autoimmune diseases that are generally manageable as it generally is in the case of refractory cancer. Major toxicities have occurred in patients treated with CD19-CAR T cells, although most are well managed. These have included cytokine-release syndrome and macrophage-activation syndrome, as well as off-target tissue toxicity, including neurological toxicity.1 Ellebrecht et al. verified that Dsg3-CAAR T cells do not kill phagocytes that can take up anti-Dsg3 antibodies via their Fc receptor. Dsg3-CAAR T cells also failed to kill keratinocytes. However, the situation may be very different in PV patient in whom the pathology causes the skin to be damaged and inflamed. If CAAR T cells are administered, their effects could be modified by inflammatory signal loops and by the contribution of innate immune factors such as human complement. Thus, as a safety feature, the CAAR T cells should probably be equipped with an inducible suicide gene function. The safety of the procedure will most likely need to be better ascertained in future studies, but only clinical trials in humans will show whether the CAAR T-cell approach is feasible, safe, and efficient.

CAAR T cells represent a new addition to the list of genetically engineered cells for immunotherapy, which includes CAR T cells equipped with Ig or DARpins (designed ankyrin repeat proteins), T-cell receptor–modified T cells, and, more recently, CAR natural killer cells.4 However, this is the first time that engineered T cells have been used in autoimmune diseases. Ultimately, CAAR might find application against B-cell autoimmune diseases other than PV, provided that the autoantigens are well defined, can be efficiently displayed on T cells, and do not interfere with physiological functions. However, relatively few autoantigens have been identified,5 and not all autoantigens may be amenable to display. While additional work is certainly needed, this approach might also be used to eliminate allograft-reactive B cells in organ transplantation, as well as pathogenic B cells induced in patients who become immunized against therapeutic proteins. One limitation could be the time and cost of manufacture of this cell and gene therapy product if prepared in an autologous setting. Further advances in genetic engineering may bring us off-the-shelf universal CAAR T cells in the near future. Let's bet that these new perspectives will create even more excitement in the field of immunotherapy than CAR T cells have already generated.

References

- Tasian, SK and Gardner, RA (2015). CD19-redirected chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells: a promising immunotherapy for children and adults with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Ther Adv Hematol 6: 228–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruella, M and June, CH (2016). Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for B cell neoplasms: choose the right CAR for you. Curr Hematol Malig Rep; e-pub ahead of print 30 July 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ellebrecht, CT, Bhoj, V, Nace, A, Choi, EJ, Mao, X, Cho, MJ et al. (2016). Reengineering chimeric antigen receptor T cells for targeted therapy of autoimmune disease. Science 353: 179–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, MC and Riddell, SR (2015). Designing chimeric antigen receptors to effectively and safely target tumors. Curr Opin Immunol 33: 9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sette, A, Paul, S, Vaughan, K and Peters, B (2015). The use of the immune epitope database to study autoimmune epitope data related to alopecia areata. J Investig Dermatol 17: 36–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]